Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 281-300 of 419

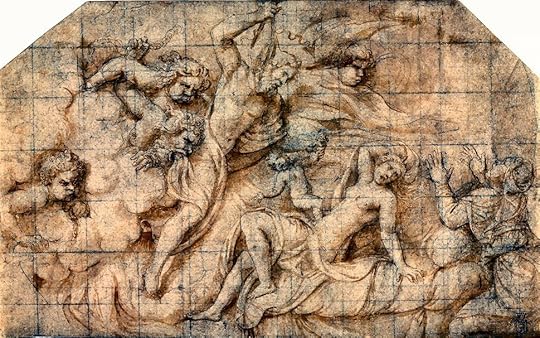

The Getty also has a Giulio Romano cartoon (drawing marked out as a guide for later scaling up) of the same subject. I give it below in two versions: untouched, and Photoshopped for greater contrast.

The Getty also has a Giulio Romano cartoon (drawing marked out as a guide for later scaling up) of the same subject. I give it below in two versions: untouched, and Photoshopped for greater contrast.

As you see, it is for an area of a different shape, which I find a lot more satisfactory. For one, there are fewer figures, and the main account is clearer. I also like the use of those heads in the clouds—not the usual pretty Cupids, but more like Winds in old maps. I admit, though, that the Bacchus flying from Semele to Jupiter is much older than a newborn, let alone a fetus! R.

HANDEL. There are several sound recordings of Handel's Semele. Although theoretically not an opera but a dramatic oratorio, it has also received many stage productions. All the ones I can find on YouTube, however, are given in modern dress; most are played more for comedy than Handel might have recognized.

HANDEL. There are several sound recordings of Handel's Semele. Although theoretically not an opera but a dramatic oratorio, it has also received many stage productions. All the ones I can find on YouTube, however, are given in modern dress; most are played more for comedy than Handel might have recognized.The links below are to two complete productions; there are several more out there. These are followed by four individual scenes, which offer a quicker way to sample the opera. In all cases, the text is in English.

• Complete production (2018) from the Komische Oper, Berlin. This staging by the Australian director Barrie Kosky is unexpectedly dark and unabashedly overacted.

• English National Opera (1999), Act I. A not very clear video of a good modern-dress production.

• ENO, Act II.

• ENO, Act III.

======

• "Endless pleasure, endless love." Cecilia Bartoli (entering at 3:13). Zurich, 2007. Semele's love life is worth singing about!

• "Iris, hence away." A wonderfully comic scene from the ENO production, in which Juno (here setting out to wreak revenge) is treated suspiciously like Queen Elizabeth II.

• "Myself I shall adore." From the ENO poduction. In the opera, the disguised Juno gets Semele to look at herself in a mirror—which, as we know from countless cautionary tales, is always a woman's downfall!

• "No, no, I'll take no less!" Cecilia Bartoli, as above. Her angry demand that Jupiter prove who he really is.

HUGHES. Here is the finale to the Semele story in the Ted Hughes version. Although still relatively short, he does produce rather more fireworks than Ovid himself.

HUGHES. Here is the finale to the Semele story in the Ted Hughes version. Although still relatively short, he does produce rather more fireworks than Ovid himself.Her eyes opened wide, saw himHughes is having a bit of blasphemous fun, I think, with the "Son of the Father" epithet! R.

And burst into flame.

Then her whole body lit up

With the glare

That explodes the lamp—

In that splinter of a second,

Before her blazing shape

Became a silhouette of sooty ashes

The foetus was snatched from her womb.

If this is a true story

The babe was then inserted surgically

Into a makeshift uterus, in Jove's thigh,

To be born, at full term, not from his mother

But from his father—reborn. Son of the Father.

And this was the twice-born god—the god Bacchus.

Kalliope wrote: "And then Semele's strong body, in all its 'Michaelangelesque' form ought to be able to withstand the somewhat diminished Jove"

Kalliope wrote: "And then Semele's strong body, in all its 'Michaelangelesque' form ought to be able to withstand the somewhat diminished Jove"Diminished? Depends upon your standard of comparison! R.

This one is too splendid not to post! Presumably it is the last appearance of Jupiter to Semele, in his full grandeur as a god. R.

This one is too splendid not to post! Presumably it is the last appearance of Jupiter to Semele, in his full grandeur as a god. R.

Sebastiano Ricci: Jupiter and Semele. 1695. Florence, Uffizi.

SEMELE: FOUR QUESTIONS.

SEMELE: FOUR QUESTIONS.1.Semele is pregnant by Jupiter, and yet he still visits her. I thought (without checking) that most of his amours were one-night-stands or close to it, but here is an actual relationship. Are there others?

2. In what form, then, did Jupiter come to Semele the first few times? As more or less a normal man, though telling her his name? It is a nice balance: too plain, and she wouldn't accept him (for there is surely no reason to think she was in the habit of sleeping around); too godlike, and she wouldn't be prey to Juno's temptation.

3. Given Ovid's skill as a dramatist, I am surprised that the denouement of this story is so comparatively flat. Jove returns in his own form; she cannot take it; he takes the infant Bacchus in his thigh; sooner or later, the child is born—all this in under ten lines. I rather think that Ted Hughes makes a lot more of this, but need to go home to check it.

4. Anyone else notice the parallel between Semele and Phaëton? To paraphrase TS Eliot, "Humankind cannot bear too much divinity."

I will post links to the Handel opera, perhaps a comment on the Hughes, and at least one painting later in the day. R.

I knew you would have helpful answers to my query, Roman Clodia! Thank you. Now you mention its poetic legacy, I agree with you about the Daphne story. I also take your implication that the fecundity of a trope has much to do with its fungibility, or as you say, its ability to be "developed, twisted, and renewed."

I knew you would have helpful answers to my query, Roman Clodia! Thank you. Now you mention its poetic legacy, I agree with you about the Daphne story. I also take your implication that the fecundity of a trope has much to do with its fungibility, or as you say, its ability to be "developed, twisted, and renewed."In the post below that, you also remind us of the significance of Ovid's myth as political commentary. Though there are some others here who share your knowledge, I am afraid that few general readers have the knowledge of history to read Ovid in this way, so once again your reminders are welcome. Roger.

Kalliope wrote: "The pictorial repertoire seems endless. Another winner—like Europa."

Kalliope wrote: "The pictorial repertoire seems endless. Another winner—like Europa."Late last night, I added a slightly tongue-in-cheek post (#71) to the General Chat section of the group. I was suggesting that we could rate the various stories on their fecundity factor: the degree to which they have inspired illustrations and other retellings in later centuries. More seriously, I asked why some should be more pervasive than others.

Europa and Actaeon, as you say, are winners in this regard. If we confine ourselves to painting, then one obvious reason is the excuse they give for portraying nudes or sexually suggestive scenes. But when they give rise to other poetry, to music, and to versions in other arts, then the pictorial possibilities alone do not explain the popularity.

Just for these two: I had heard the story of Europa way, way back; but I did not know the details of Actaeon until I had to direct the opera. Now I am wondering why. Roger.

Kalliope wrote: "It is interesting to see to which of the two aspects, the nude or the hunt does the painter give more attention."

Kalliope wrote: "It is interesting to see to which of the two aspects, the nude or the hunt does the painter give more attention."I thought that question was obvious: to the nudes! There are certainly some who have given as much or more attention to the landscapes (such as the Gainsborough or the Corot), but do you really know of any who have emphasized the hunt when there are naked women around?

Thank you for posting the Gérôme; I did not know it at all. Once again, the nudes are what it is all about, but the image of the hounds coming down the hill is a real invention. You don't see Actaeon spying, though, do you? And for that, he would need to be separated from the rest of the hunt. R.

As we progress slowly through the fifteen books, it might be fun to assign each story a fecundity factor, based on the strength and variety of their later progeny. Some of the stories have entered the popular imagination, and are known by people who have never heard of Ovid. Some may be less well known, but have nonetheless inspired numerous pictorial representations or versions in other media down the centuries. Some exist only between the cracks of the big stories, interesting while we read them, but without the same kind of resonance.

As we progress slowly through the fifteen books, it might be fun to assign each story a fecundity factor, based on the strength and variety of their later progeny. Some of the stories have entered the popular imagination, and are known by people who have never heard of Ovid. Some may be less well known, but have nonetheless inspired numerous pictorial representations or versions in other media down the centuries. Some exist only between the cracks of the big stories, interesting while we read them, but without the same kind of resonance.A more serious question would be to ask why this should be so. I suspect it has little directly to do with Ovid, more a matter of why the myth sprung up in the first place, what great truth it attempts to explain. Or maybe some stories are simply more entertaining than others? Roger.

TWO MORE. Two more later Cadmus pictures, and then I am done. After all that Northern bloodshed, I like the French elegance of the victorious Cadmus in the Blanchet painting receiving Minerva's suggestion that he sow the dragon's teeth. Zuccarelli was an Italian who settled in England and was elected to the Royal Academy; hence his presence in the Tate. His picture is an Arcadian landscape in the tradition of Claude, with the mythological subject very much secondary. R.

TWO MORE. Two more later Cadmus pictures, and then I am done. After all that Northern bloodshed, I like the French elegance of the victorious Cadmus in the Blanchet painting receiving Minerva's suggestion that he sow the dragon's teeth. Zuccarelli was an Italian who settled in England and was elected to the Royal Academy; hence his presence in the Tate. His picture is an Arcadian landscape in the tradition of Claude, with the mythological subject very much secondary. R.

Thomas Blanchet: Cadmus and Minerva, c.1680.

Francesco Zuccarelli: Landscape with the Story of Cadmus, 1765. London, Tate.

CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. Kalliope posted a painting by Hendrik Goltzius. Here are three of his engravings from earlier in the story, and a painting (or ink drawing) that prepares for his print of Cadmus's actual attack. I find the last four quite splendid in their depiction of the dragon, and the balance between man and monster really terrifying. [I am not sure of the accuracy of all this information; Google Image Search is an imperfect tool.] R.

CADMUS BY GOLTZIUS. Kalliope posted a painting by Hendrik Goltzius. Here are three of his engravings from earlier in the story, and a painting (or ink drawing) that prepares for his print of Cadmus's actual attack. I find the last four quite splendid in their depiction of the dragon, and the balance between man and monster really terrifying. [I am not sure of the accuracy of all this information; Google Image Search is an imperfect tool.] R.

Cadmus asking the Delphic Oracle about Europa.

The dragon attacking the companions of Cadmus.

The dragon devouring the companions of Cadmus. This is a copy of the 1588 painting by Cornelius van Haarlem now posted at comment 3/232.

Cadmus attacking the dragon (tinted drawing).

The engraved version of the above.

OLDER CADMUS IMAGES. Here are three older images of the Cadmus story. The krater image is from Wikipedia, and is rather splendid, though the dragon is not very fearsome. The Etrucsan relief is a lot more scary. I do rather like the Italian one, though, with the rather sweet toy dragon at right and the two youths on the left looking entirely unconcerned! R.

OLDER CADMUS IMAGES. Here are three older images of the Cadmus story. The krater image is from Wikipedia, and is rather splendid, though the dragon is not very fearsome. The Etrucsan relief is a lot more scary. I do rather like the Italian one, though, with the rather sweet toy dragon at right and the two youths on the left looking entirely unconcerned! R.

Calix krater, 4th century BCE. Paris, Louvre.

Etruscan chest from Volterra, 2nd century BCE.

Verona, 15th century.

I liked the Atwood, but enjoyed Zachary Mason's

The Lost Books of the Odyssey

at least as much; the link is to my review.

I liked the Atwood, but enjoyed Zachary Mason's

The Lost Books of the Odyssey

at least as much; the link is to my review.But now I see that Mason has applied his technique of literary repurposing to Ovid in his latest collection Metamorphica. I glanced only at one page online, a version of the Pygmalion story in which Galatea comes alive while the sculptor is asleep, leaving only chips of marble on the floor and wet footprints leading out into the garden. But the artist is philosophical. After all, she wasn't quite perfect, he thinks, and there are plenty more blocks of marble out there.… R.

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing."

Jim wrote: "I've not yet discovered how to post pictures here on Goodreads as several of you have been doing."Kalliope's approach is undoubtedly the simplest. I, however, copy the pictures first to my own website, where I can edit, crop, or combine them, and know that they won't suddenly disappear. R.

HUGHES/MATTHEWS. I looked up the Ted Hughes translation of the Actaeon story from his Tales from Ovid. It is lively but fairly straight, so I wasn't going to mention it.

HUGHES/MATTHEWS. I looked up the Ted Hughes translation of the Actaeon story from his Tales from Ovid. It is lively but fairly straight, so I wasn't going to mention it.But then I came upon this: a chamber music piece (2012) by David Matthews, in which the Hughes poem is beautifully read by Eleanor Bron, against and between passages of dramatic and highly expressive music. Even if only for the reading, I recommend it. R.

https://youtu.be/Wb-kAYraiqU

TITIAN 2012. Here is a short promo that I came across from the festival "Metamorphosis: Titian 2012," a collaboration between London's Royal Ballet and National Gallery. I have not looked to see what else may be there, but there are some fascinating threads to pick up. Roger.

TITIAN 2012. Here is a short promo that I came across from the festival "Metamorphosis: Titian 2012," a collaboration between London's Royal Ballet and National Gallery. I have not looked to see what else may be there, but there are some fascinating threads to pick up. Roger.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVgaK...

Jim wrote: "Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, ..."

Jim wrote: "Roger, I would be interested to learn about your approach to staging the opera. Perhaps as a means of avoiding the awkward necessity of presenting Diana and her nymphs in all their glowing nudity, ..."Thanks for asking, Jim. Did you look at the link I sent? Glowing nudity indeed—or it would be glowing, had the lighting been brighter. The other version on YouTube, by Les Arts Florissants, dresses the women in modern gowns and moves them in decorous ways among the orchestra; the Nymph who sings the aria about forswearing love (Arthébuze) indicates that she is bathing by removing one shoe!

I think my production (I realize now that I largely entrusted the second one to its choreographer) was very like what you describe. It was part of a program of one-acts by Monteverdi, Charpentier, and Purcell called "Pastorale and Masque," and was given in the court of the Walters Art Museum under a magnificent statue of Apollo, over twice normal scale. In a more mundane setting, I might have flirted with apparent nudity, but the court costumes provided by our costume designer (who always preferred grandeur over simplicity) were absolutely right for that context.

Mostly, we relied upon establishing a private place for the women, separated off by a screen of stylized reeds. They also sat around in informal positions, or perhaps mimed splashing each other. I seem to remember that two or three of them held up a veil as a screen for Diana, so that we might imagine her getting undressed. But as I say, there is so much sensuality in the music that who needs more? R.

WIKIPEDIA. I have just been looking at the Wikipedia article on Actaeon. It is amazingly comprehensive, and well worth a look. Apparently there are many different versions of the myth, first in Greek and then Latin. The one common element is the huntsman devoured by his hounds, but accounts differ as to the cause of his offense, and how it came about.

WIKIPEDIA. I have just been looking at the Wikipedia article on Actaeon. It is amazingly comprehensive, and well worth a look. Apparently there are many different versions of the myth, first in Greek and then Latin. The one common element is the huntsman devoured by his hounds, but accounts differ as to the cause of his offense, and how it came about.One thing common to many different versions, however, is the listing of the hounds by name. Wikipedia even gives a comparative table. The names and origins are not made up by Ovid. Steve must be right in suggesting that it belongs to a different tradition of narrative, but I found I could easily enough accept it, and indeed the whole thing was quite lively in the Charles Martin translation. Several versions, apparently, extend into a sequel in which the hounds wander the earth, filled with remorse at what they had done.

Jim, I had forgotten that Juno appeared in Charpentier's Actéon; I wonder if we somehow left her out? It seems unreasonable of her to take the credit away from Diana, and utterly unjust to seek revenge on Actaeon just because her rival Europa was his great aunt. But that is applying modern standards.

By modern standards too, Actaeon might seem a pretty useless princeling. But a life devoted to the hunt was surely par for the course, and the enormous carnage merely shows that he was good at it. No, my sympathies are pretty much with him, suffering such a fate for no apparent fault of his own. R.