John G. Messerly's Blog, page 21

November 2, 2022

Woke Political Opinions and the Suppression of Speech

By Laurence Houlgate, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. Reprinted with permission.

The Stop WOKE Act

On April 22, 2022, with the approval of Governor Ron DeSantis, the Florida legislature passed a bill that makes it illegal to publicly voice three opinions (ideas, beliefs, perspectives): (1) Some ethnic groups are inherently racist, (2) A person’s status as privileged or oppressed is determined by their race or gender, and (3) Discrimination is an acceptable way to achieve diversity in education and business.

DeSantis named the new law the “stop WOKE act” because (1), (2) and (3) are political opinions mainly spread by the far left of the Democratic Party, and (according to DeSantis) all woke political opinions are liberal or far-left and should be suppressed.

It came as no surprise that the WOKE act was soon struck down as unconstitutional. Tallahassee U.S. District Judge Mark Walker said in a 44-page ruling that the act “violates the First Amendment” and is “impermissibly vague.”

The First Amendment of the Constitution says “Congress [and the states] shall pass no law … abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.” My first thought when I saw the judge’s ruling was whether Governor DeSantis and those in the Florida legislature who voted for the act had carefully read the First Amendment. Most of the legislators went to law school. Did they not take a course in Constitutional Law and read Justice Hugo Black’s powerful admonition that when the Framers wrote the words “shall pass no law,” they meant “no law“?

There are two questions about freedom of woke speech that philosophers might ask: First, what does “woke” really mean? Second, aside from the constitutional issues, are there any plausible moral reasons for suppressing woke speech?

What is Woke Speech?

The word ‘woke’ has taken on a new meaning in the last decade. People are said to be woke if they are “aware of and actively attentive to important facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice)” (Merriam-Webster). Opinions and ideas are woke if they are about important facts and issues that make people be aware and actively attentive.

It makes sense to say that the ideas and perspectives of many great philosophers were woke in their time. Consider Socrates’ opinion that he is the wisest person in Athens because he is the only one who knows that he knows nothing (Apology); Plato’s idea that only philosophers should rule the city-state (Republic); John Locke’s idea that an absolute monarchy is a logical impossibility (Second Treatise of Government); Rousseau’s idea that man is born free, but is everywhere in chains (The Social Contract). Each of these ideas meets Merriam-Webster’s loose criteria for being woke.

Although the Merriam-Webster definition of ‘woke’ uses racial and social justice as an example of an important perspective or issue, the quoted definition says “especially issues of racial and social justice,” not “exclusively issues of racial and social justice.” This leaves plenty of room for other ideas or perspectives (for example, issues about abortion law) because the definition says nothing about what makes any idea or perspective ‘important’ other than “awakening” lots of people. But what is important to me may not be important to you. This is especially true about political and religious ideas. I am woke if I embrace the idea that women should have full control over their bodies, and you are woke if you deny this. All that matters is that our ideas are important, whatever they may be.

The broad Merriam-Webster definition of “woke” has been challenged recently by Florida governor Ron DeSantis. DeSantis does not want his conservative political and cultural views to be referred to as woke. Instead, he uses the word ‘woke’ in his speeches as a negative word. For DeSantis, labeling an idea or perspective as ‘woke’ is like labeling a jar of arsenic as poisonous. And this alone is sufficient for him to loudly declare that woke perspectives are wrong and should be suppressed.

Should Woke Speech be Suppressed?

This is where John Stuart Mill and his famed 19th- century book On Liberty (1859) enters the debate. If Mill was alive at the time the stop WOKE act was being debated in the Florida legislature, he would have vigorously argued that there no moral justification for making illegal the woke speech cited in (1), (2) and (3).

Mill’s argument for this is set out in chapter 2 of On Liberty (“Liberty of Thought and Expression”). Without going into a lot of detail, here is one of Mill’s arguments against the suppression of speech:

“(T)he peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race …If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error.”

Applying Mill’s argument to the (alleged) woke opinion #3 that “discrimination is an acceptable way to achieve diversity in education and business,” Mill’s first task would be to get the Florida legislature to admit that this opinion might be true. Mill writes that “to deny this is to assume our own infallibility.”

If it is admitted that no legislator is infallible, then it is possible that woke opinion #3 is true. If it is found to be true, then those who believe that it is false will be “robbed” by the Woke act of the opportunity to “exchange error for truth.” Although there are some politicians in our society who think it is a good thing to get others to believe a lie, this is usually good only for the politician and not for the populace at large.

On the other hand, if the woke opinion is false, then silencing the promulgation of the opinion and any debate about it ultimately robs the populace of the benefit gained from the “clearer perception and livelier impression” of the truth as it collides with the so-called erroneous woke opinion. This happens when we are forced to think critically and defend our ideas.

But none of this will happen if woke perspectives are silenced. Instead, non-woke political opinions will become dogma. Mill writes that citizens will eventually forget the rational basis for the approved non-woke opinions and they will revert to “the manner of prejudice, …[thereby preventing] the growth of any real and heart-felt conviction from reason or personal experience.”

Perhaps reversion to “the manner of prejudice” about their non-woke political opinions is what Governor DeSantis and his Republican loyalists want for the people of Florida.

Is this what Floridians want? Is this what you want?

____________________________________

References:

“What is the DeSantis Stop woke Act?” https://thehill.com/changing-america/...

“Federal Judge Temporarily Blocks DeSantis Stop Woke Law. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/08...

On Liberty. 1859. John Stuart Mill. Hackett Classics edition (1978). Hackett Publishing Company. 1978.

Understanding John Stuart Mill: The Smart Student’s Guide to Utilitarianism and On Liberty (2017). Laurence Houlgate, Kindle edition (Amazon).

October 31, 2022

Does Time Seem To Go Faster As We Age?

On first reflection, time does seem to pass more quickly as we age. I’m 67, and time seems to go faster now than when I was younger. As a child a day in school seemed to take forever, but so too did summer vacation. As an old professor, a school year seems to fly by. When I was a kid I thought something twenty years ago was prehistoric, now twenty years ago was 2002. And 2002 seems downright futuristic compared to the 1960s I remember.

But do we really experience time moving faster as we age? Probably not. BBC science writer Claudia Hammond’s recent article suggests that the idea that time accelerates as we age is mostly a myth. We measure time’s objective passing about the same at any age. But, as she says in her book, Time Warped: Unlocking the mysteries of Time Perception, the experience of time’s passing “depends on the time frame you are considering. In time perception studies, adults in a mid-life report that the hours and days pass at what feels like a normal speed; it is the years that flash by.”

Hammond believes this is because we assess time in two different ways. We can look at how fast time seems to pass in the present, or we can look retrospectively at how fast previous years or decades seemed to pass. Looked at retrospectively, time seems to go faster as we age. “The days still feel as though they pass at an average speed, but we’re surprised when markers of time indicated how many months and years have passed or at how quickly birthdays come round yet again.” But why? Hammond hypothesizes:

Part of the reason is that as we get older life inevitably brings fewer fresh experiences, and more routines. Because we use the number of new memories we form to gauge how much time has passed, an average week that doesn’t loom large in the memory gives the illusion that time is shrinking.

To combat this phenomenon Hammond suggests we fill our time with new experiences. On the other hand, “we do have to ask ourselves whether we really want to slow time down. If you look at the circumstances where evidence tells us that time goes slowly, they include having a very high temperature, feeling rejected and experiencing depression.”

Richard A. Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College has also found that the idea that objective time is speeding up as you age is illusory. “On the whole, most of us perceive short intervals of time similarly, regardless of age.” However, “when researchers asked the subjects about the 10-year interval, older subjects were far more likely than the younger subjects to report that the last decade had passed quickly.” So “Why … do older people look back at long stretches of their lives and feel it’s a race to the finish?”

Friedman’s answer is similar to Hammond’s. When you are younger “you are forming a fairly steady stream of new memories of events, places and people.” Then as an adult when “you look back at your childhood experiences, they appear to unfold in slow motion probably because the sheer number of them gives you the impression that they must have taken forever to acquire.”

But this is merely an illusion, the way adults understand the past when they look through the telescope of lost time. This, though, is not an illusion: almost all of us faced far steeper learning curves when we were young. Most adults do not explore and learn about the world the way they did when they were young; adult life lacks the constant discovery and endless novelty of childhood.

“Studies have shown that the greater the cognitive demands of a task, the longer its duration is perceived to be,” so perhaps ” learning new things might slow down our internal sense of time.” This may also be part of the solution to the apparent speeding up of time as we age:

if you want time to slow down, become a student again. Learn something that requires sustained effort; do something novel. Put down the thriller when you’re sitting on the beach and break out a book on evolutionary theory or Spanish for beginners or a how-to book on something you’ve always wanted to do. Take a new route to work; vacation at an unknown spot. And take your sweet time about it.

I think this is right. We can squeeze a bit more out of life by continually developing. After all, the art of staying young is in large part a matter of continually learning new truths, and unlearning old falsehoods.

October 27, 2022

Free Will and Henley’s “Invictus”

[image error]William Ernest Henley (1849 – 1903)

William Ernest Henley had a difficult life. His family was poor, his father died when he was young, and at age twelve tuberculosis necessitated the amputation of one of his legs below the knee. His other foot was later saved only after radical surgery. Henley was in and out of the hospital from the ages of eighteen to twenty-six, including a continuous three-year span from 1873-1875. He wrote “Invictus,” which is Latin for unconquered while recovering in the infirmary. It is one of the most memorable poems in the English language.

Invictus

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

The stirring finale of this poem is as fresh as the day it was written, still acting as a buttress against encroaching determinism. I have studied the philosophical issue of freedom enough to know that a sustained defense of free will is nearly impossible, but neither can its reverse be definitely established.

So we might as well believe in freedom. For if we have no choice but to believe in the freedom of will, then by necessity we will believe in it. And if we have a choice to believe in freedom of will, then by definition we are free. There is little to lose and much to gain by acting as if we are free as if we are masters of our fate and captains of our souls.1

_____________________________________________________________________

Note that this is a vast oversimplification. And so there is obviously a lot more to say about all this. I’m simply proposing that there are some advantages to believing in freedom of the will. There are also many disadvantages since we typically hold people responsible for things that are beyond their control. As I said there is so much more to say about all this.October 24, 2022

Marcus Aurelius: Life is Brief

[image error]

“Live not as though there were a thousand years ahead of you. Fate is at your elbow; make yourself good while life and power are still yours.” ~ Marcus Aurelius

I recently scribbled this quote on my youngest daughter’s birthday card. Just her luck, her father is a philosopher! Seriously though the fleeting, ephemeral nature of life is a basic tenet of Stoicism and Buddhism, a basic motif of Proust and Shakespeare. What is it about the passing of time that is so compelling yet disturbing, and what can we learn from it?

An 80-year lifespan is 960 months or about 29,000 days long. Think of that, an entire life. If you are middle-aged and will live another 40 years that’s only 480 months or about 15,000 days. And for someone my age with a life expectancy of maybe 15 more years, that’s 180 months or about 5500 days. This is shockingly brief.

The stream we are floating down, slowly, inexorably, and beyond our control is … life. We are thrown into the world, imagine endless possibilities if we are lucky and then, suddenly, time has passed. We can’t stop it, rewind it, or fast-forward it even if we want to. And what of our destination? Looking back on almost 60 years of living, I feel a kinship with Yeats:

When I think of all the books I have read, and of the wise words I have heard spoken, and of the anxiety I have given to parents and grandparents, and of the hopes that I have had … my own life seems to me a preparation for something that never happens.

Perhaps this is what’s so disturbing about time. It refers to a now unreal past, a vanishingly short present, all while leading to a future that quickly disappears. Perhaps something is amiss in life, and part of what’s missing manifests itself in time’s flow. Personal immortality has been proposed to ameliorate our worries, but I reject the comfort of charlatans, of purveyors of salve. As Diderot put it: “Lost in an immense forest during the night I have only a small light to guide me. An unknown man appears and says to me: ‘My friend blow out your candle so you can better find your way.’ This unknown man is a theologian.”

Today we have many cults from which to choose. But I reject them all. Instead, I will keep my candle, my little light of reason, even though I am lost in time. No longer in the Dark Ages, I will not be guided by the blind. I will be, as Buddha counseled, a lamp unto myself, guided by science, reason, and evidence.

October 21, 2022

Descartes to Kant in Two Pages

(Note. This was prepared for my students on the spur of the moment many years ago. Over 200 years of philosophy in 2 pages!)

Descartes wants to know what’s true. He begins by doubting everything and argues that knowledge derives from the certainty of the existence of one’s own consciousness and the innate ideas it holds. Primary among these innate ideas are mathematical ideas and the idea of a God. Upon this foundation, he claims all knowledge is built.

Locke argues that innate ideas are just another name for one’s pet ideas. Instead, he argues, knowledge is based on sense-data. Locke realizes that we only know things as we experience them, we don’t know the essence of the substances that make up the world. Retreating from the skepticism this implies, he accepts the common sense view that our perceptions correspond to external substances that are in the world.

Berkeley realizes that we can have perceptions without there being an external world at all. He believes that things exist only to the extent they are perceived, and thus non-perceived things don’t exist. All reality may be in the mind! Recognizing the implications of this radical philosophy, Berkeley claims that his God constantly perceives the world and thus the world is real after all.

Hume follows this thinking to its logical conclusion. We have perceptions, but their source is unknown. That source could be a god or gods, other powerful beings, substances, the imagination, etc. He also applies this skepticism about the existence of the external world to science, morality, and religion. Scientific knowledge is not absolute because there are problems with the idea of cause and effect as well as with inductive reasoning. Still, Hume believes that mathematics and the natural sciences are sources of knowledge.

Hume’s attack on religion is one of the most famous in the history of philosophy, and he ranks with Feuerbach, Marx, Nietzsche, and Russell as great critics of religion. His argument that miracle stories are almost certainly untrue is the most celebrated piece on that subject ever written.

For example, take the case of virgin births or resurrection from the dead. Such stories are found in many religions and throughout pagan mythology. But Hume asks whether it is more likely that such things actually happened, or that these are myths, stories, lies, deceptions, etc. Hume argues that it’s always more likely that reporters of miracles are deceiving you or were themselves deceived than that the supposed miracle actually happened. Lying and being lied to are common, walking on water and rising from the dead—well, not so much.

Hume’s philosophy set the stage for the greatest of the modern philosophers, a man who said that Hume had “awakened him from his dogmatic slumber.” This thinker wants to respond to Hume’s skepticism and show that mathematics, science, ethics, and the Christian religion are all true. His name was Immanuel Kant.

Kant was one of the first philosophers who was a professor. He was a pious Lutheran, a solitary man who never married, and the author of some of the most esoteric works in philosophy. Troubled by Hume’s skepticism, Kant looked at both rationalists like Descartes and empiricists like Locke, Berkeley, and Hume for answers. Kant believed that the problem with rationalism was that it established great systems of logical relationships ungrounded in observations. The problem with empiricism was that it led to the conclusion that all certain knowledge is confined to the senses.

Kant thought that if we accept the scientific worldview, then belief in free will, soul, God, and immortality was impossible. Still, he wanted to reconcile rationalism and empiricism, while at the same time showing that God, free will, knowledge, and ethics are possible. In fact, much of western philosophy since Descartes has tried to reconcile the scientific worldview with traditional notions of free will, meaning, God, and morality.

Kant’s Epistemology – Kant argues that rationalism is partly correct—the mind starts with certain innate structures. These structures impose themselves on the perceptions that come to the mind. In other words, the mind structures impressions, and thus knowledge results from the interaction of mind and the external world. Thus both the mind and sense-data matter in establishing truth, as the success of the scientific method shows.

Kant’s Copernican revolution placed the mind, rather than the external world, at the center of knowledge. What we can know depends upon the validity of what’s known by the structures of the mind. But is metaphysical knowledge justified? Can we know about the ultimate nature of things, things beyond our experience? Can we know if God, the immortal soul, or free will exists?

What he realized was that all we can know are phenomena, that is experiences or sense-data mediated by the mind. Since all our minds are structured similarly, we all generally have the same basic sensory experiences. But we cannot know “things-in-themselves,” that is, things as they actually are. Thus there is a gap between human reality—things as known to the mind—and pure reality—things as they really are.

To bridge this gap Kant proposes regulative ideas—self, cosmos, and God—which serve to make sense of our experiences. We must presuppose a self that experiences, a cosmos to be experienced, and a cause of the cosmos which is God. Kant grants that we can’t know if any of these things are true, but he thinks it is a practical necessity to act as if they are. We cannot have experiences without there being a knower, a known, and God. Since we do have experiences, Kant concludes that these regulative ideas probably correspond to real existing things.

Summary – Descartes was responding to the faith of the Middle Ages. His skepticism led eventually to the full-blown skepticism of Hume. Kant tried to reconcile Cartesian rationalism and Humean empiricism. He tried to harmonize science with religion, reason with ethics, and more. Whether he was successful is another question.

(Here is a two-page summary of Kant’s ethical theory. And here. is the theory in detail.)

October 17, 2022

“Voluntary Active Euthanasia”

[image error]

The Death of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787)

Dan Brock says his essay, “Voluntary Active Euthanasia,” discusses voluntary active euthanasia in cases “where the motive of those who perform it is to respect the wishes of the patient and to provide the patient with a “good death…”

The Central Ethical Argument for Voluntary Active Euthanasia –

The values supporting voluntary active euthanasia “are individual self-determination or autonomy and individual well-being.” Self-determination refers to persons being free to make decisions about their own lives. [Rather than governments, religious organizations, political groups, strangers, etc.] And this autonomy ought to extend to the end of life when persons worry about suffering and the loss of dignity. Individual well-being refers to situations in which individuals decide that “life is no longer considered a benefit by the patient, but has now become a burden.” In other words, their well-being is best served by dying. This does not imply that physicians must perform this act against their will.

Potential Good Consequences of Permitting Euthanasia – 1) respect individual autonomy (of about 50,000 persons a year in the US in this situation; 2) give reassurance to those who may want euthanasia in the future; and 3) it will relieve vast amounts of suffering.

Potential Bad Consequences of Permitting Euthanasia – Brock list 3 arguments: 1) performing is incompatible with the “moral center” of being a physician and thus patients would fear their physicians. B replies that patients should not fear that their physicians will kill them since E would be voluntary and the moral center of medicine should be self-determination and individual well-being not preserving life when persons have deemed they no longer want that. 2) E would weaken respect for life. (Do we respect life in our country?) Brock responds that he is skeptical here because: a) passive euthanasia has had no such consequences; and b) euthanasia would only be relevant in a small minority of deaths. 3) Legalizing voluntary euthanasia would lead down a slippery slope to involuntary euthanasia. Brock responds that this is the “last refuge of conservative defenders of the status quo.” When all your arguments against something have been defeated you simply say that this something will lead to something else.

My Commentary – While it is possible that doing x will lead to bad consequences, that is not enough of a reason not to do x. When in vitro fertilization was introduced in the 1970s, Leon Kass, later the head of President George W. Bush’s bioethics commission, wrote feverishly for years that this would undermine the value we place on human life. In the meantime, millions of persons have been born this way and nothing like that has happened. We don’t want to know if some terrible consequence is possible, rather we want to know if this consequence is plausible. And no one had done this.

Brock suggests a number of safeguards to minimize the chance of abuse. However the idea that one must be terminally ill—like the law demands in Oregon and Washington in the US—does not, according to Brock, respect self-determination. As Brock suggests, OR and WA can serve as test cases for such laws. Let’s see if society collapses because of euthanasia laws. Of course, this will not happen. In fact, the Netherlands has had the most liberal euthanasia laws on the books for years and it is one of the best, most civilized countries in the world.

October 13, 2022

Fluid vs. Crystallized Intelligence

Fluid and crystallized intelligence are elements of general intelligence, originally identified by Raymond Cattell. The concepts of fluid and crystallized intelligence were further developed by Cattell’s student John L. Horn. Here are Wikipedia’s definitions:

Fluid intelligence or fluid reasoning is the capacity to reason and solve novel problems, independent of any knowledge from the past. It is the ability to analyze novel problems, identify patterns and relationships that underpin these problems and the extrapolation of these using logic. It is necessary for all logical problem solving. Fluid reasoning includes inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Crystallized intelligence is the ability to use skills, knowledge, and experience. It does not equate to memory, but it does rely on accessing information from long-term memory. Crystallized intelligence is one’s lifetime of intellectual achievement, as demonstrated largely through one’s vocabulary and general knowledge. This improves somewhat with age, as experiences tend to expand one’s knowledge.

So the basic difference is that fluid intelligence involves our current ability to reason and to deal with complex information, while crystallized intelligence involves learning, knowledge, and skills acquired over a lifetime. Research has shown that these two factors of general intelligence peak at different times in life. Fluid intelligence peaks early in life, typically in the late teens or early twenties, while crystallized intelligence peaks much later in life, often in one’s sixties or seventies.

And recent research, using large online samples, reveals that specific mental capabilities peak at different times. Here are the ages at which various capabilities peak:

18-19: Information-processing speed peaks early, then begins to decline.25: Short-term memory gets better until around age 25.30: Memory for faces peaks and then starts to gradually decline.35: Short-term memory begins to weaken and decline.40s-50s: Emotional understanding peaks in middle to late adulthood.60s: Vocabulary abilities continue to increase.(If interested you can find many graphs about age and various mental capabilities here.)

While I am not an expert on this topic the findings above match my experience. I found that teaching symbolic logic became more difficult to teach as I aged but understanding and synthesizing philosophy became easier as the storehouse of my knowledge increased.

I’m not sure how this all relates to clichés like “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks” or “old people are set in their ways.” I am a lifelong learner who believes that unlearning old falsehoods is the essence of having a childlike, inquisitive mind. To keep learning we must fight against the mental grooves that accumulate with time. Still, I admit to being more open-minded—or impressionable if you prefer—when I was younger. As I’ve gotten older some ideas have simply been discarded and I don’t have the time or inclination to revisit them.

I suppose then that we need to strike a balance between being open to novel ideas and not discarding previous ones that were adopted after careful and conscientious deliberation. As the late Carl Sagan put it in one of my favorite books, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark[image error], “Keeping an open mind is a virtue—but … not so open that your brains fall out.”

October 10, 2022

“The Tragic Sense of Life”

I was re-reading a small part of Miguel de Unamuno‘s, Tragic Sense of Life (1910) when I came across these haunting lines:

Why do I wish to know whence I come and whither I go, whence comes and whither goes everything that environs me, and what is the meaning of it all? For I do not wish to die utterly, and I wish to know whether I am to die or not definitely. If I do not die, what is my destiny? and if I die, then nothing has any meaning for me. And there are three solutions: (a) I know that I shall die utterly, and then irremediable despair, or (b) I know that I shall not die utterly, and then resignation, or (c) I cannot know either one or the other, and then resignation in despair or despair in resignation, a desperate resignation or are resigned despair, and hence conflict.

…

For the present let us remain keenly suspecting that the longing not to die, the hunger for personal immortality, the effort whereby we tend to persist indefinitely in our own being, which is, according to the tragic Jew (Spinoza), our very essence, that this is the affective basis of all knowledge and the personal inward starting-point of all human philosophy, wrought by a man and for all men. And we shall see how the solution of this inward affective problem, a solution which may be but the despairing renunciation of the attempt at a solution, is that which colours all the rest of philosophy. Underlying even the so-called problem of knowledge there is simply this human feeling, just as underlying the enquiry into the “why,” the cause, there is simply the search for the “wherefore,” the end. All the rest is either to deceive oneself or to wish to deceive others; and to wish to deceive others in order to deceive oneself.

And this personal and affective starting point of all philosophy and all religion is the tragic sense of life.

Unamuno’s sublime description of the tragic sense of life is reminiscent of the sentiments of Blaise Pascal. Both writers convey a lostness regarding our place in an indifferent cosmos. When I used to teach existentialism—Unamuno is an early existentialist—students complained that it was both tragic and depressing. They saw little value in the longings of someone like Unamuno, or in Dostoevsky’s “suffering is the origin of consciousness,” or in Sartre’s “Life begins on the other side of despair.” Some even found Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning too depressing.

too depressing.

Now I do not believe there is any intrinsic value in suffering; I do not believe in pain, suffering, war, death, or in any of the other limitations and evils that surround us. But the recognition of how terrible, tragic, and absurd life is compared with how good it could be has a redeeming feature—the possibility that this recognition may motivate us to eliminate these evils. This is the value of Unamuno’s recognition of the tragic sense of life.

October 6, 2022

God Help Us All: Fending Off An American Theocracy

[image error]“God Help Us All: Fending Off An American Theocracy”

by MARK HARVEY

The trouble with theocracies is that they generally lead to crusades. And the trouble with crusades is that if you’re not of the right sect or denomination, you’ll end up crucified. Theocracies lead nowhere, bring great suffering on peoples, stifle creative thought, and have women covered or in the kitchen. They do anything but lead to paradise on earth. But they do give people a taste of hell.

Whether it’s the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Isis caliphate in Iraq and Syria, or The Islamic State of Iran, theocracies are inherently oppressive, and regressive. They subscribe to the idea that there is only one God, he is to be obeyed without question, and that those ruling in a theocratic government have some sort of manifest connection with that God.

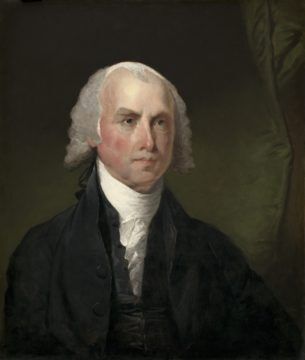

James Madison

James MadisonTo some degree, Americans have been spared the ravages of theocracies. We are perhaps most indebted to James Madison for that. Madison, sometimes called the father of the Constitution, understood well in advance of 1789 when the framers met in Philadelphia, that the new nation being formed needed to be free and clear of the factionalism so often created by religious zealots. In letters to his close friend Thomas Jefferson, Madison wrote, “When Indeed Religion is kindled into enthusiasm, its force like that of other passions is increased by the sympathy of a multitude….Even in its coolest state, it has been much oftener a motive to oppression than a restraint from it.”

I have no issues with religion per se. I think it genuinely helps some people navigate their lives and having a faith strong enough to maintain an unswerving optimism in the face of life’s hardships is even enviable. For the truly dispossessed and bereaved, a belief in God may be the last thing to cling to. Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of our great writers and a transcendentalist, called the religious sentiment “mountain air” and “the embalmer of the world.”

“It makes the sky and the hills sublime, and the silent song of the hills is it,” he said.

The American philosopher and pioneering psychologist William James titled one of his books The Varieties of Religious Experience and spent several hundred pages trying to get at what he called “the spiritual structure of the universe.”

Even those of us not members of any sect or creed or cult have had what Emerson or James would have described as religious experiences, whether from stumbling on a herd of elk in an Aspen forest, riding a great horse, or hearing beautiful music. But those experiences, if they are to be called religious, are expansive and liberating. They momentarily free of us from our mortal coils, and shake us out of our stale mindset. Those experiences are not tied to rigid dogmas that shrink our worlds and make us less free. They need not have a text, a church, icons, or jealous gods.

There are elements of all great religions that express humanity and kindness: be a good neighbor, show some humility, help the poor, turn the other cheek, etc. And there are those who practice those tenets, usually quietly and without trumpeting their acts for the world to see. It is sometimes expressed poetically in scripture. But the rigid, shrill Christian nationalists and the televangelists in their glittering baroque mega-churches have nothing to with any religious experience. They have nothing to with God. They worship at the altar of power.

If you subscribe to one text and one text only, and if your beliefs preclude you from having the generosity and imagination to include others who have divergent beliefs from your heavenly world here, and your picture of a heavenly afterlife, then you’re certainly no closer to God in any form than the ones you commit to hell.

There is nothing more insufferable than the arrogance and surety of those convinced of their own piety. My knowledge of the Bible—the old testament or the new one—is thin and comes from one reading. But I do remember that in the gospel of Mathew it says, “Therefore when thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may have glory of men.”

I am more than a little tired of those shrouding themselves in the righteousness of their faith, all the while violating half of the tenets about kindness, inclusion, and compassion. And I’m more than a little worried about those same high minded on their high horses wanting to inflict their religious beliefs on our democracy.

The Mayflower

The MayflowerThe wall between church and state was probably originally intended to protect minority religions from the heavy hand of government. In our mythology, those brave souls on the Mayflower suffered crossing the Atlantic in a tub of a boat to flee the persecution of King James and the Church of England. The freedom to practice the religion of your choice was revolutionary and thankfully that freedom was written into the Constitution under the First Amendment which reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;”

The First Amendment cuts both ways. It protects those wanting to practice their particular styles of religion from the government but it also theoretically protects us from a government ruled by one religion. These days, I think we need to protect that second element with rigor. For American Christian nationalists are organized, well funded, and would happily break down the wall between church and state. Should Americans be worried about a budding theocracy? In a word, amen.

Christian nationalists used to be more subtle in their efforts to have America become a “Christian nation.” But of late, they have come right out and stated their belief that we began as a Christian nation and it was our founders intent that we remain a Christian nation. Any fair reading of our history says just the opposite.

It wasn’t just Madison who opposed forming the United States as a theocratic Christian nation. George Washington expressed the same concerns. In a 1789 letter to Methodist bishops, Washington wrote, “…no one would be more zealous than myself to establish effectual barriers against the horrors of spiritual tyranny and every species of religious persecution.”

In a letter to his Irish friend Sir Edward Newenham, Washington wrote, “Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind those which are caused by a difference of sentiment in Religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing and ought most to be deprecated.”

As Randall Balmer points out in Solemn Reverence: The Separation of Church and State in American Life, John Adams, the second president, had the same instincts when he signed The Treaty of Tripoli between the United States and what is nowadays Libya. The treaty was meant to protect US merchant ships in the Mediterranean Sea from Barbary pirates and privateers. For centuries the Barbary pirates had been attacking merchant ships and once America gained independence from Britain, it lost all naval protection of its maritime trade. Article 11 of the treaty reads:

As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen (Muslims); and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan ( Mohammedan ) nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

The treaty was ratified unanimously by the Senate in 1797, without debate. Adams issued a statement affirming the treaty that read,

Now be it known, That I John Adams, President of the United States of America, having seen and considered the said Treaty do, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, accept, ratify, and confirm the same, and every clause and article thereof.

It should be clear to anyone paying attention to American politics that today’s Christian nationalists want to tear down the wall that separates church and state and create a theocracy. They may use oblique language to disguise their agenda but if you skin the first layer, there it is—almost a return to a King James style of melding church and crown. A return trip on the Mayflower.

The sentiment is captured in speeches made by fanatics such as Lt. General Michael Flynn who said in a November 2021 speech, “If we are going to have one nation under God, which we must, we have to have one religion. One nation under God and one religion under God.”

What’s called The New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) is a network of churches and ministries that calls for “spiritual warfare” across the world. Some of its adherents fault the Enlightenment for mucking up a purer view of Christianity. I’ve heard a lot of nostalgic desires for the past among conservatives but this is the first time I’ve heard of nostalgia for the dark ages. If the 1950s were too radical for you, how about a return to the medieval?

Governor Ron DeSantis

Governor Ron DeSantisNAR is more of a movement than an organization, but its call for national and world domination has millions of adherents including prominent American politicians. The goal of of the NAR movement is called “dominionism,” the idea of governing under biblical law. American politicians associated with the movement either very openly or at least in their close associations and words include Florida Governor Ronald DeSantis, former Texas governor Rick Perry, Pennsylvania governor candidate Doug Mastriano, ex-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, Colorado congresswoman Lauren Boebert…the list goes on.

Cristian Nationalists are organized, well funded, and sophisticated in their quest for power. In her masterful book, The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism, Katherine Stewart describes the many arms and long reach of those wanting to impose Christian nationalism on American Democracy. She notes that in a directive manual titled The Blitz, the strategy has three phases: 1) Introduce by law symbolic gestures like giving schools the option of having “In God we Trust” posted around the schools. Those symbolic gestures then creep into state laws requiring that “In God we Trust” be posted in schools. Such laws now exist in Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Florida, Tennessee, Mississippi, Utah, and Virginia. 2) Introduce bills that inject Christian nationalist culture into schools such as requiring Bible literacy classes and Christian Heritage week. 3) Introduce legislation that allows discrimination against those who not subscribe to Christian nationalist values—such as those who support and practice gay marriage.

The Christian nationalists have organized data bases that include nearly every American of voting age. A group called United in Purpose has files on close to 200 million Americans that include information on whether a person owns guns, hunts or fishes, likes NASCAR, or who has a “Bible lifestyle.” United in Purpose then ranks Americans based on how closely they hew to conservative values such as home schooling, church membership, and views on marriage equality. The organization targets millions of those who rank high on their criteria and do massive voter registration efforts to get them on the polls.

Samuel Perry, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, estimates that 15-20% of white Americans are hard core Christian nationalists. The good news is that younger Americans are less likely to be Christian nationalists.

But Christian nationalists do not represent all Christians; not all Christians are Christian nationalists. In fact some very distinguished Christian leaders have the same fears of this here heretic writing this here article—that Christianity is being abused by the zealous, not to bring Americans closer to God, but to bring themselves closer to power.

A group called Christians Against Christian Nationalism counts among its supporters preeminent leaders from the Baptist Church, The Episcopal Church, The United Church of Christ, The Evangelical Lutheran Church, The Presbyterian Church, and more. On the group’s website there is a statement that perfectly captures the danger. It reads in part,

Christian nationalism seeks to merge Christian and American identities, distorting both Christian faith and America’s constitutional democracy. Christian nationalism demands Christianity be privileged by the State and implies that to be a good American, one must be Christian. It often overlaps with and provides cover for white supremacy and racial subjugation. We reject this damaging political ideology and invite our Christian brothers and sisters to join us in opposing this threat to our faith and to our nation.

The men and women who sailed the Atlantic on the Mayflower in the early 17th century made a hairy crossing to an unknown wilderness to escape King James and The Church of England. They sailed to escape religious persecution. Four hundred years later, well funded organizations seek to rebuild the very thing our forebears sought to escape: a state religion. What’s more unAmerican than trying to rebuild that theocracy? These modern crusaders with their data bases, social media, billions of dollars and quest for power would take us back to the very state-sponsored religion that our forebears valiantly escaped hundreds of years ago.

As with every aberration in American politics, this one must be met with the same determination of those who truly understand how the American separation of church and state came about, why the most eminent founders wrote about it with such conviction, and why it has been defended over and over in our history.

As with every aberration in American politics, this one must be met with the same determination of those who truly understand how the American separation of church and state came about, why the most eminent founders wrote about it with such conviction, and why it has been defended over and over in our history.

We do not need our own brand of a caliphate no matter how carefully it’s cloaked in Christian scripture and vestments of khaki pants and blue blazers. We can turn to the Bible itself in Mark 12:17, which says, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Let’s not get Caesar into God’s house and let’s not have God writing statutes.

This is one battle that should enjoin freedom-loving Christians with Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Mormons, atheists and agnostics. Just as you and every American should be allowed to practice whatever religion you please or not practice at all, every American should live in a democracy free from any religious tyranny.

_______________________________________________________________________

From 3 Quarks Daily, Monday, August 29, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

(For more on this issue see “Religious Freedom” means Christian Passive-Aggressive Domination” and “How “religious freedom” became a right-wing assault on equality and the rule of law.”

October 3, 2022

The Great American Bigot

by MARK HARVEY

by MARK HARVEYThere are a number of videos circulating on the web that show angry white people screaming at Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to “Go back to where you came from!” It takes a special brand of stupid for, say, a Texan living in a town with a name like Llano located in Llano County to tell a Mexican or Mexican-American to “go back to where they came from.” For when you’re in Texas—a different spelling of the Spanish Tejas—in a county named Llano, which means plain or flat in Spanish, and in a town also named Llano for its flat ground, and you find yourself yelling at someone named Garcia or Gallegos to go home, you might be the one with the problem.

In a country with state names like Colorado, California, and New Mexico, and city names like Santa Fe, Amarillo, La Junta, and San Diego, it’s obvious that explorers, ranchers, store owners, priests, and law men had previous history in what is now Mexico. Our forebears were not just the ones who landed on the east coast after crossing the Atlantic, but also the ones who came up from south of the border, long before a border existed.

More than 200 years before the United States was even a gleam in the eye of one of our revolutionaries, Spaniards traveling up from what is now Mexico were exploring the southwest. In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado set off on a two-year exploration in search of the mythological seven cities of Cibola with hopes of bringing home gold and silver. Leaving the territory of present day Mexico, he traveled through what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and possibly Kansas. On his trip he encountered the Grand Canyon but never found the promised gold and his trip was considered a failure.

Mexico prior to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Mexico prior to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe HidalgoSanta Fe, New Mexico, was officially founded in 1610 by Don Pedro de Peralta, a governor appointed by the Spanish viceroy. The state of New Mexico was under Spanish and then Mexican control right up until 1848 and Texas was part of Mexico right up until 1836. In fact, nine states were part of Mexico right up until The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in 1848: New Mexico, Arizona, California, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, and parts of Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Obviously Latinos have scaled the heights of nearly every field from law to medicine, and from politics to professorships. Sonya Sotomayor is a shining example of a Latina who has reached the pinnacle of achievement with her appointment to the Supreme Court and her ensuing brilliance in the oral arguments and written opinions.

Scores of other Latinos have been governors, US Representatives, Senators, scholars, soldiers, scientists, artists, and entrepreneurs. Since those Latinos who have reached that level of professional achievement have a little more protection from the nativist ire, I wanted to talk about Latino laborers, the ones so often abused in our culture.

Let’s face it, there’s a lot that wouldn’t get done without the massive Latino labor force in the United States. From the vegetables you eat to the roof that keeps the rain out and most everything in between, that Latino labor force has likely had a hand—literally—in keeping you warm, fed, sheltered, and safe.

Farm worker in strawberry Field

Farm worker in strawberry FieldMore than half the hired farm workers in the United States are Hispanic. In California, which produces by far the most fruits, nuts, and vegetables of any state—close to half of what we consume—around 90% of the farmworkers are Latino. Only about 5% are white. Chances are that avocado or bunch of grapes you enjoyed was planted, picked, and packed by a Latino. And chances are that Latino doing the hard work under the hot sun is not a US citizen. The vast majority of hired farm workers are not US citizens, live far below the poverty line, and have no health insurance.

It’s one thing to live with this inherent contradiction of enjoying the fruits of low paid immigrant labor while trying to thoughtfully sort out our immigration issues, it’s quite another to go full nuclear bigot. And these last few years have produced a bumper crop of bigots in the United States.

There are few things more reprehensible than watching some lilly-lotioned, pampered politician go on and on about how immigrants from Mexico, Central America, and South America represent a class of thieving, raping, drug-running people. Evidence suggests that both legal and illegal immigrants have significantly lower crime rates than native born Americans. A paper published in 2020 by the Cato Foundation (co-founded by Charles Koch and not exactly a liberal organization) found that crime rates among illegal immigrants were 782 per 100,000, among legal immigrants 535 per 100,000, and—wait for it—1,422 per 100,000 among native born Americans.

It doesn’t take much imagination to deduce the desperation and desire for a better life that motivates people to risk it all, leave hearth and home, and cross great distances for the possibility of picking lettuce for poor wages in San Benito, California. In my experience as an employer, Latinos have a tremendous work ethic, a thriftiness, and loyalty that is simply hard to match.

On our ranch in Colorado, we have employed Mexicans, El Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Peruvians. They’ve built miles of fence in the rockiest country, cared for livestock, irrigated, operated heavy machinery and more. I suppose you’re not supposed to generalize about any group of people, but to a person they have been highly competent, loyal, non-complainers. Most are tough beyond measure.One memory I have from about five years ago illustrates this. On an early spring day when it was still snowing one of our irrigation ditches blew out. I asked the Mexican man who was already working for me if he had a friend or two for extra help in repairing the ditch. He showed up with a cousin and I noticed the cousin was wearing work clothes but his shoes were cheap loafers. I mentioned the loafers and the snow and poor footing and the fellow said they were the only shoes he had and he’d be fine. We were too far out to get him another pair of boots. I was dubious but we set out to fix the ditch. The guy worked all day in the mud and snow moving huge logs and rocks—in cheap loafers with zero traction—and didn’t gripe once.One of the great ironies of American bigots is that once upon a time, their own ancestors likely had all the same reasons for leaving Italy or Ireland or Germany or Poland. And their ancestors likely had the same pluck of today’s immigrants, bearing poor wages and abuse by earlier nativists. Italians or Irishmen came to America and were called WOPS or Paddies and suffered the indignities of those getting a foothold in a new land. Some of their great grandchildren now ferment in their smug certitude of being “true Americans.” It’s a rotten fermentation producing cheap vinegar, nothing like good wine.

Governor Ron DeSantis

Governor Ron DeSantisOne of those bigoted Italian descendants is Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who has taken his bigotry national. You’ve probably already read about his truly witless stunt shipping a group of 50 men, women, and children seeking refuge in the United States, from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts. DeSantis took $12MM from the Florida coffers to lure the refugees with false promises of jobs, legal status, and relocation to Boston. He then had them flown to Martha’s Vineyard without notifying any authorities there as a way to teach the northeastern “librulls” about the border problem. If that isn’t the definition of human trafficking and criminal fraud, I don’t know what is. Moreover, it is a heartless form of bigotry that should forever disqualify DeSantis from ever reaching his golden-ring ambition of becoming president.

As the genealogist Megan Smolenyak points out, DeSantis’s great grandmother, Luigia, immigrated from Italy to escape poverty in 1917. She had been living in Italy supported by remittances sent by her husband working the United States (sound familiar?). While crossing the Atlantic on the way to America in February of 1917, the US government passed an immigration act that barred illiterates from entering the country. Records show that Luigia was illiterate. Fortunately the act was not implemented until May, 10 weeks after her arrival to Ellis Island. Luigia slipped in by a scant few weeks. When DeSantis talks about his ancestors immigration, he acts as if it was this very orderly, patient process, when in fact his great grandmother slipped in by a few weeks. Had the timing of the 1917 immigration act been just a few days different, his great grandmother would have been one of the “undesirables” refused entry.

Nowadays, Americans need to hold two opposing thoughts in their head: 1) that most people seeking work or citizenship in the United States are doing so out of desperation, that we depend on them for essential labor, and that given the chance they can make good citizens. 2) that our immigration system doesn’t work very well and that there are lots of things that need repair.

I think that most Americans can do that. But thoughtless Americans can’t.

If the United States is to be saved from bigotry and—let’s not mince words—the celebration and embrace of stupidity, we need to embrace a certain intolerance. That is the intolerance of thoughtless nativist zealotry. This intolerance has nothing to do with elitism and in fact is in a way anti-elitist as it considers the most downtrodden among us.

In one of his letters, Abraham Lincoln put it well:

As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.’ When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty – to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

Emma Lazarus

Emma LazarusWe’re living in an unfortunate age of that “base alloy of hypocrisy” where those with the most un-American instincts and a denial of our history and demographics parade about with a fake superpatriotism. They wave giant flags hiding narrow minds and soured hearts. None of the sentiment from the words of poet Emma Lazarus, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”

Americans need to heartily reject those stupefied bigots enjoying the fresh fruit produced by poor hardworking Latinos one day, and screaming, “Go back to where you came from the next.”

From “3 Quarks Daily.” SEPT 26, 2022. Reprinted with permission.