Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 141-160 of 419

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roger wrote: "One of the "learned poets of antiquity" who comes to mind is of course Catullus. But I think Beccadelli goes even further, and is even more pointedly ad hominem. I suspect, however, t..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roger wrote: "One of the "learned poets of antiquity" who comes to mind is of course Catullus. But I think Beccadelli goes even further, and is even more pointedly ad hominem. I suspect, however, t..."RC, was Beccadelli writing in Latin? I had assumed Italian. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "On Renaissance versions of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus we have Beaumont's 1602 English Salmacis and Hermaphroditus and the earlier bawdy Hermaphroditus of Antonio Beccadelli."

Roman Clodia wrote: "On Renaissance versions of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus we have Beaumont's 1602 English Salmacis and Hermaphroditus and the earlier bawdy Hermaphroditus of Antonio Beccadelli."Two more for my catalogue, Clodia; thanks! And thanks for your close analysis of the Salmacis story as told by Ovid.

I couldn't get your Google link to the Beccadelli to work, but I did find a preview of the no-holds-barred translation by Eugene O'Connor. Alas, though, I could not find a single poem tame enough to quote in mixed company (hey, what a sexist phrase that is!). But here, as a mild sample, are eight lines from the dedication to Cosimo de' Medici:

This work of mine could tease loud laughterOne of the "learned poets of antiquity" who comes to mind is of course Catullus. But I think Beccadelli goes even further, and is even more pointedly ad hominem. I suspect, however, that the title is only there as an indication that these are equal-opportunity obscenities, skewering male and female alike, with a special niche for pederasts. It appears to have little connection with Ovid.

even from the mirthless; it could stir

the frozen member of Hippolytus.

In this (to my defense) I follow in the steps

of the learned poets of antiquity,

who (it's well known) wrote lascivious verses,

and—even if their pages were replete with obscenities,

were famed as well for living upright lives.

Have you read the Beaumont all through? I skimmed it only, I'm afraid. He does indeed tell Ovid's story, but he encases it in references to just about every other god, demigod, and mythical figure on his way there. One thing that interested me was that Salmacis was not sexually awakened until Bacchus seduces her—or almost, for Phoebus intervenes:

He kept her from the sweets of Bacchus bed,When Beaumont comes to her actual encounter with Hermaphroditus, however, he is splendidly direct in the language he puts into her mouth (though once more with reference to several other stories):

And 'gainst her will he sau'd her maiden-head.

"Wert thou a mayd, and I a man, Ile show thee,I love "a lower, yet a higher blisse." And I can just see the killing flash when "her eye-lids wide she did display"! Too bad the boy was already on the run! R.

With what a manly boldnesse I could woo thee,

Fayrer then loues Queene, thus I would begin,

Might not my ouer-boldnesse be a sinne,

I would intreat this fauor, if I could,

Thy rosiat cheeke a little to behold:

Then would I beg a touch, and then a kisse,

And then a lower, yet a higher blisse:

Then would I aske what Ioue and Læda did,

When like a Swan the craftie god was hid?

What came he for? why did he there abide?

Surely I thinke hee did not come to chide:

He came to see her face, to talke, and chat,

To touch, to kisse: came he for nought but that?

Yea, something else: what was it he would haue?

That which all men of maydens ought to craue."

This sayd, her eye-lids wide she did display:

But in this space the boy was runne away:

The wanton speeches of the louely lasse

Forc't him for shame to hide him in the grasse.

Returning to what I was saying in post #68 about Bacchantes being either erotic or wild, but seldom both, I have found an exception to that rule. By the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre, who painted the picture of Pentheus fleeing the Bacchantes that Kalliope posted in 3/150, it represents a celebration that is both orgiastic and apparently excessive. Note the tiny figure on the pedestal, presumably of Bacchus, who set this whole thing off. R

Returning to what I was saying in post #68 about Bacchantes being either erotic or wild, but seldom both, I have found an exception to that rule. By the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre, who painted the picture of Pentheus fleeing the Bacchantes that Kalliope posted in 3/150, it represents a celebration that is both orgiastic and apparently excessive. Note the tiny figure on the pedestal, presumably of Bacchus, who set this whole thing off. R

Gleyre: Dance of the Bacchantes (1849, Lausanne)

EUROPA OPERAS? Slim pickings here, I'm afraid, or rather two near misses.

EUROPA OPERAS? Slim pickings here, I'm afraid, or rather two near misses.1. L'Europa, "opera prologue in one act" by Alessandro Melani (1667). I came upon this only through this advertisment for a production at Potsdam last summer. The describe it as a Barockoper mit göttlichem Brautraub, or "Baroque Opera with Godly Bride-Theft," so at least it deals with the central action. But it appears to be simple, with only the two main characters and a narrator, and it is short. I can find out nothing more about it, and precious little on the composer.

2. Europa riconosciuta, ("Europa Revealed") by Antonio Salieri (1776). This is a significant work in operatic history, as it was the inagural production at La Scala, and revived when the theatre re-opened in 2004 after a three-year closure. However, beyond the fact that two of its characters are called Europa (that Europa) and Semele (but not that Semele), its plot has nothing to do with Ovid. The 2004 revival is on YouTube in sound only, and there are a few quite good clips, some with English titles. It is clearly a big serious opera, with long arias of daunting virtuosity, much as you find, say, in Mozart's Idomeneo or La clemenza di Tito.

• Sound recording (complete)

• Aria for Europa

• Aria for Semele

• Scene for Semele and Isseo

• Ballet

Elena wrote: "The Berkeley Rep will be performing Metamorphoses by Mary Zimmerman January 24 to March 10 , 2019."

Elena wrote: "The Berkeley Rep will be performing Metamorphoses by Mary Zimmerman January 24 to March 10 , 2019."I would like to have seen that, preferably in her own original production. R.

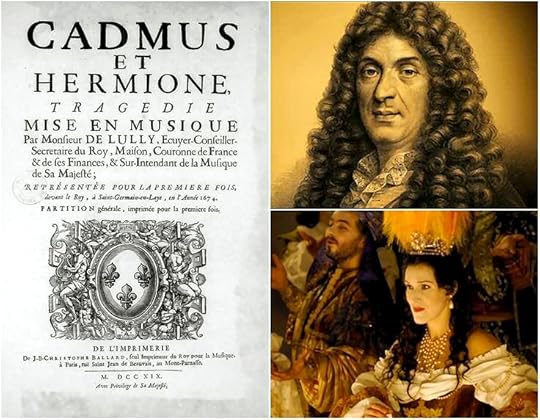

There is an opera on the Cadmus story. Cadmus et Hermione. This was Jean-Baptiste Lully's the first tragédie en musique (the word simply means grand opera; it ends happily); it was written in 1673 to a text based loosely on Ovid. And I do mean loosely. While the episode of killing the dragon and sowing its teeth is included, most of the text concerns the mutual love of the hero and the beautiful Hermione (aka Harmonia); they are prevented from marrying until the very end because of the rivalry of their respective patrons, Pallas and Juno.

The various clips on YouTube all derive from a 2008 production at the Opéra Comique. It is a loving attempt to recreate baroque choreography, costumes, scenery, stage machinery, and (unfortunately) lighting. Most of the shorter clips are better, but the one showing the entire opera, with double titles in French and English, is sadly degraded. The link below takes you to Act Three, which contains the dragon episode. It begins, however, in comedy (unusually for Lully) featuring Cadmus' vainglorious servant Arcas—clearly cut from the same cloth as Mozart would later use for his Papageno!

https://youtu.be/6wC5wZYy85M?t=4592

I realize that not only is there an opera on the Cadmus story, but that it also makes reference to Apollo slaying Python. Cadmus et Hermione (aka Harmonia) was Jean-Baptiste Lully's the first tragédie en musique (the word simply means grand opera; it ends happily); it was written in 1673 to a text based loosely on Ovid. The prologue, which is separate from the main story, tells of Apollo vanquishing Python—Apollo in this case being a clear reference to Louis XIV, the Sun King. In this production from the Opéra Comique, you see a splendidly melodramatic Envy come in at 5:52, accompanied by aerial demons and a quite charming snake. Apollo does not appear in person to restore order; the sun merely breaks through the clouds (and even that is hardly shown). But he does make a magnificent entrance from the heavens at 12:23, now clearly the King, to accept everybody's thanks.

https://youtu.be/90DHbJvhZIo

Yes they are. If you are interested in the whole cycle, look at the link that Peter posted; it gives much larger and more radiant photos than I could reproduce, with many details. R.

Yes they are. If you are interested in the whole cycle, look at the link that Peter posted; it gives much larger and more radiant photos than I could reproduce, with many details. R.Der Metamorphosen Zyklus der Ovidgallerie

Jim wrote: "Which reminds me why "well-bred" young ladies of the Victorian era were discouraged from reading Swinburne ...."

Jim wrote: "Which reminds me why "well-bred" young ladies of the Victorian era were discouraged from reading Swinburne ...."And well-bred boys of the postwar era too. It comes back to me that the Ovid we were given at age 12 was almost certainly not a complete book, but tales otherwise unaltered, but selected to avoid the hotter episodes. Hence the one I remember best (largely for its lack of appeal to boys of our age) was Philemon and Baucis—safe as houses!. I'm sure we read others too; we were expected to get through the stuff at an alarming rate. Had we been selecting from Book IV, Pyramus and Thisbe would have been fine, Mars and Venus iffy, and Hermaphroditus totally taboo! R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "... no time to chat now, but is Salmacis the closest we come to a female rapist?"

Roman Clodia wrote: "... no time to chat now, but is Salmacis the closest we come to a female rapist?"Well, there's Dercetis too, the first of the Minyades' not-told stories, perhaps mentioned as a preparation for Salmacis (or as Nora would say, prolepsis). R.

And Swinburne's dateline, at the Louvre, made we wonder what inspired him there. And of course, the Sleeping Hermaphroditus ! For some reason, in all my dozens of visits, I have never stopped to look at it. So I shall give the opening of the Wikipedia article:

And Swinburne's dateline, at the Louvre, made we wonder what inspired him there. And of course, the Sleeping Hermaphroditus ! For some reason, in all my dozens of visits, I have never stopped to look at it. So I shall give the opening of the Wikipedia article:The Sleeping Hermaphroditus is an ancient marble sculpture depicting Hermaphroditus life size. In 1620, Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini sculpted the mattress upon which the statue now lies. The form is partly derived from ancient portrayals of Venus and other female nudes, and partly from contemporaneous feminised Hellenistic portrayals of Dionysus/ Bacchus. It represents a subject that was much repeated in Hellenistic times and in ancient Rome, to judge from the number of versions that have survived. Discovered at Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, the Sleeping Hermaphroditus was immediately claimed by Cardinal Scipione Borghese and became part of the Borghese Collection. The "Borghese Hermaphroditus" was later sold to the occupying French and was moved to The Louvre, where it is on display.And here are some views: the sensuously androgynous back, the considerably more explicit front, and a detail of the head. R.

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus has been described as a good early Imperial Roman copy of a bronze original by the later of the two Hellenistic sculptors named Polycles (working ca 155 BC);[1] the original bronze was mentioned in Pliny's Natural History.

Polycles (after): Sleeping Hermaphroditus. (1st century CE, Louvre)

— high front view of the above

— detail of the head

Wow, Vit, what new vistas open up in this study of ours! I don't think I've much more than heard the name of Genesis, but I was able to find the track and listen to it. I appreciated the extended watery instrumental opening, but could not understand many of the words until I found them separately online. Not my thing, but thank you anyway.

Wow, Vit, what new vistas open up in this study of ours! I don't think I've much more than heard the name of Genesis, but I was able to find the track and listen to it. I appreciated the extended watery instrumental opening, but could not understand many of the words until I found them separately online. Not my thing, but thank you anyway.Although a former English major, I'm afraid I've read virtually no Swinburne, but this one I very much enjoyed. Sort of Wildean air of decadent eroticism, but muted, so that the poem emerges with a strange pathos. It's in public domain, so let's post the whole thing!

HERMAPHRODITUS

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

I.

LIFT UP thy lips, turn round, look back for love,

Blind love that comes by night and casts out rest;

Of all things tired thy lips look weariest,

Save the long smile that they are wearied of.

Ah sweet, albeit no love be sweet enough,

Choose of two loves and cleave unto the best;

Two loves at either blossom of thy breast

Strive until one be under and one above.

Their breath is fire upon the amorous air,

Fire in thine eyes and where thy lips suspire:

And whosoever hath seen thee, being so fair,

Two things turn all his life and blood to fire;

A strong desire begot on great despair,

A great despair cast out by strong desire.

II.

Where between sleep and life some brief space is,

With love like gold bound round about the head,

Sex to sweet sex with lips and limbs is wed,

Turning the fruitful feud of hers and his

To the waste wedlock of a sterile kiss;

Yet from them something like as fire is shed

That shall not be assuaged till death be dead,

Though neither life nor sleep can find out this.

Love made himself of flesh that perisheth

A pleasure-house for all the loves his kin;

But on the one side sat a man like death,

And on the other a woman sat like sin.

So with veiled eyes and sobs between his breath

Love turned himself and would not enter in.

III.

Love, is it love or sleep or shadow or light

That lies between thine eyelids and thine eyes?

Like a flower laid upon a flower it lies,

Or like the night’s dew laid upon the night.

Love stands upon thy left hand and thy right,

Yet by no sunset and by no moonrise

Shall make thee man and ease a woman’s sighs,

Or make thee woman for a man’s delight.

To what strange end hath some strange god made fair

The double blossom of two fruitless flowers?

Hid love in all the folds of all thy hair,

Fed thee on summers, watered thee with showers,

Given all the gold that all the seasons wear

To thee that art a thing of barren hours?

IV.

Yea, love, I see; it is not love but fear.

Nay, sweet, it is not fear but love, I know;

Or wherefore should thy body’s blossom blow

So sweetly, or thine eyelids leave so clear

Thy gracious eyes that never made a tear—

Though for their love our tears like blood should flow,

Though love and life and death should come and go,

So dreadful, so desirable, so dear?

Yea, sweet, I know; I saw in what swift wise

Beneath the woman’s and the water’s kiss

Thy moist limbs melted into Salmacis,

And the large light turned tender in thine eyes,

And all thy boy’s breath softened into sighs;

But Love being blind, how should he know of this?

— Au Musée du Louvre, Mars 1863.

Jim wrote: "One more link in the chain from Pyramus and Thisbe into the modern era: It appears that Shakespeare's immediate sources, poems by Brooke and Painter were in fact essentially translations of Tommaso Guardait..."

Jim wrote: "One more link in the chain from Pyramus and Thisbe into the modern era: It appears that Shakespeare's immediate sources, poems by Brooke and Painter were in fact essentially translations of Tommaso Guardait..."From what I've seen, Jim, the Guardati story in question was of Romeo and Juliet. But did he also do a version of the Pyramus and Thisbe myth? I found the complete thing in a PDF, but can't be bothered to peer through the indices to several volumes in small print!

P.S. As an opera lover, you would also be interested to know (if you don't already) that the plot of Bellini's version of the R&J story, I Capuleti e i Montecchi, differs considerably from Shakespeare (until the end), because it comes from "an earlier Italian source." I may now assume that source to have been your Guardati.

Following a tip from Peter (4/59) about the Ovid Gallery in the New Chambers of Sanssouci Castle in Potsdam, I am posting the relief of Apollo and Daphne. It is by the brothers Johann David Räntz and Johann Lorenz Wilhelm Räntz, and was completed in 1774.

Following a tip from Peter (4/59) about the Ovid Gallery in the New Chambers of Sanssouci Castle in Potsdam, I am posting the relief of Apollo and Daphne. It is by the brothers Johann David Räntz and Johann Lorenz Wilhelm Räntz, and was completed in 1774.

Räntz brothers: Apollo and Daphne 1774 (Sanssouci)

Peter wrote: "The golden painted reliefs on the selection page, by the way, are taken from the Ovid Gallery in the New Chambers of Sanssouci Castle in Potsdam."

Peter wrote: "The golden painted reliefs on the selection page, by the way, are taken from the Ovid Gallery in the New Chambers of Sanssouci Castle in Potsdam."With many thanks for that link, Peter, I am posting the relief of Apollo and Clytie (turned into a sunflower) here. and the Apollo and Daphne back in Book I. They are by the brothers Johann David Räntz and Johann Lorenz Wilhelm Räntz, and were completed in 1774.

Räntz brothers: Apollo and Clytie, 1774 (Sanssouci)

— detail of the above

Kalliope wrote: "At first I thought the three women could represent the three graces, but Bacchus in the cave on the right shift the identification to the Minyas women."

Kalliope wrote: "At first I thought the three women could represent the three graces, but Bacchus in the cave on the right shift the identification to the Minyas women."I'm still trying to catalog this. Are you sure it's Bacchus? I am wondering if the subject is not the Judgement of Paris? R.

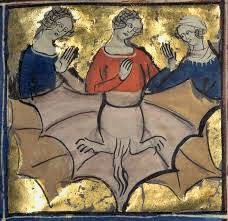

The two other MS pictures of the Minyades that I promised. The first, from a later-15th-century MS in the Bibliothèque Nationale, is hard to parse, since Bacchus appears just like a king, but with wings. But the three daughters are up there in their little room with (I think) bats already flying over their heads.

The two other MS pictures of the Minyades that I promised. The first, from a later-15th-century MS in the Bibliothèque Nationale, is hard to parse, since Bacchus appears just like a king, but with wings. But the three daughters are up there in their little room with (I think) bats already flying over their heads.

Anonymous illuminator: The Daughters of Minyas Reject Bacchus, later C15 (Paris BNF)

The second tiny picture, from the 14th century, leaves you in no doubt as to what happened to them!

Anonymous illuminator: The Daughters of Minyas Become Bats, later C14.

I wanted to post one more Corinth picture, though quite off-topic, just to show that he did not spend all his time poking fun as classical myths. This one is Cain piling rocks on the body of his brother Abel, whom he has just murdered. Its powerful violence has an added significance: it was painted in 1917. R.

I wanted to post one more Corinth picture, though quite off-topic, just to show that he did not spend all his time poking fun as classical myths. This one is Cain piling rocks on the body of his brother Abel, whom he has just murdered. Its powerful violence has an added significance: it was painted in 1917. R.

Corinth: Cain, 1917 (Düsseldorf)

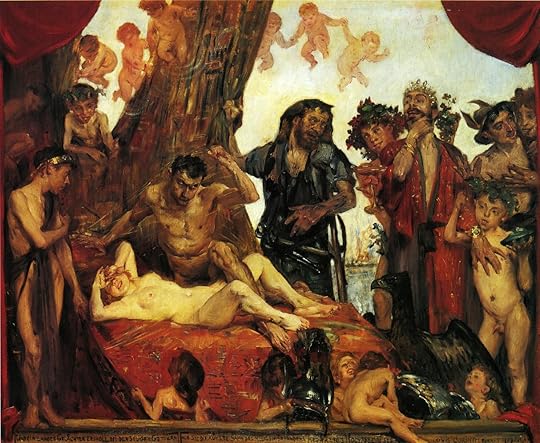

Checking back on Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) after Peter's post #31, I came upon a few Ovidian subjects. But the only other one immediately relevant to Book IV is his Homeric Laughter, which is the story of Vulcan catching Mars in adultery with his wife Venus. Rather than Ovid, though, Corinth gets this from Homer's Odyssey, where it is another story-within-a-story, told by King Alcinous on the island of the Phaeacians to entertain Odysseus. But it is the same subject, with the same outcome: that the adulterous pair become the laughing-stock of the other gods. R.

Checking back on Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) after Peter's post #31, I came upon a few Ovidian subjects. But the only other one immediately relevant to Book IV is his Homeric Laughter, which is the story of Vulcan catching Mars in adultery with his wife Venus. Rather than Ovid, though, Corinth gets this from Homer's Odyssey, where it is another story-within-a-story, told by King Alcinous on the island of the Phaeacians to entertain Odysseus. But it is the same subject, with the same outcome: that the adulterous pair become the laughing-stock of the other gods. R.

Corinth: Homeric Laughter, 1909 (Munich)