Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 29, 2018)

Roger’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 301-320 of 419

ARPINO. Steve and Jim, I need to read the text again and think about the literary points you raise. Meanwhile, though, I can post Jim's picture. Painted around 1603–06 by Giuseppe Cesari, perhaps better known as the Cavaliere d'Arpino, it is a couple of generations later than the Titian. The fact that it is painted on copper rather than canvas may account for the exquisite clarity and detail. It is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Spectacular indeed! R.

ARPINO. Steve and Jim, I need to read the text again and think about the literary points you raise. Meanwhile, though, I can post Jim's picture. Painted around 1603–06 by Giuseppe Cesari, perhaps better known as the Cavaliere d'Arpino, it is a couple of generations later than the Titian. The fact that it is painted on copper rather than canvas may account for the exquisite clarity and detail. It is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Spectacular indeed! R.

SCULPTURE. Here is the Actaeon myth turned to sculpture by Paolo Persico, Angelo Maria Brunelli, and Tommaso Solari in the park of the Royal Palace at Caserta, Italy, in the last quarter of the 18th century. As the first picture shows, the artists tell the story in two groups, roughly comparable to the two Titian pictures, though reading right to left. Diana and her nymphs are in the foreground (i.e. on the right), with a couple of the women dipping a toe into the water. In the background (left) is the group of Actaeon being attacked by his hounds; I have added a close-up to show the marvelous detail. R.

SCULPTURE. Here is the Actaeon myth turned to sculpture by Paolo Persico, Angelo Maria Brunelli, and Tommaso Solari in the park of the Royal Palace at Caserta, Italy, in the last quarter of the 18th century. As the first picture shows, the artists tell the story in two groups, roughly comparable to the two Titian pictures, though reading right to left. Diana and her nymphs are in the foreground (i.e. on the right), with a couple of the women dipping a toe into the water. In the background (left) is the group of Actaeon being attacked by his hounds; I have added a close-up to show the marvelous detail. R.

TITIAN. Continuing with the Actaeon story, here is the pair of great Titian paintings of the subject. The first, of Actaeon spying on Diana, was finished aroung 1559, and is now in the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. The sequel, of Actaeon as a stag being pursued by his hounds and shot apparently by Diana (this bit not taken from Ovid), was started around the same time, but left unfinished. It is now in the National Gallery in London. R.

TITIAN. Continuing with the Actaeon story, here is the pair of great Titian paintings of the subject. The first, of Actaeon spying on Diana, was finished aroung 1559, and is now in the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. The sequel, of Actaeon as a stag being pursued by his hounds and shot apparently by Diana (this bit not taken from Ovid), was started around the same time, but left unfinished. It is now in the National Gallery in London. R.

ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704). There are several recordings on YouTube, but video gives slimmer pickings. However, take a look at this one from a performance at Versailles under Christophe Rousset. The link starts you in the middle of the scene with Diana's nymphs, which contains the most delectable music in the opera. After a duet and an aria, you will get the encounter of Actaeon and Diana, followed by his transformation into a stag.

ACTAEON OPERA. Early on in Book III comes the story of Diana and Actaeon. This has special interest for me because I have done two productions of Actéon, the opera-pastorale written around 1680 by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704). There are several recordings on YouTube, but video gives slimmer pickings. However, take a look at this one from a performance at Versailles under Christophe Rousset. The link starts you in the middle of the scene with Diana's nymphs, which contains the most delectable music in the opera. After a duet and an aria, you will get the encounter of Actaeon and Diana, followed by his transformation into a stag.Despite performing at Versailles, this is a modern production in rather low lighting. I hold no brief for the costuming of Actaeon, while those for the Nymphs frankly baffles me: why wear costumes at all, if they are going to reveal every bit of their bodies? And why put them in a metal mesh cage? I did just fine with all my singers in view and fully clothed; the music has sensuality aplenty! R.

I read quite a bit of Ovid in the rather weird British private education system of the time (early 1950s), between ages 11 and 14. But the emphasis was on language, not narrative. Then I changed majors, more than once actually.

I read quite a bit of Ovid in the rather weird British private education system of the time (early 1950s), between ages 11 and 14. But the emphasis was on language, not narrative. Then I changed majors, more than once actually.I returned to Ovid indirectly in my first career as an art historian, then in my second and longer one as an opera director. As I came upon various works based on Ovid—and there are a lot of them—I would go back to the source to check. But this is my first time reading the Metamorphoses from beginning to end.

Now I am retired from all the above, but very much engaged in teaching a series of courses for seniors that combine, in various ways, art, music, and literature. So the multi-disciplinary world of the Ovid legacy is a perfect match for my current interests, and every Book is full of new discoveries. Roger.

Speaking as one of the three moderators (but a newbie in the role), I must say I am pleased by the way the discussion has been developing since Book 1, with more contributors, and a nice balance between the dedicated classicists or historians, those who are more interested in the rich legacy of Ovid, and the many (I suspect) who are just enjoying the ride. Thank you, all! Roger.

Speaking as one of the three moderators (but a newbie in the role), I must say I am pleased by the way the discussion has been developing since Book 1, with more contributors, and a nice balance between the dedicated classicists or historians, those who are more interested in the rich legacy of Ovid, and the many (I suspect) who are just enjoying the ride. Thank you, all! Roger.

Historygirl wrote: "I am encountering Ovid with a blank slate and enjoying all of the new knowledge."

Historygirl wrote: "I am encountering Ovid with a blank slate and enjoying all of the new knowledge."What joy! R.

Jim wrote: "That said, I wonder how (or if) Dutch schoolmasters undertook to relate the Europa story to their students! "

Jim wrote: "That said, I wonder how (or if) Dutch schoolmasters undertook to relate the Europa story to their students! "How did schoolmasters relate the story to you, Jim? It's a valid question to ask of the whole Met, actually. Many of us knew, or knew of, a lot of these tales well before the age when we could fit them into the full body of adult knowledge. I knew the word "rape," for example, as something that happened in classical stories such as Proserpine or the Sabine Women, long before I knew of its sexual meaning—or the mechanics of sex, for that matter. R.

Lovely, Kalliope, both sets. Of course Claude, unlike his contemporary Poussin, is never (well, hardly ever) about his ostensible subject; it is always "Landscape with X and Y." Which is something you could also say about your three Italianate Lowlanders. And even about the Rembrandt, to a large extent.

Lovely, Kalliope, both sets. Of course Claude, unlike his contemporary Poussin, is never (well, hardly ever) about his ostensible subject; it is always "Landscape with X and Y." Which is something you could also say about your three Italianate Lowlanders. And even about the Rembrandt, to a large extent.Which doesn't prevent one from enjoying them as pictures, especially the beautiful balance of the Minderhout, as you say. R.

I'm jumping the gun, I know, but the story of Europa continues into the first couple of lines in Book III. Here they are in the translation by Charles Martin:

I'm jumping the gun, I know, but the story of Europa continues into the first couple of lines in Book III. Here they are in the translation by Charles Martin:And now, his taurine imitation ended,Martin takes liberties with the Latin, but that "exposed himself" hits the mark, and what a wonderful pun resides in the word "cowed"! R.

the god exposed himself for what he was

to cowed Europa on the isle of Crete.

And now a contrast. Here is the Europa story as told by English poet Simon Armitage in the collection After Ovid, which is on our group bookshelf. Very straightforward, except for the occasional use of unusual words: stirks, stot, allocked, bezzled, snod, bruff, and so on. Many of them can't be found in a dictionary, though one knows what they mean in context. But their Norse ring suspect that either they are farmyard words in one of the old dialects from the north of England, or are crafted to sound that way. What is interesting is that it brings the story down to the animal level, the opposite of the refinement shown by Titian and others. And yet this too has its pathos.

And now a contrast. Here is the Europa story as told by English poet Simon Armitage in the collection After Ovid, which is on our group bookshelf. Very straightforward, except for the occasional use of unusual words: stirks, stot, allocked, bezzled, snod, bruff, and so on. Many of them can't be found in a dictionary, though one knows what they mean in context. But their Norse ring suspect that either they are farmyard words in one of the old dialects from the north of England, or are crafted to sound that way. What is interesting is that it brings the story down to the animal level, the opposite of the refinement shown by Titian and others. And yet this too has its pathos.Jupiter and Europa

How very like him, Jove,

the father of the skies,

to send his silver son

down on a thread of light

to drive a team of stirks

across the lower slopes

towards the sea. A girl,

Europa, walked on the beach.

Then leaving in a cloud

his three-pronged fork, he went

to ground, dressed as a stot,

a bull, and allocked there

and bezzled with the herd.

His hide was snod and bruff,

a coat so suede and soft

and chamois to the touch,

and white, as if one cut

would spill a mile of milk.

His eyes were made of moon.

His horns were carved in oak.

Europa, capt and feared,

would not go near at first,

then offered to his lips

a posy fit to eat.

Jove nuzzled at her fist,

then ligged down in the sand;

in turns she smittled him

with plants, then climbed his back,

at which he sammed her up

and plodged into the tide;

on, out, until they swammed

beyond the sight of land.

With him beneath she rode

the fields of surf, above

the brine, because the sea

might gag or garble her,

or gargle in her voice.

The waves have not the taste

of wine. A girl at sea

is never flush with choice.

And where they beached, they blent.

Or where he covered her

beneath a type of tree

that tree was evergreen.

This is not Ovid's language of course, nor can I find any artworks that emphasize the farmyard aspect of the bull. Except perhaps the lovely sculpture by Frank Dobson that I posted earlier, moulded out of simple clay. R.

Here is the Europa of Guido Reni, painted 1638–40 and now in the National Gallery in London. It is quite significantly different from the others:

Here is the Europa of Guido Reni, painted 1638–40 and now in the National Gallery in London. It is quite significantly different from the others:

I am struck by its simplicity: nothing there except Europa, the bull, and one Cupid in the expanse of sea and sky. I am moved by its sweetness. But I am puzzled by the lack of distinction between this pagan subject and Christian art. The costuming, pose, and facial expression of Europa is strongly reminiscent of Raphael's saints, and you see the same thing in some of Reni's own religious pictures, such as the Mary Magdalene here in Baltimore; see the details below:

Erasmus+, the website I mentioned in an earlier post that lists over five dozen Europa images, notes the similarity as

…an intense iconographic parallel in forms and meaning of the classic Myth and the Christian values connected to the rape of the soul towards God to reach celestial beatitude. Reni mixes and transforms sacred and profane in a sort of well-done allegory of the salvation of the human soul.What? And yet John Donne's Holy Sonnet, "Batter my heart, three-person'd God," ends with the same image:

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,I would hesitate to attribute this meaning as the primary intention of Reni's painting, but I am struck nonetheless by how Protean a myth the story of Europa is, usable in the whole gamut of meanings from rape through apotheosis. R.

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Kalliope (#174) gave the passage in the painting described by Tatius that deals with Europa herself. I want to add the passage with which the description of this painting begins:

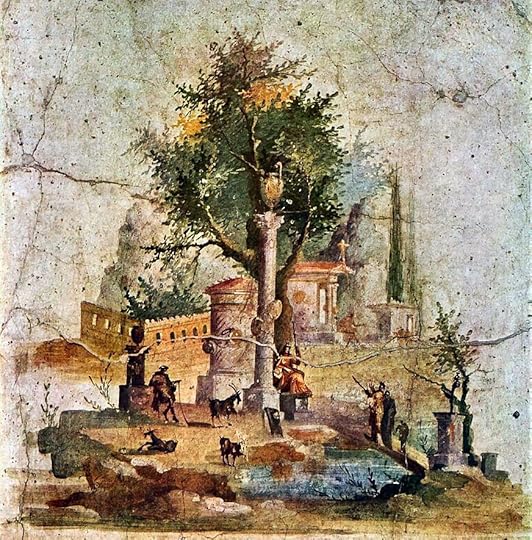

Kalliope (#174) gave the passage in the painting described by Tatius that deals with Europa herself. I want to add the passage with which the description of this painting begins:The painting was of Europa: the sea depicted was the Phoenician Ocean; the land, Sidon. On the land part was a meadow and a troop of girls: in the sea a bull was swimming, and on his back sat a beautiful maiden, borne by the bull towards Crete. The meadow was thick with all kinds of flowers, and among them was planted a thicket of trees and shrubs, the trees growing so close that their foliage touched: and the branches, intertwining their leaves, thus made a kind of continuous roof over the flowers beneath. The artist had also represented the shadows thrown by the leaves, and the sun was gently breaking through, here and there, on to the meadow, where the painter had represented openings in the thick roof of foliage. The meadow was surrounded on all sides by an enclosure, and lay wholly within the embowering roof; beneath the shrubs grass-beds of flowers grew orderly—narcissus, roses, and bays; in the middle of the meadow in the picture flowed a rivulet of water, bubbling up on one side from the ground, and on the other watering the flowers and shrubs; and a gardener had been painted holding a pick, stooping over a single channel and leading a path for the water.It's beautiful and extraordinarily detailed. But it only represents a very small part of the subject, equivalent to a strip at the left-hand edge of the Titian, say. Which made me wonder if there was any equivalent in Roman landscapes that have come down to us. Here are three (all Photoshopped to make them readable at this size):

Fresco from Pompeii, C1 CE.

Scene from the Odyssey, C1 BCE, Vatican.

Fresco from Boscotrecase, C1 CE, Naples.

Slim pickings, I'm afraid, although the third of these especially is quite beautiful. Perhaps there were paintings now lost that achieve some of the effects described by Tatius, but I doubt it. You can see the artists aiming for such an effect, but not achieving it in sustained form. A single pool, a pair of trees stand in for the kind of extensive landscape that Tatius describes.

We think of ekphrasis as describing an existing artwork in some other medium. such as poetry or (here) prose. But this makes me wonder if there is not another kind, what you might call ideal-ekphrasis, that uses words to paint the kind of picture that could not be achieved in the art of the time? So it is not "I saw this picture, and here's what it looked like," but "Imagine this, if you can…".

Nothing directly to do with Ovid, of course. But it reminded me that, up to now, we have not looked much at Ovid himself as a landscape painter in words. Yes, he uses shady groves and babbling brooks, the conventional attributes of the locus amoenus, or pleasant place. But the kind of detail given by Tatius? I think not, but may be wrong. This whole excursus has given me an impulse now to look. R.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Just a quickie, it's Horace Odes, book 3, poem 27"

Roman Clodia wrote: "Just a quickie, it's Horace Odes, book 3, poem 27"Thank you, RC. I don't know why I couldn't find it before. I was having a hard time with the Latin, but found a translation in the website Poetry in Translation. It is quite wonderful! I give the central stanzas (about a third of the whole) below. R.

So, Europa entrusted her snow-white form

to the bull’s deceit, and the brave girl grew pale,

at the sea alive with monsters, the dangers

of the deep ocean.

Leaving the meadow, where, lost among flowers,

she was weaving a garland owed to the Nymphs,

now, in the luminous night, she saw nothing

but water and stars.

As soon as she reached the shores of Crete, mighty

with its hundred cities, she cried: ‘O father,

I’ve lost the name of daughter, my piety

conquered by fury.

Where have I come from, where am I going? One

death is too few for a virgin’s sin. Am I

awake, weeping a vile act, or free from guilt,

mocked by a phantom,

that fleeing, false, from the ivory gate brings

only a dream? Is it not better to pick

fresh flowers than to go travelling over

the breadths of the sea?

If anyone now could deliver that foul

beast to my anger, I’d attempt to wound it

with steel, and shatter the horns of that monster,

the one I once loved.

I found a reference to the Horace Ode also, on an interesting website that I shall send you when I get home (I'm just about to teach a class on C19 French realism). But the citation must be wrong, since I could not find it, at least in Latin. If you track it down, please post a link or, better still, a translation of the relevant passage into some modern language. R.

I found a reference to the Horace Ode also, on an interesting website that I shall send you when I get home (I'm just about to teach a class on C19 French realism). But the citation must be wrong, since I could not find it, at least in Latin. If you track it down, please post a link or, better still, a translation of the relevant passage into some modern language. R.

Kalliope wrote: "Alas, I am not fond of Botero..."

Kalliope wrote: "Alas, I am not fond of Botero..."I neither. But I included him as an example of how totally an iconic image may be changed.

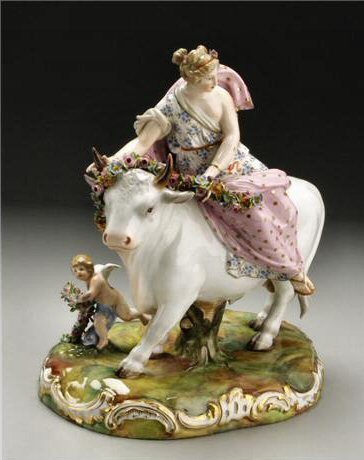

I agree with your favorites among the sculptures, at least #1, #2, and #10. I do have a sneaking fondness for that Meissen (#5), and am so puzzled by the violence of the Ricci (#4) that I wonder if Europa is even the correct attribution.

I am very struck by the recent correspondence between Historygirl, Roman Clodia, and yourself. I shall look at the Tatius when I get the chance. I think that, with our focus on Ovid, we just assumed that his text would be the source of any painting of stories that he tells. But clearly not necessarily so. And the ekphrasis adds a fascinating layer. R.

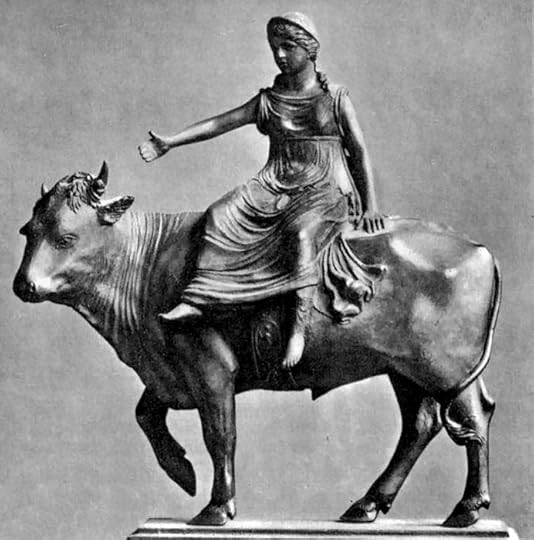

Czarny wrote: "The first two pictures are of sculptures that were made before Ovid wrote his work."

Czarny wrote: "The first two pictures are of sculptures that were made before Ovid wrote his work."Thanks, Czarny. It is just by chance that two of the three moderators are renegade art historians. You are of course right that we are reading because of Ovid, and the first two sculptures are pre-Ovidian. But what this has helped me realize—though perhaps it is obvious to others—is that Ovid himself was metamorphosing earlier myths. He emphasizes a narrative, even sometimes a romantic aspect. But some of the most seminal myths—and it seems that Europa is one—encapsulate more basic truths that we then see reflected in parallel with his telling of the stories. R.

Thanks for this, Elena. I like the Kauffman too, because it makes the two look like pupils in a boarding school, maybe a prefect encouraging a promising youngster. However, I do not understand your point about Callisto retaining a memory of some prior version of Artemis/Diana (who is really Zeus/Jupiter anyhow). R.

Thanks for this, Elena. I like the Kauffman too, because it makes the two look like pupils in a boarding school, maybe a prefect encouraging a promising youngster. However, I do not understand your point about Callisto retaining a memory of some prior version of Artemis/Diana (who is really Zeus/Jupiter anyhow). R.

Kalliope wrote: "The drapery blowing in the wind is in Ovid, but the cupids are not. I wonder about the Dolphins."

Kalliope wrote: "The drapery blowing in the wind is in Ovid, but the cupids are not. I wonder about the Dolphins."I have posted a query about cupids and so on before, but nobody picked up on it. My interest then was the similarity of the cupids to the putti accompanying Christian art.

In this case, the presence of the cupids presumably sanctifies the occasion as a romance rather than a rape. The dolphins are standard imagery to show that the demigods of the sea also lent their support. I imagine that, while Titian was very largely initiating a new pattern, most later artists were influenced by the art that came before them, rather than by their own readings of this or any other text. R.

I have been looking at a bunch of Europa sculptures. There is a wide range here, from heroic to Kitsch. But leaving aside the latter, one of the things that strikes me is how the stone or metal gives the character strength. Many of these show Woman Empowered, and few if any have a helpless victim.

I have been looking at a bunch of Europa sculptures. There is a wide range here, from heroic to Kitsch. But leaving aside the latter, one of the things that strikes me is how the stone or metal gives the character strength. Many of these show Woman Empowered, and few if any have a helpless victim.Anyway, just to get them off my desktop, here is a baker's dozen arranged in rough chronological order. I haven't time to do exact dates and attributions, nor will I comment in detail.

Further comments would be welcome. R.

1. Greek, 470–450 BCE. Louvre.

2. Terracotta, c. 470 BCE. Munich.

3. Bartolomeo Bellano, later 15th century.

4. Riccio, 1500. Budapest.

5. Meissen figurine, later 19th century.

6. Carl Milles, c. 1925. Cranbrook College. An unusually heroic Europa.

7. Lilli Finzelberg, 1930. Hamburg. Presented to the captain of the maiden voyage of the EUROPA.

8. Jacques Lipschitz, 1938.

9. Ruben Nakian, 1975.

10. Frank Dobson, 1946. I love its tenderness.

11. Asajero, 20th century. I can find out nothing about the sculptor, but include it as one of a very large number of such works, from the Art Deco period on, that emphasize the elegance of the Europa figure.

12. Fernando Botero. Contemporary. Don't ask me!

13. Fernando Botero. Contemporary.