Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 161-180 of 419

Thumbing through images of Maenads or Bacchantes on the web, I notice that they are bracketed by two quite distinct extremes, representing in turn the ambivalent attitudes of men towards women.

Thumbing through images of Maenads or Bacchantes on the web, I notice that they are bracketed by two quite distinct extremes, representing in turn the ambivalent attitudes of men towards women.1. Pretty Women. The girls-having-a-party type, letting fall some of their inhibitions (and clothing too), but still somewhat decorous. Almost all these representations, though of women by themselves, are depicted in the way men would like to see them: full of youthful grace and energy, and quite adorable. One example of this type is this little terracotta by Claude Michel (Clodion) in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts:

Clodion: Two Dancing Bacchantes and a Putto, 1800 (Boston MFA)

2. Terrifying Women. These are the Bacchae of Euripides, women who have taken their destiny into their own hands to live in a world that is primitive, feral, and dangerous. These are the women who dismembered Pentheus. Again, it is men who mostly paint them, but they call upon a deep-seated fear of womankind. This Bacchic priestess by John Collier is by no means the most violent, but she clearly knows herself and will take no compromise:

Collier: The Priestess of Bacchus, 1885–89.

Another early representation of Pyramus and Thisbe. Although the names are given in Greek, this is in fact a Roman mosaic, from I think the third century CE, in Paphos, Cyprus.

Another early representation of Pyramus and Thisbe. Although the names are given in Greek, this is in fact a Roman mosaic, from I think the third century CE, in Paphos, Cyprus.

Roman mosaic: Pyramus and Thisbe, C3 CE (Paphos, Cyprus)

Jim wrote: "Pyramus and Thisbe in opera: As it happens, there has been a rare event recently in Toronto: the production of an opera by a Canadian composer. Barbara Monk Feldman's opera Pyramus and Thisbe..."

Jim wrote: "Pyramus and Thisbe in opera: As it happens, there has been a rare event recently in Toronto: the production of an opera by a Canadian composer. Barbara Monk Feldman's opera Pyramus and Thisbe..."How wonderful to know of this, Jim! Unfortunately, there are only snippets available on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4IaT...

—plus a five-minute behind-the-scenes documentary:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-9Td...

Both combine to show that this is a deeply serious work that has been given a committed staging by the Canadian company.

My searches also turned up an much earlier operatic setting that is frankly comic, written by John Frederick Lampe in 1745. The music is mainly parody Handel and other composers of the time, but it is enjoyable. The 13-minute clip contains only excerpts in sound only, but it is well presented, with a very helpful note:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJNg4...

And, just for the sake of completeness, a reminder of the Britten setting in his Midsummer Night's Dream:

https://youtu.be/QDy3FlUczNg?t=7251

Kalliope wrote: "What looks like a viola may not be so—the inwards curve is too exaggerated."

Kalliope wrote: "What looks like a viola may not be so—the inwards curve is too exaggerated."I looked at several photos of violas da gamba from the 17th century, and find that they do indeed tend to have tighter waists, and thus a deeper cut-in than modern cellos. But I agree that the Velasquez object is unusually so, and the finger-board seems a little too slender. But …

Three things make me inclined to disbelieve the "object used in weaving" explanation. First, that is is clearly a hollow construction with thickness. Why, if not as a sound box, for resonance? Second, that it is in the wrong room. The space for technical apparatus is in front; this is in the back, up the steps, and everything else there has to do with art, not technology. And third, even if the object was something else, it cannot have been very commonplace. Velasquez must have known that his audience would have assumed the musical connection—would have noted it, actually, even if they knew that the object was in fact something else.

I can't access the book you mentioned, so for me the jury is still out. R.

Kalliope wrote: "Yes, of course it is the Arachne story, and so is the Velázquez. What I want to explore is the possible conflation of the two iconographies."

Kalliope wrote: "Yes, of course it is the Arachne story, and so is the Velázquez. What I want to explore is the possible conflation of the two iconographies."Which two iconographies do you mean? The Minerva/Arachne one plus the presence of actual weavers, presumably? The Europa connection comes, as I thought, straight from Ovid.

Perhaps you made a typo when copying down the date of the Rubens. The Virginia Museum site places it definitely as 1636–37, i.e. as part of the Torre de la Parada commission. Which means that Velázquez would have known it. R.

Brilliant, Nora! I assume you teach this, as well as translate it? You are certainly the teacher here. R.

Brilliant, Nora! I assume you teach this, as well as translate it? You are certainly the teacher here. R.

The Rubens sketch IS the Arachne story, isn't it? One of the designs for the Torre de la Parada. Pallas is falling on Arachne and attacking her with a shuttle. Not in this Book, so I haven't come to it, but doesn't Ovid himself mention the weaving of the Europa picture as one of Arachne's most provocative accomplishments? R.

The Rubens sketch IS the Arachne story, isn't it? One of the designs for the Torre de la Parada. Pallas is falling on Arachne and attacking her with a shuttle. Not in this Book, so I haven't come to it, but doesn't Ovid himself mention the weaving of the Europa picture as one of Arachne's most provocative accomplishments? R.

I think we only skipped over the Minyades, Kalliope, because Ovid himself skips; itis only after their three (or is it four?) stories that thir own tale comes to fruition. I had collected a couple of different MS illuiminations to post later, but not any of the later things that you found. Like you, I especially like the Picasso.

I think we only skipped over the Minyades, Kalliope, because Ovid himself skips; itis only after their three (or is it four?) stories that thir own tale comes to fruition. I had collected a couple of different MS illuiminations to post later, but not any of the later things that you found. Like you, I especially like the Picasso.I am puzzled by the ceramic plate. I can understand your first identification of the Three Graces. For what on earth are these three bourgeoises doing outside with their clothes off when they are clearly described as inside getting on with their work? Is there not some other story that would explain the presence of Bacchus?

Incidentally, has anyone made the comparison between these three and Martha the sister of Lazarus, who also stayed back to do her chores instead of following the charismatic religious leader?

And I am also intrigued by your Rubens. Rather before Velasquez, of course, but could the Spaniard have known it? Or more likely, might both have been depicting the same source or scenario, which is now lost to us? R.

Nora wrote: "Will someone, please, post that mosaic for me?"

Nora wrote: "Will someone, please, post that mosaic for me?"I already did, Nora; it is the third image in post 24 above. Not a mosaic, though, but a wall painting. You're right, a little later than the Met, but not even by 100 years. I don't know if the Pompeii painter got his ideas from Ovid, or if they were both following some earlier source.

Which raises a question. We have been concentrating a lot on the reception of Ovid from the Middle Ages onwards, but what do we know about his reception in his own time? R.

Nora wrote: "Many questions are on the table here…".

Nora wrote: "Many questions are on the table here…".Thank you very much, Nora. There can be so much new activity in this group that sometimes even the most direct questions can go unanswered. I really appreciate the seriousness of your reply. R.

Spurred by Peter's example, I have been glancing at several Corinth paintings. There are a couple I shall want to post when I get home.* I would not call him satirical as such, but certainly leaning towards Expressionism in that he depicts things are as they are, and even a little more so—a policy that seems to apply especially to his nudes! R.

Spurred by Peter's example, I have been glancing at several Corinth paintings. There are a couple I shall want to post when I get home.* I would not call him satirical as such, but certainly leaning towards Expressionism in that he depicts things are as they are, and even a little more so—a policy that seems to apply especially to his nudes! R. *Our daughter gave us our fourth grandchild this morning, and right now I am looking after the other three.

Peter wrote: "While the discussion as already progressed to the story of Priamus and Thisbe, my mind still circles around the introduction of Book IV."

Peter wrote: "While the discussion as already progressed to the story of Priamus and Thisbe, my mind still circles around the introduction of Book IV."About a week ago, I started looking at Maenad pictures in connection with the Pentheus story, but did not post them. Then somebody else mentioned P&T, and I just jumped to that. But you're right, there is a lot to look at in the couple of pages before.

Nietzsche's notion of Apollonian versus Dionysian is Aesthetics 101, and I had always assumed that the two were basically part of the pantheon, with Apollo clearly the more respectable of the two, but both with equal power. Reading Ovid, though, I get the very strong sense of Dionysus/Bacchus as a dangerous interloper, and his cult a threat to the established order. Interesting! R.

Kalliope wrote: "….the hymn that the Theban women are singing in honor of Bacchus.."

Kalliope wrote: "….the hymn that the Theban women are singing in honor of Bacchus.."Is this the hymn I was referring to in post #3? What is there in the text to indicate that it is a hymn, and not straight narration? And why do most of the translations not print it as such? R.

Peter wrote: "Returning Bacchantes by Lovis Corinth, oil on canvas, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal"

Peter wrote: "Returning Bacchantes by Lovis Corinth, oil on canvas, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal"That's one party I am glad to have missed! Do we get any sense of Corinth's intentions here? Is he intending any sense of irony? I have not seen enough of his work to form an impression. R.

No transcription necessary—just cut and paste! It is remarkable though, in comparison to other languages, how little Italian has changed since the early Renaissance. R.

No transcription necessary—just cut and paste! It is remarkable though, in comparison to other languages, how little Italian has changed since the early Renaissance. R.

Kalliope wrote: "What looks like a viola may not be so—the inwards curve is too exaggerated."

Kalliope wrote: "What looks like a viola may not be so—the inwards curve is too exaggerated."Yes, I noticed that, but assumed it was either an variant form of the instrument or artistic licence. Do report back if you find that reference.

And no, I did not mean it was an actual opera performance, but something involving both music and theatre (which would have had incidental music anyway). It would seem that the connecting theme, in the painting as in Ovid, is the weaving of stories, whether literally so or acting them out. R.

Kalliope wrote: "I like this painting of Thisbe listening through the crack on the wall."

Kalliope wrote: "I like this painting of Thisbe listening through the crack on the wall."Oh, so do I ! Once again, our postings crossed, but your choice is surely the best of the lot. R.

PYRAMUS AND THISBE IN ART. Your comments, RC, about the built-in melodrama of Ovid's telling of the Pyramus and Thisbe story made me wonder how it was handled in art. First, with the notable exception of the Poussin I showed in post 12 (where the main interest is in the landscape anyway), virtually no major artists of the stature or Titian or Rubens have handled the theme at all. Not much surprise for those of us who come to it through Shakespeare's parody; the story will forever seem a minor one. Secondly—and this did surprise me—there are a remarkable number of treatments of the subject, spread out over many centuries. And many of these do appear to be wildly melodramatic, as in the Abraham Hondius below, or placidly sentimental, as in the Frans Francken, which I nonetheless find rather beautiful.

PYRAMUS AND THISBE IN ART. Your comments, RC, about the built-in melodrama of Ovid's telling of the Pyramus and Thisbe story made me wonder how it was handled in art. First, with the notable exception of the Poussin I showed in post 12 (where the main interest is in the landscape anyway), virtually no major artists of the stature or Titian or Rubens have handled the theme at all. Not much surprise for those of us who come to it through Shakespeare's parody; the story will forever seem a minor one. Secondly—and this did surprise me—there are a remarkable number of treatments of the subject, spread out over many centuries. And many of these do appear to be wildly melodramatic, as in the Abraham Hondius below, or placidly sentimental, as in the Frans Francken, which I nonetheless find rather beautiful.

Hondius: Pyramus and Thisbe, 1660–75 (Rotterdam)

Francken (attrib.): Pyramus and Thisbe in a Wooded Landscape, c.1600 (private collection)

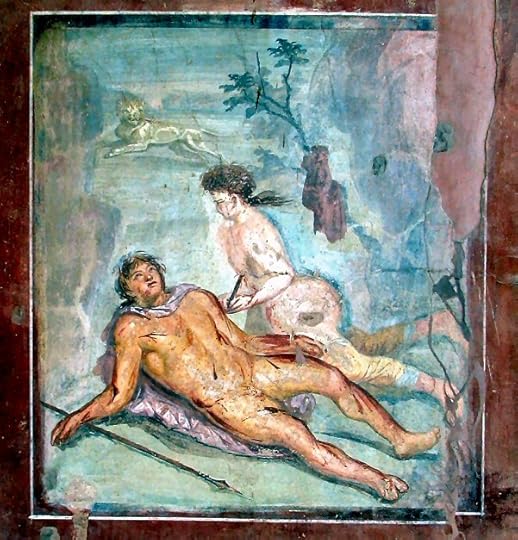

My next surprise was to find treatments of the subject spanning two millennia, from a Roman fresco im Pompeii to a student in an American High School. There is a certain potery in the fact that the fresco, about a love affair begun through a crack in a wall, should itself be preserved on a cracked wall!

Roman (Pompeii): Pyramus and Thisbe, c.70 CE (House of Loreius Tiburtinus)

Two now from Northern Europe. Lucas van Leyden's print has plenty of drama, and it even shows the lion in the background. The painting by Hans Baldung Grien has all the drama in the landscape (which might however have darkened more with time), but the figures are curiously placid—a strange combination of pathos with melodrama.

Lucas van Leyden: Pyramus and Thisbe, 1514.

Baldung Grien: Pyramus and Thisbe, c.1530 (Berlin)

From Holland, we have a drawing by Rembrandt (he is a major painter, but this is nay a sketch); it looks as though he was experimenting with different positions for Pyramus' body. And strongly Rembrandtesque, there is a night scene by Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674) who depicts not the drama but its epilogue: the discovery of the bodies.

Rembrandt: Pyramus and Thisbe, drawing, c.1636.

Bramer: The Finding of the Bodies of Pyramus and Thisbe, mid-C17 (Louvre)

The subject also appealed to neo-classicists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Here are two examples, German and French: an alabaster sculpture by Gebhard Boos, once more showing how much the third dimension accentuates the drama, and a painting by Pierre Gautherot, a painter about whom I know nothing except to admire his figure-painting and composition.

Boos: Pyramus and Thisbe, c.1775–80 (NY Met)

Gautherot: Pyramus and Thisbe, 1799.

Two final examples. The painting by William Waterhouse (whose iconic Echo and Narcissus I posted at 3/91) differs from all the others in showing only Thisbe, and in an early stage of the story, listening through that chink in the wall. [Kalliope beat me to this, but I'll keep it in the sequence.] And something that has absolutely no claim to great art, an entry for a high-school project. But the drugs on the ground between the two teenagers show an imagination at work, making an ancient myth relevant to real problems today.

Waterhouse: Thisbe, 1909 (private collection)

"Jess W": Pyramus and Thisbe, 2013.

I thanked you for this elsewhere, but reading it again just brings home, as you say, the way the Renaissance not only conflated classical ideas with Christian ones but also shaped much of the way in which we see Ovid in later centuries. If I have been rather reluctant in earlier posts to see the full violence in Ovid, it is because this is my tradition (much diluted, of course), rather than the original world of Ovid himself.

I thanked you for this elsewhere, but reading it again just brings home, as you say, the way the Renaissance not only conflated classical ideas with Christian ones but also shaped much of the way in which we see Ovid in later centuries. If I have been rather reluctant in earlier posts to see the full violence in Ovid, it is because this is my tradition (much diluted, of course), rather than the original world of Ovid himself.And talking of originals, you have inspired me to look this up in Italian. Many of our members seem fluent in several languages and may appreciate it. But the Mortimer is a superb rendering. R.

Apollo, s'anchor vive il bel desio

che t'infiammava a le thesaliche onde,

et se non ài l'amate chiome bionde,

volgendo gli anni, già poste in oblio:

dal pigro gielo et dal tempo aspro et rio,

che dura quanto 'l tuo viso s'asconde,

difendi or l'onorata et sacra fronde,

ove tu prima, et poi fu' invescato io;

et per vertú de l'amorosa speme,

che ti sostenne ne la vita acerba,

di queste impressïon l'aere disgombra;

sí vedrem poi per meraviglia inseme

seder la donna nostra sopra l'erba,

et far de le sue braccia a se stessa ombra.

Thanks, RC; and also for the Petrarch you posted in Book I, which is really lovely. Do you have it in Italian also? R.

Thanks, RC; and also for the Petrarch you posted in Book I, which is really lovely. Do you have it in Italian also? R.