Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 341-360 of 419

Peter @75: I have not read enough of Ovid in the original yet to know whether all the stories like Callisto's are so clearly framed as rapes. But I am a little surprised, since the Renaissance viewpoint that gave us all those pictures, operas, and other artworks, tends to be much more romantic.

Peter @75: I have not read enough of Ovid in the original yet to know whether all the stories like Callisto's are so clearly framed as rapes. But I am a little surprised, since the Renaissance viewpoint that gave us all those pictures, operas, and other artworks, tends to be much more romantic.You are absolutely right about the witty use of zeugma (or is it syllepsis?) in Ovid's account. I have looked at four English translations. All attempt something similar, but few succeed so well. Here (slightly longer) are the renderings by Garth, Humphries, Martin, and Miller (prose):

The God was wroth, the colour left his look,So yes, translators have noticed what Ovid did. But Latin is a so much more compressible language. R.

The wreath his head, the harp his hand forsook;

His silver bow and feather'd shafts he took,

And lodg'd an arrow in the tender breast,

That had so often to his own been prest.

The god lost countenance, and color also,

His laurel crown came sliding off his forehead,

He dropped his lyre, and, as his anger mounted,

He took the bow, he bent it, fired the arrow

Into the breast he had felt against his own.

The laurel resting on his brow slipped down;

in not as much time as it takes to tell,

his face, his lyre, his high color fell!

When that charge was heard the laurel glided from the lover's head; together countenance and color changed, and the quill dropped from the hand of the god.

Jim wrote: "WOW! Now THAT is operatic!"

Jim wrote: "WOW! Now THAT is operatic!"Thanks, Jim. I'm relieved that someone is reading these more off-topic things. I realize that I tend to stray in my postings from Ovid, through translations of Ovid, through historical responses to Ovid, to other artists (as here) revisiting his stories. But it is precisely this Protean fecundity that fascinates me about the collection.

As for staging it, I wouldn't. How could you match Walcott's images? But were I a composer, I would be sorely tempted. R.

Vit wrote: "Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:

Vit wrote: "Gods are ready to use any means… Depiction of Envy is precise and magnificent:Livid and meagre were her looks, her eye

In foul distorted glances turn’d awry; ..."

That is indeed magnificent! Is it the Garth/Dryden translation? R.

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the horns of Taurus..."

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the horns of Taurus..."You're right. The Met. serves as an alternative handbook to the natural world—expressed in human terms, which makes it so delightful! R.

And here is another EUROPA, a rather more difficult one, by James Merrill (1948):

And here is another EUROPA, a rather more difficult one, by James Merrill (1948):The air is sweetest that a thistle guards.The image of "cloud-whites on porcelain" in the final stanza makes me think of the bas-relief below by Giovanni Francesco Rustici, in storage in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is unusual among representations of the Europa story for several reasons: it is very early (1495), it is sculptural rather than a painting, and Jupiter is clearly already beginning to enjoy the fruits of his latest capture! R.

But the lean scholar, reading Buffon and Horace,

Shuts his brown book, marking the place with a flower

Picked from the fragrant riot below his terrace,

And the sea rings with doubloons and the blossoming words

Of no poet are cleanly about him in a loud shower.

Those feasts, the jubilant quince and bursting pear,

The Judas tree and page in the wind rinsed.

He watches the young laundress of the shore

With blueing and suds rear linen virginals

In sprays of gold, her cloths, white birds, careless;

She stands like any maiden loved by Zeus.

His murkiest deeds, night-thoughts that hammer him

Upon his bed, are charmed into the light,

As might on one day of each year at noon

All creatures of the midnight wake and fly

In a fine sport under the lavish sun

To greet once what they are least succored by:

His dark thoughts whirl until they fall unconscious,

And the warm noon stoops over them then, anxious,

Passionate— ah, the ceremony of rape!

Rape, though of no flesh, nor of mind indeed,

But of the eye, in gauzes negligent,

That, scorched by the flowering nostrils, overstreams.

Then sudden ease: beyong the straits, the climb

Ecstatic of cloud-whites on porcelain, while

Supinely through high morning like a girl

Innocence glides, dipping a wrist in time,

On a white bull of cloud, a full white belle

Smiling, a bridal in the wastes of pearl.

Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:

Here is a superb 1981 poem by Derek Walcott, entitled EUROPA, nicely balancing the idea of the celestial body with the rape myth told by Ovid:The full moon is so fierce that I can count the

coconuts' cross-hatched shade on bungalows,

their white walls raging with insomnia.

The stars leak drop by drop on the tin plates

of the sea almonds, and the jeering clouds

are luminously rumpled as the sheets.

The surf, insatiably promiscuous,

groans through the walls; I feel my mind

whiten to moonlight, altering that form

which daylight unambiguously designed,

from a tree to a girl's body bent in foam;

then, treading close, the black hump of a hill,

its nostrils softly snorting, nearing the

naked girl splashing her naked breasts with silver.

Both would have kept their proper distance still,

if the chaste moon hadn't swiftly drawn the drapes

of a dark cloud, coupling their shapes.

She teases with those flashes, yes, but once

you yield to human horniness, you see

through all that moonshine what they really were,

those gods as seed-bulls, gods as rutting swans

an overheated farmhand's literature.

Who ever saw her pale arms hook his horns,

her thighs clamped tight in their deep-plunging ride,

watched, in the hiss of the exhausted foam,

her white flesh constellate to phosphorous

as in salt darkness beast and woman come?

Nothing is there, just as it always was,

but the foam's wedge to the horizon-light,

then, wire-thin, the studded armature,

like drops still quivering on his matted hide,

the hooves and horn-points anagrammed in stars.

Kalliope wrote: "Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting..."

Kalliope wrote: "Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting..."There is also the even more daring painting by Courbet (which I won't reproduce) in the Orsay, called something like "The Origin of the World."

But is it a different theme? Literally, of course. But one also feels that these myths arose as ways of explaining difficult things, and same-sex attraction is surely one of them. R.

Substantial indeed, Kalliope—wow! Was Beckmann's art eventually classed as degenerate?

Substantial indeed, Kalliope—wow! Was Beckmann's art eventually classed as degenerate?I repeat my earlier remark about serendipity. You have this apparent knack of synchronizing you seminars to whatever we shall be discussing, but in advance! R.

Jim wrote: "I cannot believe for a moment that Jove's selection of a bull as disguise in the original Europa store (upon which Ovid based his account) was anything less than a ribald story-teller's choice…"

Jim wrote: "I cannot believe for a moment that Jove's selection of a bull as disguise in the original Europa store (upon which Ovid based his account) was anything less than a ribald story-teller's choice…"Well maybe. But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud? R.

One more pictorial query:

One more pictorial query:

Above are three details, from Titian's Rape of Europa, Boucher's Jupiter and Callisto, and Rubens' Assumption of the Virgin. What is it with all these Cupids, putti, amoretti, or whatever else you want to call them? Isn't it interesting that Renaissance and later painters turned to the same symbols to show divinity, regardless of whether it was of the Christian or pagan kind? R.

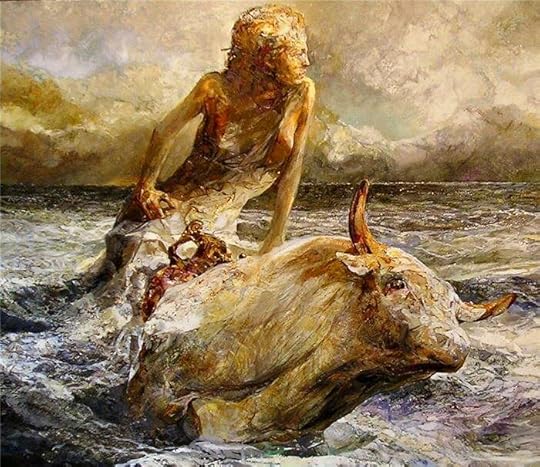

I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the name of the artist, Sergey Petrov Vasil Ustyuzhanin, and even that may not be accurate,

I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the name of the artist, Sergey Petrov Vasil Ustyuzhanin, and even that may not be accurate,

What I like about it, apart from the energy of the painting of the bull and the waves, is the figure of Europa herself. Unlike almost any of the more famous versions, she does not look either enamored, thrilled, or terrified. In fact, it is impossible to tell just what she is feeling. And given our current discussion about the morality of Ovid (or rather, the moralities we read into Ovid), I find this ambiguity stimulating. R.

Of your paintings, Kalliope, the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him break through the actual ceiling. It may be the first Jordaens that did not have me comparing him unfavorably to his master.

Of your paintings, Kalliope, the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him break through the actual ceiling. It may be the first Jordaens that did not have me comparing him unfavorably to his master.On the other hand, while Moreau is an interesting figure, I have never really liked any of his paintings, finding them too complex to make out exactly what is going on, and far too overperfumed. R.

Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that. Cavalli and Faustini, his librettist, have us sympathize with Calisto throughout, but give her a series of emotions:

Further to the above. I posted on Cavalli's opera La Calisto in comment #10, making the point that his Calisto, unlike Ovid's, delighted in her initiation. But it is more complex than that. Cavalli and Faustini, his librettist, have us sympathize with Calisto throughout, but give her a series of emotions:• rage against Jove for his scorching of the earthHow many of these occur in Ovid? Not the middle ones, because Jove reveals his manhood sooner. But what a marvelous roller-coaster of the emotions Cavalli provides! R.

• angry rejection of his sexual approaches when in his own form

• grateful pleasure when he woos her as Diana

• ebullient gratitude when she next sees the real Diana

• devastation when Diana throws her out

• touching trust when Juno draws her out

• speechlessness when Juno turns her into a bear

• radiant love when Jove sets her in the heavens

Kalliope wrote: "I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals...."

Kalliope wrote: "I prefer to stay within the analytical approach and stay away from the morals...."I know what you mean. As CS Lewis discussed in An Experiment in Criticism, it is a very limiting response to look at a work of art primarily in terms of our prior biases and experiences, and a very weak kind of art that encourages us to do so. We look to art to challenge, not to confirm.

On the other hand, it is quite possible to be objectively analytical in tracing the historical responses to a given theme. If we can demonstrate that a writer, painter, or composer of, say, the 17th century had a certain view of a subject, it is immaterial whether it matches our own, but quite legitimate to compare it with those of his processors, contemporaries, and successors. R.

Jim wrote: "The Mandelbaum version says it all ..."

Jim wrote: "The Mandelbaum version says it all ..."For those of us that are reading other translations, can you possibly quote a few lines of the Mandelbaum?

In recompense, I attach a few more from Ted Hughes, whose Tales from Ovid I have already quoted in message #12. What I like, that I don't find in any of the more formal verse translations that I have seen, is his willingness to abandon regularity of meter.*

Now Phaethon saw the whole world*Though I have just looked at the Rolfe Humphries, which I have on Kindle, and see that, even within a regular line-length, he manages a quite effective sense of disarray; he may well be even better:

Mapped with fire. He looked through flames

And he breathed flames.

Flame in, flame out, like a fire-eater.

As the chariot sparked white-hot

He cowered from the showering cinders.

His eyes streamed in the fire-smoke.

And in the boiling darkness

He no longer knew where he was

Or where he was going.

He hung on as he could and left everything

To the horses.

And Phaethon sees the earth on fire; he cannot

Endure this heat, the blast of some great furnace.

Under his feet he feels the chariot glowing

White-hot; he cannot bear the sparks, the ashes,

The soot, the smoke, the blindness. He is going

Somewhere, that much he knows, but where he is

He does not know. They have their way, the horses.

Jim wrote: "As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic..."

Jim wrote: "As we progress, I'm finding it a bit surprising that the "elephant in the room", namely sexual politics has not emerged as a major topic..."As Roman Clodia says, Jim, there have been a number of comments. For example, a couple of messages before your last one in Book I, I wrote something very similar to what you said just now:

One of the things that I find fascinating in this discussion is the way that sexual politics keeps shifting. We tend to assume that the moral code which we have evolved can be applied retrospectively to previous eras. But these issues, too, need to be viewed in the context of their time (whether Ovid's or that of the 16th century painters and composers), which is a much more slippery matter.I also engaged on a long discussion a bit earlier with Roman Clodia and others about the morality of the Daphne episode, finally conceding that my more indulgent attitude was probably not justified. But I agree: this is something that I would expect to be taken up by many people, and probably to elicit many points of view.

As you may have gathered, my own interest in Ovid now focuses on the further metamorphoses of his stories in the hands of the post-Renaissance artists, poets, and musicians who have been the furniture of my professional life. And whatever the attitude towards female autonomy in first-century Rome, there is little doubt that most retellers of the stories in the 16th through 18th centuries took a more romantic view at odds with the modern morality of #MeToo. I cannot think of many offhand that did not treat the visitations of Jove as a bit naughty, perhaps, but still a privilege for the nymphs concerned.

Juno's punishments, on the other hand, are almost always treated as being cruel, vindictive, and entirely unfair. R.

I especially like the Elsheimer, and so early too! In my own selection, what I like about the Fragonard, despite the terminal insipidity of the figures, is the way the moon is made a part of the landscape, rather than just a hair ornament as in the others. R.

I especially like the Elsheimer, and so early too! In my own selection, what I like about the Fragonard, despite the terminal insipidity of the figures, is the way the moon is made a part of the landscape, rather than just a hair ornament as in the others. R.

The Rape of Lucretia by Benjamin Britten is one of his less frequently seen but most interesting operas; I have done three productions of my own, and read most of the sources in that conneciton. The libretto by Ronald Duncan goes into the themes you mention, of course, but adds two more. One is Lucretia's guilt—not that she did not resist the rape (she did), but because she was fascinated by Tarquinius before this. "In the forest of my dreams," she tells him, "you have always been the tiger."

The Rape of Lucretia by Benjamin Britten is one of his less frequently seen but most interesting operas; I have done three productions of my own, and read most of the sources in that conneciton. The libretto by Ronald Duncan goes into the themes you mention, of course, but adds two more. One is Lucretia's guilt—not that she did not resist the rape (she did), but because she was fascinated by Tarquinius before this. "In the forest of my dreams," she tells him, "you have always been the tiger."But the oddest introduction is that of two Choruses, male and female, who comment on the action from the point of view of Christians. Not a classical attitude at all, and dramatically problematic. But those very problems are what makes it such a wonderful work to think about and to stage. R.

One of the things that I find fascinating in this discussion is the way that sexual politics keeps shifting. We tend to assume that the moral code which we have evolved can be applied retrospectively to previous eras. But these issues, too, need to be viewed in the context of their time (whether Ovid's or that of the 16th century painters and composers), which is a much more slippery matter. R.

One of the things that I find fascinating in this discussion is the way that sexual politics keeps shifting. We tend to assume that the moral code which we have evolved can be applied retrospectively to previous eras. But these issues, too, need to be viewed in the context of their time (whether Ovid's or that of the 16th century painters and composers), which is a much more slippery matter. R.

Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much

Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so muchI might as well post the great Titian painting of Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy, one of the seven "poesies," or scenes from Ovid, painted for Philip II of Spain. And with it, the Rubens version of the same subject, painted for Philip IV, around 80 years later. Both represent what might be called the "heroic" treatment of the subject—though cynics might think it is simply an excuse to paint female nudes.

Titian: Diana and Callisto (1556–59, Edinburgh NG)

Rubens: Diana and Callisto (c.1635, Madrd, Prado)

With the earlier episode of the story, Callisto's seduction by Jupiter, we are in a different ballpark. Rubens painted a version that, if not heroic (how could it be?), is certainly strong. François Boucher's 1759 painting has almost the strength of Rubens, but his other versions and those by other artists of the rococo era seem to aim instead for prettiness. The same cynics might say that Jupiter's change of gender gave perfect cover for erotic titillation of a rather different kind. R.

Rubens: Jupiter and Callisto (1615, Kassel)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1759, Kansas City)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1744, Moscow, Pushkin Mus.)

Boucher: Jupiter and Callisto (1763, New York Met)

Fragonard: Jupiter and Callisto (1755, Angers)

Angelica Kauffmann (attrib.): Jupiter and Callisto (late 18th century)