Eric Zweig's Blog, page 21

May 31, 2016

Killaloe Kids BookFest

On May 26 and 27, I visited the Ottawa Valley communities of Barry’s Bay, Wilno and Killaloe to take part in the very first Killaloe Kids BookFest. I had a great time, and it seemed like everyone else did too!

These pictures are all from my visit to Killaloe Public School, who were also hosting older grades from St. Andrews.

If you’d like to bring me to your school or library, please click on the Speaking link at the top of this page for more information.

May 25, 2016

Superstitious or Silly?

The Penguins stayed alive in the Eastern Conference final last night, forcing a seventh game on Thursday before we’ll see the Prince of Wales Trophy presented. San Jose could wrap up the Western Conference tonight with a win over St. Louis to claim the Clarence Campbell Bowl.

Though they’re both impressive pieces of silverware, the Conference trophies just don’t mean the same as the Stanley Cup. So much so that it’s become something of a tradition in recent years not to touch the Conference championship trophies (the belief being “This isn’t the trophy we’ve been playing for. We want the Stanley Cup”) – and something of a sport to watch and see who does or doesn’t.

Even as superstitions go, this one’s kind of silly. There’s clearly been no correlation whatsoever between which teams touch or don’t touch these trophies and then go on to win or lose the Stanley Cup. And more often than not, BOTH teams don’t touch it, but only one can win.

(If you want to read more about the history and quirks of this superstition, you can check out these links: thehockeywriters.com and broadstreethockey.com)

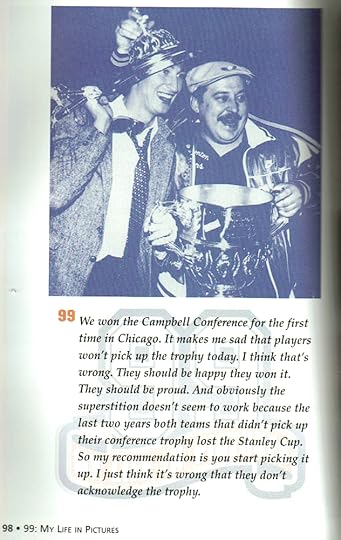

As early as 1999, when we at Dan Diamond and Associates worked on Wayne Gretzky’s 99: My Life in Pictures, The Great One already believed this was a dopey new superstition:

Donated to the NHL in 1925, the Prince of Wales Trophy has been awarded for many things over the years. It’s been presented to a conference champion en route to the Stanley Cup Final since the 1981–82 season, but from 1938–39 to 1966–67, it was presented to the team that finished in first place in the NHL regular-season standings. Sometimes, the circumstances in which it was presented were less than glorious.

In 1967, the Chicago Black Hawks finished first in the NHL standings for the first time in franchise history. They clinched first place in game 61 of the 70-game schedule when they beat the Toronto Maple Leafs 5-0 in Chicago on March 12, 1967. Five days later, the Black Hawks arrived in Toronto ahead of their March 18 return date against the Maple Leafs. They discovered a large crate in their dressing room containing the Prince of Wales Trophy.

They pushed the crate into the washroom and, as Red Burnett wrote in The Toronto Star, “they tried to open it and to have a look at the trophy the Hawks finally captured after 41 years of sweat and tears. It was locked!”

“Things never seem to change,” said Chicago coach Billy Reay. “Instead of these trophies catching up to you at home, you bump into them on the road and have to lug them with you. I remember the year my Buffalo team won the AHL title, we played one of our last games in Providence. They had won the cup the year before and tried to save freight costs by having us pack it in our already overcrowded bus. I refused. But this time I’ll suffer. We want to make sure that hunk of silver finally hits Chicago. They’ve waited a long time to see it.”

So, the Black Hawks lugged the boxed-up trophy home after a 9–5 loss to Toronto on Saturday night and arranged for their own presentation ceremony at The Chicago Stadium on Sunday, March 19, prior to their game against the Canadiens. Though there’s no actual mention in any story as to whether or not the players ever did touch the trophy, there was certainly no concern about celebrating it!

Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1967.

After their 4-4 tie with Montreal, the Chicago players departed for the Bismarck Hotel, where they held an official championship celebration. The next day, they were paraded from Wacker Drive and State Street to City Hall, where Mayor Richard J. Daley presented each player with a Certificate of Merit and captain Pierre Pilote took possession of the five-foot tall, gold-tinged Mayor Daley Trophy.

No doubt Chicago hockey fans were pleased by their team’s first place finish, but it all went for naught when the Black Hawks were upset in the first round of the playoffs by the Maple Leafs, who went on to win the Stanley Cup in 1967. Toronto hasn’t won the Stanley Cup since … so if there really is some bad luck attached to the Prince of Wales Trophy, it obviously stuck to the wrong team that year!

May 18, 2016

Black Cats For Luck?

As many of you will know, before the opening game of their second-round series with the Nashville Predators a couple of weeks ago, a black cat emerged from the San Jose Sharks bench and ran across the ice. She was rescued under the stands and taken to the local Humane Society where she was dubbed Jo Paw-velski after Sharks captain Joe Pavelski. If you haven’t seen it, you can check out the clip on YouTube. Jo has now found a permanent home, having been recently adopted by a family (fittingly enough) on Friday, May 13!

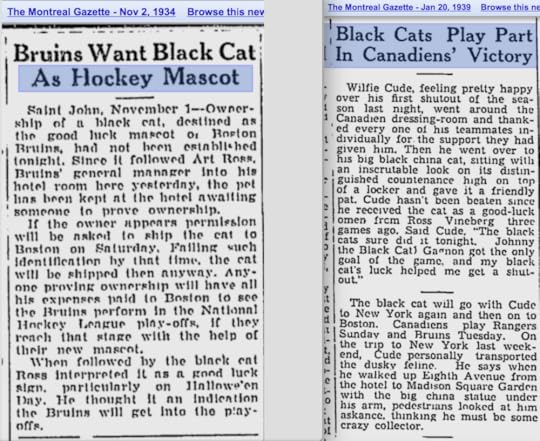

With the little black cat as their unofficial mascot, San Jose got past Nashville in seven games. The Sharks are now tied 1-1 in the Western Conference Final with St. Louis after a big win last night. Who knows how much of this can be attributed to their feline friend, but it turns out that black cats have a long history as good luck charms in the NHL.

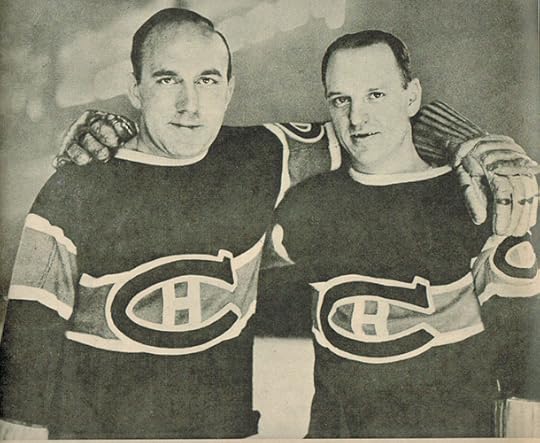

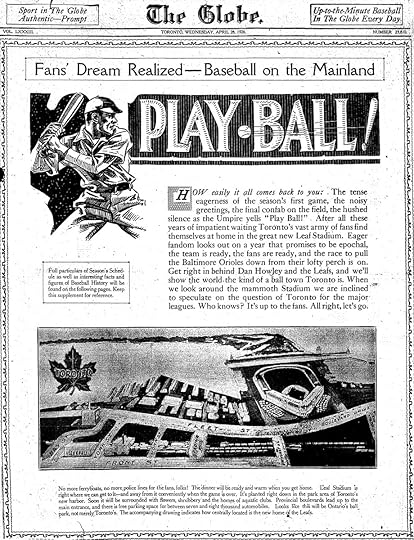

Some of you reading this will know of Johnny Gagnon, who spent most of his ten-year career in the NHL from 1930 to 1940 playing with the Montreal Canadiens. He was known as “Black Cat,” supposedly because of his jet-black hair and piercing eyes – or perhaps because of his cat-like reflexes. Gagnon spent the early part of his career playing right wing on a line with Howie Morenz and Aurele Joliat, and actually scored the first goal in the 2-0 win I wrote about last week that gave the Canadiens their second of back-to-back Stanley Cup wins in 1931.

Some of you reading this will know of Johnny Gagnon, who spent most of his ten-year career in the NHL from 1930 to 1940 playing with the Montreal Canadiens. He was known as “Black Cat,” supposedly because of his jet-black hair and piercing eyes – or perhaps because of his cat-like reflexes. Gagnon spent the early part of his career playing right wing on a line with Howie Morenz and Aurele Joliat, and actually scored the first goal in the 2-0 win I wrote about last week that gave the Canadiens their second of back-to-back Stanley Cup wins in 1931.

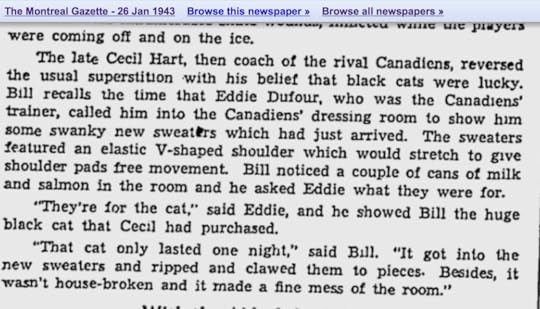

Interestingly, Gagnon’s coach in Montreal – Cecil Hart – had some sort of thing for black cats, and it had proved lucky for the Canadiens in the playoffs in 1930.

According to a story in the Montreal Gazette on April 1, 1930, Hart had come across a large black cat under the stands at the Montreal Forum before the Canadiens and New York Rangers headed out for a fourth period of overtime a few nights before. Hart patted the cat for luck and Gus Rivers scored a few minutes later to give the Canadiens a 2-1 victory.

Two nights later, Hart chanced upon a black cat again prior to the game at Madison Square Garden, and this time Montreal scored a 2-0 victory to take the series and advance to the Stanley Cup Final against the Boston Bruins. “Two of the supporters accompanying the team,” said Gazette writer L.S.B. Shapiro, “decided to go ahead with the black cat idea, and now Cecil Hart carries a miniature one in his club bag.”

Whether or not the cats made a difference, the Canadiens went on to score a surprising Stanley Cup sweep of a Bruins team that had been one of the greatest in hockey history during the 1929-30 season.

And Hart was apparently not alone with his black cat fetish, as these stories attest:

But it seems that not all of Cecil Hart’s cat stories worked out so well, as this note in Dink Carroll’s column in the Gazette relates:

May 11, 2016

The Mighty Atom and The Stratford Streak

Last week, in my story about the first nationwide hockey broadcasts, I mentioned there would be more this week about the 1931 Stanley Cup Final. The Canadiens won the Cup that year in a tight series with the Chicago Black Hawks. It was Montreal’s second championship in a row.

The Canadiens were coming off a tough first-round matchup with the Boston Bruins. That best-of-five series went the distance with three of the games going into overtime. Montreal opened the Stanley Cup Final in Chicago on April 3, 1931, winning the first game 2-1 but dropping a double-overtime decision by the same score two nights later. This best-of-five set then shifted to Montreal for the remaining games, and Chicago took game three 3-2 in triple overtime. Montreal stayed alive with a 4-2 win in game four, setting the stage for the finale on April 14.

In a short feature covering several topics in the March 31, 1962, issues of Canada’s Weekend Magazine, Canadiens legend Aurele Joliat reminisced about the 1931 Stanley Cup Final with sportswriter Andy O’Brien. Joliat’s longtime linemate and great friend Howie Morenz had been the leading scoring in the NHL that season with 51 points (28 goals, 23 assists) while playing in 39 of the season’s 44 games. Through nine playoff games, he’d picked up four assists, but had yet to score a single goal. However, with the Canadiens clinging to a 1-0 lead late in game five, “It was Morenz who scored the goal that broke it up.”

Aurele Joliat (right) kept this picture of him and Howie Morenz in the den of his

Ottawa home. There is no photo credit in the Weekend Magazine story.

“Morenz had rushed away from us with the puck down center ice and was checked at the defence,” Joliat recalled. “Some Chicago forward picked it up on the gallop and I checked him at center. I had only taken two strides when I heard ‘Joliat!’ screamed at me from the right wing. It was Morenz who had raced back on my left wing, whirled around behind me and was now under full steam down the right. I gave him a pass. He took it at full speed and went clean through the Hawk defence to beat goalie Charlie Gardner.”

Here’s how Canadian Press staff writer H.M. Peters described the goal at the time:

“Howie Morenz had been held scoreless for nine consecutive playoff games. It was unheard of in his career as a professional. Suddenly, he grabbed a puck at center ice and whirled his way around the left defence, hesitating until he was sure of the shot and hammered it home true.

“It was some minutes before play could be resumed as the fans showered the ice with programs, newspapers and even hats.

“Only four minutes were left and the Canadien supporters’ song of victory, ‘Les Canadiens Sont La,’ was being roared from the rush end.”

In Andy O’Brien’s story, Aurele Joliat recalled that he was paid $1,500 as a rookie in 1922-23 and that Morenz earned just $1,200 when he joined the Canadiens the next year. (More modern sources have Morenz earning $2,500 or $3,500 as a rookie.) Joliat was 60 years old in the spring of 1962 and was working in the information wicket for the CN Railway at Ottawa’s Union Station. He was wistful, O’Brien writes, about the average NHL player being paid $12,500 in 1962.

“Modern hockey is so fast I can hardly follow it at times,” said Joliat, “but nobody I’ve seen since Howie could combine so much skill with such tremendous speed.”

May 3, 2016

Looking Back at Listening In

A while ago on this web site, I mentioned my interest in the early history of hockey broadcasts on the radio. Mostly, that relates to the very first broadcasts in 1923 and trying to uncover if there’s anything earlier than the known broadcasts from Toronto that February. Well, this doesn’t pertain to that, but I did find it interesting.

With ratings down all season for hockey broadcasts on Rogers Sportsnet, and as the playoff ratings are said to be taking a huge hit with no Canadian teams involved, let’s take a look back to when national hockey broadcasts began.

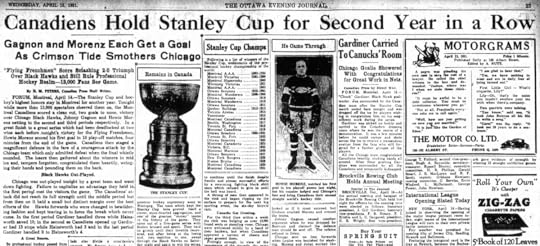

This picture of Foster Hewitt appeared in a story in

The Sunday Times-Signal of Zanesville, Ohio, on September 2, 1928.

The first national hockey broadcasts in Canada have long been attributed to the nationwide hookup for the opening game from Maple Leaf Gardens on November 12, 1931. Some sources point to the General Motors Saturday night broadcasts that began in January of 1933 and were later taken over by Imperial Oil. These were the roots of Hockey Night in Canada.

Turns out, however, that the first national broadcasts (much like the earliest broadcasts in 1923) were actually made from the Arena Gardens on Mutual Street. Fittingly, it was a game between the Toronto Maple Leafs and the Montreal Canadiens. The date was January 17, 1929 – almost three years before the opening of Maple Leaf Gardens.

Ironically, given radio station CFCA was owned by the Toronto Star, I recently stumbled across word of this in the rival Globe. On January 8, 1929, Globe sportswriter Bert Perry noted at the end of his column:

“When the Montreal Canadiens make their second visit of the season here on Jan. 17 the game will be broadcast over the Canadian National Broadcasting Company’s chain of stations from Halifax to Vancouver. It will be the first time that a Dominion-wide hook-up on a hockey game has been tried in Canada. Some fifteen Canadian stations will relay the play-by-play account to every corner of the country. The fans in Halifax, Edmonton and Vancouver will get the details right from the Arena Gardens as clearly as Toronto listeners-in.”

When W.A. Hewitt – father of Foster – mentioned the story a week later in the Toronto Star, he had more (and slightly different) details:

“A joint broadcast of unusual interest to Canadian hockey fans will be held on Thursday night of this week when the Maple Leafs-Canadien NHL game will be sent out on the air from Arena Gardens, Toronto. The broadcast is to be given under the joint auspices of the Toronto Daily Star and the Canadian National Railways over Stations CFCA of the Toronto Daily Star at Toronto and the Canadian National Railway’s chain of stations at Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto and Winnipeg with CJGX, the Winnipeg Grain Exchange station at Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Foster Hewitt will be at the microphone. This will be the first time that a hockey broadcast of such magnitude has been attempted and the hook-up will interest hockey and radio fans in all parts of Canada.”

Foster Hewitt began his nationwide broadcast at 9 o’clock in Toronto.

The Leafs and Canadiens ended up tied after three periods, and when 10 minutes of overtime settled nothing, they skated off with a 1–1 tie. In one story on the sports pages of the Star, the game was described as “dull for the most part, with both goals coming in the first four minutes of the second period.” (Danny Cox, assisted by Hap Day, scored for Toronto; Sylvio Mantha for Montreal. Howie Morenz was out with an injury.) A story just after the Radio page noted that Hewitt, “described the game in a graphic way.”

By the end of the 1930-31 hockey season (still seven months prior to the opening of Maple Leaf Gardens), Foster Hewitt was calling all the most important games on the radio from coast to cost. He called the Memorial Cup finals between the Elmwood Millionaires (Manitoba) and the Ottawa Primroses on March 23, 25 and 27; the Allan Cup games between the Winnipeg Hockey Club and the Hamilton Tigers on March 31 and April 2; and the last three games of the Stanley Cup Final on April 9, 11 and 14 as the Canadiens beat the Black Hawks in five games. (More on the finale of that series next week.)

Writing in the Toronto Star on April 15, 1931, Foster’s father had this to say:

“The hockey season which ended last night with a coast-to-coast network broadcast of the Stanley Cup final was another triumph for CFCA (Toronto Star). Over 50 hockey games were broadcast during the season by Foster Hewitt and these included all the Maple Leaf Hockey Club sheduled games, the finals for the OHA championships in all series, the Allan Cup finals at Winnipeg, the Memorial Cup finals at Toronto and Ottawa and the Stanley Cup finals at Montreal. Foster Hewitt’s voice is now as familiar in Vancouver and Halifax as it is in Toronto and throughout the province of Ontario.”

And to show that W.A. Hewitt wasn’t just being a boastful father, consider these stories in the Toronto Star of April 21, 1931, picked up from other Canadian cities:

April 27, 2016

90 Years Ago This Week…

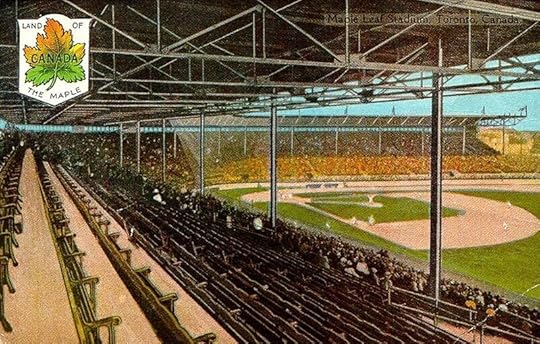

For a building I never set foot in (the team played its last game there shortly before I turned four) and can’t even remember seeing (it was torn down just a few months later), Maple Leaf Stadium has had a big impact on my life. It’s the place that helped create the love of sports in my mother and father (and my aunts, uncles, and older cousins) that’s been passed down to me and my brothers and on to a new generation.

Certainly my parents saw a lot more baseball games at Maple Leaf Stadium than they ever saw hockey games at Maple Leaf Gardens. I know my father’s childhood heroes were Teeder Kennedy and Max Bentley, but he was a big baseball fan too. And my mother LOVED the baseball Maple Leafs (in particular Ed Stevens during the mid 1950s). She still loves baseball and she’s the reason we still have the season’s tickets to the Blue Jays we’ve had since the moment they went on sale before the first season in 1977.

My father, grandfather, and aunt in the mid 1940s. I’ve been told this

is Maple Leaf Stadium (but I think it might be Varsity Stadium).

The Blue Jays are celebrating their 40th season this year, but it was 90 years ago this week that Maple Leaf Stadium opened. Previously (since 1897), the baseball Maple Leafs had played at Hanlan’s Point on the Toronto Islands. Babe Ruth hit his first pro home run there, but it wasn’t the easiest place to get to.

“After years of hope deferred,” wrote Toronto Globe Sports Editor Frederick Wilson on September 5, 1925, “the baseball fans of Toronto are to see their dreams come true, and next season the Leafs will play their games in a magnificent $300,000 stadium on the mainland at the foot of Bathurst Street.” The geographic center of the city at the time, explained Wilson, was “at a point on Harbord Street, about one hundred feet west of Bathurst,” so – forgive me if you don’t know Toronto geography! – the new site was certainly more accessible than the Island.

This was the front page of an 18-page supplement The Globe ran on April 28, 1926.

Work on the grounds at Bathurst and Fleet Street (very close to what is now the Tip Top Tailor lofts near the Canadian National Exhibition grounds) began in October of 1925, and construction on the stadium began in earnest on December 2. Though it wouldn’t be completely finished at the time, Opening Day was scheduled for April 28, 1926, after the team had spent the first two weeks of the season on the road.

Sadly, it seems, the weather has not been very cooperative for the opening of Toronto baseball stadiums. The Blue Jays played at Exhibition Stadium on April 7, 1977, despite snow and freezing temperatures, and while the elements weren’t a factor in the first game at SkyDome on June 5, 1989, it was pouring rain during the official opening gala two nights earlier when organizers insisted on opening the roof anyway!

Wikipedia claims this photo is in the public domain!

Credit is to the Bibliotheque et Archives nationals du Quebec, P547,S1,SS1,SSS8,D1.

Many dignitaries were in Toronto for the 1926 opener, including baseball commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who was given a pregame tour of the facility. “Absolutely nothing forgotten over overlooked,” Frederick Wilson quoted him as saying. “[It’s] as near perfection as it is possible to have a baseball park.” But unlike the SkyDome/Rogers Centre, it didn’t have a roof! Cold temperatures and heavy rains postponed the opener.

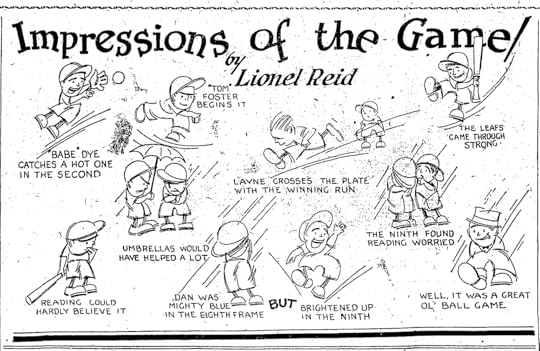

Torontonians of a certain age will recall Joe Crysdale on the radio, broadcasting the home games from Maple Leaf Stadium and re-creating them with telegraphed reports and sound effects when the team was on the road. For the opener in 1926, Foster Hewitt was set to call the game on Toronto Star radio station CFCA. It’s unclear whether he was there or not a day later, on April 29, 1926, when they got the game in despite a constant drizzle. Only 12,781 fans were on hand as the Maple Leafs fell behind Reading 5-0 heading into the bottom of the ninth. Those who stuck around where rewarded when Toronto rallied for five runs to tie the score, and then won the game 6-5 on a squeeze play in the bottom of the tenth. (The game, by the way, was complete in 2 hours and 15 minutes!)

From The Globe , Toronto, April 30, 1926.

The come-from-behind victory was a good omen. Baltimore had won the International League pennant every year from 1919 to 1925, but in 1926, Toronto had a record of 109-57 to take the league title. They then swept five straight games from Louisville of the American Association to win the best-of-nine Junior World Series. (Oh, and the weather was much nicer for the opener in 1927, and a large crowd was on hand to honor the champions, as this newsreel film shows.)

When it was built in 1925-26, state-of-the-art Maple Leaf Stadium was constructed with an eye towards housing a future Major League team. By the 1960s, Jack Kent Cooke – who then owned the baseball Maple Leafs – felt a brand new park was needed to attract the Majors, but he couldn’t convince City Council to cover the costs. The end was near. Attendance was awful despite championship seasons in 1965 and 1966, and the team was sold and transferred to Louisville after the 1967 season. The Stadium was torn down in the spring of 1968. Only the memories remain – even for those of us who inherited them.

April 19, 2016

A Tale of Tom Phillips

I don’t really have a good explanation for why I like the early history of hockey as much as I do. I still watch plenty of the current game, but as I often say to people when they ask me, I can tell you with a lot more authority why the Kenora Thistles won the Stanley Cup in 1907 than I can tell you why I think a team might win it this year.

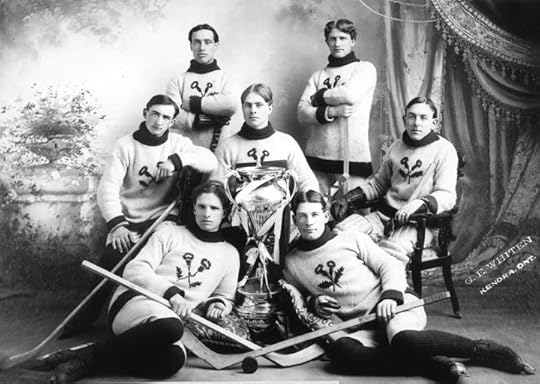

Thistles captain Tom Phillips (who I’ve written about extensively for the Society for International Hockey Research and mentioned a couple of times on this site) is one of a handful of early era Hall of Famers (along with Art Ross, Frank & Lester Patrick, Cyclone Taylor, Newsy Lalonde, Joe Hall and Fred Whitcroft) that I find fascinating.

Tommy Phillips reclines to the right of the huge trophy symbolizing the senior championship of the Manitoba Hockey League, which the Kenora Thistles won for the

second of three straight seasons in 1905-06.

Tommy Phillips was the Sidney Crosby of his day. In his era, he was considered one of the top two players in hockey. If you were from the West, you’d likely pick him; while Easterners were more partial to . McGee was a goal-scoring machine with the Ottawa “Silver Seven” who was famously blind (or at least had his vision impaired) in one eye. Turns out, Tommy Phillips was playing under a pretty severe handicap too.

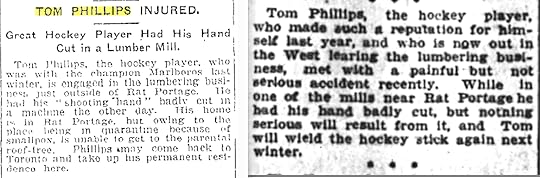

Articles from the Toronto Star on August 4, 1904 and the Ottawa Journal one week later.

Several years ago, I came across the Toronto Star newspaper clipping above claiming that Phillips had injured his hand while working in a lumber mill near his hometown during the summer of 1904. Recently, I went searching for more stories about this, and discovered a couple of clips that make the injury sound a lot more serious than just a bad cut. It seems Phillips had actually lost parts of three fingers on his right hand.

Articles from the Winnipeg Morning Telegram and Winnipeg Tribune on November 29, 1904.

Look again at the team picture above, and then have a look at the (slightly blurry) blow up below. Clearly, there’s something up with Phillips’ right hand.

There appears to be a strap leading to what is either a protective cover or some sort of artificial right index finger. His pinky as well as the finger next to it (which certainly seems to be abnormally short) both look to be similarly protected or replaced.

Unlike Hall of Fame baseball pitcher Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown of the same era – who had his right hand mangled in farm machine as a youth but learned to grip a baseball in such a way that it gave him an exceptional curve ball – it’s hard to believe that Tom Phillips’ accident gave him any sort of physical advantage.

Yet given that had the best years of his career from 1904-05 through 1907-08, he was clearly able to perform at an extremely high level despite his injury. He may not have been Bobby Orr on wounded knees, or Mario Lemieux beating cancer, or Sidney Crosby coming back from a concussion, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

April 12, 2016

Nobody’s Perfect…

I was at the Blue Jays’ home opener on Friday. As I no longer live in Toronto, I don’t get to many games anymore, but Opening Day is something special. Forget about Christmas, early April, when spring is supposed to be springing, baseball is getting started, and the hockey playoffs are here… THAT’S the most wonderful time of the year!

The Zweig boys, with their mother/grandmother on Opening Day. For Joyce, Jonathan

and me, this one made us 40 for 40 … but I’m the only one who was also at the

makeup game for the rained out opener in 1980.

Baseball, of course, is a game bound by tradition. And I am a big fan of sports history. But while I admit that I’ve been known to complain that “the game [ANY game] was better when I was younger,” I wouldn’t say I’m truly a traditionalist. I don’t mind modern innovations … but I have to admit that instant replay irks me.

It’s long been called “a game of inches” but now, it seems, that baseball is “a game of painful exactitude which we can measure in fractions of seconds … if we get a good shot in super slo-mo that we can blow up large enough.”

Yes, it’s pretty hard to argue against “getting the call right,” but as others have argued before me, there are rules, and then there is the spirit of the rule. Of course a runner can’t wander off the base with impunity, but is he really supposed to be out if his foot pops off the bag for a fraction of a second? And I really hate the way, in baseball, they linger and waste time while the clubhouse pre-checks the replays first. If you want to challenge a play, I think you should have to challenge it based on what you think you actually saw! After all, that’s how the umpire has to call it.

As I said, it’s hard to argue against getting the call right — and, of course, Armando Galarraga SHOULD have had that perfect game in 2010, and Derek Jeter probably should have been out for fan interference on that Jeffrey Maier home run in 1996. Still, what can I say? The delays (and the fact that they still don’t seem to get the call right every time!) just bother me.

I’m not really trying to argue that we should do away with instant replay … but then again, no one else in a game gets a second chance if they screw up! And once upon a time, it was clear that people believed it was ridiculous to allow TV cameras to make the final call. Of course, this was a long time ago…

Ten years before the first Blue Jays opener, in the last game of the NHL regular season in 1967, Chicago’s Stan Mikita picked up two assists to finish the season as the scoring leader with 97 points. That happened to tie teammate Bobby Hull’s single-season scoring record … but Mikita thought he’d earned a third assist in the Black Hawks’ finale against the New York Rangers.

Stan Fischler, writing in a special to the Toronto Star on April 3, 1967, reported that: “[Black Hawks coach] Billy Reay was bubbling with anger in the Chicago dressing room… Reay was furious over the confusion surrounding Stan Mikita’s point allotment in the game at Madison Square Garden. Officially, Mikita got two assists … [b]ut unofficially, the belief was that Mikita deserved another assist on Doug Mohns’ goal at 2:14 of the third period.”

Official scorer Lamie Crovat promised, “I’m going to study a video-tape of the goal in the Madison Square Garden office on Monday and make a final determination.” Reay snapped back, wondering, “Why doesn’t he (Crovat) keep his eyes on the ice instead of the tape?” And it soon became clear that the NHL had no interest in what a video review might show.

Writing in The Star on Tuesday, April 4, the dean of Canadian sportswriters Milt Dunnell pointed out: “Conn Smythe used to say the customers had a right to know the result when they left the rink. That’s why he never would permit a protest of a Leaf hockey game. Contests were for the ice – not the committee room.”

“Clarence Campbell, the NHL president,” Dunnell said, “applied the same principle to Stan Mikita’s claim of a third assist in Sunday afternoon’s game at New York. What Campbell said, in effect, is that he doesn’t care what video tapes of the game prove.”

So, Mikita didn’t get his extra point, nor a new scoring record … and Dunnell clearly believed this was the right decision. “If [Lamie Crovat] even hinted he might change his decision in the event the film showed Mikita’s claim was justified, he exceeded his authority.”

And Dunnell wasn’t finished yet. “The video tape has no official status in the NHL, nor in football, baseball – any team sport you can mention.” He adds that when Stafford Smythe had a TV monitor installed near the penalty box at Maple Leaf Gardens “for the possible guidance of officials,” the referees got rid of it “by refusing to look at it.”

“The day referees, umpires, linesmen, and judges of play consent to be influenced by the eye in the sky, they will be as dead as the dodo bird,” Dunnell argued. “Hockey coaches being the mourners which, as a group, they are, would challenge every decision of the officials. Any contest that was completed in less than five hours would be a rarity.”

But, of course, times change…

April 6, 2016

A Future NHLer at 3 1/2

Famous as he is for all the NHL records he set, Wayne Gretzky is almost as famous for the fact that he’s been famous since he was 10 years old. Sidney Crosby is said to have given his first newspaper interview when he was just seven.

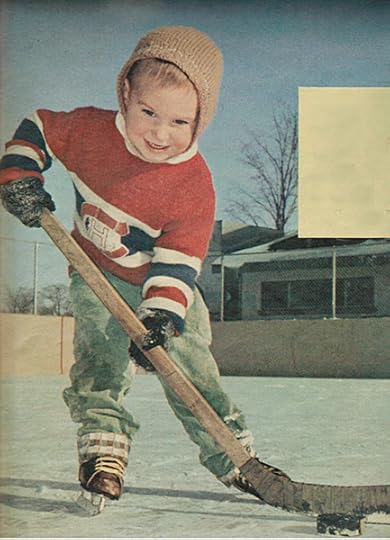

Gretzky began skating at the age of two, and Crosby at three. The backyard rink in Brantford, Ontario, where Gretzky practiced as he grew up, and the basement dryer Crosby would shoot at in the family home in Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia, are both a part of hockey lore now … but neither of them was featured on the cover of a Canadian national magazine when they were only 3 1/2. So, does anyone recognize this future NHL player?

To help me pass the time during my recent recuperation, my wife Barbara bought up a whole bunch of Weekend Magazine issues dating from 1959 to 1963 at a local antiques/collectibles store. They’re pretty great! The little guy in question appeared on the cover on February 24, 1962.

Growing up in Kingston, Ontario, his father was a Senior A hockey player and youth coach from Toronto and his mother was a strong skater from Montreal. He began attending his father’s games at the age of three months, and by his first birthday in August of 1959, he was “chasing around the living room with a cut-down hockey stick,” says writer Bill Trent in the story that appeared on page 23 of the magazine.

Come the winter of 1959–60, the toddler took to the ice on bobskates. The following winter, when he was 2 1/2, he was skating on tube skates. When the weather didn’t permit for going outside, there was a rink in the basement. “Well, it’s really a make-believe rink,” explained Trent, “with linoleum for ice and a packing case for a players bench. And [boy’s name] has to be careful not to go banging up against the washing machine. But when he faces off at the blue line, it’s almost as good as the real thing.”

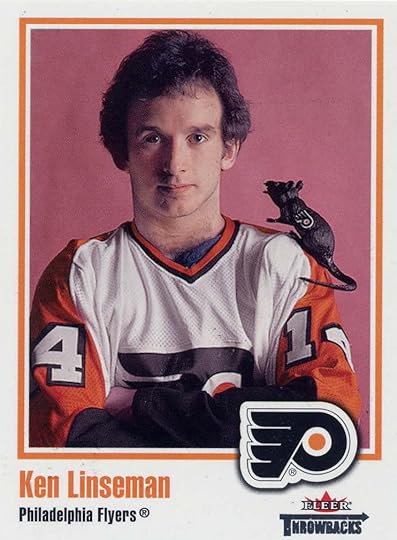

So, who is it? Check out the hockey card below…

Ken Linseman played 14 seasons in the NHL with Philadelphia, Edmonton, Boston and Toronto from 1978 to 1992. He was no Wayne Gretzky or Sidney Crosby, but “The Rat” (who was called that, it seems, in equal parts for his facial features, his hunched-forward skating style, and his ability to agitate) had some pretty good offensive seasons. He had a career total of 256 goals and 551 assists (807 points) in 860 regular-season games and won the Stanley Cup with the Oilers in 1984.

March 30, 2016

Stanley Cup Anniversaries: 2016

As we near the end of a regular season that will see no Canadian teams in the playoffs for just the second time in NHL history (the first being 1969-70, when only two of 12 NHL teams were based in Canada — see today’s Toronto Star), it’s somewhat ironic that today marks the 100th anniversary of the first of a record 24 Stanley Cup victories for the Montreal Canadiens – against the first team to compete for the trophy from the United States.

On March 30, 1916, the Canadiens scored a 2-1 victory over the Portland Rosebuds on a late goal by Goldie Prodger in the fifth and final game of the best-of-five series between the champions of the National Hockey Association and the champs from the Pacific Coast Hockey Association.

The Montreal Daily Mail, March 31, 1916. Page 8.

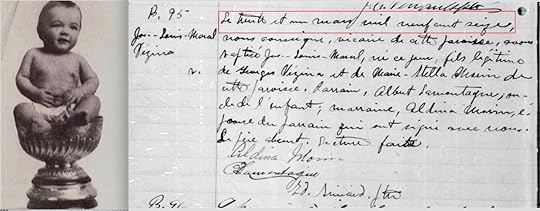

It has long been said that the wife of Canadiens goaltending legend Georges Vezina gave birth to a son that same night, whom the Vezinas named Marcel Stanley in honour of the Cup. In truth, the boy was born the following night, March 31, 1916, and was formally christened Joseph Louis Marcel Vezina – although it does appear to be true that the family called him Marcel Stanley.

The birth record for Joseph Louis Marcel “Stanley” Vezina states in French

that he was born on le trente et un mars mil neuf cent seize.

It won’t happen this year, but years ending in ‘6’ have traditionally been good ones for the Canadiens and for other teams from Montreal. Here’s a quick look at the last 120 years of Stanley Cup competition…

1896: I’ve often argued that this is the year that made the Stanley Cup. Until 1896, the trophy was better known for off-ice squabbles than anything else. But the interest was clearly in what happened on the ice when the Winnipeg Victorias defeated the Montreal Victorias on February 14, followed by the Montreal team winning back the trophy in a rematch on December 30. This made the Stanley Cup the national institution it’s been ever since.

1906: The Montreal Wanderers ended the Stanley Cup reign of the Ottawa “Silver Seven” … but just barely. After winning game one 9-1, the Wanderers gave back their eight-goal lead in game two before Lester Patrick scored twice late in the game to give Montreal a 12-10 win in the total-goals series.

1926: In just their second year in the NHL, the Montreal Maroons won the league title behind the scoring exploits of Nels Stewart and the goaltending of Clint Benedict. The Maroons then defeated the defending champion Victoria Cougars of the Western Hockey League to win the Stanley Cup. Victoria is the last non-NHL team to have played for the Stanley Cup.

1936: The Detroit Red Wings became the last of the so-called “Original Six” NHL teams to win the Stanley Cup. “The boys were good enough to win this year,” said coach and general manager Jack Adams, “and they’ll be better next season.” Adams was right, as the Red Wings won again in 1937.

1946: Having won it in 1944 to end a 13-year drought dating back to 1931 (a time known to fans of the team as The Grande Noirceur — The Great Darkness, which also refers to the Quebec government policies of 1936 to 1959), the Canadiens won the Stanley Cup for the second time in three years on Elmer Lach’s overtime goal to beat the Bruins in game five of the Final.

1956: After losing to Detroit two years in a row, the Canadiens downed the Red Wings in five games to win the Stanley Cup; the first of a record five straight championships through 1960. It’s often said that the disappointing end of the 1954-55 season, when the Richard Riot saw Maurice Richard suspended for the entire playoffs, helped to launch this great dynasty.

1966: The Canadiens again, defeating the Red Wings in six games to win their second Stanley Cup in a row. Henri Richard scored the winner in overtime after being hauled to the ice and sliding into the net with the puck underneath him. Detroit goalie Roger Crozier insisted that Richard had swiped the puck in illegally with his glove.

1976: “There was a great sense of quest that season,” writes Ken Dryden in his hockey classic The Game. The Canadiens were determined to end the Philadelphia Flyers’ two-year championship run of goon hockey, and swept them in four straight in the Stanley Cup Final. It was the first of four straight championships for Montreal.

1986: In one of the most surprising championships of their record 24, a Montreal Canadiens team featuring all sort of rookies – including Conn Smythe Trophy winner Patrick Roy – defeated the Calgary Flames in five games. The Flames were the first Calgary team to play for the Stanley Cup since the Calgary Tigers of the Western Canada Hockey League, who were defeated by the Canadiens back in 1924.

1996: After being traded by the Canadiens to the Avalanche, Patrick Roy helped Colorado win the Stanley Cup in its first year in Denver after 16 seasons as the Quebec Nordiques. And consider this unusual fact: Colorado’s win over Florida that year marks the ONLY TIME in NHL history that both teams in the Final had never played for the Stanley Cup before.

2006: The Edmonton Oilers barely reached the playoffs this season, but then went all the way to the Final and pushed Carolina to seven games before the Hurricanes won the Stanley Cup. Another odd fact: When neither team made the playoffs in 2007, it marked the first time in NHL history that both Finalists failed to qualify for the playoffs the following year.