Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 21-40 of 419

Kalliope wrote: "Oh, I found him in the chariot.. In an ancient Greek vase. Beautiful."

Kalliope wrote: "Oh, I found him in the chariot.. In an ancient Greek vase. Beautiful."I liked your other paintings too, especially Dumont, who manages to get just about everything into a compact and forceful design. It has occurred to me more than once that this Ovid study has given me a greater appreciation for what had previously been terra quasi-incognita: the vast amount of 17th and 18th-century paintings by artists other than the few who are truly well known. But it also increases my distaste for rococo dilution and prettifying—something you see in the Lagrenée.

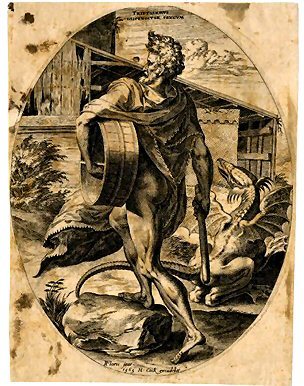

A rather similar painting, though stronger in my opinion, is this ceiling panel in the Wilanów Palace in Warsaw, by the then court painter Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter (1660—1711). It comes up in a search for Triptolemus, and it is nice to think that this might be him at lower left, wearing that very practical agricultural hat. But its title, apparently, is merely Allegory of Summer, so who knows? The British Museum, though, has a print of T. on a real farm, looking decidedly as though he means business; it is apparently after a painting by Frans Floris (1519–70).

Siemiginowski: Allegory of Summer (1686, Wilanów Palace, Warsaw)

Floris (after): Triptolemus (1565, British Museum)

Note that prominent dragon in the farmyard! Ceres lends Triptolemus her chariot pulled by dragons, as we see in another of those wonderful Liebig trading cards. But he seems to have taken them over (more frequently represented as snakes) as a distinguishing feature of his iconography. You get them peeping out from behind the bed in your Dumont picture. You get them on this Roman sarcophagus. You get them (though with vestigial wings) in the relevant Ovid engraving by our old friend Antonio Tempesta. And the serpent connection is so complete that a moth species that has learned to defend itself by making its caterpillar resemble a snake gets the name Hemeroplanes triptolemus! R.

Triptolemus in the Chariot of Ceres. Liebig trading card, c.1900?

Roman sarcophagus: The story of Triptolemus. (2nd century CE, Louvre)

Tempesta: Ceres Lends her Chariot to Triptolemus (early 17th century)

Snake-mimic caterpillar: Hemeroplanes triptolemus

The Donne poem is also the talisman for literate teenage boys, who learn about sex from Donne's string of prepositions long before they actually try them (in my case anyhow). But also note his first line: "Licence my roving hands." This is fully consensual, not rape, even though I agree with you about the more general implications of linking amatory to territorial conquest. R.

The Donne poem is also the talisman for literate teenage boys, who learn about sex from Donne's string of prepositions long before they actually try them (in my case anyhow). But also note his first line: "Licence my roving hands." This is fully consensual, not rape, even though I agree with you about the more general implications of linking amatory to territorial conquest. R.

Long before we began Book V, I posted this link to a New Yorker article by Jia Tolentino, as post #2 in the thread, to await our arrival. I imagine most people skipped right past it, eager to move ahead. But I urge everyone to give it a try. Here is the link again:

Long before we began Book V, I posted this link to a New Yorker article by Jia Tolentino, as post #2 in the thread, to await our arrival. I imagine most people skipped right past it, eager to move ahead. But I urge everyone to give it a try. Here is the link again:https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cul...

Tolentino explores her reactions to two stories from the Met, which she reads in the Rolfe Humphries translation: Arethusa/Alpheus and Daphne/Apollo. It is a very personal essay, but it ties in with aspects of current events, environmental destruction, and the big questions of sexual morality we have been grappling with since Book I. And it sings a resonant hymn of feminism:

In Against Our Will, [Susan] Brownmiller laid out a lesson that has become widely accepted only as its proof has become emotionally unbearable—that a politics of dominance over the earth, the poor, the vulnerable, is fundamentally connected to the belief that women’s bodies are rightfully subject to men. “As man conquers the world, so too he conquers the female,” Brownmiller wrote. “Down through the ages, imperial conquest, exploits of valor and expressions of love have gone hand in hand with violence to women in thought and deed.” Rape, she argued, was often presented as a heroic act, its depiction rooted in the traditions of mythology, where every god and hero seemed to be out to conquer a woman, and the ultimate result was beauty—deep water, four seasons—rather than pain.I would be interested to hear what others think of it. R.

Kalliope wrote: "The mist that Diana creates to try and protect Arethusa from Alpheus reminded me of another d..."

Kalliope wrote: "The mist that Diana creates to try and protect Arethusa from Alpheus reminded me of another d..."I like all of these, though to different degrees. The cloud adds an interesting pictorial element that makes for a tight composition without rapacious fingers on resisting flesh.

I also liked the Maes engraving best, as the real owl is more effective than a composite. Thank you for all of these. R.

Fionnuala wrote: "The advancing shadow in the Mackay painting..."

Fionnuala wrote: "The advancing shadow in the Mackay painting..."Thank you for this, Fionnuala. When I look for receptions by artists in other media, I tend to omit the step of referring them back to the original text, but this is a powerful reminder. R.

Kalliope wrote: "Thank you, Roger, for posting the paintings on Cyane. I was going to post the Mignard and Francine.. you've saved me the trouble."

Kalliope wrote: "Thank you, Roger, for posting the paintings on Cyane. I was going to post the Mignard and Francine.. you've saved me the trouble."Oh dear, I keep worrying about treading on your toes. What is the Francine? R.

MORE OPERA. It strikes me that when we come to the story of Orpheus and Euridice, we will have operatic renderings from the earliest times in operatic history to the present. Why then, given that the two stories are so similar in outline, does the Proserpina story—which you might have thought was even more dramatic—not have been equally popular with composers? The best answer I can come up with right now is that Orpheus himself was a musician. Also that, although of divine birth on both sides (Apollo and Calliope), he can be represented as something of an ordinary man contending with the gods, whereas all the characters in the story of Proserpina are on a similar plane.

MORE OPERA. It strikes me that when we come to the story of Orpheus and Euridice, we will have operatic renderings from the earliest times in operatic history to the present. Why then, given that the two stories are so similar in outline, does the Proserpina story—which you might have thought was even more dramatic—not have been equally popular with composers? The best answer I can come up with right now is that Orpheus himself was a musician. Also that, although of divine birth on both sides (Apollo and Calliope), he can be represented as something of an ordinary man contending with the gods, whereas all the characters in the story of Proserpina are on a similar plane.But still, I do keep coming up with Proserpina operas. There is Proserpine (1803) by Giovanni Paisiello (1740–1816)—best known as the composer of a Barber of Seville a generation before Rossini got to it. He wrote this in French, having been brought to Paris by Napoleon as his court composer. I have only sampled here and there. It shows more dramatic character than the Kraus opera I posted at #64, but it is still strange to hear a drama such as this portrayed in such genteel terms. Again, no videos, but a full sound recording is available. I am posting two clips. The first is the Act I finale, which I take to be the abduction scene; it strikes me as being original only in its final fade-out. Then the opening chorus of Act II, in which the nymphs (as I gather) are calling after their vanished playmate. This has a lot more vigor and is really rather enjoyable—though too much so, I would have thought, for the sadness of the occasion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixZYK...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vU0e...

Reading more, I see that Paisiello was asked to adapt a libretto from over a century before, the Proserpine (1680) by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–87). This is a longer work that Paisiello simplified, reducing the five acts to three. But the comparison is instructive. Again, there is no video but a full sound recording, and I have given links to the equivalent two clips. The first, the abduction, is the finale to Lully's Act II. It uses similar words, but is much more brief, and really captures something of the horror of the scene. And at the start of the next act, Lully also writes rather upbeat pastoral music for those searching companions, but he makes it into an echo chorus, the soft repeats of each phrase making it clear that Proserpine is no longer there to answer for herself. R.

https://youtu.be/fdnGVylRo_Q?list=PLG...

https://youtu.be/Ht0Bo_Wgy7M?list=PLG...

CYANE. I've been looking for paintings that include the nymph Cyane, who was turned into a fountain for daring to object to Pluto. There is one by Jan Soens (1547–1611) that omits the actual abduction and shows her in her pond afterwards telling her story to Ceres. For the most part, it is a perfectly ordinary landscape, though the figure of Cerberus (I think) appears rather incongrously in the bottom left corner:

CYANE. I've been looking for paintings that include the nymph Cyane, who was turned into a fountain for daring to object to Pluto. There is one by Jan Soens (1547–1611) that omits the actual abduction and shows her in her pond afterwards telling her story to Ceres. For the most part, it is a perfectly ordinary landscape, though the figure of Cerberus (I think) appears rather incongrously in the bottom left corner:

Soens: Cyane and Ceres (late C16)

Cyane does feature, however, as an attendant figure in several of the other pictures, like the Jan Brueghel in Kalliope's post #34 or the dell'Abate or Rembrandt in my #45, which have one or more assorted nymphs trying to hang on to the departing chariot; the distinguishing feature is that she should be in the water. Here is one by Nicolas Mignard (1606–68) where she is front and center, and another anonymous but striking Venetian picture where you just see her head. And there is another in the same vein as the underworld scene by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, also from Kalliope's #34, by Frans Francken the Younger (1581–1642); this has Cyane's presence clearly explained in the long title. I find the iconography of the underworld interesting, like an infernal building site; it is the same mood that Piranesi would later conjure with in his series of Prisons.

Mignard: The Rape of Proserpina (1651, private collection)

Venetian School: The Rape of Persephone (later C17)

Francken: Pluto Carrying Proserpina past the nymph Cyane, a view of the Underworld beyond (early C17, private collection)

Finally, nothing to do with Cyane at all, but I want to mention it, an illustration of the abduction story by the contemporary Scottish artist Jay Mackay. I know nothing about him, but I find the stripped-down drama of his rendering bracingly effective. R.

Mackay: Hades and Proserpina (contemporary)

My searches have just uncovered a Swedish-language opera, Proserpin (1781). It was based on a scenario by no less than the Swedish King Gustavus III, and written by the court composer Joseph Martin Kraus (1756–92), hailed as the "Swedish Mozart." Kraus and Mozart were indeed almost exact contemporaries, and listening to the music, one might well imagine Mozart. But less well-known Mozart, without much individuality of character, very little to make it unique to this story rather than some other, and certainly nothing that one might call Nordic.

My searches have just uncovered a Swedish-language opera, Proserpin (1781). It was based on a scenario by no less than the Swedish King Gustavus III, and written by the court composer Joseph Martin Kraus (1756–92), hailed as the "Swedish Mozart." Kraus and Mozart were indeed almost exact contemporaries, and listening to the music, one might well imagine Mozart. But less well-known Mozart, without much individuality of character, very little to make it unique to this story rather than some other, and certainly nothing that one might call Nordic.

Kraus: Proserpin. Scene from a 2013 production.

From what I can tell, the characters are: Proserpina and Pluto as you might expect, Ceres and Jupiter (who basically seems to have the major role), and a surprisingly significant one for Cyane, whose consensual love for Anapis (tenor) makes a secondary plot. There is a large choral presence. I can't find any video online, but there is a sound recording of all the musical numbers. The link below is cued to what I think is the actual abduction scene. R.

https://youtu.be/4QHXuHD4TTI?t=1933

Kalliope wrote: "I'm still not finished with this book and will post more this weekend, but yesterday I was struck when I received publicity from a 'cultural travel agency' I follow. They are advertising a trip to ..."

Kalliope wrote: "I'm still not finished with this book and will post more this weekend, but yesterday I was struck when I received publicity from a 'cultural travel agency' I follow. They are advertising a trip to ..."It looks well-organized and comprehensive, although I would prefer to do my cultural tourism in cooler places!

I note that this is an agency you follow, so presumably you would get this posting anyhow. But all sorts of people track our web searches, scenting profit. The word is apparently out that I look for items with classical themes, and I have been getting a noticeable amount of junk mail recently using this as a hook. I tend to trash them immediately, so don't recall specifics, but I will keep a look out. R.

Jim and Kalliope, the thing about La Calisto is that Jove wins the nymph's love in disguise as Diana, as you know. In every production I have done or been involved with, the same singer (a mezzo-soprano) sings both Diana and Jove-as-Diana. It thus becomes a huge role (since the opera also includes her romance with Endymion), but it makes the comedy quite subtle and the emotion very touching.

Jim and Kalliope, the thing about La Calisto is that Jove wins the nymph's love in disguise as Diana, as you know. In every production I have done or been involved with, the same singer (a mezzo-soprano) sings both Diana and Jove-as-Diana. It thus becomes a huge role (since the opera also includes her romance with Endymion), but it makes the comedy quite subtle and the emotion very touching.There is a recording by René Jacobs's available on DVD, however, with excerpts on YouTube, in which the bass-baritone Jove sings Jove-as-Diana himself—in falsetto, and flouncing around in a skirt. This pushes the comedy over into farce, and mutes the pathos of Calisto's confusion when Diana inexplicably rejects her, but it does even out the casting.

I don't know what solution Jane Glover adopted at Glimmerglass or what Ivor Bolton and David Alden will do in Madrid, but to me it makes a world of difference. R.

Vit wrote: "…poem by Robert Hayden."

Vit wrote: "…poem by Robert Hayden."Vit, thank you for the striking poem by Robert Hayden. I did not realize that you had posted the whole thing. It is actually formatted like a kind of short-line sonnet, which I think makes it even stronger:

Her sleeping head with its great gelid massAnother thing I did not realize until I looked it up: Hayden (1913–80) was African-American. Knowing that, it now seems full of personal and racial references: that "scathing image dire," and the deep seething anger, thirsting to destroy. Marvelous! R.

of serpents torpidly astir

burned into the mirroring shield—

a scathing image dire

as hated truth the mind accepts at last

and festers on.

I struck. The shield flashed bare.

Yet even as I lifted up the head

and started from that place

of gazing silences and terrored stone,

I thirsted to destroy.

None could have passed me then—

no garland-bearing girl, no priest

or staring boy—and lived.

Kalliope wrote: "I cannot imagine many paintings coming out of the initial battle scene, except for the inclusion of the figure of Bellona..."

Kalliope wrote: "I cannot imagine many paintings coming out of the initial battle scene, except for the inclusion of the figure of Bellona..."Thinking more about your Bellonas . . . Rembrandt rather liked dressing people up, didn't he? He must have had a rather large costume chest. But the sitters in such cases seem to be in on the joke, clearly playing the role in question.

But at least these were real live sitters, who came to his studio and did what he asked of them. Not so, surely, Marie de' Medici. I mean he lined both walls of a large gallery with her, and she can't possibly have sat for them all. I imagine he just made a portrait of her face for reference and used a paid model for the body poses. But it does seem daring to have the Queen (or future queen) pull out a breast, when the convention at least is that this is a portrait of her.

Come to think of it, I have been wondering (no, not in an erotic way) about the role of nudity in depicting classical heroes and divinities. Perseus, for instance. Why is it that the people who supposedly go into the hardest fighting are precisely the ones to leave their most delicate parts uncovered? R.

It is, Jim, isn't it?! I hope that influenced your decision too, Kalliope.

It is, Jim, isn't it?! I hope that influenced your decision too, Kalliope. Maybe I should have said that, in the opera, this is simply sung; the opening verse featuring the cornetto was added by the arranger, although the instrument is perfectly in period. One of the joys of early music is that it adapted to the forces available, so you can do these things; there is a lot of room for improvisation. R.

Kalliope wrote: "I have just received a music magazine to which I am subscribed, and on the back cover there is an add for

Kalliope wrote: "I have just received a music magazine to which I am subscribed, and on the back cover there is an add forCavalli's La Calisto.

I will consider purchasing tickets."

Oh, don't consider; call the theater now! It is a great, great opera, melodious, touching, and very funny all at the same time. And you are to have a splendid cast (both casts, actually).

I would not have associated the stage director, David Alden, with baroque opera, and there is the possibility that this may all be way over the top. But Calisto is an opera that can take it, because the basic material is so very, very good.

For a musical sampler, without prejudicing you in any way as to the staging, look at this lovely recording-session video of Calisto's first aria, sung by the lovely Nuria Rial. Watching it again makes sad to realize that the thing I will miss most in retirement is working with baroque musicians such as these! R.

https://youtu.be/H2Ks_TurCUo

There is one musical treatment of the Proserpina legend that I know of, Perséphone (1934) by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971). It is a curious hybrid, a mélodrame for speaker, solo singers, chorus, dancers, and orchestra, set to a text by André Gide (1869–1951). YouTube has a sound recording conducted by André Cluytens:

There is one musical treatment of the Proserpina legend that I know of, Perséphone (1934) by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971). It is a curious hybrid, a mélodrame for speaker, solo singers, chorus, dancers, and orchestra, set to a text by André Gide (1869–1951). YouTube has a sound recording conducted by André Cluytens:• Sound recording: https://youtu.be/rNWWdEVwVoI

However, it calls out to be staged. I saw it in the ballet made by Frederick Ashton in 1961, but there are no clips of that available. However, I found two trailers of a staging by Michael Curry designed for performance on a symphony stage. Despite the limitations, it seems to be a marvelous mixture of puppetry, dancing, and live singing—see the picture below. The two short trailers below show somewhat different excerpts:

• Oregon Symphony: https://youtu.be/0-lJZYrM590

• Seattle Symphony: https://youtu.be/IgZ-gZsCDbw

I also came upon a trailer for a staging of the work by Peter Sellars at the Lyon Opera; it does not have Curry's magic, but again it gives a different take on this most unusual work. R.

• Opéra de Lyon: https://youtu.be/DKmYArM1J4E?t=179

I'm posting one more Proserpina picture, not because I really like it, but because it is so curious. The artist is the Victorian painter Walter Crane (1845–1915); he is better known for his illustrations (an iconic set to Wagner's Ring, for example), but this is in fact an oil painting on canvas. He gets in everything from the abduction scene in Ovid's story, but while the horses are stamping and tossing their manes and the draperies are flying, all the human figures seem extraordinarily still. Perhaps this is why his called it, not the rape or abduction, but the fate of Persephone? R.

I'm posting one more Proserpina picture, not because I really like it, but because it is so curious. The artist is the Victorian painter Walter Crane (1845–1915); he is better known for his illustrations (an iconic set to Wagner's Ring, for example), but this is in fact an oil painting on canvas. He gets in everything from the abduction scene in Ovid's story, but while the horses are stamping and tossing their manes and the draperies are flying, all the human figures seem extraordinarily still. Perhaps this is why his called it, not the rape or abduction, but the fate of Persephone? R.

Crane: The Fate of Persephone (1877, private collection)

Roman Clodia wrote: "On the harmony of this book, we open with that epic battle at the wedding and close with the battle or contest of poetry between two different sets of storytellers."

Roman Clodia wrote: "On the harmony of this book, we open with that epic battle at the wedding and close with the battle or contest of poetry between two different sets of storytellers."You're right. The Martin translation (which has become my go-to, but I appear to be the only one here using it) gives titles to each book. The one here is "Contests of Arms and Song." A nice Virgil allusion! R.

One other After Ovid poem relating to Book V is "Pyreneus and the Muses" by Lawrence Joseph, who translates the feigned reverence of the lustful king described by Ovid into a very suave modern equivalent. Here is its middle section:

One other After Ovid poem relating to Book V is "Pyreneus and the Muses" by Lawrence Joseph, who translates the feigned reverence of the lustful king described by Ovid into a very suave modern equivalent. Here is its middle section:Two of his boys drove up, told us

to get in out of the rain. Took us

to the villa. Into an inner room.

From his rococo chair upholstered

with silk he arose, arms extended,

to greet us. Designer blue jeans.

T-shirt, yellow linen jacket. Face

puffy and pale. Warm, quiet gaze,

eyes, though, slightly protruding.

A manner which was obsequious

though scary. Whiskey and ice

on the table. He said: I understand

exactly what power is. Understand:

he has very deep sympathies, for children

especially. Must force himself

to execute any form of violence.

In the After Ovid collection, the Proserpina story is the subject of what may be my favorite poem in the book, by an Irish writer, Eavan Boland. Called "The Pomegranate," it is told in the voice of a mother—any mother at first. The only legend I have ever loved is / The story of a daughter lost in hell, Boland begins; …And the best thing about the legend is / I can enter it anywhere. And have. And so, as she becomes Ceres and watches her daughter make that fatal mistake, you feel that this is the poet with her own daughter, and a chain of mothers and daughters stretching down the centuries, past and present: a sadness but also a wisdom, stretching through time. Here's how it ends:

In the After Ovid collection, the Proserpina story is the subject of what may be my favorite poem in the book, by an Irish writer, Eavan Boland. Called "The Pomegranate," it is told in the voice of a mother—any mother at first. The only legend I have ever loved is / The story of a daughter lost in hell, Boland begins; …And the best thing about the legend is / I can enter it anywhere. And have. And so, as she becomes Ceres and watches her daughter make that fatal mistake, you feel that this is the poet with her own daughter, and a chain of mothers and daughters stretching down the centuries, past and present: a sadness but also a wisdom, stretching through time. Here's how it ends:She could have come home and been safe

And ended the story and all

Our heartbroken searching but she reached

Out a hand and plucked a pomegranate.

She put out her hand and pulled down

The French sound for apple and

The noise of stone and the proof

That even in the place of death,

At the heart of legend, in the midst

Of rocks full of unshed tears

Ready to be diamonds by the time

The story was told, a child can be

Hungry. I could warn her. There is still a chance.

The rain is cold. The road is flint-colored.

The suburb has cars and cable television.

The veiled stars are aboveground.

It is another world. But what else

Can a mother give her daughter but such

Beautiful rifts in time?

If I defer the grief I will diminish the gift.

The legend will be hers as well as mine.

She will enter it. As I have.

She will wake up. She will hold

The papery, flushed skin in her hand.

And to her lips. I will say nothing.