Eric Zweig's Blog, page 25

August 20, 2015

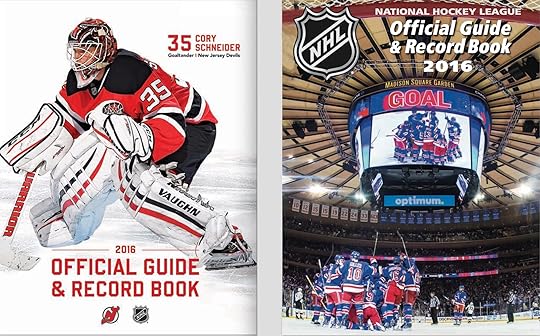

One Book to Guide Them

The NHL Official Guide & Record Book was completed this week and sent to the printer. This will be the 84th edition of a book that dates back to the 1932-33 season. Milt Dunnell, the dean of Canadian sportswriters who died at the age of 102 in 2008, used to send a note to Dan Diamond every year saying something along the lines of, “Jim Hendy could never have guessed what his little pocket guide would become.”

Jim Hendy worked on what he called The Hockey Guide until 1951, after which he turned over the book to the NHL. Through expansion after 1967 and right into the 1980s, the book maintained its “pocket” format, although as the NHL grew from six to 21 teams it was split into two books: a Guide and a Register. In 1984, Dan Diamond proposed a reorganization and redesign that saw the NHL Official Guide & Record Book remodelled into magazine-sized pages including photographs for the first time. Dan’s first Guide was 352 pages. Over the years, it’s grown to 672 pages!

The National Cover

No matter what the size, Dan Diamond & Associates takes its mandate of being the NHL’s Official Guide very seriously. A tremendous amount of care and attention goes into being accurate. Obviously, the NHL Communications department aids greatly in this, but you can help too. Every year, a note in the Guide states: “We appreciate comments and clarifications from our readers” and that, “Your involvement makes a better book.”

This year, we corrected a decades-old error in Alec Connell’s record from 1927-28 for the Longest Shutout Sequence By a Goaltender based on an article Don Weekes wrote last fall for The Hockey News and brought to our attention. (And, yes, we go with Alec. Although Connell’s given name was Alexander and many call him Alex, Alec does seem to be what he went by himself for most of his life.)

Dallas and Montreal custom covers

I’ve been working with Dan Diamond & Associates since the summer of 1996. Among the many jobs I do, it’s been my responsibility for the last decade or so to assemble statistical panels for newly drafted North American players that will appear in the Guide’s Prospect Register for the very first time. As often as possible, we like to include a line of statistics from a player’s last year of minor/youth hockey before he moved up to Junior A or college. There are many web sites that aid the cause these days, though I always like to double-check (and often triple-check) what’s on any stats-specific site against what’s on a league or a team’s web site. Every summer, there are numbers that don’t match or can’t be found, and can only be resolved by contacting a team, or a coach, or a parent directly.

It’s always fun talking to a proud coach or parent in the weeks after a young player has been selected in the NHL Draft. This past spring (even before the NHL Draft was held), I had the opportunity to “talk” via email with Connor McDavid’s father to try and clarify his son’s statistics from his last year of midget hockey with the Toronto Marlboros of the GTHL.

Devils and Rangers custom covers

I had noticed that while every stats site seemed to have the same amazing totals for McDavid’s spectacular 2011-12 season (88 games, 79 goals, 130 assists, 209 points), none of the sites that broke down his numbers into season games, playoff games and tournament games showed the same results. A big deal? Not really. But I thought that if Connor McDavid was going to be the next great NHL superstar everyone believes he will be, it would be nice to get it right! Turns out, Connor’s father felt the same way.

I contacted the Marlboros (who, I know, from past years, do not officially keep statistics for their players) and they put me in touch with Brian McDavid, who had tracked all of his sons stats that season. “Please don’t lump me into the ‘crazy hockey dad’ category for doing this,” he wrote, “but I felt Connor had a chance to be a significant player in the game in the future and … that his season would be lost from a statistical view if I didn’t do it myself.” He sent me an Excel sheet showing Connor’s performance game-by-game, not only for the Marlboros that season but also for his team at the PEAC School for Elite Athletes in North York (a Toronto suburb).

Colorado and Calgary custom covers

So, while we can’t match the up-to-the-minute aspect of the many sports web sites out there these days, you’ll be hard pressed to find any one site on the Internet that can give you all the information as neatly and concisely as that contained in the NHL Official Guide & Record Book … and I dare say you’ll have an even harder time finding one that does so with such attention to detail.

This year’s Guide will be in bookstores in early September. Or you can order it online right now at the dda.nhl eBay site.

August 11, 2015

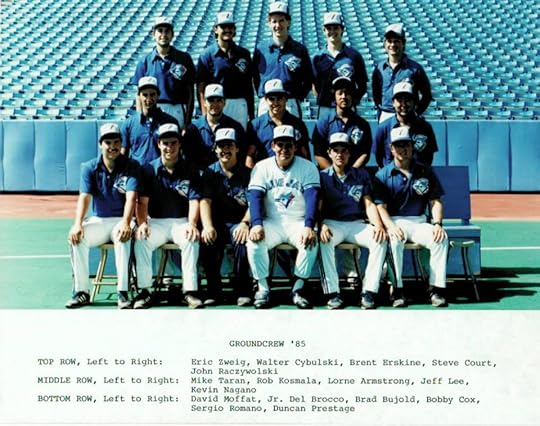

Rhapsody in Blue Jay

I’ll admit it. I’ve been pretty pessimistic when it comes to the Blue Jays over say, the last 22 years. Can you blame me? But, to my credit (or maybe not), I’ve never bailed on them. Now that I live in Owen Sound, I don’t get to see them live nearly as much as I used to, but I keep watching on television night after night after night. I haven’t always been sure why I do. Sometimes, it felt like a strange kind of loyalty to my younger self.

Still, I kept watching. But any time I was foolish enough to even let myself start to believe for a short time, they’d break my heart. Now? I’m pumped! This past weekend in New York was amazing. And – even though it’s August and not September – it got me thinking back to the pennant race of 1985 … the first time Toronto won the American League East.

As many of you know, my family lived and died with this team in those days. (OK, we still do!) We still have the season tickets we’ve had since the moment they went on sale prior to the first season in 1977. I grew up with this team and it was a blast! In 1985, I was in my fifth and final year on the Blue Jays ground crew as the team made the journey from worst to first.

On August 4, 1985, the Blue Jays were 67-39. They were 9 1/2 games up on the Yankees in the American League East. Over the next five weeks, the Jays went 21-12. They Yankees went 29-6. They had two seven-game winning streaks and an 11-game streak during that stretch. Every night, it seemed, they were trailing, only to rattle off a big inning late in the game to pull out a victory. It was testing my faith.

There was an old security guard who worked in the Blue Jays bullpen in those days. I’m very sorry I can’t remember his name. I loved talking with him. As a boy in 1930s, he’d lived in New York and worked at the Polo Grounds. As on old man (in the days long before the Internet), he carried papers in his pocket on which he tracked all of baseball’s all-time leaders and which current players were gaining on them.

I remember walking out to the bullpen one day and admitting to him how nervous I was getting. Dennis Lamp (who went 11-0 in relief that year) glared at me. People may remember a picture of him in the clubhouse after the Jays clinched, pointing to a sign he’d made that said something along the lines of, “People counted this team out, but we never heard the bell.” I’ve never told anyone this before, but I sort of felt he was talking to me. But that’s getting a little ahead of the story…

When the Blue Jays headed into New York to begin a four-game series on September 12, their once-big lead was down to 2 1/2 games. That Thursday night, the Jays were leading 4-1 through six innings. But as they had done for weeks, the Yankees rallied in the seventh. Two brutal errors by Tony Fernandez led to six runs on just three hits. The Yankees won the game 7-5.

Amazingly, the Blue Jays bounced back. They won the next three in a row, and stretched their lead back to 4 1/2 games. Though things got nervously tight again over the next couple of weeks, Toronto clinched the AL East Division on October 5, 1985, with a 5-1 victory over the Yankees.

I was right there on the field a few seconds later, assigned the job of protecting home plate in case any excited fans wanted to dig it up as a souvenir. In some of the film footage (unfortunately, not the TV footage you can find on YouTube) you can clearly see me running onto the field, hugging a fellow ground crew member, and then turning to face the stands, where my brother Jonathan had been sitting, and waiting for him to race onto the field to leap into my arms.

The World Series wins were great. My wife Barbara and I often remember the nervous feeling in our stomaches as Game Six in 1992 went into extra innings, and I remember wading through a room full of people after the game, struggling to reach and embrace my brother David. But for me, 1985 will always be special. It staggers me to think it was 30 years ago…

July 29, 2015

Chasing Art Ross

As many of you know, my newest book will be out this fall. It’s a biography of hockey legend Art Ross. Early last month, I wrote the following email:

From: Eric Zweig

Subject: Biography of Art Ross

Date: June 8, 2015 at 12:06 PM EDT

To: Bryan Trottier

Dear Mr. Trottier,

My name is Eric Zweig. For nearly 20 years, I have worked with the small publishing company that creates the NHL Official Guide & Record Book. I am also the author of more than 20 books about hockey and hockey history for both children and adults. You and I met several years ago in Kenora during the 100th anniversary celebration of the Kenora Thistles’ 1907 Stanley Cup championship. I spoke at the dinner about Art Ross’s contributions to the team.

This fall, I have a book coming out with Dundurn Press in Toronto that will be the first full-scale biography of Art Ross. In order to generate publicity for the book, several Canadian hockey writers have agreed to read advanced copies and (hopefully!) offer positive comments. Scotty Bowman and Harry Sinden have also agreed to do this. I am hopeful that you, as a past winner of the Art Ross Trophy, might be willing to provide a brief, written, comment about the experience of winning the Art Ross Trophy.

Thank you, and I look forward to hearing from you.

To be honest, I wasn’t sure he would even receive the message. I certainly didn’t expect he’d remember me, and could easily imagine an email from an unknown address going directly to spam, or being deleted without a second thought. But to my delight, barely an hour later, I received the following response. I thought it was pretty amazing, and with Bryan Trottier’s permission, I share it with you now:

From: Bryan Trottier

Subject: Re: Biography of Art Ross

Date: June 8, 2015 at 1:14 PM EDT

To: Eric Zweig

Hi Eric

Winning the Art Ross Trophy was an interesting quest and achievement. The 1978-79 season was a strong year for our team [the New York Islanders]. Our line was having a terrific offensive year and Mike Bossy was on a tear scoring goals. We rode the wave and were too young and dumb to recognize any pressures. We were just doing something we loved to do.

I do remember feeling a bit selfish, which was uncomfortable, but as the season was winding down, I started to recognize how my teammates and Al [Arbour, our coach] were rooting for me. Everyone was making it almost a team mission. This I loved most! “Lets help Trotts win it.” I needed the support and talents of teammates… Clark Gillies, Mike Bossy, Denis Potvin were huge talents, [John] Tonelli, [Bob] Bourne, etc. I needed quality ice time from the head coach. [Al’s] combination of line mates and power-play groups — double shifting was helpful. I also needed the selflessness of some of the other center men sharing their ice time.

I believe Guy Lafleur and I were tied going into the last game of the season. I was in New York versus the Rangers and he was in Detroit facing the Red Wings, who were having another trying season. I thought, “Uh oh…” And Marcel Dionne had just had a five-point night to catch us as well, I think. I ended up scoring a goal and assist while Jim Rutherford shut out the Canadiens. I remember watching the out-of-town scoreboard and being amazed at what Detroit was doing. I came to the bench a couple times and Al asked if I could go again. “Wow, he’s really giving me every chance possible,” I thought, and Mike Kaszycki and Wayne Merrick were telling me to take their next shift. Wow, forever grateful to two great, selfless teammates. Dave Lewis, Ed Westfall, Bob Nystrom were all urging and prodding. “You may never get another whack at this kid,” so “go for it!” was their message.

I don’t believe I ever made a public declaration that I wanted to win the Ross, and I think Al Arbour and [GM] Bill Torrey liked that I was a bit reserved and guarded as to my comments or answers to the press when asked about the race. But it was there and I did give it my very best as I didn’t want to waste the opportunity afforded me by fate, teammates and coach/management. I do remember the Long Island fans loving it as the fan mail was full of well wishers, and I remember Mike Bossy being as proud as a brother when the season ended. “Feels good, huh?” he said. To which I said, “Thanks, Boss!” Enough said. We both knew what the other was thinking. “Couldn’t have done it with out ya!”

A few years ago, I was at an alumni event and a random hockey fan came up to me and told me that I was one of three players in the history of the game to win the Art Ross, the Hart, the Calder, the Conn Smythe, plus the Stanley Cup at least twice. I wouldn’t be in this group if not for Jim Rutherford and a 1979 Islanders team that pushed, supported, encouraged and motivated me.

I wish I knew more about Mr. Ross as a player, coach, manager, innovator, etc. Your research and creative writing will be of great interest. It will be an honor to read the book.

Bryan Trottier

July 14, 2015

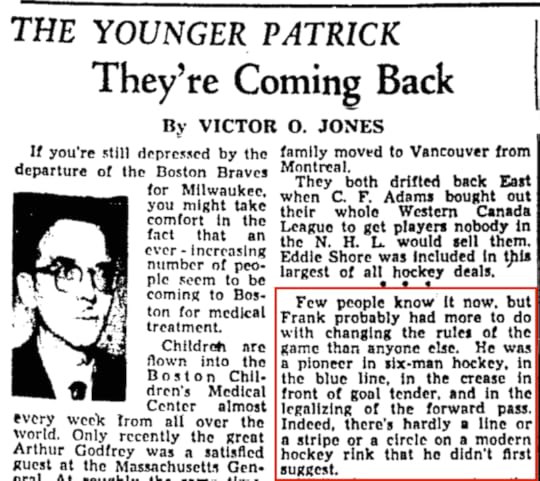

Visions of the Future

At the end of October, shortly after the World Series, I wrote a piece about Lester Patrick’s hockey vision for baseball’s future. With the All-Star Game tonight, we’ll check in on Frank Patrick’s thoughts on how to improve baseball. Frank is widely considered to have been the more inventive of the two Patrick brothers when it came to modern hockey rules, but his future vision for baseball didn’t pan out as well as Lester’s.

In his column in the Boston Globe on August 5,1953, Victor O. Jones recalled the days of 1934 to 1936, when Frank had served as coach of the Bruins during the depths of the Great Depression.

The 1934-35 Boston Bruins. Frank Patrick is seated third from the right.

Creator: Leslie Jones, 1886-1967 (photographer).

Publisher: Boston Public Library, Print Department BPL 08_06_011885

Leslie Jones-The Camera Man

“He thought baseball could attract more interest if it marked the field a little more elaborately,” Jones recalled. “He want to lay down chalk lines dividing left, center and right field and also proposed that circular lines be drawn at every 100 foot radius from home plate. Frank got this idea from listening to a radio broadcast of a game. He thought if the announcer could say: ‘He hit that one beyond the 300 foot circle,’ the fans would get a better idea of just how far the batter hit the ball.”

Not much of a concern once television replaced radio, but Jones writes of another Frank Patrick brainchild that was much more visionary. “Soon after he came up with another idea – a covered building large enough to play football games inside it, with moveable sections of stands which could be rolled around to provide, from day to day, a field of play for any kind of sport from football and polo to swimming and boxing.”

Jones wrote that “Frank Patrick went so far as to get an engineer to draw plans for such a stucture,” and that his domed stadium was “entirely possible from the engineering point of view.” Jones notes, however, that this was during the Depression and that “money was scarce.” Still: “Don’t be surprised someday, though, if you see such a structure.”

Interestingly, in his 1980 biography of the clan entitled The Patricks: Hockey’s Royal Family, Eric Whitehead writes that plans for Frank’s dome were drawn up around 1947 or 1948. He applied for copyrights in Ottawa and Washington, but couldn’t find any financial backers. On this one, he was truly ahead of his time.

Frank Patrick died on June 29, 1960. Ground was broken for construction of the Houston Astrodome on January 3, 1962. These days, few true domed stadiums remain, but you’d have to think that Frank would be impressed with the evolution of retractable roof stadiums since the SkyDome opened in 1989.

(NOTE: The front row in the top picture is comprised entirely by future members of the Hockey Hall of Fame. Who can name them all in addition to Frank Patrick?)

June 30, 2015

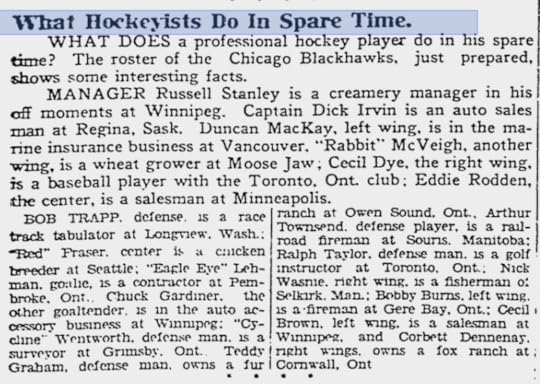

The Summer Season

This year’s members of the Chicago Blackhawks will probably spend the summer much differently than did their predecessors of years gone by. From the Pittsburgh Press in 1927:

However you’re planning to spend your summer, I hope you have a happy Canada Day or Fourth of July.

June 23, 2015

Hod Stuart Was Here

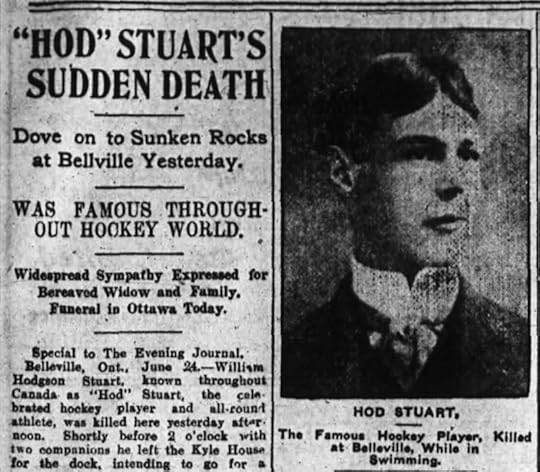

On June 23, 1907, Hod Stuart died at the height of his hockey career. He was 28 years old. Some of you reading this will recognize his name right away. Others won’t. But 108 years ago today, news of his death would have been like hearing that Sidney Crosby or Jonathan Toews had just been killed.

Hod Stuart was a defensemen (a cover point in his day), so a better comparison might be made to Drew Doughty, P.K. Subban, or Erik Karlsson, one of whom will win the Norris Trophy tomorrow as this past season’s best NHL defender. Given his status as the game’s highest-paid player, perhaps Stuart was most like Nashville’s Shea Weber – although during the 1906-07 season when hockey players were first allowed to earn salaries in Canada, you’d have to add a lot more zeroes before Stuart’s salary (which was somewhere between $1,200 and $1,500) matched the $14 million Weber makes.

William Hodgson Stuart, the son of William Stuart and Rachel Hodgson, was born in Ottawa on February 20, 1879. His father was a well-respected contractor and the captain of the Ottawa Capitals lacrosse team. Young Hod played football and hockey in Ottawa at the end of the 1890s, but moved to Quebec City in 1900 on a contracting job for his father. He played hockey there too, and met his future wife, Marguerite Cecilia Loughlin, whom he married in 1901. By 1907, they had two young children.

Hod Stuart had yet to emerge as a hockey star while playing in Ottawa and Quebec, but did so quickly after 1902 when he began to play in the United States – where players were already allowed to earn a salary. Canadian fans needed convincing when Stuart left Pittsburgh in late December of 1906 to play for the Montreal Wanderers, but his play was outstanding and the press reports were just as glowing. Late in his life, Art Ross would say that Hod Stuart was the only defenseman he’d ever seen that was in a class with Eddie Shore.

Despite what many sources say, Stuart was not yet with the Wanderers when they defeated a team from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia in a preseason Stanley Cup challenge at the end of December. He joined the team in time for its first regular-season game on January 2, 1907 and starred in the Wanderers’ Stanley Cup series with the Kenora Thistles two weeks later. The Thistles won, but the Wanderers bounced back to finish their 10-game season with a perfect 10-0 record and Stuart was a big part of their winning back the Cup in a rematch in Kenora at the end of March.

After the hockey season, Stuart returned to Ottawa but was soon at work for his father’s construction company overseeing a building project in Belleville, Ontario. On a leisurely Sunday, he spent the morning canoeing with friends. In the heat of the day around 3 o’clock, they returned to the waterfront. Hod was a strong swimmer, and he jumped in from the Grand Junction dock to cool off, swimming about a quarter-mile to a nearby lighthouse.

Hod Stuart’s wife and daughters, circa 1910, courtesy of johnnysgirl668 on Ancestry.com

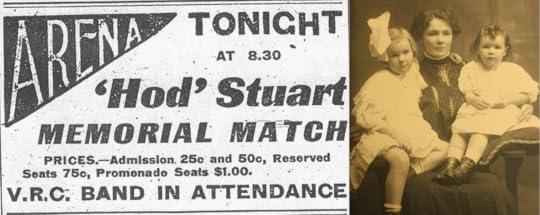

There was a small platform around the lighthouse, about six or eight feet above the water, and those watching from the dock saw Stuart climb up and rest for a few minutes before diving in again. He didn’t re-surface. Unaware of how shallow it was in certain places around the lighthouse, Stuart struck his head on a jagged rock just two feet below the waterline. He suffered a fractured skull and a broken neck, and was said to have died instantly. On January 2, 1908, the Wanderers defeated a team of all-stars in the Hod Stuart Memorial Game, which raised just over $2,000 for Stuart’s wife and daughters. In 1945, he was among the first inductees into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

The story of Hod Stuart’s death is what I intended to write about today, but in researching his life I came across something pretty amazing. In the spring of 1897, when he was just 18 years old, Stuart left Ottawa with another local boy, sponsored by a group that included Hod’s father, to seek his fortune in the Klondike, where gold had been discovered during the summer of 1896.

As I wrote last week about the Spanish-American War, the Klondike Gold Rush is among my many wide-but-not-deep historical interests, and in a letter written to his father on May 31, 1897 (as reported in the Ottawa Journal on July 27), Hod rhymes off many familiar names:

“We left Dyea, an Indian village, Sunday…. We towed all the stuff up the river seven miles and then packed it to Sheep’s Camp…. A beautiful time we had I can tell you, climbing hills with fifty pounds on our backs…. We left Sheep’s Camp next morning at four o’clock, and reached the summit at half-past seven…. The Chilkat Pass [note: though the Chilkat Pass was a route to the Klondike, this is likely a misspelling of the more famous Chilkoot Pass, which was just beyond Sheep Camp] is not a pass at all, but a climb right over the mountains…. It was an awful climb – an angle of about fifty-five degrees. We could keep our hands touching the trail all the way up. It was blowing and snowing…”

Another letter, written on June 28, appears in the Journal on October 12, but there’s not much news after that. However, on April 7, 1898, the Journal notes that Hod was among the first Ottawa parties in the gold fields, and that his father “has learned from time to time that his son has been doing well.” Astoundingly, William Stuart had left for the Klondike the night before, having contracted to build the Bank of Commerce building in Dawson City. By September of 1898, father and son were back in Ottawa. Hod failed to seek his fortune in gold, but soon found fame as an athlete.

Pulford is Hockey Hall of Famer Harvey Pulford, although this clip refers to Hod Stuart’s senior football debut with the Ottawa Rough Riders on Thursday, November 24, 1898.

June 17, 2015

Fun in Black and White

Sometimes, it hard to imagine that the people in really old black-and-white photographs actually lived in a colorful world. Yes, their music sounds funny to modern ears (and their humor often doesn’t!), but they found ways to have a good time! Maybe hockey fans in the early days of the Stanley Cup weren’t making as much noise as the fans in Chicago at the Madhouse on Madison the other night, with their amped up, piped in sound explosions, but they weren’t sitting on their hands either.

A few years ago, I was reading old newspaper stories about the 1903 Stanley Cup series between the Montreal Hockey Club (usually known now as the Montreal AAA) and the Winnipeg Victorias, played between January 29 and February 4 of that year. A story in the Montreal Herald referred to the fans amusing themselves by shouting out “scraps of songs.” Often, they broke out into In the Good Old Summer Time, which came out in 1902 and quickly became a hit. It was decidedly the dead of winter in Montreal, but the weather was unusually mild that day and the natural playing surface was soft and slushy. “Was it a reference to the conditions of the ice is a question we must leave to the gentlemen who sang it,” said the Herald of that song.

But it was the lyrics from another scrap of song the fans were singing that interested me:

“Who drove the Spaniard back to the tanyard?

Why Mr. Dooley-ooley-ooley-[ooley]-oo.”

Among the many items of my wide-but-not-very-deep historical interests are Teddy Roosevelt and the Spanish-American War of 1898. Given the timing, I figured it must have something to do with that. But what?

Turns out, Mr. Dooley was a fictional character created by a Chicago newspaper writer named Finley Peter Dunne around 1898. Mr. Dooley – according to Wikipedia – “expounded upon political and social issues of the day” with sly humor. (Think Jon Stewart, or Stephen Colbert.) Mr. Dooley became so popular that Dunne’s columns were soon syndicated across the United States. By 1902, he’d published five Mr. Dooley books. Teddy Roosevelt was big fan.

That same year of 1902, the American songwriting team of William Jerome and Jean Schwartz put Mister Dooley to music. Though it seems to have nothing to do with the plot of either play, the song was added to the Broadway staging of a 1901 London show called A Chinese Honeymoon when it opened in New York on June 2, 1902. It was also included in a stage production of The Wizard of Oz which opened in Chicago two weeks later and had moved to New York earlier in January of 1903. Mister Dooley was so popular, it sold over a million copies.

It might not have the same celebratory quality as Chelsea Dagger by The Fratellis, which has become a huge hit with Blackhawks fans in recent years, but Mister Dooley was definitely an early earworm. Think “Who Let the Dogs Out / (Who, Who, Who, Who?)” only a lot less Calypso-Hip Hop and a lot more Tin Pan Alley.

Despite the fact there were already ten verses, each with a different version of the chorus, people seemed to enjoy writing their own new words to suit various occasions. And everyone was singing it; from school kids, to advertisers, to the Grand Duke Boris, brother of Czar Nicholas II of Russia, accompanied by a bevy of chorus girls while in Chicago in the late summer of 1902.

And what did Mister Dooley sound like? Well, have a listen!

June 10, 2015

Mr. Stopper from Stopperville

Tampa Bay’s Ben Bishop has already beaten Carey Price and Henrik Lundqvist in the playoffs. If the Lightning win the Stanley Cup – which Price’s Canadiens and Lundqvist’s Rangers have yet to do – is Bishop a better goalie than they are? If Chicago’s Corey Crawford winds up winning his second Cup, is he a better goalie?

Few people are going to say yes. After all, even the greatest goalie can’t win all by himself. But having a good goalie certainly doesn’t hurt.

Way back in 1917, when the NHL was starting out as a four-team circuit, hockey experts already knew that a top team needed a top goalie. The Montreal Canadiens had Georges Vezina. The Ottawa Senators had Clint Benedict. Both were future Hall of Famers, and could certainly be considered the Carey Price and Henrik Lundqvist of their day (though both had already won the Stanley Cup by then). Even the Montreal Wanderers, whose owner Sammy Lichtenheim and coach Art Ross were publicly bemoaning the plight of their undermanned team, had Bert Lindsay in goal. Lindsay – the father of Red Wings legend Ted Lindsay – was no superstar, but a solid goaltender in his own right. (Let’s say he was Corey Crawford – though without a Stanley Cup win.)

Who did Toronto have in net entering the 1917–18 season? The tandem of Art Brooks and Sammy Hebert. Their modern equivalents might be the two worst starting goaltenders in the American Hockey League.

On the first night in NHL history, December 19, 1917, Hebert gave up five goals in the first period in Toronto’s game against the Wanderers. Hebert was replaced by Brooks, who gave up five more through the next two periods. The Wanderers won 10-9. Offense ruled in this era, and NHL teams would average close to five goals a game during the 1917-18 season. Even so, TORONTOS WEAK IN THE NETS read a headline in the next day’s Toronto Star. On December 21, the Ottawa Journal noted: “one swallow does not make a souse, and one game doesn’t afford much of an indication as to the future possibilities of a [season] but … it seems safe to hazard the following…. Toronto needs more balance on the attack, and a netminder of class.”

Toronto looked much better in its home opener on December 22, crushing Benedict and the Senators 11-4. Four nights later, Toronto beat Vezina and the Canadiens 7-5. “Brooks, in goal,” the Star reported, “looked like Mr. Stopper from Stopperville.” The writer appears to have been serious, but then the team dropped its next game 9-2 to the Canadiens in Montreal on December 29. The Toronto World said the “Torontos are still suffering from the want of a goal-tender.”

Toronto made a change in net in Ottawa on January 2, 1918 and won 6-5. The World reported that “both Sammy Hebert and Clint Benedict [played] remarkable games,” but by now newspapers had been reporting for weeks that Toronto was after Harry “Hap” Holmes – another future Hall-of-Fame goaltender. (If Vezina and Benedict were Price and Lundqvist, perhaps Holmes, with his two Stanley Cup wins, was Jonathan Quick.)

Hap Holmes was from the Toronto area, born in Aurora, Ontario, in 1892 and raised in Clarksburg – between Collingwood and Owen Sound – but living in Parkdale since at least 1911. He’d won the Stanley Cup with the Blue Shirts of the National Hockey Association in 1914, but was one of several Toronto players lured to the Pacific Coast in 1915 – where he won the Stanley Cup again with the Seattle Metropolitans in 1917. Now, Hap had a chance to play at home again … but the Wanderers (for reasons that seem somewhat dubious) owned his NHL rights.

Toronto was reluctant to meet Sammy Lichtenheim’s asking price of Reg Noble (the team’s best player), but then fate intervened. A fire destroyed the Montreal Arena, and while the Canadiens moved across town to the Jubilee Rink, the woeful Wanderers dropped out of the NHL, leaving the league with just three teams. “The blue shirts will get Harry Holmes,” the World reported on January 4, “and will be strengthened in their only weak spot.” The following day, the paper opined that with Holmes in net, “the blue shirts will be a hard team to beat.”

The Montreal Canadiens won the first half of the NHL’s split-season schedule, but Toronto won the second half and then defeated Montreal in the playoffs. Next, they beat the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association three games to two in a best-of-five Stanley Cup series. It was a high-scoring affair until Toronto won the last game 2-1 in a tight goaltending battle between Holmes and Hugh Lehman – another future Hall of Famer. (Roberto Luongo, maybe … but with a Stanley Cup ring!)

Said the Vancouver World after the series: “Too much praise cannot be paid to Harry Holmes for his exhibition in the nets. Harry has his eye on everything and he made many startling saves.… His net guarding was one of the strongest points of the Toronto defence, and it certainly went more than half way in winning the honors.”

When it mattered most to his team, Hap Holmes was Mr. Stopper from Stopperville. Who will it be this year?

June 3, 2015

Hockey Warriors

The Oshawa Generals won the Memorial Cup on Sunday, defeating the Kelowna Rockets 2-1 in overtime in the final game. The championship trophy for Canadian junior hockey has been competed for annually since 1919.

Originally known as the OHA Memorial Cup, it was the brainchild of Captain James T. Sutherland of Kingston, a hockey pioneer of the first order who conceived it as a way of honoring the many athletes who’d given their lives fighting in the First World War. Sutherland particularly wished to commemorate two fellow Kingston men whom he coached in their home town: and .

Back in November for Remembrance Day, I posted a story I wrote last year about Davidson, Richardson and others for the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Legend’s magazine. Today, I’m attaching a story written originally as a sample chapter for a book proposal about Scotty Davidson, detailing the battle in which he lost his life 100 years ago. It’s quite long, but I hope you’ll click here and take the time to read it, or at least save it to read later.

May 27, 2015

Hell Freezes Over

I don’t mean to write off Chicago, and certainly not New York. Nor do I truly intend to demean the Ducks or the Lightning. But could anything say hockey LESS than Anaheim, California, facing Tampa, Florida, for the Stanley Cup … in June!?!

It would be a kick in the teeth for Canadian fans who await our country’s first NHL championship in 22 years and counting.

Hell will have truly frozen over.

Well, OK, maybe not. But when Montreal last won the Stanley Cup in 1993, it marked the eighth time in ten seasons that a Canadian team had won the title. Canadian teams were outnumbered by Americans at least two to one during the 50 seasons from 1944 through 1993, but Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton and Calgary still took home the Stanley Cup 35 times!

What’s happened since?!?

In the earliest days of hockey, Canadian teams won the Stanley Cup all the time. That’s because when Lord Stanley donated his trophy in 1893, he intended it to be awarded to the championship team in the Dominion of Canada. The first official Stanley Cup enquiry by an American team came in February of 1907 when the Pittsburgh Pros announced they would challenge for the Stanley Cup if they won the International Hockey League championship. On February 15, 1907, The Globe in Toronto reported that Stanley Cup trustee Philip Dansken Ross would refuse the challenge. “Trustee Ross of the Stanley Cup says the trophy is for Canadian competition only…”

Five years later, Ross’s fellow trustee William Foran refused to even accept the idea that two Canadian teams might play for the Stanley Cup on American ice, even if only to take advantage of the artificial ice in the Boston Arena. “Defending teams may play for the silverware in any rink or in any city they may choose, but not in the United States. The cup was donated for the championship of Canada, and we will certainly oppose any move to play for it outside the Dominion.”

But on December 8, 1915, the trustees changed their tune. “The Stanley Cup is not emblematic of the Canadian honors,” said Mr. Foran, “but of the hockey championship of the world. Hence, if Portland or Seattle were to win … they would be allowed to [claim] the trophy.”

Why the sudden change? Well, at this time hockey had two major leagues: the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. Like the NHL and the WHA many years later, players would pit owners against each other, jumping from league to league and driving up salaries. But with the NHA continually breaking its agreements with the PCHA, there was a very real chance that the Stanley Cup would be scrapped. Declaring that the PCHA’s American franchises could compete for the Cup was a way to help keep the peace. In 1916, the Portland (Oregon) Rosebuds became the first American team to play in a Stanley Cup series. They were beaten by the Montreal Canadiens. A year later, the Seattle Metropolitans defeated Montreal, and the Stanley Cup went south of the border for the very first time.

The NHL replaced the NHA in 1917-18, but didn’t expand southward until the 1924-25 season when the addition of the Boston Bruins (as well as the Montreal Maroons) saw the league grow from four teams to six. By the 1926-27 season, the NHL had grown to ten clubs with six of them based in the United States. American teams have outnumbered Canadians ever since. In 1928, the New York Rangers became the NHL’s first American Stanley Cup champion and one year later, the Bruins defeated the Rangers in the first All-American Stanley Cup Final.

Sportswriters in American cities found the NHL’s protracted playoffs to be laughable, even in 1929 when Boston wrapped up the season on March 29. The Bruins had already beaten the Rangers to finish first in the American Division during the 1928-29 regular season, so why did they have to play them again for the Stanley Cup? This certainly didn’t happen in baseball, where only the first-place teams in the National and American leagues advanced to the World Series.

“[W]hy not evolve some plan for flooding and freezing the ball parks,” wondered a writer known only as “Sportsman” who penned the Live Tips and Topics column in the Boston Globe, “and [have] hockey all summer?”

Hmmm. Maybe the NHL has missed something by staging all those outdoor games in the dead of winter!