John G. Messerly's Blog, page 20

December 7, 2022

Daniel Gray – My Good Friend

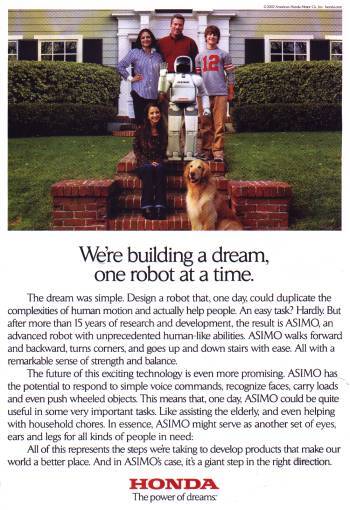

Mr. Daniel Gray, B.A. History, 2019, The University of Washington

Mr. Daniel Gray, B.A. History, 2019, The University of Washington

I spoke with my good friend Daniel Gray yesterday for about 2 hours yesterday and as usual, talking with him always makes me feel better and enriches my life. He is truly one of the finest people I’ve ever known.

I taught university philosophy at various institutions for thirty years from 1987 – 2017. In that time I had between 8,000 and 10,000 students. Of all those students—sad to say—I remember only about 25 of them really well.

And of those, there are only two with whom I still have regular contact. (This is partly due to the fact that we have moved around the country.) One is my son-in-law who took two of my classes at UT-Austin where he met my daughter. The other is a young man I met while teaching briefly at Shoreline Community College near Seattle. In the ensuing years, we have become good friends and regularly get together. (He is pictured above at his graduation from The University of Washington.)

A few years ago I wrote him a congratulatory email which he humbly described as “about the nicest thing anyone has ever written or said to me.” That may be true but it is nearly impossible not to love Daniel. He is a man of intellectual and moral virtue—possessing both a careful and conscientious mind as well as a humble and honorable soul. He is the epitome of courage. In short, he is one of the “good guys” in this world. Here is my letter:

June 14, 2019

Dear Daniel:

Congratulations! The road to your degree was much more difficult for you than for many others—just getting to class is tough for you. You should be proud.

I still remember seeing you wheel through the door of room (about) 1812 at Shoreline CC about eight years ago. You stuck out—being late, and as tall sitting as I am standing—and you had a big smile on your face. You cracked some joke shortly thereafter and I thought—I like this guy! A very clear memory. I thought I had a lot to teach Daniel, little did I know he had a lot to teach me.

Daniel, you are a world-class human being, one of the few such people I’ve ever known. Consider how many persons seek nothing but money or fame or power, while you mostly seek wisdom and truth and love.

And while I’m sure life is tough on you in ways I can’t imagine, you never whine, complain, or bemoan. You have found the Stoics’ secret to happiness—not getting what you want but wanting what you get. And this is in a world where people who have it all are constantly dissatisfied. They are rich but want to be richer, powerful but want more power, and famous but not famous enough. They are lucky enough to play golf under blue skies but then complain that the round is too slow; they buy the most expensive things but are dissatisfied with them.

Let me just say that some of the most memorable times I’ve had in the last few years have been when we motored around your neighborhood and I tried to keep up while listening to your jokes. And thanks too for listening to an old retired philosophy professor pontificate—something he really misses doing! You always let me babble on about something stupid without interruption. I’m so garrulous!

And let me also say that no matter how painful and tragic and meaningless life is, you are a shining star in all this madness. Knowing you has been a great privilege, and one of the things that have made my own life worth living. You are making what Joseph Campbell called, the hero’s journey. You are, like Dicken’s Copperfield, the hero of your own life. And you have enriched mine more than you know.

Finally let me say, Daniel, as Plato did of his beloved friend Socrates, that you are of all those I’ve known one of “the best and wisest and most just.”

with my deepest affection,

with my most fervent wishes for your future health and happiness,

I remain,

as ever,

your friend,

Dr. J

Daniel Gray – “The Seattle Socrates”

Mr. Daniel Gray, B.A. History, 2019, The University of Washington

Mr. Daniel Gray, B.A. History, 2019, The University of Washington

I spoke with my good friend Daniel Gray yesterday for about 2 hours yesterday and as usual, talking with him always makes me feel better and enriches my life. He is truly one of the finest people I’ve ever known.

I taught university philosophy at various institutions for thirty years from 1987 – 2017. In that time I had between 8,000 and 10,000 students. Of all those students—sad to say—I remember only about 25 of them really well.

And of those, there are only two with whom I still have regular contact. (This is partly due to the fact that we have moved around the country.) One is my son-in-law who took two of my classes at UT-Austin where he met my daughter. The other is a young man I met while teaching briefly at Shoreline Community College near Seattle. In the ensuing years, we have become good friends and regularly get together. (He is pictured above at his graduation from The University of Washington.)

A few years ago I wrote him a congratulatory email which he humbly described as “about the nicest thing anyone has ever written or said to me.” That may be true but it is nearly impossible not to love Daniel. He is a man of intellectual and moral virtue—possessing both a careful and conscientious mind as well as a humble and honorable soul. He is the epitome of courage. In short, he is one of the “good guys” in this world. Here is my letter:

June 14, 2019

Dear Daniel:

Congratulations! The road to your degree was much more difficult for you than for many others—just getting to class is tough for you. You should be proud.

I still remember seeing you wheel through the door of room (about) 1812 at Shoreline CC about eight years ago. You stuck out—being late, and as tall sitting as I am standing—and you had a big smile on your face. You cracked some joke shortly thereafter and I thought—I like this guy! A very clear memory. I thought I had a lot to teach Daniel, little did I know he had a lot to teach me.

Daniel, you are a world-class human being, one of the few such people I’ve ever known. Consider how many persons seek nothing but money or fame or power, while you mostly seek wisdom and truth and love.

And while I’m sure life is tough on you in ways I can’t imagine, you never whine, complain, or bemoan. You have found the Stoics’ secret to happiness—not getting what you want but wanting what you get. And this is in a world where people who have it all are constantly dissatisfied. They are rich but want to be richer, powerful but want more power, and famous but not famous enough. They are lucky enough to play golf under blue skies but then complain that the round is too slow; they buy the most expensive things but are dissatisfied with them.

Let me just say that some of the most memorable times I’ve had in the last few years have been when we motored around your neighborhood and I tried to keep up while listening to your jokes. And thanks too for listening to an old retired philosophy professor pontificate—something he really misses doing! You always let me babble on about something stupid without interruption. I’m so garrulous!

And let me also say that no matter how painful and tragic and meaningless life is, you are a shining star in all this madness. Knowing you has been a great privilege, and one of the things that have made my own life worth living. You are making what Joseph Campbell called, the hero’s journey. You are, like Dicken’s Copperfield, the hero of your own life. And you have enriched mine more than you know.

Finally let me say, Daniel, as Plato did of his beloved friend Socrates, that you are of all those I’ve known one of “the best and wisest and most just.”

with my deepest affection,

with my most fervent wishes for your future health and happiness,

I remain,

as ever,

your friend,

Dr. J

December 6, 2022

The Truth of Evolution

[image error]

“As a rule we disbelieve all the facts and theories for which we have no use.” ~ William James

A reader recently commented that there are theistic scientists who reject biological evolution, and this is why the reader also rejects the truth of evolution. As for the fact that an individual scientist rejects the near-unanimous opinion of other scientists, this is hardly surprising. There are hundreds of thousands of scientists in USA—more than ten million if you count all those employed with science and engineering degrees—so it is easy to find a few outliers. You could probably find a (very) few scientists who believe in Bigfoot or alien abductions too. But none of this changes the fact that evolution has the same scientific status as the theory of gravity or atomic theory, a claim easily verified at the National Academy of Science website or any of the hundreds of legitimate scientific websites listed below.

The consensus of belief in biological evolution is based on the overwhelming evidence from multiple sciences including physics, chemistry, biochemistry, genetics, molecular biology, cell biology, population biology, ornithology, herpetology, paleontology, geology, zoology, botany, comparative anatomy, population ecology, anthropology and more. Anyone who tells you they don’t believe in evolution is either lying or scientifically illiterate. Remember that when you get a flu shot each year or finish your antibiotics, you’re implicitly accepting evolution—viruses and bacteria evolve quickly.

Still, it is possible that the outliers are correct. Maybe what goes up doesn’t come back down, perhaps the earth is flat or things don’t change over time—perhaps the gods deceive us about all of this to test our faith. But I wouldn’t bet on it. Searching for and finding a rare outlier is simple confirmation bias—finding cases to confirm what one already believes.

Yet I have no illusions that anything I say will change people’s minds. I learned long ago that people don’t want to know, they want to believe. Interestingly, credulity itself has evolutionary origins. We are wired to believe what our parents tell us—it helped us survive—hence we often believe in adulthood what we were told when we were young.

Yet at the same time, I sometimes wonder what difference it all makes. I know that biological evolution is true beyond any reasonable doubt and those who don’t know this are mistaken. But so what? Does it really do me any good to know this? Perhaps others are happier with their false beliefs and maybe that is more important than being right. I just don’t know.

But for those interested in the truth about the fact of evolution you can visit any of these links.

Alabama Academy of ScienceAmerican Anthropological Association (1980)American Anthropological Association (2000)American Association for the Advancement of Science (1923)American Association for the Advancement of Science (1972)American Association for the Advancement of Science (1982)American Association for the Advancement of Science (2002)American Association for the Advancement of Science Commission on Science EducationAmerican Association of Physical AnthropologistsAmerican Astronomical SocietyAmerican Astronomical Society (2000)American Astronomical Society (2005)American Chemical Society (1981)American Chemical Society (2005)American Geological InstituteAmerican Geophysical Union (1981)American Geophysical Union (2003)American Institute of Biological SciencesAmerican Physical SocietyAmerican Psychological Association (1982)American Psychological Association (2007)American Society for Microbiology (2006)American Society of Biological ChemistsAmerican Society of ParasitologistsAmerican Sociological AssociationAssociation for Women GeoscientistsAssociation of Southeastern BiologistsAustralian Academy of ScienceBiophysical SocietyBotanical Society of AmericaCalifornia Academy of SciencesCommittee for the Anthropology of Science, Technology, and ComputingEcological Society of AmericaFederation of American Societies for Experimental BiologyGenetics Society of AmericaGeological Society of America (1983)Geological Society of America (2001)Geological Society of AustraliaGeorgia Academy of Science (1980)Georgia Academy of Science (1982)Georgia Academy of Science (2003)History of Science SocietyIdaho Scientists for Quality Science EducationInterAcademy PanelIowa Academy of Science (1981)Iowa Academy of Science (1986)Iowa Academy of Science (2000)Kansas Academy of ScienceKentucky Academy of ScienceKentucky Paleontological SocietyLouisiana Academy of Sciences (1982)Louisiana Academy of Sciences (2006)National Academy of Sciences (1972)National Academy of Sciences (1984)National Academy of Sciences (2007)New Mexico Academy of ScienceNew Orleans Geological SocietyNew York Academy of SciencesNorth American Benthological SocietyNorth Carolina Academy of Science (1982)North Carolina Academy of Science (1997)Ohio Academy of ScienceOhio Math and Science CoalitionPennsylvania Academy of SciencePennsylvania Council of Professional GeologistsPhilosophy of Science AssociationResearch!AmericaRoyal Astronomical Society of Canada — Ottawa CentreRoyal SocietyRoyal Society of CanadaRoyal Society of Canada, Academy of ScienceSigma Xi, Louisiana State University ChapterSociety for Amateur ScientistsSociety for Integrative and Comparative BiologySociety for NeuroscienceSociety for Organic PetrologySociety of Physics StudentsSociety of Systematic BiologistsSociety of Vertebrate Paleontology (1986)Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (1994)Southern Anthropological SocietyTallahassee Scientific SocietyTennessee Darwin CoalitionThe Paleontological SocietyVirginia Academy of ScienceWest Virginia Academy of ScienceI’m sure you could find many others … if you are really interested in the truth.

December 1, 2022

The World As It Is and The Way It Could Be

It’s cloudy and rainy in Seattle today and we had a rare dusting of snow last night. It’s a good day for reflection.

It’s cloudy and rainy in Seattle today and we had a rare dusting of snow last night. It’s a good day for reflection.I was thinking about Thomas Nagel’s notion of the absurd. For Nagel, the discrepancy between the importance we place on our lives from a subjective point of view and how insignificant they appear objectively is the essence of the absurdity of our lives. In other words, we take our lives seriously, yet from a universal perspective, they are unimaginably trivial.

But I was thinking about another incongruity—between the nature of our reality and what we imagine it could be. Our reality contains pain, suffering, anguish, poverty, hatred, loneliness, depression, violence, war, and death. Yet we can envision a world in which all of us flourish, develop our talents, partake in satisfying work and constructive leisure time, creatively cooperate, create knowledge and beauty, share in close friendships, and love without limits. As Bertrand Russell wrote in his final manuscript,

Consider for a moment what our planet is and what it might be. At present, for most, there is toil and hunger, constant danger, more hatred than love. There could be a happy world, where co-operation was more in evidence than competition, and monotonous work is done by machines, where what is lovely in nature is not destroyed to make room for hideous machines whose sole business is to kill, and where to promote joy is more respected than to produce mountains of corpses. Do not say this is impossible: it is not. It waits only for men to desire it more than the infliction of torture.

There is an artist imprisoned in each one of us. Let him loose to spread joy everywhere.

Now Russell may be mistaken—the world we envisage may not be possible. Yet, intuitively, our utopian visions do seem possible. We can imagine a heaven on earth or a transcendent future that is exponentially better than our current reality. And, if the future will be radically different than the past, then it’s at least possible it will be better.

Furthermore, our consciousness of this disparity is painful. We can build homes, so why are people homeless? We can produce food, so why are people starving? We can cooperate, so why is there so much violence? And even for those whose material needs are met, why are so many of them lonely, anxious, and depressed? Why is something amiss about life?

At first glance an easy explanation presents itself. The universe is contingent and so are we. The cosmos wasn’t created for our benefit and appears indifferent to us. And we are evolutionary accidents infused with all the leftover residue of our evolutionary history. We are both cooperative and violent, loyal to the in-group and hostile to the out-group, territorial, acquisitive, and status-seeking. Our cognitive and ethical faculties are deficient. Given our nature, it’s not surprising that life often falls short of our highest expectations.

So I would say—in a Shakespearean reference—that the problem is both in the stars and in ourselves. (“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves…”) The reality in which we find ourselves (the stars) is our home and gave birth to our consciousness, but it is not finely tuned for our flourishing despite what the religious apologists imagine. Other than our little planet the cosmos could hardly be more inhospitable.

As for ourselves, Shakespeare writes, “What a piece of work is a man, How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty, In form and moving how express and admirable, In action how like an Angel, In apprehension how like a god …” But all we need to do is look around us to know that this is no more than partly true, as Shakespeare notes,

But man, proud man,Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d;

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven,

As make the angels weep.

The only answer I see to all this is to change both the stars and ourselves. (For me this involves transhumanism—using science and technology to overcome all human limitations.1) Perhaps this will happen, perhaps not. In the meantime, we should live reveling in the beauty life offers and stoically accepting all the bad fates that will inevitably befall us. In the end, we can find comfort in living lives guided by the hope that life can be bettered.

But what if our pain becomes unbearable? What if life no longer seems worthwhile? What if the gap between what life is and what it could be is too great? Shakespeare pondered these questions in quite possibly the most famous soliloquy in all of world literature.,

To be, or not to be, that is the question:Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to sufferThe slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,Or to take arms against a sea of troublesAnd by opposing end them.________________________________________________________________________1. Transhumanism affirms the possibility and desirability of using technology to eliminate aging and overcome all other human limitations. Adopting an evolutionary perspective, transhumanists maintain that humans are in a relatively early phase of their development. They agree with humanism—that human beings matter and that reason, freedom, and tolerance make the world better—but emphasize that we can become more than human by changing ourselves. This involves employing high-tech methods to transform the species and direct our own evolution, as opposed to relying on biological evolution or low-tech methods like education and training.

If science and technology develop sufficiently, this would lead to a stage where humans would no longer be recognized as human, but better described as post-human. But why would people want to transcend human nature? Because, as the transhumanists say,

they yearn to reach intellectual heights as far above any current human genius as humans are above other primates; to be resistant to disease and impervious to aging; to have unlimited youth and vigor; to exercise control over their own desires, moods, and mental states; to be able to avoid feeling tired, hateful, or irritated about petty things; to have an increased capacity for pleasure, love, artistic appreciation, and serenity; to experience novel states of consciousness that current human brains cannot access. It seems likely that the simple fact of living an indefinitely long, healthy, active life would take anyone to posthumanity if they went on accumulating memories, skills, and intelligence.

And why would one want these experiences to last forever? Transhumanists answer that they would like to do, think, feel, experience, mature, discover, create, enjoy, and love beyond what one can do in seventy or eighty years. All of us would benefit from the wisdom and love that come with time.

The conduct of life and the wisdom of the heart are based upon time; in the last quartets of Beethoven, the last words and works of ‘old men’ like Sophocles and Russell and Shaw, we see glimpses of a maturity and substance, an experience and understanding, a grace and a humanity, that isn’t present in children or in teenagers. They attained it because they lived long; because they had time to experience and develop and reflect; time that we might all have. Imagine such individuals—a Benjamin Franklin, a Lincoln, a Newton, a Shakespeare, a Goethe, an Einstein— enriching our world not for a few decades but for centuries. Imagine a world made of such individuals. It would truly be what Arthur C. Clarke called “Childhood’s End”—the beginning of the adulthood of humanity.

(The 2 quotes above are taken from the frequently asked questions section of the Humanity+ website.)

Image Above By SounderBruce – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...\November 28, 2022

Morality and Religion

[image error]The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso in 2007

Why should I be moral? One answer is that if we are moral, the gods will reward us; and if not, the gods will punish us. This is called “the divine command theory.” (DCT) According to DCT, things are right or wrong simply because the gods command or forbid them, there is no other reason. (This is like a parent’s who says to a child: it’s right because I said so!)

To answer the question of whether morality can be based on a god we would have to know things like: 1) if there are gods; 2) if the god we believe in is good; 3) if the gods issue commands; 4) how to know the gods’ commands; 5) if we found the commands—say in a book—how would we know the commands are good ones; 6) if they were good commands how would we understand or interpret them; 7) if the came from a book which translation of the book; 8) how could you know if the translation is accurate; 9) can any translation be accurate; and 10) even if the translation was accurate how would you interpret the words you read. This is just a partial list of the problems you encounter trying to base ethics on a god or religion.

Difficulties also arise if we hear voices commanding us, or we accept an institutions’ authority. Why trust the voices or authorities? And which institution? Which revelation? Obviously, there are enormous philosophical difficulties with basing ethics on religion.

But let’s say that there are gods, that you have found the right one, that the right one issued commands, that the commands are good, that you have access to the right commands (because you found the right book, church, or had the right vision), that you understand the commands, that you interpret the commands correctly even though they came from a book that has been translated from one language to another over thousands of years? (Anyone who has ever translated knows that you can’t translate word for word between languages.) But let’s just say that somehow you are right about everything. Can you then base ethics on religion?

More than 2,000 years ago Plato answered this question in the negative. In Plato’s dialogue Euthyphro, Socrates asked a famous question: “Are things right because the gods command them, or do they command them because they are right?” If things are right simply because the gods command them, then their commands are arbitrary—without reason. There are no good reasons for their commands. The gods then are like petty tyrants who just command things because they have the power.

On the other hand, if the gods command things because they are right, then there are reasons for their commands. The gods command things because they see or recognize that certain commands are really good for us. But if that is the case, then there is some standard or norm or criteria by which good or bad is to be measured. And this standard is independent of the gods.

So either the god’s commands are without reason, and therefore arbitrary, or they are with reason, and thus are commanded according to some standard. This standard—say that we would all be better off—is thus the reason we should be moral. And that reason, not a god’s authority—is what makes something right or wrong. And the same is true for an authoritative book. Something is not wrong simply because the book says so. There must be a reason for this and if there is not, then the book is simply wrong.

Of course one could argue that even if the gods are petty tyrants who command us without reason—other than their own amusement—we should still follow the commands so as not to suffer—since the gods are possibly powerful and mean enough to do so. If they can inflict eternal torture—if they are the ultimate sadists—then we do have a reason to follow their commands—to avoid torture!

The response to this is that we don’t know that the gods will reward us for following their non-rational commands. Maybe the gods reward people who use their reason and don’t accept such commands and punish those who are so frightened as to accept non-rational commands. This seems to make some sense if the gods are petty, tyrannical bullies, they might like it if you stood up to them. Who knows?

The foregoing discussion should suffice to show how difficult it is to base ethics on religion. Again, even if one could overcome all the practical difficulties involved in philosophically justifying religion, it seems that either a) the god’s commands are arbitrary and there is thus no reason to follow them; or b) the god’s commands are not arbitrary and there are reasons for them. But if the latter is the case, then we are doing philosophical, not theological, ethics. We are looking for the reasons why things are moral or immoral.

Finally, you might object that the gods have reasons for their commands, and we just can’t know them. But if this is the case, if we really can’t know anything about the gods’ reasons, if the ways of the gods “are mysterious to humans,” then what’s the point of religion? If you can’t know anything why the gods command things, then why follow their commands, why have religion at all, why listen to the preacher? If it’s all a mystery, then no person or book or church has anything coherent to say about God, ethics, or anything else. and in that case, you should just be a skeptic.

If we want to rationally justify morality, then we will have to do it in a moral theory independent of hypothetical gods. We will have to engage in philosophical ethics.

November 22, 2022

The Future of Robots

The computer scientist Marshall Brain penned these prescient thoughts on robotics and the future of the economy about twenty years ago in three essays and a FAQ section on his website. Because of their importance and insight, I wanted to summarize them for my readers, staying close to the original texts with little commentary.

Robotic Nation

Overall Summary

The Tip of the Iceberg – We now see technology’s impact on employment because of

Moore’s Law – Exponential growth is leading to a

The New Employment Landscape – where the equation

Labor = Money – will no longer hold, necessitating new economic models.

The tip of the Iceberg – Brain believes every fast food meal will be (almost) fully automated within a few years, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. Right now we interact with automated systems: ATM machines, gas pumps, self-serve checkout, etc. These systems lower costs and prices, but “these systems will also eliminate jobs in massive numbers.” There will be massive unemployment in the next decades as we enter the robotic revolution.

A feasible scenario suggests that in the next fifteen years most retail transactions will be automated and 5 million retail jobs lost. Next, walking, human-shaped robots will begin to appear–Honda’s Asimo is an early example. By 2025 we may have machines that hear, move, see, and manipulate objects with roughly the ability of humans. These machines will be equipped with AI systems, making them seem human-like. Robots will get cheaper and become more human-shaped to easily facilitate their use of cars, elevators, and other objects in the human environment. By 2030 you will buy a $10,000 robot that will clean, vacuum, mop, sweep, mow grass, etc. These robots would last for years, need no vacation or sick time, and eliminate human jobs. Robotic fast food places will open shortly thereafter and by 2040 will be completely robotic. By 2055 robots will replace half the American workforce leaving millions unemployed. Restaurants, construction, airports, hospitals, malls, amusement parks, truck drivers, and airplane pilots are just some of the jobs and locations that will have mostly robotic workers.

While robotic vision or image processing is currently a stumbling block, Brain thinks we will make significant progress in this field in the next twenty years. This single improvement will yield catastrophic changes, just as the Wright brother’s breakthrough brought about aviation. Brain applauds these developments. After all, who wants to clean toilets, flip burgers, and drive trucks? “These activities represent a massive waste of human potential.”

If all this sounds crazy, Brain asks you to consider a prediction of faster than sound aircraft in 1900; a time when there were no radios, model T’s, or airplanes. Then many thought heavier than air flight was impossible, and one who predicted it was often ridiculed. Such considerations lead to the conclusion that the employment world will change dramatically over the next fifty years. Why? The fundamental answer is Moore’s Law, that CPU power doubles every 18 to 24 months. Computers in 2020 will have the power of the NEC Earth Simulator. By 2100 we may have the power of a million human brains on our desktop. Robots will take your job by 2050 with the marriage of a cheap computer with the power of a human brain; a robotic chassis like Asimo; a fuel cell; and advanced software.

While the employment landscape is not so different from the one of 100 years ago, it will be vastly different once robots that see, hear, and understand language compete with humans for jobs. The 50 million jobs in fast food, delivery, retail, hotels, restaurants, airports, factories, construction will be lost in the next fifty years. But America can’t deal with 50 million unemployed. And the economy will not create 50 million new jobs. Why?

In the current economy, people trade labor for money. But without enough work people won’t’ be able to earn money. What then? Brain thinks we might erect housing for the unemployed since you can’t live without a job, and we need to have a guaranteed income. But whatever we do, we had better start thinking about the kind of societal structures needed in a “robotic nation.”

Robots in 2015

Overall Summary

We Will Replace all the Pilots – and then

Robots in Retail – but we won’t

Create New Jobs – which means there will be

A Race to the Bottom – so

Where Do We Want to Go?

If you went back to 1950 you would find people doing most of the work just like they do in 2000. (Except for ATM machines, robots on the auto assembly line, automated voice answering systems, etc.) But we are on the edge of the robotic nation and half the jobs will be automated in the near future. Robots will be popular because they save money. For example, if an airline replaces expensive pilots, the money saved will give them a competitive advantage over other airlines. We’ll feel sorry for the pilots at first but forget about them when the savings are passed on to us. Next will be the retail jobs and then others will follow. What about new job creation? After all, the model T created an automotive industry. Won’t the robotic industry do the same? No. Robots will assemble robots and engineering and sales jobs will go to those willing to work for less.

The robotic nation will have lots of jobs—for robots! Our economy does not create many high-paying jobs. (And for those there is intense competition.) Instead, there is a “race to the bottom.” A race to pay lower wages and benefits to workers and, if technologically feasible, to eliminate them altogether. Robots will make the minimum wage—which has declined in real dollars for the last forty years—irrelevant; there will be no high-paying jobs to replace the lost low-paying ones. So where do we want to go? We are on the brink of massive unemployment unknown in American history, and everyone will suffer because of it. We need to answer a fundamental question: How do we want the robotic economy to work for the citizens of this nation?

Robotic Freedom

Overall Summary

The Concentration of Wealth – is accelerating bringing about

A Question of Freedom – why not let us be free to create

Harry Potter and the Economy – which leads us to

Stating the Goals – increase human freedom by weaning away from unfulfilling labor by

Capitalism Supersized – economic system that provides for all people which has

The Advantages of Economic Security – better for everyone because

You, Personally, and the Robots – because even your job is vulnerable.

We are on the leading edge of a robotic revolution that is beginning with automated checkout lanes; the pace of this change will accelerate in our lifetimes. Furthermore, the economy will not absorb all these unemployed. So what can we do to adapt to the catastrophic changes that the robotic nation will bring?

People are crucial to the economy. But increasingly there is a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few–the rich make more money and the workers make less. With the arrival of robots, all the income of corporations will go to the shareholders and executives. But this automation of labor—robots will do almost all the work 100 years from now—should allow people to be more creative than ever. Can we design the economy to do this? Why not design an economy where we abandon the “work or don’t eat” philosophy?

This is a question of freedom. Consider J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books. Amazingly she wrote them while on welfare and would not have done so without public support. Think how much human potential we lose because people have to work to eat. How much music, art, science, literature, and technology have never been created because people had to work. Consider that Linux, one of the world’s best-operating systems, was created by people in their spare time. Why not create an economic model that encourages this kind of productivity? Why not create an economic model where we don’t have to hope the aged die before they collect too much social security, where we don’t have so many working poor, or people sleeping in the streets? Brain says “we are entering an historic era that has the potential to completely change the human condition.”

Brain argues that we shouldn’t ban robots because that leads to economic stagnation and lots of toilet cleaning. Instead, he states the goals: raise the minimum wage; reduce the workweek; and increase welfare systems to deal with unemployment. What is needed is a complete re-thinking of economic goals. The primary goal of the economy should be to increase human freedom. We can do this by using robotic workers to free people to: choose the products; start the businesses, creative projects; and use their free time as they see fit. We need not be slaves to the sixty-hour work week “the antithesis of freedom.”

The remainder of the article offers specific suggestions (supersize capitalism, guaranteed economic security) of how we would fund a society in which persons actualize their potential to create art, literature, science, music, etc. without the burden of wage slavery. The advantages of such a system would be significant. (If all this seems fanciful, consider how fanciful our world would be to the slaves and serfs that most humans have been throughout history.) Brain says we are all vulnerable to the coming robotic nation. Let us then rethink our world, and welcome the robotic workers who will give us the time and the freedom we all so desperately desire.

“Robotic Nation FAQ”

Question 1 – Why did you write these articles? What is your goal? Answer – Robots will take over half the jobs by 2030 and this will have disastrous consequences for rich and poor alike. No one wants this. I’d like to plan ahead.

Question 2 – You are suggesting that the switchover to robots will happen quickly, over the course of just 20 to 30 years. Why do you think it will happen so fast? Answer – Consider the analogy to the auto or computer revolutions. Once things get going, they proceed rapidly. Vision, CPU power, and memory are currently holding robots back—this will change. Robots will work better and faster than humans by 2030-2040.

Question 3 – In the past technological innovation created more jobs, not less. When horse-drawn plows were replaced by the tractor, security guards by the burglar alarm, craftsmen making things by factories making them, human calculators by computers, etc., it improved productivity and increased everyone’s standard of living. Why do you think that robots will create massive unemployment and other economic problems? Answer – First, no previous technology replaced 50% of the labor pool. Second, robotics won’t create new jobs. The work created by robots will be done by robots. Third, we are creating a second intelligent species that competes with humans for jobs. As this new species gets better, it will do more of our work. Fourth, past increases in productivity meant more pay and less work but today worker wages are stagnant. Now productivity gains result in the concentration of wealth. This may work itself out in the long run, but in the short run, it is devastating.

Question 4 – There is no evidence for what you are saying, no economic foundation for your proposals. Answer – Just Google ‘jobless recovery,’” for the evidence. Automation fuels production increases but does not create new jobs.

Question 5 – What you are describing is socialism. Why are you a socialist/communist? Answer – I am a capitalist who has started three successful businesses and written a dozen books. “I am all for free markets, innovation and investment.” Socialism is the view that producing and distributing goods is done collectively by centralized governmental planning. He argues that individuals should own the means of producing and be free “to earn whatever they can with their products, services, and innovations.” By giving consumers a share of the wealth–which they won’t be able to earn with work–we will “enhance capitalism by creating a large, consistent river of consumer spending. It is also a way of providing economic security to every citizen…” Communism is usually identified by the loss of freedom and choice, whereas he wants people to have “economic freedom for the first time in human history…”

Question 6 – Why do you believe that a $25,000 per year stipend for every citizen is the solution to the problem? Answer – With robots doing all the work, we will finally have an opportunity to do this, which is better for everyone.

Question 7 – Won’t your proposals cause inflation? Answer – Tax rebates, similar to his proposals, don’t cause inflation. Neither do taxes, social security, or other programs that re-distribute wealth.

Question 7a – OK, maybe it won’t cause inflation. But there is no way to give everyone $25,000 per year. The GDP is only $10 trillion. Answer – Brain argues that we should do this gradually. Remember $150 billion, about what the US spent on the Iraq war in 2003, is $500 for every man, woman, and child in the US. It isn’t that much in our economy. At the moment our government collects about $20,000 per household in taxes each year and so “it is very easy to imagine a system that pays US citizens $25,000 per year.”

Question 7b – Is $25,000 enough? Why not more? Answer – “As the economy grows, so should the stipend.”

Question 8 – Won’t robots bring dramatically lower prices? Everyone will be able to buy more stuff at lower prices. Answer – True. But current trends show that most of the wealth will end up in the hands of a few. Also, if you have no wealth it won’t matter that prices are lower. To let every citizen benefit from the robotic nation distribute the wealth to all.

Question 9 – Won’t a $25,000 per Year Stipend Create a Nation of Alcoholics? Answer – Brain notes this is a common question since many people assume that if we aren’t forced to do hard labor we’ll just do nothing or drink all day. He says he has no idea where this fear comes from (probably from political, philosophical, moral, and religious ideas promulgated by certain groups.) He dispels the idea with examples: a) he supports his wife who works at home; b) his in-laws are retired and live on a pension and social security; c) he has independently wealthy friends; d) he knows students supported by loans; and e) many are given free education and training. None of these people are lazy or alcoholics! (Perhaps it’s the reverse, with no possible source of income people give up.)

Question 9a – Yes, stay-at-home moms and retirees are not alcoholic parasites, but they are exceptions. They also are not productive members of the economy. Society will collapse if we do what you are talking about. Answer – Everyone participates in the economy by spending money. Unless there are people with money there’s no economy. The cycle of getting paid by a paycheck and spending it at businesses that get the money from customers is just that–a cycle—which will stop if people have no money. And giving a stipend won’t stop people from trying to make more money, create, invent or play. Some people will become alcoholics though, just as they do now, but Brain thinks we’ll have fewer lazy alcoholics “if we give them enough money to live decent, dignified lives…”

Question 10 – Why not let capitalism run itself? We should eliminate the minimum wage, welfare, child labor laws, the 40-hour workweek, antitrust laws, etc. Answer – “…because of the power of economic coercion.” This economic power is why companies pay wages of a few dollars a week in most parts of the world. “We, The People, should enact the stipend to give ourselves true economic independence.”

Question 11 – Why didn’t you include the whole world in your proposals–why are you U.S.-centric? Answer – Ideally, the global economy would adopt these proposals.

Question 12 – I love this idea. How are we going to make it happen? Answer – We should spread the word.

Thank you Marshall Brain for such an uplifting vision.

1. The articles in their entirety can be found here.

November 18, 2022

Piaget: Philosophical Illusions

[image error]

Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980) was one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth century and a scholar of philosophy, psychology, and biology.In the mid-twentieth century, Piaget penned the book, Insights and Illusions of Philosophy, which offers a critique of philosophy that is uninformed by science. Piaget has been accused of scientism, but his critique of philosophy is worth considering.

[image error][image error]

Piaget’s lifelong interest—the reason he devoted decades to studying the intellectual development of children—was in articulating a biological epistemology. Piaget’s early intellectual experiences with Bergson and Spencer left him convinced that speculation uninformed by science was intellectually dishonest. (This reminds me of Bertrand Russell saying: “A philosopher who uses his professional competence for anything other except a disinterested search for truth is guilty of a kind of treachery.”) Speculation, based on intuition and introspection, has no epistemological justification regarding empirical facts. Needless to say, he saw philosophical speculation as a hallmark of philosophy and he clearly expressed his disdain for it:

It was while teaching philosophy that I saw how easily one can say … what one wants to say … In fact, I became particularly aware of the dangers of speculation … It’s a natural tendency. It’s so much easier than digging out facts. You sit in your office and build a system. It’s wonderful. But with my training in biology, I felt this kind of undertaking was precarious.”1

Philosophical speculation can raise questions, but it cannot provide answers; answers are found only in testing and experimentation. Knowledge presupposes verification, and verification attains only by mutually agreed-upon controls. Unfortunately, philosophers do not usually have experience in inductive and experimental verification.

Young philosophers because they are made to specialize immediately on entering the university in a discipline which the greatest thinkers in the history of philosophy have entered only after years of scientific investigations, believe they have immediate access to the highest regions of knowledge, when neither they nor sometimes their teachers have the least experience of what it is to acquire and verify a specific piece of knowledge.2

But how did it happen that philosophy, which gave birth to the sciences, became so separate from the scientific method? Piaget traces this separation to the 19th century when philosophy came to believe that it possessed a “suprascientific” knowledge. This split was disastrous for philosophy, as it retreated into its own world, lost its hold on the intellectual imagination, and had its credibility questioned. For Piaget, philosophy is synonymous with science or reflection upon science, and philosophy uninformed by science cannot find truth; at most it provides subjective wisdom. Philosophy, Piaget concludes, is not even about truth; at most it is about meaning and values.

________________________________________________________________________

1. Jean-Claude Bringuier, Conversations with Piaget (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 13.

2. Jean Piaget, Insights and Illusions of Philosophy, trans. W. Mays (New York: World Publishing Company, 1971) xiv.

November 14, 2022

Learning to Die in the Anthropocene

Roy Scranton served as a private in the US Army from 2002 to 2006, including a term in Iraq. In his recent book, Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization, he reflects on one of the greatest threats to humanity—climate change. Scranton argues that, as we destroy the climate that sustains us, we destroy ourselves. We are our own worst enemy.

Humans have thrived in a climate that has been stable for more than a half-million years, but the burning of fossil fuels will end that interval. Our fate follows from our shortcomings. “The problem with our response to climate change isn’t a problem with passing the right laws or finding the right price for carbon or changing people’s minds or raising awareness … The problem … is us.”

And our capitalist system exacerbates the problem, as profits drive the exploitation of the earth’s resources. Our biological nature and our social, economic, and political systems have brought us to the precipice. Scranton holds out little hope that things might change. The story of human civilization, in the end, will likely be a tragedy.

What then should we do? Scranton tells us that we should probably accept the end of civilization and learn how to die. If practicing philosophy is learning how to die, as so many philosophers have said, then we live in the quintessential philosophical age. We should come to terms with the end of civilization.

But this is hard to do. We rebel at the idea that we are doomed, and like many previous civilizations, we continue to march headlong toward disaster. We dismiss the idea that the end is just around the corner, telling ourselves we’ll be fine. We destroy the seas and atmosphere that support us, we kill off other species and pump greenhouse gases into the air. Surely riding bikes and being vegetarians is too high a price to pay to save civilization!

Yes, we should try to preserve the best of human civilization. But the thoughtful, living in the Anthropocene, accept that we will all probably die. While this may be a depressing thought, only honest reflection on it gives us any chance of saving ourselves.

As for me, I believe we will all die unless we use future technologies to enhance our moral and intellectual faculties. We must evolve or we will all die.

November 9, 2022

Once-Born and Twice-Born People

[image error]

William James, in his famous book The Varieties of Religious Experience, drew a contrast between what he calls “once-born” and the “twice-born” people. Once-born people appear biologically predisposed to happiness. They are relatively untroubled by their own setbacks as well as by the suffering the world; they rarely speak ill of others; they don’t complain much; they tend not to be fearful or angry. Today we might call them happy-go-lucky, easy-going, or upbeat.

By contrast, twice-borns feel there is something wrong with reality that must be rectified. They have a pessimistic view of the world; they experience more ups and downs in life; they wish the world could be different from it is. Today we might call them neurotic, anxious, or unstable. James describes them like this:

There are persons whose existence is little more than a series of zigzags, as now one tendency and now another gets the upper hand. Their spirit wars with their flesh, they wish for incompatibles, wayward impulses interrupt their most deliberate plans, and their lives are one long drama of repentance and of effort to repair misdemeanors and mistakes. (p.169)

However, this doesn’t mean that twice borns are unhappy. The reason is that their attitude often leads to a crisis, experienced as clinical depression, in a desire to understand the meaning of life. But the incompatibility of their desire for making sense of things and their pessimism demands a resolution if they are to love life again. And it is this demand that can lead to rebirth. As an example, James considers the crisis of meaning experienced by Leo Tolstoy. (I have written about his crisis here.) James describes Tolstoy’s transformation like this: “The process is one of redemption, not of mere reversion to natural health, and the sufferer, when saved, is saved by what seems to him a second birth, a deeper kind of conscious being than he could enjoy before. ” (p.157)

While the sense of being “born again” often describes so-called religious or mystical experiences, James uses the term to describe any experience where there is a strong sense of renewal after a tragic event. The point is that challenges and tragedies can be seen as a means to a happier and more meaningful life.

As for the happy life, James said it consists of four main ingredients. First, we must choose to view the world as positive even though life contains sorrow and pain. Second, we must take risks by acting from the demands of our hearts. Third, we must act as if we are free and life is meaningful even though we can’t be sure of either. Finally, we should remember that a crisis of meaning often leads to the happiest life. Thus a crisis for twice borns presents the possibility of renewal.

________________________________________________________________________

Postscript – William James knew a lot about all this, as he suffered from depression for much of his life. (A number of other people of historic importance suffered from depression as well including Abraham Lincoln, Sigmund Freud, Georgia O’Keeffe, Franz Kafka, and the Buddha.)

I think there is a lot to this. Given our reality, we should try to learn from suffering. Viktor Frankl wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning that enduring suffering nobly was one way to find meaning in life. Perhaps we must endure a sort of purgatory in order to experience true happiness. On the other hand, I don’t believe that twice-borns necessarily become depressed. Maybe they find joy in a philosophical search for meaning instead.

Still, I don’t believe that pain and suffering are intrinsically good no matter what good outcome they might lead to. Like my colleague David Pierce, who first articulated the hedonistic imperative, I too believe that all pain and suffering in life should be eliminated. The meaning of life is to create a heaven on earth.

As for the contrary view, that suffering is somehow necessary for redemption, it was best captured in these lines by Shelley from his “Ode To A Skylark,”

We look before and after,And pine for what is not:Our sincerest laughterWith some pain is fraught;Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Yet if we could scorn

Hate, and pride, and fear;

If we were things born

Not to shed a tear,

I know not how thy joy we ever should come near.

(I’m not saying I agree with this sentiment, but Shelley sure had control of language.)

___________________________________________________________________________

Quotes are from William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (London: Penguin Books, 1902, 1982)

(This entry borrows from this article on the website The Pursuit of Happiness.)

November 6, 2022

Richard Taylor “Meaning of Life”

Richard Taylor (1919 – 2003) was an American philosopher renowned for his controversial positions and contributions to metaphysics. He advocated views as various as free love and fatalism and was also an internationally known beekeeper. He taught at Brown, Columbia, and the University of Rochester, and had visiting appointments at about a dozen other institutions. His best-known book is Metaphysics.

In the concluding chapter of his 1967 book, Good and Evil (Great Minds Series), Taylor suggests that we examine the notion of a meaningless existence so that we can contrast it with a meaningful one. He takes Camus’ image of Sisyphus‘ eternal, pointless toil as archetypical of meaninglessness. Taylor notes that it is not the weight of the rock or the repetitiveness of the work that makes Sisyphus’ task unbearable, it is rather its pointlessness. The same pointlessness may be captured by other stories—say by digging ditches and then filling them in forever. Crucial to all these stories is that nothing ever comes of such labor.

But now suppose that Sisyphus’ work slowly built a great temple on his mountaintop: “then the aspect of meaninglessness would disappear.” In this case his labors have a point, they have meaning. Taylor further argues that the subjective meaninglessness of Sisyphus’ activity would be eliminated were the Gods to have placed within him “a compulsive impulse to roll stones.” Implanted with such desires, the gods provide him the arena in which to fulfill them. While we may still view Sisyphus’ toil as meaningless from the outside—for externally the situation has not changed—we can now see that fulfilling this impulse would be satisfying to Sisyphus from the inside. For now, he is doing exactly what he wants to do—forever.

Taylor now asks: is life endlessly pointless or not? To answer this question he considers the existence of non-human animals—endless cycles of eating and being eaten, fish swimming upstream only to die and have offspring repeat the process, birds flying halfway around the globe only to return and have others do likewise. He concludes that these lives are paradigms of meaninglessness.

That humans are part of this vast machine is equally obvious. As opposed to non-human animals we may choose our goals, achieve them, and take pride in those achievements. But even if we achieve our goals, they are transitory and soon replaced by others. If we disengage ourselves from the prejudice we have toward our individual concerns, we will see our lives to be like Sisyphus’. If we consider the toil of our lives we will find that we work to survive, and in turn, pass this burden on to our children. The only difference between us and Sisyphus is that we leave it to our children to push the stone back up the hill.

And even were we to erect monuments to our activities, they too would turn slowly turn to dust. That is why, coming upon a decaying home, we are filled with melancholy:

There was the hearth, where a family once talked, sang, and made plans; there were the rooms, here people loved, and babes were born to a rejoicing mother; there are the musty remains of a sofa, infested with bugs, once bought at a dear price to enhance an ever-growing comfort, beauty, and warmth. Every small piece of junk fills the mind with what once, not long ago, was utterly real, with children’s voices, plans made, and enterprises embarked upon.

When we ask what it all was for, the only answer is that others will share the same fate, it will all be endlessly repeated. The myth of Sisyphus’ then exemplifies our fate, and this recognition inclines humans to deny their fate—to invent religions and philosophies designed to provide comfort in the face of this onslaught.

But might human life still have meaning despite its apparent pointlessness? Consider again how Sisyphus’ life might have meaning; again if he were to erect a temple through his labors. Notice not only that the temple would eventually turn to dust, but that upon completion of his project he would be faced with boredom. Whereas before his toil had been his curse, now its absence would be just as hellish. Sisyphus would now be “contemplating what he has already wrought and can no longer add anything to, and contemplating it for an eternity!”

Given this conclusion, that even erecting a temple would not give Sisyphus meaning, Taylor returns to his previous thought—suppose that Sisyphus was imbued with a desire to labor in precisely this way? In that case, his life would have meaning because of his deep and abiding interest in what he was doing. Similarly, since we have such desires within us, we should not be bored with our lives if we are doing precisely what we have an inner compulsion to do: “This is the nearest we may hope to get to heaven…”

To support the idea that meaning is found in this engagement of our will in what we are doing, Taylor claims that if those from past civilizations or the past inhabitants of the home he previously described were to come back and see that what was once so important to them had turned to ruin, they would not be dismayed. Instead, they would remember that their hearts were involved in those labors when they were engaged in them. “There is no more need of them [questions about life’s meaning] now—the day was sufficient to itself, and so was the life.” We must look at all life like this, its justification and meaning come from persons doing what “it is their will to pursue.” This can be seen in a human from the moment of birth, in its will to live. For humans “the point of [their] living, is simply to be living…” Surely the castles that humans build will decay, but it would not be heavenly to escape from all this, that would be boredom: “What counts is that one should be able to begin a new task, a new castle, a new bubble. It counts only because it is there to be done and [one] has the will to do it.”

Philosophers who look at the repetitiveness of our lives and fall into despair fail to realize that we may be endowed, from the inside, with the desire to do our work. Thus: “The meaning of life is from within us, it is not bestowed from without, and it far exceeds in both beauty and permanence any heaven of which men have ever dreamed or yearned for.”

Summary – We give meaning to our lives by the active engagement our will has in our projects.

______________________________________________________________________

Richard Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 136.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 136.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 139.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 140.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 141.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 141.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 141.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 141.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 142.

Taylor, “The Meaning of Life,” 142.