Eric Zweig's Blog, page 20

August 16, 2016

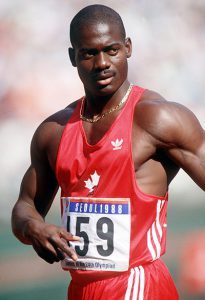

Ben Johnson Owes Me $200

Very exciting to watch the Men’s 100-meter final on Sunday night. Nice to see Andre De Grasse come through on the big stage. Gotta like his chances for gold in 2020 … although a lot can happen in four years.

Exciting as this race was, let’s face it. If you’re old enough to remember, it was nothing like the thrill of Friday night, September 23, 1988. Ben Johnson’s win over Carl Lewis seemed like one of those defining “where were you when” moments we’d always remember. I guess it still is – but not for the right reasons.

Exciting as this race was, let’s face it. If you’re old enough to remember, it was nothing like the thrill of Friday night, September 23, 1988. Ben Johnson’s win over Carl Lewis seemed like one of those defining “where were you when” moments we’d always remember. I guess it still is – but not for the right reasons.

I watched the race late that night Friday night in the basement of a friend’s house. When I woke up on Saturday, still buzzing with the excitement of it, I wrote a story about the history of Canadian sprinters (Bobby Kerr, Percy Williams, Harry Jerome) that I then submitted to the Toronto Star.

There was no email in those days, and I wish I could remember for sure, but I must have driven down to the Toronto Star building later that day, or some time on Sunday, to deliver my story. What I do remember for certain was calling Gerry Hall, the Toronto Star sports editor, on Monday. Did he like the story? Was he interested?

Toronto Star stories on Saturday and Sunday, September 24-25, 1988.

Yes, and yes! But then he told me that they’d just gotten word that someone in Seoul had tested positive for steroids. When it turned out to be Ben Johnson, well … let’s just say there was no longer any interest in my story.

Front page of the Toronto Star, September 27, 1988.

August 3, 2016

Upon Further Review … Fastball (2016)

Barbara and I recently watched the documentary Fastball. Loved it! As a review this past spring in the Los Angeles Times noted, “You don’t have to be a baseball fanatic or for that matter a historian or a physicist to appreciate [this] fittingly zippy tribute to the art of the pitch.”

Narrated by Kevin Costner, filmmaker Jonathan Hock (who directed the ESPN 30 for 30 episode about The Miracle on Ice, among his many credits) uses an impressive cast of baseball Hall of Famers to discuss the fastest pitchers of all time. The film also explains the science of how someone can throw the ball at the very upper limits of human mechanics, and how someone else can still manage to hit a pitch whose speed is at the very edge of how quickly a human being can physically see and react. Fascinating!

Narrated by Kevin Costner, filmmaker Jonathan Hock (who directed the ESPN 30 for 30 episode about The Miracle on Ice, among his many credits) uses an impressive cast of baseball Hall of Famers to discuss the fastest pitchers of all time. The film also explains the science of how someone can throw the ball at the very upper limits of human mechanics, and how someone else can still manage to hit a pitch whose speed is at the very edge of how quickly a human being can physically see and react. Fascinating!

Plenty of today’s fastest pitchers are featured, and there’s also the sad story of 1960s minor league phenom Steve Dalkowski, who could never master his control. But the movie goes all the way back to Walter Johnson, who pitched 20 years in the Majors from 1907 to 1927 with the Washington Senators.

Virtually everyone of his era agreed that Walter Johnson was the fastest pitcher they had ever seen. As early as 1912, his speed was measures scientifically by the U.S. Army … who tracked him at 122 feet per second. That was considered astonishing at the time, but it works out to only 83.2 miles per hour – which struck me as pretty disappointing for such a legendary fastballer. But more on that in a bit.

When Bob Feller burst on the scene 80 years ago this summer as a 17-year-old phenom, he quickly became the new fastball king. Could he throw harder than Walter Johnson? Perhaps you’ve seen the old film clips of Feller firing his fastball alongside a speeding motorcycle doing 86 miles per hour, but Feller was also given a more scientific rating by the U.S. Military. In 1946, his speed was determined to be 98.6 miles per hour. Now that’s more like it!

Feller had begun his career at about the same time that Jesse Owens won the 100 meters at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in a time of 10.3 seconds. The current world record of 9.58 seconds was set by Usain Bolt in 2009. The film points out that if fastballs had improved at a similar rate, there would be dozens of guys throwing 120 miles per hour these days. But, of course, there aren’t.

In 1974, Nolan Ryan became the first pitcher to be clocked while he was pitching in an actual game. Radar tracked him at 100.8 miles per hour in 1974 — making him the fastest pitcher ever. Aroldis Chapman currently has that distinction, hitting 105.1 mph in 2010 and again just recently on July 18. But here’s where the measurements get interesting.

Back in 1912, Walter Johnson’s 83.2 pitch was clocked about 7.5 feet beyond the 60-foot-6-inch distance from the mound to home plate. Feller’s pitch was timed just in front of home plate, and Ryan’s at about 10 feet in front. Today’s modern radar guns record the speed of a pitch at about 10 feet from the pitcher’s hand … some 40 to 58 feet prior to where Johnson, Feller and Ryan were measured. It might not sound like a lot, but any extra distance allows gravity to slow down the speed of the ball as it moves through the air.

Making adjustments for the different distances (1 mile per hour for every 5.5 feet, says the science guy), Walter Johnson’s fastball jumps from 83.2 to 93.8 miles per hour. That’s a little more like it! Feller’s 98.6 improves to an incredible 107.6 mph. And Nolan Ryan? He clocks in at 108.5.

So take that, modern flamethrowers!

July 20, 2016

Crosby, Kessel, and the Stanley Cup

Last Friday and Saturday, Sidney Crosby took the Stanley Cup to his hometown of Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia. It was a busy 24 hours in the Halifax area, as Crosby brought the Cup to a local Tim Hortons (being the most famous graduate of the Timbits hockey program), took it to his local hockey school for children and brought it to a Veterans hospital on the Friday. On Saturday, he paraded with the Cup in Cole Harbour.

Screen shot taken from the Internet feed of Crosby’s Cole Harbour parade.

Crosby did many of the same things during his 24 hours with the Stanley Cup after Pittsburgh’s victory in 2009. Didn’t seem like anyone was tired of it, though!

After Sidney Crosby’s time in Cole Harbour, the Stanley Cup was flown to Madison, Wisconsin, where Phil Kessel and his family spent some time with it in their hometown on Sunday. On Monday, Kessel brought the Stanley Cup to Toronto. People hadn’t seemed thrilled with the idea when the controversial ex-Leaf said he was thinking about a Toronto visit after Pittsburgh’s victory. Even so, Kessel seems to have won the hearts of his detractors with his unannounced visit to share the Cup with the young patients at the Hospital for Sick Children … a Toronto institution he had quietly supported throughout his time with the Maple Leafs.

Screen shots taken from Sick Kids video of Phil Kessel’s visit.

Phil Kessel isn’t the first former Toronto star to bring the Stanley Cup to town after winning it with another team. The very first time the Cup visited Toronto was way back in February of 1901. It came in the care of George Carruthers. Never heard of him? Well, you likely would have if you were a hockey fan in Toronto in the late 1890s. He played with the Toronto Rowing Club and the team from Osgoode Hall, and Toronto newspapers circa 1899 referred to him as the best cover point (defenseman) in the city.

In the fall of 1900, work took Carruthers to Winnipeg. He caught on as a spare player with the Winnipeg Victorias, perennial champions of Manitoba, and was with the team when they defeated the Montreal Shamrocks in a tight series that wrapped up on January 31, 1901. On their way back to Winnipeg with the Stanley Cup, the Victorias stopped off in Toronto to make a pilgrimage to the gravesite of their former teammate Frank Higginbotham, who had died in his hometown of Bowmanville, Ontario, shortly after the Vics’ first Cup win in 1896.

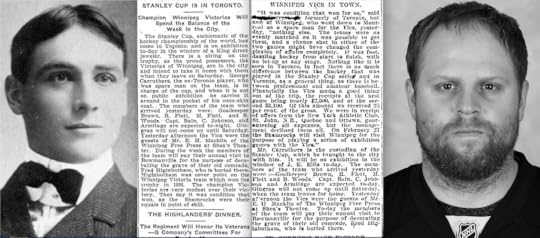

Clippings from the Toronto Star and The Globe, February 5, 1901.

Photo of George Carruthers is from the Society for International Hockey Research.

George Carruthers was “The Keeper of the Cup” during its visit to Toronto, and on February 5, 1901, he put Lord Stanley’s prize on display for the citizens of his hometown in the show window of J.E. Ellis, a jeweller with a store on the corner of King Street and Yonge – less than a five-minute walk from the current location of the Hockey Hall of Fame. The clip from the Toronto Star says of Carruthers and the Cup, “when it is not on public exhibition, he carries it around in the pocket of his coon-skin coat.” The Stanley Cup was a lot smaller in those days, but even so that must have been some big coat Carruthers was wearing!

July 13, 2016

DiMaggio & Williams

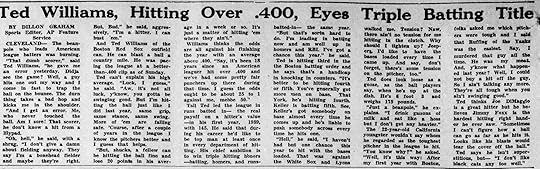

Seventy-five years ago this summer, Major League Baseball witnessed two extraordinary feats. Ted Williams (who was in only his third season, and didn’t turn 23 until August 30) became the last player to hit .400, while Joe DiMaggio (in his sixth season and 26 years old) set a record that is unlikely to be broken with his 56-game hitting streak.

On this day, July 13, 1941, (a Sunday) DiMaggio got hits in both halves of a double header, collecting three hits in the opener and one in the night cap, as the New York Yankees swept the White Sox in Chicago. A crowd of 50,387 – the largest at Comisky Park in six years – saw The Yankee Clipper run his streak to 53 games. He was batting .369 for the season.

The Red Sox also played a double header that day, but Ted Williams wasn’t in the lineup. He’d injured his ankle in Detroit the day before, and missed the twinbill in Cleveland. Williams was actually slumping at the time.

Having gone above .400 on May 25, and reaching a high of .436 on June 6, The Splendid Splinter needed four hits in eight a bats in a doubleheader on July 6 to reach the All-Star break still above .400 at .405. Two days later, he hit a dramatic three-run home run with two out in the bottom of the ninth to give the American League a 7-5 victory over the National League in the All-Star Game at Detroit.

Coming off of that high, Williams went 0-for-4 in a 10-2 Red Sox victory over the Tigers when the season resumed on July 11. That dropped his average to .398. He fell to .397 after going 0-for-1 on July 12 … although he did draw three walks in that one.

The ankle injury he suffered that day kept Williams sidelined until July 16, when he went 0-for-1 as a pinch hitter. Then he sat again until July 19, when he pinch hit in both halves of a doubleheader, going 0-for-1 with a walk and watching his average fall to .393. That was as low as he would go. After singling as a pinch hitter on July 20, Williams returned to the Red Sox outfield on July 22. He had seven hits in 15 at-bats over the next four games to get back to .400 on July 25.

Williams never fell below .400 again, famously entering the final day of the season on September 28, 1941, with a .39955 average but refusing to sit out to protect a mark that would have rounded up to .400. He had six hits in eight at-bats in a doubleheader against the Philadelphia A’s that day and ended the season at .406.

Ted Williams also led the AL with 37 home runs in 1941, while his 120 RBIs ranked him fourth. DiMaggio finished the season third in batting at .357, fourth in homers with 30, and first in RBIs with 125. The Yankees finished the season in first place with a record of 101-53, which had them 17 games ahead of the Red Sox, who were second at 84-70. DiMaggio edged out Williams in MVP voting (the second of three times he’d win the award in his career), and the Yankees went on to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers to win the World Series.

July 6, 2016

Reports of His Death…

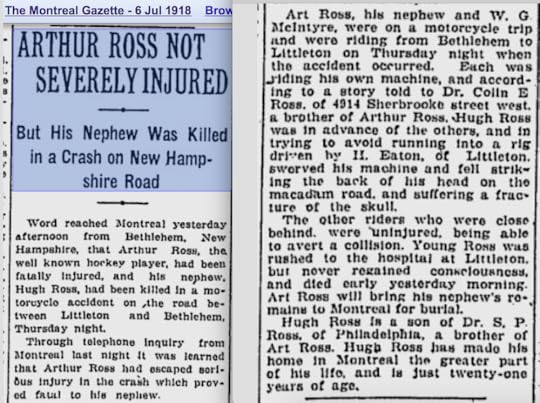

Ninety-eight years ago today, on July 6, 1918 (a Saturday), sports fans reading their favorite newspaper came across reports that Art Ross had either died, or was dying, as a result of injuries suffered in a motorcycle accident. At the time, Ross had just reached the end of a playing career that had seen him widely recognized as one of the greatest players in hockey.

Art Ross excelled at many sports, as this cartoon panel illustrates.

News of the accident first broke in some evening editions on July 5, 1918. The story claimed that Ross and a nephew, Hugh Ross, had been badly hurt during the evening of Thursday, July 4, and that Hugh died of his injuries at 1:30 am on July 5.

By July 6, most newspapers reported that Ross was badly injured, although some claimed that he, too, had died. Below are reports from the New York Times, and from the Evening Tribune in Providence, Rhode Island, which put the headlines over the wrong stories, but reported that Ross had been killed.

That same day, The Toronto World reported in its sports section on page nine that Ross had died, but the same paper had previously reported on page two that he’d suffered no injuries at all.

Fortunately, in Montreal, where Ross’s wife, infant son, mother and brother Colin all resided, the news was cleared up fairly quickly. Art Ross was fine, but the sad truth was that Hugh Ross, a few months short of his 25th birthday, had been killed.

Even so, two days later, on July 8, the Syracuse Herald had a story on its sports page claiming that Art Ross had died.

And some newspapers still didn’t have the facts straight for several more days.

As I wrote in Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins, even now, when a story breaks suddenly, it can be hard to make sense of the conflicting initial reports on the various all-news networks. This was even truer when newspapers were the only real source of news, and so many of them were competing in the same market.

If the story of Art Ross’s death in 1918 had been true, the game of hockey might look very different today. It’s a certainty that its history would.

June 29, 2016

Eric Lindros … Yes or No?

All these years later, it seems there are still plenty of people who hate Eric Lindros.

Spoiled and arrogant? A self-entitled jerk? Maybe. (I don’t know him.) And we’re not going to go into the whole Koo Koo Bananas incident. (I wasn’t there, and he’s certainly not the only rich young man – athlete or not – to act like a jerk. Not that that excuses anything!) But here’s my thinking on Lindros and his parents.

Suppose your son is 18 years old. Just out of high school, or maybe finished a year of university. He knows what he want to do … and he’s very good at it. Doesn’t matter if it’s a lawyer or a plumber or what. Say it’s a plumber. He’s drafted by a plumbing firm. It’s based thousands of miles from where you live, and he probably can’t earn as much money there as he could somewhere else. But he HAS to go. Or, at least, everyone believes he’s got to. And later, if the plumbing firm wants, they’ll trade him somewhere else. Or just let him go.

Would we accept that?

Announcement Monday on the NHL Network that Eric Lindros had been elected

to the Hockey Hall of Fame. He’ll be inducted in November with Rogatien Vachon,

Sergei Makarov and Pat Quinn.

The Lindros family certainly rocked the boat when Eric refused to go to Quebec (and Sault Ste. Marie before that). Lindros said the other day that the reasons had nothing to do with the city, the province or its culture, but with personal differences – likely with Marcel Aubut, who was CEO of the Nordiques at the time and recently stepped down as president of the Canadian Olympic Committee over allegations of sexual harassment.

Whether or not that was really the case, or just revisionist thinking, the Lindros family was fortunate to be in a position where they weren’t like the old-time farm boys or miner’s sons looking for their only way out. Eric Lindros and his parents wanted to have a say in his future. I’m pretty sure my parents would have wanted the same with me. As it was, my family certainly did a lot to help when I was getting started in my work. Wouldn’t you do the same for your kids if you were in a position to? And yet people hated the Lindros family for it. Many still do.

But, of course, sports aren’t like being a plumber. Or a lawyer. Or a writer. These athletes should consider themselves lucky that they get paid to play games! They should do what they’re told!

And yet, we all look back at Gordie Howe and we think how terrible it was that such a great athlete was taken advantage of so badly by the people in charge of the game he excelled at. A team jacket as a signing bonus; a thousand dollar raise each year; a salary kept artificially low so that other teams could say to their stars, “how can we pay you more than Gordie Howe?”

It was all about who controlled the money, and who had the power. That’s why guys like Punch Imlach and Jack Adams could walk around with train tickets to minor league towns sticking out of their pockets, terrifying young players into towing the line.

Yes, things are better now. Players can make tens of millions of dollars. But there’s still no one in management really looking out for their best interests … unless they also serve the best interests of the team. As I’ve said before, I do have a hard time rooting for people half my age making more money per game than I do in a year, but if there really is that much money out there, I’d rather see the players getting their fair share.

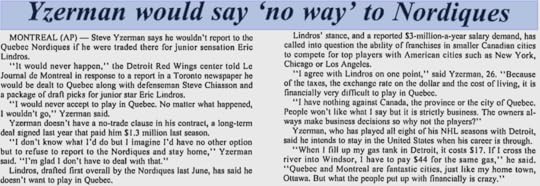

In this Associated Press report from Montreal on August 16, 1991 – two months after

that year’s NHL Draft – Steve Yzerman said he didn’t want to play in Quebec either.

All that aside – and you’re certainly free to disagree with me – there’s still the question of whether or not Eric Lindros the player is worthy of induction to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Love him or hate him, in the early days of his career – before all the concussions – Lindros was certainly living up to “The Next One” hype. In his first six seasons, from 1992 to 1998, he played 360 games (injuries had already cost him nearly 100 games) and had accumulated 507 points.

In the NHL Official Guide & Record Book, there is a listing for the Highest Points-Per-Game Average, Career (Among Players with 500-Or-More Points). At the time Lindros had reached those 507 points, his points-per-game average was 1.408. If he’d kept that up for his entire career, Lindros would still be a long way behind Wayne Gretzky (1.921) and Mario Lemieux (1.883), who hold down the top two spots, but he would only be slightly behind #3 Mike Bossy (1.497) and would rank ahead of the 1.393 mark of the #4 player … Bobby Orr.

If Lindros had managed to stay healthy enough to play 1,000 games at that scoring pace, he would have had 1,408 points in his career. That would rank him 20th in NHL history despite playing significantly fewer games than anyone else in the top 20 except for Mario Lemieux, who ranks eighth all time with 1,723 points while playing only 915 games.

Even at his final career scoring pace of 1.138 (865 points in 760 games), which was much diminished due to his injuries, if Lindros had managed to reach 1,000 games his 1,138 points would place him 54th in NHL history (two spots ahead of Bossy) despite playing far fewer games than everybody ahead of him except Lemieux and Peter Stastny (1,239 points in 977 games.)

But, of course, those are pretty big ifs!

I’m not sure the Hockey Hall of Fame should be rewarding anybody for the potential of what might have been … but since Peter Forsberg and Pavel Bure are already in with pretty comparable statistics, and Cam Neely is in with much weaker career numbers, it’s hard to make the case for keeping Lindros out.

June 22, 2016

The More Things Change…

Well, it’s June 22 and the weather in these parts has gotten pretty summery – though it’s a little bit cool today. But it’s Canada so there’s still a lot of hockey going on. The Leafs made a big trade for a goalie this week, expansion to Las Vegas is expected to be announced, and the NHL Awards from there will be handed out tonight. Still, the biggest news (though as yet unconfirmed) is that Ron MacLean could be back as host of Hockey Night in Canada, replacing George Stroumboulopoulos.

I do enjoy watching Ron MacLean on television, and, personally, he’s been very nice to me. I’ve never met Strombo, but if truth be told, I think he did a decent job … I just don’t like his sports-hipster style. And it seems that I’m not alone. Even so, Strombo isn’t the real problem. As Vijay Menon said in the Toronto Star yesterday, would the TV ratings for hockey these days be any different “if HNIC were co-hosted by the ghost of Foster Hewitt and Paulina Gretzky in lingerie?”

Ratings are off (sorry, rest of Canada) because the Leafs have been terrible. And it didn’t help that no Canadian team made the playoffs this year. Yet the biggest problem is that the game isn’t as much fun to watch as it used to be. And that’s not just cranky “the game was better when I was a kid” talk. Yes, players are bigger, stronger, and faster than ever … but I’m not the first one to suggest that maybe they’re moving too quickly now. So fast, in fact, that there’s not enough time to be creative with the puck. There’s not much room for it either. The result is that not enough goals are being scored.

I’ve written about bigger nets, and 4-on-4 hockey in the past, but really, if I could do anything I wanted to fix things it would be to reduce roster sizes. The Players Association would never let it happen, but if teams could only dress 10 forwards and 5 or 6 defensemen (like they used to), the game would slow down a little bit, which would open up more space and allow for more time so we’d see more goals scored. But since that’s impossible, all we’ll get is yet another minor reduction in the size of goalie equipment. It’s better than nothing, but this is an issue that goes back a lot further than you might think.

Take a look at this cartoon from the Pittsburgh Press on March 22, 1908.

I posted the segment at the bottom of this drawing, showing Art Ross and his wiggly moves, on Facebook recently. Today, however, I call your attention to the central feature – Montreal Wanderers goalie and future Hockey Hall of Famer Riley Hern.

Despite the fact that he wears skinny cricket pads, regular playing gloves, no mask (but a jaunty hat!), and is not allowed to fall to the ice to make a save (note the illustration in the top left), clearly what struck Artist Rigby about Hern was the bulky padding he was wearing on his upper body. He looks like a modern lacrosse goalie … or the Michelin Man, as hockey goalies these days have sometimes been called. As it so happens, it’s the size of goalie pants and upper-body protection the NHL plans on slimming down next season.

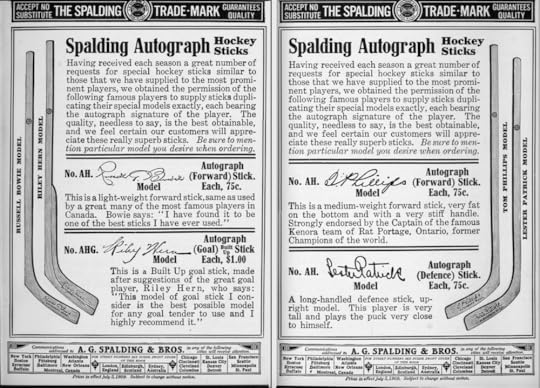

And check out the “giant” goalie stick Riley Hern lent his name to in this Spalding ad from 1909.

No one’s going paddle-down with that … although, in truth, my real point in displaying this ad is just that I think it’s amazing that future Hockey Hall of Famers were marketing their own brand of sticks as early as 1909!

June 14, 2016

Mr. Hockey

Congratulations to the Pittsburgh Penguins, but although it’s already been a few days, it didn’t seem right to write about anything other than Gordie Howe this week.

I only met Gordie Howe once, back in 1993 when I worked at the Hockey Hall of Fame. I’ll admit, it didn’t have the same feeling of meeting royalty that my similarly brief encounter there with Jean Beliveau had. It felt more like being with your favorite uncle. Like he already knew you and was happy to share a funny story. (We were standing near the Stanley Cup, and he was grumbling good-naturedly about how he’d only won it four times, while Henri Richard had won it 11 times.)

Gordie Howe set records in his day that seemed unbreakable. Some of them never have been. Still, it’s interesting to note that, before the nickname made its way to him, there were several men who were already known as “Mr. Hockey.” As early as 1933, it seems that Conn Smythe was going out of his way to discourage New York writers from considering Lester Patrick to be Mr. Hockey.

Lester Patrick as Mr. Hockey in The Ottawa Journal, April 18, 1933.

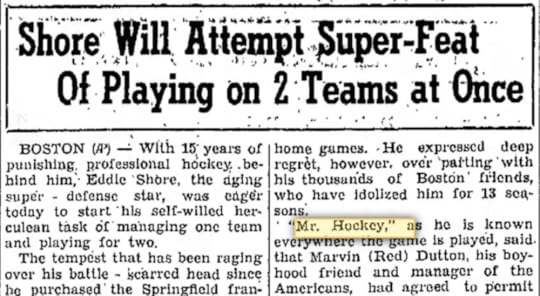

In my research for my book on Art Ross, I came across several references to him as Mr. Hockey … in the Boston-area, anyway. And Bruins great Eddie Shore was also known as Mr. Hockey “everywhere the game is played.”

Eddie Shore as Mr. Hockey in an Associated Press story, January 26, 1940.

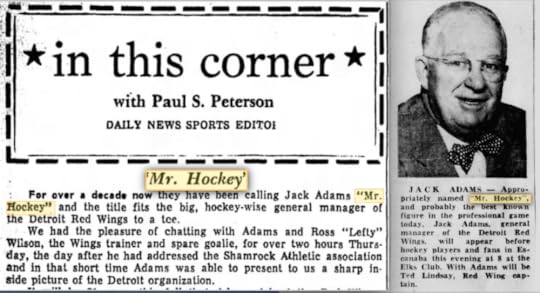

Even in Detroit, Jack Adams was known as Mr. Hockey long before anyone in town had ever heard of Gordie Howe. Adams, who was coach and/or general manager of the NHL’s Detroit franchise from 1927 to 1962, was dubbed Mr. Hockey in the early 1940s.

Jack Adams is referred to as Mr. Hockey in a couple of Michigan newspapers

in the 1960s; The Ludington Daily News and the Escanaba Daily Press.

The earliest reference to Gordie Howe as Mr. Hockey that I’ve come across dates back to March of 1953. Nels Stewart (an NHL star of the 1930s and ’40s) was referring to the fact that while Maurice Richard might have recently surpassed Stewart’s NHL record of 324 career goals, Howe would likely pass them both some day.

The story on the left appeared in Toronto’s Globe and Mail on March 7, 1953.

The one in the right was in papers across North America on October 21, 1957.

But Stewart’s quote seems to categorize Howe as just one of several Mr. Hockeys, Maurice Richard among them. The name doesn’t really seem to attach itself to Howe until after Jack Adams retired from the Red Wings in 1962, as I haven’t been able to find it again in reference to Howe until 1963. And, really, it doesn’t seem to come into widespread use until after Adams died on May 1, 1968.

The story on the left appeared in many Canadian papers on

March 6, 1963. The one of the right ran in papers on November 3, 1969.

Others have already written about this since Friday, although I’m not sure I’ve seen it put as directly as I’m about to right now: Gordie Howe is the reason we think of hockey players at their best the way we like to. The stereotype – which is generally true – is that hockey players are more approachable than other athletes; and we like to think of the best of them as being as tough as they are talented on the ice, but always humble and accommodating off of it.

That was Gordie Howe. He truly was “Mr. Hockey.”

June 9, 2016

Who Needs A Pair?

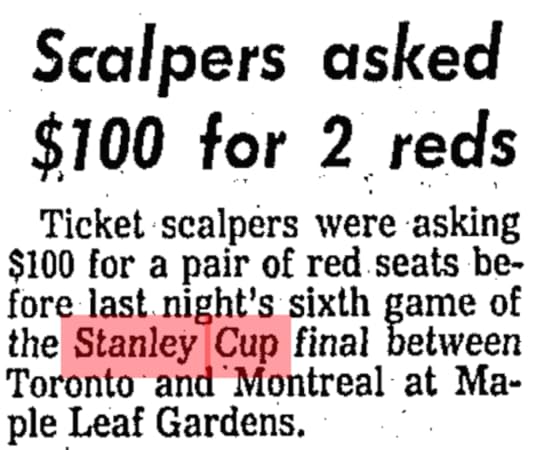

The Stanley Cup Final could wrap up tonight with a Penguins win on home ice. Pittsburgh’s three previous Stanley Cup victories (in 1991, 1992 and 2009) all came on the road. In fact, no major pro Pittsburgh sports team has won a championship at home since the Pirates in 1960. So it’s no surprise that scalpers are asking a lot for this game. Highest price I saw last night for a single seat at ice level was nearly $12,000! Who knows if they’ll get it, but they’ll certainly get a lot more that what the scalpers wanted the last time Toronto won the Stanley Cup according to The Globe and Mail on May 3, 1967.

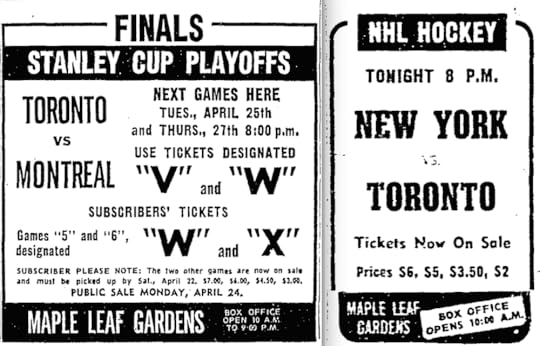

Check out the face value of 1967 Leafs tickets shown in the ads below. Notice in comparing the two that they raised the price a whole dollar across the board for the playoffs! And for those who don’t know, the reds being scalped in the story above were the best seats the house at Maple Leaf Gardens back then.

For comparison, here’s the listed price for tickets in Pittsburgh during the postseason:

According to what I could find online, the median household income in the United States was about $7,200 in 1967. Canada was likely pretty much the same. The most recent data for the U.S. shows about $54,000 as the median income in 2014. Just using some basic math, it seems to me that while income has increased by a multiple of 7, the face value of a top-price Stanley Cup ticket is 77 times more!

So my guess would be there were a lot more working stiffs in 1967 who could afford $7 for a ticket then there are who can afford $544 today. And even $50 on a yearly income of $7,200 would be about half a week’s salary for half of that $100 pair. A half-week’s salary of $12,000 today would net you about $1.2 million per year! I guess there are plenty of people who actually make that kind of money … but I sure don’t!

June 1, 2016

Stanley Cup Play in the City by the Bay

After tonight’s game between the Penguins and Sharks, the Stanley Cup scene shifts to San Jose for games three and four on Saturday and Monday nights. While this is the Sharks’ first appearance in the Stanley Cup Final in their 25 seasons in the NHL, this will not be the first time that Stanley Cup-calibre hockey is being played in Northern California.

Ninety-nine years ago, in 1917, just days after the Seattle Metropolitans defeated the Montreal Canadiens to become the first American-based team to win the Stanley Cup, the two teams met again in a best-of-three “World Championship” series in San Francisco.

I wrote about it for The Hockey News in September of 2012 after the Los Angeles Kings won the Stanley Cup for the first time. The story works even better now, but rather than write it all again, you can click here to have a look at the original. You can also check out the images below…

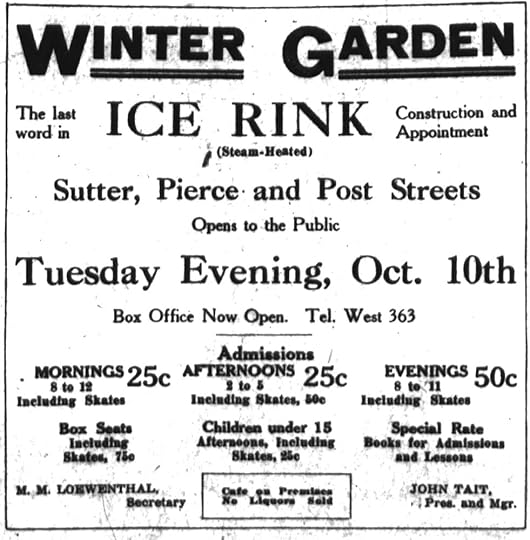

(And just to complete the story, it appears that by the fall of 1918 the Winter Garden Ice Rink where these games were played was converted to a dance pavilion, which then disappears from the record around 1927. Winterland, which was an ice rink later converted to a famous concert hall, seems to have been built on or near the same site in 1928.)

Ad for the opening of the Winter Garden Ice Rink,

the San Francisco Chronicle, October 7, 1916.

San Francisco Chronicle stories, October 10 and 11, 1916.

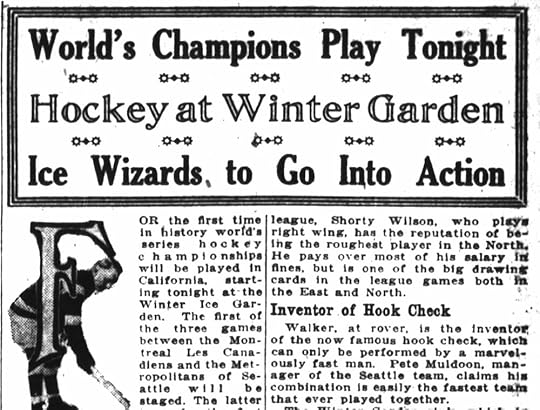

Ad for the first game between Seattle and Montreal,

The San Francisco Chronicle, March 30, 1917.

Headline and story segment hyping the first game between

Seattle and Montreal, the San Francisco Chronicle, March 30, 1917.

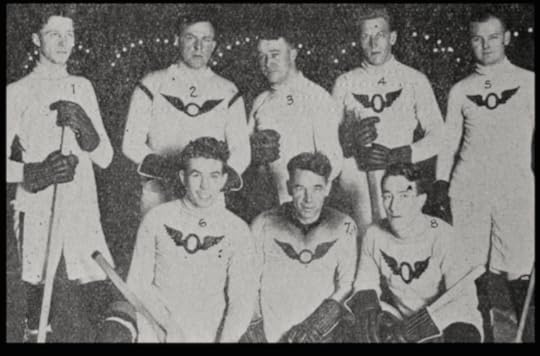

The Seattle Metropolitans and the Montreal Canadiens on the ice at the Winter Garden.

San Francisco’s Olympic Club was one of many amateur hockey teams to play

at the Winter Garden during the fall and winter of 1916-17.

Note the curving lights that are also visible in the above picture.

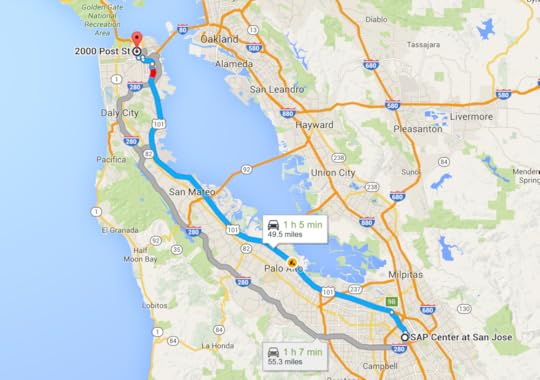

Depending on traffic, this year’s Stanley Cup games will be

little more than an hour away from the site of the Winter Garden.

The Winter Garden was right in the heart of San Francisco,

bordered by Sutter, Post, Pierce and Steiner Streets.

This apartment complex (which appears to have been extensively renovated in recent years) stands today in San Francisco on the site that was once the Winter Garden and Winterland.