Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 81-100 of 419

MEDUSA IMAGES. As with Peter's example in #188, there are representations of Perseus story from very early times. Here are three more, focusing on the killing of Medusa. I'm not expert enough to be sure of the date of the first, which is described as Cycladic; I am interested, though, to see that Medusa is apparently portrayed as a kind of centaur, a monster in more than just her head.

MEDUSA IMAGES. As with Peter's example in #188, there are representations of Perseus story from very early times. Here are three more, focusing on the killing of Medusa. I'm not expert enough to be sure of the date of the first, which is described as Cycladic; I am interested, though, to see that Medusa is apparently portrayed as a kind of centaur, a monster in more than just her head.

Anonymous: Perseus Killing Medusa (Cycladic relief, C6 BCE? Louvre)

Anonymous: Perseus Killing Medusa (mid-C6 BCE, Palermo)

Anonymous: Perseus Killing Medusa (sarcophagus, mid-C2 BCE, Pécs, Hungary)

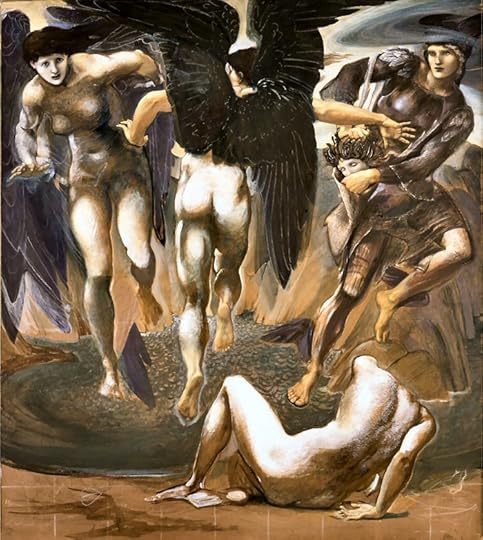

There are a few paintings, too. Baldassarre Peruzzi (1481–1536) included it in his decoration of the Villa Farnesina, in Rome. Caravaggio painted two versions of the decapitated head, as though a view of Perseus' shield. And Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) planned two versions of the slaying among the Perseus cycle he was working on at his death.

Peruzzi: Perseus Killing Medusa, Celebrated by Fame (c.1511, Rome, Villa Farnesina)

Caravaggio: Medusa (c.1597, Uffizi)

Burne-Jones: The Death of Medusa I (1882, Southhampton)

Burne-Jones: The Death of Medusa II (1882, Southhampton)

AFTER OVID. The marvelous collection

After Ovid

of Ovid-inspired poetry contains three poems relating to Book IV. I shall give brief samples of each.

AFTER OVID. The marvelous collection

After Ovid

of Ovid-inspired poetry contains three poems relating to Book IV. I shall give brief samples of each.Craig Raine departs furthest from the original in his short "Cadmus." This is the beginning and end:

the skin on his forearmsCo-editor Michael Hofmann treats "Atlas" as a kind of smart-ass Western. Here's what happens when Atlas tries to give Perseus the boot:

like the skin on egg custard

his past coming and going

a dream in the daze of dying

[ . . . ]

when they bring a mirror

to test for breath

he sees a snake

wait

no

mistake

mistake

'Son, if your daddy's notThe long "Perseus and Andromeda" by Peter Raine is more or less a straight translation of Ovid's Andromeda and Medusa sections from Book IV, together with the disturbing bloodbath that opens Book V. But his verse has an energy of its own, and the short intercalary lines produce a series of intense images ("bellowing body," "rearing and plunging," "maw of the monster," "barnacled hump-back"):

who you say he is, and your deeds

are nothing special, you in big trouble.

Now get out of here, before

I make you.' Perseus talked back,

pleaded with him, got fresh.

He grabbed him by the scruff,

lifted him clean off the ground,

carried him straight-armed

off his property like a kicking

jackrabbit and dropped him.

Red with shame and exertion,

Perseus went for his big shooter,

a museum piece, his grandmother's.

He looked the other way,

and let him have it, both barrels.

Atlas stiffened and went all big on him,

went slope, scree, treeline,

col, ridge, dome, peak.

It was really neat.

…so, swooping swiftly, Perseus bust through the

air in a steep dive,

buried his sword to the hilt in the monster's

bellowing body.

Goaded, enraged by the wound, the brute thrashed

rearing and plunging,

spinning around like the fierce wild boar when

baying hounds bait it.

Deftly avoiding the greedily snapping

maw of the monster,

playing his pinions, the hero struck its

barnacled hump-back,

thrusting his curved blade deep in its ribs and

slashing the finned tail.

PERSEUS IN MUSIC. To my surprise, the Perseus story is quite well represented in music. Here are just two examples, but there are more out there.

PERSEUS IN MUSIC. To my surprise, the Perseus story is quite well represented in music. Here are just two examples, but there are more out there.Antonio Vivaldi (1675–1741) joined with other composers to write a semi-staged serenata called Andromeda liberata in 1726. Listen to Perseus' aria "Sovente il sole" (a castrato part, here sung by a mezzo); the clip is sound-only, but the intertwining of voice and solo violin in utterly ravishing:

https://youtu.be/Y-hCC3DdRaQ

The Persée of 1682 by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–87) is a complete opera on the Perseus story. There is actually a complete DVD of the 2004 production by the Toronto company Opera Atélier; it is also available on YouTube. But I would suggest starting with the following short clip introducing Medusa, played with comic verve by bearded baritone Olivier Laquerre; it also has English titles:

Olivier Laquerre as Medusa in Lully's Persée

https://youtu.be/ZycerjSPLHQ

I didn't know either work before this. Clearly, it is an omission I must rectify! R

Peter wrote: "The story of Perseus and Andromeda surprised me...."

Peter wrote: "The story of Perseus and Andromeda surprised me...."I love your illustrated sky charts, Peter! Do you have any attribution as to artist and date? R.

The above is a tiny extract from The Earthly Paradise by William Morris (1834–96) describing the death of Medusa. Completed in 1870, it is a vast epic poem, bringing together myths from Ancient Greece and Norse sources. This particular section, "The Doom of King Acrisius," is over 2040 lines long. It tells virtually all the material from the end of Ovid's Book IV—Danaë, Perseus, Medusa, Atlas, and Andromeda—but at much greater length. It is likely this, not Ovid, that was the direct source for the paintings by Burne-Jones and Leighton shown elsewhere. R.

Finally, three Andromeda pictures from the late Nineteenth Century. Gustave Moreau (1826–98) concentrates on the princess (who doesn't look that worried), though the blood-red sunset and writhing monster do make their point.

Finally, three Andromeda pictures from the late Nineteenth Century. Gustave Moreau (1826–98) concentrates on the princess (who doesn't look that worried), though the blood-red sunset and writhing monster do make their point.

Moreau: Perseus and Andromeda (1870–80, Bristol)

This 1891 picture by Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830–96) returns to the dramatic vertical compression of Veronese or Arpino, but ups the ante by sandwiching the action between two cliffs, and having Andromeda already in the grip of the sea monster.

Leighton: Perseus and Andromeda (1891, Liverpool)

— detail of the above

Finally, this unusual painting by Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) combines two parts of the story in one: Perseus' arrival on the left (with the two looking rather suspiciously at each other!), and the fight with the monster on the right. Rather short on drama, but making a highly original composition, combining Pre-Raphaelite cool with just a hint of art nouveau.

Burne-Jones: Perseus and Andromeda (1876, Adelaide)

Compared to the Piero di Cosimo, the painting by Titian, one of the many poesie he sent to Philip II, is almost simple: just two characters plus the monster, and the town a mere shape in the distance. But how dramatic to have the hero seen from below, whirling in like a helicopter, sword and shield at the ready!

Compared to the Piero di Cosimo, the painting by Titian, one of the many poesie he sent to Philip II, is almost simple: just two characters plus the monster, and the town a mere shape in the distance. But how dramatic to have the hero seen from below, whirling in like a helicopter, sword and shield at the ready!

Titian: Perseus and Andromeda (1554–56, London, Wallace Collection)

Many other artists used a similar composition, either straight or in mirror-image. Here, for example, are versions by Paolo Veronese (1528–88), the Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari, 1568–1640), and a sketch by Rubens:

Veronese: Perseus Freeing Andromeda (1576–78, Rennes)

Cesari (Arpino) Perseus and Andromea (c.1592, Rhode Island School of Design)

Rubens: Perseus and Andromeda (1636, Rotterdam)

Rubens' other versions, however, show a later stage in the story, where the successful Perseus unties Andromeda. Here are two of them. In the Berlin version, as in the Arpino above, Perseus had ridden in on the winged horse Pegasus.

Rubens: Perseus Freeing Andromeda (c.1622, Berlin)

Rubens: Perseus Freeing Andromeda (1639–40, Prado)

Rembrandt finally, with his more intimate approach and less influenced by Italian models, paints Andromeda alone, before his rescuer has come along. We don't even see the monster, but there is no mistaking that look of fear.

Rembrandt: Andromeda (c.1630, The Hague)

AN ANDROMEDA GALLERY. With the story of the rescue of Andromeda, one of Ovid's most dramatic, we return to the A team. There are examples from Titian, Veronese, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Moreau, together with many, many other artists. But first one that is quite different, a wide-screen version containing a world of detail by the Italian artist Piero di Cosimo (c.1462–1521). Although probably painted around 1510, it is stylistically more like the previous century, not least in that the hero is shown, strip-cartoonlike, twice: arriving on his winged sandals at the upper right, and standing on the back of the sea monster in the center to kill it.

AN ANDROMEDA GALLERY. With the story of the rescue of Andromeda, one of Ovid's most dramatic, we return to the A team. There are examples from Titian, Veronese, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Moreau, together with many, many other artists. But first one that is quite different, a wide-screen version containing a world of detail by the Italian artist Piero di Cosimo (c.1462–1521). Although probably painted around 1510, it is stylistically more like the previous century, not least in that the hero is shown, strip-cartoonlike, twice: arriving on his winged sandals at the upper right, and standing on the back of the sea monster in the center to kill it.

Piero di Cosimo: Perseus Freeing Andromeda (1510–13, Florence, Uffizi)

— detail of the above

— detail of the above

As for Perseus himself, Jim posted the iconic statue by Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) at 4/109. I am repeating it here, to accompany this marvelous close-up by photographer Amanda McCracken. R.

As for Perseus himself, Jim posted the iconic statue by Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) at 4/109. I am repeating it here, to accompany this marvelous close-up by photographer Amanda McCracken. R.

Cellini: Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545–64, Florence)

— detail of the above (photo by Amanda McCracken)

Pictures of the Atlas story seem a very mixed bag. Wherever I look, the engraving below comes up, but I can find out little more about it other than that the date 1703 comes up as one of the key words. I assume the color has been added at a later date. I am more struck by the circular painting by Flemish artist Gillis Congnet (c.1535–99), the unusual watercolor by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98), or even the Liebig soup ad!

Pictures of the Atlas story seem a very mixed bag. Wherever I look, the engraving below comes up, but I can find out little more about it other than that the date 1703 comes up as one of the key words. I assume the color has been added at a later date. I am more struck by the circular painting by Flemish artist Gillis Congnet (c.1535–99), the unusual watercolor by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98), or even the Liebig soup ad!

Anonymous engraver: Perseus and Atlas (1703? color added later)

Congnet: Perseus Turning Atlas to Stone (later C16)

Burne-Jones: Perseus and Atlas (c.1878 Southhampton)

Anonymous: Perseus Turning Atlas to Stone (Liebig trading card, c.1900)

And here are two accounts of Atlas, one a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original perhaps from c.130 BCE, the other by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) showing Atlas and his daughters the Hesperides. Note that although both works correctly show Atlas supporting the heavens, these are represented by another sphere, leading to the misconception that Atlas is holding up the world.

Roman: The "Farnese Atlas" (C2 copy of Hellenistic original, Naples)

Sargent: Atlas and the Hesperides (1922–25, Boston MFA)

Incidentally, the Medusa business makes me think of a video game: you have to succeed in one adventure to pick up the things you will need in a subsequent one. In this case, the Gorgon's head becomes a talisman and a weapon in Perseus' hands.

Incidentally, the Medusa business makes me think of a video game: you have to succeed in one adventure to pick up the things you will need in a subsequent one. In this case, the Gorgon's head becomes a talisman and a weapon in Perseus' hands.

I am also perplexed about Atlas. Ovid has him transformed into a mountain by Perseus. But there are other versions which pin his punishment on Jupiter himself, as part of his conquest of the Titans. Being rooted deeper in time, I find the Jupiter story more compelling. R.

I am also perplexed about Atlas. Ovid has him transformed into a mountain by Perseus. But there are other versions which pin his punishment on Jupiter himself, as part of his conquest of the Titans. Being rooted deeper in time, I find the Jupiter story more compelling. R.

Does anyone want to comment on the telling of the Perseus story? We have, very briefly, a reference to his birth. Then an equally brief reference to Medusa. Then he is off to deal with Atlas and rescue Andromeda, and there is a further story to come I think in Book V. But…

Does anyone want to comment on the telling of the Perseus story? We have, very briefly, a reference to his birth. Then an equally brief reference to Medusa. Then he is off to deal with Atlas and rescue Andromeda, and there is a further story to come I think in Book V. But…• We only hear the Medusa story parenthetically, after the rescue of Andromeda.

• And the story of how Medusa got that way is a parenthetical appendage to that. (Another case of gross injustice to women, incidentally: Neptune rapes her, but she is the one to be punished for it!)

• And while Ovid mentions Acrisius as the father of Danaë, he does not explain that he locked his daughter up to avoid the prophecy that he himself would be killed by his son. And Perseus does kill him, though accidentally, by a misthrown discus.

Roman Clodia wrote: "I wonder, is it possible to look at the De Morgan without simultaneously thinking of Eve and the serpent?"

Roman Clodia wrote: "I wonder, is it possible to look at the De Morgan without simultaneously thinking of Eve and the serpent?"Until you mentioned it, RC, that thought hadn't entered my mind! But you have a point there: what is it with snakes and naked women? I would suggest it is precisely its metamorphic quality: that it can fascinate, insinuate, caress, embrace, and (if you care to shift the analogy) stiffen, penetrate, and poison. R.

Then there is that story of Cadmus and Harmonia changing into snakes—very odd, as somebody has already said. It has a rather beautiful ending, though. There are a good number of engravings of the scene, but almost nothing in paint. However, checking on the one canvas I could find, a late Pre-Raphaelite painting, I came upon this blog, Changing Stories: Ovid's Metamorphoses on Canvas. I have encountered it before, and others might care to know of its existence. It so happens that in this case I had selected the same three artworks as the blog author: a majolica plate by Virgiliotto Calamelli (1531–70); an engraving by Crispijn van de Passe the Elder (1589–1637), clearly based upon the same source; and a painting by the second-generation Pre-Raphaelite painter Evelyn de Morgan (1855–1919).

Then there is that story of Cadmus and Harmonia changing into snakes—very odd, as somebody has already said. It has a rather beautiful ending, though. There are a good number of engravings of the scene, but almost nothing in paint. However, checking on the one canvas I could find, a late Pre-Raphaelite painting, I came upon this blog, Changing Stories: Ovid's Metamorphoses on Canvas. I have encountered it before, and others might care to know of its existence. It so happens that in this case I had selected the same three artworks as the blog author: a majolica plate by Virgiliotto Calamelli (1531–70); an engraving by Crispijn van de Passe the Elder (1589–1637), clearly based upon the same source; and a painting by the second-generation Pre-Raphaelite painter Evelyn de Morgan (1855–1919).

Calamelli: Cadmus and Harmonia (c.1560, Faenza, Ceramic Museum)

Van de Passe: Cadmus and Harmonia Changed into Snakes (1692–07, Rijksmuseum)

De Morgan: Cadmus and Harmonia (1877, De Morgan collection)

Looking at the Evelyn de Morgan, I at first thought it was exploitative in its eroticism. But when I take in its loving detail (it is available at very large scale here) and realize its pristine purity, I have come to see it instead as a love poem in paint. De Morgan exhibited it, apparently, with the following quotation from Book IV attached. It is quite beautiful, but then so is Ovid. I don't know the translator:

With lambent tongue he kissed her patient face,

Crept in her bosom as his dwelling place

Entwined her neck, and shared the loved embrace.

Roman Clodia wrote: "I don't think I'd noticed Ino-as-Leucothea in the Odyssey - great catch, Roger!"

Roman Clodia wrote: "I don't think I'd noticed Ino-as-Leucothea in the Odyssey - great catch, Roger!"Ah, you think too highly of me (thank you, though)! Google images of the one, and the other comes up too.

Google is a wonderful implement for getting you out of the box—though you do need to follow up these leads properly for yourself. Several of the "Leucothea" images I originally found turned out to be something else entirely.

Good point about the frequency of parents killing their children, or threatening to do so. But it only reinforces my question. R.

Thinking about the Athamas story makes me very sorry for the children. Ino and Athamas at least get transformed into gods, but what about the two kids? Collateral damage? Was it just that child mortality rates were so high in those times, or were children considered even more expendable than even women? R.

Thinking about the Athamas story makes me very sorry for the children. Ino and Athamas at least get transformed into gods, but what about the two kids? Collateral damage? Was it just that child mortality rates were so high in those times, or were children considered even more expendable than even women? R.

INO/LEUCOTHEA. The scene of the maddened Athamas hurling Ino's child against a wall is a dramatic if guresome subject. Here is a superb drawing by Godfried Maes (1649–1700) and two paintings by artists I have never heard of, Arcangelo Migliarini and Gaetano Gandolfi, both painting in a somewhat archaic style for 1801:

INO/LEUCOTHEA. The scene of the maddened Athamas hurling Ino's child against a wall is a dramatic if guresome subject. Here is a superb drawing by Godfried Maes (1649–1700) and two paintings by artists I have never heard of, Arcangelo Migliarini and Gaetano Gandolfi, both painting in a somewhat archaic style for 1801:

Maes: Athamas and Ino Pursued by Tisiphone (later C17)

Migliarini: Athamas in the Power of the Furies (1801, Rome, San Luca)

Gandolfi: Athamas Killing Ino's Child (1801, private collection)

The English artist John Flaxman (1755–1826) treated the story at least twice, first as a sculpture group and later as an engraving. The latter is taken from an earlier source, the Odyssey, but deals with Ino's afterlife, after she has been transformed into the sea goddess Leucothea (the "White Goddess," as in the 1948 book by Robert Graves), and rescues Odysseus/Ulysses from shipwreck. Finally, I attach a painting of the same subject by Flaxman's contemporary Henry Fuseli (1741–1825).

Flaxman: The Fury of Athamas (1790–94, Ickworth)

Flaxman: Leucothea Preserving Ulysses (1805, London, Tate)

Fuseli: The Shipwreck of Odysseus (1803, private collection)

Back to a little earlier in the story, Juno's visit to the underworld, in this ghoulish panorama by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1588–1625). He is the master of profuse and curious detail whom we have seen before collaborating with Rubens in posts 1/55 and 4/103.

Back to a little earlier in the story, Juno's visit to the underworld, in this ghoulish panorama by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1588–1625). He is the master of profuse and curious detail whom we have seen before collaborating with Rubens in posts 1/55 and 4/103.

Brueghel, Jan: Juno in Hades (1598, Dresden)

— detail of the above

And an engraving from Dante's Inferno by Gustave Doré (1832–83), showing Virgil pointing out the Erynies (Furies), one of whom is Tisiphone whom Juno singles out for her task. Fearsome women!

Doré: Virgil Pointing Out the Erinyes to Dante (engraving, 1890)

— detail of the above