Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 321-340 of 419

Yes, I've been toying with posting this Rembrandt myself, but there is so, so much, and this one seems especially unclassical. Which is precisely its interest, of course! It all seems so bourgeois, doesn't it? One wonder what Jupiter sees in this Europa—yet of course she is a familiar Dutch type, and presumably attractive by the standards of her time. Detail below. R.

Yes, I've been toying with posting this Rembrandt myself, but there is so, so much, and this one seems especially unclassical. Which is precisely its interest, of course! It all seems so bourgeois, doesn't it? One wonder what Jupiter sees in this Europa—yet of course she is a familiar Dutch type, and presumably attractive by the standards of her time. Detail below. R.

I have been looking at a number of Europa paintings on what you might call the Titian model: subject reclining on the bull, who is in the water moving left to right, billowing draperies, and attendant Cupids. And it strikes me that Titian is unique in having Europa lie almost on her back, with her thighs parted. No other version that I have seen does this, certainly not the ones by Luca Giordano (top right) and Francesco Albani (bottom left) that I show a detail of below. But I have seen something very similar in Titian's Danae (detail bottom right). So again, the question is Why? The soft porn to please a patron theory that I advanced before? Probably not much. Tying in to the other poésies? Possibly, though I would have to look at all the others. Or something to do with Europa's fertility? I don't know about that one. But did Jupiter make her pregnant, and if so, who were her offspring? R.

I have been looking at a number of Europa paintings on what you might call the Titian model: subject reclining on the bull, who is in the water moving left to right, billowing draperies, and attendant Cupids. And it strikes me that Titian is unique in having Europa lie almost on her back, with her thighs parted. No other version that I have seen does this, certainly not the ones by Luca Giordano (top right) and Francesco Albani (bottom left) that I show a detail of below. But I have seen something very similar in Titian's Danae (detail bottom right). So again, the question is Why? The soft porn to please a patron theory that I advanced before? Probably not much. Tying in to the other poésies? Possibly, though I would have to look at all the others. Or something to do with Europa's fertility? I don't know about that one. But did Jupiter make her pregnant, and if so, who were her offspring? R.

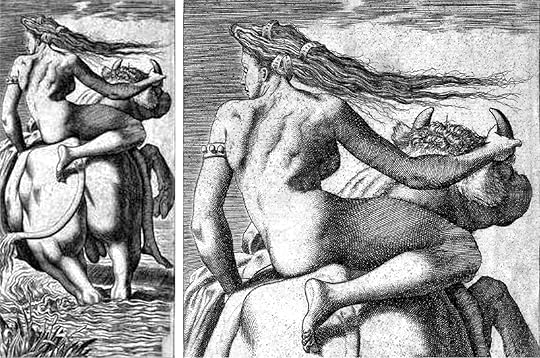

Here's a really odd one: an engraving in the Albertina, Vienna, by René Boyvin (1525–80). The only documentation I can find on it says that it's taken from one of the mythological paintings by Rosso Fiorentino at Fontainebleau, but I can't find the original. However, it is striking in a number of ways. One, a very obviously male bull! But two, a quite androgynous Europa, strongly muscled, and well able to take on the bull on its own terms. Very much as Michelangelo might have treated the subject, had he taken it on. R.

Here's a really odd one: an engraving in the Albertina, Vienna, by René Boyvin (1525–80). The only documentation I can find on it says that it's taken from one of the mythological paintings by Rosso Fiorentino at Fontainebleau, but I can't find the original. However, it is striking in a number of ways. One, a very obviously male bull! But two, a quite androgynous Europa, strongly muscled, and well able to take on the bull on its own terms. Very much as Michelangelo might have treated the subject, had he taken it on. R.

Kalliope wrote: "We have so far the Beckmann (54), the Picasso and the Lipschitz (both 136)."

Kalliope wrote: "We have so far the Beckmann (54), the Picasso and the Lipschitz (both 136)."I added the post numbers to your list for reference. I also posted the Ustyuzhanin (50). And now you have the Serov (138). Europa is an especially powerful subject, since it engages with forces more powerful than mere storytelling. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roman marriage ritual actually played out the 'abduction' scenario hence the carrying of the bride over the threshold of the new husband's house which we theoretically retain."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Roman marriage ritual actually played out the 'abduction' scenario hence the carrying of the bride over the threshold of the new husband's house which we theoretically retain."Very interesting! I thought I might be on to something; it is good to have it confirmed. It is so long since I saw Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, that the Sabine reference surely rolled right over me.

If you think of it, there is always something uncomfortable about the idea of marriage, even today. And in a society where most brides were virgins and all were property, I would imagine that their mixed emotions would include at least an element of apprehension. R.

Thank YOU, Kalliope, for posting the Serov. I had encountered it on my search, but at a small scale it looked like a cartoon or a graphic novel, so I didn't bother to look at it at full size. I agree, it is splendid.

Thank YOU, Kalliope, for posting the Serov. I had encountered it on my search, but at a small scale it looked like a cartoon or a graphic novel, so I didn't bother to look at it at full size. I agree, it is splendid.Interesting that you should relate my conjecture about the Europa story and marriage to actual practical applications on furniture or ceremonial depiction. But I meant something more pervasive than that: an explanation for the ubiquity and resonance of seduction/abduction/rape scenes in the Metamorphoses and certainly in the later depiction of them. I suggest that they play out the fear of marriage/deflowering in many a young woman's mind, but also the possible rewards that such a state might bring.

It is easy to see how this would apply to the Europa story in particular. Its beginning is civilized and gentle, a reciprocated wooing. It then moves into the actual abduction—taking the bride away from her home, family, and friends—that is surprising certainly and even frightening. But it also explains why so many artists depict it almost as a triumph, and not just for Jupiter.

The marriage parallel also goes far to illuminate our discussion of the very different moral color put upon the stories by the #MeToo generation, renaissance artists, and Ovid himself. R.

One more, and then I am done (for now). Here are two Cubist versions of the story. The top one is by Picasso. I can find nothing more about it, but it certainly ties into his obsession with bulls (and women). Since both woman and bull are reduced to flat areas upon the canvas (or is it paper?), the two share a common substance.

One more, and then I am done (for now). Here are two Cubist versions of the story. The top one is by Picasso. I can find nothing more about it, but it certainly ties into his obsession with bulls (and women). Since both woman and bull are reduced to flat areas upon the canvas (or is it paper?), the two share a common substance.But this is nothing to what Jacques Lipschitz does in his 1938 sculpture, where the figure of Europa seems to be totally subsumed in that of the bull. No longer riding on his back, she seems to be clinging to his flank; you can see the outline of her bosom and her hair. And she is kissing him on the open mouth—but it looks almost as though he is devouring her. A violent, disturbing image, quite different from most of the others we have been looking at. R.

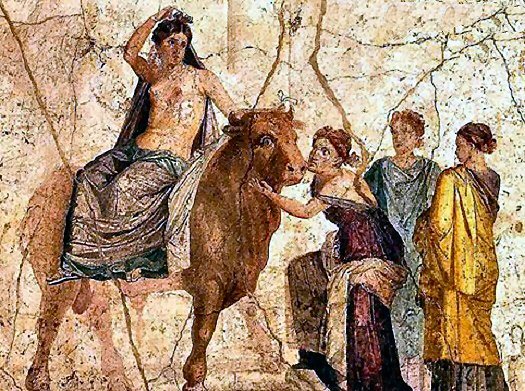

Going back to sources, here are two versions of the story from antiquity: a krater signed by Assteas (about 370-360 BCE) from Paestum, and a fresco (detail) from Pompeii (first century CE):

Going back to sources, here are two versions of the story from antiquity: a krater signed by Assteas (about 370-360 BCE) from Paestum, and a fresco (detail) from Pompeii (first century CE):

Neither of the two shows Europa especially afraid. The Assteas version has her in a pretty printed summer frock. Perhaps she is a little apprehensive, but not terrified. The artist keeps close to Ovid: one hand on the horn, her drape billowing behind her. The water is not represented, but instead depicted symbolically by the presence of Nereids or Tritons. Europa is no longer in her own world, but the mythological one.

The Roman fresco, of which this is only a detail, gives us that bare-breasted motif again, with no explanation for it. There are the three attendants here too, and they seem to be leading the bull, on which Europa sits like a princess in a procession. Or a bride. Which takes me to another Pompeii fresco:

I was not originally going to include it, partly because it is difficult to make out, but mainly because the setting is obviously urban, as though this were a procession to a temple rather than an abduction by sea; I wondered if the attribution was mistaken, and not Europa at all. But now I am not so sure. There is a ceremonial quality to all of these images that links them just as much as the abduction theme does. Once again, I wonder about the Europa story as a symbol of marriage…? R.

Kalliope, I could not make out everything in your Veronese image, so I looked up a detail, both from the original picture in Venice, and from an engraved variant version that makes it even clearer.

Kalliope, I could not make out everything in your Veronese image, so I looked up a detail, both from the original picture in Venice, and from an engraved variant version that makes it even clearer.

There is also a mirror-image of the composition in the National Gallery, London.

You are right about the licking of the foot, which you say is the artist's invention. As to that, yes, but Ovid does say he gives her kisses, though on the hands, so the switch to the foot is delightful, and suggestive. Ovid makes clear that these are but an earnest of what is to follow later. In Rolfe Humphries' rather free translation:

…and he, the loverThe renaissance terracotta that I showed earlier also has the kissing, but this time neither the hands nor the feet, but the bare breasts!

Gave kisses to the hands held out, rejoicing

In hope of later, more exciting kisses.

So what is it about all these breasts? Is it just soft porn to please the male patron? Are they justifying it by assuming that Europa was about to go bathing, and this was just the first stage of her undressing? Both Veronese pictures show one of Europa's attendants fiddling, it would seem, with one of her shoulder straps. Is she trying to cover her up again? Or more interestingly, is she actually un-covering her? In which case, the encounter with the bull is like a ceremony, a coming of age, as suggested by the Ukrainian exhibit I mentioned in my previous post. This fits in with the frequent presence of Cupids in paintings of the subject, so that both Jupiter and Europa come with their attendant train. Groomsmen and bridesmaids? R.

Browsing the web today, I came upon the striking image above. It is an ad for an exhibition in Kiev last year. Reading the text (below), I was struck how relevant the Europa myth still is today, to issues such as the status of women, politics, and—this surprised me—coming of age. R.

RAPE OF EUROPA opens at M17 Contemporary Art Centre in Kiev, Ukraine on February 16, 2017.

RAPE OF EUROPA is an international multimedia exhibition by visual artist Yana Lande in collaboration with the artists Anastasia Isachsen (Norway), Asta Bria (UK) and Natalka Osha (Ukraine). The exhibition includes 12 photo art works, an artefact in a form of a bull, video art and music.

The exhibition is a tender, touching yet strong story about coming of age told by contemporary means. The project is also an artistic comment to the current political situation in Ukraine.

Kalliope, I have a couple of verbal comments on your posting #120, with the Titian and Rubens. I will join in with some more pictures when I get back to my real computer.

Kalliope, I have a couple of verbal comments on your posting #120, with the Titian and Rubens. I will join in with some more pictures when I get back to my real computer.1. The Rubens copy is so close to the Titian in all but color, which is surprising, because he was a great colorist; it is the kind of thing you would get in a poor reproduction, or with a few bad decisions in Photoshop. Which is a useful reminder that, with all these reproductions, we have to extrapolate with the aid of things by the artist we have actually seen in the flesh.

2. Your quotation from Mandelbaum makes the whole abduction seem much more terrifying; he takes a strong interpretation of the Latin (the verb, I think, is "pavet," which—someone correct me—doesn't indicate the degree of alarm). I looked it up in Rolfe Humphries, which is all I have with me just now, and he makes the whole thing seem so much more gentle:

Is it time? Not quite. He leaps, a little playful,

On the green grass, or lays the snowy body

On the yellow sand, and gradually the princess

Loses all fear, and he lets her pat his shoulder,

Twine garlands in his horns, and she grows bolder,

Climbs on his back, of course all unsuspecting,

And he rises, ever so gently, and slowly edges

From the dry sand toward the water, further and further,

And swimming now, with the girl, trembling a little

And looking back to the land, her right hand clinging

Tight to one horn, and the other resting easy

Along the shoulder, and her flowing garments

Filling and fluttering in the breath of the sea-wind.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Elena wrote: "I didn’t know about all the Callisto paintings, Obviously lots of mixed feelings and anxiety about pregnancy"

Roman Clodia wrote: "Elena wrote: "I didn’t know about all the Callisto paintings, Obviously lots of mixed feelings and anxiety about pregnancy"Excellent point, Elena - I hadn't thought of that. In this case, it's ab..."

You are probably both right as a general matter of male fear of the mysteries of women, not to mention whatever fears women have for themselves. But in this case, it's much simpler: OMG, SHE BROKE THE CODE! R.

All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail . . . ?

All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail . . . ?He may have been mostly interested in landscape, but all the same he manages a really effective—and I would have said original—grouping of the figures in that descending diagonal. So utterly different from the Titian/Rubens approach, and quite beautiful. R.

Kalliope wrote: "Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17' and the following was shown..."

Kalliope wrote: "Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17' and the following was shown..."Indeed this is a lovely picture, Kalliope, and quite unknown to me. But it is hard to understand its storytelling at this scale, so I am providing a close-up:

At first, I thought that the Diana/Calisto pair was the couple at top left of this detail, one of whom seems indeed to be looking at the naked belly of the other. But no, Diana is the one with the yellow robe around her hips and the rather fashionable scarf, and Calisto [I can't use the double-L spelling to a Spanish-speaker] is the one being held by the two other nymphs several feet away and below her. So yes, subtle as you say, but a little too much so for clarity. The plethora of other nymphs is indicated in Ovid, and par for the course in painting, but what are those two doing at top left? R.

Thanks, RC. We will get to the Orpheus story later, I am sure. But it may be worth noting its status as the subject of the earliest operas we know (first decade of the 17th century), and the most composed subject for a good while thereafter. No doubt because the hero himself is a musician, and it is the beauty of his singing that wins over the powers of the underworld. R.

Thanks, RC. We will get to the Orpheus story later, I am sure. But it may be worth noting its status as the subject of the earliest operas we know (first decade of the 17th century), and the most composed subject for a good while thereafter. No doubt because the hero himself is a musician, and it is the beauty of his singing that wins over the powers of the underworld. R.

Jim wrote: "My point here is that the number of permutations in our experience can be limitless. "

Jim wrote: "My point here is that the number of permutations in our experience can be limitless. "That is true indeed. My point, which is complementary to it, is that our experiences are somewhat shaped by the artist who led us to them. Your response to Orfeo was conditioned by Gluck. It is this process of intermediation that so interests me as an interpreter. And, as an opera director, I am dealing with still more layers: the original story, the work of the composer and librettist, my own interpretation in staging it, the further contributions of the conductor and singers, and even the way I translate the text in the supertitles. R.

Jim wrote: "May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own...."

Jim wrote: "May I suggest that what we are dealing with here in this entire discussion are three separate entities, each of which is a thing unto itself and takes on a life of its own...."Thank you, Jim; a very useful taxonomy. I would divide your classification into four, however, separating the tellings by Ovid from the retellings by other artists who have read their Ovid. If we could show that any of these later versions entirely bypassed Ovid, that would be a different matter.

The point of your third category (or my fourth), I would imagine, is to encourage discussion, by saying that all points of view are equally welcome. True, and thank you for it. But I would suggest that our individual reactions are shaped by the particular source. We respond differently to the Callisto or Europa stories as told by Ovid from how we do when hearing Cavalli or looking at Titian. R.

Thanks, Historygirl. You are right: four verbs (slipped, faded, dropped, fell), whereas Latin could probably have done it all in one, though I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath.

Thanks, Historygirl. You are right: four verbs (slipped, faded, dropped, fell), whereas Latin could probably have done it all in one, though I think (without looking it up again) that Ovid uses a different verb for the laurel wreath.You mention that Latin is good for this sort of thing. Which makes me question the extent to which Ovid's contemporaries would have seen it as especially witty. When Alexander Pope writes:

Here Thou, great Anna! whom three Realms obey,we smile, partly because the linking of counsels of state to a cup of tea is so bathetic, and partly because the Latin-derived construct is unusual in English. But the four attributes of Apollo that fall are not so sharply contrasted, and the construction is relatively idiomatic. So I repeat: how witty would Ovid's readers have found it? R.

Dost sometimes Counsel take—and sometimes Tea.

HistoryGirl @77. Seems we were posting at the same time, and have made similar points. Can you possibly quote the Raeburn to add to this little anthology? R.

HistoryGirl @77. Seems we were posting at the same time, and have made similar points. Can you possibly quote the Raeburn to add to this little anthology? R.