Eric Zweig's Blog, page 26

May 20, 2015

Kitty Bars the Door Again 100 Years Later

You don’t hear the terms Neutral Zone Trap or Left Wing Lock much these days, but the NHL is once again in a scoring slump. There’ve been exciting games in the current playoffs, and a few 6-2 scores, but basically, postseason play has resembled the low-scoring pre-lockout days of the late 1990s and early 2000s, complete with plenty of clutching and grabbing.

“When I came into the league,” said Sidney Crosby shortly after his Pittsburgh Penguins were eliminated in round one by the New York Rangers, “you knew [penalties] were going to be called because the league was promoting a certain style of play. Now I don’t know… Cleary the standards have changed.”

During the regular season, Jamie Benn of the Dallas Stars won the Art Ross Trophy with just 87 points in 82 games. It’s the lowest total in a non-lockout season since Stan Mikita scored 87 in 72 games in 1968–69, and the lowest points-per-game total since Elmer Lach led the NHL with 61 points in 60 games in 1947–48. That was the year that Art Ross and sons donated their trophy to the NHL to reward the league’s leading scorer.

The Art Ross Trophy is what Art Ross is best known for today. To many fans, it’s all he’s known for – although students of NHL history know he spent 30 years running the Boston Bruins from their inception in 1924 through 1954. Before that, during the pre-NHL years from 1905 to 1917, Ross was one of the best defensemen in hockey. His was a high-scoring era, and Ross was a star at both ends of the ice. He wasn’t Bobby Orr on offense. Probably closer to Raymond Bourque, only rougher. (It was once said of Ross that he never started a fight, but never came out second best in one either!) His stamina would make Chicago’s Duncan Keith look like a shirker – although Ross was one of the first to speak out in favor of more frequent substitutions in an era of 60-minute men.

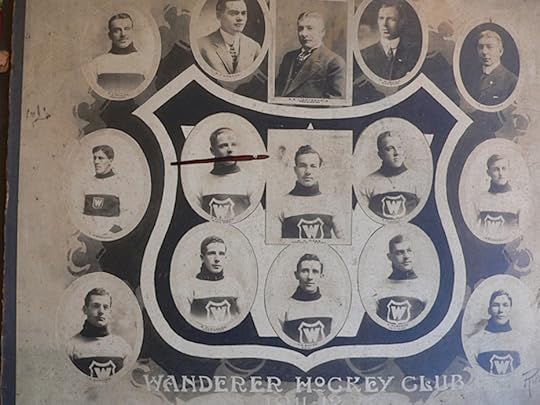

Captain Art Ross of the 1911-12 Montreal Wanderers is pictured in the center square.

Today, his name is synonymous with offense, but Art Ross is credited for coming up with hockey’s original defensive-trap system 100 years ago this spring … although Ross’s role in devising it may be less fact and more fiction.

Ross was playing with the Ottawa Senators in 1914–15 and was going up against his longtime former team, the Montreal Wanderers, in a tie-breaking playoff to decide the championship of the National Hockey Association, forerunner of the NHL. The Wanderers of Sprague and Odie Cleghorn, Gord Roberts, and Harry Hyland (largely forgotten now, but big names in their era) were hockey’s best offensive team. They scored 127 goals during the 20-game schedule of 1914–15 for an average of 6.35 goals-per-game! Ottawa scored just seventy-four times, but the Senators’ sixty-five goals against were by far the fewest in NHA.

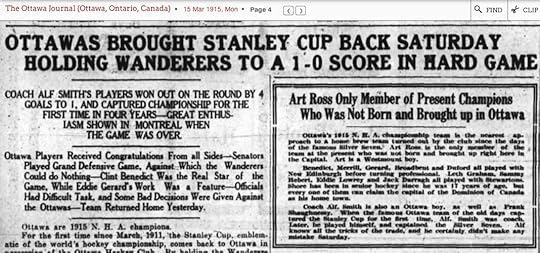

But this was a time when scorers ruled the ice, so the Wanderers were favoured over the Senators when their two-game, total-goals playoff opened on March 10, 1915. Even after Ottawa won the opener 4–0 at home (future Hall of Famer Clint Benedict’s shutout that night was the first in the NHA all season!) the Wanderers were expected to rally at home. After all, they’d beaten the Senators 15–6 and 8–1 in their two regular-season meetings in Montreal.

Newspapers speculated that Ottawa would come out hard in game two on Saturday night, March 13, looking for a few more goals to put the series away. But right from the opening face-off the Senators’ true intentions were clear. Ottawa employed only a center plus one winger on the forward line and spread out three defensemen across the ice.

“I was the only man to move,” Ross recalled around 1949. “I played right defense and if a Wanderer came down their right wing I’d move up and crash him while the other fellows shifted over to cover my position. If the puck-carrier came down on my side I’d go up to check him as I would have naturally.” With forward passing against the rules at this time, “we stopped them cold.” The result was a tediously dull game, and though the Wanderers got the only goal, Ottawa took the series with a combined victory of 4–1.

Ross remembered that he and his teammates came up with their three-man defensive system while on the train from Ottawa to Montreal, but on the day of the game, The Ottawa Journal reported that Ross was already in Montreal (where he lived) when the rest of the Senators departed from the Capital. In reporting on the game in their Monday edition, The Journal repeatedly stated that the Senators were “acting under the instructions of Coach Alf Smith” in employing their defensive system. Ottawa had obviously been a strong defensive team all season, and it certainly makes more sense for their long-time coach to have devised their tactics rather than their newly signed defenseman, even if he was one of the game’s biggest stars. Yet over the years, legendary sportswriters Baz O’Meara and Elmer Ferguson would repeatedly credit (or blame) Ross for the development.

“Tracking back along the history of hockey,” Ferguson wrote in his syndicated column Inside Hockey in 1933, “it’s difficult to place the finger on a certain game or a certain date and declare that a new type of play started with that date, or with that game. But it is pretty safe to assert that on the night of March 13, 1915, there was born a young lady named “Kitty” who since has been a very bothersome factor in professional hockey. “Kitty, Bar the Door,” is her full name … [and] crafty Art Ross [devised] the play.”

By then, Ross had introduced many changes to the NHL rule book designed to improve offensive play, and his Bruins routinely boasted many of the league’s best scorers, yet the defensive reputation stuck to him. Perhaps that’s why he eventually donated the trophy that he did.

May 14, 2015

2015 Silver Birch Awards

The Silver Birch Awards ceremony was held in Toronto at the Harbourfront Centre on May 13. While I admit I would have liked to have won for “The Big Book of Hockey,” winning and losing isn’t really the point. The point is to get children excited about books, and they certainly seemed to be!

On stage with fellow nominees Stephen Shapiro and Hugh Brewster.

Signing autographs.

Reading from my Grade 5 newsbooks during a “Workshop.”

Annaleise Carr was the winner in my category for her book “Annaleise Carr: How I conquered Lake Ontario to help kids battling cancer.” She’s practically still a kid herself (only about 17) and swam the lake when she was 14. Pretty amazing … but her mother told me at an event a few days later in Whitby that Annaleise’s younger brother voted for my book!

May 12, 2015

The Bye Series of 1924

As a Canadian hockey fan, I was probably not alone as the second round got under way in thinking about the long-shot possibility of a Montreal-Calgary Stanley Cup Final. Definitely not a dream matchup for the NHL or NBC, but it would have been big up here north of the border! Calgary’s out now, but there’s still a chance for Montreal. We’ll know a little more about that tonight…

The Flames and Canadiens have met for the Stanley Cup twice already, back in the 1980s when Canadian teams were still reaching the Finals on a pretty regular basis. The Canadiens won in 1986 and the Flames won in 1989. But the first meeting of Calgary and Montreal for the Stanley Cup dates back 65 years before the Flames’ victory of 1989 to when the Canadiens swept the Calgary Tigers in a best-of-three Final in 1924.

For a brief period from 1922 to 1924, competition for the Stanley Cup was a three-league affair involving the NHL, the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, and the Western Canada Hockey League. In 1922, the PCHA champion Vancouver Millionaires defeated the WCHL champion Regina Capitals and earned the right to go east to face the Toronto St. Pats for the Stanley Cup. Toronto won. In 1923, Ottawa came west to Vancouver. They defeated the home team (now known as the Maroons) in a best-of-five series, and then defeated the Edmonton Eskimos in a best-of-three final to claim the Cup.

In 1924, Vancouver won the PCHA again and Calgary won the WCHL. Montreal won the NHL and, despite the arrangements in 1923, expected the western teams to send one winner east to play for the Stanley Cup as they had in 1922. Frank Patrick was in charge of both the PCHA and the Vancouver Maroons then, and he wrote about this in the final installment of an eight-part series about his life in the Boston Sunday Globe on March 18, 1935 while he was the coach of the Boston Bruins:

“I decided that both teams should come East to play Les Canadiens,” said Patrick. It was my idea that the Eastern fans would like to see both Vancouver and Calgary in action against the famous Canadiens.

“At first,” Patrick continued, “I thought we could toss a coin to decide which club would oppose Les Canadiens first. Then the thought occurred to me to play off for the ‘bye’ berth…”

Patrick got in touch with Calgary Tigers manager Lloyd Turner and made the arrangements. Calgary came west to Vancouver for game one of the series with game two played in Calgary. When both teams won on home ice in front of what Patrick recalled were capacity crowds, the best-of-three series was tied.

“Meanwhile, the National Hockey League in general and Les Canadiens in particular, were burning up. It was getting late in the season, it was a natural ice rink in Montreal with the danger of poor ice for the series, and Les Canadiens didn’t want to play two clubs anyway.”

Frank Patrick with his son Joe, circa 1927.

Vancouver and Calgary played their finale in Winnipeg on March 15, 1924, while en route east. Calgary won 3-1 in front of “another capacity house” to get the bye berth directly into the Stanley Cup Final. Vancouver would play Montreal in a semifinal, but NHL president Frank Calder and Canadiens boss Leo Dandurand were decidedly unhappy with the Western arrangement. They wondered, among other things, what right Vancouver would have (having already lost to the Tigers) to play Calgary for the Stanley Cup if they beat Montreal, and worried about who might show up for the Final if the hometown Canadiens weren’t in it! After a few days of squabbling, the western teams refused to back down and the NHL grudgingly agreed to the awkward format.

“When we arrived in Montreal,” Patrick recalled, “Leo Dandurand wouldn’t even speak to me. He staged a party for the Western clubs and invited everybody but me. Finally, after a couple of days, Leo weakened and ask me what we had played the bye series for. ‘For $20,000,’ I calmly replied. Then he laughed. He knew what I meant.”

What Patrick meant, of course, was the Western teams’ profits from the gate receipts of those three extra playoff games!

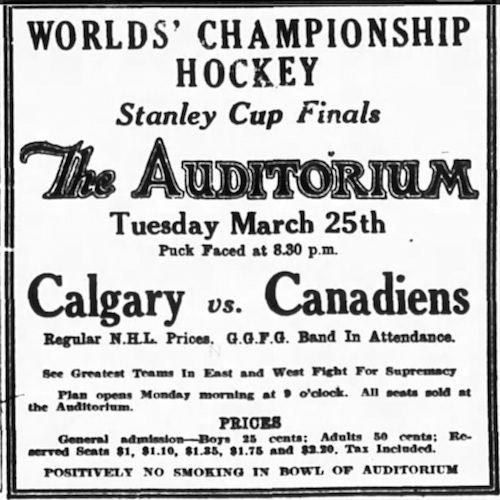

Having already swept Ottawa in two straight to win the NHL title, the Canadiens beat Vancouver in two and then took two in a row from Calgary to win the Stanley Cup … although warm, spring weather during the last week in March meant the final game on March 25, 1924, had to be moved from the natural ice surface of Montreal’s Mount Royal Arena to the artificial ice of the Ottawa Auditorium. Even so, a respectably large crowd for the era of 7,000 fans showed up.

Patrick had one more story to tell from the 1924 Stanley Cup Final, about Art Ross refereeing during the series. Ross tells the same story too, so it may even be true!

“At the end of the game in Ottawa, Charlie Reid, the Calgary goalie, skated up to Art and said: ‘As long as you’re refereeing the Stanley Cup will stay in the East.’ Quick as a flash Art came back: ‘Well, as long as you’re goal-tending, the Stanley Cup certainly won’t go West.”

May 6, 2015

Stanley Cup: Your Ad Here

My wife and I are both fans of the show “Elementary” which, if you don’t know, is a modern-day take on Sherlock Holmes in New York. Last week, the opening shot was a close-up on the inside of the rim of an elaborate bowl. To me, it was instantly recognizable, although I meant it as a joke when I said to Barbara, “It’s the Stanley Cup.” I actually thought it would be just an antique bowl, and I was curious to see how much it resembled the bowl atop the Stanley Cup. Then, they pulled back, and it was the real thing.

I’m not sure how this bit of product placement helps sell fans of TV mysteries on hockey, or helps sell hockey fans on this particular TV mystery (especially given that it runs on a network that doesn’t carry NHL games). And it didn’t really have anything to do with the plot, but it was still kind of neat!

As it happens, using the Stanley Cup to sell products that don’t always seem like a natural fit has been going on for a lot longer than you probably think. Almost since the very beginning of the Cup itself.

When the second edition of Total Hockey appeared in 2000, I had a story in it arguing that the 1896 Stanley Cup rematch between the Montreal Victorias and Winnipeg Victorias, played in Winnipeg on December 30 of that year, was the moment that made the Stanley Cup. Before the Winnipeg Vics came east to beat their Montreal counterparts on February 14, 1896, the Stanley Cup had hardly attracted any notice beyond the stretch of country from Toronto to Quebec City and was probably all but unknown to anyone but hard-core hockey fans. The win by Winnipeg, and the subsequent attention when Montreal challenged and won it back, made the Stanley Cup national news. Apparently, it also made it good sales copy.

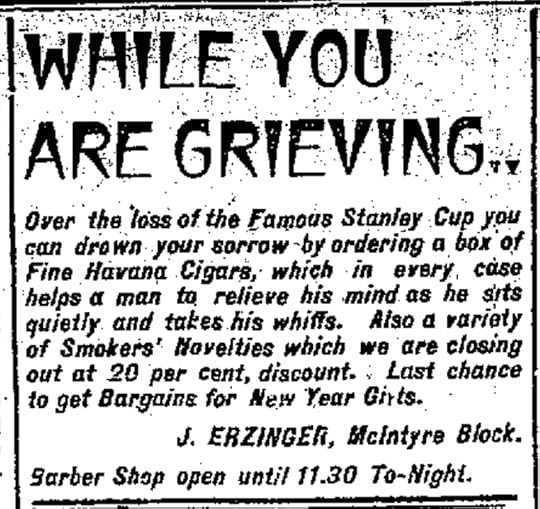

Presumably, J. Erzinger had a celebratory promotion planned if Winnipeg won, but here’s what appeared on page eight of the Manitoba Free Press on December 31, 1896, just a few hours after the hometown Victorias had been defeated:

It seems the idea of using the Stanley Cup to sell ones wares was more than good enough for James Henry Ashdown, the “Merchant Prince of Winnipeg.” With the Christmas season approaching, Ashdown ran a somewhat more on-topic ad in the Winnipeg Tribune on November 24, 1897:

So it would seem that more than 100 years before Winnipeg fans made “the whiteout” famous in the 1990s, certain citizens of the Manitoba capital were already capitalizing on their hockey heroes!

April 29, 2015

Boxing, Basketball and Hockey Too

This Saturday, Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao meet at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas in the most-anticipated boxing match in decades. The welterweights have long been considered the two best fighters in the world, and though boxing has certainly been in decline, the money for this bout is staggering. As champion, Mayweather will receive a 60-40 share of the purse that could net him as much as $180 million, win or lose. Pacquiao will have to get buy on a mere $120 million or so.

Something as simple as a broken finger from a bad bounce could have derailed the whole fight, but despite all the money on the line, Pacquiao, in the days leading up to his last fight in October, and as recently as early March while training for Mayweather, was playing basketball for the team he owns in his native Philippines.

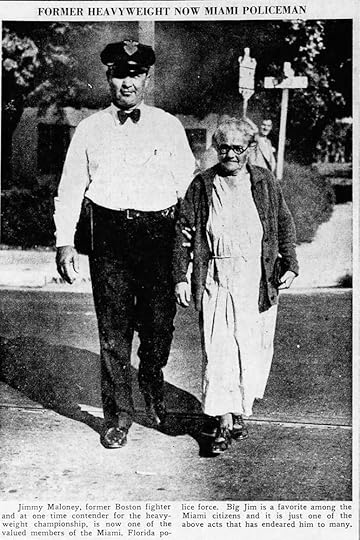

Beginning around 1924, Boston fighter Jimmy Maloney was a fairly successful heavyweight who fought against future champions Jack Sharkey (also of Boston) and Primo Carnera. In fact, Maloney was the first American boxer to beat Carnera during the Italian fighter’s first trip to the United States in 1930.

Art Ross had been known to step into the ring on occasion during his days as a hockey player, and as coach and GM of the Bruins, he allowed Maloney to hit the ice with his team in December of 1932 in a novel training technique that Pacquiao has emulated somewhat.

Maloney lost his next fight to Jose Santa on January 19, 1933, and certainly didn’t earn anything close to $120 million. He had a new manager by the end of 1933 – and probably wasn’t playing much more hockey – but lost what appears to be his last bout to Johnny Risko on January 9, 1934. Before the end of the year, Maloney was out of the fight game and working as a policeman in Miami. He later worked as a referee for boxing and wrestling matches. From what I can find on the internet, Maloney had a career record of 51-18-2 with 26 wins (and nine of his losses) by knockout. He died at the age of 68 on August 1, 1971.

April 22, 2015

Stanley Cup Anniversaries

This will come as little solace to Maple Leaf fans after, really, one of the worst seasons in franchise history. It’s now 48 years and counting since the team’s last Stanley Cup victory, and, yes, the fact that they haven’t even reached the Finals in that time, and have never really been a serious contender, makes it that much worse. But consider these various anniversaries the Stanley Cup marks this season:

100 years: It’s been that long since Vancouver won its one and only Stanley Cup in 1915, when the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association crushed the Ottawa Senators of the National Hockey Association in three straight games in their best-of-five series. But even that isn’t the longest Stanley Cup drought for a current NHL city. Winnipeg hasn’t won the big prize since 1902 – 113 years ago! – when the Victorias defeated the Toronto Wellingtons in January that year, before losing a challenge to the Montreal Hockey Club (aka the Montreal AAA) that March. They may be extreme long shots even to get out of the first round now, but at least the Jets and Canucks gave themselves a chance to end their cities’ Cup droughts this year. So did Ottawa, with an amazing 23-4-4 finish to clinch a playoff spot on the final day of the regular season … although it’s looking pretty unlikely that Senators will bring the Stanley Cup back to the Canadian capital for the first time in 88 years dating back to 1927.

100 years: It’s been that long since Vancouver won its one and only Stanley Cup in 1915, when the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association crushed the Ottawa Senators of the National Hockey Association in three straight games in their best-of-five series. But even that isn’t the longest Stanley Cup drought for a current NHL city. Winnipeg hasn’t won the big prize since 1902 – 113 years ago! – when the Victorias defeated the Toronto Wellingtons in January that year, before losing a challenge to the Montreal Hockey Club (aka the Montreal AAA) that March. They may be extreme long shots even to get out of the first round now, but at least the Jets and Canucks gave themselves a chance to end their cities’ Cup droughts this year. So did Ottawa, with an amazing 23-4-4 finish to clinch a playoff spot on the final day of the regular season … although it’s looking pretty unlikely that Senators will bring the Stanley Cup back to the Canadian capital for the first time in 88 years dating back to 1927.

75 years: When the New York Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1940, it marked their third championship in what was then the 14-year history of the franchise. It would be 54 years before they won it again in 1994, setting an NHL futility streak the Leafs seem to be aiming for. The Rangers haven’t won the Cup again in the 21 years since then, which means they’ve only won it once in 75 years! (Maybe twice by June.) Hey, Leafs fans, when you think of it that way, Toronto’s won the Cup 10 times in that stretch.

75 years: When the New York Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1940, it marked their third championship in what was then the 14-year history of the franchise. It would be 54 years before they won it again in 1994, setting an NHL futility streak the Leafs seem to be aiming for. The Rangers haven’t won the Cup again in the 21 years since then, which means they’ve only won it once in 75 years! (Maybe twice by June.) Hey, Leafs fans, when you think of it that way, Toronto’s won the Cup 10 times in that stretch.

45 years: It had a lot to do with a format that guaranteed an expansion team a place in the Finals, but the St. Louis Blues played for the Stanley Cup in each of their first three seasons in the NHL. They were swept in all three series, and since their last appearance in 1970, the Blues have never really come close. So, which is worse Leafs fans? No Stanley Cup wins since the last one in 1967, or none EVER since entering the NHL in 1967? (And the Vancouver Canucks and Buffalo Sabres haven’t won it either since they entered the NHL 45 years ago – which is pretty close to 48.)

45 years: It had a lot to do with a format that guaranteed an expansion team a place in the Finals, but the St. Louis Blues played for the Stanley Cup in each of their first three seasons in the NHL. They were swept in all three series, and since their last appearance in 1970, the Blues have never really come close. So, which is worse Leafs fans? No Stanley Cup wins since the last one in 1967, or none EVER since entering the NHL in 1967? (And the Vancouver Canucks and Buffalo Sabres haven’t won it either since they entered the NHL 45 years ago – which is pretty close to 48.)

40 years: They’ve come close a few times (as recently as 2010), but this year marks four decades since Philadelphia’s last Stanley Cup victory in 1975. In the grand scheme of things, how much worse is 48 years than 40?

40 years: They’ve come close a few times (as recently as 2010), but this year marks four decades since Philadelphia’s last Stanley Cup victory in 1975. In the grand scheme of things, how much worse is 48 years than 40?

25 years: After winning for the fifth time in a span of seven years during the team’s 11-year NHL history, it’s now been 25 years since the Edmonton Oilers won their last Stanley Cup in 1990. If you’re about my age, the Flyers drought and this one have got to make you feel old! At least fans in Edmonton will have Connor McDavid to make them feel better.

25 years: After winning for the fifth time in a span of seven years during the team’s 11-year NHL history, it’s now been 25 years since the Edmonton Oilers won their last Stanley Cup in 1990. If you’re about my age, the Flyers drought and this one have got to make you feel old! At least fans in Edmonton will have Connor McDavid to make them feel better.

Some other anniversaries of note:

90 years: The Stanley Cup victory by the Victoria Cougars in 1925 means it’s now been that long since the last non-NHL team won the Cup.

80 years: The Stanley Cup victory by the Montreal Maroons in 1935 is the last victory by an NHL team that no longer exists.

50 years: Montreal’s seventh-game victory over Chicago on May 1, 1965, marked the first time in hockey history that the Stanley Cup Finals stretched beyond April.

43 years: Me, with the mini-Cup I’ve had since 1972. It was part of a

whole set of mini NHL trophies from the Hockey Hall of Fame.

April 15, 2015

Blue Jays & Babe Ruth

I attended the Blue Jays’ home opener on Monday, running my streak to 39-for-39 in franchise history. (Even when they were rained out in 1980, I skipped my last class to attend the 4 pm first game two days later.) Of all the books I’ve worked on, my favorite would be when we did the Toronto Blue Jays Official 25th Anniversary Commemorative Book at Dan Diamond & Associates. It’s hard to believe it was so long ago.

Our book came out about the same time that HBO released 61*, which was directed by Billy Crystal. He talked a lot about what a thrill it was for him to tell this story of his childhood heroes. Well, Billy Crystal got to worship Mike Mantle, and Roger Maris, and Whitey Ford when he was a kid … but I’ve been watching for the ENTIRE HISTORY of the team I cheer for. Still, for this story, I’m borrowing from Billy’s team … though from a lot earlier than he remembers.

Recently, I came across Mark Truelove’s web site candiancolour.ca which displays digitally colourized historical Canadian photographs. It’s AMAZING. My only criticism is there aren’t enough pictures! (I imagine that’s because it takes time for him to do them so well.) The picture below is one of two on Mark’s site featuring Babe Ruth, and it got me wondering what he was doing on stage at the Pantages Theater in Vancouver on November 29, 1926.

On stage with Babe Ruth in Vancouver is mayor L.D. Taylor as catcher and

Chief of Police Long as umpire. For a larger image, see Mark’s web site.

For another original shot of Ruth on stage, see the Vancouver Archives.

Babe Ruth had had a terrible season by his standards in 1925. That was the year of “The Bellyache Heard ’Round the World” when he arrived at spring training horribly overweight and eventually spent several weeks in hospital with a stomach ailment that has never really been explained. Back in shape for 1926, Ruth rebounded to hit .372 with 47 homers and 146 RBIs.

The Yankees won the American League pennant in 1926, but Ruth made the final out in game seven of the World Series against St. Louis when he was caught trying to steal second base. At the time, this actually seemed to increase his popularity! (Ruth also hit four home runs in the series, including three in game four alone, when he may or may not have promised to hit one for hospitalized 11-year-old Johnny Sylvester, which didn’t hurt his popularity either!) After the series, Ruth went on a short barnstorming baseball tour before hitting the western vaudeville circuit.

On August 31, 1926, Ruth had signed a $100,000 contract with Alexander Pantages. Others had been bidding for his services too, but Pantages, via a long-distance telephone call from Los Angeles, blew them all away with the largest offer in the history of vaudeville. It was generally reported, then and now, that the deal was for 12 weeks, though some stories that fall claimed it was a 15-week tour. Either way, it was a ton of money for a player who’d just earned $52,500 for the six-month baseball season. (Ruth would hold out for $100,000 a year for two years prior to the 1927 campaign, and eventually signed for $70,000.)

Ruth’s Pantages tour opened in Minneapolis on October 30, 1926 and made its way west, winding up in California in February of 1927. He seems to have spent several days in most of the cities he visited. Basically, Ruth went on stage, recited a somewhat fictionalized story of his life, talked baseball, demonstrated his swing, and invited boys up with him for autographs. Bill Oram, writing in The Salt Lake City Tribune on July 11, 2011, quotes some of Ruth’s patter from his visit to the Utah capital in late January:

“Mr. Dunn made a pitcher out of me,” Babe Ruth relayed to his hungry audience. He was baseball’s best left-hander early in his career, and that started with the minor-league Baltimore Orioles under the watchful eye of manager Jack Dunn.

“Then he traded me the same day to another club for a batboy,” he embellished. “I was feeling pretty bad in the clubhouse that day when I thought it over. But I figured I could do Mr. Dunn a favor. I went to him and told him the ceiling was leaking in his clubhouse.”

The audience sat rapt.

Ruth paused for the punchline to his tale. “[Dunn] said, ‘You darn boob, that ain’t a leak. That’s the shower bath!’”

In an era when most people could only expect to see him in newsreels, Ruth charmed the crowds everywhere he went. In Vancouver, he had lunch with orphans at a Children’s Aid Society home and visited a disabled boy in hospital. This seems typical of most of his stops, and in some cities he even wrote a column (or, likely had it ghost-written) in local newspapers. Not everyone was enamored of his stage performance, however. Yankee biographers Jonathan Eig and Harvey Frommer both quote Ruth’s teammate Mark Koenig as calling his set, “boring as hell.” Sixteen-year-old Doris Bailey of Portland, Oregon (whose “Doris Diaries” have been published and appear online) thought Ruth was “not so much to rave about. Terribly conceited.”

Towards the end of the tour, Ruth was arrested in San Diego on January 23 because it was said that by calling up boys on stage with him so that he could sign autographs he had violated California’s Child Labor Laws! Regardless, kids stormed the stage in Long Beach the following night, and Ruth was later acquitted of the charges.

Before leaving California, Ruth lingered a little longer to film the movie Babe Comes Home, in which he plays a ballplayer whose love of a woman is threatened by his addiction to chewing tobacco. Soon after filming, Ruth signed his new contract with the Yankees, and though he got off to a slow start in 1927, he went on to hit .356 with 60 home runs and 164 RBIs (Lou Gehrig hit .373 / 47 / 175 and was named MVP) as the “Murders Row” team went 110-44 en route to winning the World Series.

April 8, 2015

Shore vs. Orr

As many of you reading this are already aware, I have a biography called Art Ross: The Hockey Legend who Built the Bruins due out this fall with Dundurn. Several stories that have appeared on my web site already have been the result of items I came across while researching Art Ross. More will be coming in the months leading up to the release in September, but this is the first real “commercial” for the book.

In March of 1970, Eddie Shore was in New York to receive the Lester Patrick Trophy for his contributions to hockey in the United States. He was presented with the award at Toots Shor’s Restaurant on the evening of March 9, 1970, but had held court with reporters at the Madison Square Garden press lounge during the afternoon. Shore was asked about the current star of the Bruins defense, Bobby Orr.

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on Facebook.

“I haven’t had that much chance to see Orr play,” Shore admitted. “But when I first watched him as a junior, I said he would be outstanding. He’s obviously a fine skater but I think the best thing about him is his ability to adjust his own speed to anticipate the speed of the players whom he is giving a pass.”

Those present wondered how Orr would have fared in Shore’s era, and somebody wondered if Shore had ever thought that a defenseman might win the NHL scoring title, as Orr was en route to doing.

“Yes, I believe one might have,” Shore said with a sly grin. “But maybe I shouldn’t really be specific.” Tom Fitzgerald, writing in the Boston Globe, noted that it didn’t take much urging for Shore to elaborate.

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

“Sure, I think I might have done it myself at least one year, but it would have cost me money. You see, when I carried the puck in, if I shot instead of passing, Art Ross had a standing fine of $500. It would have been too expensive.”

Ross had been dead for nearly six years at this time, so he wasn’t there to comment. Still, he’d told a very different type of story to Lester Patrick’s sons, Lynn and Muzz, back in 1958, which was reported by Dave Anderson, then of the New York Journal-American:

“When Leo Dandurand owned the Canadiens,” Ross explained, “he was in Chicago one night and we were there. So I invited him to sit down on the bench with me. After a while, I said to him: ‘Leo, would you like to see Shore score a goal?’ And he said: ‘What?’ So I asked him again. ‘Do you want to see Shore score a goal? I’ve got a signal.’ Without waiting for him to answer, I caught Shore’s eye and gave him the signal.”

Ross pointed his right forefinger, then rotated it clockwise; all the time holding his hand near his hip so as not to be conspicuous. Then he continued:

“Shore got the puck, took off, and wham! Goal! So Dandurand looked at me and said: ‘Can you do that anytime you want?’ ‘Sure,’ I told him, ‘and not only that, he’ll keep doing it until I tell him to stop.’ So, I caught Eddie’s eye again and give him a wave. That was the signal to stop. I didn’t want to overdo a good thing.”

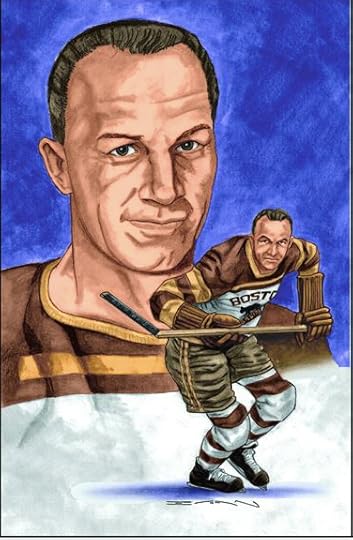

Photo courtesy of Art Ross III

Could either Shore’s or Ross’s tale be true? It’s difficult to say. Sportswriters for a long time rarely let the facts get in the way of a good story, and there’s little reason to believe the subjects of those yarns were any better!

April 1, 2015

Canucks Go For Pucks at Gonzaga

During the late 1980s, when I was at my most interested in NCAA basketball, I had a fondness for Gonzaga University. Partly that was because Gonzaga grad John Stockton was starring alongside Karl Malone with the NBA’s Utah Jazz, whom I also liked at the time. Admittedly, though, a big part of it was that I just liked to say, “Gonzaga!”

A couple of years ago, Canadian star Kelly Olynyk (now with the Boston Celtics) led Gonzaga to the top seed in the West Region at the NCAA tournament. Sadly, after a 31-2 regular season, the Zags (their actual nickname is the Bulldogs) went out in the second round. This year, with Canadians Kevin Pangos and Kyle Wiltjer, Gonzaga was 32-2 and were seeded second in the South. The Zags reached the “Elite Eight” for just the second time in school history, but were eliminated this past weekend by top-ranked Duke in the South Region Final and so failed to reach this weekend’s Final Four.

More than 75 years ago, Gonzaga used a Canadian connection to briefly become a West Coast hockey power. Coach and promoter Denny Edge ran Gonzaga’s hockey team. He was born in England, but raised in Regina, where he played junior hockey from 1918 to 1922, helping the Regina Pats reach the finals of the 1922 Memorial Cup. Edge played pro hockey in Los Angeles in 1926-27 and then managed the rink in Portland, Oregon until 1936 before moving to Spokane, Washington, to coach at Gonzaga.

Denny Edge wears the suit, Frank McCool wears the pads,

and Jerry Pettigrew stands on the right.

Edge tapped his home province of Saskatchewan for hockey players to take to Gonzaga – particularly the town of North Battleford. Future NHL goalie and executive Emile Francis was a young boy in North Battleford at the time and remembers the exodus of local talent. Jerry Pettigrew had led the North Battleford Beavers to the Allan Cup (Canadian amateur championship) Finals against Sudbury in the spring of 1937 before being recruited to Gonzaga that fall. Several other local boys made the trip with him and Gonzaga won the West Coast Amateur Hockey title in 1937–38. In their final game of the season they defeated the Big Ten champion University of Minnesota 5-1.

Edge added goalie Frank McCool of Calgary to the Gonzaga roster in 1938-39. McCool, later known as “Ulcers,” would famously win the Calder Trophy and the Stanley Cup with the Toronto Maple Leafs as an NHL rookie in 1944–45 while guzzling milk between periods to calm his roiling stomach. In his first of two seasons at Gonzaga, McCool led the team to the Pacific Northwest Amateur championship, a second straight West Coast Amateur title, and the Pacific Coast Collegiate championship.

James “Stocky” Edwards of Battleford, Saskatchewan isn’t a name most hockey fans will know. He was one of Canada’s leading air aces of World War II, but before that, Edwards played hockey at St. Thomas College, a Catholic high school in Battleford. He was small, but determined and very competitive. Barbara and I have visited with Stocky and his wife Toni several times before and after she wrote The Desert Hawk. He and I have talked hockey a bit, and I also had the chance to speak with Emile Francis about him.

Jim Edwards is on the right with brothers Paul (center) and Edd Ballandine.

It had been decades since Francis faced Stocky (or had even seen him) when Stocky was finishing up at St. Thomas and Francis was a freshman at North Battleford Collegiate. Still, he remembered him as an excellent shooter who would cut hard for the net from the right wing. “He didn’t take the ‘overland route,’” said Francis, who added that the first time he played against Howie Meeker of the Toronto Maple Leafs he thought, “This guy reminds me of Jimmy Edwards.”

Edwards was good enough that Johnny Gottselig of the Chicago Blackhawks arranged for him to have a tryout with the team. He also attracted the interest of Denny Edge, who recruited him for Gonzaga. Excited as he was by the NHL attention, Edwards planned to further his education at the Spokane University … but decided to join the RCAF instead. Edwards went on to a career in the Air Force, while Denny Edge’s powerhouse hockey program at Gonzaga University became a forgotten casualty of the Second World War.

March 25, 2015

Net Results…

Are bigger nets the answer to more scoring in the NHL?

The debate has come up from time to time since the end of the lockout that wiped out the entire 2004-05 season. Goalies these days are bigger than ever, and the NHL has made an effort to reduce the size of the equipment they use. Still, there seems to be little appetite for increasing the size of the nets from the 6-feet-by-4-feet they’ve always been since netting was first draped over metal posts in 1899. Tradition is often given as a reason in the arguments against enlarging the nets, but surprisingly, such talk dates back a lot further than people probably think.

With scoring in the NHL down considerably in 1926-27, sports editor Frederick Wilson of The Globe in Toronto noted in his column on February 21, 1927, a suggestion made in New York to widen the nets to seven feet. Nothing come of it, and scoring continued to drop, reaching an all-time low in 1928-29. Only 2.8 goals per game were scored on average that season by both teams combined, meaning the typical score was 2-1 in overtime. This is the year that George Hainsworth set records with 22 shutouts during the 44-game schedule and an average of 0.92. Every one of the NHL’s 10 starting goaltender had an average of 1.85 or better, and eight of them had at least 10 shutouts. More modern passing and offside rules were introduced in 1929-30, and offense jumped to over six goals per game. However, scoring dropped dramatically again in 1930-31, although it wasn’t nearly as low as it had been at its worst.

Even so, the Mercantile League in Toronto (which played out of the Ravina Rink, near Keele and Annette) was given permission by the Ontario Hockey Association and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association to experiment with nets that measured 7½ feet wide from January 28, 1931, until the end of its regular-season schedule in March. The new nets resulted in a few games with scores as wild as 10-5, but most were still 3-1 and 2-0.

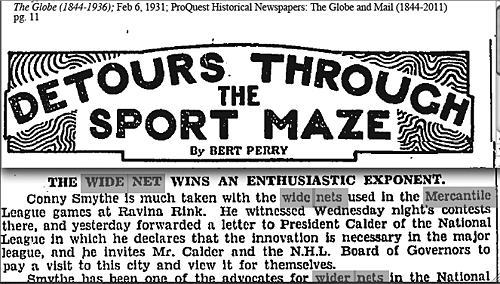

Maple Leafs boss Conn Smythe loved the wide nets. He wrote letters to NHL president Frank Calder and his fellow governors inviting them to Toronto to see for themselves. Smythe, Calder and Leo Dandurand attended a Mercantile league doubleheader on February 18, but Mike Rodden, writing in The Globe the next day, noted that the teams “proceeded to give their worst displays of the season.” (The games were 3-3 and 3-1, Rodden worked both as referee, and elsewhere in The Globe it was noted that they were marked by “exceptional goalkeeping.”) Calder and Dandurand were unimpressed, though the NHL president noted that the nets didn’t strike him as alarmingly wide.

Given the animosity between them, it’s entirely possible that Conn Smythe supported the wider nets simply because Art Ross had designed the ones the NHL had been using since 1927-28. (The Art Ross net would be used without change through the 1983–84 season, and all the new nets used since then are still just a variation of his original design.) The 6-by-4 size had been well established long before then, but Ross still became the go-to guy whenever talk of the nets came up. It’s unlikely he saw any of the wide-net games in Toronto in 1931, but he did give his thoughts on the experiment to Boston Traveler hockey editor Ralph Clifford. “Adhere to the rules,” Ross said. “Have them strictly enforced … and you will have a game that is wide open enough to satisfy the most exacting fan.”

Art Ross with sons Arthur (the goalie) and John. Courtesy of Art Ross III.

People don’t think of the heyday of Gordie Howe and Maurice Richard as a low-scoring era, but the 1952-53 season saw only 4.8 goals scored per game. Once again, people wondered about widening the nets. “Somebody brings that up every time the defense gets ahead of the offense for a while as it is right now,” Tom Fitzgerald quoted Ross as saying in the Boston Globe on November 28, 1953. “We’ve gone through a lot of different phases like this, and certainly the hockey has been interesting this season, even if fewer goals are being scored… Increasing the width of the nets a little wouldn’t boost scoring to any great extent.”

Speaking about scoring again a few days later, Ross said: “It’s pretty simple. The more you keep shooting at the net, the more chances you have to score. There are a lot of factors that are going to help if you pour enough shots at a goalie – deflections, funny bounces and the like. If you just keep shooting away the percentages will work out for you.”

But chances are, Art Ross never envisioned a game where players blocked shots like they do today, or one where goalies were so large, agile and well padded. He’d been involved with the game at its highest levels since 1905 as a star player and then an executive, but Ross never seemed to be bound by tradition. It would be interesting to see where he’d stand on enlarging the nets if he were alive today.