Eric Zweig's Blog, page 18

January 17, 2017

Rock and a Hard Place…

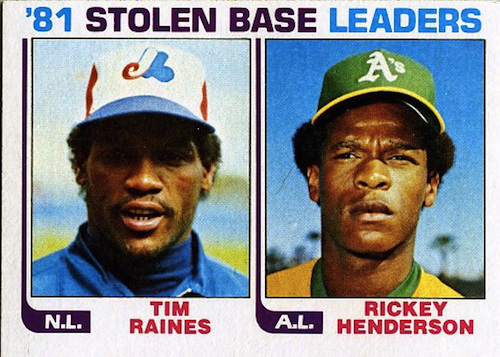

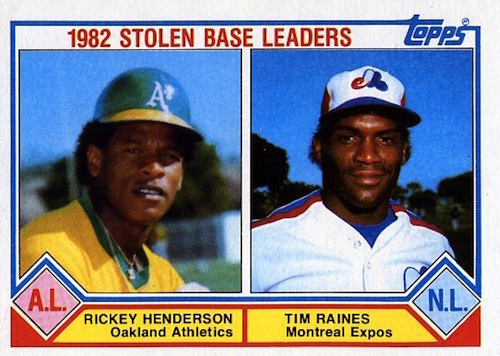

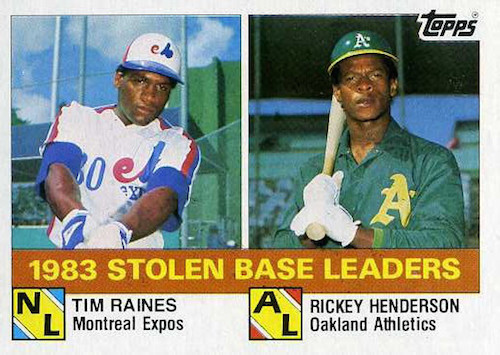

Right up front, let me say that I hope Tim Raines makes it on Wednesday when this year’s election results for the Baseball Hall of Fame are announced. All the early indications are that in his tenth and final year on the ballot (players used to get 15 years, but that’s no longer the case), Raines will finally top the 75 percent of votes needed for induction.

It’s a strange thing. After waiting the required five years to qualify for the Hall of Fame ballot, what suddenly makes a player worthy after being forced to wait another 10 years? Many are saying it’s a triumph of the new voting rules that have phased out older sportswriters who are no longer actively covering the game. The younger writers are more open to modern statistical interpretations.

Gary Carter, Andre Dawson, Steve Rogers, Tim Raines and Al Oliver at the 1982

All-Star Game in Montreal. Raines was only 5’8″ and 160 pounds, but his

solid physique earned him the nickname “Rock” at an Expos rookie camp.

For a player like Tim Raines, who didn’t reach the big milestones such as 3,000 hits, younger voters are more likely to be impressed by the fact that when Raines’ hit total of 2,605 is combined with his 1,330 walks, he actually reached base more often (3,935 to 3,931) than eight-time National League batting champion Tony Gwynn. (Gwynn’s lifetime batting average was .338 to Raines’ .294, but his on-base percentage is .388 to Raines’ .385) . And though Raines’ career total of 808 steals is well behind all-time leader Rickey Henderson’s 1,406, the fact that Raines was caught only 146 times to Henderson’s 335 means Raines’ success rate of 84.7 percent is better than Henderson’s (80.8). It’s also better than the only other players from the 20th Century who had more steals than Raines: Lou Brock (938 / 75.3%) and Ty Cobb (897 / incomplete data).

In the New York Post recently, baseball writer and Hall of Fame voter Ken Davidoff said, “Raines’ admittance, if it happens, would serve as a triumph of facts and statistics over emotions and memories.” But, as Richard Griffin in the Toronto Star has written (and I’m paraphrasing), “if all you did was feed the numbers into a computer, it would be easy to decide who makes it in.” Obviously, statistics play a huge part in this, but I, for one, would hate to see memory discounted entirely.

For example, I know that Jack Morris didn’t put up the career numbers of recent Hall of Fame pitching inductees like Pedro Martinez, Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine and John Smoltz. But I watched him pitch his whole career; hating him as a Tiger, impressed by his one year as a Twin, and then amazed by his 1992 season in Toronto. Yes, he had a 4.04 ERA that year, but he was every bit as good as his 21-6 record indicates. When he needed to shut you down, he did. His complete-game, four-hitter 4-0 win over Boston on June 11, 1992, when he outpitched Roger Clemens (and yes, I remember it well … but I had to look up the date!) was a masterpiece. Though he never received more than 67 percent of the vote in his 15 years on the ballot between 2000 and 2014, for me, Jack Morris is a Hall of Famer.

As for Tim Raines, my thoughts are this… In the first 13 years of his career (basically 11 full seasons) with the Expos, he was definitely a Hall of Fame-calibre player. He was the kind of guy, like Roberto Alomar, that when he was at the plate, you expected something good to happen. But I’m not sure fans of the teams he spent his final 10 years with (mainly the Chicago White Sox and the New York Yankees) felt the same way. Sure, he was a good teammate and a good role player, but as a Blue Jays fan in those years, I don’t recall having any fear of him coming to the plate like the excitement I’d felt when he was batting for the Expos … although he did put up some pretty good numbers against Toronto in the 1993 American League Championship Series.

All in all, I’d say for Tim Raines the good years outweigh the mediocre ones, but this has to be a big reason why his candidacy has gone right down to the wire. Another reason, so I’ve read, is that some writers have refused to vote for him because of his cocaine suspension. To me, that’s ridiculous. How can you hold it against someone who served his time, kicked the habit, and never relapsed?

Which brings us to Roger Clemens, Barry Bonds and others of the steroid era. If I had a vote, I’d vote for them.

Do I wish there was no such thing as drugs in sports? Yes. Still, I think the world has been pretty hypocritical about performance enhancing drugs. Athletes have been using whatever they could to get an advantage for a very long time. Caffeine to get up; nicotine to calm down; oxygen; cold medications; amphetamines. What is it that makes a guy a hero for taking a shot of cortisone and playing through the pain versus a guy taking a shot of something else?

Yes, I know it’s illegal to use one without a prescription. So, that’s where we draw the line? But what makes something a medical miracle and something else an abomination? Why isn’t it cheating to take a tendon from a cadaver, or another part of your own body, and sew it into a pitcher’s elbow? What if doctors could figure out a way to do the same thing with muscles? Would THAT be cheating? We certainly don’t say pitchers can’t have Tommy John surgery because is wasn’t available in the old days. We don’t say today’s hockey players can’t have their knees scoped because they didn’t have that medical advancement in Bobby Orr’s day.

We’re pretty quick to jump on professional athletes who we perceive as not trying hard enough. But we seem to be even harder on the athletes who felt they had to take drugs to be the best they could be. What if Bobby Orr could have taken a shot of something and it saved his career? Would we look back on it as cheating … or would we see it as one of the greatest athletes of all time doing whatever it took to stay at the top of his game?

January 10, 2017

The Oldest NHL Player

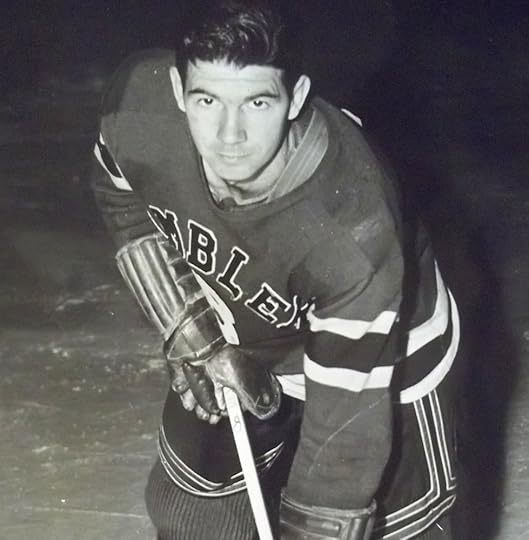

With the death of 98-year-old Milt Schmidt on January 4, 2017, the distinction of being the oldest living NHL player falls upon John (Chick) Webster. It was a possibility he had already discussed with his son, Rob. “He told me, ‘This is probably my best record,’” said Rob with a chuckle when we spoke on the phone last week.

Webster, who recently turned 96, was just being modest. Though he only played 14 games in the NHL back in 1949-50, and never scored a point, Webster (who earned the nickname Chick because of his fondness for Chiclets gum) had a remarkable, and long, career.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

John Webster was born in Toronto on November 3, 1920. “I don’t even think his parents knew that he and his brother [Don, who would play for the Maple Leafs in 1943-44] were serious about hockey until they reached juniors,” said Rob. After three years in the OHA with the Toronto Native Sons, Chick attended his first NHL training camp with the Boston Bruins in the fall of 1940. Not only did he meet Milt Schmidt at the camp in Hershey, Pennsylvania, he briefly replaced him during practice centering Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer when Schmidt hurt his ankle.

Writing in the Globe and Mail on October 28, 1940, Sports Editor Vern DeGeer notes that Webster, “made a fine impression on Art Ross.” Still, Webster expected to be sent back to Toronto to return to the Native Sons. However, having signed the C-Form that would bind him to Boston until they decided otherwise, Webster was sent by the Bruins to Baltimore of the Eastern Amateur Hockey League for the 1940-41 season.

Globe and Mail, October 28, 1940.

By the following year, regulations established during War time made it difficult for many Canadian men to cross the border. Webster remained in the Toronto area for the 1941-42 season, and soon enlisted with the Canadian army. He encountered Schmidt again in March of 1942 when Webster’s Camp Borden team lost an 11-2 decision to the Kraut Line’s Ottawa RCAF Flyers. “I don’t remember that,” Chick admitted to me, but he does recall hooking up with them all again for a game in England. “I had to borrow skates from the rink for that one,” he says.

Globe and Mail, March 9, 1942.

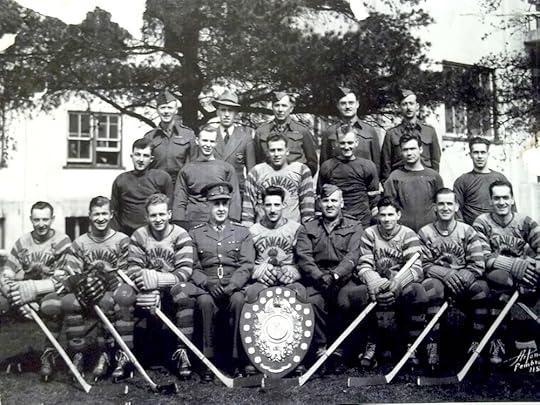

Before he was sent overseas, Webster spent the 1942-43 and 1943-44 seasons playing hockey for the Army with the Petawawa Grenades. “Turk Broda was our goalie,” he remembers. (The once and future Leafs great played with Petawawa in 1943-44.)

Army team at Camp Petawawa. Chick Webster is in the front row, third from the right.

Turk Broda is not present, so this is likely 1942-43. Courtesy of Rob Webster.

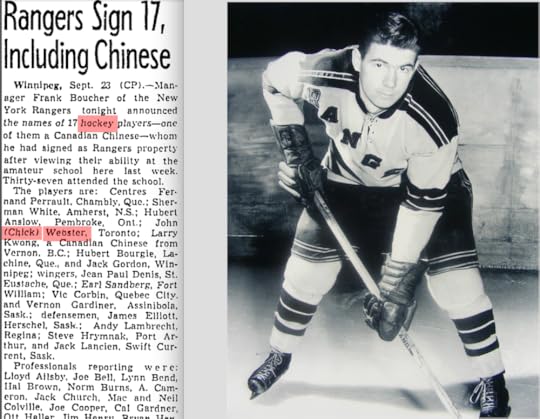

When he got back to Toronto after the end of World War II, Webster was 25 and thought he was too old for a hockey career. His friend Jack Riley (who passed away last summer at the age of 97) convinced him otherwise. After playing briefly with the Uptown Tires team in the Toronto Mercantile League during the early winter of 1945-46, Webster returned to Baltimore to join Jack Riley with the Clippers in the EAHL. His play was impressive enough to attract the attention of the New York Rangers, and he was one of 37 players invited to a Rangers tryout camp in Winnipeg before the next season. On September 23, 1946, Rangers GM Frank Boucher announced that 17 players from the camp had been signed by the club – including Chick Webster.

Webster was assigned to the New York Rovers of the EAHL. “Most of the guys there were just out of juniors, so I think I was a big help to the coach.” But after just a few games, he was promoted to the New Haven Ramblers of the American Hockey League, where he played for nearly three full seasons.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

“I was 30 when the Rangers finally brought me up,” Chick said. “Some guy got hurt.” Actually, it was December of 1949 and he had just recently turned 29. But on January 15, 1950, it was Webster who got hurt. He remembers it as a broken wrist, though other sources say a broken hand. After sitting out a bit, he finished the season in New Haven wearing a leather cast on his arm. His NHL career was over, but he was far from through with hockey.

“The best team I ever played on,” says Webster, “was the Cincinnati Mohawks.” This was in the AHL in 1951-52. “We had Buddy O’Connor and Pat Egan. Emile Francis was our goalie.” He still keeps in touch with Francis, and is occasionally in contact with another Mohawks player who went on to the NHL, Ivan Irwin.

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

shakes hands with a young boy. Film provided by Paul Patskou.

“He seemed to be one of those players who could always be in the play,” says Irwin of his former teammate. “Winning was important to him. It was important to all of us. He was a hustler.”

Webster’s worst experience in hockey came a year later, playing with the Syracuse Warriors in 1952-53. Eddie Shore ran the team. He’d been a huge star in the NHL, but he was a tyrant as a minor league owner and coach. “Shore was a real, real, terrible guy,” Chick says. “If you were sick, or didn’t go on the trips out of town, he’d ask, ‘did you skate?’ I told him I couldn’t get on the ice because the rink was being used. He said, ‘there’s plenty of snow on the ground. You should have gone out on the road and skated.’ Then he fined me.”

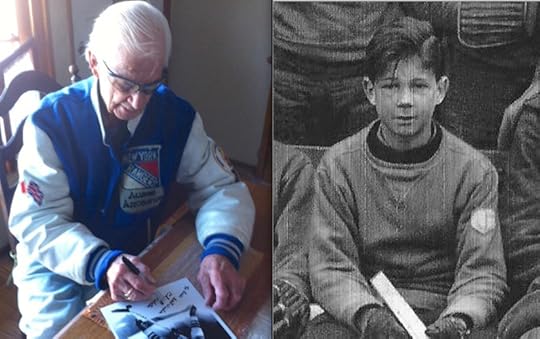

Chick Webster now and then. Signing a photo that has been mailed to me

and the earliest hockey photo of him, Toronto 1934. Courtesy of Rob Webster.

That 1952-53 season would be Webster’s last as a pro, but he continued to play amateur hockey in the Toronto area in Stouffville and Willowdale until the mid 1960s. In 1970, he moved to Mattawa, Ontario, where he played oldtimers hockey well into his 70s. He remains, as his son Rob says, feisty and independent and still living on his own at age 96.

It was a treat to speak with him.

For more on Chick Webster, please see the following stories:

January 3, 2017

Print the Legend…

After my first experience on the internet, I remember thinking, “this is all pretty good, but until I can sit at my desk at home and read through old newspapers, what’s the big deal?”

There once was a time (not all that long ago, really) when the only way you could research old papers was to visit a library and scroll through microfilm. I still do that when I have to, but it probably won’t surprise you to learn that I now spend an awful lot of my time reading old newspapers online.

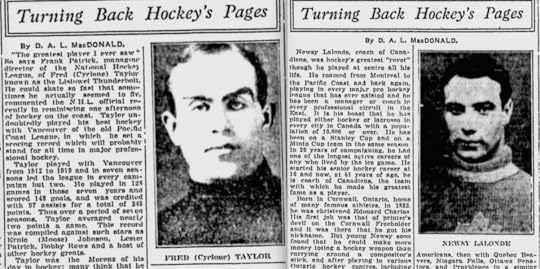

Cyclone’s story appeared in the Montreal Gazette

on January 2, 1934. Newsy’s appeared on February 1, 1934.

While old newspapers can’t answer every question, it seems to me that too many old-time sportswriters didn’t consider any research beyond their own memory to be worth the effort. When we at Dan Diamond & Associates began working on the first edition of Total Hockey in 1997, it was amazing to me to see how often the statistics (mainly compiled from old newspapers on microfilm by Ernie Fitzsimmons) didn’t match up to the stories that had always been told.

I don’t know why this particular bit has stuck in my mind for nearly 20 years, but it has. Written accounts for legendary Montreal Canadiens goaltender Bill Durnan had always said something along the lines of, “he first came to prominence with the Sudbury juniors in the OHA finals of 1934…” Yet the stats now showed that Durnan had actually played in Sudbury the year before. (The text in the Durnan bio was corrected in the second edition of Total Hockey.)

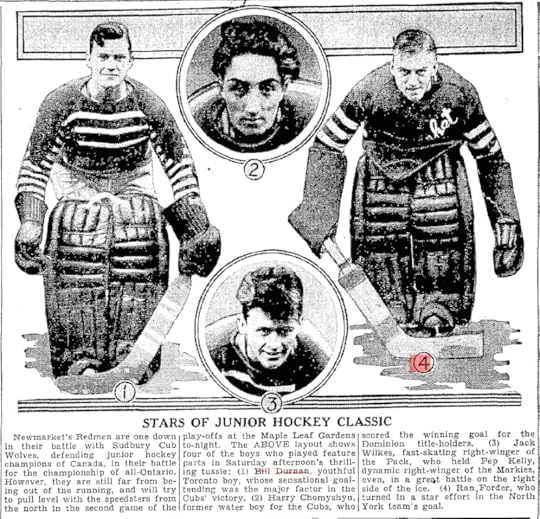

Today, with a few clicks and some clever search terms, there’s Durnan (apparently already wearing his ambidextrous gloves!) tending goal for Sudbury against Newmarket during the Ontario junior finals of 1933.

Bill Durnan and company appeared in the Toronto Star on March 20, 1933.

In the great scheme of things, does it really matter where and when some old hockey player played? Well, think of it this way. What if we were still this sloppy about political history, or military history … or current sports reporting? That’s why there are plenty of us out there trying to get these old facts right.

There’s a line in a classic movie. (Actually, John Ford used it in two of his classic westerns; email me or comment if you know which two!) It goes, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” For a long time, that was all anyone bothered to do. But that shouldn’t be good enough anymore!

To the best of my knowledge, the first big effort to really tell the stories of old-time hockey began 83 years ago yesterday, on January 2, 1934, when D.A.L. MacDonald printed the first of his series, Turning Back Hockey’s Pages, in the Montreal Gazette. On Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays (occasionally on other days of the week too) during the 1933-34 and 1934-35 seasons, a total of 84 articles appeared. Most were on old-time hockey stars, some were about early teams, and at least one was about the Hod Stuart Memorial Game (which I’ve mentioned in these pages before). The stories cover players from the 1880s through the 1920s. Many of them are still big names in hockey history; others are long-forgotten.

I haven’t yet read them all, but, generally speaking, the stories are fantastic. MacDonald had clearly gone through years of back issues of the Gazette, and yet even his sincere effort to do more than just print the legends is filled with all sorts of little errors. Wrong dates, wrong team names. That sort of thing. In the feature on Cyclone Taylor, for instance, it mentions him playing with “Portland Lakes” when the team was actually Portage Lakes. Not the worst of errors, admittedly, but an error nonetheless. And there are lots of others like them.

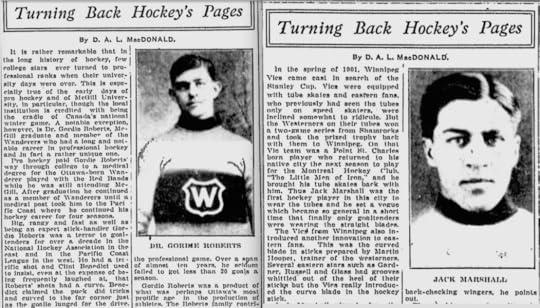

Gordie Roberts was featured on January 25, 1934; Jack Marshall on February 13.

Of the pieces I’ve read, the only one where it appears that MacDonald actually had input from the player being featured is the story on February 13, 1934, about future Hall of Famer Jack Marshall. His career at the game’s highest level had stretched from 1898 to 1917, and his take on the then current game rings familiar today.

“They talk about the dearth of goals nowadays,” says Marshall. “No wonder. Look at the goaltenders padded up like stuff pigeons. Do you know why goaltenders first wore pads? It was for personal protection. And do you think a ten-inch pad on either leg is absolutely necessary for protection?”

“That,” writes MacDonald, “is his answer to what is the matter with present day hockey.”

Jack Marshall lived until 1965. Long enough to see Bobby Hull and his slap shot; Jacques Plante and his mask. I wonder if he ever changed his mind? Then again, just the other day at the Centennial Classic, when he was named one of the 100 greatest players of all time, Hall of Fame goalie Glenn Hall said: “Today’s goalkeepers are great, and you get some skinny little fella and he’s got on pants that are 10 times too large.”

But as I’ve pointed out here before, the question of how much protection for goalies is too much is one that people have been asking for a very long time!

December 21, 2016

Top Toronto Rookies…

The Toronto Maple Leafs have certainly been a much more entertaining team to watch this season. Still, with two games to go before a four-day break over Christmas, they currently sit in last place in the Atlantic Division – although only six points out of third place, which would net them a playoff spot.

While it wouldn’t be impossible, I don’t believe they’ll make the playoffs this year. Even so, with rookies Auston Matthews and Mitch Marner, plus William Nylander and several others, Leafs fans seem satisfied that the plan in place of building patiently through the NHL Draft is already showing positive results.

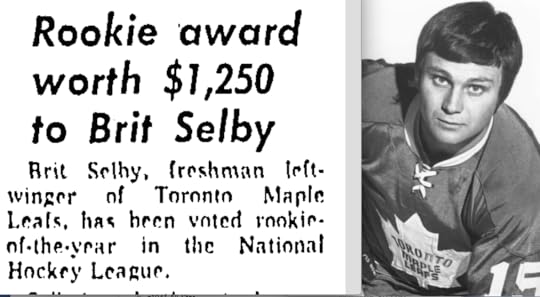

Brit Selby was the last Maple Leaf to be named rookie of the year back in 1965-66.

With Matthews turning 19 just a month before the start of the season, and Marner not turning 20 until May, these two may well be the most promising pair of teenagers to join the team together since 19-year-old Charlie Conacher and 18-year-old Busher Jackson way back in 1929-30. Matthews is on pace to break the Maple Leafs rookie record of 34 goals, set by Wendel Clark as a 19-year-old (and #1 overall draft pick, like Matthews this year) back in 1985-86. Yet like Wendel, who finished second in Calder Trophy voting behind Gary Suter that season, Matthews is certainly no shoo-in as the NHL’s rookie of the year. Patrick Laine is currently outscoring him in Winnipeg, and rookie defenseman Zach Werenski has been impressive as well for the surprising Columbus Blue Jackets.

There was not yet a Calder Trophy for rookie of the year when Charlie Conacher and Busher Jackson broke into the NHL. Conacher led all NHL newcomers with 20 goals in just 38 games played that season. That may have won for him, if there’d been a reward, but the best newcomer during that season was probably Detroit’s future Hall of Famer Ebbie Goodfellow. He played the full 44-game schedule and had 17 goals and 17 assists to top all rookies with 34 points.

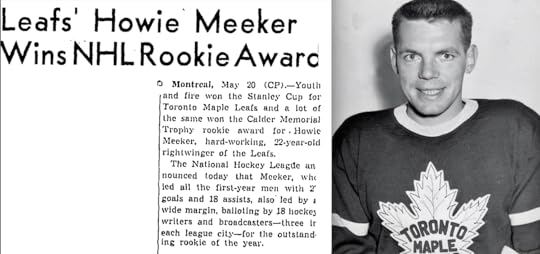

Howie Meeker was top rookie in 1946-47, but didn’t get all that he should have for it.

Though it’s not talked about nearly as much (for obvious reasons!), Toronto’s Calder Trophy drought is even longer than its Stanley Cup drought. This season marks 50 years since Toronto’s last championship in 1967, but 51 years since Brit Selby was named rookie of the year in 1965-66.

Selby had just 14 goals and 13 assists in 61 games as a Leafs rookie in 1965-66, but comfortably outpointed Bert Marshall and Gilles Marotte (98-90-68) in Calder Trophy voting that year. Clearly, though, the best rookie in the long run from that season would turn out to be goalie Bernie Parent, who finished fourth in the voting with 69 points.

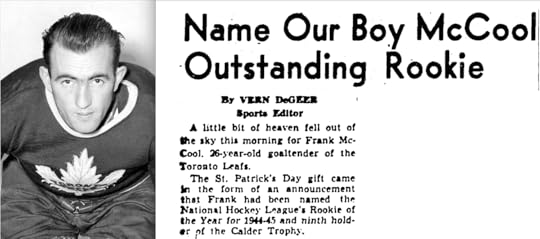

Frank McCool was a wartime replacement who battled debilitating ulcers.

After helping Toronto win the Stanley Cup as a rookie in 1944-45,

he was out of hockey by the end of 1945-46.

Selby, and Kent Douglas, who won the Calder for Toronto in 1963, hardly went on to superstars careers – although Dave Keon, who won it in 1961, certainly did. All in all, through the years, most of the NHL’s rookies of the year have gone on to be fine players. Many have gone on to Hall of Fame careers. But there are some quirks. Frank Mahovlich beat out Bobby Hull for the Calder in 1958, and though both went on to stellar careers, it’s hard to argue that Hull wasn’t the better player in the long run. Back in 1946-47 (when the Leafs underwent a similar youth movement to what we’re seeing this year,) Howie Meeker was clearly the NHL’s best rookie and was deservedly rewarded with the Calder Trophy – as he should have been. Yet who could disagree that a kid in Detroit by the name of Gordie Howe went on to become the better player!

According to Meeker, who tells the story in his own book, Golly Gee, It’s Me and told it to author Greg Oliver for his book, Written in Blue and White, Leafs owner Conn Smythe had promised him a $1,000 bonus if he won a league trophy in his rookie season. Oliver points out that there is no such clause in the contract, but Meeker tells him that “[Smythe] told me verbally twice, and we shook hands on the deal.”

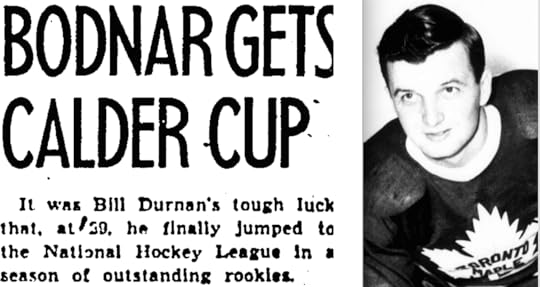

Gus Bodnar’s goal 15 seconds into his first game on October 30, 1943, is still an

NHL record for the fastest goal by a player in his NHL debut. He had a

career high 22 goals and 40 assists as a rookie, but was still a surprise winner

of the Calder Trophy over Montreal goalie Bill Durnan.

When he won the Calder Trophy, the Globe and Mail noted: “Meeker also collected a $1,000 bonus, given by the NHL for the first time this year. The bonus will be matched by another $1,000 from Maple Leaf Gardens.” So, clearly, more than just Meeker and Smythe were aware of the promise, and yet Meeker never got his money. As he told Oliver: “When the time came around, [Smythe’s] excuse was ‘You got $1,000, but it was from the NHL.’” Meeker wasn’t happy! “I was pissed off for a long time,” he told Oliver.

At the time, Meeker was the fourth Toronto Maple Leafs player to win the Calder Trophy in five seasons, following up on three straight wins by Gaye Stewart (1943), Gus Bodnar (1944) and Frank McCool (1945).

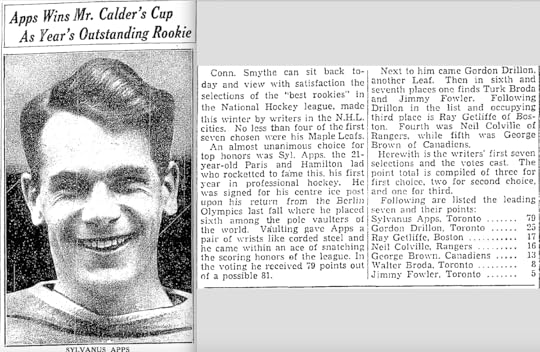

Syl Apps was recently named #2 all-time among the Leafs’ top 100 players,

behind 1961 Calder Trophy winner Dave Keon.

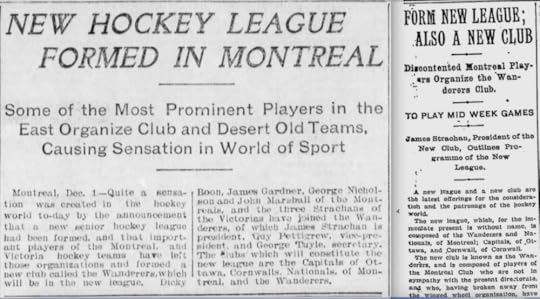

Still the strongest season in history for Leafs freshmen was likely 1936-37. This was the first year in which NHL president Frank Calder provided a trophy for the league’s best rookie and Toronto players finished 1-2 in the voting. Syl Apps, having finished just one point back of Sweeney Schriner for the NHL scoring title, won the Calder Trophy. Gordie Drillon (who would win the scoring title the following year – the last Leaf ever to do so!) finished second. And if you don’t recognize the name of that guy who finished sixth in the Calder voting that year, it might be because you know him better as Turk Broda.

December 14, 2016

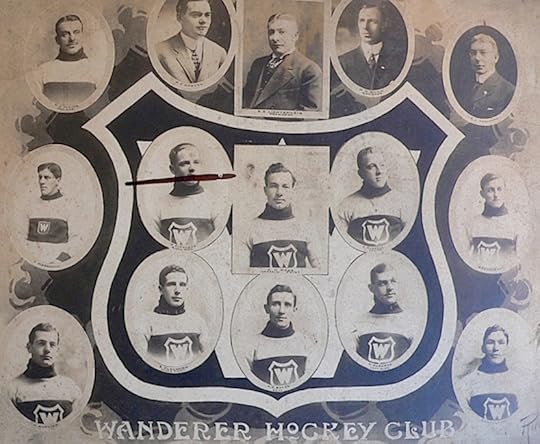

The Montreal Wanderers

This past weekend, various “this day in history” sources noted that December 10, 1924, marked the first “All-Montreal” game in NHL history. The Montreal Canadiens defeated the NHL’s new Montreal expansion team (who, as I mentioned two weeks ago, had no nickname at this point) 5-0 that day at the Mount Royal Arena. But, as my Society for International Hockey Research colleagues Todd Denault and Lloyd Davis noted on Facebook, this was actually the second “All-Montreal” game in NHL history. The first came on December 22, 1917.

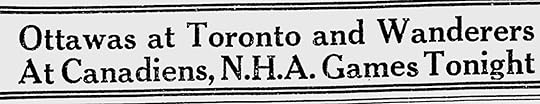

Banner atop the sports page in The Toronto World, December 22, 1917.

On that date 99 years ago, on just the second night of action in NHL history, the Canadiens crushed the Montreal Wanderers 11-2. The Canadiens featured six future Hall of Famers in their nine-man lineup that night: Georges Vezina, Joe Hall, Joe Malone, Newsy Lalonde, Didier Pitre and Jack Laviolette. The Wanderers had two, both playing in their final season: Art Ross and Harry Hyland.

Accounts from the Montreal Gazette and the Toronto World, December 24, 1917.

Like its two star players, the Wanderers team was nearing the end of its time too. Art Ross (who was both player and manager) and owner Sam Lichtenhein had not been quiet about the fact that their team was undermanned heading into the inaugural NHL season. After winning just one of their first four games, the Wanderers were only too happy to bow out after fire destroyed the Montreal Arena on January 2, 1918.

Fiery times were nothing new to this franchise, which was born of trouble and died of trouble. They were often in the centre of any hockey storm.

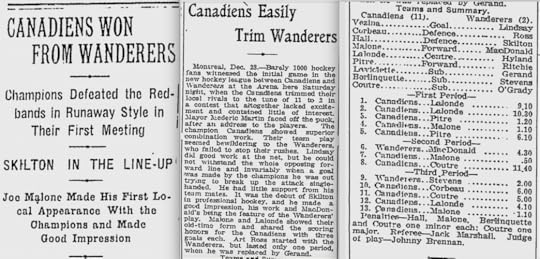

The Wanderers were officially formed on December 1, 1903, when several key players from the Montreal Hockey Club broke ranks with the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association over the running of the team. These players enticed a few members of the Montreal Victorias to join them, and not only set up their own new team, but also formed a rival league to play in, breaking away from the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (the NHL of its day) to establish the Federal Amateur Hockey League.

Accounts of the formation of the FAHL and the Wanderers in the

Winnipeg Tribune

on December 1, 1903 and the Montreal Gazette on December 2.

In reading about the early history of the Wanderers, you’re likely to come across stories about how they chose their name because they intended to wanderer across Canada, playing challenges for the Stanley Cup. I have my doubts about that!

For one thing – and all their players would have known this! – once the Wanderers became Stanley Cup champions (which they soon would), they would be entitled to host those challenges at home. For another, there was plenty of newspaper coverage of their story all across the country and none of the players were even willing to discuss what had led to their break with the Montreal AAA. Even if they felt their new team was championship material, they don’t seem like the types to have bragged about it so openly. Also, “Wanderers” was already a popular team name in English soccer. It’s thought to have started with teams that had no clear home base and played mainly as travelling clubs. The hockey Wanderers always intended to call Montreal home, but perhaps the name appealed to the players for the somewhat renegade status it would give to their breakaway club.

It certainly seems that no matter who owned the Wanderers, or who played for them, the team was always a maverick. In their not quite 15 seasons of existence, the Wanderers were involved in the formation of at least four new hockey leagues, and as many as six depending on how you choose to count a couple of name changes. After winning the Stanley Cup in 1905-06, they became the first team in Canada to openly pay for players in a sport that was supposed to be strictly amateur. Their part in the formation of the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) is explained in great detail in my biography Art Ross: The Hockey Legend who Built the Bruins and in my novel Hockey Night in the Dominion of Canada so I won’t go into it here. (If you haven’t read them, why not?!?)

The Montreal Wanderers of 1911-12 from Art Ross: The Hockey Legend

Who Built the Bruin (photograph courtesy of the Ross family.)

After Stanley Cup championships in 1906, 1907, 1908 and 1910, the Wanderers began to fall on hard times during World War I, as did several other professional hockey teams. The team was losing money, and clearly, re-forming the NHA as the NHL was not going to help the Wanderers any. The fire that destroyed the Montreal Arena came at a pretty convenient time for them.

Was it too convenient?

In Volume One of The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Charles Coleman notes: “The fire started from an unknown source in the Wanderer dressing room.” Coleman’s book is compiled mainly from items he found in newspapers, so I have to think someone in Montreal wrote that at the time.

I honestly can’t recall whether or not Coleman’s book is the first place I read that about the fire, but it always sounded suspicious to me. Was it some sort of anti-Semitic shot at Sam Lichtenhein hinting that he’d had the Arena burned down on purpose? A twist on the racist phrase “Jewish Lightning,” in which arson is committed to collect the insurance money?

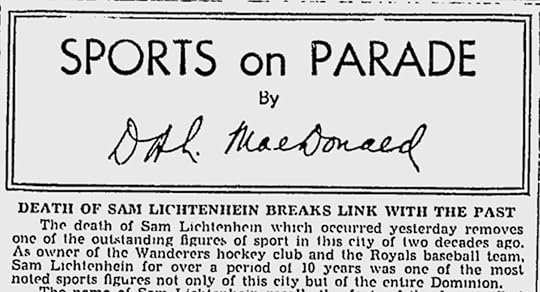

From the Montreal Gazette, June 22, 1936

The truth is, fires destroyed an awful lot of sports venues back in the day, and Lichtenhein had carried on with the Montreal Royals baseball team despite fires burning down the grandstand in ballparks they played at in 1914 and 1916. Fires, it seems, followed Lichtenhein around. According to an obituary by D.A.L MacDonald in the sports section of the Montreal Gazette shown above, Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871 had destroyed his father’s business and was the reason the family had moved to Montreal in the first place. And yet something about that sentence still bothers me…

December 6, 2016

The NHL’s First Game?

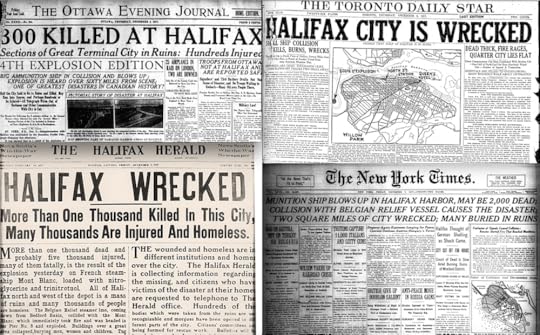

Ninety-nine years ago today, on December 6, 1917, at 9:04 Atlantic Time (just about the time I’ve set this story to be published), the French ship Mont-Blanc, with a cargo of military explosives intended for the First World War, blew up in the harbour at Halifax shortly after colliding with the Norwegian vessel Imo. The explosion – often said to be the largest man-made blast until the Atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima – destroyed the community of Richmond in the north end of Halifx, leveling buildings, snapping trees, bending iron rails and shattering windows throughout the entire city of 50,000. In fact, the blast shattered windows 100 kilometers away in Truro, Nova Scotia, and could be heard in Prince Edward Island.

Close to 2,000 people were killed and another 9,000 injured. Some 25,000 people were left without adequate shelter. The Halifax Explosion resulted in $35 million in damages, which would be close to $600 million today. Rescue efforts began almost immediately – although they would be hampered by a blizzard that struck the next day. Supplies and money soon arrived from across Canada and the northeastern United States.

Newspaper accounts of the Halifax Explosion, December 6 & 7, 1917.

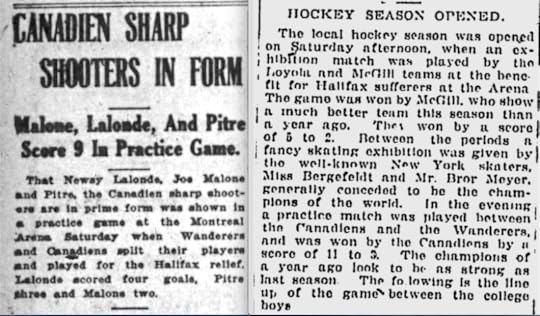

The hockey community did its part too. In Montreal the new season opened on Saturday, December 15, 1917, with a pair of fundraising games for the Halifax relief effort. The second of those games was little more than a glorified scrimmage, but was, in fact, the first game played in the history of the NHL – or, at least, the first game contested by players belonging to NHL teams.

I’m not the first to write about this – although I only know of two other sources. (One is the excellent 2002 book Deceptions and Doublecross by Morey Holzman and Joseph Nieforth about the formation of the NHL and the other is the web site Third String Goalie.) Neither says much about the game … but that’s likely because there was so little written about it at the time, and what there was is rather conflicting.

The NHL had been formed from the ashes of the recently defunct National Hockey Association in late November of 1917 and would officially open its schedule on December 19. This exhibition game on December 15 – despite what the Montreal Gazette says in the clip below – was played by mixed teams made up of players from the Montreal Wanderers and the Montreal Canadiens. The lineups in both the Gazette and the Montreal Star show the teams as follows:

Team 1 Team 2

Bert Lindsay (W) G Georges Vezina (C)

Jack Laviolette (C) D Joe Hall (C)

Dave Ritchie (W) D Bert Corbeau (C)

Joe Malone (C) F Harry Hyland (W)

Newsy Lalonde (C) F Jack McDonald (W)

Didier Pitre (C) F Billy Bell (W)

Louis Berlinguette (C) Sub Billy Coutu (C)

Phil Stephens (W) Sub George O’Grady (W)

Brief coverage of the game in the Ottawa Journal

(December 18) and Montreal Gazette (December 17).

Team 1 was the winner, but different sources list the score as 11-3, 10-3, and 10-2. The Montreal Star has it as 10-3 and reports the scorers as Lalonde (4), Pitre (3), Malone (2) and Berlinguette for the winners with Hyland scoring all three for the losers.

One night before the games in Montreal, the senior amateur season of the Ontario Hockey Association kicked off in Toronto on Friday, December 14 with its own exhibition for the Halifax Relief Fund. The defending Allan Cup champion Dentals Hockey Club of Toronto (and, yes, they were all either dental students or recent graduates of the dental program affiliated with the University of Toronto) defeated the Hamilton Tigers 5-4.

Toronto’s Globe newspaper ran an ad for the local benefit game on December 14

and had a brief summary of the game in Montreal on December 17.

Though it was advertised as a fundraiser (and said afterwards to have been a very entertaining game), only 1,200 fans showed up. No account seems to give the attendance for the games in Montreal, and nothing I’ve come across indicates how much money was actually raised in either city for the victims in Halifax.

November 29, 2016

Expansion Now and Then

The NHL’s newest team officially got a name last week when it was announced that the expansion franchise in Las Vegas for 2017-18 will be known as the Vegas Golden Knights. The official colours will be steel grey (for strength and durability), gold (because Nevada is the largest producer of gold in the USA), red (for the Vegas skyline and the Red Rock canyons of the nearby desert), and black (for power and intensity.) Grey, Black and Gold are also the colours of the United States Military Academy at West Point, whose sports teams are known as the Black Knights, and where the new hockey team’s majority owner Bill Foley graduated in 1967.

There have actually been professional hockey teams in Las Vegas since 1970, and serious interest in an NHL team since 2007. The current ownership group has been involved in the discussion since the spring of 2014. The NHL authorized a formal expansion process on June 24, 2015 and made applications available to interested parties that July. It was then announced on July 21, 2015, that Las Vegas and Quebec City had applied. Nearly a year later, on June 22, 2016, it was announced that Las Vegas would become the NHL’s 31st team. Five months later, the team got its name. In about 11 more months, they’ll play their first game.

Things moved a lot faster when the NHL first expanded back in 1924! Yes, teams had been added – and subtracted and relocated – prior to this, but the admission of a second Montreal team and the first U.S. club for the 1924-25 season (which saw the league grow to six teams – although not the so-called “Original Six”) was the first true expansion.

There had been internal talks for a few years already, but the first public indication that the NHL was considering the addition of American teams came in March of 1924 when Colonel John Hammond, representing Madison Square Garden of New York, and Charles Adams of Boston were invited to Montreal during the Stanley Cup playoffs. Reports on March 20, 1924, had Adams confirming that he’d purchased an option on a franchise for Boston. Little more is heard again until September 26, but by September 30, the Boston Arena had agreed to give ice to Adams for his new team, and Art Ross had agreed to serve as the coach, manager and vice president.

The NHL wouldn’t actually confirm the new entries in Boston and Montreal until October 12, 1924; the Boston Professional Hockey Association, Inc. wasn’t officially formed until October 23; and formal approval of the franchises didn’t actually come until the NHL’s annual meeting in Montreal, on November 1, 1924. Even so, the two teams would play their first games against each other in Boston just one month later– meaning there was no time to waste!

On September 30, 1924, it had been reported that Boston would take over the now-defunct Seattle franchise of the rival Pacific Coast Hockey Association, but that story quickly proved false. Ross would sign a few over-the-hill PCHA veterans for the new Boston team, but mainly he was on the road for the next few weeks trying to recruit promising amateurs. Most of the players he assembled met up in Ross’s hometown of Montreal on November 14, 1924, and proceeded to Boston together by train. The team also got its name that day, and its colours too. Brown and yellow, same as Adams’ chain of grocery stores. (Black would replace the brown in the Bruins uniform in 1934–35.)

“An interesting item is connected with Pres. Adams’ partiality towards brown as the team color,” noted that day’s Boston Globe. “The pro magnate’s four thoroughbred [horses] are brown … his Guernsey cows are of the same color; brown is the predominating color among his Durco pigs on his Framingham estate, and the Rhode Island hens are brown, although Pres. Adams wouldn’t say whether or not the eggs they lay are of a brown color.” Browns was even considered as the team nickname, but Adams was concerned that people would call them the Brownies, which struck him as childish. The team name, of course, would be the Bruins.

The stories surrounding the Bruins name are all pretty much the same. Charles Adams held a contest, but had very definite ideas about what kind of name he wanted. He wanted the name to relate to “an untamed animal.” He wanted the animal to be big, strong, ferocious and smart. (Of course, it wouldn’t hurt if that animal happened to be brown!) A secretary in the team office is usually given credit for coming up with Bruins – which comes from an old English term for a Brown bear first used in a medieval children’s fable. In his book “The Bruins” famed hockey writer Brian McFarlane specifically names Bessie Moss, whom he says was a transplanted Canadian working for Art Ross in Boston. When I was working on my Art Ross biography, I asked McFarlane about the story – which had proven impossible for me to confirm. He was pretty sure he’d come across it in either an old book or newspaper story some time during his hockey travels in the 1970s, but no longer had the source among his collection.

Whoever and however they got the name, the Bruins hit the ice for their first practice on November 15, 1924, and played their first game on Thanksgiving night, Thursday, November 27. It was an exhibition game against the Sasktoon Sheiks of the Western Canada Hockey League. Boston lost 2-1. They would beat their expansion cousins from Montreal (who were not officially named the Maroons until the following season) by the same 2-1 score in their first NHL game on December 1, 1924. Still, it would be a long, trying, season for the Bruins, who finished that first year with a record of 6-24-0. Montreal was only slightly better at 9-19-2.

The NHL will be counting on a better showing by Vegas – but they’ll be hard pressed to match the Maroons, who improved so quickly they won the Stanley Cup in their second season, or the Bruins, who were champions by year five.

November 22, 2016

Pyle and the St. Pats

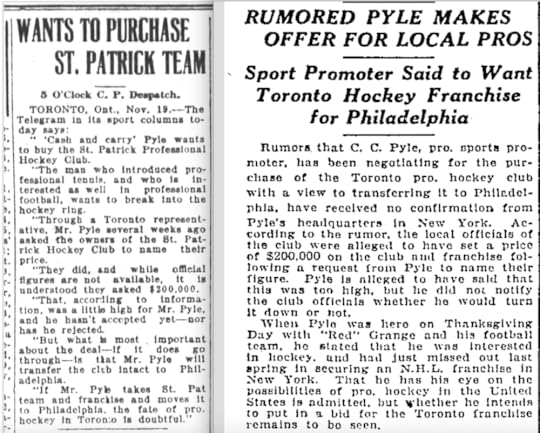

In my story last week, I made a brief mention of C.C. Pyle as the agent for both Red Grange and Suzanne Lenglen. Charles C. Pyle (sometimes referred to as “Cold Cash” Pyle, and more often as “Cash and Carry” Pyle) was responsible for bringing both stars to Toronto in the fall of 1926 … but he was looking to take something away with him too: the city’s professional hockey team – The Toronto St. Pats.

Suzanne Lenglen and her agent, C.C. Pyle.

Writing in the Toronto Daily Star on October 8, 1926 (a few days before Lenglen’s appearance in the city), W.A. Hewitt noted: “Cash-and-Carry Pyle, who has Red Grange and Suzanne Lenglen under his wing, is trying desperately to break into professional hockey…” Hewitt wrote that Pyle had recently raised his original offer of $200,000 to $400,000 in an effort to buy the New York Americans, the NHL’s first franchise in The Big Apple.

By the middle of November, shortly after Grange’s visit to Toronto, came stories that Pyle had now set his sights on breaking into the NHL through Toronto. He had asked the owners of the St. Patricks what it would take to buy their team and was reportedly told $200,000. Though he’d offered double that for the Americans, Pyle was said to consider this price too high for the Toronto team. (Conn Smythe – who would soon put together a syndicate to buy the St. Pats for $160,000 – told the Star in 1977 that the team “might have been worth $15,000.”)

The Toronto Telegram had the story of Pyle’s interest in the St. Pats first on November 19.

Other local papers, such as the Globe, shown here, didn’t have it until the next day.

While it appears there would be more serious offers from Montreal investors (who likely would have left he team in Toronto) in the coming weeks, it was widely reported that if Pyle bought the St. Pats, he would move them to Philadelphia. Smythe used this threat of losing the city’s NHL team to an American city to rally his own group of investors and save the team in Toronto. He closed his deal on February 14, 1927, and renamed the team the Maple Leafs.

How close did Toronto really come to losing its team in 1926? It’s hard to know for sure. But C.C. Pyle’s interest in hockey seems to have been genuine. In the spring of 1927, he and Red Grange bought a large rink in Los Angeles, made plans to build another in San Francisco, and announced their intention to establish a four-team California Professional Hockey League. The league would run until 1933, though Pyle and Grange sold their interests in it around 1929.

November 16, 2016

Three Stars in Three Months

Over a three-month period 90 years ago, during the fall of 1926, three of the greatest sports stars of the Roaring Twenties made appearances in Toronto. A time-machine type of moment for someone like me, and yet – given the historical significance of these performers – they don’t appear to have attracted the size of crowds they should have.

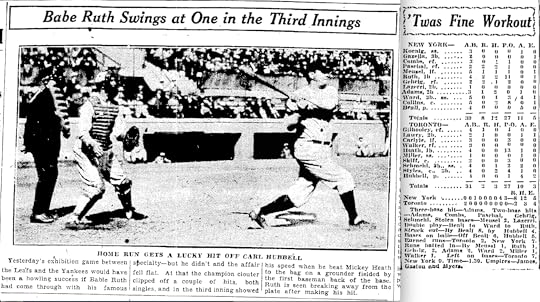

First up was Babe Ruth, who appeared on a Friday afternoon, September 10, 1926, for an exhibition game between the New York Yankees and the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team. The Yankees featured most of their star players, including Tony Lazzeri, Mark Koening and Bob Meusel, although Ruth played first base in this game and when Lou Gehrig came in late it was as the right fielder.

Photograph from the Toronto Star, box score from the Globe, September 11, 1926.

The Leafs, behind soon-to-be New York Giants star Carl Hubbell, led 2-1 for most of the game before the Yankees scored four in the eighth and three in the ninth for an 8-2 victory. The whole game was played in just an hour-and-a-half! Only about 6,000 fans showed up at Maple Leaf Stadium, and by most accounts, it wasn’t much of a game. The crowd had come to see Ruth hit home runs, but he managed only two singles. Still, he was swarmed on the field by about 100 young boys the moment the game ended.

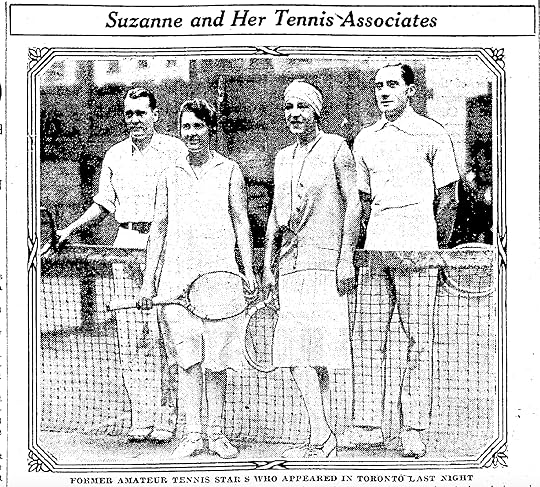

A month later, on October 12, 1926, tennis star Suzanne Lenglen of France was in Toronto. Lenglen was the Serena Williams of her day. Not only was she the world’s most dominant female tennis player, she helped to change tennis fashions and was a hard-nosed businesswoman. In an era when tennis was strictly amateur, she was the first to become a professional. In fact, that’s what brought her to Toronto. It was her second stop on a pro exhibition tour across North America that had begun at Madison Square Garden in New York two nights before.

Lenglen’s star power had made tennis a popular spectator sport, and while I couldn’t find a specific attendance figure for her exhibition at Toronto’s Arena Gardens, stories note it was a large and particularly well-dressed crowd. Lenglen defeated American Mary Browne 6-0, 6-2 in a singles match, but she and her French partner Paul Feret were defeated by Browne and fellow Californian Harvey Snodgrass in mixed doubles.

Photo from the Toronto Star, October 13, 1926. Lenglen is wearing the head scarf.

Of particular note throughout her tour was the question of why Lenglen had turned pro – a widely criticized decision that saw the All-England Club at Wimbeldon (where she had won six championships in a seven-year span) revoke her honorary membership. Lenglen was up front about it, saying she did it for the money. She estimated that she’d made millions of francs for others while spending thousands of her own on entrance fees.

“I have worked as hard at my career as any man or woman has worked at any career. And in my whole lifetime I have not earned $5,000 – not one cent of that by my specialty, my life study – tennis…. I am twenty-seven and not wealthy – should I embark on any other career and leave the one for which I have what people call genius? Or should I smile at the prospect of actual poverty and continue to earn a fortune – for whom?

“Under these absurd and antiquated amateur rulings, only a wealthy person can compete, and the fact of the matter is that only wealthy people do compete. Is that fair? Does it advance the sport? Does it make tennis more popular – or does it tend to suppress and hinder an enormous amount of tennis talent lying dormant in the bodies of young men and women whose names are not in the social register?”

Another professional pioneer was in Toronto the next month, on November 8, 1926, when Red Grange was in town to play football. Grange had been a star at the University of Illinois at a time when college football ruled the sport and the fledgling National Football League was barely an afterthought. Grange – known as “The Galloping Ghost” – changed all that with his decision to sign with the Chicago Bears in 1925. He drew huge crowds to NFL games that season, and as a barnstormer afterward, but when he got into a dispute with Bears owner George Halas, Grange and his agent C.C. Pyle (who also represented Suzanne Lenglen!) formed their own team and their own league the following year.

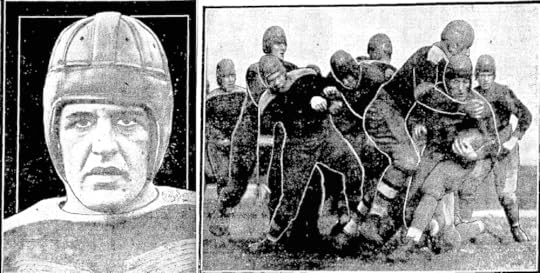

Red Grange on the left, an action shot of the game on the right.

From the Toronto Star, November 9, 1926.

Grange was playing with the New York Yankees of the American Football League when he came to Toronto for a league game against the Los Angeles Wildcats at Maple Leaf Stadium. Unlike the huge crowds he attracted in the United States, there were only about 10,000 to 12,000 fans at this game. After a scoreless first half, Grange scored on a 70-yard touchdown run and the Yankees went on to a 28-0 victory.

Legendary Toronto sportswriters W.A. Hewitt (father of Foster), Lou Marsh and Mike Rodden all covered the game. Given today’s NFL-envy among so many Toronto football fans, it’s interesting to note that these writers believed the Toronto crowd was unimpressed with the American rules. Too much passing; not enough running; and not enough kicking. (The game was called football, after all!) And where were the single points? Why didn’t the American players have to run back punts? Why wasn’t the ball turned over when the punting team downed it? Forward passing was not yet allowed in Canadian football, and the fans also wondered why it wasn’t a fumble when an incomplete pass hit the ground.

All in all, the Canadian fans (or, at least, the sportswriters) felt there were just too many rules in American football. And for his part, Grange – who attended a game between Balmy Beach and the Hamilton Tigers at Varsity Stadium earlier in the day – liked all the punting and the running … but he thought the Canadian game was too rough!

November 8, 2016

I Love A Parade

Well, after 108 years of waiting, Cubs fans couldn’t have asked for a much nicer day for a parade last Friday. They say there was a total of 5 million people who lined the streets or were on hand for the “Cub-stock” rally at Grant Park.

According to Major League Baseball’s web site, it was the seventh-largest gathering of human beings in world history… and the largest ever in the Western Hemisphere.

Kumbh Mela pilgrimage, India, 2013 (30 million)

Arba’een festival, Iraq, 2014 (17 million)

Funeral of C.N. Annadurai, India, 1969 (15 million)

Funeral of Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran, 1989 (10 million)

Pope Francis in the Philippines, 2015 (6 million)

World Youth Day, 1995 (5 million)

Cubs World Series parade (5 million)

Funeral of Gamal Abdel Nasser, 1970 (5 million)

Rod Stewart concert, Brazil, 1994 (3.5 million)

Hajj pilgrimage, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 2012 (3 million)

Since the parade, Cubs players have been to Disney World, appeared on Saturday Night Live, and taken the World Series Trophy to a Blackhawks game. None of them, however, have attempted to duplicate the old Blackhawks’ celebratory feat of rolling a star player through the downtown business area in a wheelbarrow.

Not only did Roger Jenkins do this with goalie Chuck Gardiner in 1934,

He did it again with Mike Karakas in 1938.

But it seems that this odd wheelbarrow tradition dates back nearly as far as the Cubs’ last World Series win in 1908, as it may well have begun with hockey’s Quebec Bulldogs in 1912 – a story that appears in a couple of my children’s books and which I often tell when I’m visiting classrooms.