Eric Zweig's Blog, page 22

March 23, 2016

Art Ross’s Broken Record

Tomorrow night (March 24, 2016) the Boston Bruins will hold a short ceremony to honour Claude Julien for passing Art Ross as the winningest coach in team history. Ross held the Bruins coaching record for nearly 92 years, from the time the team won its first game on November 1, 1924, until Julien equalled him with his 387th Boston victory on March 3, 2016 and surpassed him with win #388 two games later on March 7.

Tracking coaching victories – especially in the early days – is not as easy as you may think. Historically, NHL game sheets have never listed the name of the man behind the bench, so the fact that old-time writers used the words coach and manager interchangeably (regardless of whether they meant what we’d think of today as the coach, assistant coach, or general manager) makes it difficult to know for certain who was ever really running the team. This was all made abundantly clear to me when Dan Diamond & Associates produced the first edition of Total Hockey in 1998 and among my many jobs (which is one I continue to do for the annual NHL Official Guide & Record Book) was to build and maintain the coaching database.

Art Ross with the 1930-31 Bruins. (Boston Public Library 05_02_010561).

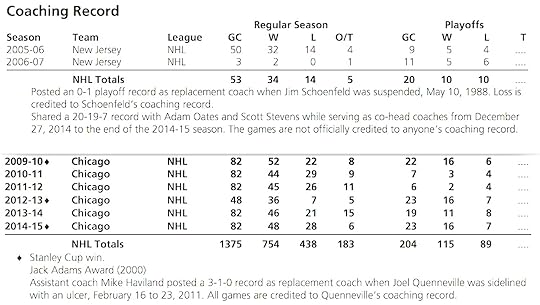

Longtime NHL Statistician and Information Officer Benny Ercolani has established some guidelines for coaching wins and losses. The basic rule is that whoever is hired to be the coach is credited with the decision on any given night whether he is actually behind the bench or not. For example, when Punch Imlach was famously hospitalized during the 1966-67 season and King Clancy led the team to a 7-1-2 record in his absence, those 10 games are all credited to Imlach. (We include a note in our coaching database to explain these situations – when we are aware of them!) You can see more recent examples of this in the 2016 NHL Guide by checking Joel Quenneville’s record on page 40, or Lou Lamoriello’s on page 122. (A similar note will be added to John Tortorella this summer explaining the three games he missed in Columbus after breaking a rib in a practice in January.)

Segments of the coaching records for Lou Lamoriello (above) and Joel Quenneville.

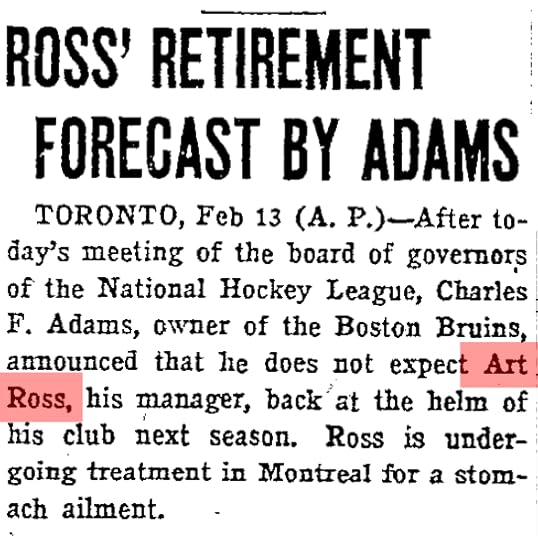

Over his years in Boston, there were many occasions when Art Ross was credited with a win, loss, or tie despite being absent from games. From late January to early March of 1928, Ross was sidelined by a stomach ailment so serious it was thought he might be forced to retire. Defenceman Sprague Cleghorn (who was also serving as an assistant coach that season) took over as coach for nine games and posted a record of 6-1-2. Ross would later miss games for health reasons in 1932-33 and 1933-34 and would also turn over coaching duties to Dit Clapper – sometimes for weeks at a time – while on scouting trips to scrounge players in his role as general manager during the years of World War II. Still, all those missing games are included in Ross’s overall Bruins record, which stands at 387-290-95 for his 17 seasons behind the bench during a time when schedules ranged from 30 to 50 games.

Article from the Boston Globe, February 14, 1928.

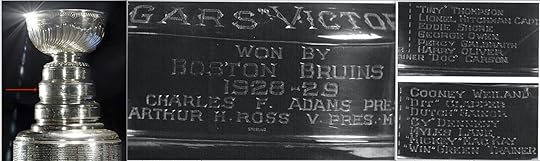

Even so, perhaps the quirkiest aspect of Art Ross’s coaching tenure in Boston is the fact that he just recently had an entire lost season returned to his record. The problem dates back to 1958 when the Stanley Cup was remodelled to standardize the size of the haphazard bands on the “barrel” of the trophy used since the late 1920s.

Duplicate of the original Boston Bruins band from 1929.

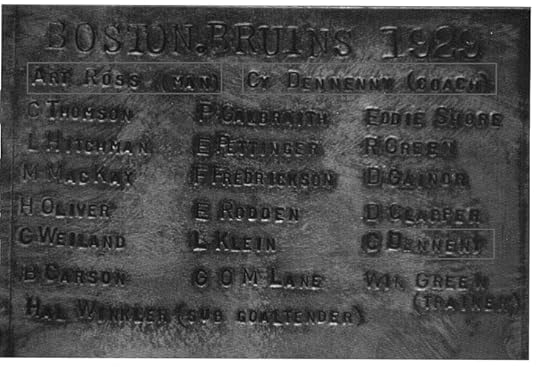

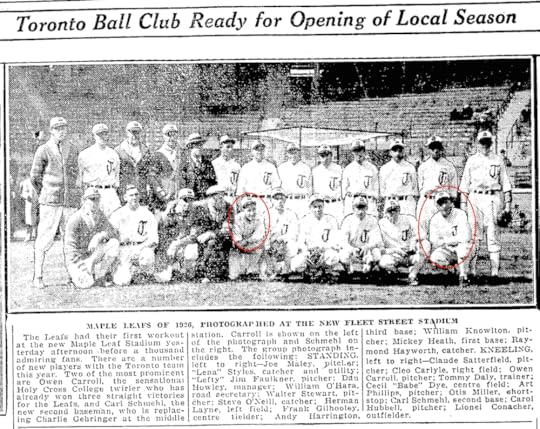

On the original band the Bruins engraved to commemorate their first Stanley Cup victory in 1929 (and which still appears on the the “neck” of the Cup today), Art Ross was noted as Vice President and Manager. No one is designated as the coach. When the 1929 Bruins were added to the first standard-sized band atop the barrel in 1958, Ross was designated Manager, but this time Cy Denneny’s name appeared twice; once with his fellow players and once as the team’s coach. Some time afterwards, Ross’s coaching line for 1928-29 was deleted and Denneny was credited with the Bruins’ record of 26-13-5. The decision appears to have been based mainly on the Stanley Cup engraving.

Boston’s 1929 victory displayed on the new band created in 1958.

On June 10, 2013, I received a phone call from Benny Ercolani. With Boston facing Chicago for the Stanley Cup and the possibility the Bruins might win it again after their 2011 victory over Vancouver, the Elias Sports Bureau was investigating whether Claude Julien would become the first Boston coach to win the Stanley Cup twice or if Art Ross should be credited with the Bruins victories in 1928-29 and 1938-39. (He would also win it again as VP and GM in 1940-41 when Cooney Weiland was the coach.)

Art Ross drinks from the Stanley Cup in 1939. (Photo courtesy of Art Ross III.)

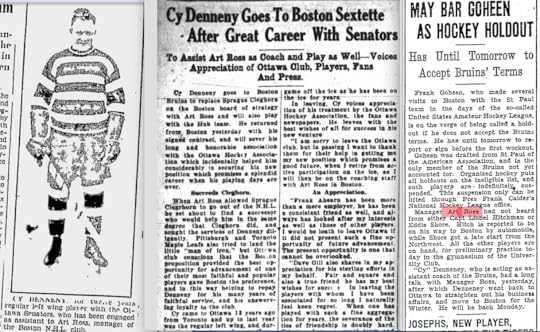

Elias had found no evidence that Denneny coached the Bruins in 1928-29, so Benny asked me to investigate. I pored over as many period newspapers as I could, and while some do note Denneny as coach (as they had for assistant coach Sprague Cleghorn the year before), the vast majority indicated that he’d been signed to play for the Bruins and to assist Art Ross in his duties as coach and manager. Bruins programs from the 1928-29 season clearly list Denneny as “left wing and assistant coach.” Newspapers in Boston and Ottawa (where Denneny had starred for years) are pretty clear too – and when Ross did turn over coaching duties to Frank Patrick in 1934, all stories about it state that Ross has been the coach in Boston since the team’s beginning in 1924.

Articles from the Ottawa Citizen, the Ottawa Journal

and the Boston Globe,October 25 and 26, 1928.

And so, beginning in 2013-14, Art Ross had the 1928-29 season returned to his coaching record, giving him the 387-win total that now ranks second in Bruins history behind Claude Julien.

Write-up on Cy Denneny that appeared in Bruins programs during 1928-29.

March 16, 2016

Howe About That?

On Monday of this week, the hockey world noted the 54th anniversary of Gordie Howe scoring his 500th career goal. On March 14, 1962, Howe joined Maurice Richard as the only players in NHL history to have then reached this milestone. Richard had retired in 1960 with 544 career goals.

A few weeks earlier, in the January 27, 1962, edition of the Canadian national Weekend Magazine, Andy O’Brien examined the NHL players of the day to determine who might surpass Richard’s record. While noting a couple that might come close, O’Brien believed only Gordie Howe had a chance.

O’Brien did not look very far into the future; ignoring both Frank Mahovlich (who’d scored 48 goals in 1960-61 and would end the 1961-62 season with 142 for his career en route to a total of 533) and Bobby Hull (who was in the midst of a 50-goal season to bring his career total 151).

Focusing only on the top nine active scorers at the time, O’Brien extended their career scoring averages out to the age of 38, because that was how old Richard had been at his retirement and “I can’t imagine any all-out star going beyond it.”

Here are the final NHL totals (and ages at retirement) of the players O’Brien projected:

Gordie Howe (51) — 801

Bernie Geoffrion (36) — 393

Jean Beliveau (39) — 507

Dickie Moore (37) — 261

Andy Bathgate (38) — 349

Red Kelly (39) — 281

Alex Delvecchio (41) — 456

Vic Stasiuk (33) — 183

Don McKenney (33) — 237

Only Howe (who had 649 goals through 1966-67 when he was 38), Red Kelly and Alex Delvecchio managed to exceed O’Briens’ projections, and of the 135 skaters active in the NHL during the 1961-62 season, he missed out on only Bobby Hull and John Bucyk (who had just 111 goals by the end of that year) as two who would also surpass Richard one day. Of all the others who’ve flown by the Rocket, only Phil Esposito began his career before NHL expansion – and even he was two years away from making his debut at the time of the article.

March 11, 2016

Gut-Check Time…

My recent adventure (as some of you know) began on Friday night, February 26, with an apparently simple case of minor stomach flu. Over the weekend, things got worse. By 7:30 on Monday evening (Feb. 29), Barbara and I made our second trip to the emergency room. This time, a small obstruction was found in my lower abdomen and I was admitted to hospital. Further tests on Tuesday pinpointed a tangle in my small intestine. When the one possible “non-invasive” technique changed nothing, I was rushed into surgery around 11:00 am on Wednesday morning, March 2. Warned of several dire possibilities, when I awoke in the recovery room at exactly 12 noon, I knew it had gone as well as it possibly could. Even so, there were eight more days in hospital before I finally arrived home yesterday (March 10) at noon.

The usual causes for an abdominal obstruction are tumors, scars from prior surgery, or a lingering stomach injury. I have none of those. So, what happened is a mystery. But the take-away, for both Barbara and me, is that if something feels wrong, get it checked out! Untreated (and we were supposed to go away on a small vacation the day we went to the hospital instead), this could have killed me. I am tremendously grateful for the wonderful work of the doctors, nurses, and support staff of the hospital here in Owen Sound.

Weak as a kitten, and very tired, I’ll mostly be taking it easy for the next little while. So stories might appear a little less frequently, or be a lot more “show” and a little less “tell” for a couple of weeks. Still, like Maurice Richard recovered from his charley horse in 1951, I’m back in the saddle again!

March 2, 2016

Three Old Images…

No story this week. Just a few interesting pictures I came across recently…

February 23, 2016

Baseball’s Maple Leafs (The Sequel)

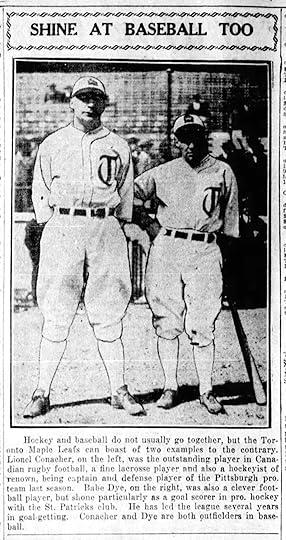

Around these parts, winter has been nothing like the long, tough slog it’s been the past two years. Then again, the forecast is for a big blizzard tomorrow! So, it’s always a good feeling to know that pitchers and catchers have reported to Spring Training. It means summer can’t be too far away. Last January, I posted a story called Hockey Stars Join Baseball’s Maple Leafs. Today’s post continues the story of Babe Dye and Lionel Conacher.

Seasons started later in 1926 (the Maple Leafs opened on April 14 that year), but spring training was already in the news by this week in February. Even so, Toronto’s baseball team wouldn’t actually get down to business until about March 10. At that point, there was still a week to go in the NHL season. When it wrapped up on March 17, Babe Dye’s Toronto St. Pats had missed the playoffs, but Lionel Conacher’s Pittsburgh Pirates qualified for a semifinal series against the eventual Stanley Cup champion Montreal Maroons.

“Manager [Dan] Howley is none too well pleased that post-season hockey may further delay the reporting of Babe Dye and Lionel Conacher,” reported the Toronto Star on March 22, 1926. “Howley feels that since St. Pats have finished the NHL season that Dye should lose little time joining the Leafs, and Conacher should also come on at once if Pittsburgh is eliminated by Montreal.”

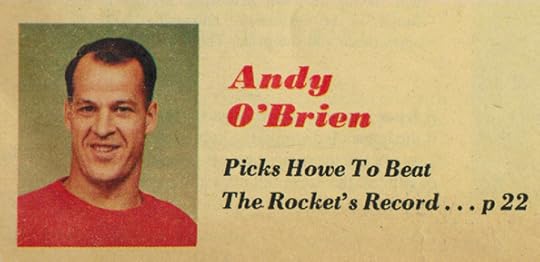

From the Toronto Star on April 28, 1926. Babe Dye is in the red oval near the centre; Lionel Conacher at the right. (Baseball Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell is to Conacher’s left.)

Conacher’s Pirates were eliminated the following day, and the Star noted: “The failure of Babe Dye to report is causing Manager Howley some anxiety. He is expected to join the club the latter part of this week. It is likely that Conacher will accompany his fellow-hockeyist.” The Globe reported that “Babe Dye today wired Manager Howley asking permission to delay his reporting until March 28, as he is not feeling very well. His wish has been granted.”

Dye finally showed up at the Maple Leafs’ Augusta, Georgia, training camp on March 29. Conacher didn’t report until April 6. Dye had only had one hit in 18 at-bats before that day, but suddenly went 5-for-6 with a pair of doubles. Conacher was in uniform the next day, taking batting and fielding practice with the team.

As noted in my story last year, Conacher was a great all-around athlete. He was best known as a lacrosse and football player but had made himself into a fine hockey player too. He’d been a good amateur ballplayer in Toronto, but hadn’t really played the game in three years! Still, “Manager Howley feels confident that the Toronto boy will develop into a good outfielder,” reported the Globe on April 7. Conacher was put into his first game the next day, and recorded his first hit, first run (the game-winner, in fact) and first putout as a professional baseball player in a 9-8 Toronto win over a team from Richmond, Virginia.

This photo appeared in the Winnipeg Tribune on June 14, 1926.

Both Dye and Conacher broke camp with the team, though neither played in the season-opening 8-2 win over Reading on April 14. Dye was a proven minor-league star, and was played up in the publicity to promote Toronto’s home opener at the brand new Maple Leaf Stadium on April 28 … but as also noted in my story last year, neither hockey star contributed much to what would be a championship season for the baseball Maple Leafs in 1926.

With the Blue Jays set to mark their 40th season this year, I for one think it would be cool to seem them wear the 1926 Maple Leafs uniform as a throwback nod to the 90th anniversary of the old ballpark at the foot of Bathurst Street. For some even better photographs of the uniforms, check out this web site.

February 16, 2016

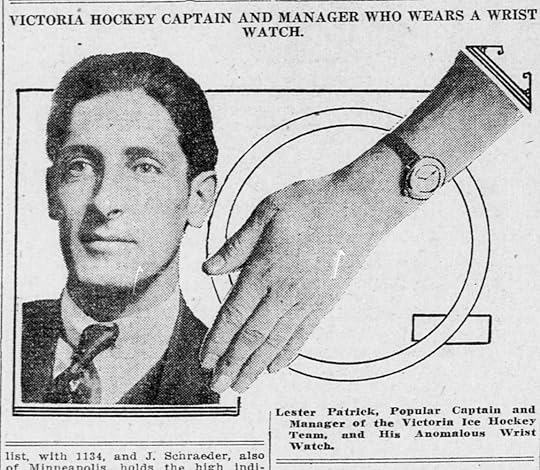

As Wrist Watchy as a Bull Elephant

Since the picture of hockey legend Lester Patrick that appears below originally ran in the Sunday Oregonian newspaper in Portland on February 14, 1915, consider this story a somewhat strange, slightly belated, Valentine’s gift to my wife, Barbara.

You see, it was Lester Patrick who brought us together. (OK, technically, it was publisher Malcolm Lester who brought us together by hiring Barbara to edit my first book, the 1992 novel Hockey Night in the Dominion of Canada. But Lester Patrick was the star of my story, along with his brother Frank, Newsy Lalonde and Cyclone Taylor.)

Barbara’s knowledge of hockey was pretty limited at the time. Raised by two parents from Montreal, it basically consisted of, “Canadiens, good. Maple Leafs, bad.” But Barbara loves history, and historic photographs, and soon she could pick out Lester Patrick in a picture from just about any period of his life.

The fact that Lester is posed with a wrist watch in this picture has nothing directly to do with Barbara and me. But it does fit nicely with our own quirky interests in history and the fact that among the strange bits of trivia we know is that to most people in North America in 1915, a wrist watch – often referred to at the time as a wristlet, or bracelet watch – would have been thought of as – well … girly.

Consider the following excerpt from a story by Christopher Klein that appeared last year on the web site of The History Channel:

Fashionable dandies with portable timepieces on their arms were belittled as “wrist-watch boys” while the tried-and-true pocket watch remained the masculine convention. “The fellow who wears a wrist-watch is frequently suspected of having lace on his lingerie, and of braiding his hair at night,” reported the Albuquerque Journal in May 1914. A New Orleans theater in 1916 assured audiences that the main character in one of its plays was not “portrayed by a wrist-watch, screen actor dude, but by a man’s man.”

“Nobody would ever guess,” said the 1915 story accompanying the wrist watch pic in the Oregonian, “but Lester Patrick, ferocious, wild-acting captain and cover point of the Victoria hockey club of the Coast League, wears the daintiest, most cunning little timepiece imaginable, on his powerful left wrist… Patrick stands about six feet one and weighs 180 pounds and he is about as wrist watchy in action as a bull elephant on a rampage.”

But Lester Patrick was in the vanguard as opinions began to change. Wrist watches had been popular with military leaders in Europe since the 1880s, and by the middle of World War I – even though the United States wouldn’t be in the fighting for almost another year – The New York Times on July 9, 1916, featured a story entitled Changed Status of the Wrist Watch. It reads in part:

“Until recently the bracelet watch has been looked upon by Americans as more or less of a joke. Vaudeville artists and moving-picture actors have utilized it as a funmaker, as a ‘silly ass’ fad. Now, however, since preparedness has become the watchword and timepieces have become a necessary part of the equipment of soldiers, the status of the wrist watch is changing.”

Lester Patrick had received his wrist watch from the citizens of Victoria, B.C. as a thank you for leading its hockey team to a second straight PCHA championship in 1913-14. The Oregonian called it, “Vindication for the wrist watch. Yes sir-e-e-e-e!” So much so that these days, “screen actor dudes” clearly aren’t worried about wearing one.

February 10, 2016

How the Deal Got Done

There are all these talking heads on sports television these days (radio too) telling us the “inside story” on what trades might be in the works. Drives me crazy! Personally, I don’t want people telling me what might happen (but usually doesn’t). I want people giving me analysis when something DOES happen. And, for me, I don’t care who breaks the story. I care about who covers it best.

Admittedly, I don’t exactly have my ear to the ground for these types of things, but for all the talk that he’s been on the block over the past year (and for all those Leaf fans who’ve been wishing they’d trade him for even longer than that), when the nine-player deal that sent Dion Phaneuf to the Senators was announced yesterday, it was amazing to see how fast it got done … and how little had leaked out beforehand.

Dion Phaneuf and Matt Frattin are among the Leafs leaving for Ottawa.

Milan Michalek is one of the Senators headed to Toronto.

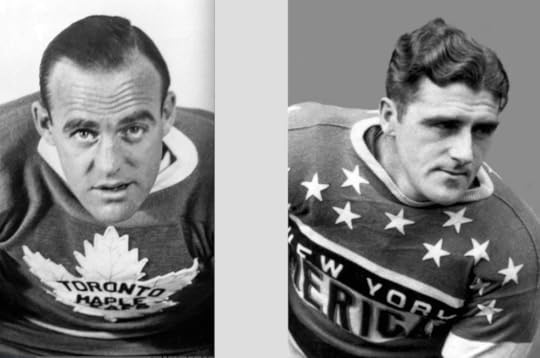

Nine players, and millions of dollars in salary, were swapped between Toronto and Ottawa. Even accounting for inflation, that’s a lot more money than the deal that was considered the biggest in hockey history when the teams from these same cities were last involved in a major blockbuster. And it’s not likely that this deal will have the same immediate impact on the Maple Leafs as the trade to acquire King Clancy on October 10, 1930 (not October 11, as most sources indicate).

The Ottawa Senators had been the top team of the early 1920s, winning the Stanley Cup in 1920, 1921 and 1923 when the NHL had only four teams and still had to compete with other leagues for the top prize. Even after the NHL expanded to 10 teams in 1926-27 and took over control of the Stanley Cup (for all intents and purposes), the Senators won it again that season. But with six of the league’s teams now in the United States, and Toronto and Montreal both much larger than Ottawa, the Canadian capital was the smallest market in the NHL by far. In order to survive, the Senators began selling off their stars; Cy Denneny to Boston, Hooley Smith and George Boucher to the Montreal Maroons, Frank Nighbor to Toronto.

On August 20, 1930, a headline story on the front page of the Ottawa Journal confirmed that the club was willing to entertain offers for King Clancy and that teams had begun making inquiries about the Senators captain and star defenceman.

Over the next few weeks, rumours poured in:

The Maroons were offering $35,000 and right winger Jimmy Ward

Boston was interested, but Ottawa wanted Lionel Hitchman in return

The New York Americans were offering $50,000 in a straight sale

The Rangers were offering $60,000 for Clancy and Hec Kilrea

The Toronto Maple Leafs were silent … until they lost the rights to John Gallagher, a former star junior defenceman Toronto believed they had signed. Trouble was, the Montreal Maroons also believed they’d signed Gallagher, and in late September the NHL sided with them. Writing in the Toronto Star about a month after the Gallagher decision, Charlie Querrie noted:

“Kidding Conny Smythe one day about the result of the Gallagher case and remarking that Montreal generally had the edge in league affairs, the little leader of the Leafs asked me how I would like to see Frank (King) Clancy with the local squad. I looked at him and started to laugh, but when he said he was going east, and remembering ‘Rare Jewel’ [a horse Smythe owned that had recently come in as a long shot and is said to have earned him about $15,000], I began to wonder if he would put it over.”

King Clancy and John Gallagher.

(Photos obtained from the web site of the Society for International Hockey Research.)

Indeed, Conn Smythe left Toronto for Ottawa about October 5, announcing (as The Globe reported on October 7) that he would return with Johnny Gallagher in his possession, “or some better player.” A similar report appeared in the Ottawa Journal that same day under a headline atop the sports page stating: SMYTHE WANTS CLANCY.

A day later, the Globe, the Journal and the Toronto Star (undoubtedly other papers too) announced that Toronto had been given an option on the Ottawa captain. The Star also noted on its front page on October 8 that Smythe had announced the directors of the Toronto Maple Leafs would be asking the fans for their opinion on whether or not King Clancy was worth a price of $35,000 plus two players.

This ad appeared in Toronto’s Globe newspaper on October 9, 1930.

On the evening of Friday, October 10, 1930, the following press release was issued:

The directors of the Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club unanimously resolve to exercise their option on player ‘King’ Clancy with Ottawa. The directorate also appreciate the tremendous enthusiasm and support displayed by the fans of Toronto and all Ontario in this matter.

The Toronto Star reported on some of the many letters the Maple Leafs had received:

“Clancy will be another Rare Jewel…”

“Buy Clancy, don’t let the Maroons get him…”

“See Smythe for Sand, get Clancy if it cost forty grand…”

“If I had $50,000 I would buy the player myself and give him to you…”

“Clancy and the Stanley Cup, some bargain, leave the kid forward line alone, and Day…”

“Oh, Clancy, Clancy, you are the man I fancy, if [Conn] Smythe doesn’t get you, he’ll kick himself in the pantsie…”

The Maple Leafs gave up Art Smith, Eric Pettinger and $35,000 for King Clancy. They made the playoffs in 1930-31 for just the second time in six seasons. A year later, they opened Maple Leaf Gardens and won the Stanley Cup. Soon, with Foster Hewitt broadcasting their games from coast to coast in Canada, the Toronto Maple Leafs were a national institution.

February 4, 2016

Ghost of a Chance

If you’re reading this in Canada, and you’re looking to OD on hockey a day before the Super Bowl, this Saturday, Hockey Day In Canada will be bringing us its annual 13-hours of coverage. This year, the host city is Kamloops, B.C. So here’s an offbeat story from British Columbia’s hockey past.

Before the NHL was formed, the Stanley Cup was a challenge trophy available to the champions of any senior provincial hockey league in Canada. Since all leagues were small and regional, the current Stanley Cup holder would be called upon to defend the Cup (much like a boxing champion or a mixed-martial arts fighter today) against challenges from champions of other leagues . Because the hockey season was so short, these challenges could occur at any time during the winter; before the season, after the season, and even in the middle of the regular season.

The most famous challenger of this early era is the Dawson City team that travelled across Canada – part of the way by dogsled – only to be crushed by Frank McGee and the Ottawa Silver Seven in January of 1905. It was rare for a challenger to defeat the Stanley Cup champion, but teams like the Winnipeg Victorias and the Kenora Thistles did pull it off.

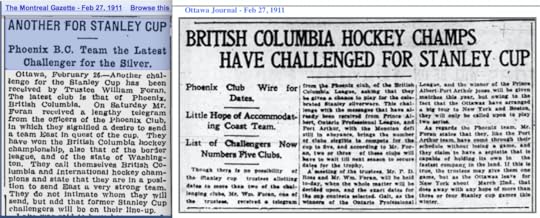

With a population of only 6,000 people in 1907, Kenora will always be the smallest town to win the Stanley Cup. But it wasn’t the only one to take its shot. The smallest of them all was the town of Phoenix, British Columbia (population about 1,000) who challenged for the Stanley Cup in 1911.

Phoenix is located in the south central part of the province, some 300 kilometres from Kamloops and just north of the border with Washington state. The area is known as the Boundary District. Copper was discovered near Phoenix in 1891, and by about 1895 a booming community grew up around the Granby mine. Hockey was introduced to the area a short time later.

The game caught on quickly, and received a big boost in the region in 1907 and 1908 when Frank and Lester Patrick moved to Nelson, B.C., with their father’s lumber business.

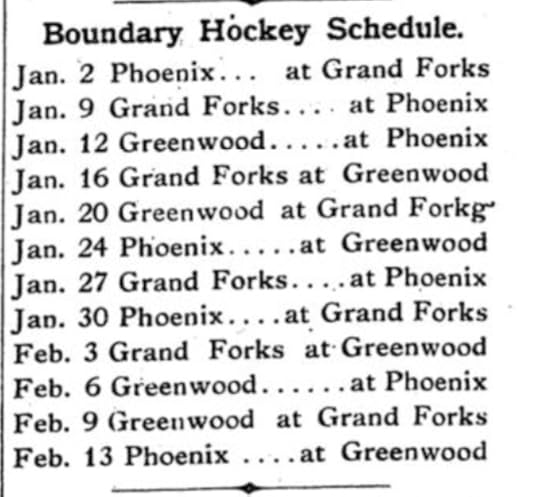

During the winter of 1911, the Boundary League featured teams in Phoenix, Grand Forks, and Greenwood. They played a double-round robin schedule with each team having eight games over the six-week season. Phoenix had imported several new players from all across Canada this year, although none were names fans would recognize today. (You can read the names at the bottom the next clip.)

The season began on January 2 with Phoenix and Grand Forks playing to a 3-3 tie. Phoenix then rattled off five straight wins to clinch the title by January 30. Two more wins followed and Phoenix finished the season on February 13 with a record of 7-0-1. But in order to call themselves provincial champions and have a shot at the Stanley Cup, Phoenix needed to win the tournament at the annual Rossland Winter Carnival.

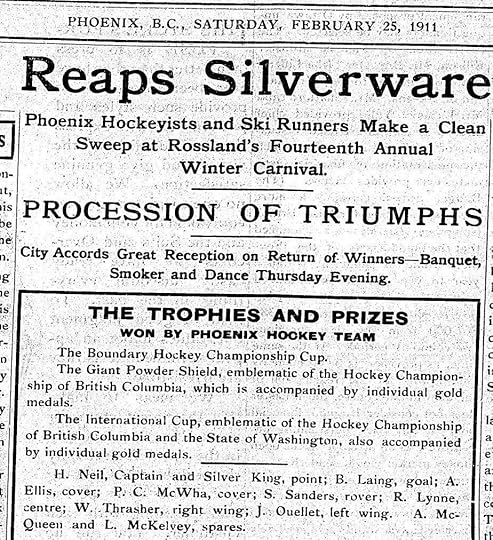

Phoenix claimed the British Columbia title by defeating a beefed-up team from Greenwood and then romping to an 8-2 win over hometown Rossland. They also won the Open challenge series, defeating Rossland once again and crushing the team from Missoula, Montana, 13-5. All four games were played in just five days.

Later, Phoenix beat Rossland one more time, pushing their record for the year to 12 wins and a tie in 13 games. Only one thing marred a nearly perfect season for Phoenix: they never got the chance to test themselves against the Patrick brothers and their powerhouse team in Nelson. Challenges were issued, but Nelson refused to play in the tiny rink in Phoenix, wouldn’t agree to meet the team on neutral ice, and didn’t offer any acceptable dates in their own rink. Nelson even took a pass on the Rossland Carnival.

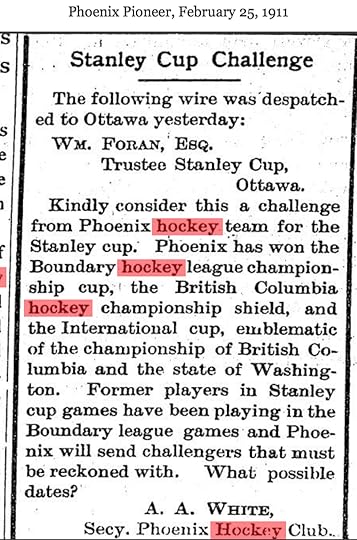

Undaunted, on February 24, 1911, a telegram was sent to William Foran, one of two trustees in charge of administering the Stanley Cup, asking for a series with the Ottawa Senators:

Newspapers across Canada reported on the Phoenix challenge, though few gave the team serious consideration.

When a reply came from William Foran, it was indeed bad news:

“Challenge received. Regret impossible to give you dates this season as there are three other challenges before the trustees. If you so desire will arrange for a series of matches with the holders of the cup at the opening of next season.”

It was strongly hinted that if Phoenix did get a chance to play for the Cup, they would add Frank and Lester Patrick to their lineup. However, as the 1911-12 season approached the brothers were busy creating the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. Phoenix never seems to have followed up with Foran.

The team continued to have success in the Boundary League in the years to come, but there would never again be a Stanley Cup challenge.

In the following years, many men from the tiny town of Phoenix found themselves fighting with the Canadian Army during the first World War. Fifteen sons of Phoenix gave their lives. In a sense, the town did too. The end of the War saw world markets for copper collapse, and in 1919 the Granby mine closed down. The town cleared out, with many former inhabitants leaving everything behind. By 1920, Phoenix was literally a ghost town.

Among the last projects planned in Phoenix was a monument to the local War dead. When many of the town’s buildings were sold for scrap, the $1,200 raised by the sale of iron and lumber from the local hockey rink was put toward the memorial. Today, the Phoenix Cenotaph is the only relic remaining from a once booming town that had hoped to win the Stanley Cup.

January 26, 2016

50 Goals in 50 Games

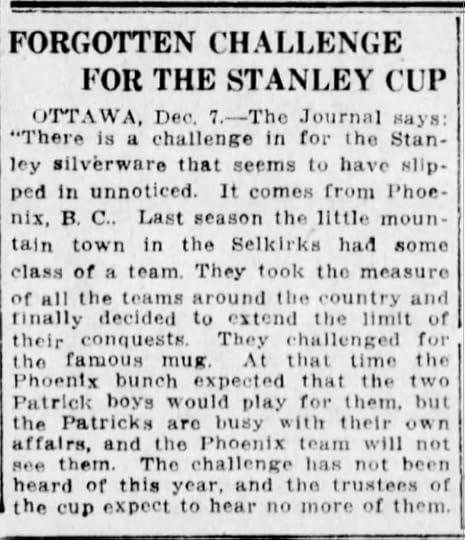

Thirty-five years (and two days) ago, on January 24, 1981, Mike Bossy of the New York Islanders scored his 50th goal of the 1980-81 season. He did it just 50 games. Wayne Gretzky would obliterate this unofficial record with 50 goals in 39 games the next season, but we had no way of knowing this at the time, so it was all pretty exciting!

I was definitely caught up in the race as both Bossy and Charlie Simmer of the Los Angeles Kings took their shot at the 50-50 milestone. Simmer fell just short, with three goals in a 6-4 afternoon victory over Boston that same January day to give him 49 goals in 50 games. Bossy had reached 48 goals through 47 games but was shutout in two straight, and then for two periods that Saturday night against the Quebec Nordiques. He finally scored #49 with 3:10 remaining in the third, and then got #50 with just 1:30 to go. By that time, Hockey Night in Canada had gone live to the game, so I was watching when Bossy scored it. It was quite a moment.

Entering the 1980-81 season, there had been 23 players who’d scored 50 goals in a season since Maurice Richard had first done it in 1944-45. Many, like Bossy, had reached the milestone more than once. But none until that night had managed to match the Rocket’s feat of 50 goals in just 50 games.

Twenty years before Bossy, in the 1960-61 season, Frank Mahovlich, Dickie Moore and Boom Boom Geoffrion were all in the hunt to join Richard as the only 50-goal scorers in NHL history. At the time, there were those who claimed that even if one of them made it (Geoffrion was the only one who did), the record would be tainted because the NHL season was then 70 games long. Richard was not among those who saw it that way.

On January 25, 1961 – with Toronto’s Frank Mahovlich having scored 37 goals in 46 games – Richard spoke about his 50-goal record. “Naturally, I’d rather see someone on the Canadiens do it first,” he said, “but what does it matter? Records are meant to be broken, aren’t they?” When asked about scoring 50 in 70 games versus the 50 he’d played, Richard didn’t see any issue. “The record is for most goals in a season,” he said, “not in so many games. After all, Joe Malone once scored 44 goals in 22 games.”

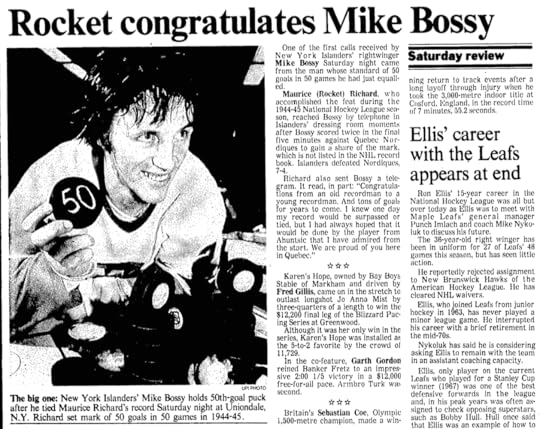

Joe Malone had actually scored his 44 goals while playing in just 20 of 22 scheduled games during the NHL’s inaugural season of 1917-18, but Malone was certainly supportive when the Rocket broke his record in 1944-45. He was at the Forum on February 25, 1945, when Richard netted #45 in his 42nd game and the next day in a bylined article in the Montreal Star, Malone wrote that Richard:

“is one of those players that comes along every once in a while, and I hope he goes on to even greater feats… Ever since he became such a talked-about player I have followed his career with interest… I am happy that my record was broken by such a fine young player. They say he is a fine-living boy, who keeps in tip top shape.”

Richard wasn’t able to be there when Geoffrion became hockey’s second 50-goal scorer on March 16, 1961.

He wasn’t there when Bossy scored 50 in 50 in 1981 either, but he phoned him after the game and sent a telegram of congratulations. Richard was particularly pleased that Bossy was from suburban Montreal. “In fact,” he told reporters later, “I told the Canadiens to draft him in 1977, but they wouldn’t listen to me. They said he wasn’t good enough defensively.”

“What the Canadiens didn’t understand,” Richard added, “is when you can score goals like he can, you don’t watch your man. He watches you.”

Interestingly, Billy Reay said almost the exact same thing about Richard when he left the Canadiens organization to become coach of the Toronto Maple Leafs in the spring of 1957. In discussing his philosophy of letting a player do what he does best, Reay said: “Take Rocket Richard as an example. He’s so tremendous at carrying the puck in and scoring goals that no one ever worries about his defensive ability. Generally, the man covering him is too busy to think about scoring.”

Coaches don’t think like that anymore, and it’s a big reason why on January 26, 1981, Marcel Dionne led the NHL with 90 points in 50 games (Gretzky had “only” 83 in 47) and Bossy had his 50 goals, while today Chicago’s Patrick Kane leads with 30 goals and 73 points in 52 games … which is actually pretty high by recent low-scoring NHL standards.

January 19, 2016

Of Pucks and Pilots…

In his 1944 autobiography Winged Peace (a follow-up to his 1918 Winged Warfare), Billy Bishop wrote about the interview process when he wished to transfer from the Canadian Cavalry to Britain’s Royal Flying Corps in 1915.

“Can you ride a horse?” Bishop was asked.

He pointed out that he was a cavalry officer.

“Do you ski?”

Bishop heard, “Do you she?” and only later realized what had really been asked. “Yes,” he answered, although he didn’t understand the question … and he didn’t ski. (He did enjoy the company of women, which he thought might be what had been asked of him.)

“How well can you drive a motor car?”

Bishop had never driven a car before. “Very well,” he lied.

“How well can you skate?”

Here was another question he could answer truthfully, although he exaggerated somewhat. “Very well,” he said.

“Did you go in for sports at school–running?”

Bishop was a crack shot with a rifle, but had never been much of an athlete otherwise. Still, he reasoned that the RFC wasn’t going to take the time to check on his records back in Owen Sound. “Yes,” he said, “a great deal.”

The future flying ace was beginning to wonder just how much running, skiing and skating he might be called upon to do, but in 1915 it was believed that people with good balance made good pilots. An ability to withstand cold temperatures was thought to be an asset too. No wonder so many hockey players who enlisted in the First World War found their way into the Air Force. Among them were Hockey Hall of Famers Harry Watson, Frank Fredrickson (both of whom were mentioned in a story recently) and Conn Smythe – as well as the first American-born hockey superstar, Hobey Baker.

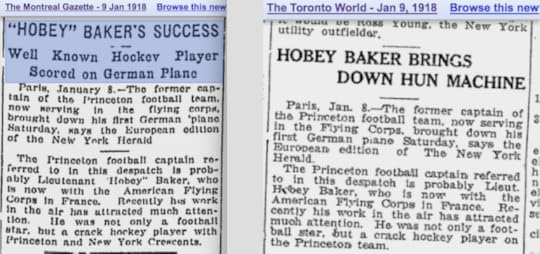

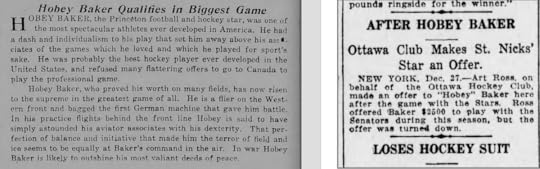

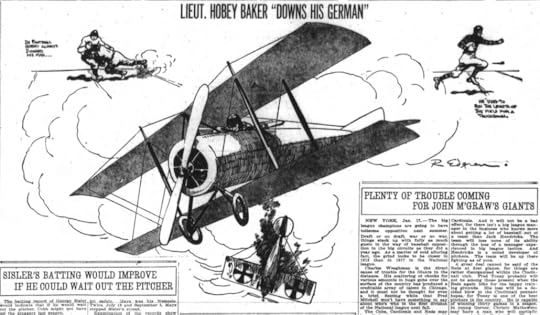

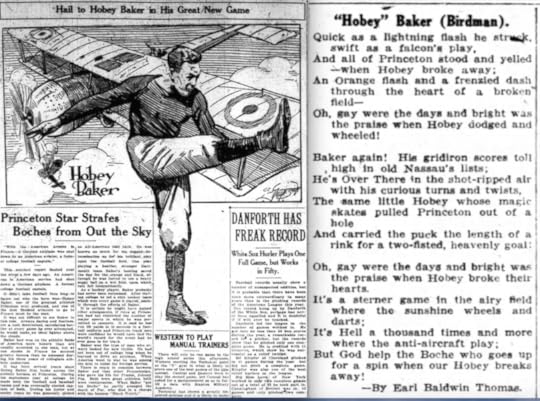

For more on Baker (who died with his orders to return home in his jacket pocket while taking “one last flight” five weeks after the Armistice), you can read his entry on Wikipedia, or the One-On-One Spotlight at the Hockey Hall of Fame, or see the web site for the Hobey Baker Award. But for now, I share with you some newspaper clippings. Most of these were printed 98 years ago this month as Hobey Baker took to the skies over the Western Front.

American Hobey Baker was big news in Canada too.

The story on the left appeared in the New York Tribune on January 14, 1918.

The story on the right had been in the Vancouver Daily World on December 27, 1915,

confirming at least one flattering Canadian offer for Baker to go pro.

From the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, January 20, 1918.

The cartoon appeared in the Washington Herald on January 18, 1918.

The poem had been in the same newspaper on January 13.