Eric Zweig's Blog

October 9, 2025

OK, Blue Jays!

Well, I’ve avoided writing about the Blue Jays all season long. Truth is, I never believed they could do this. I tried to put my skepticism aside and just enjoy it. But, any time trouble arrived, I’d think, ‘That’s it. They stink. Can’t keep it up.’ I didn’t think they could hold off the Yankees down the stretch. I was pretty nervous heading into the Division Series too. Don’t think I’ve ever been so happy to be wrong!

Our family has had Blue Jays season tickets pretty much since the moment they went on sale prior to the first season in 1977. We were all there, in the snow, on Opening Day. I was at every opener until 2018, when Barbara was diagnosed with cancer. I’d even skipped school again in 1980 to attend the makeup game after the official opener was rained out. My mother (Joyce) and brother Jonathan still have their home opener streaks in tact.

Me, with my brother Jonathan, at Game 2 on Sunday afternoon.

Me, with my brother Jonathan, at Game 2 on Sunday afternoon. With the Jays wearing their white-paneled hats for luck, I had to

dig out my original fitted cap from the summer of 1977!

My mother is the reason our family became Blue Jays crazy. (Many of you will have seen her TV appearances over the years, including one on the CBC last week. There might be another on CTV this evening!) My father was a sports fan, but my mother was a baseball fan! She always says it was the only game she really understood as a girl. She used to attend the minor-league Toronto Maple Leafs baseball games in the 1950s and root for the Brooklyn Dodgers against the New York Yankees watching the World Series on television.

Vladimir Guerrero reaching home plate after his grand slam on Sunday.

Vladimir Guerrero reaching home plate after his grand slam on Sunday.Of course, I watched plenty of games this year — and attended a few — but I wish I’d more fully embraced the team. I should have! They play the type of baseball I really enjoy … putting the ball in play and making things happen, as opposed to slugging and strikeouts. And they really do seem to like each other. But after the playoff flame-outs of recent years, and the terrible season last year, I didn’t think they’d done nearly enough to turn things around. (I certainly wasn’t alone with that thought!) The Jays got off to a good start, but then sort of fell apart and it was easy to believe it would be another frustrating season.

The last pitch last night. (Took the picture off my TV.)

The last pitch last night. (Took the picture off my TV.)I was hopeful Bo Bichette would bounce back, and even though Vladimir Guerrero has mostly been good-but-not-great (and I have trouble wrapping my head around anyone making $500 million!), I figured they really did have to re-sign him. Still, I wasn’t very optimistic. My friend Leslie was an early believer. I warned her not to get too excited, but it turns out she was right!

Like I said, I don’t think I’ve ever been so happy to be wrong.

Doesn’t get much better than beating the Yankees!

And now, it’s on to the American League Championship Series.

Whether it’s Detroit or Seattle, it should be exciting!!

Spraying champagne after the game. (Again, taken while watching TV.)

Spraying champagne after the game. (Again, taken while watching TV.)

September 9, 2025

Memories of Ken Dryden

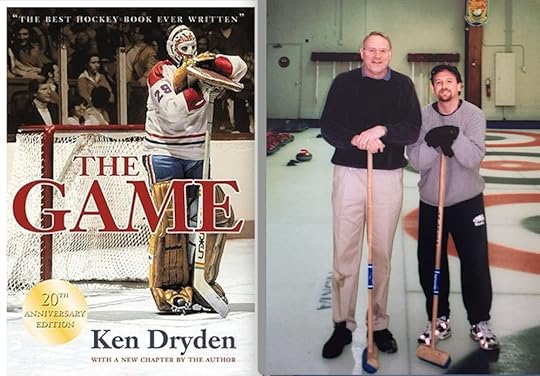

I knew Ken Dryden, but not very well. I’ve been a little bit surprised by how the news of his death has affected me. As I said to someone on Facebook recently, we (I) am now at an age where the heroes of our youth are passing away. It’s a sad reminder of how quickly life goes.

Ken became (and remained) good friends with my NHL publishing boss Dan Diamond during Ken’s time as president of the Toronto Maple Leafs from 1997 to 2004. We at Dan Diamond and Associates did a lot of work with Ken when the Maple Leafs were moving from the Gardens to the Air Canada Centre. Dan also worked with Ken during his political career and we were all at the event at Ken’s old elementary school in 2006 when Ken announced he was running for the Liberal leadership.

I met Ken a handful of times over the years, when he would attend parties Dan held either at home or for the office. In more recent years, I would sometimes call or email him if I wanted advice or an opinion for something I was working on. He was usually quite accommodating. The last time he and I talked was in early May. His voice sounded raspy, and he said he hadn’t been well, but he gave no indication of anything worse than that. Ken had called me about my interest in something an old friend had come to him with. I was a little surprised it wasn’t something he wanted to get involved with himself … but, I guess, we now know why.

When Ken attended some of our Dan Diamond curling parties,

When Ken attended some of our Dan Diamond curling parties, my brother Jonathan wanted a picture of the two of them leaning

on their curling brooms a la the classic Dryden goalie stick pose.

When Ken called in May, I took the opportunity to ask him something for a book I’m working on that I hadn’t previously because (more big name drops!) I had already been in touch with Scotty Bowman and Dick Irvin about it. My question was, did he remember anyone referring to the line of Guy Lafleur, Steve Shutt and either Pete Mahovlich or Jacques Lemaire as The Dynasty Line during the Canadiens’ 1970s Stanley Cup Dynasty. Like Bowman and Irvin, Ken had never heard that term. Ken said something along the lines of “it would have been silly to call them that then.” Then I quoted him something from an Al Strachan article in the Montreal Gazette from the 1975–76 season. Pierre Bouchard had apparently dubbed the line of Lafleur, Shutt and Mahovlich The Donut Line as a shot at Mahovlich, “because the line had no center.” Shutt responded by saying Mahovlich called them The Helicopter Line “because they had no wings.” Ken laughed and said, “that sounds like Shutty!”

Ken was always very approachable and I remember at our office Christmas party in 2002 mentioning that I had recently watched the DVD of all the games of the 1972 Canada-Russia series, which had come out around then. He told me he’d never seen it and that he didn’t like to watch any old footage of his games, which I’ve read again recently in various memories of him. (I do believe he finally re-watched the 1972 games for his 2022 book on the 50th anniversary of the series.) He was pleased when I told him the intensity and skill displayed in the series still held up, and then I screwed up my courage to ask him something I’d long wondered about. How come he, and some of the other players, who had spent time with the Canadian National Team hadn’t been able to convince their Team Canada teammates how good the Soviets really were? Ken said something along the lines of, “I just thought NHL players were that much better.”

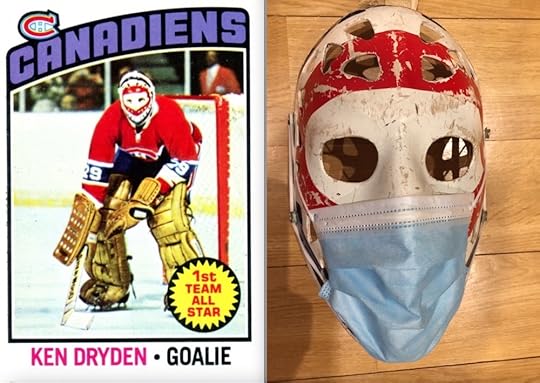

I’ve kept this package of Ken Dryden’s Big Canada Chocolate Chip Cookie since 2006!

I’ve kept this package of Ken Dryden’s Big Canada Chocolate Chip Cookie since 2006!One thing I never had the guts to tell Ken was how much I didn’t like him when I was a boy! In truth, I did like him at first. Like most people, I became aware of him during the 1971 playoffs when — though not yet even officially considered an NHL rookie — he led the Canadiens to that huge upset of the Bruins and then all the way to a Stanley Cup championship. Of course, I was seven years old at the time, and I can’t really say anymore how much I actually remember versus how much I now know. And, of course, there was his role in the 1972 series. But by the time I was 12 years old, the Leafs had Darryl Sittler, Lanny McDonald, Borje Salming et al and I was hooked on my hometown team.

I was barely 13 when Mike Palmateer became the Leafs goalie, and I was way more into him that I was into Ken Dryden! The two playoff losses to the Canadiens in 1978 and 1979 didn’t help … but, I’m sure, had I told Ken that young me had hated him, he wouldn’t mind. He was a sports fan above all and would have understood childhood loyalty. After all, he had that quote about the best era of the game being “whenever you were 12 years old.” (Though you sometimes see the age recorded as young as 10 or 11.)

I’ll conclude this with an email/phone conversation I had with Ken back in 2010. This was regarding some early work that would lead towards my Stanley Cup books for Firefly in 2013 and 2018. I’ll begin with an except from my email to him, and then my notes based on our phone conversation.

I was one of several people Ken sent this photo to to get the word out

I was one of several people Ken sent this photo to to get the word outabout the importance of wearing masks during the Covid pandemic.

Dear Ken,

The best of the season to you and Lynda and your family. I hope you are all well … and that you will have a few minutes to spare over the holidays to think about this question I have for you…

When I first started pitching [my Stanley Cup history book] to a few publishers, I got a lot of responses along the lines of “this is a great book that somebody should do” but no commitment to take it on, or, worse yet, “hockey fans don’t like history, and history buffs don’t like sports.” Well, as one hockey fan who loves the history of both the game and his country, I think they’re wrong!

Though I’m honestly not sure how I’d fit it into the narrative as I’d like to do it, I have been asked to consider adding some sort of “what my Stanley Cup win meant to me” angle … and so I am wondering what sort of connection, if any, the players I grew up watching or the ones playing now have to the history of the Stanley Cup.

When you won, either for the first time in 1971, or as part of the “dynasty” later in the decade, or when you first saw your name engraved on the trophy, did you personally feel any kind of connection to the history of the game? Or, if not at the time, do you look back on your Stanley Cup wins now as something that will forever make you a part of hockey history? Do you think other players have felt this? Is this an angle at all worth pursuing in a book about the early history of the Stanley Cup?

A response by email is certainly sufficient, but if this is something you’d be at all interested in talking about in any more depth, please feel free to call me at home.

Thanks, Eric

Notes from Ken’s phone call:

Unreal feeling joining the Canadiens … like, “if this is the real Canadiens, why am I here?”

Even more of a disconnect in the playoffs. “If this is the real Stanley Cup … Conn Smythe Trophy … then why am I winning it?”

Being in the NHL didn’t really hit him until coming home after game seven in the first round against Boston and there were big crowds at the airport.

Didn’t feel a connection to history when they won. He never felt there was a quiet moment where you took a deep breath and thought, “this is what the Rocket did.”

Parades helped to make it feel real.

How each team got there was what really mattered, and the harder the journey the more rewarding.

Best was in 1976. “The quest.” He felt that he, and probably everyone, starting preparing for that as soon as they were eliminated from the playoffs in 1975. Thought about it all summer. Played Philly tough in the preseason (see Denault book), set the tone in regular-season games. “Felt like a full-season quest.”

As to history, Ken only had a very general awareness of the challenge history … and thought the NHL took over the Stanley Cup right way in 1918. Feels the seeds of the modern sport (all modern NA sport) where sowed in the 1920s. Probably due to radio. Created first media stars (Babe Ruth, Red Grange, Bobby Jones et al.)

Not sure any player feels the connection to history. Thinks modern players have been programmed to give the answer you’d want to hear (“I thought about my heroes when I lifted the Cup…” but he doesn’t believe they really do). You’d really have to dig to get a thoughtful answer about what they really felt.

August 6, 2025

The Pride of Paris, Ontario? There’s an Apps for that!

These days, whenever I post a story on my web site, I feel like it might be the last one I ever do. Like, I’m all out of ideas and this is it. It’s been a long time since I’ve actively searched out subjects for these stories … but, then, something always comes up. Usually it’s a current event that reminds me of something historic. Sometimes it’s something in my own life. Whatever it is, an idea for a story will suddenly seize me. Then, I go down too many rabbit holes trying to put it all together before reining it in. And then, a post. Like today’s.

Lynn and I recently had a short getaway in Paris. (Not THAT Paris — although, as some of you will remember, we were in France in May of 2024 and it was lovely.) This was Paris, Ontario, and until we arrived and I saw a sign for the Syl Apps Community Centre, I’d forgotten the long ago captain of the Toronto Maple Leafs who was voted the second greatest player in franchise history for the team’s centennial in 2017 was from there.

Syl Apps plaque in Paris, Ontario and Apps with the Hamilton Tigers (SIHR).

Syl Apps plaque in Paris, Ontario and Apps with the Hamilton Tigers (SIHR).Charles Joseph Sylvanus Apps was born in Paris on January 18, 1915. After being named the NHL’s rookie of the year for the 1936–37 season, his hometown honoured him on the night of June 11, 1937, as part of a three-day Lions Club Carnival. That season, NHL president Frank Calder was encouraged by Toronto Star sports editor Andy Lytle and Maple Leafs owner-manager Conn Smythe to donate a trophy for the winner of the annual (since 1933) Canadian Press sportswriters poll selecting the league’s top rookie. Perhaps this was because the Leafs boasted rookie stars Apps, Gord Drillon and Turk Broda that season!

As the story goes, Frank Calder was en route from Montreal to Paris by train with his trophy when he realized something. Unlike the NHL’s other individual awards — at the time, there was just the Hart for MVP, the Lady Byng for sportsmanship, and the Vezina for the best goalie — a player named the NHL’s best rookie could never win that award again. So, the league boss decided he would give Syl Apps the Calder Trophy to keep. Every year after that until his death in 1943, Calder bought a new trophy and presented it to the NHL’s top rookie. Official approval for the permanent Calder Memorial Trophy was given by the league governors at an NHL meeting in Montreal on September 7, 1945.

Brantford Expositor, June 11, 1937.

Brantford Expositor, June 11, 1937.Apps received the first Calder Trophy at a star-studded gala held at the Paris Arena. Unknown to me when Lynn and I visited, the Paris Arena was originally built in 1921–22 … and is still housed within the Syl Apps Community Centre! It now boasts a much more modern brick exterior, and there’s no longer a hockey rink inside, but the old arena space is used for indoor soccer and still features the same wooden beams and ceiling/roof from the early days. From behind, the modern community centre still looks looks like an old-time auditorium.

Syl Apps played 10 years with the Toronto Maple Leafs from his rookie season of 1936–37 through 1947–48, missing two years due to military service in World War II. He was named captain in 1940 and led the Leafs to Stanley Cup victories in 1942, 1947 and 1948. At 6 feet tall and 185 pounds, he was big and handsome and played a stylish game. (For those old enough to remember, think Jean Béliveau.) Apps is one of few Maple Leafs of whom it can honestly be said he was among the very best players in the NHL in his day. He never won the Hart Trophy as MVP, but in his first seven seasons before the War, Apps was second in voting three times and third in voting twice.

Brantford Expositor, June 12, 1937.

Brantford Expositor, June 12, 1937.Apps likely started playing hockey as a young boy. He played midget hockey in Paris as a 14-year-old during the winter of 1928–29 and was a member of the local Ontario Hockey Association junior team in 1930–31 when he turned 16. There were reports in the spring of 1932 that after high school Apps would attend Western in London, but that fall he left Paris for Hamilton to attend McMaster University. He would play hockey there, as well as football, and though he’d apparently played little of that sport in Paris (he did play basketball in high school), Apps became quite the star on the gridiron. He was also on the McMaster track team, where he competed in the pole vault which he’d taken up in high school at least as early as 1928. He also competed in the long jump and the high jump as a student in Paris, and while still in high school he placed second in the junior division in a pole vaulting competition in Hamilton in conjunction with the first British Empire Games (now the Commonwealth Games) in 1930. Four years later, Apps wasn’t just the best pole vaulter in Canada but won the gold medal on August 6, 1934, at the second British Empire Games in London, England.

Brantford Expositor, October 1, 1927. The photo is from August 27, 1930.

Brantford Expositor, October 1, 1927. The photo is from August 27, 1930.While in his final year at McMaster, Apps joined the Hamilton Tigers hockey team for the 1935–36 season. He led them to the OHA senior champion and was the top scorer in the province. At the end of April, Apps traveled to Los Angeles for hockey (and lacrosse) games with a Canadian Legion team from Hamilton, although he and teammate Norval Williamson flew home early to complete their final university exams.

By the spring of 1936, it was well known that several NHL teams wanted Syl Apps and the Maple Leafs had put him on their negotiation list. Still, he had no interest in turning pro before taking his shot at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. (There had been stories he was being considered as an addition to the Canadian Olympic Hockey team earlier in 1936, but he hadn’t wanted to interrupt his studies.) In July, Apps won the Ontario championship in the pole vault with a jump of 12 feet, 11 inches. Barely a week later at the Canadian Olympic trials in Montreal, he jumped 13 feet and a half inch to win that competition. A few days later, Apps was on board the Duchess of Bedford with the rest of the Canadian Olympic team sailing for France before a train ride to Berlin.

The Montreal Star, July 13, 1936. Syl Apps is #3.

The Montreal Star, July 13, 1936. Syl Apps is #3.Canadian papers noted Apps would likely need to improve his height by at least a foot to earn a medal in the pole vault in Berlin. On July 4, 1936, American George Varoff had set a new world’s record of 4.43 meters (14 feet, 6 1/2 inches) … although a few days later he slumped to fourth place at the American Olympic trials and didn’t even make the U.S. team. In the Olympic final on August 6, 1936, another American, Earle Meadows, won gold with a jump of 4.35 meters (14 feet, 3 1/4 inches). Apps did improve his performance by nearly a foot, clearing an even 4 meters (14 feet, 1/8 inches) but that was only good enough to tie for sixth place. (In reading about Apps over the years, I’d always assumed it was a two-way tie for sixth place, but he was actually one of 11 men tied at 4 meters.)

On August 25, 1936, Syl Apps arrived back in Canada aboard the Duchess of Richmond with about one-third of the Canadian Olympic team. He said he’d made up his mind not to try out for the Hamilton Tigers football team that fall and there were also reports he’d turned down offers from several hockey teams in London, England while he was in Europe. Football in Canada and hockey in England were strictly amateur at the time, yet Apps still hadn’t decided whether to go pro with the Maple Leafs. He made up his mind soon enough, signing a contract on September 2, 1936.

Colourized photograph of Syl Apps from

Canadian Colour

, 2015.

Colourized photograph of Syl Apps from

Canadian Colour

, 2015.“In our circle,” Apps would tell Stan Fischler for his book Those Were The Days (1976), “professional athletes were not looked upon as the right sort. But economic conditions were poor at the time and jobs were scarce. Molly [girlfriend Molly Marshall] told me the chance with the Leafs was a golden opportunity. I decided to sign although I was scared when I went to see Mr. Smythe.”

He would have to give up his amateur athletic pursuits, but “Sylvanus Apps loves hockey above all other games,” reported Andy Lytle in The Toronto Daily Star on October 28, 1936, a few days before the start of his rookie season.

The decision worked out pretty well.

July 29, 2025

Jaws: 50 Years Later

I’ve been going to the movies for longer than I can remember. I’ve been told the first movie I saw was Mary Poppins. My parents loved movies, but given that Mary Poppins came out in 1964, I have a hard time believing they took me to see it when I was 1 year old. Perhaps it was still playing somewhere in Toronto a few years later. I do remember seeing Oliver! in a giant downtown theater. It came out in 1968, a little before I turned 5. I’m guessing I saw it some time in the spring of 1969, but again it could have been later. I still watch at least some of it whenever I notice it’s on TV. I must have seen The Love Bug around that time, and I also retain a warm spot in my heart for Herbie the Volkswagen Beetle.

I saw a lot of Disney live-action films in the early 1970s, and others like them. Some have been remade in recent years, but I’m not sure too many critics were impressed at the time. Still, they were fun for a young kid.

One of my first truly grown up movie was Jaws, which I saw very shortly after its release on June 20, 1975. (I also saw The Sting, which came out in 1973. I think I saw it in the theater, so it might have been my first, but I may actually have seen it a few years later.) I definitely saw Jaws with a few friends from school at a matinee a day or two after the end of Grade 6. I was 11, but some in the group were probably 12.

Jaws was terrifying, but thrilling too! I know I didn’t sleep very well that night and I distinctly remember keeping my arms and legs underneath the covers. (Everyone knows covers can save you from ghosts and bogeymen, so it felt a lot safer to keep my limbs tucked under the sheets and blanket rather than dangling off the side of the bed.) Still, seeing Jaws did NOT keep me out of the water at the cottage that summer … so take that!

Screenshot

ScreenshotAnyway, I recently watched Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story on National Geographic TV. It was great! And it reminded me that a few years ago (in the fall of 2017, it turns out), after having done a couple of books for National Geographic Kids, I wrote a proposal for them for a children’s book about the history of the movies. It fell through about a year later. But, I re-read my proposal and liked it, so I thought I’d post some of it. Here it is…

Chapter 1: The Birth of the Blockbuster

Auguste and Louis Lumière were brothers born in France in the early 1860s. Their father, Antoine, was an artist who gave up painting to take up photography. The two Lumière boys became crazy about cameras. Auguste and Louis were smart at science and brilliant at building things. By 1895, they had built a new machine they called the Cinématographe. It was a device capable of taking numerous pictures and projecting them as moving images.

The Lumières’ new device was a huge improvement over similar machines by other famous inventors. Thomas Edison had already created a machine to show moving pictures, but they could only be seen by one person at a time looking through a small viewing window into a large wooden box. The pictures shown with the Cinématographe could be seen on a screen by a large audience. The Lumière brothers were also the first people to film a fictional story. It was a 45-second movie about a boy playing a joke on a gardener. The boy stepped on the hose when the gardener wanted to water his plants, then stepped off when the gardener inspected the nozzle, causing the water to spray him in the face. Mostly, though, the Lumière brothers filmed simple things from everyday life. They made movies of workers coming and going from their factory, soldiers marching in the street, people playing cards. It may not seem like the most exciting stuff today, but people back then were fascinated by the sheer novelty of seeing pictures that moved.

On January 25, 1896, the Lumière brothers had a screening of their newest movie. It was called L’Arrivée d’un Train en Gare de La Ciotat, (“Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station.”) The movie was only about 50 seconds long. All it showed was a group of people standing on a platform at the station waiting for a train, which could be seen in the distance. The movie had no sound, but as the train got closer and closer (and looked bigger and bigger!), the audience – who had all seen trains in real life – could imagine the noise and the power of the locomotive. Suddenly, people began to panic. They were convinced the train was going to crash into them and they ran, screaming, out of the theater.

It’s pretty hard to believe an image on a screen – even if it did appear to be speeding towards them – could cause such a commotion among so many people. The truth is, these days, many movie historians doubt this old story about the Lumière’s train is really true … and yet you don’t have to go all the way back to 1896 to find examples of movies that scare us.

In the summer of 1975, people weren’t swimming as much as usual. Attendance was down at beaches everywhere. Especially beaches on the ocean. People were afraid to go into the water. They were scared of being attacked by sharks.

The reason? A movie!

It was called Jaws and it became the first summer blockbuster.

SHORT SIDEBAR: BLOCKBUSTER DEFINED

The world “blockbuster” was first used in 1942 to describe very large, high explosive bombs during World War II. The word came to mean anything of great power or size, particularly a book or a movie that became hugely popular and made tons of money.

Jaws was based on a best-selling novel of the same name. It’s about a killer shark attacking victims near a popular beach during the height of summer vacation. It’s very scary, and sometimes pretty gross, with lots of blood and gore and chewed-up body parts. Some people consider Jaws a horror movie, although it’s really just a super-suspenseful adventure story. It did keep a lot of people out of the ocean that summer, but it sure didn’t keep them out of the theater! Jaws became the first movie to earn more than $100 million and it changed nearly everything about the way we go to the movies.

Before Jaws, summer was traditionally a slow time for theaters. It was largely when the major studios released movies they thought had little hope for success. Winter was for the big hits. Also, a new movie wasn’t released in a lot of theaters at the same time like it would be today. It opened on just a few screens in a few key cities. The hope was, fans and critics in those places would like a movie and word of its success would slowly build a bigger audience everywhere else. There was rarely any advertising for a new movie beyond the coming attractions trailers that played in theatres before other movies. Jaws was different. It had all sorts of advertising before it was released. Almost a year before the movie came out, the art for the poster was designed to look exactly like the cover of the new paperback edition of Jaws the book. As the opening date got closer, there were more commercials on TV for Jaws the movie than there had ever been for any other movie before. When it was finally released on June 20, 1975, Jaws opened all across North America on the same day, playing at 409 theaters in the United States and 53 more in Canada.

SHORT SIDEBAR: THE THEME FOR SCARY

The theme music from Jaws was pretty simple. It’s basically just two low notes repeated over and over. It starts out slowly, but gets faster and faster as the suspense builds. All these years later, the theme from Jaws is still the sound of approaching disaster. The music helped the movie create a fascination with sharks in our popular culture that continues right to this day.

Jaws was supposed to cost $4 million to make, but there were lots of problems. Filming key scenes out on the ocean made the movie look more authentic, but it was much harder than using a water tank inside a studio. There were also endless delays in constructing the three mechanical sharks director Steven Spielberg needed to use. (There was no such thing as computer-generated images in 1975.) By the time Jaws was completed, it wound up costing more than $9 million. That would be over $40 million today. On top of that, Universal Pictures spent $1.8 million to promote the movie. It was a huge amount of money to risk back then, but Jaws turned out to be worth every penny. The movie earned $7 million on its opening weekend and in just two weeks earned back all the money it cost to make it. Before the end of the summer, Jaws broke the all-time North American box office record of $84 million. By the end of the year, it earned more than $120 million.

Today, a blockbuster movie, filled with superheroes and special effects, might earn $120 million or more in a single weekend. Their fans might not know it, but they all owe a debt of thanks to Jaws and the summer of 1975. People would eventually go back in the water, but going to the movies would never be the same!

SIDEBAR: Movie Time

Imagine a movie so scary, it didn’t just keep people out of the water in the ocean – it kept them out of the water in their own bathrooms! Psycho was one of the most terrifying movies ever made. It was a horror story with a shocking murder in a shower. Like Jaws, Psycho had frightening theme music that still sounds scary today. Also like Jaws, Psycho changed the way people went to the movies.

When Psycho came out in 1960, most movies didn’t have set start times. They might play in a theater all day long and people would just come and go whenever they wanted. Missed the beginning? No problem! Stay in your seat when the movie ended and soon it would start up again. You didn’t even have to buy another ticket. When the movie got around to the part they had already seen, people would say, “this is where we came in.” They could leave, or, maybe, they’d stick around and watch it all over again. Director Alfred Hitchcock didn’t want people to do that for Psycho. The movie had a surprise ending, and Hitchcock wanted to protect that. So, each showing of Psycho had a set start time and no one was allowed into the theater after the movie began. Theater managers weren’t sure of this new policy, but Hitchcock insisted on it. Turned out, he was right. People were willing to stand in long lines to buy tickets and wait outside the theater until the movie started. Psycho became a huge success.

July 15, 2025

Have Cup, Will Travel

The Stanley Cup headed out on Sunday to begin its summer vacation with the players and staff of the 2024–25 champion Florida Panthers. The idea of giving everyone from the winning team their own day with the trophy began in 1993. To celebrate the Stanley Cup’s centennial that year, every member of the Montreal Canadiens was given his own day to spend with the trophy during the summer.

After the Stanley Cup got a rough ride with the New York Rangers in 1994 — it’s never truly been clear whether Ed Olczyk really fed the Kentucky Derby–winning racehorse Go for Gin from the Stanley Cup at Belmont Park —this popular practice was formalized in 1995. Since then, the Hockey Hall of Fame has provided the Cup with its own “keeper” to ensure things stay on schedule (the Cup travels nearly every day over the summer, and often goes overseas these days) and that things don’t get out of hand.

Ottawa won it in 1909, but a new Stanley Cup tradition would have to wait.

Ottawa won it in 1909, but a new Stanley Cup tradition would have to wait.Back in the old days — from the 1890s through the 1980s — the Stanley Cup champions were usually presented with the trophy shorty after winning it, either on the ice, in the dressing room afterwards, or at a banquet in a hotel or another civic location over the next week or two. In the early years, the Cup would often reside in the championship city for a while and go on display in some prominent public space. (My friend Stephen Smith wrote about this recently on his wonderful Puckstruck web site.) In more recent years, the players might get a few days to spend with the Cup, but then they weren’t likely to see it again until their team’s home opener at the start of the next season.

Before 1993, the Stanley Cup did occasionally make special appearances for personal reasons. I was recently reminded in a story from ESPN that in 1989, Phil Pritchard, the Cup’s most famous keeper (and, really, the only one back then), was persuaded by Colin Patterson of the Calgary Flames to bring the trophy to his home in the Toronto suburb of Rexdale. And in 1992, the Stanley Cup spent some time in the backyard of my longtime boss Dan Diamond of NHL Publishing.

Dan Diamond’s Stanley Cup commemorative book and his dog, Louis.

Dan Diamond’s Stanley Cup commemorative book and his dog, Louis.Dan’s day with the Stanley Cup came on July 5, 1992. (This was before my time with Dan Diamond & Associates.) The trophy had spent the previous day celebrating the 4th of July in Pittsburgh with Penguins captain Mario Lemieux and his teammates. (It may or may not have ended up in Mario’s swimming pool that time, as it when Pittsburgh first won it in 1991 and would again in 2009.) Dan picked up the Cup at Pearson Airport in Toronto in the morning and brought it to the McClelland & Stewart booth at the Canadian Booksellers Association Expo. M&S was getting in some early promotion for The Official National Hockey League Stanley Cup Centennial Book, which Dan was edited and they would publish the following summer. Guests at the booth could get their picture taken with the trophy that day.

Things being simpler then, Dan was told they didn’t need the Stanley Cup returned to the Hockey Hall of Fame until the next morning. So he brought it home for a backyard barbecue. There were about 35 friends on hand who were pretty excited to see it … although Dan’s collie, Louis (pronounced Louie), reclining with the Cup on the table behind him in the photograph above, seems a little more chill.

But is it possible that special days with the Stanley Cup began all the way back in 1909 with hockey legend Cyclone Taylor?

From Stanley Cup: 120 Years of Hockey Supremacy and

From Stanley Cup: 120 Years of Hockey Supremacy andfrom Star Power: The Legend and Lore of Cyclone Taylor.

After the Ottawa Senators clinched the Stanley Cup with an 8–3 win over the Montreal Wanderers on March 4, 1909, the team was rewarded with a banquet at the new Russell House hotel in the Canadian Capital on March 16. Reporting on the evening the next day, The Ottawa Citizen noted: “Fred Taylor made the unusual request that he be allowed to take the Stanley Cup home to Listowel with him at Easter time. He said it had always been his highest ambition to figure on a Stanley Cup team and now that he had assisted in winning it he wanted to take the celebrated trophy home to his native town to let the Listowel people get a look at it. Taylor guaranteed to return the Cup in perfect order and his wish may be granted, providing the trustees don’t object.”

The Citizen never followed up on the story. Nor did The Ottawa Journal. (Two newspapers that are now easily searchable online.) But at some point, I came across a story somewhere that said Cyclone Taylor wasn’t allowed to bring the Stanley Cup home to Listowel. I wrote as much in a children’s biography of Taylor in 2007 and in a book about the Stanley Cup in 2012. But, in 2021, when Stephen Smith asked me about the Taylor incident for a story he was writing for his web site, I could NOT come across what I’d found. I can no longer remember if it was in a newspaper or a book (there’s nothing in Eric Whitehead’s biography of Taylor), but I was stunned when I couldn’t find anything in my notes.

I’m still positive I’d found something … but it bothered me that I didn’t have proof.

Until a few days ago!

Another colleague, Greg Nesteroff (a British Columbia writer and historian who maintains a fascinating website about Frank and Lester Patrick), told me The Ottawa Free Press had been digitized by a British newspaper web site. I knew I hadn’t found my Cyclone story there originally, but I still felt certain The Free Press would have something about it. And with Greg’s help, I found what I was looking for!

There were actually two stories. The one shown above is from April 10, 1909, and it more or less says the trustees hadn’t allowed Taylor to bring the trophy home. The second story, from April 27, offers as the excuse that the Stanley Cup was too big to travel and that the freight charges “would be considerable.”

As noted in the book excerpts above, Fred W. (Cyclone) Taylor

As noted in the book excerpts above, Fred W. (Cyclone) Taylor engaged in a little freelance engraving back in 1909.

The way the second story is written, the exaggerated size of the Stanley Cup at that time is either meant as a joke … or it’s a big city Ottawa reporter mocking the citizens of small town Listowel.

There’s no way to know for sure, but I’m glad to have proof again that I was right!

******************************************************************************************

Sad news yesterday for Blue Jays fans old enough to remember Jim Clancy, who passed away at the age of 69. Clancy was a workhorse pitcher back in the days when that meant something. Only one other pitcher since then (Charlie Hough in 1987) has matched the 40 games Clancy started for Toronto in 1982. He was a Blue Jay from 1977 to 1988, so covering all five years of my time with the ground crew from 1981 to 1985. My favorite Clancy memory is from his 40th and final start in 1982.

The Jays finished that season strong, and on October 3, 1982, Jim Clancy capped the year with a complete game five-hitter in a 5-2 win over Seattle. With that, the Jays finished the season with a record of 78-84. Not very impressive, you might think, but for the first time ever Toronto wasn’t buried in last place. True enough, they were tied with Cleveland for sixth instead of alone in seventh, but the 19,064 on hand roared their approval as Clancy came off the mound and fired his cap and glove into the stands. “We’re Number 6!” some people shouted, and “Bring on the Indians!” You just knew better things were ahead! And indeed the next 10 years would culminate in back-to-back World Series championships.

Those were the Jays!

June 19, 2025

Edmonton Circa 1908

Well, Edmonton might have the best players, but the defending champions clearly have the better team. (And there’s nothing wrong with their top stars either!) So, the Stanley Cup will remain where it’s been for a while longer. It’s a fairly apt description of the series that wrapped up with a Florida Panthers victory on Tuesday night, but it would also apply to the Oilers’ first shot at the Stanley Cup, with Wayne Gretzky and company, against the New York Islanders back in 1983. As it turns out, it’s also a pretty good account of Edmonton’s very first attempt to win the Stanley Cup … all the way back in 1908!

The history of hockey in Edmonton dates to 1894, which is a year after the Stanley Cup was first presented in 1893. Early Edmonton hockey teams were amateur clubs — as all sports organizations in Canada were — but shortly after the first openly professional hockey teams and leagues started up in Canada in the winter of 1906–07, an Edmonton team decided to go pro. Fred Whitcroft was imported from Peterborough to star on and manage the Edmonton pros.

A collectible postcard of Fred Whitcroft with the Kenora Thistles and a newspaper headline from The Winnipeg Tribune on December 18, 1908 when the Edmonton team stopped over in the city en route to Montreal.

A collectible postcard of Fred Whitcroft with the Kenora Thistles and a newspaper headline from The Winnipeg Tribune on December 18, 1908 when the Edmonton team stopped over in the city en route to Montreal.The early Edmonton teams had been known as the Thistles, but was often just called the Edmonton Hockey Club. The web site for the Society for International Hockey Research calls the team the Edmonton Capitals starting in 1907–08, but the team was often called the Edmonton Seniors, the Edmonton Professionals or just the Edmontons. A story in The Edmonton Evening Journal on December 28, 1908 — on the night Edmonton’s first Stanley Cup challenge began — says Fred Whitcroft called his team “the Little Tigers, partly because of their vivid orange and black stripes and partly because of the ferocity which he imagines them to be capable of.”

Fred Whitcroft first came to attention in hockey playing in Peterborough, Ontario, where he grew up. He had joined the Kenora Thistles midway through the 1906–07 season when they ran into injury problems. Whitcroft helped them hold on to the championship in the Manitoba Hockey League, but the Thistles lost a Stanley Cup rematch to the Montreal Wanderers at the end of the season. Whitcroft went home to Peterborough, and though various newspapers in the spring of 1907 said he would return to Kenora, on October 14, 1907, The Edmonton Bulletin reported that Whitcroft “has wired from Peterborough the acceptance of the position offered him by the local club.” He left Peterborough by train on Friday, October 18 and arrived in Edmonton late at night on Tuesday the 22nd.

From The Edmonton Evening Journal, March 24, 1908. The players are: Bill Banford and Bill Crowley (standing) Hay Miller, Fred Whitcroft, Harold Deeton and Bert Boulton (middle) and Walter “Shorty” Campbell, Allan Parr and Bob Holley (front).

From The Edmonton Evening Journal, March 24, 1908. The players are: Bill Banford and Bill Crowley (standing) Hay Miller, Fred Whitcroft, Harold Deeton and Bert Boulton (middle) and Walter “Shorty” Campbell, Allan Parr and Bob Holley (front).The team Fred Whitcroft helped put together in Edmonton for the 1907–08 season was a good one. According to The Edmonton Evening Journal, recapping the season in its March 24, 1908 edition, the team won 19 of 22 league games playing against teams from nearby Strathcona and North Battleford, Saskatchewan. They also played and won five exhibition games. (They may actually have played 22 games in total.) The Journal reported that Whitcroft “carries off the honours for the season’s play,” scoring 49 goals in 16 games. Among his teammates, only Harold Deeton (25 goals in 16 games) and Hay Miller (21 in 15) came close.

As champions of the Interprovincial Professional Hockey League of Alberta and Saskatchewan, Edmonton challenged the defending Stanley Cup champion Montreal Wanderers in March of 1907. A two-game, total-goals series was arranged for December 28–30, 1908 before the start of the next season. The trustees in charge of the Stanley Cup had recently passed new rules hoping to bar challenging teams from recruiting star players as “ringers” for the big games. Still, when a challenge from one season was held over to the next, the trustees knew it was impossible to force teams to re-sign all their players to play with them again. Edmonton was told that as long as any new players were under contract before the start of the new season, they would be allowed to play with them for the Stanley Cup. The only proviso was that they couldn’t sign anyone who’d played for the Cup during the 1907–08 season.

Tommy Phillips and Lester Patrick.

Tommy Phillips and Lester Patrick.Fred Whitcroft was apparently a whiz as a story teller and very popular among his fellow players. That couldn’t have hurt when he set out from Edmonton in the fall of 1908 to sign up new players to bolster his team. Tommy Phillips (who would soon sign with Edmonton) had been the one who brought “Whitty” to Kenora in 1907. In speaking with The Vancouver Province on November 28, 1908, Phillips said: “Fred has this fellow Munchausen lashed to the third rail. He told us more hair-raising experiences than would fill a twenty-volume encyclopedia… Fred was a dandy to make the time fly on long trips.”

After speaking with Whitcroft following the 1909–10 hockey season, a reporter from The Ottawa Citizen in a story on March 24, 1910, said “Whitcroft … is recognized as the champion storyteller of the National Hockey Association. ‘Whitty’ will take you on a flying trip to the North Pole just as readily as he will tell you how he floated across the Rockies in an airship to sign on Lester Patrick for the Edmonton club.” Whitcroft did sign Lester Patrick for the 1908 Stanley Cup series, but there’s no record of him flying out to Nelson, British Columbia to negotiate with him — and you’d think something like that would have made the papers!

Didier Pitre and Joe Hall.

Didier Pitre and Joe Hall.Whitcroft, Tommy Phillips and Lester Patrick were all future Hockey Hall of Famers. Whitcroft signed another one for Edmonton in Didier Pitre. He apparently made an offer to Cyclone Taylor too, but Taylor either turned him down or the stories aren’t true. Whitcroft also signed Joe Hall, who scored eight goals in the one exhibition game he played in Edmonton but this future Hall of Famer was released shortly thereafter. In the December 28, 1908, Edmonton Journal story, it was reported that other Western papers said Whitty released Hall out of fear the notorious Bad Man would “rough it up and cause trouble in the East,” but Whitcroft said Hall was let go “because he was not playing the game.” Three other players signed for Edmonton’s Stanley Cup challenge were Hal McNamara, a long time pro of this era, Steve Vair, who was a solid player at the time, though little-known today, and goalie Bert Lindsay. Lindsay also had a long professional career but is best remembered as the father of Detroit Red Wings legend Ted Lindsay.

The Edmonton team began practice for the new season on November 25, 1908. They would play three exhibition games in Edmonton before departing for Montreal on December 16. But with new players constantly arriving, they never had their full lineup together before a workout or two in Montreal. For Game One against the Wanderers, Edmonton lined up with Steve Vair at center and Tommy Phillips and Hal McNamara on the wings. Fred Whitcroft was the rover with Lester Patrick and Didier Pitre at point and cover-point (defense) in front of Bert Lindsay. Only Whitcroft had played in Edmonton the previous season. The Wanderers had Harry Smith at center with future Hall of Famers Moose Johnson and Jimmy Gardner on the wing. Pud Glass was the rover with Walter Smaill at cover point. Two more future Hall of Famers in Art Ross (point) and Riley Hern (goal) completed the lineup.

Bert Lindsay and Steve Vair.

Bert Lindsay and Steve Vair.At the end of the first half (hockey was played in two 30-minute halves not three 20-minute periods until 1910–11), Edmonton led 3–2. “We thought we were going some in the first half,” Whitcroft was quoted as saying in The Montreal Star the next day, “only to find out we were not in the second half.” The Wanderers scored five times for a 7–3 victory.

Newspapers the next day reported Tommy Phillips had broken his ankle with about 10 minutes to go, but continued to play until the end. Phillips himself would later say he’d actually broken his ankle shortly after scoring to give Edmonton a 2–1 lead midway through the first half and played the final 45 minutes despite his injury.

With Phillips out, Whitcroft was forced to shake up his all-star team. He dropped Steve Vair back to rover, benched Hal McNamara and put on an all-Edmonton forward line of himself, Harold Deeton and Hay Miller. Their familiarity with each other made a big difference, with Whitcroft scoring once and Miller (two goals on the game) and Deeton (three) scoring in the final minutes for a 7–6 victory.

Still, the Wanderers won the total-goal series with a 13–10 victory. The champions for most of the last two years retained the Stanley Cup. The challengers would have to try again.

May 30, 2025

Stanley Cup Rematches

Personally, I’m not a big fan of the Florida Panthers, but I’ve got to give them their due. Three straight trips to the Stanley Cup Final and a shot at their second straight championship is pretty impressive. The Tampa Bay Lightning made three straight appearances in 2020, 2021 and 2022 and won the first two. Still, I wonder if history will look back at these teams some day as among the great champions in hockey?

Regardless of history, I’ll be cheering for the Edmonton Oilers. (Though I have my doubts about their chances. It’ll be odd if Toronto ends up giving Florida their biggest challenge!) It’s been rare in the Stanley Cup annals for the same two teams to meet for the Cup in two straight years as is about to happen.

It’ll be Connor McDavid and the Edmonton Oilers versus Aleksander

It’ll be Connor McDavid and the Edmonton Oilers versus Aleksander Barkov and the Florida Panthers for the Stanley Cup again this year.

So, will the champion Panthers make it two in a row?

Or will the “challenger” Oilers win this year?

Let’s see what history has to say…

The first rematch for the Stanley Cup actually occurred in the same calendar year … back in 1896 when the Cup really was a challenge trophy. This was just the fourth season in Stanley Cup history and the year it became a national passion in Canada.

On February 14, 1896 the Winnipeg Victorias faced the defending champion Montreal Victorias in a one-game challenge for the championship. After they scored a 2–0 victory and brought the trophy back with them to the capital of Manitoba, it was cause for a great celebration. Certainly much bigger than what had been seen in Montreal when teams from there won the trophy in 1893, 1894 and 1895.

Dan Bain of the Winnipeg Victorias and Mike Grant of the Montreal Victorias.

Dan Bain of the Winnipeg Victorias and Mike Grant of the Montreal Victorias.After both teams retained the championships of their respective leagues, the Victorias of Montreal challenged their Winnipeg counterparts to a rematch on the eve of the next season. In the lead-up to the game, the pursuit of the the Stanley Cup made news all across the country. The Montreal Victorias scored a 6–5 victory on December 30, 1896 and would retain the Cup until 1899.

REMATCH SCORE: 1–0 for the challengers

The Winnipeg Victorias won the Stanley Cup again in a challenge victory over the Montreal Shamrocks in 1901. In January of 1902 they successfully defended the championship over the Toronto Wellingtons, but in March they were defeated by the Montreal Hockey Club (aka, the Montreal AAA or Amateur Athletic Association.) Again, both teams retained the championship of their respective leagues and Winnipeg challenged Montreal to a rematch. The series was played at the end of January and beginning of February in 1903 and Montreal won again to retain the Stanley Cup.

REMATCH SCORE: 1–1 challengers and champions

The Ottawa Silver Seven (officially the Ottawa Hockey Club) won the Stanley Cup at the end of the 1902–03 season and held it until being defeated by the Montreal Wanderers at the end of the 1905–06 season. Among their many successful title defenses, Ottawa had defeated the Rat Portage Thistles in 1903 and 1905. Under the town’s new name, the Kenora Thistles defeated the Wanderers in January of 1907 in a challenge carried over from the previous year. After both teams successfully defending their own league championships, the Thistles and Wanderers met again in March for the Stanley Cup and this time the Wanderers came out on top.

Billy McGimsie of the Kenora Thistles and Ernie Russell of the Montreal Wanderers.

Billy McGimsie of the Kenora Thistles and Ernie Russell of the Montreal Wanderers.REMATCH SCORE: 2–1 for the challengers

There would be no more back-to-back Stanley Cup rematches until after the NHL came on the scene for the 1917–18 season and then became the only league to compete for the trophy starting in 1926–27. In the spring of 1932, Toronto won the Stanley Cup for the first time under the Maple Leafs name with a three-game sweep of the New York Rangers in the best-of-five series. A year later, the Rangers got revenge with a victory in four games.

Busher Jackson of the Maple Leafs and Frank Boucher of the Rangers.

Busher Jackson of the Maple Leafs and Frank Boucher of the Rangers.REMATCH SCORE 3–1 for the “challengers”

The Maple Leafs would be involved in the next rematch too. After an upset over the Montreal Canadiens in a six-game series in 1947, Toronto defeated Detroit in a four-game Stanley Cup sweep in 1948. A year later, it was the Leafs and Red Wings again with Toronto scoring another sweep and becoming the first team in NHL history to win the Cup three years in a row.

Toronto’s Teeder Kennedy and Detroit’s Sid Abel.

Toronto’s Teeder Kennedy and Detroit’s Sid Abel.REMATCH SCORE: 3–2 for the “challengers”

And speaking of threes, the only time in NHL history that the same teams have met in the Stanley Cup Final three years in a row occurred from 1954 through 1956. The Red Wings defeated the Canadiens in 1954 and 1955, winning in seven games each year. But in 1956, Montreal downed Detroit in five games to launch the greatest dynasty in NHL history with the first of five consecutive Stanley Cup championships. During that dynasty, the Canadiens defeated the Boston Bruins in both 1957 and 1958 and the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1959 and 1960.

Gordie Howe and Maurice Richard.

Gordie Howe and Maurice Richard.REMATCH SCORE: 5–4 for the champions

After the Maple Leafs won the Stanley Cup in 1951, they wouldn’t win again until 1962. Believe it or not, as we’re now at 58 years without a championship in Toronto, that 11-year drought was once the longest in Maple Leafs history! Toronto defeated the Chicago Black Hawks to win the Stanley Cup in 1962, and then beat the Detroit Red Wings two years in a row in 1963 and 1964. The Leafs would win again (defeating the Canadiens) in 1967 … but Toronto is still waiting for the next Stanley Cup victory.

Johnny Bower and Terry Sawchuk faced each other

Johnny Bower and Terry Sawchuk faced each other in 1963 and 1964 but were teammates in 1967.

REMATCH SCORE: 6–4 for the champions

After Montreal lost to Toronto in 1967, the NHL added six new expansion teams. The rules of the day established a playoff format that guaranteed a new team would reach the Stanley Cup Final for the next three seasons. In 1968, the Canadiens swept the St. Louis Blues and then did so again in 1969. (St. Louis was swept by the Boston Bruins in 1970, making them and the Toronto Maple Leafs of 1938-to-1940 the only NHL teams to lose the Stanley Cup Final in three straight seasons.)

Jean Beliveau had won the Conn Smythe trophy as playoff MVP the first

Jean Beliveau had won the Conn Smythe trophy as playoff MVP the first time it was presented in 1965. Glenn Hall won it in a losing cause in 1968.

REMATCH SCORE: 7–4 for the champions

The Montreal Canadiens of the late 1970s were arguably the most dominant team in NHL history. After ending the Philadelphia Flyers’ reign (of terror) as two-time champions by sweeping them 1976, the Canadiens swept the Boston Bruins in 1977 and beat them in six in 1978 en route to four straight Stanley Cup titles.

The Bruins nearly beat the Canadiens in the 1979 playoff semifinals but a

The Bruins nearly beat the Canadiens in the 1979 playoff semifinals but a late goal from Guy Lafleur in Game Seven was key to a comeback victory.

REMATCH SCORE: 8–4 for the champions

Hot on the heels of the Canadiens 1970s dynasty came the 1980s New York Islanders. Entering the NHL as the worst expansion team to that point in history in 1972–73, the Islanders quickly became a powerhouse but could never get it done in the playoffs. Until they did. The Islanders defeated the Philadelphia Flyers for the Stanley Cup in 1980, the Minnesota North Stars in 1981, the Vancouver Canucks in 1982 and then the Edmonton Oilers for four in a row in 1983. Wayne Gretzky and others would say losing to the Islanders showed them just how much dedication it would take to win the Stanley Cup. In 1984 the two teams were back in the Final, and after the Islanders had won a record 19 straight playoff series over five seasons the Oilers ended their reign and launched their own dynasty.

Stamps honouring Mike Bossy of the Islanders and Edmonton’s Wayne Gretzky.

Stamps honouring Mike Bossy of the Islanders and Edmonton’s Wayne Gretzky.REMATCH SCORE: 8–5 for the champions

No two teams met again in a Stanley Cup rematch until the Detroit Red Wings and Pittsburgh Penguins in 2008 and 2009. The Red Wings — who had gone from 1954 through 1996 without winning a championship — won their fourth title since 1997 when they downed a young Sidney Crosby and the Penguins in six games in 2008. Both teams were back a year later, and this time it was Pittsburgh who came out on top. The Penguins were 2–1 winners in Games Six and Seven, with goalie Marc-Andre Fleury making a diving stop off Nicklas Lidstrom with two seconds remaining to preserve the Stanley Cup victory.

Nicklas Lidstrom of Detroit and Sidney Crosby of Pittsburgh.

Nicklas Lidstrom of Detroit and Sidney Crosby of Pittsburgh.REMATCH SCORE: 8–6 for the champions

So, it would seem the Panthers have the better odds of winning again than the Oilers do of winning this rematch. Although the 1984 Oilers did pull it off, and the “challengers” have won the last two times this has happened. But it’s hard to prove there’s any mathematical correlation, and even if there is there’s probably not enough evidence to reach any conclusions. So even though it gets harder and harder to stay inside and watch hockey when (if!) the weather finally heats up in June and you don’t really have a team in it, I guess we’ll just have to watch and see what happens.

April 17, 2025

Early Skirmishes in the Battle of Ontario

The NHL season wraps up tonight, but we already know all the playoff pairings, including Toronto versus Ottawa. It’s the first Battle of Ontario since the two teams met four times in five years from 2000 to 2004. (It’s hard to believe it’s been 21 years since then!) The Maple Leafs have won the Atlantic Division, giving them their first division title in a full (non-Covid) season since 1999–2000. The Senators earned the first wild card spot in the Eastern Conference and are back in the playoffs for the first time since the 2016–17 season. The Senators won all three games against the Maple Leafs during the regular season, but Toronto should be good enough to win this. Then again, there have been so many playoff disappointments in the Auston Matthews–Mitch Marner–William Nylander–John Tavares “Core-4” era that it’s impossible to be too confidence.

Still, as I often say, people shouldn’t come to me for advice or opinions on current hockey because I can always tell you more about who won the Stanley Cup (and how) 100 years ago than I can tell you who’s going to win it now. So, with that in mind, we’re going back to the early 1920s for the first Toronto–Ottawa NHL playoffs match-ups.

Babe Dye of Toronto and Punch Broadbent of Ottawa.

Babe Dye of Toronto and Punch Broadbent of Ottawa.The Senators won their first Stanley Cup since the formation of the NHL at the end of the third season in 1920. Then, led by such stars as Frank Nighbor, Punch Broadbent and Cy Denneny at forward, Eddie Gerard and George Boucher on defence, and Clint Benedict in goal, Ottawa roared out to an 8–2–0 start to the 1920–21 season. That earned them first place in the first-half standings of the four-team NHL and clinched a spot in the postseason. The Toronto St. Patricks won the second half of the schedule with a record of 10–4–0 and faced the Senators in the playoffs for the NHL championship.

Toronto had come on strong in the second half of the season, boosted by the mid-season addition of former Ottawa star Sprague Cleghorn. Offensively, the team was led by Babe Dye who topped the NHL with 35 goals during the full 24-game schedule. Ottawa had fallen to a 6–8–0 record during the second half and Toronto fans were optimistic, but the Senators shutout the St. Pats 5–0 on home ice in the first game of their total-goal playoffs, and then won the second game 2–0 in Toronto to take the series 7–0. The Senators then defeated the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association to win the Stanley Cup again.

The Ottawa Journal, March 9, 1922

The Ottawa Journal, March 9, 1922The NHL abandoned the split schedule in 1921–22, deciding instead that the first- and second-place teams at the end of a full schedule would meet in the playoffs for the league championship. Ottawa was 14–4–2 through 20 games, but then lost four in a row to finish 14–8–2. Punch Broadbent led the NHL with 31 goals and 45 points on the season, but it was Clint Benedict and the Senators’ league-best team defense that had them on top. In Toronto, Babe Dye tied Broadbent with 31 goals and Harry Cameron led the league with 17 assists, but neither the team’s offense nor its defense was as good as Ottawa’s. The St. Patricks needed three wins in their last four games to finish 13–10–1 and stave off Montreal (12–11–1) for second place and get another chance at the Senators in the playoffs.

“Tomorrow night at the Arena the two best professional teams in eastern Canada will cross sticks, when the St. Patrick’s and Ottawa play the first game of the National Hockey League play-off series,” reported Toronto’s Globe newspaper on March 10, 1922. “The Senators have been the ‘top-dogs’ in the pro league for two years, and they are ambitious to make it three titles in a row, and so take their place in history with the famous Ottawa Silver Seven, which in other years won the Stanley Cup for the Capital.”

Both teams professed their confidence before the March 11 opener. Toronto hoped to build up a lead on home ice in the first game of the two-game, total-goals series. And with warm weather predicted in Ottawa for the second game two nights later, the Senators also hope to take a lead on the artificial ice in Toronto because it was thought the St. Pats would have an advantage on the soft, natural ice in the Canadian capital.

Toronto Star headlines, March 13 and 14, 1922.

Toronto Star headlines, March 13 and 14, 1922.Toronto scored two quick goals for an early lead in Game 1, but Ottawa rebounded for a 3–2 lead at the end of one period. It was 4–3 Ottawa late in the second, but Toronto tied it when Babe Dye took a pass from Harry Cameron and scored just before the period ended. A disputed goal by Corb Denneny (brother of Ottawa’s Cy) late in the third period gave Toronto a 5–4 win and a one-goal lead in the series.

“The most prolific source of hockey conversation to-day,” reported The Toronto Daily Star on March 13, “is the disputed goal in Saturday night’s pro game between Ottawa and St. Patricks. ‘Jimmy’ Main, the well-known Toronto Canoe Club member, who parks himself right beside the goal umpire’s cage for every big game, says that the puck was six inches over the line. He says Goalkeeper Benedict stopped the original shot and then as he fell down the puck slid out about two feet. Corbett Denneny took a sweeping poke at it with his stick and reached it. The puck circled in over the line and was hooked out by Eddie Gerard. Main says that the reason Benedict got so sore was that he knew he had stopped the original shot and that he knew nothing about Denneny’s poke at the rebound. He saw the puck outside [the net] and figured it had always remained there.”

The second game of the series in Ottawa was played on soft, slushy ice as expected. The Senators had the best of the play, and outshot the St. Pats badly, but they couldn’t put one past Toronto goalie John Ross Roach. The St. Pats spent much of the game firing the puck out of their end and all the way down the ice, which was not punished with an own-zone face-off for icing in this era. The game ended in a scoreless tie, which gave Toronto the NHL championship by a total score of 5–4.

Headline in The Globe, March 15, 1922.

Headline in The Globe, March 15, 1922.When the St. Pats got back to Toronto the day after the game (March 14), they were welcomed by supporters who met their train at Union Station. When they got to their dressing room at the Arena Gardens on Mutual Street, they found a wreath-strewn coffin said to contain the last remains of the Ottawa team. “Bottles … were used as candle-holders, while the Arena attendants played the Dead March in ‘Saul’,” reported The Globe of March 15. “Long green streamers were used to decorate the interior of the room, and all in all, a striking picture was presented… [T]here were other features which amazed the many visitors who flocked to the dressing room when they heard that the last rites were being performed at the expense of the Ottawa team.”

The NHL championship gave Toronto the right to face the PCHA champions from Vancouver for the Stanley Cup. The St. Patricks beat the Millionaires three game to two in the best-of-five series. But unlike 1922, it’ll take more than just a win and a tie to defeat the Senators this year, and then three more rounds — not five more games — to win the Stanley Cup. Still, Leafs fans are hopeful!

April 2, 2025

The All-Time List of All-Time Leaders…

Whether he does it before the end of this season (which he could) or not until the start of next year, Alex Ovechkin will very soon pass Wayne Gretzky as the leading goal-scorer in NHL history. Like so many of the records Gretzky set, this one seemed like it would never be broken. We’ll try to avoid any politics here, so let’s not think about Gretzky being a friend of Donald Trump and Ovechkin of Vladimir Putin. We don’t get to pick our moments, and the breaking of the all-time NHL record for goals is too momentous for someone who calls himself a hockey historian to ignore. So please read on for an all-time account of the NHL’s all-time leading goal-scorers…

The first NHL games were played on December 19, 1917. The Montreal Wanderers hosted the Toronto Arenas and beat them 10–9. The Montreal Canadiens were in Ottawa and beat the Senators 7–4. The Canadiens game in Ottawa was scheduled to start at 8:30 that night but was delayed for about 15 minutes. The Wanderers and Arenas faced off in Montreal at 8:15, officially making it the NHL’s first game. Dave Ritchie of the Wanderers scored just one minute into the first period against Toronto, giving him the honor of scoring the first goal in NHL history. But Ritchie wouldn’t remain the career scoring leader for long.

Two players scored five goals apiece on the first night in NHL history: Harry Hyland of the Wanderers and Joe Malone of the Canadiens. Hyland quickly fell off Malone’s pace, but Cy Denneny of Ottawa, who scored three in a losing cause on opening night, kept up. In fact, by the fourth game for each player, played on December 29, 1917, Denneny moved atop the leader board with 12 goals to Malone’s 11. Denneny reached 13 through five games on January 2, 1918. Malone scored twice in his fifth game on January 5 to reach 13 as well, but Denneny scored twice that night in his sixth game to hit 15. Malone moved back on top on January 12 when he scored five again to reach 20 on the season in just his seventh game played.

Joe Malone and Cy Denneny.

Joe Malone and Cy Denneny.Joe Malone ended the NHL’s first season of 1917–18 with a league-leading 44 goals in 20 games played which (of course!) gave him the all-time league lead at the time. Malone played just eight games in 1918–19 and scored seven goals. Cy Denneny, who was second in the NHL with 36 goals in the first season, equalled Malone as the all-time leader when both scored their 45th career goals on January 4, 1919 and Denneny surpassed Malone with three goals on January 9 to give him 48. Denneny finished the 1918–19 season as the NHL’s career leader with 54 goals to Malone’s 51

Joe Malone moved to the top of the leaderboard again during the 1919–20 season. Playing with the Quebec Bulldogs, Malone matched Denneny with 55 career goals on January 1, 1920 and moved ahead — where he would remain for the rest of his career — when he scored four in his next game on January 7. Malone would lead the NHL again that season with 39 goals, which gave him 90 in his career.

100 CAREER GOALS

Joe Malone, Hamilton Tigers. February 5, 1921 vs Clint Benedict, Ottawa Senators.

(Milestone goal was Malone’s second of two in a 7–3 loss.)

Joe Malone’s final goal — his only goal of the 1922–23 season (he scored no goal in 10 games in 1923–24) — came on February 3, 1923, in the Montreal Canadiens’ 4–1 win over the Ottawa Senators. He finished his NHL career with 143 goals in 126 games. Cy Denneny of the Ottawa Senators moved ahead of Malone atop the NHL career list again just two weeks later, scoring his 144th on February 17, 1923, versus the Hamilton Tigers’ Jake Forbes.

After passing Cy Denneny to take back the NHL career lead in goals, Joe Malone remained the leader for just over three years / 1,137 days (January 7, 1920 – February 17, 1923) until Denneny passed him again as the overall leader.

200 CAREER GOALS

Cy Denneny, Ottawa Senators. March 4, 1925 vs Clint Benedict, Montreal Maroons.

(Milestone goal was Denneny’s only goal of the game in a 5–1 victory.)

Howie Morenz and Nels Stewart.

Howie Morenz and Nels Stewart.Cy Denneny scored his 247th and final goal on December 4, 1928, as a member of the Boston Bruins against the New York Rangers’ John Ross Roach. In all, he scored 247 goals in 329 NHL games. Howie Morenz surpassed Denneny for the NHL career lead with his 248th goal on December 23, 1933, also against Roach, who was then with the Detroit Red Wings.

After Cy Denneny surpassed Joe Malone as the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL’s leader for 10+ years / 3,962 days (February 17, 1923 – December 23, 1933) until being surpassed by Howie Morenz.

Howie Morenz scored his 271st and final goal on January 24, 1937, versus the Chicago Black Hawks’ Mike Karakas. Morenz suffered a career-ending broken leg two games later on January 28, 1937 (he’d played 550 games) and would die of complications while still in hospital on March 8, 1937. By the time of his death, Morenz had already been surpassed as the NHL’s career goal-scoring leader by Nels Stewart of the New York Americans. Stewart scored his 272nd goal on February 16, 1937, against the Montreal Canadiens’ Wilf Cude.

After Morenz became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for three+ years / 1,151 days (December 23, 1933 – February 16, 1937) until being passed by Nels Stewart.

300 CAREER GOALS

Nels Stewart, New York Americans. March 6, 1938 vs Dave Kerr, New York Rangers.

(Milestone goal was Stewart’s only goal of the game in a 3–1 victory.)

Nels Stewart scored his 324th and final goal with the New York Americans on March 16, 1940, versus the Toronto Maple Leafs’ Turk Broda. He ended his NHL career with 650 games played. Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens surpassed Stewart with his 325th goal on November 8, 1952, versus the Chicago Black Hawks’ Al Rollins. Richard had scored his first career goal, in his second NHL game, exactly 10 years earlier. That goal had come unassisted against Steve Buzinski of the New York Rangers at 9:11 of the second period in a 10–4 Montreal victory.

After Nels Stewart became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 15+ years / 5,744 days (February 16, 1937 – November 8, 1952) until his mark was beaten by Maurice Richard.

Maurice Richard and Gordie Howe.

Maurice Richard and Gordie Howe.400 CAREER GOALS

Maurice Richard, Montreal Canadiens. December 18, 1954 vs Al Rollins, Chicago Black Hawks.

(Milestone goal was Richard’s only goal of the game in a 4–2 victory.)

500 CAREER GOALS

Maurice Richard, Montreal Canadiens. October 19, 1957 vs Glenn Hall, Chicago Black Hawks.

(Milestone goal was Richard’s only goal of the game in a 3–1 victory.)

Maurice Richard scored his 544th and final goal on March 20, 1960, also against Al Rollins, who was then with the New York Rangers. He played 978 games in his career. Gordie Howe of the Detroit Red Wings moved past Richard with his 545th goal on November 10, 1963, versus the Montreal Canadiens’ Charlie Hodge.

After Maurice Richard became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 11 years / 4,019 days (November 8, 1952 – November 10, 1963) until he was passed by Gordie Howe.

600 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings. November 27, 1965 vs Gump Worsley, Montreal Canadiens.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only of the game in a 3–2 loss.)

700 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings. December 4, 1968 vs Les Binkley, Pittsburgh Penguins.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only goal of the game in a 7–2 victory.)

Gordie Howe retired from the NHL after his 25th season in 1970–71 with 786 goals. At the time, Bobby Hull was a distant second on the career list with 554. Howe would return to action in the World Hockey Association in 1973–74. In his six seasons in the WHA, Howe had 174 goals and 334 assists for 508 points in 419 regular-season games. He returned to the NHL in 1979–80 at the age of 51, playing a full 80-game schedule with the Hartford Whalers.

800 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Hartford Whalers. February 29, 1980 vs Mike Luit, St. Louis Blues.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only goal of the game in a 3–0 victory.)

Wayne Gretzky and Alex Ovechkin.

Wayne Gretzky and Alex Ovechkin.In his final NHL season in 1979–80, Gordie Howe had 15 goals and 26 assists to bump his career goals total to 801. Howe scored his 801st and final goal in his last regular-season game (1,767 games) on April 6, 1980, against the Detroit Red Wings’ Rogie Vachon. He would remain the all-time leader until Wayne Gretzky scored his 802nd goal on March 23, 1994, for the Los Angeles Kings versus the Vancouver Canucks’ Kirk McLean. The Kings lost 6–3.

After Gordie Howe became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 30+ years / 11,091 days (November 10, 1963 – March 23, 1994) until his mark was surpassed by Wayne Gretzky.

Wayne Gretzky scored his 894th and final goal on March 29, 1999, against the New York Islanders’ Wade Flaherty. He played 1,487 games in his career. As of this post on April 2, 2025, Gretzky still holds the record with Alex Ovechkin of the Washington Capitals closing in. Ovechkin has 891 goals in 1,484 career games with eight games to go in 2024–25. If he hadn’t missed 16 games earlier this season with a fracture fibula, Ovechkin might already have caught Gretzky. His final game of the regular season comes against Sidney Crosby and the Pittsburgh Penguins on April 17.

Since Wayne Gretzky became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he has remained the NHL leader for 31 years / 11,333 days (March 23, 1994 – April 2, 2025).

February 25, 2025

Best on (200 or 300th) Best: Part II

Well, you couldn’t have asked for a much better Final from the 4 Nations Face-Off last week. Especially from a Canadian perspective! Fast, and aggressive, but without any goon stuff. And the best player in the world scored the winning goal. But now, we’ll return to 1949 when things didn’t end up quite so well for Canada. Last week’s post ended with Canada’s 47–0 win over Denmark at the 1949 World Championship, and today, we continue with the rest of that tournament and the conclusion of the Sudbury Wolves/Canadian team’s three-plus month tour of Europe…

A day after that February 12 win over Denmark, Canada beat Austria 7–0 to win Group A and advance to the six-team Medal Round. (The Austrians would beat Denmark 25–1 on February 14 and also advanced). The USA (3–0–0) and Switerzland (2–1–0) advanced from four-team Group B, while the host Swedes (2–0–0) and Czechoslovakia (1–1–0) moved on from the three teams in Group C. But while Canada had outscored its opponents 54–0 in two games and the Americans won their three games by a combined 36–6, most experts still favoured the U.S. to win the tournament. Writing in the Owen Sound Sun Times on February 15, 1949, sports editor Bill Dane cautioned that the experts “possibly … are overlooking the best bet of all, Czechoslovakia,” though he undoubtedly wasn’t alone in touting the 1947 World Champions who had given the RCAF Flyers a run for their money at the 1948 Winter Olympics.

Canada faced Czechoslovakia to open the medal round on February 15 … and the game would prove typical of Canadian contests in Europe for years to come. Though the team had been told the CAHA rule book would be used at the World Championship, they had also been cautioned about the referees and told to be careful. But the Czech game got out of hand.

Image of Ray Bauer (SIHR) and action at the Olympic Stadium in Stockholm in 1943. The Stadium was built for the 1912 Olympics and used for the Ice Hockey World Championship in 1949 and 1954. Ray’s son E.J. Bauer says his father always maintained he’d scored eight goals in the 47–0 win over Denmark.