John G. Messerly's Blog, page 18

March 5, 2023

Philosophy, Science, and Religion

[image error]

In order to more clearly conceptualize Western philosophy’s territory, let’s consider it in relation to two other powerful cultural forces with which it’s intertwined: religion and science. We may (roughly) characterize the contrast between philosophy and religion as follows: philosophy relies on reason, evidence, and experience for its truths; religion depends on faith, authority, grace and revelation for truth. Of course, any philosophical position probably contains some element of faith, inasmuch as reasoning rarely gives conclusive proof; and religious beliefs often contain some rational support, since few religious persons rely completely on faith.

The problem of the demarcation between the two is made more difficult by the fact that different philosophies and religions—and philosophers and religious persons within similar traditions—place dissimilar emphasis on the role of rational argument. For example, Eastern religions traditionally place less emphasis on the role of rational arguments than do Western religions, and in the east philosophy and religion are virtually indistinguishable. In addition, individuals in a given tradition differ in the emphasis they place on the relative importance of reason and faith. So the difference between philosophy and religion is one of emphasis and degree.

Still, we reiterate what we said above: religion is that part of the human experience whose beliefs and practices rely significantly on faith, grace, authority, or revelation. Philosophy gives little if any, place to these parts of human experience. While religion generally stresses faith and trust, philosophy honors reason and doubt.

Distinguishing philosophy from science is equally difficult because many of the questions vital to philosophers—like the cause and origin of the universe or a conception of human nature—increasingly have been taken over by cosmologists, astrophysicists, and biologists. Perhaps methodology best distinguishes the two, since philosophy relies on argument and analysis rather than empirical observation and experiment. In this way, philosophy resembles theoretical mathematics more than the natural sciences. Still, philosophers utilize evidence derived from the sciences to reformulate their theories.

Remember also that, until the nineteenth century, virtually every prominent philosopher in the history of western civilization was either a scientist or mathematician. In general, we contend that science explores areas where a generally accepted body of information and methodology directs research involved with unanswered scientific questions. Philosophers explore philosophical questions without a generally accepted body of information

Philosophical analysis also ponders the future relationship between these domains. Since the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, science has increasingly expropriated territory once the exclusive province of both philosophy and religion. Will the relentless march of science continue to fill the gaps in human knowledge, leaving less room for the poetic, the mystical, the religious, and the philosophical? Will religion and philosophy be archaic, antiquated, obsolete, and outdated? Or will there always be questions of meaning and purposes that can never be grasped by science?

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), one of the twentieth century’s greatest philosophers, elucidated the relationship between these three domains like this: “All definite knowledge … belongs to science; all dogma as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to theology. But between theology and science there is a no man’s land, exposed to attack from both sides; this no man’s land is philosophy.”

March 1, 2023

Philosophical Thoughts

[image error]

I have many ideas for blog posts but there are only so many I can do and research. Here are just a few that I’ve wanted to do but haven’t found the time. Posts about

The polymath Isaac AsimovThe physician and philosopher Albert SchweitzerRousseau on self-loveWhether it was worth it to become educatedHow enclosed we are in our thoughts, seeing the world mostly from our perspective.A theory of timeI’ll stop as the list could continue for a long time. I literally have almost 100 drafts of posts in my drafts folder. But there could be a million or a billion or a trillion. The sliver of things I can contemplate and experience is so limited. (I’m always struck by how much there is to learn and so little time to do it in.)

But even were I to be able to instantly download all human knowledge there is still so much I wouldn’t know. Suppose I could download all the knowledge of all other intelligent beings in the universe (assuming they exist) my knowledge would still be limited.

But even were I omniscient wouldn’t there still be things I wouldn’t know? After all, Godel showed that some mathematical propositions are true but can’t be known to be true. And if I know the velocity of a sub-atomic particle I can’t know its position and vice versa. So it seems that omniscience probably isn’t a coherent notion. I don’t know what it would mean to know everything. And even if I did, maybe the answer is just 42.

Contemplations like these make me feel lost in a vast universe. But then after a while, the contemplation subsides and life goes on. Here I’m reminded of David Hume,

“Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? … I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, environed with the deepest darkness, and utterly deprived of the use of every member and faculty.

Most fortunately it happens, that since Reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, Nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends. And when, after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.”

[image error]

February 26, 2023

Coping With Life

My recent post, “A Skeptic’s View of the Meaning of Life” elicited the following response from a regular reader.

[Your post] really gets at the heart of both a description of and the optimum response to the meaning-of-life dilemma, doesn’t it? … How in the world do we deal with the recognition of pointlessness while feeling a natural inclination to engage with life? … your reaction turns out to be exactly the same as mine that I characterized as “pure experience” in my “What’s It All About” essay: there is no solution, only a way to cope.

Reading your post gives me the same sort of comfort that Magee’s Ultimate Questions did in terms of confidence that my thoughts about MOL weren’t weird or a sign of weakness—his about a visceral reaction to the horror of it and yours, a reasoned reaction to living with it. Actually, the way you put it is probably more accurate than mine … It’s not limited to reflecting just the ethereal high of transcendent experience but is actually inclusive of a broad range of down-to-earth satisfaction to be found in much of everyday experience that makes us feel as if life is worth living even though we realize that nothing cosmically purposeful will come of it (so far as we can presently anticipate, a la Magee, anyway).

My response:

Sylvia, there is a lot to say here but I’ll comment briefly. I agree there is no ultimate intellectual solution to the meaning of life problem, only various ways to cope, as my grad school mentor wrote to me many decades ago.

As to your “what does it all mean” questions, you do not really think that I have strong clear replies when no one else since Plato has had much success! It may be more fruitful to ask about what degree of confidence one can expect from attempted answers, since too high expectations are bound to be dashed. It’s a case of Aristotle’s advice not to look for more confidence than the subject matter permits. At any rate, if I am right about there being a strong volitional factor here, why not favor an optimistic over a pessimistic attitude, which is something one can control to some degree? This is not an answer, but a way to live.

I also agree with you that meaning must be found in the small things as Simon Critchley has argued,

Critchley finds a similar insight in what the poet Wallace Stevens called “the plain sense of things.” In Stevens’ poem, “The Emperor of Ice Cream,” the setting is a funeral service. In one room we find merriment and ice cream, in another a corpse. The ice cream represents the appetites, the powerful desire for physical things; the corpse represents death. The former is better than the latter, and that this is all we can say about life and death. The animal life is the best there is and better than death—the ordinary is the most extraordinary.

Critchley considers Thornton Wilder’s famous play “Our Town,” which exalts the living and dying of ordinary people, as well as the wonder of ordinary things. In the play, young Emily Gibbs has died in childbirth and awakens in an afterlife, where she is granted her wish to go back to the world for a day. But when she goes back she cannot stand it; people on earth ignore the beauty which surrounds them. As she leaves she says goodbye to all the ordinary things of the world: “to clocks ticking, to food and coffee, new ironed dresses and hot baths, and to sleeping and waking up.” It is tragic that while living we miss the beauty of ordinary things. Emily is dismayed but we are enlightened—we ought to appreciate and affirm the extraordinary ordinary. Perhaps that is the best response to nihilism—to be edified by it, to find meaning in meaninglessness, to realize we can find happiness in spite of nihilism.

Putting it differently, as I have written previously,

Nothing then completely silences all our doubts and soothes all our worries—not the limited meaning life offers us, not the knowledge of a purpose, not the promise of hope, not the engagement in activity. How then do we proceed? We must accept something of our present life lest resentment causes us to curse it. Yet, at the same time, we must reject the present or nothing will improve. This creative tension acknowledges the limitations of reality as a starting point while rebelling against its shortcomings. It involves working to mold, create, and increase meaning. We don’t know that reality will progress, but if we partially accept our present reality, and if we dream of a future without limits and struggle to bring it about, then we may increase the meaning in our lives and in the world.

Yet for now, we are forced to live with uncertainty and angst—that is a testimony to our intellectual honesty and emotional integrity. Unlike those who adopt blind faith, we scorn the facile resolutions of the fearful. And if we must die, we will die as free people who did not yield to the forces that sought to destroy them from the moment of their birth. Those are the forces we seek to defeat, but which have not yet been defeated. In the meantime, we should relish the limited joy and meaning life offers, work to eliminate human limitations, and suppress negative thoughts as best we can.

This is no solution, only a way to live.

February 19, 2023

Different Kinds of Love

[image error]

I have discussed love in a number of previous posts: “On Love and Pain,” “Human Relationships on a Sliding Scale,” “Romantic Love and the Idea of Settling,” “We Must Love One Another or Die,” “Is Love Stronger Than Death?” and “The Art of Loving.” But it occurs to me that we need to carefully define love.

The Different Kinds of Love

The Greeks distinguished at least 6 different kinds of love:

1) Eros was the notion of sexual passion and desire but, unlike today, it was considered irrational and dangerous. It could drive you mad, cause you to lose control, and make you a slave to your desires. The Greeks advised caution before one gives in to these desires.

2) Philia denoted friendship which was thought more virtuous than sexual or erotic love. It refers to the affection between family members, colleagues, and other comrades. However, these people are much closer to you than Facebook friends or Twitter followers.

3) Ludus defines a more playful love. This ranges from the playful affection of children all the way to the flirtation or the affection between casual lovers. Playing games, engaging in casual conversation, or flirting with friends are all forms of this playful love.

4) Pragma refers to the mature love of lifelong partners. After a lifetime of compromise, tolerance, and shared experiences calm stability and security ensue. Commitment between partners is the key; they mutually support and respect each other.

5) Agape is a radical, selfless, non-exclusive love; it is altruism directed toward everyone (and perhaps to the environment too.) It is love extended without concern for reciprocity. Today we would call this charity; or what the Buddhists call loving-kindness.

6) Philautia is self-love. The Greeks recognized two forms. In its negative form philautia is the selfishness that wants pleasure, fame, and wealth beyond what one needs. Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection, exemplifies this kind of self-love. In its positive form, philautia refers to proper pride or self-love. We can only love others if we love ourselves, and the warm feelings we extend to others emanate from good feelings we have for ourselves. If you are self-loathing, you will have little love to give.1

These distinctions undermine the myth of romantic love so predominant in modern culture. People obsess about finding soul mates, that one special person who will fulfill all their needs—a perpetually erotic, friendly, playful, selfless, stable partner. In reality, no person fulfills all these needs. And the twentieth-century commodification of love renders the situation even worse. We buy love with engagement rings; market ourselves with clothes, body modifications, Facebook profiles, and on internet dating sites; and we look for the best object we can find in the market given an assessment of our trade value.

This is not to suggest that everything is wrong with the modern world or that the internet isn’t a good place to find a mate—it may be the best place. (Although I’m much too old to worry about it!) Rather I suggest that to be satisfied in love, as in life, one must cultivate multiple interests, strategies, and relationships. We may get the most stability from our spouse, but find playful times with our grandchildren or our golfing partners; we may discover friendship with our philosophical comrades; and we might find an outlet for altruism in our charitable contributions or in productive work.

As for our most intimate relationships, we should lower our expectations—again no one satisfies all our needs. As I said in my previous post, this is not the idealized love of Hollywood movies, but it is real love. No, you won’t have heart palpitations every time you see your beloved after 35 years, but you will feel the presence that accompanies a lifetime of shared love, a lifetime of struggling and fighting and working together. You will feel the continuity of knowing someone who knew you when you were young, middle age, and old, and they will feel the same. The accompanying serenity is peaceful and priceless. I hope everyone can experience this.

1. Rousseau made a similar distinction between amour-propre and amour de soi. Amour de soi is a natural form of self-love; we naturally look after our own preservation and interests and there is nothing wrong with this. By contrast, amour-propre is a kind of self-love that may arise when we compare ourselves to others. In its corrupted form, it is a source of vice and misery, resulting in human beings basing their own self-worth on their feeling of superiority over others.

February 12, 2023

The Serenity Prayer and Hope

[image error]Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971)

The Serenity Prayer is the common name for a prayer written by the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. The best-known form is:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

I’ve never thought deeply about the prayer—although it certainly came up in the classes I taught. However, the video below by the philosopher Luc Bovens titled “Want a Meaningful Life? Learn to Control Your Mind,” got me thinking more about it. Bovens believes that the prayer presents a false dichotomy. He argues that there is a space between serenely accepting and courageously changing—and that space is best filled by hope. Hope lies between active change and passive acceptance.

Now consider how this applies to Bovens’ topic in the video below—living a meaningful life. We cannot act so as to guarantee that life is meaningful, but we shouldn’t just accept that it is meaningful either. What we can do is act in the hope that life is meaningful while accepting that we can’t be assured that it is. So hoping involves both active and passive components. And this is an alternative to the choices offered by the prayer’s false dichotomy.

Here is Bovens explaining this.

February 8, 2023

Time, Death, and the Meaning of Life

[image error]

In my last post, I reviewed Sabine Hossenfelder’s Existential Physics: A Scientists Guide To Life’s Biggest Questions. However, I failed to comment on one of its essential passages concerning time, death, and meaning. It involves the block universe or eternalism, the Einsteinian idea that “there is no basis for singling out a present time that separates the past from the future because all times coexist with equal status.”1 Hossenfelder explains what this means with this simple image,

… once your grandmother dies, information about her—her unique way of navigating life, her wisdom, her kindness, her sense of humor—becomes, in practice, irretrievable. It quickly disperses into forms we can no longer communicate with and that may no longer allow an experience of self-awareness. Nevertheless, if you trust our mathematics, the information is still there, somewhere, somehow, spread out over the universe but preserved forever. It might sound crazy, but it’s compatible with all we currently know.

In other words, as Hossenfelder writes later,

According to the current laws of nature, the future, the present, and the past all exist in the same way. That’s because, regardless of what you mean by exist, there is nothing in these laws that distinguishes one moment of time from any other. The past, therefore, exists in just the same way as the present. While the situation is not entirely settled, it seems that the laws of nature preserve information entirely, so that all the details that make up you and the story of your grandmother’s life are immortal.

Now I have been aware of the idea of the block universe since I was a graduate student in Richard Blackwell‘s seminar “Concepts of Time.” I also mentioned how eternalism was significant in my latest book, Short Essays on Life, Death, Meaning, and the Far Future,

Some might still find it distressing to think that their individual consciousness, despite its role in creating cosmic meaning, will have faded into oblivion long before new heights of meaning are reached. But maybe this view of time is mistaken and future meaning is already a part of us, and we are a part of it… now. After all, Einstein’s theory of special relativity implies that objects and events from the past, present, and future all exist eternally and are all equally real.

I didn’t explore the idea further but Hossenfelder has reminded me how such a pursuit might be fruitful. I have hesitated to explore this idea further because 1)I don’t have the mathematical background to really understand physics at more than a basic layperson level and 2) I have always found it hard to reconcile the strong intuition of time’s passing (presentism) with Einstein’s block universe. Let me explain.

Much of modern science is counterintuitive. Who really can conceptualize atoms much less subatomic particles? Other than experts, who really understands quantum mechanics or relativity theory? I can say that the electrons in my hand are repulsed by the electrons in the wall thus preventing them from passing through, and I’ve said this in class. But as a non-expert, I have only a vague understanding of such ideas.

Now I accept all this because I understand the power and truth of modern science but eternalism has always been hard to grasp. My parents and grandparents just seem as dead to me as I will seemingly be to my children and grandchildren. It is just a hard intuition to avoid. Now again I know that intuition is a poor guide to truth. If it were I’d think that the planet was flat and not moving beneath my feet—both ideas obviously false but quite intuitive. But the past and future being as real as the present—that’s a hard idea to feel in your bones.

Of course, Hossenfelder and others continue to remind me of this and I’ll hopefully have time to think more about this in the next few years. I’d better do so soon because it feels as if I’m running out of time!

___________________________________________________________________

1.”The quantum theory of time, the block universe, and human experience,” in The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, Joan A. Vaccaro, 28 May 2018.

February 5, 2023

Review of Sabine Hossenfelder’s, “Existential Physics”

[image error]

Sabine Hossenfelder is a German theoretical physicist, science communicator, author, musician and YouTuber. She is currently employed as a research fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. Her new book, Existential Physics: A Scientists Guide To Life’s Biggest Questions is outstanding. Her simple and clear explanations make even the most complicated issues in physics accessible even to the uninitiated. Most importantly she shows how issues in modern physics and cosmology relate to deep existential questions about life’s meaning. In the process, she guides us through questions about how the universe began, and how it will end, whether the past is still real, whether copies of us exist somewhere, whether physics has ruled out free will, whether consciousness is computable, and whether humans are predictable. She also investigates whether the universe thinks, whether it was made for us, whether it is all mathematics, and whether we can create a universe.

In the Epilogue “What’s The Purpose of Anything Anyway?” she addresses questions of meaning with both insight and humility. She begins by admitting that science doesn’t have, and almost certainly never will have, all the answers to life’s biggest questions. But, in addition to its practical implications, Hossenfelder practices science in order to make sense of her life. And this leads to the book’s final question “What’s the meaning of life in the universe revealed by modern science?” She believes that each person must answer this question for themselves but she tells a simple story to explain how she thinks about the issue.

When she was young she asked her mother “what’s the meaning of life?” Her mother was a teacher and she replied that for her “the meaning of life is to pass along knowledge to the next generation.” At the time Hossenfelder thought her mother’s answer was “rather lame. [But] Thirty years later I have come to pretty much the same conclusion.” For most of her life, she has studied the laws of nature and still takes great joy in sharing that knowledge with others. She has found that many people want to know how the universe works because we want to make sense of ourselves and our place in the universe.

Ultimately, Hossenfelder writes that she is trying to do her part “to aid the universe’s understanding of itself.” As she concludes, “So, yes, we are bags of atoms crawling around on a pale blue dot in the outer spiral arm of a remarkably unremarkable galaxy. And yet we are so much more than this.”

February 2, 2023

It’s Groundhog Day

[image error]

[image error] [image error]

Groundhog Day has long been one of my very favorite movies. On one level it is a very funny movie; on another, it is a particular take on Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence. It is definitely a film that rewards rewatching. In fact, the legendary film critic Roger Ebert reviewed it twice and included it in his list of great movies. In his 2005 review he says:

“Groundhog Day” is a film that finds its note and purpose so precisely that its genius may not be immediately noticeable. It unfolds so inevitably, is so entertaining, so apparently effortless, that you have to stand back and slap yourself before you see how good it really is.

The film is about a jerk who slowly becomes a good man. Listen to Ebert again:

His journey has become a parable for our materialistic age; it embodies a view of human growth that, at its heart, reflects the same spiritual view of existence Murray explored in his very personal project “The Razor’s Edge[image error].” [Another of my favorite movies.] He is bound to the wheel of time, and destined to revolve until he earns his promotion to the next level. A long article in the British newspaper the Independent says “Groundhog Day” is “hailed by religious leaders as the most spiritual film of all time.”

The movie is about a guy named Phil, played by Bill Murray, who is living the same day over and over again. He is essentially immortal. In the scene below, Phil’s co-worker Rita, played by Andie McDowell, recites a few lines of poetry. Here are the lines that precede the ones she recites:

High though his titles, proud his name,

Boundless his wealth as wish can claim

Despite those titles, power, and pelf,

And here is the scene in which she recites the poem’s next lines:

The wretch, concentred all in self,

Living, shall forfeit fair renown,

And, doubly dying, shall go down

To the vile dust from whence he sprung,

Unwept, unhonored , and unsung.

(from “Breathes There The Man,” an excerpt from “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,”

~ Sir Walter Scott.)

No matter how famous or wealthy, narcissists are among the worst of humankind.

January 31, 2023

Thoughts At The End Of January, 2023

[image error]

I have previously written about the difference between how the world is and how we imagine it could be. Today I was thinking about the problem from the microcosmic point of view—the difference between what I am and what I wish I could be. Why is so much of our potential never actualized?

In response, I immediately think of Aristotle’s distinction between act and potency. Roughly speaking Aristotle thought that everything is a composite of form and matter. The form is the pattern or structure of a thing and the matter is what makes something an individual thing. Everything you see around you is a formed matter. Then he associated matter with potency and actuality with form. The idea is that matter has the potential to be actualized in different forms. For our purposes, the important point is that just as acorns have the potential to become oak trees, humans have potentials that they may or may not actualize.

My first thought is that all of us have the potential to be many things but human finitude demands that only some of our potential is actualized. This seems endemic to the human condition. Perhaps you and I could have been physicians or violinists or accountants. Or better golfers of tennis or soccer players. No worries, we can’t have been and done everything we wanted to.

But my shortcomings go beyond having or not having a particular career or being better at a sport. Why I am not more generous, patient, kind, gentle, profound, or loving? This isn’t to say that I don’t possess some of these qualities, but if I’d like to be a better person, to possess one or more of these qualities in greater abundance, why is this so hard?

The first answer that comes to mind is that my long evolutionary history, encoded deep within my genes, presents a barrier to much of what I’d like to be. For example, I’m wired to be somewhat selfish, territorial, and aggressive. Still, it seems that I should be able to overcome many of these less noble parts of my nature. Indeed Aristotle thought that potential can be actualized by taking the right action. But it is both hard to know which is the right action and commit to that course of action even if you know it’s the right one.

In the end, I don’t know exactly why we, like the world we live in, find this gap between what we imagine and what is. The gap between the potential for good and the actuality of so much evil. As Russell so eloquently put it “… the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be.” I suppose all we can do is try to make our little part of the world a little better. That’s not much of an answer after 60 years of education but it’s about the best I can come up with today. Perhaps our descendants will arrive at a greater understanding of reality.

In the meantime, looking at all the shortcomings both in the world and in myself, maybe the sentiments expressed by the serenity prayer are about the best we can do.

January 26, 2023

Why Do People Believe Crazy Things?

[image error][image error]

(Akim Reinhardt’s superb essay about the proliferation of online conspiracy theories was published at 3 Quarks Daily on MONDAY, AUG 16, 2021. Reprinted with permission.)

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

[image error]

Rokeach hypothesized that since Jesus exists by the same code that the Immortals in Highlander later stated as “There can only be one,” these three men might be cured of their delusions when confronted with others who insisted likewise. Of course, he was very wrong. Much like Highlander’s Immortals, they simply fell into conflict. When faced with the others’ unrelenting presence, each dug their heels in and doubled down on their delusions. Even Rokeach’s jaw-dropping manipulations, which included a string of outrageous lies and elaborate fabrications, could not dissuade them.

I’ve recently been pondering this infamous tale of poorly conceived psychological experimentation because in it I see reflections of problems currently plaguing America. Except instead of being thrown together in confinement, people with similar mental disorders are now finding each other on their own. And instead of a psychological professional at least trying (albeit in a highly flawed manner) to cure them, the medium of connection is the largely unregulated and even more manipulative internet. And, finally, instead of insisting there can only be one, mentally ill people are now reinforcing and reduplicating each other’s delusions.

Of course you don’t have to be mentally ill to believe most of the world wide web’s whack-a-doo conspiracy theories. One need merely be stupid or gullible, or in most cases perhaps, just a bit desperate. Take for example the entirely discredited “theory” that childhood vaccines cause autism. It is very understandable that the trauma of conceiving and parenting a severely autistic child would break someone just a little bit, to the point that they demand an explanation that satisfies them more than what we currently know about autism’s causes, which is very little. For some, “very little” just won’t do. Furthermore, the little we do know, including that genetics might be a factor, may contribute to a sense of misplaced guilt that some simply cannot shoulder, leading them to grasp at whatever else is out there. And what’s out there is an internet-fueled story about vaccines.

Funnel it through the internet, and suddenly it’s the conspiracy theory that’s infectious, spreading from the desperate to the naive. By 2011, 18% of Americans believed this incredibly dangerous hooey. That’s roughly 50 million people.

Likewise, you don’t have to be mentally ill to sincerely believe that the Earth is flat, that the Holocaust is a hoax, that the moon landing was faked, that Princess Diana was murdered, that 9-11 was an inside job, or that JFK was killed by the CIA or the Mafia or the Cubans. You might very well be mentally ill. But you don’t have to be.

However, as we move up the ladder to more and more ludicrous internet conspiracy theories, it begins to seem as if some sort of mental illness is a prerequisite for full faith. That is not a professional assertion. Psychology as a Natural Science was a fun course, but not life changing. I stuck with my major and became a Historian, not a mental health professional, and I respect professional boundaries. But just as any reasonable person can make lay interpretations about the past, any reasonable person can conclude that your brain must not be working properly if you sincerely believe that the world’s leading politicians, business leaders, and artists are actually blood-sucking Lizard People from outer space responsible for the Holocaust and 9-11, and hell bent on ruling the world and enslaving humanity.

The appropriate lay word here would be “crazy.” That’s what I said to my partner about a new friend who began sending her Lizard People conspiracy theory emails. Not as a joke, which is what my partner first assumed. But as educational material. As in, this is real. “Your new friend is crazy,” I told her. “Stop hanging out with her.” She did. Yet the emails about Lizard People and other lunacy continued. So she blocked her.

But of course it’s not so simple. At least not for us as a society. This isn’t about just three avatars of Christ locked up in an Ypsilanti hospital, with any other people clinging to the same delusion scattered and isolated across the country. There are hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions who believe either in Lizard People or other outrageous conspiracies. And they are not scattered. They are not isolated. They are finding each through the internet, where they reinforce and expand their delusions and recruit new believers, just as this woman attempted to recruit my partner. They are voting. They are running for office. They are serving in Congress. They were among those who stormed the Capitol at the president’s urging, and attempted to violently overturn a national election.

It wasn’t always this way, even when it was.

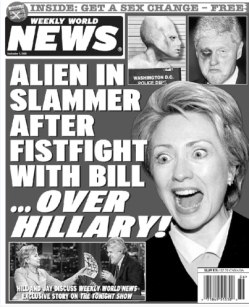

Here in the United States, Boomers and Gen Xers remember the “newspapers” one used to find for sale at the supermarket checkout aisle. Classic impulse buys, they were pure frivolity that no right-thinking person would put into their basket while hunting for food to sustain yourself and your family. Rather, you might buy it on a lark now that the brunt of the chore is done, as you unload your items onto the conveyor belt and begin to realize you’re actually under your budget. Why not buy something silly like watermelon flavored diet breath mints? Or a cheap, little toy your kid is wound up about? Or a some celebrity gossip rag? Or better yet, some absolutely ridiculous piece of trash like the Sun or Weekly World News, with their mix of weird-but-true stories, and completely fabricated yarns.

Inside their pages you would find the reliable, stock folk tales, such as Big Foot and the Loch Ness Monster. Then there was the in-house taradiddle, such as explorers finding The Garden of Eden; or Bat Boy, the half-bat, half-human child living in a West Virginia Cave; or various space aliens, including one named P’lod who was having an affair with Hilary Clinton. Who would actually believe such fatuousness?

Just about everyone knew these were jokes, and those who were gullible enough to believe them generally kept quiet about it. After all, when everyone around you says this is a joke, you might just give up on it. Or at least keep it to yourself rather than face the inevitable mockery.

However, one of these tongue-in-cheek absurdities struck a chord. When the WWN ran a story claiming that the dearly departed, gone-far-too-young Elvis Presley was still alive, it resonated with readers. It must have been something about Elvis; similar stories about JFK, Marilyn Monroe, Hank Williams Sr., and Adolph Hitler still being alive didn’t generate anywhere near the same buzz. But the Elvis story took off. People laughed. Soon it was a running joke for Johnny Carson, David Letterman, and other comedians. A pre-web meme had been born.

However, one of these tongue-in-cheek absurdities struck a chord. When the WWN ran a story claiming that the dearly departed, gone-far-too-young Elvis Presley was still alive, it resonated with readers. It must have been something about Elvis; similar stories about JFK, Marilyn Monroe, Hank Williams Sr., and Adolph Hitler still being alive didn’t generate anywhere near the same buzz. But the Elvis story took off. People laughed. Soon it was a running joke for Johnny Carson, David Letterman, and other comedians. A pre-web meme had been born.

For most people, the notion of a gray-haired Elvis sneaking in and out of movie theaters was so preposterous that it became something funny to spoof. Yet some people insisted it was true. When the story first came out, WWN offices, much to their surprise and delight, fielded dozens of phone calls from people wanting to know more. Some were willing to believe that Elvis wasn’t really dead after all.

Given that the entire Christian religion, with its two and a half billion believers, is predicated on more or less the same thing, I guess it’s understandable.

No, I did not just say that every theistic religious adherent is mentally ill. The actual nature of “mental illness” as a socially constructed category is for another time. Rather, the point is that back in the late 20th century, while some people could still fall for a brand new shenanigan such as Elvis is alive!, the popular purveyors of poppycock were not powerful enough to spread genuine conspiratorialism very far. Yes, there were some who believed Elvis was still alive, but their numbers were contained. Straight faced rags like the Weekly World News and the Sun could turnout only so many true believers because anyone seriously subscribing to their silliness still lived in a society that indulged these tales only to lampoon them. Either you were mocking or being mocked; and having nearly everyone mock you is a serious inhibitor.

But the internet is not just a few small publications available only at grocery checkout aisles. It is, for practical purposes, infinite, and nearly as omnipresent as one wants it to be. Worse yet perhaps, it is algorithmic. More and more of it is intentionally designed to find you, grip you, and draw you together with both, like minded people and manipulative bots coded to feed your frenzy. There are now fellow Christs from Ypsilanti everywhere, and countless Dr. Rokeaches, none of them manipulating you in pursuit of a cure but only to reinforce your misbeliefs so as to profit from them politically and/or economically.

The tide has turned. Instead of 99% of America mocking your outlandish beliefs, and perhaps no one you personally know agreeing with them, the internet connects believers and reinforces and spreads beliefs. Many people you know online, and even in person, now agree with you completely. Under these circumstances, the conspiracies become infectious, spreading from those who are susceptible because of mental illness to those who get caught up in the craze, much like the roughly 50 million Americans who eventually believed, casually or deeply, in the autism vaccine conspiracy. At least that one had an air of faux science about it. Now we’re nearly overrun by far fetched lunacy.

The exact numbers are impossible to discern, but whatever the tally, it is far too high. People joining together around their belief in Lizard People from space enslaving us. Or that Hilary Clinton (she does seem a popular target for this claptrap) and other top Democrats ran a child sex trafficking ring from the basement of a Washington D.C. pizzeria located in a building that literally has no basement. Or that the mass shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High were faked, and that student survivors and parents of murdered grade schoolers are actually paid “crisis actors.”

No matter how crazy they are, there’s a special place in Hell for people who harass the parents of murdered seven year olds.

But it’s probably somewhere between Lizard People and the faux science of vaccine autism where the real danger lies. Despite mountains of evidence against the conspiracy and none for it, 32% of Americans, including 53% of Republicans believe Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election only because of massive voter fraud. Say otherwise and face their wrath. It doesn’t matter who you are. Even a Trump-loving, war veteran, sitting Republican Congressman who denies the conspiracy becomes a target of public scorn.

Now you’re the one being mocked.

Akim Reinhardt’s website, which collects no data, does not track you, makes no effort to join you with the likeminded, and pedals only the bestest conspiracies, is ThePublicProfessor.com