Eric Zweig's Blog, page 27

March 18, 2015

Would 4-on-4 Mean More Goals Get Scored?

With a little more than three weeks to go in the NHL season, the race for the Art Ross Trophy is incredibly tight. And yet there doesn’t seem to be much buzz about it. Perhaps that’s because whether the winner is John Tavares, Alex Ovechkin, Sidney Crosby, or one of the others in the bunch, he’s likely to end up with no more than 86 points. If so, that’ll be the lowest total in a non-strike season since Gordie Howe led the league with 86 points in 1962-63. But, of course, the NHL season was just 70 games long then.

Howe’s points-per-game average of 1.2285 in 1962-63 works out to about 101 points in an 82 game season, whereas 86 points in 82 games translates to only 73 points in a 70-game schedule. Nobody has led the NHL with fewer than 73 points since Max Bentley led the way with 72 in 1946-47. But the season was just 60 games long at that time, so even Bentley’s total would work out 84 points in a 70-game season, or 98 points in 82 games.

Given that no one has led the NHL with less than a-point-per game total since Toe Blake topped the league with 47 points in a 48-game season back in 1938-39, (comparable to 80 points in an 82-game schedule), we’re looking at a fairly historic lack of scoring in the NHL this season.

David Feschuk, writing in the Toronto Star on March 13, noted that the decline in scoring can be traced directly to power-play offense, with man-advantage chances at the lowest level in 50 years. Feschuk quotes St. Louis Blues coach Ken Hitchcock and Nashville Predators’ GM David Poile as saying that everyone seems to be on board these days with what is and what isn’t a penalty and that coaches are happy with the way games are being called.

Yet Feschuk also quotes former referee Kerry Fraser as saying that the current, younger, referees have been insufficiently trained, and that they’re calling minors instead of majors, or sometimes nothing at all, because they’d rather let plays go knowing that anything they missed will be flagged for additional suspensions, if warranted, by the NHL’s video review. Fewer power-plays means fewer power-play goals, and, even worse, calling fewer penalties makes it that much easier to clog things up for the skilled players. The game may be faster than ever before, but that doesn’t mean much if there’s no room to move and no time to think.

Of course, there’s also the argument that scoring – briefly on the rise after the “Dead Puck Era” by the tweaks to the rules introduced in 2005–06 after the season-long lockout ended – is once again on the decline because goalies today are better than they’ve ever been. They may well be. They’re certainly better-trained than they’ve ever been and physically larger too (even if their oversized equipment has been reined in somewhat).

So, if scoring chances have more-or-less remained the same, but goalies (based on their save percentages) are stopping more shots, then what’s the answer? People aren’t saying it as much as they were a few years ago, but is it larger nets? (We’ll look at that next week.) But if there really isn’t enough time and space on the ice, then maybe the answer is fewer players.

Talks are moving forward on some form of 3-on-3 overtime to break more ties before going to a shootout, but there’s little if any talk these days of going to 4-on-4 in regulation time. I’m not saying that 4-on-4 is the answer (and you’ve got to wonder how much the NHL Players Association would support it), but there did used to be a rover in the early days of hockey and the decision to eliminate that extra position (which was first made in 1911-12) worked out pretty well! Not everybody was on board with that in the beginning either. I think it was future Hall of Famer Marty Walsh of the old Ottawa Senators who said that playing hockey without a rover was like playing baseball without a shortstop.

Yet as early as 1946, another early era Hall of Famer, Newsy Lalonde (who survived and thrived after the change from 6-on-6 skaters to 5-on-5) already believed that the best way to allow speed and skill to flourish in the coming years would be to eventually reduce the game to just four skaters and a goalie per side. Future Hall of Famers Ebbie Goodfellow, Joe Primeau and Charlie Conacher shared Newsy’s view, as did Hooly Smith. “There’s no more stickhandling,” Smith complained, “and 90 percent of the goals are scored by passouts from behind the net or from scrambles in front of the goal.”

That’s a complaint that’s pretty familiar!

March 11, 2015

About Face

A month ago, I entitled my story about early hockey radio broadcasts, Hockey Nerd – Part II. This could easily be Part III, but I’ve decided I’m going to try not to refer to myself that way any longer. It was my friend and colleague Roger Godin who set me straight. In my recent story reviewing the film Red Army and discussing the Winnipeg Falcons heritage moment, I referred to my criticism of the Falcons jersey color as being “pretty nerdy.” Roger left a comment, saying: “Let’s rid ourselves of that description ‘nerd.’ Those of us in this business just want to get things right and frequently find ourselves up against a wall of indifference…”

Often times, the problem isn’t the indifference of others but the mountains of misinformation already out there. For example, if you ask people, “who was the first goalie to wear a mask?” most of those who’ll offer an answer will say, “Jacques Plante.” Plante was my first favorite hockey player when I was a boy and he was starring with the Maple Leafs. He had certainly popularized the use of goalie masks, but he wasn’t the first to wear one … even in an NHL game.

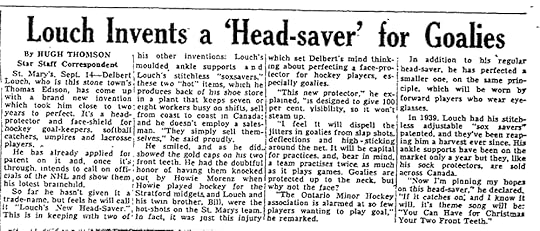

Before he wore one in game action for the first time on November 1, 1959, Plante had been one of many goalies (most of the others at the amateur level) experimenting with masks in the late 1950s. In September of 1957, Delbert Louch of St. Mary’s, Ontario, unveiled a “head-protector and face-shield” that caught on with many NHL goalies for practice, but proved impractical for games.

Long before then, a wore wire masks (like baseball catcher’s masks) in international competition in the 1930s, and many people know that Clint Benedict wore a mask with the Montreal Maroons in February and March of 1930 during his final season in the NHL. Benedict’s was a leather face shield he wore after being sidelined for several weeks following a couple of shots to the face that January.

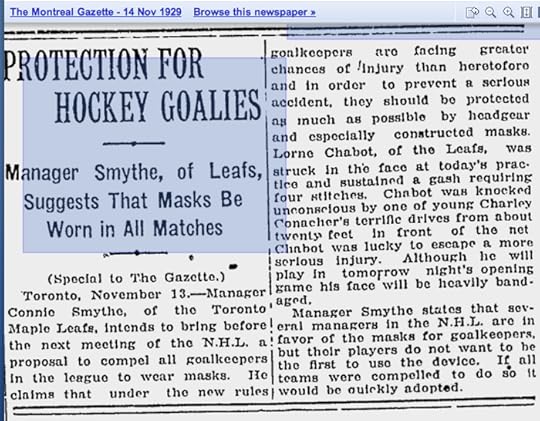

The NHL had modernized its forward passing rules for the 1929–30 season, and just as the schedule was getting under way, Conn Smythe of the Toronto Maple Leafs stated that he planned to introduce a proposal at the next league meeting making it mandatory for all NHL goalies to wear masks. Smythe stated that there were several NHL managers in favor of the move, but no goalie wanted to be the first, so a rule should be adopted to compel them all to do so.

Apparently, the Ontario Hockey Association had passed such a rule for the 1920–21 season saying that goalies may wear a mask for protection though nobody appears to have done so. Despite what Smythe said in 1929, it would be many years before the NHL adopted similar legislation. Amazingly, even as late as 2009–10, the NHL rule book only said that: Protective masks of a design approved by the League may be worn by goalkeepers. The wording was not changed to say must be worn until 2010-11!

These days, the trendy answer to the question who wore the first goalie mask is Elizabeth Graham, who donned a fencing mask while playing net for the Queen’s University women’s team in 1927 … reportedly under pressure from her father who had recently paid for some expensive dental work. However, others had already worn masks before Ms. Graham. The earliest story I’ve come across about a goalie wearing a mask in a hockey game is from the New York Times on February 24, 1916. The Union Club defeated the Knickerbocker Club 14-0 the night before as part of a Charity Ice Carnival for the Belgian Relief Fund during World War I. Knickerbockers goalie J.G. Milburn Jr. was replaced after the first period by J.J. Higginson, who, the Times noted, “wore a baseball mask.”

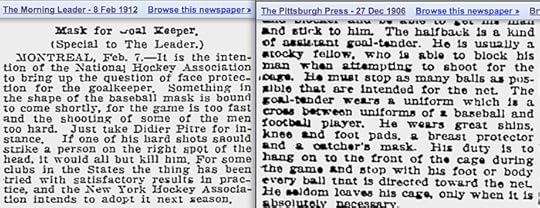

Interestingly, in a story reported in the Regina Leader on February 8, 1912, the National Hockey Association (forerunner to the NHL) was said to be considering the use of face protection for goalkeepers “in the shape of a baseball mask,” which some clubs in the United States were already said to be using in practice. A story about roller polo – essentially hockey played on roller skates – in Pittsburgh in 1906 describes the goalie as looking much like a modern-day lacrosse goalie, and wearing a catcher’s mask. (Perhaps the fact that hockey was not nearly as widely popular in the United States as it was in Canada, and was played mainly at elite schools and swank athletic clubs, meant Americans were less hung up on the “manly” aspects of the game?)

Still, the earliest example I’ve come across of a goalie using a catcher’s mask and/or a leather face shield is from Canada in 1903. Eddie Giroux (often misspelled as Geroux in newspapers) was hurt in preseason practice with the Toronto Marlboros on a shot by teammate Tommy Phillips on December 9, 1903. When Giroux returned to the ice a few days later he was wearing some sort of facial protection. Here’s a quick summary of the newspaper accounts:

• sustained “a nasty cut” in practice – Toronto Globe: Dec. 10, 1903

• skips practice, will return with baseball mask – Toronto Globe: Dec. 12, 1903

• practiced wearing a “padded hood” – Ottawa Citizen: Dec. 16, 1903

• discarded his baseball mask – Toronto Globe: Dec. 17, 1903

• experimented with baseball mask; discarded it – Montreal Gazette: Dec. 18, 1903

• discarded baseball mask, using leather headgear – Winnipeg Telegram reporting from Toronto News: Dec. 21, 1903

Whatever it was Giroux was wearing, he does not appear to have used it when the Marlboros played their first exhibition game in Barrie on December 18, nor in any games that followed during the 1903-04 season. He was said to be having trouble locating shots from the side while wearing it. Baseball catcher’s masks date back to the 1880s, and hockey goalies were quick to adopt cricket pads for added protection during the 1890s, but for now, Giroux’s brief experiment is the oldest usage of a mask by a goalie that I’m aware of.

Giroux wears the pads (but no mask) while seated second from the left with the Marlboros in 1904. Tommy Phillips is seated second from the right. Giroux followed Phillips to the Kenora Thistles in 1905. They won the Stanley Cup in 1907.

March 4, 2015

Glowing Pucks From Hockey’s Past

The NHL recently added many “enhanced” analytic stats to its web site NHL.com. More are likely to come. This year, at the recent NHL All-Star Game, the league introduced sensors in the pucks and uniforms that allow for the tracking of speed, positioning, ice time, and other data that – it’s said – will revolutionize the way we watch and understand hockey. The general buzz around all this has all been positive. VERY different from the much-maligned innovation introduced at the All-Star Game back in 1996 … the Fox Trax glow puck!

It’s not quite the same concept, but take a look at this story I recently came across from the Montreal Gazette back in 1941:

February 25, 2015

Rebuilding in Toronto

Monday, March 2nd at 3 pm Eastern marks the NHL trade deadline. Everyone seems to be in agreement that the Toronto Maple Leafs are now fully committed to rebuilding around youth, although the general consensus is that they’ll be better off waiting until this summer if they plan to trade players such as Phil Kessel or Dion Phaneuf. We shall see…

Everyone also seems to be in agreement that this is the first time the Maple Leafs have fully committed to a youth movement. That’s not entirely accurate. Though this does appear to be the beginning of the first true rebuild since the introduction of the NHL Entry Draft (originally the Amateur Draft) in 1963, it’s certainly not the first one in team history.

After giving up day-to-day control of the Maple Leafs while serving in the Canadian army during World War II, Conn Smythe resumed full charge of the team for the 1946–47 season. Toronto had won the Stanley Cup in 1945 only to fall out of the playoffs the following season, so Smythe and coach Hap Day decided a complete overhaul was necessary. Seven of 21 Leafs players from 1945-46 were traded, released or encouraged to retire. Another four were sent to the minors. The team would go with youth, and though Smythe couldn’t guarantee success, he promised that no team in the NHL would work harder than the new crew he assembled.

Unlike today, how to find and properly develop this new young talent wasn’t much of a concern for Conn Smythe. With no draft and only six NHL teams, it was easy enough for him to rebuild around youth because of the sponsorship of junior and minor league teams that allowed NHL clubs – particularly the wealthier ones; Toronto, Montreal and Detroit – to stockpile young players. (Boston tried the same thing after World War II, but Art Ross didn’t have the financial resources that Smythe did.)

Conn Smythe admitted that he was critical of the 1945–46 version of the Maple Leafs not because they’d missed the playoffs a year after winning the Stanley Cup, but because they had the fewest penalty minutes in the NHL. He vowed that would never happen again under his watch. In his 1980 autobiography, Smythe wrote that he couldn’t remember when he first uttered his famous motto, “If you can’t beat ’em in the alley, you can’t beat ’em on the ice.” He also wrote that his motto was often misunderstood, stating that he didn’t want his players to be bullies, he simply wanted them to refuse to be bullied. Still, while no newspapers appear to quote him using the “alley” expression during the rebuild in 1946, it became pretty obvious that Smythe wanted tough guys in his youth movement.

Smythe “told his players he wanted a fighting team filled with the desire to mix it with anyone,” wrote Jim Vipond in the Globe and Mail on September 27, 1946 as training camp got under way. “He further stressed the importance of team spirit and co-operation.” Gordon Walker of the Toronto Star wrote that same day of Smythe’s “brief, forceful address on club policy,” quoting Smythe directly: “If they start shoving you around, I expect you to shove them right back, harder. If one of our players should get injured by illegal tactics of the enemy, I expect the players on our team to see that the man responsible doesn’t get away with it.”

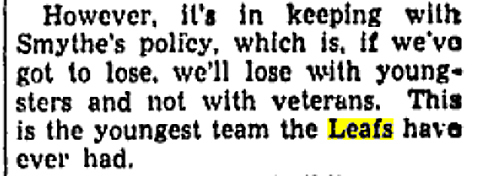

To reshape his team in the image he wanted, Smythe turned to the young players he already had in his farm system, which had been built by Frank Selke, who was now in Montreal after falling out with his longtime boss. Smythe reasoned that if the Leafs had to lose he’d rather lose with youngsters than with veterans and so on September 20, 1946, a week before training camp opened in St. Catharines, Ontario, the Leafs held what would now be called a “prospects camp.” The best from that group were invited to the main camp and were there when Smythe delivered his forceful address.

From that prospects camp emerged Bill Barilko (though he would begin the season in the minors), Gus Mortson and Howie Meeker, who would all be a part of four Stanley Cup–winning teams in Toronto over the next five years. Jimmy Thomson’s brief appearance with the Maple Leafs in 1945–46 had already earned him a spot at the main camp, where he too made the team and won four titles in the next five years. Three-time Cup-winners Garth Boesch and Vic Lynn also came out of the prospects camp, as did Tod Sloan although he needed a few more years to develop into the star he would become in 1950–51. Sid Smith hadn’t been there, but did make a brief debut in the NHL in 1946–47 before breaking out as a star a few years later. (There was, in fact, so much young talent in Toronto that Smythe would deal five players to Chicago the following season to land veteran Max Bentley.)

Smythe was confident entering the 1946-47 season that he’d put together a team he might win with a year or two down the road. Having Syl Apps and Turk Broda back in pre-War form, and with twenty-one year old Teeder Kennedy already entering his fourth season, certainly helped, but with six rookies among 12 new faces on the 18-man roster, Smythe down-played his expectations. “The Maple Leafs will suffer plenty of defeats this season,” he admitted. But he couldn’t completely hide his optimism: “We’ll win plenty, too!”

With a team that refused to back down from anyone, the Maple Leafs finished a surprising second behind the Canadiens in the regular-season standings. Frank Selke was critical of Toronto’s style all season, and early in the year he accused Maple Leafs defensemen of using “wrestling tactics.” There was plenty of rough stuff when the two teams met in the Stanley Cup Finals … which Toronto won to launch the club’s first dynasty.

It’s unlikely the rebuild will go quite as quickly this time!