Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 261-280 of 419

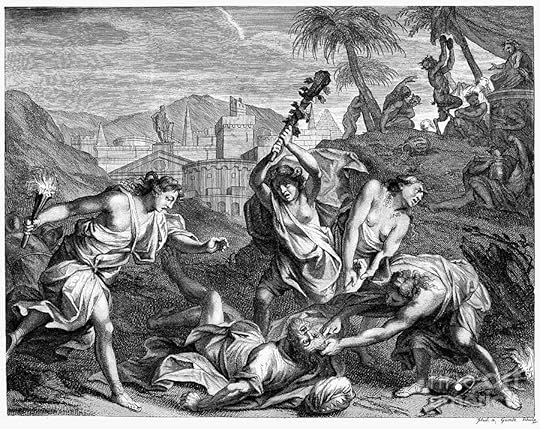

PENTHEUS IN ART. The subject of the Death of Pentheus is not a common one in art, but it spans all periods. Here are a few of them, though I can't find out all the details.

PENTHEUS IN ART. The subject of the Death of Pentheus is not a common one in art, but it spans all periods. Here are a few of them, though I can't find out all the details.

Attic bowl attributed to Dourix, c.480 BCE. Fort Worth, Kimbell Museum.

Roman fresco, 60–79 CE. Pomepeii, House of the Vettii.

Medieval manuscript. London, British Library.

I am amused by the relative decorum of the manuscript illumination, with everybody so deautifully dressed; only the bloody clubs suggest the horror of the scene.

Moving forward to the 18th century, then, I am struck by the classicizing quality of these and a number of other versions that I did not choose to post. Yes, it is a classical subject, whether taken from Ovid or the Bacchae of Euripides, but the treatments by the to-me-anonymous engraver or the great Jacques-Louis David seem to belong stylistically to an earlier century than their own.

Copper-plate engraving, 18th century.

Jacques-Louis David: Death of Pentheus, c.1775. Private collection.

Which is why I am posting two view of this painting by the contemporary Scottish artist Paul John Reed. Look at it quickly, and you would say Victorian, harking back to a style of a couple of centuries before that. But no, the date is 2002. Only when looking at the faces do you see that the Pentheus is surely a portrait of someone contemporary and real. And those women! This is far from the most violent version, yet there is an intent in those eyes that is very scary indeed. R.

Paul John Reed: Pentheus, 2002. Perth & Kinross Council.

- detail of the above.

P.S. There is an hilarious post on a site called The Toast, with about a dozen pictures of women murdering men. The opening sentence will give you the tone: "One of the greatest aspects of ancient Greek civilization was the persistent belief that there was nothing women liked better to do than assemble a gang, air their tits out, and roam the countryside beating men to death."

Back to an older topic: I can't believe that no one has posted this. Although only a sketch, it surely has everything—except, oddly, any indication that I can see of the infant Bacchus. Note that here too Jupiter is accompanied by his eagle, conveniently carrying his Grade B thunderbolts. R.

Back to an older topic: I can't believe that no one has posted this. Although only a sketch, it surely has everything—except, oddly, any indication that I can see of the infant Bacchus. Note that here too Jupiter is accompanied by his eagle, conveniently carrying his Grade B thunderbolts. R.

Rubens: The Death of Semele. Before 1640. Brussels, MBA.

Kalliope wrote: "The section on Pentheus, and again, the way we arrive at this episode, is very disconcerting."

Kalliope wrote: "The section on Pentheus, and again, the way we arrive at this episode, is very disconcerting."Would you care to elaborate a little, Kall? What in particular disconcerts you? The story is another quite brutal one, yes, but then Pentheus went out of his way to diss a god. The manner of arrival is certainly circuitous, first via Tiresias, and then by means of the quite extensive story of Acoetes. But why should this disconcert you?

I am interested that Pentheus should meet his fate at the hands of women. Indeed, the same thing would happen to Orpheus, whom we shall encounter later. Is this a myth supporting female empowerment? Or are the Bacchantes/Maenads a male-conceived example of what happens to women when they give in to their animal urges, essentially little different from Actaeon's hounds? R/

Kalliope wrote: "Alexandre Cabanel. Echo. 1874."

Kalliope wrote: "Alexandre Cabanel. Echo. 1874."Now that one is entirely new to me. But how beautiful!

It is a great pity that the success of Courbet, Manet, and later the Impressionists has almost wiped the more academic traditions of French art off the map. My local art gallery (one of them), the Walters in Baltimore, is one of the few places I know that displays quite a few. And clearly the Met—though I don't recall ever having seen this there. R.

Czarny wrote: "I beg to disagree..."

Czarny wrote: "I beg to disagree..."Sorry, I don't see the force of what you are saying. I was not criticizing Ariadne auf Naxos as an opera, merely saying that the role of Echo in it bears no relation to the tragic figure in Ovid. Mostly she sings in a trio with Naiad and Dryad, distinguished from them only by occasional solo lines which are repetitions of other people's lines—a literal echo, or built-in musical canon as I said.

Elektra, of course, is deadly serious. Salomé, though Biblical, takes the story way over the top, though that is Oscar Wilde's doing, which Strauss merely magnified. Ariadne, on the other hand, is a deliberate mixture, a piece of opera seria introduced by a backstage comedy and then interrupted by interludes of traditional farce. You are right that the serious parts contain some powerful music and can be quite serious indeed. I have done two productions of it, and performed in another, and find this particular balance between serious and comic quite fascinating.

But that is not at all what I was talking about in my remark about Echo. R.

Kalliope wrote: "As the pictorial implications of the Narcissus story - as well as the reversal of genders seem to me a very challenging theme for painters. I have explored a bit more...."

Kalliope wrote: "As the pictorial implications of the Narcissus story - as well as the reversal of genders seem to me a very challenging theme for painters. I have explored a bit more...."Indeed you have. I like the Talbot Hughes, partly because of the wonderful way she seems to be listening to her own echo, but mainly for the wonderful art nouveau motifs on her dress. I also like the fact that, by lying on what looks like another stream bank, she is echoing the pose of the unseen Narcissus.

As to the Lafontine, I suspect it has more to do with the lowercase-e echo than the Ovidian one. In talking of opera, I might have mentioned Echo characters in, say, Cavalli's La Calisto and Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos, but they are not so much mythological personages as musical devices, providing a built-in canon. R.

Kalliope wrote: "And so that we do not erase Echo from these pages... "

Kalliope wrote: "And so that we do not erase Echo from these pages... "Even in these, Echo seems fated to be kept in the background. On the other hand, she is right in front of the Waterhouse painting I posted earlier (#91), although turned to throw the focus back to Narcissus. Here is a black and white illustration (1896) from the magazine The Studio by someone called Solomon J. Solomon, which at least treats the couple on a roughly equal basis. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "For those of us who are interested in tracing this poem's engagement with issues of gender and speech, the Echo/Narcissus story is fruitful."

Roman Clodia wrote: "For those of us who are interested in tracing this poem's engagement with issues of gender and speech, the Echo/Narcissus story is fruitful."Indeed it is! I love this entire post (#103). R.

NARCISSUS OPERA. The only opera I know of the story is Echo et Narcisse (1779, but twice revised), the last opera by Gluck. Until now, I had never heard a note of it, and still can't find out much about it—except that, like most operas of the period, it has a happy ending. But…

NARCISSUS OPERA. The only opera I know of the story is Echo et Narcisse (1779, but twice revised), the last opera by Gluck. Until now, I had never heard a note of it, and still can't find out much about it—except that, like most operas of the period, it has a happy ending. But……there is a lovely aria for Echo in a good video. The man with her is not Narcissus, but apparently his friend. I can't catch enough of the French to be sure what is going on, except that she is unhappy in love. There are no titles.

…there is a less sharp video of a complete production from 1987, directed by René Jacobs. The whole thing is available, but the cue I give here is to an ensemble in the middle which I think gives the flavor. The whole stage is both surrounded by mirrors and floored with them. There are subtitles in Spanish.

Both of these are so beautiful as to make me want to hear the whole opera. R.

And two more sculptures that came up in my search. The top one has a curious attribution. It is now thought to be a Roman copy of an earlier classical statue, subsequently restored and more or less extensively reworked by the Florentine sculptor Valerio Cioli. The lower one is an earlyish example of the fascination that 19th-century artists clearly had for the subject. R.

And two more sculptures that came up in my search. The top one has a curious attribution. It is now thought to be a Roman copy of an earlier classical statue, subsequently restored and more or less extensively reworked by the Florentine sculptor Valerio Cioli. The lower one is an earlyish example of the fascination that 19th-century artists clearly had for the subject. R.

Valerio Cioli: Roman statue of Narcissus. Recut c.1564. London, V&A.

John Gibson: Narcissus. 2nd quarter C19. Gallery of NSW.

Elena wrote: "Cellini's statue of Narcissus was lost and then rediscovered: art as an artful reflection of art...."

Elena wrote: "Cellini's statue of Narcissus was lost and then rediscovered: art as an artful reflection of art...."Elena, I did not know of the Cellini, but have since found it. Thank you. It is a strange piece to me, first because it is the only version I have seen so far that is vertical rather than horizontal, and second because it seems so unstable, as though the figure is melting off the rock on which he is vaguely sitting. In fact, I suppose, he is becoming as much flower as human! The face is striking, though. R.

Benvenuto Cellini: Narcissus. c.1546. Florence, Bargello.

Vit, thanks from me also. I recall having the book on my bedside table for months—I can still see the cover clearly—but for some reason, I never got far into it. You make me wish I had. R.

Vit, thanks from me also. I recall having the book on my bedside table for months—I can still see the cover clearly—but for some reason, I never got far into it. You make me wish I had. R.

Kalliope wrote: "Such delicacy in its ambiguity."

Kalliope wrote: "Such delicacy in its ambiguity."Oh yes indeed! Much influenced by Matisse, but still her own. I like the way she incorporates the serpents into the ambi-sexual picture.

I looked for this myself, to see what the colors are like. I couldn't find it, but I now see that it is probably a black and white print. Here is another of hers, called Tiresias II. R.

NARCISSUS IN ART. Not many, but they involve rather different artists from the kind we have mostly seen before. The top half of the Caravaggio is used on the cover of the Rolfe Humphries translation. The William Waterhouse has become a classic, and seems a posthumous flowering of Victorian realism—the Pre-Raphaelite style a full generation later. And both the works from the Tate offer new perspectives on the story, the Dalí wonderfully surreal, the Collishaw (appropriately a self-portrait; note the bulb release in his hand) disturbingly literal. R.

NARCISSUS IN ART. Not many, but they involve rather different artists from the kind we have mostly seen before. The top half of the Caravaggio is used on the cover of the Rolfe Humphries translation. The William Waterhouse has become a classic, and seems a posthumous flowering of Victorian realism—the Pre-Raphaelite style a full generation later. And both the works from the Tate offer new perspectives on the story, the Dalí wonderfully surreal, the Collishaw (appropriately a self-portrait; note the bulb release in his hand) disturbingly literal. R.

Caravaggio: Narcissus. 1595–97. Rome, Gall. Arte Antica.

William Waterhouse: Echo and Narcissus. 1903. Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery.

— detail of the above.

Salvador Dalí: Metamorphosis of Narcissus. 1937. London, Tate.

Mat Collishaw: Narcissus. 1990. London, Tate.

P.S. It strikes me as strange, though, that nobody has written a non-farcical opera on the Tiresias story. The picture below comes from a website called "CrossDreamers," which I imagine is for transsexuals, or for people wondering about sexual identity. Now opera deals with these issues all the time, in its use of girls as boys, men as older women, and the strange halfway voice of the countertenor. I could imagine a piece that would take the subject very seriously—but so far, it doesn't exist. R.

P.S. It strikes me as strange, though, that nobody has written a non-farcical opera on the Tiresias story. The picture below comes from a website called "CrossDreamers," which I imagine is for transsexuals, or for people wondering about sexual identity. Now opera deals with these issues all the time, in its use of girls as boys, men as older women, and the strange halfway voice of the countertenor. I could imagine a piece that would take the subject very seriously—but so far, it doesn't exist. R.

TIRESIAS OPERA. There is actually an opera based on Tiresias—distantly based. This is Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias), the 1945 setting by Francis Poulenc of the Surrealist play by Guillaume Apollinaire. A blatant farce, set in a highly imaginary Zanzibar, it is also a plea to have children and repopulate the country after the devastation of war. The Tiresias character is sung by a soprano and called Thérèse. Early on in the piece, she opens her blouse and her breasts, which turn out to be helium balloons, fly up to the flies. Later on, she dons a beard. And in the second act, it is the men of Zanzibar who start having the babies!

TIRESIAS OPERA. There is actually an opera based on Tiresias—distantly based. This is Les mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tiresias), the 1945 setting by Francis Poulenc of the Surrealist play by Guillaume Apollinaire. A blatant farce, set in a highly imaginary Zanzibar, it is also a plea to have children and repopulate the country after the devastation of war. The Tiresias character is sung by a soprano and called Thérèse. Early on in the piece, she opens her blouse and her breasts, which turn out to be helium balloons, fly up to the flies. Later on, she dons a beard. And in the second act, it is the men of Zanzibar who start having the babies!

There is a very funny production from the Lyon Opera on YouTube, though the video is a bit muddy. If you want only a sample—narrated in Eglish, what's more—take a look at the two-minute trailer; it is hilariously brilliant! R.

TIRESIAS ENGRAVINGS. Here are the two stages of Tiresias striking the copulating snakes and receiving a sex-change as a result. The first is once again by Hendrik Goltzius. The other is by Johann Ulrich Krauss. R.

TIRESIAS ENGRAVINGS. Here are the two stages of Tiresias striking the copulating snakes and receiving a sex-change as a result. The first is once again by Hendrik Goltzius. The other is by Johann Ulrich Krauss. R.

TIRESIAS TIME FRAME. Something has been bothering me since reading this, and I have only just worked out what. Isn't it the only story we have encountered so far where the metamorphosis is part of the back-story of the narrative, not its outcome? In my faulty memory of the story, I had assumed that Jove and Juno put Tiresias through the gender switches in order to settle their argument. But no, it is more a matter of "Why not ask Tiresias, as he has already been turned into a woman and turned back again?"

TIRESIAS TIME FRAME. Something has been bothering me since reading this, and I have only just worked out what. Isn't it the only story we have encountered so far where the metamorphosis is part of the back-story of the narrative, not its outcome? In my faulty memory of the story, I had assumed that Jove and Juno put Tiresias through the gender switches in order to settle their argument. But no, it is more a matter of "Why not ask Tiresias, as he has already been turned into a woman and turned back again?" I have a couple more things to post when I get home. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "This question of the obscene, the legitimately lascivious and the pornographic is one that I enjoy grappling with in relation to Latin and Renaissance poetry."

Roman Clodia wrote: "This question of the obscene, the legitimately lascivious and the pornographic is one that I enjoy grappling with in relation to Latin and Renaissance poetry."Indeed. And on a more practical level, it is something one must be sensitive to all the time when lecturing on racy subjects like so many of these stories are; you want to excite but not offend.

I can still be surprised, though. Ten days ago, towards the end of my course "Vagaries of Operatic Love," I gave a class planned to end with two cases of overt homosexuality in opera, one gay ond one lesbian. I thought I would lead into it with some examples of the very old tradition by which adolescent boys might be played by women in trousers, and older women played by men in drag. To my surprise, many in the class found the cross-dressing offensive, but did not turn a hair at the kissing cowboys of Brokeback Mountain. Go figure! R.

A few miscellaneous answers to things that have come in overnight.

A few miscellaneous answers to things that have come in overnight.64. Kalliope. Thank you for pointing out the source of that wonderful banner. I hadn't noticed it came from the Jordaens, but had certainly been wondering.

65. Ilse. I tend not to like Moreau in general, but this one I find especially repulsive, on account of its mass of detail that (to my mind) obscures whatever story he may be telling.

66. Elena. The fatal oath theme (in this case, to sacrifice the first live creature that he sees) also occurs in Mozart's Idomeneo who survives shipwreck only to be greeted by his son.

71. Kalliope. I recalled that someone had written about Handel's Semele before, but I couldn't recall who and when. While I agree that it lends itself to all sorts of updating, I just wish there were a version out there closer to the original aesthetic.

72. Kalliope. Thank you indeed for the Giulio, which I didn't know. I find its plethora of extra nudes (who? why?) confusing. I don't see the Juno figure still as an old hag; perhaps I need to look at larger scale.

73. Roman Clodia. You mention of the eagle reminded me that Kalliope had said that Jupiter appears in the Ricci picture twice. But surely the eagle (unlike, say, Europa's white bull) is a companion to Jupiter, not an avatar?

74. Roman Clodia. I had forgotten Amphytrion; thank you. You are right about Molière's play; there is also one by Kleist. However, this was a special case. Jupiter did not pretend to be anyone other than himself when wooing Semele, but I would like to know how nicely he judged it.

75. Roman Clodia. Giulio Romano was a pupil and later assistant of Raphael, and carried on his legacy, especially as a fresco painter. I don't know why you put "pornographic" in quotes; the engravings are indeed quite explicit. There is quite a good novel on the subject also, by Robert Hellenga: The Sixteen Pleasures. R.