Peter Cameron's Blog, page 5

March 29, 2022

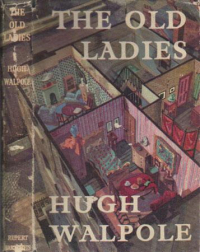

The Old Ladies by Hugh Walpole, George H. Doran Co., 1924...

The Old Ladies by Hugh Walpole, George H. Doran Co., 1924

An interesting and disturbing novel about three old ladies, all poor and alone, who live in three rented rooms on the third floor of an abandoned house in a provincial English city. Our hero is Mrs. X (already forgotten her name), a genteel widow who has fallen on hard times, and whose son Brand (remember his name!) has disappeared in America. Our villain is Mrs. Y (forgot her name, too), a fat, lazy, slovenly woman who is both a power-hungry sadist and a lover of brightly-colored and beautiful objects. Mrs. Z (name forgotten), the third old lady, moves into the cold, drafty house when she loses all her money to a silver-haired scam artist who tricks her into investing her small fortune with him. Goodbye small fortune! Her most precious remaining possession is a piece of golden-red amber given to her by her only friend, which Mrs. Y decides she must have, even if it means scaring poor Mrs. Z to death, which in fact it does.

An interesting and disturbing novel about three old ladies, all poor and alone, who live in three rented rooms on the third floor of an abandoned house in a provincial English city. Our hero is Mrs. X (already forgotten her name), a genteel widow who has fallen on hard times, and whose son Brand (remember his name!) has disappeared in America. Our villain is Mrs. Y (forgot her name, too), a fat, lazy, slovenly woman who is both a power-hungry sadist and a lover of brightly-colored and beautiful objects. Mrs. Z (name forgotten), the third old lady, moves into the cold, drafty house when she loses all her money to a silver-haired scam artist who tricks her into investing her small fortune with him. Goodbye small fortune! Her most precious remaining possession is a piece of golden-red amber given to her by her only friend, which Mrs. Y decides she must have, even if it means scaring poor Mrs. Z to death, which in fact it does.

It's interesting to read a book set entirely in the world of these disenfranchised and desperate elderly women, a type of character not often encountered in fiction, and even more rarely exclusively and in triplicate, even if their characters are broadly drawn and the action is melodramatic. Brand, Mrs X's long-lost son, returns to his mother in the nick of time, for at least one happy ending, but the strange and bitter taste of this macabre book lingers.

March 28, 2022

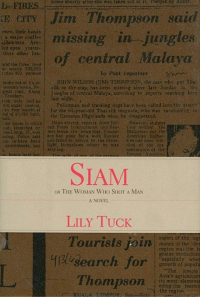

Siam, Or The Woman Who Shot A Man by Lily Tuck, The Overl...

Siam, Or The Woman Who Shot A Man by Lily Tuck, The Overlook Press, 1999

Lily Tuck is one of the few contemporary writers I am always excited to read, and Siam is yet another cool, elegant, and intelligent novel about women coping with personal dramas in foreign countries, where the personal and the political artfully merge (or collide).

This is the story of Claire, a young American woman who travels with James, her government/military contractor husband, to Thailand in 1966, where he is overseeing the construction of runways in the northern jungles to facilitate the bombing of Viet Nam. His frequent trips to the north leave Claire alone in Bangkok, in a house with a pool and several not-entirely cooperative servants. She becomes obsessed with the mysterious disappearance of Jim Thompson, the (real) American man who reinvigorated the Thai silk industry.

This is the story of Claire, a young American woman who travels with James, her government/military contractor husband, to Thailand in 1966, where he is overseeing the construction of runways in the northern jungles to facilitate the bombing of Viet Nam. His frequent trips to the north leave Claire alone in Bangkok, in a house with a pool and several not-entirely cooperative servants. She becomes obsessed with the mysterious disappearance of Jim Thompson, the (real) American man who reinvigorated the Thai silk industry.

The United States' corroding involvement in Southeast Asia is slowly and slyly revealed as Claire's activities and liaisons make her more aware of her own and her country's nefarious presence in the larger world. As always Tuck writes with stylish aplomb -- her view of the world, even seen through (or slyly around) Claire's rather deluded eyes, is always crystal clear and bracingly complex. Her writing is assured, sensual, and compelling. I'd read anything by her.

Albert Spears by Millen Brand, Simon and Schuster, 1947

...

Albert Spears by Millen Brand, Simon and Schuster, 1947

Another interesting and unusual novel by Millen Brand, written with his customary clarity and empathy. I discovered Brand's first novel, The Outward Room (1937), in a second-hand bookstore and convinced New York Review Books to republish it, with an afterword written by me, in 2010. (I also admire his second novel, The Heroes, published in 1939.)

The eponymous Albert Spears is 66 in 1915, and lives with his invalid and house-bond wife in Jersey City. (I wonder why Brand gave his hero the same name as the Nazi war criminal.) Albert has a son with his long-time mistress, a younger woman in the neighborhood, who he would like to adopt (the son not the mistress). He runs a carpentry mill and speculates in residential real estate and becomes involved in a local conflagration when a Black family moves into the all-white neighborhood. Albert befriends the family and attempts to make them feel welcome and safe, but his neighbors are united in their hateful prejudice and do everything they can to force the family to leave (break all their windows, sabotage their heat and water, send the father to jail). Albert's son also befriends the family, and fights along with the other Black boys when their gangs clash.

The eponymous Albert Spears is 66 in 1915, and lives with his invalid and house-bond wife in Jersey City. (I wonder why Brand gave his hero the same name as the Nazi war criminal.) Albert has a son with his long-time mistress, a younger woman in the neighborhood, who he would like to adopt (the son not the mistress). He runs a carpentry mill and speculates in residential real estate and becomes involved in a local conflagration when a Black family moves into the all-white neighborhood. Albert befriends the family and attempts to make them feel welcome and safe, but his neighbors are united in their hateful prejudice and do everything they can to force the family to leave (break all their windows, sabotage their heat and water, send the father to jail). Albert's son also befriends the family, and fights along with the other Black boys when their gangs clash.

Brand writes from the point of view of both families, from the perspective of the young and elderly of both races, and his creation of many complex and very different characters is admirable. An interesting and engaging look at race relations, and the power of individuals, in early 20th-century America.

Alice Neel and Millen Brand (foreground), 1966.

(Photograph by Jonathan Brand)

February 14, 2022

*Maybe Tomorrow by Jay Little (Pageant Press, 1952)

Ga...

*Maybe Tomorrow by Jay Little (Pageant Press, 1952)

Gaylord LeClaire ("Gay" for short) grows up in Cotton, a small town in Texas. By the time he's in High School, he realizes he is different from all other boys: he wishes he were a girl and is attracted to boys, particularly Bob Blake, the handsome, friendly, and charming captain of the football team. Fortunately, Gaylord is very attractive (albeit "pretty") and has a big dick, and although he is bullied and teased -- he's nearly raped in the locker room by a group of boys who call him a "Venus with a Penis" -- he is also befriended, rather suddenly, by Bob Blake (and his girlfriend Joy). It turns out that Bob is secretly gay and loves Gaylord, even if he calls him "my beautiful faggot."

Gaylord LeClaire ("Gay" for short) grows up in Cotton, a small town in Texas. By the time he's in High School, he realizes he is different from all other boys: he wishes he were a girl and is attracted to boys, particularly Bob Blake, the handsome, friendly, and charming captain of the football team. Fortunately, Gaylord is very attractive (albeit "pretty") and has a big dick, and although he is bullied and teased -- he's nearly raped in the locker room by a group of boys who call him a "Venus with a Penis" -- he is also befriended, rather suddenly, by Bob Blake (and his girlfriend Joy). It turns out that Bob is secretly gay and loves Gaylord, even if he calls him "my beautiful faggot."

Gaylord's parents (unwisely) take him to New Orleans for a weekend, where Gaylord is promptly taken underwing (and into bed) by a handsome and pleasant but unhappy homosexual named Paul. Paul takes Gaylord to a dive gay bay and then to a private party hosted by Gene, a mincing and shrieking queen, attended by an assortment of faggots, including Gus, a butch number who does a balletic striptease and tries to pry (literally) Gaylord from Paul's arms.

Although many gay men may have spoken and acted exactly like the "faggots" Gaylord encounters in the Big Easy, reading these scenes now is disturbing: one realizes this exaggerated, self-loathing behavior is a result of ceaseless ridicule, mental and physical harassment, and debilitating repression, and that the "inversion" of homosexuality is something that is forced upon homosexuals, not something that is innate. A tree grows thwarted and crooked only when it is prevented from growing as it naturally would.

Characters in pre-Stonewall gay novels are usually doomed to death and (self) destruction, but Jay Little gives all the gay characters in this book unusually happy endings: Bob and Gay decide to pack up and move to New Orleans as soon as they graduate from High School -- be careful, boys! --and Paul picks up a nice masculine married man who decides to never leave once he gets to Paul's tastefully decorated bachelor pad (complete with a goatskin on the bed). And Gaylord is an admirable character -- he is kind, honest, and loving. So in many ways, this book, while disturbing in its unnuanced and objectifying portraits of many of its gay characters, is a delightful anomaly in pre-Stonewall queer literature: a feminine boy is an admirable hero. He gets the football player, befriends the dimpled, hunky farmboy (a subplot), and lives happily ever after -- maybe tomorrow.

Jay Little in (above) and out of (below) drag. More photographs, and an interesting and well-researched examination of Jay Little and Maybe -- Tomorrow are featured on Brooks Peters' blog An Open Book.

The Bear by Marian Engel (McClelland and Stewart, 1976)

...

The Bear by Marian Engel (McClelland and Stewart, 1976)

A strange and disturbing novel about a young Canadian woman who leaves her solitary academic life working for a historical society in Toronto to catalog the contents of a house located on an island in a river in the Canadian wilderness. She lives alone in the house for the summer, and has an affair with a bear who had been kept in captivity there. The bear is an excellent lover, and the woman enjoys her solitary life and the bear's good company, but must leave this idyll life behind when autumn arrives and she is forced to return to her passionless urban life.

A strange and disturbing novel about a young Canadian woman who leaves her solitary academic life working for a historical society in Toronto to catalog the contents of a house located on an island in a river in the Canadian wilderness. She lives alone in the house for the summer, and has an affair with a bear who had been kept in captivity there. The bear is an excellent lover, and the woman enjoys her solitary life and the bear's good company, but must leave this idyll life behind when autumn arrives and she is forced to return to her passionless urban life.

Engel writes about the woman's relationship with the bear in a wonderfully matter-of-fact fashion, and the inter-species amour is believable and poignant (and quite erotic, as well).

*The Custard Boys by John Rae (Farrar, Straus $ Cudahy, 1...

*The Custard Boys by John Rae (Farrar, Straus $ Cudahy, 1961)

A short, intense, and disturbing novel about a gang of adolescent boys in a northern seaside village in England during WWII. It's narrated by John Curlew, the most decent and brightest of the boys. Excited by the war but feeling excluded from the action, the boys play at violent games that ultimately result in the shooting death of Mark Stein, an Austrian Jewish boy who has escaped Nazism only to encounter and be destroyed by England's more refined anti-semitism.

A short, intense, and disturbing novel about a gang of adolescent boys in a northern seaside village in England during WWII. It's narrated by John Curlew, the most decent and brightest of the boys. Excited by the war but feeling excluded from the action, the boys play at violent games that ultimately result in the shooting death of Mark Stein, an Austrian Jewish boy who has escaped Nazism only to encounter and be destroyed by England's more refined anti-semitism.

Rae is a good writer, although there is perhaps too much dark foreshadowing in the book -- it seems forced and strained and makes the book's shocking conclusion less surprising and potent.

The Early Life of Stephen Hind by Storm Jameson (Harper &...

The Early Life of Stephen Hind by Storm Jameson (Harper & Row, 1966)

The Early Life of Stephen Hind is a novel about a beautiful, charming, intelligent, and ambitious young man rising in society, set in London in 1963.

Stephen Hind's mother is a whorish clairvoyant and all he wants is to escape her tawdry and dirty world and become part of the upper class. A job as a secretary to Lord Chatteney, who is writing his memoirs, allows Stephen to enter this world, and his rise is swift: he becomes the boy toy of the elegant and accomplished Collette Hyde, who is married to the best publisher in London, enters a cordial marriage of convenience with a beautiful and wealthy women who is pregnant with a bastard, and sets his sights on a leggy Philadelphia steel heiress.

Stephen Hind's mother is a whorish clairvoyant and all he wants is to escape her tawdry and dirty world and become part of the upper class. A job as a secretary to Lord Chatteney, who is writing his memoirs, allows Stephen to enter this world, and his rise is swift: he becomes the boy toy of the elegant and accomplished Collette Hyde, who is married to the best publisher in London, enters a cordial marriage of convenience with a beautiful and wealthy women who is pregnant with a bastard, and sets his sights on a leggy Philadelphia steel heiress.

The main plot revolves around the completion and publication of Lord Chatteney's memoir -- he is considered a great man and his memoirs are heralded as a great work of literature. Both of these claims seem inflated to raise the stakes, but the novel is an entertaining and interesting look at a transitional time in England, when class distinctions were becoming more fluid and the old world was giving way to a more youthful culture.

February 7, 2022

Company Parade by Storm Jameson (Virago Modern Classics, ...

Company Parade by Storm Jameson (Virago Modern Classics, 1982, originally published by Cassell in 1934)

This novel, which was intended to be the first of a five- or six-book series that turned out to be a trilogy, is an ambitious and impressive achievement. I was engrossed by it and impressed by its scope and intelligence and the high quality of the writing and thinking that sustains it.

It's the story mainly of Hervey Russell, a young woman who comes to London soon after Armistice Day in 1918 to pursue fame and fortune as a novelist. She is disastrously married to a selfish, immature, and incompetent man named Penn who is still serving in thte army as the book begins. They have a son, Richard, who Hervey has left behind in another woman's (paid) care in her Yorkshire coastal hometown, so that Hervey is alone and independent in the city, qualities that make her an unusual female character from this period.

She's a unique and interesting character: kind, thoughtful, but socially-awkward and hampered by her wasted love for her husband and her estrangement from her son. She gets a job working for an advertising agency and later as an assistant editor at a radical newspaper, and moves about London's literary and publishing circles, which gives Jameson the opportunity to introduce and develop many interesting characters, which the narrative flexibly -- and sometimes messily -- embraces. I look forward to reading the next book in the trilogy, Love in Winter, which is followed by None Turn Back.

Good Behavior by Molly Keane (New York Review Books, 2021...

Good Behavior by Molly Keane (New York Review Books, 2021, originally published in by Andre Deutsch in 1981)

A dark, weird and disturbingly funny book with a gimmick that I felt reduces it to something smaller than its brilliant illparts. Aroon, the narrator, is an ungainly, very large, and rather obtuse girl growing up in an aristocratic but financially challenged Anglo-Irish family. Her mother is a heartless and abusive bitch, her father is benign but ineffectual, and her brother uses Aroon to unwittingly disguise his homosexual relationships.

Aroon sees and feels none of this ill-treatment and considers herself happy, well-loved, and fulfilled. Whether this is a result of repression and self-deception or merely stupidity is hard to know, but it begins to seem contrived and manipulative, and the book's effect is correspondingly diminished.

*Radcliffe by David Storey (Coward-McCann, 1964)

Radcli...

*Radcliffe by David Storey (Coward-McCann, 1964)

Radcliffe is a strange, densely-written book about the passionate and obsessive relationship between two men in the north of England. Leonard Radcliffe is the scion of an ancient aristocratic family who no longer have money and whose ancestral home, called The Place, is crumbling and derelict. It is now controlled by a trusteeship, and Leonard's father (John) works as the caretaker and lives with his family in the few remaining habitable rooms.

Radcliffe is a strange, densely-written book about the passionate and obsessive relationship between two men in the north of England. Leonard Radcliffe is the scion of an ancient aristocratic family who no longer have money and whose ancestral home, called The Place, is crumbling and derelict. It is now controlled by a trusteeship, and Leonard's father (John) works as the caretaker and lives with his family in the few remaining habitable rooms.

The novel follows Leonard Radcliffe from his early boyhood through his adolescence, when he first meets and connects with Vic Tolson, whose magnificent body seems to be mysteriously and symbiotically connected to Leonard's soul and mind. Radcliff reencounters Tolson as an adult and begins a tortured sexual and psychological relationship with him that ultimately kills them both.

Leonard Radcliffe is what today would be called "on the spectrum." He's a strange, solitary, non-communicative boy who grows into an even more troubled and antisocial man. His only affection and connection come from Tolson, and since their relationship is totally destructive and impossible, Radcliffe knows he will always be estranged and alone.

Storey unfolds this dark, gothic novel over 400 very densely-written pages. The third-person narrator is hyper-descriptive and psychologically analytical -- almost every sentence includes some sort of comparison using "as if" or "as though," all in an effort to describe the bizarre internal world of the character. It's a bad dream of a book, played out on a level of psychological abstraction that prevents the reader from identifying or sympathizing with Radcliffe (or any of the other characters). But realism is obviously not Storey's aim here, and the book's peculiarity, while often puzzling and distancing, makes for a reading experience unlike any other, and there is something commendably courageous about that.

Storey unfolds this dark, gothic novel over 400 very densely-written pages. The third-person narrator is hyper-descriptive and psychologically analytical -- almost every sentence includes some sort of comparison using "as if" or "as though," all in an effort to describe the bizarre internal world of the character. It's a bad dream of a book, played out on a level of psychological abstraction that prevents the reader from identifying or sympathizing with Radcliffe (or any of the other characters). But realism is obviously not Storey's aim here, and the book's peculiarity, while often puzzling and distancing, makes for a reading experience unlike any other, and there is something commendably courageous about that.

Peter Cameron's Blog

- Peter Cameron's profile

- 589 followers