Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 121-140 of 419

Oh, I'm sure you're right, Peter, though I didn't realize that the Rusalka story was so old. But she, like The Little Mermaid, enters the human world because she aspires to human life, doesn't she? Tragic outcome, perhaps, but neither predatory nor malevolent.

Oh, I'm sure you're right, Peter, though I didn't realize that the Rusalka story was so old. But she, like The Little Mermaid, enters the human world because she aspires to human life, doesn't she? Tragic outcome, perhaps, but neither predatory nor malevolent.So these belief systems personify various aspects of the real world. What is interesting is that the characteristics we give these personifications come to embody some of our worst behaviors and most deep-seated fears. The idea, in this case, of a predatory and ultimately castrating female. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "I agree, Roger, Ovidian material in inexhaustible. I've just today accepted an invitation to give a paper at a seminar on Ovid and Love."

Roman Clodia wrote: "I agree, Roger, Ovidian material in inexhaustible. I've just today accepted an invitation to give a paper at a seminar on Ovid and Love."Kudos to you! But you've written on Ovid often before, haven't you? Meanwhile, on another level entirely, all this has been preparation for my own course on Ovid's legacy, which has now grown from my original proposal of a half semester (6 weeks) to the full deal of 24 hours. And even then…! R.

Thank you, Fionnuala. The more I look into Ovid in art, the more I realize that Kalliope and I and others here are only a few of many who have undertaken the same inquiry; there are quite a few blogs out there. Yet the more I do it, the more I find my search asking questions that are new to me at least, whether about Ovid, or narrative, or the role of art, or the continual balancing act between persistent myth and individual inspiration. R.

Thank you, Fionnuala. The more I look into Ovid in art, the more I realize that Kalliope and I and others here are only a few of many who have undertaken the same inquiry; there are quite a few blogs out there. Yet the more I do it, the more I find my search asking questions that are new to me at least, whether about Ovid, or narrative, or the role of art, or the continual balancing act between persistent myth and individual inspiration. R.

SALMACIS (#4/4). I'd like to round this up by a group of artworks in which, as in the third Albani picture above, the two figures are actually in contact. The first, by Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752), has an interesting history in that it was looted by the Nazis for Hitler's collection at Berchtesgarten, and restored after the war. The statue in Warsaw is one of the few sculptural renditions I can find that actually tells the story. Looking at the painting by Giovanni Carnovali (1804–1873), an artist I did not know at all, I might almost have thought Renoir; it is one of the most sensuous of the lot, and almost lesbian in its gender ambiguity. Finally, a painting by the Carl Bertling (1835–1918), rethinking the story in terms of German romanticism.

SALMACIS (#4/4). I'd like to round this up by a group of artworks in which, as in the third Albani picture above, the two figures are actually in contact. The first, by Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752), has an interesting history in that it was looted by the Nazis for Hitler's collection at Berchtesgarten, and restored after the war. The statue in Warsaw is one of the few sculptural renditions I can find that actually tells the story. Looking at the painting by Giovanni Carnovali (1804–1873), an artist I did not know at all, I might almost have thought Renoir; it is one of the most sensuous of the lot, and almost lesbian in its gender ambiguity. Finally, a painting by the Carl Bertling (1835–1918), rethinking the story in terms of German romanticism.

De Troy: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1729, private collection)

Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (C18 statue in Lazienki Park, Warsaw)

Carnovali: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1856, private collection)

Bertling: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1892, private collection)

I include the Bertling to pose a question. Salmacis is generally identified as a Naiad, or water nymph. As such, she is a curious Latin forerunner of all those Northern European myths of female spirits who emerge from the waters to prey on passing men. Lorelei, for instance, or Undine, the subject of Adam Mickiewicz's poem Switezianka, supposedly the inspiration of Chopin's third Ballade. Is there a direct transalpine link between the two myths, or did they arise independently out of the same Jungian well? R.

SALMACIS (#3/4). One name that crops us a lot with Salmacis paintings is Francesco Albani (1578–1660). Here are three, between them showing various stages of Ovid's story. In the wide panel in the Louvre, she watches from a considerable distance; in the drawing, they are much closer; and the third painting shows their actual encounter.

SALMACIS (#3/4). One name that crops us a lot with Salmacis paintings is Francesco Albani (1578–1660). Here are three, between them showing various stages of Ovid's story. In the wide panel in the Louvre, she watches from a considerable distance; in the drawing, they are much closer; and the third painting shows their actual encounter.

Albani: Hermaphroditus and Salmacis (1630–40, Louvre)

Albani: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (drawing)

Albani: Salmacis Rejected by Hermaphroditus (Turin)

With all three, but the drawing especially, I am struck by how young Albani makes the figures; these are children, virtually. One more Italian painting from the same period: this one by Lodovico Carracci keeps them apart still, but makes the youth of the boy especially clear:

Carracci: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (early C17, private collection)

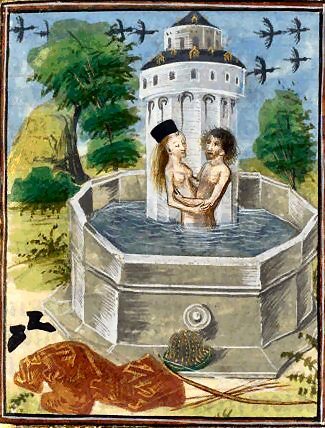

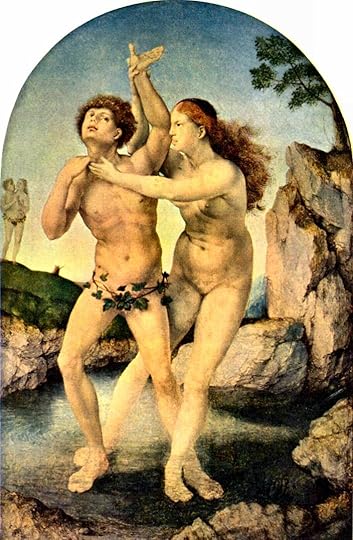

SALMACIS (#2/4). A large number of the Ovid paintings we have been looking at come from the later Renaissance or especially the Baroque, so it is interesting to see earlier examples, such as these three. The first two are illuminated manuscripts from the 15th century; the third is a painting by Jan Gossaert (aka Mabuse), a Netherlandish painter of about a century later. It is interesting that neither of the manuscripts give much indication of the nymph's aggression; Gossaert does a little, but this is an aspect that will appeal more to baroque artists, looking for drama in everything. It is also interesting that the second manuscript shows the amalgamation of the two bodies into one—as does the Gossaert, if you look carefully on the left bank. R.

SALMACIS (#2/4). A large number of the Ovid paintings we have been looking at come from the later Renaissance or especially the Baroque, so it is interesting to see earlier examples, such as these three. The first two are illuminated manuscripts from the 15th century; the third is a painting by Jan Gossaert (aka Mabuse), a Netherlandish painter of about a century later. It is interesting that neither of the manuscripts give much indication of the nymph's aggression; Gossaert does a little, but this is an aspect that will appeal more to baroque artists, looking for drama in everything. It is also interesting that the second manuscript shows the amalgamation of the two bodies into one—as does the Gossaert, if you look carefully on the left bank. R.

Master of the Cité des Dames: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (c.1414, British Museum)

Anonymous illuimnator: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (15th century Flemish)

Gossaert: The Metamorphosis of Hermaphrodite and Salmacis (c.1517, Rotterdam)

SALMACIS (#1 of 4). By far my favorite depiction of the story of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus is this one by Bartholomeus Spranger (1546–1611), a Netherlandish painter who spent ten years in Rome then became court painter to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Goltzius, apparently, made many engravings of his work.

SALMACIS (#1 of 4). By far my favorite depiction of the story of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus is this one by Bartholomeus Spranger (1546–1611), a Netherlandish painter who spent ten years in Rome then became court painter to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Goltzius, apparently, made many engravings of his work.

Spranger: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (c.1585, Vienna)

I had barely heard of the artist, let alone this painting, until I came upon a color plate of it in Paul Barolsky's Ovid and the Metamorphoses of Modern Art from Botticelli to Picasso. Barolsky points out that this is a picture of a voyeur: Salmacis watching Hermaphroditus from concealment as he gets undressed. But what is special about this picture is that, by placing Salmacis, so large and half-undressed herself, between us and the object of her desire, Spranger is making a voyeur of the viewer also, watching the nymph unseen with (if we are male) just as much desire as she feels for Hermaphroditus. Among many other observations, Barolsky also points out the beautiful rhyme between Salmacis taking off her sandal and part of her undressing, and Hermaphriditus doing the same on the other side of the water, even though in a different pose.

Thinking about this picture also makes me realize something that paintings do much more easily than narrative: they freeze time. You could imagine lining up a number of pictures, like in a strip cartoon, to form a story-board of an action. But among them, there will be one or two that are special because they show the potential for something happening, rather than the action or its result. Keats wrote a whole poem, "Ode on a Grecian Urn," on the magic of the uncompleted moment: "Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair." A storyteller cannot so easily halt time in this way; a painter can, and in this respect, Spranger's Salmacis is a marvel. R.

Historygirl wrote: "Sorry I am a bit behind in posting ..."

Historygirl wrote: "Sorry I am a bit behind in posting ..."Histgorygirl, you cannot be behind; there is no timekeeper here, no taskmaster's whip! I do agree with you about Bacchus, though; I find myself not liking at all as Ovid presents him. R.

My gosh, Jim, I hope so too! I think my last visit was in 1970, almost half a century ago. I'm not on to the Perseus stories yet, apart from that first quick scan to make my index, but I am very much aware that he is probably the most significant mythical hero that I know next to nothing about. Right now, I'm still on Salmacis. R.

My gosh, Jim, I hope so too! I think my last visit was in 1970, almost half a century ago. I'm not on to the Perseus stories yet, apart from that first quick scan to make my index, but I am very much aware that he is probably the most significant mythical hero that I know next to nothing about. Right now, I'm still on Salmacis. R.p.s. Would you tell me if you can get hold of anything more substantial from that P&T opera, other than the clips I posted?

A similar confusion hangs over the fate of Clytie, who is turned into a heliotrope, always facing the sun. From photographs I have seen, however, I would have thought that the flowers were too small for this to be much more than a myth. So she is more often represented as the sunflower, whose blooms do appear to turn.

A similar confusion hangs over the fate of Clytie, who is turned into a heliotrope, always facing the sun. From photographs I have seen, however, I would have thought that the flowers were too small for this to be much more than a myth. So she is more often represented as the sunflower, whose blooms do appear to turn.Such is the case in this 18th-century tapestry based on a design by François Boucher. I don't entirely understand it, though, because it appears that Clytie has got her wish and is indeed up with Phoebus in the heavens. Unless, of course, this position of looking adoringly up from the level of his knees is as far as she will ever get.

Boucher (after): Clytie and Apollo (later C18)

The beautiful painting below by Nicolas-René Jollain is easier to understand as an expression of unrequited yearning. Below that is the last painting by Frederick, Lord Leighton, left unfinished at his death in 1896. There is almost nothing mythological about it, no flower, no visible sun, simply this strong image of a woman devoting herself entirely to the light.

Jollain: Clytie Following the Progress of Apollo (later C18)

Leighton: Clytie (1896, London, Leighton House)

And finally, two sculpture busts, both showing the bust of a young woman emerging from the center of a sunflower. That is the only aspect identifying the anonymous marble from early in the 19th century, but the pose of the bust by George Frederic Watts is quite specific in the way her head is twisted round to follow her god. R.

Anonymous: Clytie (early C19)

Watts: Clytie (1868, London, V&A)

There are a number of illustrations of the story of the Sun/Apollo and Leucothoë, mainly in prints: a late 18th-century illustration of him arriving in disguise as her mother; an engraving by Wilhelm Baur that is striking as an image of morning sunlight streaming into a luxurious interior; another by Antonio Tempesta that seems unusually explicit; and finally a painting by the Frenchman Antoine Boizot that might almost be an apotheosis, but is clearly still in the interior setting.

There are a number of illustrations of the story of the Sun/Apollo and Leucothoë, mainly in prints: a late 18th-century illustration of him arriving in disguise as her mother; an engraving by Wilhelm Baur that is striking as an image of morning sunlight streaming into a luxurious interior; another by Antonio Tempesta that seems unusually explicit; and finally a painting by the Frenchman Antoine Boizot that might almost be an apotheosis, but is clearly still in the interior setting.

Anonymous: Apollo and Leucothoë (late C18)

Baur: Apollo and Leucothoë (1639)

Tempesta: Apollo and Leucothoë (mid C17)

Boizot: Apollo Caressing The Nymph Leucothea (1737, Tours)

I can find nothing to illustrate Leucothoë's later fate of being buried alive by her father, then turned into the shrub that bears her name. I am perplexed here, though. I have usually seen it that she is turned into frankincense, yet that tree, Boswellia sacra, appears to be quite different from Leucothoe axillaris and similar species.

There might have been a Leucothoë opera, but wasn't. Wikipedia notes "Leucothoé is a 1756 dramatic poem by the Irish playwright Isaac Bickerstaff. It was Bickerstaff's first published work. Leucothoé was originally intended to be a pastoral opera but Bickerstaff was unable to secure a composer to set it to music."

There might have been a Leucothoë opera, but wasn't. Wikipedia notes "Leucothoé is a 1756 dramatic poem by the Irish playwright Isaac Bickerstaff. It was Bickerstaff's first published work. Leucothoé was originally intended to be a pastoral opera but Bickerstaff was unable to secure a composer to set it to music."So much for that! R.

Looking through the Paul Barolsky just now, I came upon another painting of the story of Mercury, Aglauros, and Herse that I should have known (because it's in Cambridge, and I got my art history degree from there), but had forgotten:

Looking through the Paul Barolsky just now, I came upon another painting of the story of Mercury, Aglauros, and Herse that I should have known (because it's in Cambridge, and I got my art history degree from there), but had forgotten:

Veronese: Mercury, Aglauros, and Herse (1576–84, Cambridge UK)

Veronese chooses the moment just before the touch of Mercury's wand turns the jealous Aglauros to stone. He has perfectly caught Ovid's description of her crouching at the door trying to prevent the entrance of the god:

At length before the door her self she cast;The Fitzwilliam Museum has a close explanation of the picture, with tiny thumbnails, each of which can be opened up to show a telling detail; it is worth a look:

And, sitting on the ground with sullen pride,

A passage to the love-sick God deny'd.

The God caress'd, and for admission pray'd,

And sooth'd in softest words th' envenom'd maid.

In vain he sooth'd: "Begone!" the maid replies,

"Or here I keep my seat, and never rise."

"Then keep thy seat for ever," cries the God,

And touch'd the door, wide op'ning to his rod.

Fain would she rise, and stop him, but she found

Her trunk too heavy to forsake the ground…

https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/phar...

Elena, your link didn't quite work, but it was easy enough to get to the right one:

Elena, your link didn't quite work, but it was easy enough to get to the right one:https://www.westedgeopera.org/orfeo-e...

More than anything, I was struck by the photograph they took to illustrate the production: just a figure in a graveyard. Easy enough to do and inexpensive, but somebody* showed real imagination; it sums up the opera perfectly.

Photo: Corey Weaver

I don't know why they emphasize the all-female cast; there are only three characters, and that is pretty much the norm. They would still have to have men in the chorus, though.

Anyway, there are a lot of Orpheus operas. I look forward to posting a bunch of links when we come to Book X. R.

*That "somebody," I now see, is Corey Weaver, one of the leading opera photographers today. I have also been fortunate enough to have him do one or two shows of mine.

Lyn wrote: "I’ve just found an interesting article on Ted Hughes’ Tales from Ovid…"

Lyn wrote: "I’ve just found an interesting article on Ted Hughes’ Tales from Ovid…"As you may see, I am indexing many of Hughes' poems as derivative works rather than straight translations. Nothing pejorative about that. As a straight translator, as he is in many of the episodes, he is good but not always the best. When he riffs on the Ovid with ideas of his own, however, he is riveting.

I'll look at that article. R.

MARS AND VENUS AS ADULTERERS. Of course, the point of Ovid's story—and Homer's before him—is that the affair of Mars and Venus was an adulterous one, and they were caught in flagrante delicto by Venus' husband, Vulcan. The truly Ovidian/Homeric depictions, therefore, are those which do not simply show a state of affairs but tell a story. They are fewer in number, but still plenty to choose from.

MARS AND VENUS AS ADULTERERS. Of course, the point of Ovid's story—and Homer's before him—is that the affair of Mars and Venus was an adulterous one, and they were caught in flagrante delicto by Venus' husband, Vulcan. The truly Ovidian/Homeric depictions, therefore, are those which do not simply show a state of affairs but tell a story. They are fewer in number, but still plenty to choose from.Working into it, however, let me start with two that merely hint at what is to happen. In this relief by the neoclassical Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, the affair has not even begun. But Venus, as we can see, is more interested in the arrow that Cupid is pointing to in Mars' hand than the ones she is tempering for her husband!

Thorvaldsen: Venus, Mars and Cupid in the Smithy of Vulcan (c.1810, Nysø, Thorvaldsen Museum)

Perhaps the next picture, by Palma il Vecchio, really belongs in the non-specific category. But I include it because it is the earliest in the group, because it so beautifully captures the Venetian landscape of Giovanni Bellini, and because that gentleman looking down from the clouds at top right just might be the Sun, who in Ovid gives the game away.

Palma: Mars, Venus, and Cupid (c.1520, NG of Wales)

Such subects appealed to Venetians. We have had Titian and Veronese in a previous post, but there remains Tintoretto. His painting of "Vulcan, Venus, and Mars" seems to have only two actors, although there is also a Cupid asleep in a cot and a little dog on the floor. So where is Mars? I read in a blog that we can see him in the shield/mirror at the back, but I don't think so. If you look carefully, however, you can see his head poking out from under the table; the great warrior is hiding!

Tintoretto: Venus, Mars, and Vulcan (c.1551, Munich AP)

— enhanced detail of the above,

Here is a strong composition by an artist I had never heard of, Alessandro Varotari a.k.a. Il Padovanino. Vulcan is in the act of throwing the net over Venus and Mars, who, although looking far too fresh for what they are presumably doing, react with dramatic surprise.

Varotari: Venus and Mars Surprised by Vulcan (c.1631, private)

The story in Ovid and Homer does not end with Vulcan's entry, but takes the ridicule of the gods as its punchline. It seems to have been a favorite approach for Northern artists. Here are three of them: a dramatic pose from Maarten van Heemskerck, although the adulterous couple seem strangely weak; from Frans Floris, another tryst-in-a-landscape like Palma Vecchio's, only with the gods looking on; and the full picture by Adrien Wtewael whose lovers I showed in close-up earlier—I'm afraid the central action is woefully diluted by all that flesh.

Van Heemskerck: Vulcan, Venus and Mars (1540, Vienna)

Floris: Venus and Mars (mid C16; Antwerp, Rubenshuis)

Wtewael: Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan (1604–08, Getty)

Some Italian baroque painters used the subject too. Here is a version by Luca Giordano. It may be one of the most successful of the lot for its tonal balance and chiaoscuro.

Giordano: Mars and Venus Caught by Vulcan (1670s, Vienna)

But I have a sneaking fondness for this one by the German master Johann Heiss (1640–1704). He really goes to town on the idea of bringing in the entire Olympian pantheon (serve them right for having their tryst in such a large room!), but holds it all together by a beautiful control of light and shade.

Heiss: Vulcan Surprising Venus and Mars in Bed before an Assembly of the Gods (1679, private)

— detail of the above.

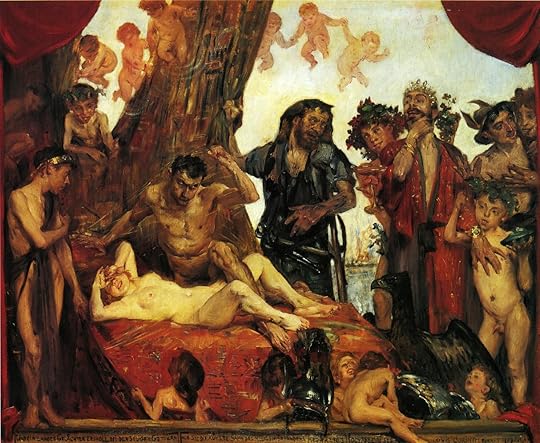

And finally the 1909 version of the subject by another German, Lovis Corinth, that I posted already in post #69, but will repeat here as a reminder. It now seems crude to me beside the wit and refinement of some of the others we have seen.

Corinth: Homeric Laughter (1909, Munich)

VENUS + MARS = PEACE. With this, we are now completely off-topic, since Ovid describes a scandal and there is nothing scurrilous about the allegory of Love taming War to produce Peace. But it deserves at least a little footnote, as there are some interesting paintings to have made this point. In the first half of the 17th century, both Rubens and Poussin attempted the theme. Rubens placed the loving couple at one side of a vast still life of discarded instruments of war; for these, he called upon detail specialist Jan Brueghel the Elder, collaborating as they did in their Pan and Syrinx (post 1/55). Poussin takes an entirely different approach, showing the rightness of the peaceful union through the Arcadian landscape, the presence of other attendant deities, and the Cupids playing with the no-longer-needed arrows.

VENUS + MARS = PEACE. With this, we are now completely off-topic, since Ovid describes a scandal and there is nothing scurrilous about the allegory of Love taming War to produce Peace. But it deserves at least a little footnote, as there are some interesting paintings to have made this point. In the first half of the 17th century, both Rubens and Poussin attempted the theme. Rubens placed the loving couple at one side of a vast still life of discarded instruments of war; for these, he called upon detail specialist Jan Brueghel the Elder, collaborating as they did in their Pan and Syrinx (post 1/55). Poussin takes an entirely different approach, showing the rightness of the peaceful union through the Arcadian landscape, the presence of other attendant deities, and the Cupids playing with the no-longer-needed arrows.

Rubens and Jan Brueghel I: The Return from War: Mars Disarmed by Venus (1610–12, Getty)

Poussin: Mars and Venus (c.1630, Boston MFA)

Of course these high philosophical ideals appealed to the French of the neo-classical period. Here are three examples, two are which are intimate in context with lingering traces of rococo, and the third grandiose. Louis Jean François Lagrenée indeed has a bed scene, but his title focuses on the foreground, where two of Venus's doves make a nest in Mars's discarded helmet. The very same metaphor is used by Joseph-Marie Vien, but now with Venus leading Mars out of bed to see what her doves have done. Contrast Jacques-Louis David choosing the subject as his last work, in a grand allegorical statement that harks back to the great political manifestos he painted for Napoleon, and that still hang in the Louvre.

Lagrenée: Mars and Venus, Allegory of Peace (1770, Getty)

Vien: Venus Showing Mars her Doves Making a Nest in his Helmet (1768, Hermitage)

David: Mars Disarmed by Venus (1822, Brussels)

MARS AND VENUS, AS MAN AND WOMAN. Just because an artwork depicts Mars and Venus does not necessarily make it Ovidian. In fact, there are many more paintings out there that just put the two of them together than those that tell a story. I mean, what a perfect excuse to paint a naked woman and a super-manly man! This fresco in Pompeii, for example, simply puts them together—although there is a hint that more may develop from their meeting:

MARS AND VENUS, AS MAN AND WOMAN. Just because an artwork depicts Mars and Venus does not necessarily make it Ovidian. In fact, there are many more paintings out there that just put the two of them together than those that tell a story. I mean, what a perfect excuse to paint a naked woman and a super-manly man! This fresco in Pompeii, for example, simply puts them together—although there is a hint that more may develop from their meeting:

Roman (Pompeii): Mars and Venus (mid-C1, Pompeii, House of Mars and Venus)

That hint goes even further in the painting by Titian, who is as sensuous as always in mythological subjects. This looks as though sex has already happened, and Mars is giving Venus a farewell kiss. But note, there is no hint of adultery:

Titian: Mars and Venus (c.1530, Vienna)

Coming upon the picture below on the web, I at first took it for another Titian. only going yet farther in its explicitness. I later discovered that it is a detail from a painting of the lovers surprised by Vulcan, thus belonging in the next post but one (q.v.). When you see it in full, however, the effect will be quite different.

Wtewael: Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, detail. (1604–08, Getty)

Playing down the sexuality somewhat are these two paintings by Veronese. The first, in the National Galleries of Scotland, despite its luxuriant trappings, is a rather charming domestic scene. The slightly older one in the Metropolitan, however, is grander in conception, with a war horse in the background and a Cupid taking the conqueror's sword. Here, I think, the simple roles of man and woman take second place to God of War and Goddess of Love, so that the painting has a political point quite as much as a sexual one; I will pursue it in the next post.

Veronese: Mars, Venus, and Cupid (c.1580, NG of Scotland)

Veronese: Mars and Venus United by Love (1570s, NY Met)

Vit wrote: "Roger wrote: "Vit wrote: "Andromeda is rescued from the Sea Monster in this way:

Vit wrote: "Roger wrote: "Vit wrote: "Andromeda is rescued from the Sea Monster in this way:“A ridgy hold, he, thither flying, gain’d,

And with one hand his bending weight sustain’d;

With th’ other, vig’rous ..."

Thanks, Vit. I have often used that too, but the language of this section seemed more vigorous than most. R.

Vit wrote: "Andromeda is rescued from the Sea Monster in this way:

Vit wrote: "Andromeda is rescued from the Sea Monster in this way:“A ridgy hold, he, thither flying, gain’d,

And with one hand his bending weight sustain’d;

With th’ other, vig’rous blows he dealt around,

And..."

Whose translation are you quoting, Vit? And thanks for the Barth, an author I have never read. R.