John G. Messerly's Blog, page 17

April 20, 2023

Dylan Thomas: Rage Or Resignation?

Occasionally, an interesting comment on one of my blog piques my interest; here is an excerpt from a recent one:

“The “lostness concerning our place in an indifferent cosmos” as you put it … seems to be a pervasive thought process even among the laymen when presented with the idea of an overall lack of meaning, but why is that? I tend more to agree with guys like Simon Critchley in that meaningless is awesome! Yeah, the cosmos is indifferent! All that means is that we have been granted access to this amazing, possibly infinite sandbox to play in for as long as we allow ourselves to do so! Maybe that’s just me.”

I wish I could embrace the possible meaninglessness of life the way Critchley does. He eschews all narratives of salvation and is edified by the ordinary things around him which, on closer inspection, are really extraordinary. Perhaps this is what Kazantzakis had in mind when he called hope “the last temptation.” Rather than hope for unattainable salvation, we should find meaning in the sights, sounds, and loves that surround us. This was Zorba the Greek’s solution in Kazantzakis’s novel. You find a similar idea in Stoicism. If we could be resigned and indifferent to our fate, while doing our duty at the same time, we would experience equanimity of mind. This might be the best we can do.

But then again, to quote the commentator, “maybe it’s just me” but this doesn’t seem to be enough. This raises a question. Is there something wrong with me because I cannot find the extraordinary within the ordinary, I cannot accept my fate and my finitude; or is something wrong with the world, that it appears not to give me the infinite being, consciousness, and bliss I so desire? Shakespeare said that the problem wasn’t in the stars but in ourselves, but I think the problem is in both. To be truly content we must change both ourselves and the world.

Yet it is a big project to change the world. For now, we may be forced to accept our fate and find solace in doing so. Perhaps this is the best we can do. Just let it go—resignation, acceptance, peace. The nirvana of nothingness. But as soon as I say such things another voice within me objects. I hear Dylan Thomas.

“Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

April 16, 2023

Jacques Monod: “Chance and Necessity”

[image error]

Jacques Monod (1910 – 1976) was a French biologist who was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965 for his discoveries in molecular biology. His classic book Chance and Necessity: Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology[image error] is an antipode to Teilhard’s The Phenomena of Man, as well as other versions of progressivism.

According to Monod, our early ancestors did not feel themselves strangers in the world amongst plants that grew and died, and animals that ate, fought, protected their young, and died. Instead, they saw things like themselves whose purpose was to survive and produce progeny. They also saw rivers, mountains, oceans, lighting, rain, and stars in the sky, assuming no doubt that these objects had purposes too. If humans have purposes, nature must too—and with that single thought animism was born, nature and humans were connected.

However, modern science largely severed this connection, whereas Teilhard tried to revive it, placing him squarely in the company of thinkers trying to restore the connection between human and nature’s purposes. Hegel’s grand system, Spencer’s evolutionism, and Marx and Engels’ dialectical materialism all insert meaning and purpose into purposeless evolution. The cost though is abandoning objectivity, for chance is the source of innovation in biology. In Monod’s famous words:

Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, at the very root of the stupendous edifice of evolution: this central concept of modern biology is no longer one among other possible or even conceivable hypothesis. It is today the sole hypothesis, the only one that squares with observed and tested fact. And nothing warrants the supposition—or the hope—that on this score our position is likely ever to be revised.[i]

For Monod chance destroys both teleology and anthropocentrism. Errors in the replication of the genetic messages—genetic mutations—are essentially random. The process is explicitly non-teleological—they are not goal-seeking processes initiated and controlled by rational entities. (Still, Monod does invoke the softer term teleonomy—goal-oriented structures and functions that derive from evolutionary history without guiding foresight.) As for anthropocentrism, we were not destined to be, we are accidents. “The universe was not pregnant with life nor the biosphere with man. Our number came up in the Monte Carlo game. Is it any wonder if, like the person who has just made a million at the casino, we feel strange and a little unreal?”[ii]We are neither the goal nor the center of creation.

So we seem lost, but we didn’t always feel this way. For eons of time, humans survived in groups with the cohesive social structures necessary for survival, leading to the acceptance of tribal laws and the mythological explanations that gave them sovereignty. From such people,

…we have probably inherited our need for an explanation, the profound disquiet which goads us to search out the meaning of existence. That same disquiet has created all the myths, all the religions, all the philosophies, and science itself. That this imperious need develops spontaneously, that it is inborn, inscribed somewhere in the genetic code, strikes me as beyond doubt.[iii]

Human social institutions have both a cultural and biological basis, with religious phenomena invariably at the base of social structures to assuage human anxiety with narratives, stories, and histories of past events. Given our innate need for explanation, the absence of one begets existential angst, alleviated only by assigning humans a proper place in a soothing story of a meaningful cosmos. But just a few hundred years ago science offered a new model of objective knowledge as the sole source of truth.

It wrote an end to the ancient covenant between man and nature, leaving nothing in place of the precious bond but an anxious quest in a frozen universe of solitude. With nothing to recommend it but a certain puritan arrogance, how could such an idea win acceptance? It did not; it still has not. It has however commanded recognition; but that is because, solely because, of its prodigious power of performance.[iv]

Science undermines the ancient stories as well as the values that were derived from them, leaving us with an ethic of knowledge. Unlike animistic ethics, which claim knowledge of innate, natural, or religious law, an ethics of knowledge is self-imposed. An ethic of knowledge created the modern world—through its technological applications—and it is the only thing that can save the world. Our knowledge has banished cosmic meaning, yet it might also be our redemption. He concludes: “The ancient covenant is in pieces; man knows at last that he is alone in the universe’s unfeeling immensity, out of which he emerged only by chance. His destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty. The kingdom above or the darkness below: it is for him to choose.”[v]

Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology [image error]

[i] Jacques Monod, Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology (New York: Vintage, 1972), 112.

[ii] Monod, Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology, 145.

[iii] Monod, Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology, 167.

[iv] Monod, Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology, 169.

[v] Monod, Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology, 180.

April 10, 2023

Truth & Lying

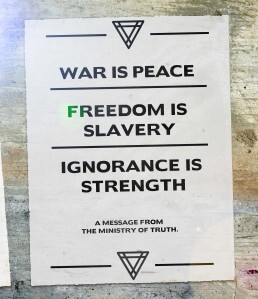

THE LAYERS THAT HIDE REALITY

Growing up requires constantly revising our previous understanding of the world. This process begins as infants pass through various stages of cognitive and emotional development, each stage bringing the child closer to truths about the world. In the beginning, an understanding of object permanence, time, and causation, are gained. Slowly the biological impediments to understanding are being overcome. Then, as we mature, we confront a mysterious social world. There, unlike in the world of childhood books, animals and people aren’t always our friends, school and sports make demands upon us, and social groups accept or ostracize us. The cocoon of childhood slowly vanishes, as the layers of film hiding reality disappear.

As we reach late adolescence becoming educated involves acknowledging the social, historical, biological, and psychological layers that blanket reality. We discover that religion, politics, ethics, and relationships are not as they first appear. Their reality, at least to the extent we have access to them, has been buried beneath layers of falsehoods. For example, we may have been taught that religion and country are good only to find them bastions of hypocrisy and corruption; or we may have believed that some persons were trustworthy friends only to find that they were not. Such experiences bring home the difference between appearance and reality. But why the gap between our youthful idealistic views and the reality of the world? Is it that our truth-detection methods become more sophisticated as we mature thereby allowing us to see things more clearly, or have we been lied to all our young lives about the truth? Surely part of the answer is that we have been lied to, but why?

IGNORANCE, NOBLE LIES, IGNOBLE LIES

Some of this mendacity emanates from ignorance. Pseudo-authorities often don’t know what a scientific truth is, what a political party stands for, or what a relatively accurate deconstruction of the social world would be like. As a consequence, they misinform us because they don’t know what they’re talking about. Moreover, the ignorant who teach us are often themselves taken in by and profess support for … demagogues and charlatans. Unable or unwilling to see the world through a critical lens, our teachers are purposely misled by a cadre of individuals who deceive them, and they in turn deceive us. A circle of ignorance is the result, which often takes centuries for truth to penetrate. However the ignorant are not completely blameworthy, inasmuch as they cannot decipher the propaganda and persuasion which peddle a constant stream of nonsense. Nonsense is all around, as are the credulous who are ready to believe it. This ignorance explains many of the untruths communicated to us throughout our lives, but we are especially susceptible when we are young.

But sometimes the deceit—regarding the difference between appearance and reality—takes the form of what Plato called a “noble lie.” The idea is to lie to someone for their own or society’s (supposed) good. Such lies are reminiscent of the saying, variously attributed to a number of people upon hearing the theory of evolution: “My dear, descended from the apes! Let us hope it is not true, but if it is, let us pray that it will not become generally known.” Surely there are lies told by those who believe their lies to be beneficial. These liars are not ignorant of the truth, but want to protect us from it. If belief in gods or country help us, then why undermine those beliefs? But while it may be beneficial for some to not know the truth, to deceive them for this reason is paternalistic. This may be appropriate for children–not to tell them about war, violence, hypocrisy and all the rest–but to lie to adults like this blatantly disregards their autonomy.

But worse than ignorance or noble lies are ignoble lies. Here the liars know the truth yet conceal it for self-interested reasons. These lies are perpetrated by churches, capitalists, and demagogues who lie about: a changing climate, the effects of tobacco, the benefits of universal health care, their own access to the gods, the truths of science, the injustice of the economy, and so much else. When we realize that individuals repress and distort truth for their own benefit, we have discovered something truly sinister. We have found perhaps the closest thing in the world to what the religious call sin. We have unearthed the truth-suppressors; the enemies of humanity who add layers of film to cover up their insidious ways. Tragically, because of such people, idealists often transform into cynics. After all, why love truth and pursue it, when others are so intent on distorting and covering it up?

THE POINT OF UNCOVERING UGLINESS

But now the situation seems even worse. With the deceptive layers of reality removed, we encounter a world of pain and suffering, of depravity and immorality, of lust and greed, of ignorance and purposeful lying. We have grown up, but in some ways wish we hadn’t. The world is not what our parents or our storybooks promised. And here surely is the origin of the cliche that ignorance is bliss. Who wants to see the bad side of life? Why become conscious if it reveals the abhorrent? Why not remain pollyannaish? Because ignorance is not bliss; ignorance is unconsciousness. And that’s no way to go through life for being conscious of the repulsive is the prerequisite for betterment. Honestly facing the worst, we have a chance of creating the best.

A similar realization must have come to Victor Frankl in the concentration camps. Without any illusions about life given his experiences there, he found a deeper meaning than most, a meaning that guided him for the rest of his life. In the concentration camps–places where indescribable grotesqueness replaced the beauty of life–he did not deny the reality of his situation, nor did he imagine it the precursor to a heavenly afterlife. Instead, he transformed himself, and a small part of the world too, by recognizing and confronting the evil that surrounded him. He surely knew the mismatch between the lies, hypocrisy, and horrors he encountered, and the world he had imagined as a child. But this recognition did not destroy him; instead, he was edified.

Thus removing the layers of hypocrisy, corruption, and lying gives us a chance to see things as they really are and improve them. And while this doesn’t tell us specifically what we should do; it does tell us what we shouldn’t do. We shouldn’t lie to ourselves and others about where we came from, what we are, and what the truth is as best we can determine it. Life is hard enough when we must act based on the truth; but if we must choose based on lies we are truly lost.

OUR MINDS AND HEARTS

Of course, none of this implies that we possess truth while others wallow in ignorance. All we profess, and all one can profess given our limitations, is that we should be honest truth-seekers, telling the truth as faithfully as we can. This implies never distorting the truth for personal gain and proclaiming the truth even when it is not in our best interest to do so.

Such reflection has brought us a long way from youthful innocence. We have discovered that truth is often buried, not because of defects in our truth-seeking methods, but from layers of lying. When we engage in purposeful lying, truth is a casualty and we are all worse off. In such a world, truth-lovers are left heart-broken.

But then, just as despair sets in, life goes on. New parents love their children … again; young thinkers seek truth honestly … again; idealistic youth work to relieve suffering … again; and new love transforms into older more mature love … again. The good is all around. Our hearts can be filled.

April 5, 2023

A Monopoly on Truth

Truth, holding a mirror and a serpent (1896). Olin Levi Warner, Library of Congress

Truth, holding a mirror and a serpent (1896). Olin Levi Warner, Library of Congress

As a follow-up to my recent post about truth, I would like to clarify what I see as the grave danger of being certain that one possesses the truth. As for truths in the natural sciences our concerns are irrelevant. Science by its nature is provisional; it is always open to contrary evidence and willing to adjust its views based on new evidence. Thus arrogant dogmatism is virtually impossible given the scientific method. The attitude of searching for truth and accepting provisionally what the evidence reveals prevents the kind of absolute certainty which is our main concern.

However, when humans believe strongly in areas where truth is difficult or perhaps impossible to attain, or where truth might not even exist, the situation is dire. Unlike in science, where the evidence constrains our thinking, in religion, for example, one can believe virtually anything. Moreover, these beliefs are often held with great fervency. It takes no willpower to believe in gravity or evolution—because the evidence overwhelms an impartial viewer—whereas in religion it often takes much faith. If we combine fervency of belief with strong faith we have a potent mix. If we feel strongly and we reject anything that will contradict our beliefs, naturally we may soon regard our beliefs as infallible. Crusades, inquisitions, persecution, and religious wars are the natural outgrowth of such attitudes. The great American philosopher John Dewey reflected on our concerns:

If I have said anything about religions and religion that seems harsh, I have said those things because of a firm belief that the claim on the part of religions to possess a monopoly of ideals and of the supernatural means by which alone, it is alleged, they can be furthered, stands in the way of the realization of distinctively religious values inherent in natural experience…. The opposition between religious values as I conceive them and religions is not to be abridged. Just because the release of these values is so important, their identification with the creeds and cults of religions must be dissolved.

The contemporary American philosopher Simon Critchley also captured our revulsion at arrogant dogmatism in a column in the New York Times entitled: “The Dangers of Certainty: A Lesson From Auschwitz.” Critchley advocates tolerance regarding our assessment of other persons; thereby rejecting the certainty that leads to arrogance, intolerance, and dogmatism.

The play of tolerance opposes the principle of monstrous certainty that is endemic to fascism and, sadly, not just fascism but all the various faces of fundamentalism. When we think we have certainty, when we aspire to the knowledge of the gods, then Auschwitz can happen and can repeat itself. Arguably, it has repeated itself in the genocidal certainties of past decades. … We always have to acknowledge that we might be mistaken. When we forget that, then we forget ourselves and the worst can happen.

Critchley also includes a moving video excerpt from Dr. Jacob Bronowski, a British mathematician, and polymath. In the old video, Bronowski visits Auschwitz, where he reflects on the horrors that follow when people believe themselves infallible. The video serves as a testimony to remind all of us of our fallibility.

March 30, 2023

You Can’t Go Home Again

My high school class will have a 50th reunion this year. I am not going. If I didn’t live 2000 miles away I might go, but I doubt it. For one thing, I went to a Catholic High School and anyone who has read my writings knows that I rejected Catholicism fifty years ago. So I would feel somewhat out of place around a lot of Catholics. For another, I don’t drink alcohol and I eat a whole food plant-based diet. So there is almost nothing I can order from a typical restaurant. Call me crazy but I want to reduce my chances of getting heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. And for another thing, Missouri is a Trump state, which could make conversation with about half the attendees problematic. Finally, I haven’t seen any of these people in many years so any connection I once had between them has been lost.

These sentiments also somewhat apply to family. For example, my siblings and their spouses and my nieces and nephews are, for the most part, Trump-supporting, Catholics. Fine people just not my preferred crowd. However, the connection with family runs deeper so more compromises must be made in order to accommodate these differences. Nonetheless, this is difficult as religious fanaticism and fascist politics repulse me.

But all this got me thinking about the idea of seeing old friends. While there is something bewitching about the idea of returning to the past, recapturing lost youth, and rekindling old friendships, there is also something futile about the attempt.

Yes, there are a few old friends that when I see or talk to them it’s as if not much has changed and we pick the conversation right up from when I last saw them even if it has been many years. There are others with whom it was pleasant to catch up but not much more comes of it. After all, I have lived all over the country and no longer live near my old friends. The fact is that I will almost certainly never see them again.

And then there are others that I realize that we have, to use a cliche, grown apart. This reminds me of a Leave It To Beaver episode I watched as a kid. Beaver can’t wait to have his old friend over but when his friend arrives he finds that both he and his old friend have changed. They no longer have much in common. This would be the case in which, for example, the religious or political views of old friends or family members are foreign to me and we can thus no longer recreate our past. Perhaps then we should focus on our current friends, the ones we are connected with now, rather than chasing chimeras.

Still, I realize these sentiments may have to do with the fact that I left my hometown over 30 years ago. If I had stayed there, perhaps I would have grown closer to those friends instead of making new ones along the way. But as I moved the old friends are slowly lost and replaced by new ones. With rare exceptions, my old friends from St. Louis, Las Vegas, Cleveland, Austin, and Ellensburg are no longer a part of my life primarily because I just don’t see them anymore.

Now don’t get me wrong. I can think of some old friends I would be delighted to see but my emphasis is now on my friends in Seattle. They are the ones I see and interact with; the ones I can help and who can help me. Moreover, there are lots of potential friends out there to meet in the future with whom I might find myself compatible.

To sum up these “off the top of my head” remarks I refer readers to a theme of Thomas Wolfe’s novel You Can’t Go Home Again. In it the novel’s protagonist states,

“You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood … back home to a young man’s dreams of glory and of fame … back home to places in the country, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting, but which are changing all the time – back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.”

And the reason is that things are radically impermanent. As Heraclitus‘ says “One cannot step in the same river twice”

Despite all this, I’m guessing that many of my old high school friends will find joy in seeing their old friends. I certainly understand that. And they won’t have my “can’t go home again” problems because they never left home—physically or psychologically. Perhaps they’ll even find something new in their old friends, or make new friends by meeting old acquaintances, or find new friends they didn’t know back then. Any of this would be great.

But I can’t go home again. Whatever I would return to wouldn’t be the same as what I left, and I am different too. For the Buddhists life’s transitory, impermanent, fleeting, ephemeral nature is one of the three marks of existence. Nothing—no idea, being, state of mind, or thing—endures. To reject this is to be blind to what life really is.

I’ll end with a quote first shared with me by a colleague when I was a young assistant professor over 30 years ago. It’s from Tennyson’s Ulysses,

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethrough

Gleams that untravelled world, whose margin fades

For ever and for ever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!

As though to breathe were life.

March 27, 2023

Does The Truth Matter?

Suppose you are literate in a precise subject like the mathematical or natural sciences. Suppose you know how the communicative property works, how to factor polynomials or the formulation of the quadratic equation. Suppose you know that atomic, relativity or evolutionary theory are true beyond any reasonable doubt, that plate tectonics occupies a fundamental place in modern geology, or that the most recent report of the IPCC (the definitive international body on climate science made of thousands of climate scientists) says that the probability that humans are the main cause of global warming since the mid 20th century is between 95% and 100%.

Now suppose you encounter skeptics who doubt these scientific ideas. You are clearly right and they are scientifically illiterate about the scientific theory in question. (With the caveat that no knowledge is absolutely certain.) But what difference does it make? In a sense, it doesn’t seem to matter. They may get along better with their false beliefs than you do with your true ones. Whether they are flat earthers or evolution deniers they may be happy in their beliefs, and changing their mind may cause them cognitive dissonance.

But in another sense, the truth does matter. If we want to build a bridge we will need mathematical principles; if we want to understand flu viruses we need evolutionary theory; if we want to find oil we need geology; if we want to make chemicals we’ll need to understand the periodic table; and if we want to understand climate change we need to know basic physics. It may not matter if people privately believe they can find oil by using tarot cards, build highway bridges out of duck tape, or cure disease with incantations; but if you really want to find oil, build secure bridges, or fight disease you’ll need geology and engineering and modern medicine.

Of course, this may all seem obvious because the mathematical and natural sciences are so precise. But what of less precise sciences? If we turn to social sciences like economics, psychology, history, or political science the situation is a bit different. In these fields, even the experts sometimes disagree. I will say with certainty that there was a Roman Empire or a Holocaust in 20th-century Europe if I’m a legitimate historian, but exactly what led to the former’s decline or the latter’s existence is open to debate. Still, much hinges on these disciplines—many lives are affected by them—so it is important to find out what’s really true regarding their subject matter, not just what we want to be true. We must proportion our assent to the evidence, view the matter impartially—very hard to do given human psychology—and then act the best we can.

If we get to subjects like the humanities and aesthetics we are in the realm of relative, or nearly relative, truth. The truths about philosophy and religion, even if they are objective, are so difficult to discern and one often must accept disagreement and uncertainty. And when we get to what is a good movie, book, poem, food, or piece of art, the truth does seem subjective and relative. There just isn’t much point in fighting about whether broccoli really tastes good—that seems to be individually relative.

Other than where it seems there is no objective truth—the broccoli case—the truth certainly matters. And not just for public policy. If individuals believe falsehoods it may cost them money. If they think they can beat the odds in Las Vegas or that clairvoyants or palm readers can predict the future, they will pay for these false beliefs. False beliefs might even cost you your life. You may die in unjust wars because you believe the lies of politicians, or you may fail to wear a seat belt because you would rather be “thrown clear in an accident.” (This was actually a widely held belief in the early days of seat belts. I am not kidding!)

Thus we must distinguish between knowing what’s true and convincing others that something is true. Both are difficult. The first results from using the scientific method, from a careful and conscientious examination of the world. Scientists toil for years in their laboratories teasing a bit of truth out of reality and adjusting their beliefs on the basis of the evidence. (For more see Charles Sanders Pierce’s classic: “The Fixation of Belief.”) Convincing others is much more difficult, especially since many people cling to comfortable beliefs and intuitions, avoid cognitive dissonance, or simply enjoy being contrary, argumentative, and disagreeable. Add selection bias and the various reasoning errors that humans are prone to, and it is easy to see why it is difficult to change a mind.

In the end, we should continually reexamine our own beliefs—to rid ourselves of false ones–and state the case for those things about which we have great certainty—well-tested scientific theories for example. After that, there isn’t much we can do except hope that truth will win out in the end. This doesn’t mean I’m optimistic about this happening. I just believe that if the truth doesn’t matter, then nothing much else does.

March 23, 2023

Are We Overworked?

[image error]

Recently a couple of persons close to me, a man and a woman, confided how overworked and stressed they are. Both are full-time employees with six-figure jobs, highly educated and intelligent, with excellent family support, and loving children and spouses. How lucky they are compared to most of us. If anyone should be able to cope, they should.

I have no doubt this reflects a society gone mad. It reflects the lack of a social safety net in modern America, the transfer of wealth from working people—even six figure income people—to corporations and shareholders, a materialistic society obsessed with GDP, the residue of the Protestant work ethic, the devaluing of time spent doing anything but producing, the greed of many of the super-rich, and who knows what else. But when the most talented persons in society are not flourishing, something is wrong with society. (And how to even imagine the stress of parents working at minimum wage jobs—essentially indentured servitude.)

The basic solution has to do with a new social and economic system. It is simply indecent that the 85 richest people control as much wealth as the poorest half of the world, more than 4,000,000,000 people! Imagine if aliens landed on the planet and observed this level of inequality. What would they conclude except that they have discovered one of the most unjust social and economic systems in the universe?

But how do we change the world? Unfortunately, I don’t know, and I fear we must wait for human consciousness to expand beyond the bounds of conventional thought for this to occur. This has happened to a certain degree in some parts of the world. Scandinavia and much of Western Europe have much stronger social safety nets and more laid-back lifestyles than say the USA. Nevertheless changing the economic system of the world in a single lifetime is a tall order.

The other thing we can do is try to change ourselves. Meditation, exercise, adequate sleep, and a good diet may provide some help. But in the end, these are just coping mechanisms designed to deal with an out-of-control society. I simply don’t know the answer except to say that one should try, if economically feasible, to change their environment either by moving to another society or changing their lifestyle within the country in which they live.

However, as I write this a feeling of impotence overwhelms me. With workers working longer hours for less pay and the wealth of society redistributed to the very wealthy, solutions are hard to find. Much suffering will continue—it is ubiquitous—and humanity hasn’t even begun to live until it creates a better world. (Remember though that the world is in most ways better than its ever been.)

The pain of all this is overwhelming. To cope we must remember there are mountains and oceans to look at, love to be given and received, and, hopefully, some inner peace to be found. Someday humans will grow up and realize that toys, trinkets, and big houses and cars pale in comparison to the wealth of health and inner peace. In the meantime, we should do all we can to find the real wealth of human life.

With my most sincere wishes for my reader’s future health and happiness, I remain, as ever, a devoted blogger.

March 19, 2023

Music and Time’s Passing

[image error]

SCIENCE, PHILOSOPHY, AND TIME

There’s hardly a more perplexing topic than time. I had a graduate seminar called “Concepts of Time” almost 30 years ago where I did learn, among other things, the difference between the A and B series and other technical issues in the philosophy of time. Yet I still have no idea what time is or whether time is even real. (A view shared by a few physicists.) St. Augustine famously said: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.” Later, in Chapter XII of his Confessions, he responded to the question “What was God doing before He made heaven and earth?” with the answer, “He was preparing hell … for those who pry into mysteries.” He apparently meant this facetiously. To make matters worse modern physics uses mathematical models to combine space and time into a single continuum called spacetime.

But I’m less concerned with these abstract questions, and lack the training necessary to say something intelligent about them anyway. Instead I’m struck by the phenomenology of the consciousness of time’s passing, a fancy philosophical way of talking about the conscious experience of the movement of time, and also the experience of aging in general. Consider how some popular music, for example, has captured the passage of time.

CONTEMPORARY MUSIC AND TIME

The American singer-songwriter Five for Fighting (Vladimir John Ondrasik III) captures this by focusing on different periods in our lives and our experiences of them in his song “100 years.” Here the focus is on the fleetingness of time:

The American singer-songwriter Anna Nalick wrote these lines about our inability to transcend, stop, or rewind the flow of time in her song “Breathe (2 AM).”

But you can’t jump the track, we’re like cars on a cable,

And life’s like an hourglass, glued to the table

No one can find the rewind button now …

And the song “Sunrise, Sunset,” from the classic play “Fiddler on the Roof, ” beautifully captures time’s passing. Here we have parents reflecting on how fast their children have grown and, at the same time, how fast they must have aged too. Here the attitude toward the passage of time is at once wistful and melancholy

No doubt there are countless other songs that explore similar themes, but this sampling suggests there is something universal about this experience of time’s passage that evokes strong emotions. It is no wonder that religions have tapped into this by marking life’s salient moments like birth, marriage, and death.

March 16, 2023

Kant On Developing Talents

[image error]

The philosopher Immanuel Kant famously argued that you ought to develop your talents. In fact, he argued that we have an absolute duty to do so. But is he correct? Should you develop your talents?

I don’t think there is a “categorical imperative,” (something that commands independently of one’s desires) to develop your talents. If you enjoy developing a talent, then, by all means, do so; skills and achievements are human goods. Moreover, you’ll probably be happy as a by-product of developing such talents. (I’m assuming the talent in question doesn’t include harming others.)

But if you don’t enjoy developing a talent, or if developing it would be stressful, or if one isn’t interested in developing it, or if it would harm others then there is no moral imperative to do so. Just because I could be a good soldier, doctor or gymnast doesn’t mean I’m obligated to be one. No matter what the pursuit, if I don’t find satisfaction in it, it’s probably best not to pursue it.

But if you develop the skill and talents that you want to develop and that make you happy; then you have a good chance to be successful, as Thoreau said long ago:

I learned this, at least, by my experiment;

that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams,

and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined,

he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.

But this is all too idealistic. In our society, we are often forced to do things we don’t want to. In fact, most people in modern capitalistic societies do work that they would prefer not to do. And even those with high-paying, prestigious positions usually prefer sailing, traveling, or golfing to their jobs. This is an indictment of our system. Modern society does not create the conditions under which most can flourish. So what do we do? If we have no choice but to engage in alienated labor, then we must choose between that labor or homelessness—again, an indictment of our capitalistic system.

But if we are lucky to have a choice, Thoreau’s words ring true. We should then pursue our dreams and hope the rest of the world benefits from our choices. Oh, that there could be such a world!

Some men see things as they are and ask why. Others dream things that never were and ask why not. ~ George Bernard Shaw

March 9, 2023

Compatibility In Marriage

“Compatibility is an achievement of love; it must not be its precondition.” ~ Alain de Botton

Many of us live in cultures that stress compatibility as the prerequisite for a lifelong romantic partnership; this contrasts sharply with the idea that compatibility is something achieved through time, compromise, and effort. The touching scene above from “Fiddler on the Roof” takes the latter view. The compatibility and eventual love of these partners whose marriage was arranged was an achievement. (Note. Topol who played Tevya in this scene died today.)

And the psychoanalysis Erich Fromm offered a similar idea when he wrote, contrary to much of contemporary culture, that love is an art that “requires knowledge and effort [not] … a pleasant sensation … something one “falls into” if one is lucky.”

But the philosopher Alain de Botton has articulated this idea most clearly. He writes,

We seem normal only to those who don’t know us very well. In a wiser, more self-aware society than our own, a standard question on an early dinner date would be; “And how are you crazy?”

The problem is that before marriage, we rarely delve into our complexities. Whenever casual relationships threaten to reveal our flaws, we blame our partners and call it a day. As for our friends, they don’t care enough to do the hard work of enlightening us. One of the privileges of being on our own is therefore the sincere impression that we are really quite easy to live with.

We make mistakes, too, because we are so lonely. No one can be in an optimal state of mind to choose a partner when remaining single feels unbearable. We have to be wholly at peace with the prospect of many years of solitude in order to be appropriately picky; otherwise, we risk loving no longer being single rather more than we love the partner who spared us that fate.

Choosing whom to commit ourselves to is merely a case of identifying which particular variety of suffering we would most like to sacrifice ourselves for.

The person who is best suited to us is not the person who shares our every taste (he or she doesn’t exist), but the person who can negotiate differences in taste intelligently—the person who is good at disagreement. Rather than some notional idea of perfect complementarity, it is the capacity to tolerate differences with generosity that is the true marker of the “not overly wrong” person. Compatibility is an achievement of love; it must not be its precondition.

Romanticism has been unhelpful to us; it is a harsh philosophy. It has made a lot of what we go through in marriage seem exceptional and appalling. We end up lonely and convinced that our union, with its imperfections, is not “normal.” We should learn to accommodate ourselves to “wrongness”, striving always to adopt a more forgiving, humorous and kindly perspective on its multiple examples in ourselves and our partners.

I think this is a mature thoughtful description of real compatibility.

Reflections On “Compatibility is an achievement of love; it must not be its precondition.”

While the short quote expresses a great and important truth it needs to be further analyzed. [We’ll assume a standard definition of compatible—(of two things) able to exist or occur together without conflict.]

Question 1 – Is compatibility completely irrelevant?

I suppose that some compatibility between two people contemplating marriage would be good. For example, it would be nice if they spoke the same language and wanted to live in the same country, and perhaps agreed about politics and religion and whether they wanted children or not. This isn’t to say that such potential areas of disagreement couldn’t be resolved just that it would be easier to achieve success in a relationship if some basic ideas about how to live well were shared. So some compatibility may indeed be a prerequisite for a good marriage.

However many so-called differences between partners could be resolved and resolving them over time is a large part of what it is to have a successful relationship. Moreover, some conflict between people is inevitable no matter how hard they try to live harmoniously. We are never going to find someone with whom we are completely compatible; we are never going to find a clone of ourselves. In fact, we may even find living with our clone unbearable. So, contrary to Western cultural norms, I argue that the idea of compatibility as a precondition of a successful marriage is way overvalued in our culture.

Question 2 – How hard should we try to be compatible with our partners?

While the quote suggests that compatibility is an achievement there are limits to how hard one should try to be compatible. This is obvious in a case where, for example, a partner wants you to compromise on his plan to be a serial killer, physical abuser, child molester, or alcoholic. I’m sure there are other less obvious examples in which you are asked to compromise your core values. At some point though, compromise would entail losing personal autonomy. So there are limits to the extent to which you try to avoid conflict. But in other trivial examples, what color you prefer on your walls or car, compromise is easy. Obviously, there would be a lot of cases in between about managing money or raising children.

Question 3 – Is compatibility an achievement then?

For the most part, with the caveats listed above, yes it is. To live many long years with minimal conflict is the very definition of a successful marriage (and probably of a successful friendship, organization, etc.) This will be very difficult, and if we are self-aware the process will reveal to us our many flaws. But if successful this will provide us with one of the true enduring comforts of our lives. The comfort that we are not totally alone in this lonely universe, that someone else thinks about us, cares for us, waits for us, loves us, and overlooks our many shortcomings.

Question 4 – How do you know if a person is compatible enough?

On this I agree with de Botton, “the person who can negotiate differences in taste intelligently—the person who is good at disagreement.” This “capacity to tolerate differences with generosity” is the key. I’m not sure how you can determine this beforehand, but perhaps careful observation about another’s ability to tolerate differences rather than impose their will upon you is a good guide.

Nonetheless, there are no guarantees as people often deceive one another; it is simply risky to commit ourselves to someone who may not reciprocate. This suggests that longer courtships are generally better than shorter ones as there is more time for a person’s character to reveal itself thereby minimizing the risk of being hurt and betrayed. (This is from someone who got married a few months after meeting their wife. But I was just lucky that Jane is a remarkable woman who has tolerated me for so long.)

Question 5 – Are romantic relationships necessary?

Still, lives lived without romantic partnerships can be satisfying too. In the end, we are all ultimately alone in this vast spacetime and there are many ways to ameliorate our existential angst. We can create art, music, or literature; we can help other people; we can improve the world. A fulfilling life is one in which we become self-aware and use that knowledge to better the human condition, but none of this demands that we mate for life. Remember too that a bad relationship is far worse than none at all.

Question 6 – What’s the real problem?

Finally, let me say that most people think that the problem of finding compatible partners is one of being loved. Hence we try to make ourselves more marketable in the quest for partners. And I admit to having done this when I was young. But the real problem, it now seems to me as I approach 70, is one of learning to love. I don’t for a moment think I know how to do this, but this is the problem of love.

So it seems to me that loving others, whether they be lifelong partners, children, friends, or even strangers is the difficult part. But if we can learn to love … that will be its own reward.