John G. Messerly's Blog, page 19

January 23, 2023

Dinner For Nietzsche: Rhythms, Rituals, And Eternal Return

Stone where Nietzsche reports having had the inspiration for his ‘eternal return’, with commemorative plaque.1

( This essay was originally posted on 3 Quarks Daily, JAN 9, 2023, by JOCHEN SZANGOLIES. Reprinted with permission.)

Time presents itself, depending on the context, under two different modalities: cyclical and linear. Linear time moves always forward, carrying us from past to present, ever towards an uncertain future; while circular time, the time of clock hands, sunrise and sunset, and recurring seasons, sees us back again at our origin.

These would seem to be somewhat in tension. But I find that time, perhaps like all the great mysteries, is only enriched by its seeming contradictions. Take ‘stopping time’, as it is sometimes portrayed in movies—that is, holding everything frozen. How long does such a state last? What is the difference between it lasting an hour, a day, or an eternity? In the absence of change, time is robbed of duration. But in an instant of time, there can be no change. Hence, any instant, it seems, might as well be an infinity, held in the palm of your hand.

We have just come out the tail end of one of the cycles of time punctuating our lives, and emerged into a new one—at least according to the Gregorian calendar. Perhaps it is natural, then, to muse about the way time seems to both sweep us away while, on the arc traced by the Earth around the Sun, always returning us to the same places again—changed, but the same.

Nietzsche was the great augur of time’s cyclical nature. Perhaps the following quotation has shown up on your social media feed in recent weeks:

For the New Year. — I still live, I still think: I still have to live, for I still have to think. Sum, ergo cogito: cogito, ergo sum. Today everybody permits himself the expression of his wish and his dearest thought: hence I, too, shall say what it is that I wish from myself today, and what was the first thought to run across my heart this year—what thought shall be for me the reason, warranty, and sweetness of my life henceforth. I want to learn to see more and more as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all and all and on the whole: someday I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.

For Nietzsche, the concept of amor fati—the love of one’s fate—was tied deeply to the idea that all that is, was, and will be, will be again: the notion of the eternal return of all things. In a time-honored philosophical tradition, Nietzsche, in The Gay Science, lets a demon introduce the concept, having him proclaim:

This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence.

The question, then, is: would you, confronted with this revelation, ‘throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse’ the demon—or have you ever experienced a moment where you would instead proclaim him a god and call it the most divine thing you ever heard?

Or, as Nietzsche lets the prophet put it towards the end of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “if you ever said, ‘You please me, happiness! Abide, moment!’ then you wanted all back. All anew, all eternally, all entangled, ensnared, enamored…” In each moment, recall, there hides an eternity, so to want it once is to want it forever, and to want it with all the rest.

There is, I think, a concept unfamiliar to the present Zeitgeist in these lines: the celebration of what is, the embrace of the wish to have what one has, and nothing more, in perpetuity. Today, we would think of this as stasis, lack of progress, a failure to get out of one’s comfort zone—we are always entreated to want more, to not be satisfied, to seek improvement and perfection. Have a ‘growth mindset’. While there is nothing wrong with trying to better yourself, we are forever locked in unrest and dissatisfaction, driven towards a ‘more’ that is always lessened upon being attained.

In this sense, our society has become Faustian, rebuking Nietzsche’s demon with what Faust proposed to Mephistopheles:

When I say to the Moment flying;

Linger a while—thou art so fair!

Then bind me in thy bonds undying,

And my final ruin I will bear!

(Werd ich zum Augenblicke sagen:

Verweile doch! du bist so schön!

Dann magst du mich in Fesseln schlagen,

Dann will ich gern zugrunde gehn!)

Thus, Faust is so certain that he will never be satisfied, never find a moment he considers fit to remain in, to return to, that he stakes his very soul on it. Of course, Faust ends up having a devil of a time with his bargain; so maybe, there is grounds for a critical look at our rejection of the same-old, same-old (but ever re-affirming) in favor of the always-new (but ultimately self-denying).

The Same Procedure As Every YearTime’s cycles are often marked by ritual, and none more so than the turning of the great celestial clock. One of the most cherished rituals in Germany is to usher in the new year by watching the 1963 comedy sketch Dinner for One, recorded in black and white by the NDR (you can watch it here, if you’re not familiar).

The plot is simple enough: Miss Sophie intends to celebrate her 90th birthday, and has invited her four closest friends. Unfortunately, they have all since passed; nevertheless, she is unwilling to forgo the ritual, and thus, her butler James stands in for each. As this includes a toast with an alcoholic beverage at each course of the evening’s meal, contributing to a progressive inebriation, hijinks, as they are wont to, ensue.

Commemorative ‘Dinner for One’-stamp.I can’t quite say how the tradition came about, but it’s taken seriously—up to half of all households catch at least one of the various showings on New Year’s Eve, and it is the most often repeated programme on German television. In 2018, Deutsche Post even issued a commemorative stamp. My father’s laughter, always renewed at the always same cues, is a fond childhood memory.

The sketch is, in my unqualified opinion at least, a hilarious masterclass in comedic timing, but I doubt that alone is reason for its popularity. And it must strike one as quite strange: comedy, resting to some degree on surprise, seems to be the genre least well-suited to repeated viewing. But I think there is a lesson here, about what one might call the willing suspension of inurement: to let the new return, as new, again and again. To suspend the modern, cynical seen-it-all attitude in favor of a renewed, wilfull naiveté that renounces all pretense of aloof sophistication in favor of laughing, again, again, and then again at James’ struggle with the tiger’s head.

To see this, we must unpack another of time’s paradoxes: how both its linear and its cyclical modality dwell each within the other. Consider what it might mean to live one’s life again: that one has lived once, followed by another iteration. But what is there to distinguish one from the other? Faced with some number of such cycles, how could we tell which one might have been the first, the second, the thousandth? Which one is lived, and then, which is the one to be lived again? To do so, these cycles must themselves, like beads on a string, be arrayed in linear form: first one, then the other, then the next. Time’s circularity presupposes time’s linearity.

Prague’s astrological clock: measuring linear time by the periodic orbits of the planets.2

But then, how do we know time’s linear aspect? We saw that without change, there is no duration; hence, change is necessary to mark time. But not any change will do: rather, to mark time, we depend on sequences, revolutions (of clock hands or planets, or indeed societies)—in short, it is periodic, cyclic systems that allow us to delineate what is meant by a second, a minute, a day. To give linear time a measure, we need to find its rhythm. In that sense, time’s linearity presupposes time’s circularity.

Dinner for One reflects this at several levels. James, the butler, walks the same circle around the table again and again; Miss Sophie toasts her (impersonated) friends in always the same sequence; but most obviously, the same exchange repeats between the protagonists: in preparing to serve each course, James asks, “the same procedure as last year?”, which is met with a stern, “the same procedure as every year, James,” with a poignant stress on ‘every’. Clearly, we are to understand that things will be as they were, ever to return to their point of origin.

But we are also shown that circular time is always less than exact, leaving us at a point that is almost, but not quite exactly the same. The sun rises every day, but every day at a slightly different time; wintertime these days is warmer than it used to be. At some point, James manages to avoid the treacherous tiger’s head; coming ever more under the influence, each repeat performance of the toasting ritual is a less than faithful recreation of its predecessor. But most obviously, where once sat Miss Sophie’s friends, there are now only empty chairs: time marches on, even as it ever returns.

New Year, Old Me AnewThe passage of time is always accompanied by loss: or, as the physicist in me would put it, entropy always increases. Time’s teeth eventually gnaw down all we build—“for all that comes to be, deserves to perish wretchedly”, as Mephistopheles puts it. In the face of this, we might well appeal to time’s cyclical nature as salvation—or try to take matters into our own hands, as in Martin Suter’s novel Die Zeit, Die Zeit (‘the time, the time’), where a man tries to bring back his dead wife by rearranging his house and the surroundings so as to perfectly recreate a time when she was still alive—reasoning that time doesn’t exist, only change does.

Temporal ordering: each instant, each snapshot contains a memory of a previous one. Thus, we could arrange them according to what came earlier.3

Strangely enough, there is some support for such a notion in physics: the phenomenon of Poincaré recurrence means that a dynamical system, typically after a very long time, will return to a state arbitrarily close to its initial state (provided the system is bounded in a certain sense, and nothing ‘flies off to infinity’). Taking things a step further, physicist Julian Barbour has indeed argued that there is no such thing as time, there are only moments—little slivers of eternity—which differ from each other in small details, and are ordered only in retrospect, by ‘later’ ones carrying traces—memories or records—of their predecessors, like a picture of a picture.

But this misses something about the ethical dimension of time, which expresses itself differently in both the linear and circular modes. In linear time, our actions echo forth, never to be recalled, no matter the depth of our regret; in circular time, to live a good life, with Nietzsche, is to live a life you could face up to living again (and again). Each demands a care for the future that is absent from the burn-your-bridges rat-race to the top that demands constant self-reinvention and Faustian dissatisfaction, and that is equally negated by the attempt to undo time’s progression.

This care for the future is really the future’s care for us, as Rilke realized: “The future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens.” We are the future, manifested in the present, in order to bring itself about. Care for the future is care for ourselves, and we must account for it in terms of the paradox of both its eternal return and eventual loss.

Thus, on the cusp of this new year, perhaps we should not put so much emphasis on the overcoming of the past, but instead, on becoming the future, and then becoming it again and again: while this year will, undoubtedly, bring new trials, opportunities, happiness and grief in its own mix, try to live it with amor fati in the small. Even though this year, like every year, is unique and irretrievable, we should wish for it to be such that that, at its end, if we are asked, “the same procedure as last year?”—we can answer: “the same procedure as every year.”

_______________________________________________________________________

1.Image credit: Kuebi = Armin Kübelbeck, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

2. Image credit: By Andrew Shiva / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

3. Image credit: picture by Rachael Crowe on Unsplash

January 16, 2023

Sean Carroll: The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe

[image error] [image error]

I have just finished Sean Carroll’s The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. One of the most enjoyable books I’ve read in a long time—so carefully and conscientiously crafted. Carroll brings his considerable erudition, unusual even for a scholar, to bear on a number of salient philosophical topics including:the essence of his poetic naturalism; the non-existence of gods; why the universe exists; the mind-body problem; the extraordinary philosophical implications of quantum field theory; why death is the end; the evolution of consciousness; why we aren’t the point of the universe; neuroscience and freedom; the is-ought problem, and many more.

But I will focus on the last part of the book, which covers meaning, morality, and purpose. Carroll argues that while such concepts aren’t a part of the Core Theory of quantum fields they are real nonetheless. In other words, they aren’t built into the structure of the world but “they emerge as ways of talking about our human-scale environment.” But this doesn’t mean that the search for meaning is another kind of science. Instead, searching for a good and meaningful life is about evaluating and judging how we ought to live.

Most importantly, meaning is not derived from Gods, built into the universe itself, nor is it some transcendent aspect of reality. Rather, it is found inside the world. Meaning is a concept that humans invent to talk about the world—real but invented by us—just like the rules of basketball or bathtubs, or novels. As Carroll writes, “it’s up to you, me, and every other person to create meaning for ourselves.”

Now some people worry that if values and purpose and meaning aren’t objective then they aren’t real or don’t matter. But whether you are moved by the belief that such things are objective or not, you can still value and care and love. You can want to help the less fortunate because you think that’s what God wants you to do or because you just think it’s the right thing to do.

A second worry is how to start creating meaning in a universe that doesn’t tell us how to do it. Carroll addresses such worries by appealing to our basic biology, with our desire to “move, process information, and interact with our environment.” We have desires, we care “about ourselves, about other people, about what happens in the world.” We can reflect on our desires and change them; our desires “make us who we are.” And from our desires, we construct the meaning and purpose of our lives. “The world, and what happens in the world, matters. Why? Because it matters to me. And to you.” Starting with our personal desires we may even find meaning in something larger than ourselves.

Carroll’s thought is especially characterized by wonder; he is passionately curious about how the universe works. What is important according to Carroll is to make an effort to try to understand reality. In order to do so we might tell the story of a God who created both the universe and us and with whom we will (hopefully) be reunited after death. He understands the appeal of the story and why some try to reconcile it with modern science.

But Carroll thinks a different story is much more likely to be true. The universe is no miracle, it simply is. It has evolved “from a state of low entropy toward increasing complexity, and it will eventually wind down to a fearless equilibrium.” This unguided process brought creatures such as ourselves into being, and with us “meaning and mattering into the world.” This may not totally satisfy us, “but it fits comfortably with what science has taught us about nature.” Given this realistic view of reality, he claims that it is up to us to make life what we want it to be.

Carroll grants that such a view of reality “calls for a bit of fortitude” and may bring about “the need for some existential therapy.” Floating in a purposeless universe we wonder what it’s all about. But that same universe is knowable and trying to understand it can be extraordinarily rewarding.

In the end “we all share the same universe, the same laws of nature, and the same fundamental task of creating meaning and mattering for ourselves and those around us in the brief moment of time we have in the world.”

January 11, 2023

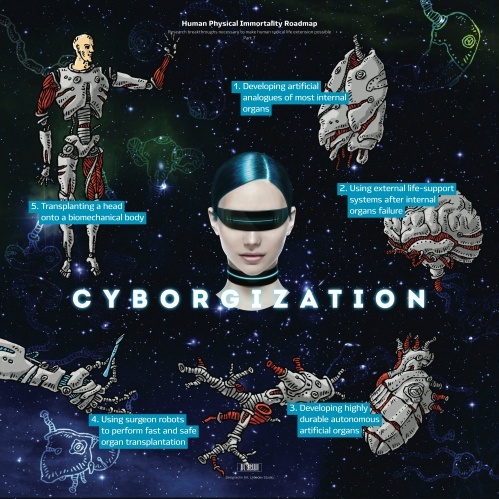

Can Science Make Us Immortal?

[image error]Human chromosomes (grey) capped by telomeres (white)

If death is inevitable, then all we can do is die and hope for the best. But perhaps we don’t have to die. Many respectable scientists now believe that humans can overcome death and achieve immortality through the use of future technologies. But how will we do this?

The first way we might achieve physical immortality is by conquering our biological limitations—we age, become diseased, and suffer trauma. Aging research, while woefully underfunded, has yielded positive results. Average life expectancies have tripled since ancient times, increased by more than fifty percent in the industrial world in the last hundred years, and most scientists think we will continue to extend our life-spans. We know that we can further increase our lifespan by restricting calories, and we increasingly understand the role that telomeres play in the aging process. We also know that certain jellyfish and bacteria are essentially immortal, and the bristlecone pine may be as well. There is no thermodynamic necessity for senescence—aging is presumed to be a byproduct of evolution —although why mortality should be selected remains a mystery. There are reputable scientists who believe we can conquer aging altogether—in the next few decades with sufficient investment—most notably the Cambridge researcher Aubrey de Grey.

If we do unlock the secrets of aging, we will simultaneously defeat many other diseases as well, since so many of them are symptoms of aging. Many researchers now consider aging itself to be a disease that progresses as you age. There are a number of strategies that could render disease mostly inconsequential. Nanotechnology may give us nanobot cell-repair machines and robotic blood cells; biotechnology may supply replacement tissues and organs; genetics may offer genetic medicine and engineering; and full-fledged genetic engineering could make us impervious to disease.

Trauma is a more intransigent problem from the biological perspective, although it too could be defeated through some combination of cloning, regenerative medicine, and genetic engineering. We can even imagine that your physicality could be recreated from a bit of your DNA, and other technologies could then fast forward your regenerated body to the age of your traumatic death, where a backup file with all your experiences and memories would be implanted in your brain. Even the dead may be resuscitated if they have undergone the process of cryonics—preserving organisms at very low temperatures in glass-like states. Ideally these clinically dead would be brought back to life when future technology was sufficiently advanced. This may now be science fiction, but if nanotechnology fulfills its promise there is a reasonably good chance that cryonics will be successful.

In addition to biological strategies for eliminating death, there are a number of technological scenarios for immortality that utilize advanced brain scanning techniques, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The most prominent scenarios have been advanced by the renowned futurist Ray Kurzweil and the roboticist Hans Moravec. Both have argued that the exponential growth of computing power in combination with advances in other technologies will make it possible to upload the contents of one’s consciousness into a virtual reality. This could be accomplished by cybernetics, whereby hardware would be gradually installed in the brain until the entire brain was running on that hardware, or via scanning the brain and simulating or transferring its contents to a computer with sufficient artificial intelligence. Either way, we would no longer be living in a physical world.

In fact, we may already be living in a computer simulation. The Oxford philosopher and futurist Nick Bostrom has argued that advanced civilizations may have created computer simulations containing individuals with artificial intelligence and, if they have, we might unknowingly be in such a simulation. Bostrom concludes that one of the following must be the case: civilizations never have the technology to run simulations; they have the technology but decided not to use it, or we almost certainly live in a simulation.

If one doesn’t like the idea of being immortal in a virtual reality—or one doesn’t like the idea that they may already be in one now—one could upload one’s brain to a genetically engineered body if they liked the feel of flesh, or to a robotic body if they liked the feel of silicon or whatever materials comprised the robotic body. MIT’s Rodney Brooks envisions the merger of human flesh and machines, whereby humans slowly incorporate technology into their bodies, thus becoming more machine-like and indestructible. So a cyborg future may await us.

The rationale underlying most of these speculative scenarios has to do with adopting an evolutionary perspective. Once one embraces that perspective, it is not difficult to imagine that our descendants will resemble us about as much as we do the amino acids from which we sprang. Our knowledge is growing exponentially and, given eons of time for future innovation, it easy to envisage that humans will defeat death and evolve in unimaginable ways. For the skeptics, remember that our evolution is no longer moved by the painstakingly slow process of Darwinian evolution—where bodies exchange information through genes—but by cultural evolution—where brains exchange information through memes. The most prominent feature of cultural evolution is the exponentially increasing pace of technological evolution—an evolution that may soon culminate in a technological singularity.

The technological singularity, an idea first proposed by the mathematician Vernor Vinge, refers to the hypothetical future emergence of greater than human intelligence. Since the capabilities of such intelligences are difficult for our minds to comprehend, the singularity is seen as an event horizon beyond which the future becomes nearly impossible to understand or predict. Nevertheless, we may surmise that this intelligence explosion will lead to increasingly powerful minds for which the problem of death will be solvable. Science may well vanquish death—quite possibly in the lifetime of some of my readers.

But why conquer death? Why is death bad? It is bad because it ends something which at its best is beautiful; bad because it puts an end to all our projects; bad because all the knowledge and wisdom of a person is lost at death; bad because of the harm it does to the living; bad because it causes people to be unconcerned about the future beyond their short lifespan; bad because it renders fully meaningful lives impossible; and bad because we know that if we had the choice, and if our lives were going well, we would choose to live on. That death is generally bad—especially for the physically, morally, and intellectually vigorous—is nearly self-evident.

Yes, there are indeed fates worse than death and in some circumstances, death may be welcomed. Nevertheless for most of us most of the time, death is one of the worst fates that can befall us. That is why we think that suicide and murder and starvation are tragic. That is why we cry at the funerals of those we love.

Our lives are not our own if they can be taken from us without our consent. We are not truly free unless death is optional.

January 8, 2023

Grant Wahl’s Death: Why Lying Is So Harmful

[image error]Grant Wall (1973-2022)

This morning I was moved by reading Dr. Celine Grounder’s brief New York Times opinion piece about the death of her young husband and all the cruelty it has elicited and the ignorance it has revealed. I highly recommend reading the tribute to her deceased husband.

While Dr. Grounder rightfully focuses on the extraordinary ignorance that connects covid vaccination to every death—there is no connection between the two whatsoever—I would also like to consider those who are NOT ignorant of the truth about the extraordinary efficacy of covid vaccines, but who nonetheless LIE about the issue for personal gain. (Yes, Fox News has a very strict covid vaccination and testing policy. Lying for profit is ubiquitous.)

In my long teaching career, I told students many times that lying—despite being common and seemingly innocuous—was a serious moral failing and the cause of incalculable suffering. It often has, as Dr. Grounder writes, terrible and cruel consequences.

The issue came up in ethics classes when students would ask about the existence of universal moral principles. The point was that if none existed then morality must be (personally or culturally) relative. In search of such universal principles, students would often quickly suggest something like killing infants, even though infanticide is found in many cultures, or to other forms of murder even though capital punishment, human sacrifice, and war, have been justified by many cultures.

While the exact number of universal imperatives is disputed—a typical claim is that there are at least 7 universal moral imperatives—truth-telling is generally recommended by cultures. In other words, as far as I know, most cultures have a prescription against lying.

And the reason is straightforward. Without the assumption of truth-telling, communication is pointless. If I ask you what time it is and you say 5 pm even though it’s noon, there was no point in asking the question. If I ask you how to get to Los Angeles and you tell me to fly to Boston and then head north for 100 miles, there wasn’t much point in asking the question.

Now, these lies are small potatoes compared to the Big Lie about the stolen 2020 election or to the lies of Alex Jones about the children murdered in Newtown CN. or the over 30,000 lies Trump told in just a few years, or the thousands of lies told by Limbaugh, Hannity, Carlson, Bannon, Stone, Conway, Huckabee Sanders, Santos, and all the rest, but it does reveal how central truth-telling is to a functioning society.

There is such a temptation to lie because it’s often in one’s self-interest but it is also so collectively damaging. (One of the basic issues of ethics–self-interest vs morality.) Truth-telling is often hard but society can’t fully flourish without it; the damage it causes is incalculable.

FInally, I’m so sorry for Dr. Grounder’s loss and the cruelty and ignorance she has had to endure but I thank her for her courageous and thoughtful essay.

January 4, 2023

Dan Fogelberg – River of Souls

Peoria Riverfront Park Dan Fogelberg Memorial Site

Peoria Riverfront Park Dan Fogelberg Memorial Site

“To every man the mystery

Sings a different song

He fills his page of history

Dreams his dreams and is gone.”

Below is a music video of the most thoughtful song I’ve ever heard about death, one that appeals to me in my occasional mystical moments. The words, music, and vocals are by the American musician Dan Fogelberg (1951 – 2007), who is best known for his hit songs

such as: “Longer,” “The Leader of the Band,” and “Same Old Lang Syne.” (The story of each of these songs is itself fascinating, just follow the links.)

The song about death is titled “River of Souls” and is from an album of the same name. Below you’ll find its sublime lyrics.

[image error] River of Souls (Original Recording Remastered)[image error]

[image error] River of Souls (Original Recording Remastered)[image error]

I take my place along the shore

And I wait for the tide

It seems I’ve passed this way before

In an earlier time

I hear a voice like mystery

Blowing warm through the night

The silent moon embraces me

And I’m drawn to her light

I follow footprints in the sand

To a circle of stone

Find a fire burning bright

Though I came here alone

And in the play of shadows cast

I can dimly discern

The shapes of all who’ve gone before

Calling me to return

There are no names

That fit these faces

There are no lines that can define

These ancient spaces

The spirits dance across the ages

And melt into a river of souls

Lo que es de mio ~~ what is mine ~~

Lo que es de dios ~~ what is god’s ~~

Lo que es del rio ~~ what is the river’s ~~

Melt into a river of souls

I take my place along the shore

And I wait for the tide

It seems I’ve passed this way before

In an earlier time

To every man the mystery

Sings a different song

He fills his page of history

Dreams his dreams and is gone

There are no names

That fit these faces

There are no lines that can define

These ancient spaces

The spirits dance across the ages

And melt into a river of souls

Lo que es de mio ~~ what is mine ~~

Lo que es de dios ~~ what is god’s ~~

Lo que es del rio ~~ what is the river’s ~~

Melt into a river of souls

(There are links to his other music below.)

I highly recommend the music  of this talented singer-songwriter.

of this talented singer-songwriter.

Thank you Dan for your artistic contributions. I hope you have melted into a river of souls.

December 28, 2022

A Skeptic’s View of the Meaning of Life

I received a correspondence from a reader who wonders about “the triumph of judgment over spontaneity as we emerge from childhood into adulthood and the consequent obstacle it poses for living in psychic comfort.” In other words, she worries about how to reconcile “a naturally felt purposefulness and zest for life against an intellectual sense of life’s essential pointlessness and its indifference to human concerns that give rise to the recognition of absurdity.” The only consolation she experiences is with her grandchildren “as they go about engaging the world with perfect unmediated wonder, boundless energy, and demands for attention.”

I too have felt this tension. When I watch the delight my young granddaughter takes in looking at every flower and insect, when I sense the innocent eyes through which she sees the world, I am saddened beyond words. Like any adult, I know the ugliness of the world that waits to trample on that innocence. I clearly see the contrast between childlike wonder and optimism and the pessimistic conclusions about reality that mature reasoners often draw. Given this tension, how do we carry on without accepting some silly supernaturalism?

There are a number of strategies we might adopt here. We might follow Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning) and conclude that the problem of life is not learning to live with its absurdity—since we can’t know for sure that it is absurd—but to learn to live not being sure if life is meaningful or not. Or we might follow a philosopher like E. D. Klemke (Summary of E.D. Klemke’s “Living Without Appeal“) who held that we can find subjective meaning in an objectively meaningless world by responding positively to its beauty. As Klemke put it: “if I can so respond and can thereby transform an external and fatal event into a moment of conscious insight and significance, then I shall go down without hope or appeal yet passionately triumphant and with joy.”

Still, I agree with my reader that no amount of intellectual reflection ever fully dispels our deepest existential concerns. For the movement of time spoils even those things that make us happy and which, for the moment, give our lives purpose. This passage of time haunts us; that perpetual perishing which diminishes our joy by its intrusion into the present. This radical impermanence and our consciousness of it reminds us that our own demise rushes toward us as the present recedes away. The awareness of our impending doom is a constant companion capable of poisoning our momentary happiness, leading in turn to the inevitable realization that it is not just we who may die, but our children, and their children, and all children, and, in the end, all of reality as well.

Reaching the limits of the intellect’s power to dissuade our existential fears, perhaps we can be comforted by an exuberant affirmation of the meaning found in life’s activities. Any serious student of philosophy is struck by the stark contrast between the somber tone of our philosophical musings, and the joy we feel through our immersion in the world of the senses. In the mountains and oceans we see, in the walks we take and the meals we eat, in the joy we find in physical play and philosophical talk, and in the warmth we feel when surrounded by those that love us and whom we love, there we don’t so much find meaning as transcend the need for it. At those times life is sufficient unto itself. When we laugh and play and love, all the misery of the world momentarily vanishes. We hardly give meaning a thought. And if thought brings existential anguish back again—perhaps we can and should think less. In short, we live deeper than we can think.

But is living with less thinking a realistic antidote? Can we live this way after reflectivity has become interwoven into our natures? Can we live constantly in motion, so that troubling thoughts do not disturb? No, we cannot suppress our most important questions indefinitely. For after laughing and playing and loving, thought returns. Why is happiness so fleeting? Why must we suffer and die? Why do we all meet tragic ends? What if all is for naught? We cannot avoid our questions for long; eventually, we drop our guard and they return.

But even if we could avoid our deepest questions, should we? I don’t think so. Our questions bring forth the deep reservoir of our inner life that is often hidden from normal viewing, and our curiosity and inquisitiveness ennoble us, differentiating us from less conscious beings. Our thinking may not make us happy, but it nourishes a deep interior life. However much we love the world of body and sense, thought is our salient feature. We should not repress it. And, since we cannot and should not evade our questions, the prescription to find meaning in activity only partially satisfies. No matter what we think or do, our questions remain.

Nothing then completely silences all our doubts and soothes all our worries—not the limited meaning life offers us, not the knowledge of a purpose, not the promise of hope, not the engagement in activity. How then do we proceed? We must accept something of our present life lest resentment cause us to curse it. Yet, at the same time, we must reject the present or nothing will improve. This creative tension acknowledges the limitations of reality as a starting point while rebelling against its shortcomings. It involves working to mold, create, and increase meaning. We don’t know that reality will progress, but if we partially accept our present reality, if we dream of a future without limits and struggle to bring it about, we may increase the meaning in our lives and in the world.

Yet for now, we are forced to live with uncertainty and angst, as a testimony to our intellectual honesty and emotional integrity. Unlike those who adopt blind faith, we scorn the facile resolutions of the cowardly. And if we must die, we will die as free people who did not yield to the forces that seek to destroy them from the moment of their birth. Those are the forces we seek to defeat, but which have not yet been defeated. In the meantime, we should relish the limited joy and meaning life offers, work to eliminate human limitations, and suppress negative thoughts as best we can. This is no solution, only a way to live.

__________________________________________________________________________

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 194

December 20, 2022

Betrand Russell’s Message to Future Generations

Above is Bertrand Russell, one of my intellectual heroes, around age ninety, talking about the most important lessons he would leave to future generations. And below is an excerpt from Russell’s essay “How To Grow Old.” It is one of the most beautiful reflections on death in all of world literature.

The best way to overcome it [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.

No other philosopher in my more than 50 years of studying philosophy has provided me with as much insight, clarity, and comfort as Russell.

December 2022, Seattle, Washington, USA

December 16, 2022

Economists – The USA Desperately Needs More Immigrants

My previous speculations that the USA desperately needs to increase immigration have been confirmed by major economists as reported in “Trump’s Immigrant Crackdown Left A Critical Shortage Of Workers In U.S. Economy.”

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has estimated that the economy is short an astonishing 3.5 million workers, and economists estimate half of those workers would typically be migrants allowed into the country, The Washington Post reported Thursday.

“There is no question: We need more immigration,” Adam Ozimek, chief economist at the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan public policy organization, told the Post.

“Immigrants aren’t just workers, they are particularly flexible, mobile workers who help address acute labor shortages wherever they emerge,” he added. “And that’s particularly important in this constrained economy we’re facing right now.”

The key is to understand the valuable role immigrants play in national economies. “They … do jobs Americans turn down, such as low-paying, physically demanding work in the hospitality, agriculture, construction and health care industries.” And a shortage of workers leads “to higher prices as employers raise wages to lure workers to jobs.”

Moreover, as Giovanni Peri, director of the Global Migration Center at the University of California, Davis, says, “it could be another four years before the country makes up for current shortfalls through more legal immigration. Even then, he told the Post, it won’t be enough to catch up to the aging American workforce, which will leave millions of more positions unfilled.”

To highlight a few other concerns about immigration people may have I’d refer them to the short essay “The Great American Bigot.” It states that

A paper published in 2020 by the Cato Foundation (co-founded by Charles Koch and not exactly a liberal organization) found that crime rates among illegal immigrants were 782 per 100,000, among legal immigrants 535 per 100,000, and—wait for it—1,422 per 100,000 among native born Americans.

Moreover, it is well-documented that immigrants are 80% more likely to start a business than those born in the U.S., and that the number of jobs created by these immigrant-founded firms is 42% higher than native-born founded firms, relative to each population.

Furthermore, “As We Live Longer, How Should Life Change? There Is a Blueprint” investigates, among other things, the fact that the population in the USA is aging and its birthrate continues to decline. One result of these demographic trends is that social security is now expected to be unable to pay full benefits by 2033, as there are fewer young working people paying the tax and contributing to the system.

In conclusion, the economic self-interest of Americans to increase immigration is overwhelming, and the bigotry that often underlies opposition to immigration is self-defeating.

___________________________________________________________

For some anecdotal evidence, I’ve recently seen help wanted/now hiring signs on UPS and USPS trucks—very desirable jobs—at multiple grocery and other retail stores, at restaurants and bars, etc. A grocery store near me offered a starting salary of $21 an hour.

December 14, 2022

Susan Wolf on Happiness and Meaning

Susan R. Wolf (1952 – ) is a moral philosopher who has written extensively on meaning in human life. She is currently the Edna J. Koury Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She addressed the topic of the meaning of life, among other places, in her essay: “Happiness and Meaning: Two Aspects of the Good Life.”

Wolf begins by asking: “In what does self-interest consist?” Now the concept of self-interest is straightforward: “Self interest is interest in one’s own good. To act self-interestedly is to act on the motive of advancing one’s own good.” But the content of self-interest—what really is in our self-interest—is problematic.

To better understand the content of self-interest (SI) she follows Derek Parfit’s distinction between three types of SI: 1) hedonistic theories which connect SI with happiness construed as pleasure and lack of pain; 2) preference theories which hold that SI is whatever you want even those things don’t make you happy or give pleasure; and 3) objective-list theories in which SI is independent or prior to one’s preferences. Wolf argues that meaningfulness is an element or ingredient of a good or happy life, and she is thus committed to meaning being in one’s SI in the objective-list sense for the goodness of a meaningful life “does not result from making us happy or its satisfying the preferences of the person whose life it is.” Still. meaningful lives will generally be fulfilling and thereby make us happy.

Next Wolf claims that our need for meaningful lives center on questions of whether life is worth living has any point, or provides sufficient reason to go on. Paradigms of meaningful lives include lives of moral or intellectual accomplishment, whereas meaningless lives include those lived in quiet desperation or in futile labor. In short, Wolf claims that: “… meaningful lives are lives of active engagement in projects of worth.”

Active engagement refers to being griped or excited by something. Active engagement relates to being passionate rather than alienated about something, whereas being engaged is not always pleasant since it may involve hard work. Projects of worth suggest that some objective value exists, and Wolf argues that meaning and objective value are linked. While Wolf offers a philosophical defense of objective value she claims that “there can be no sense to the idea of meaningfulness without a distinction between more and less worthwhile ways to spend one’s time, where the test of worth is at least partly independent of a subject’s ungrounded preferences or enjoyment.”

To see this point, first consider that people’s longings for meaning are independent of whether they find their lives enjoyable. They may have a fun life but might come to think it lacks meaning. Second, why do we seem to have an intuitive sense of meaningful and meaningless lives? Most of us would agree that certain kinds of lives are or are not meaningful. Both of the above suggest that objective values are related to meaning.

This leads Wolf to reiterate that meaningful lives are ones actively engaged in worthwhile projects. If one is engaged in life, then it has a point; looking for meaning is looking for worthwhile projects. In addition, this view shows us why some projects are thought of as meaningful and others are not. Some projects are meaningful but boring (like writing checks to the ACLU), whereas others are pleasurable (like riding roller coasters) but don’t seem to give meaning to life. In this context, Wolf notes Bernard Williams’ distinction between categorical desires, whose objects are worthwhile independent of our desires; and all other desires, whose objects’ worthiness, presumably, depends on our desires. In short, she is saying some values are objective.

To reiterate, meaningful lives link active engagement with objectively worthwhile projects. Lives lived without engagement lack meaning, even if what they are doing is meaningful since the person living such a life is bored or alienated. However, lives lived with engagement are not necessarily meaningful, if the objects of the engagement are worthless since those objects lack objective value. Wolf summaries her view as follows: “Meaning arises when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness…meaning arises when a subject discovers or develops an affinity for one or typically several of the more worthwhile things…”

Summary – Meaningful lives consist of one’s active engagement with objectively worthwhile things.

__________________________________________________________________

Susan Wolf, “Meaning in Life” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D. Klemke and Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2008), 232.

Wolf, “Meaning in Life,” 233.

Wolf, “Meaning in Life” 234-35.

December 11, 2022

A Great Blog—The Attic

[image error]

I wanted to remind my readers of a wonderful and uplifting blog called the attic. (I wrote about it just over a year ago.) Here is a brief description from the blog’s author,

Sick of the news? Come rummage in The Attic to find a kinder, cooler America. Here you’ll find common ground, not minefields. Updated weekly, The Attic features short profiles of American artists, writers, dreamers, inventors, visionaries, and more …

Time was when magazines I wrote for, Smithsonian and American Heritage, explored this space. But screens have silenced kinder, cooler Americans. The result is a nation of shrill voices. If you are world weary, skeptical, worried about this American “experiment,” join me in The Attic.

The blog is written by Bruce Watson, a regular contributor to Smithsonian, who has also written for American Heritage, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, Nautilus, Yankee, and other publications. His books include Freedom Summer, Sacco and Vanzetti, and Bread and Roses (Viking). He has also written e-biographies of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. His most recent book, nominated for a Los Angeles Times Book Award, is Light: A Radiant History from Creation to the Quantum Age (Bloomsbury).

Every post on the site is written beautifully, filled with wonderful photos, tells an American story, and can be read in just a few minutes. I have read almost all of them and enjoyed every single one. Here is a sample of recent posts:

“THE ART OF AGING” (about the artist known as Grandma Moses.)

“CROSSING THE GREAT DIVIDE” (about groups of people trying to heal a divided USA.)

“JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM” (about the fact-checkers who are standing up for truth.)

And here are a few more:

“THE WOMAN WHO WOVE THE VAXX” (about Jennifer Doudna, one of the scientists who helped create the life-saving Covid vaccines. Thank you, Dr. Doudna.)

“WALKING AMERICA WITH THE MASTER” (about Thoreau’s love of walking, one of my favorite pastimes.)

“NETWORK” — STILL MAD AS HELL” (about a great movie, and one of my favorites.)

“THE BOOK THAT LISTENED TO GIRLS” (about the voices of women which we so desperately need to hear, and a book I first read over 30 years ago.)

“LUCKIEST MAN” — THE GRACE OF LOU GEHRIG” (about Gehrig. I can still remember watching “The Pride of the Yankees” as a kid—bonus, Babe Ruth plays himself!)

“THE POET AND “THE ANSWER” (about Robinson Jeffers and his thoughts on transcending the ugliness of this world and reveling in the beauty of the universe.)

Bruce’s posts create a little bit of beauty in an oftentimes depressing world. I cannot recommend them more highly.