John G. Messerly's Blog, page 24

July 4, 2022

America Is Growing Apart, Possibly for Good

[image error]Aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, American Civil War, 1863

A reader alerted me to Ronald Brownstein’s recent article in The Atlantic, “America Is Growing Apart, Possibly for Good.” The short essay summarizes the conclusions of Michael Podhorzer, a longtime political strategist and the chair of the Analyst Institute, a collaborative of progressive groups that studies elections.

When we think about the United States, we make the essential error of imagining it as a single nation, a marbled mix of Red and Blue people … But in truth, we have never been one nation. We are more like a federated republic of two nations: Blue Nation and Red Nation. This is not a metaphor; it is a geographic and historical reality.

For Podhorzer, the differences among states in the USA today are “very similar, both geographically and culturally, to the divides between the Union and the Confederacy. And those dividing lines were largely set at the nation’s founding, when slave states and free states forged an uneasy alliance to become ‘one nation.’”

This doesn’t mean we will have another civil war, exactly but it does mean that the pressure on national cohesion will continue to increase. Like other analysts who study democracy, he views the Trump faction that now dominates the Republican Party

as the U.S. equivalent to the authoritarian parties in places such as Hungary and Venezuela. It is a multipronged, fundamentally antidemocratic movement that has built a solidifying base of institutional support through conservative media networks, evangelical churches, wealthy Republican donors, GOP elected officials, paramilitary white-nationalist groups, and a mass public following. And it is determined to impose its policy and social vision on the entire country—with or without majority support. “The structural attacks on our institutions that paved the way for Trump’s candidacy will continue to progress,” Podhorzer argues, “with or without him at the helm.”

All of this is fueling what Brownstein has called “the great divergence” now happening between red and blue states. This divergence puts enormous strain on the country’s cohesion, but this is just the beginning.

What’s becoming clearer over time is that the Trump-era GOP is hoping to use its electoral dominance of the red states, the small-state bias in the Electoral College and the Senate, and the GOP-appointed majority on the Supreme Court to impose its economic and social model on the entire nation … As measured on fronts including the January 6 insurrection, the procession of Republican 2020 election deniers running for offices that would provide them with control over the 2024 electoral machinery, and the systematic advance of a Republican agenda by the Supreme Court, the underlying political question of the 2020s remains whether majority rule—and democracy as we’ve known it—can survive this offensive.

The vast difference between red and blue states means that the 10 purple states (if you include Arizona and Georgia) decide whether red or blue values will prevail. “And that leaves the country perpetually teetering on a knife’s edge: The combined vote margin for either party across those purple states has been no greater than two percentage points in any of the past three presidential elections, he calculates.”

The increasing antagonism between the red and the blue nation is a defining characteristic of 21st-century America, whereas the middle decades of the 20th century were characterized by greater convergence.

One part of that convergence came through what legal scholars call the “rights revolution.” This refers to actions from Congress and the Supreme Court, that strengthened the floor of nationwide rights and reduced the ability of states to curtail those rights. Examples here include the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and the Supreme Court decisions striking down state bans on contraception, interracial marriage, abortion, and, later, prohibitions against same-sex intimate relations and marriage.

At the same time, “regional differences were moderated by waves of national investment, including the New Deal spending on rural electrification, the Tennessee Valley Authority, agricultural price supports, and Social Security during the 1930s, and the Great Society programs that provided federal aid for K–12 schools and higher education, as well as Medicare and Medicaid.”

The impact of these investments … helped steadily narrow the gap in per capita income between the states of the old Confederacy and the rest of the country from the 1930s until about 1980. That progress, though, stopped after 1980, and the gap remained roughly unchanged for the next three decades. Since about 2008, Podhorzer calculates, the southern states at the heart of the red nation have again fallen further behind the blue nation in per capita income.

Now it is the case that red states, as a group, fall behind blue states “on a broad range of economic and social outcomes—including economic productivity, family income, life expectancy, and “deaths of despair” from the opioid crisis and alcoholism.” Simply put blue states are benefiting more as the nation transitions to a “21st-century information economy, and red states (apart from their major metropolitan centers participating in that economy) are suffering as the powerhouse industries of the 20th century—agriculture, manufacturing, and fossil-fuel extraction—decline.”

The above is born out by the fact that

gross domestic product per person and the median household income are now both more than 25 percent greater in the blue section than in the red …The share of kids in poverty is more than 20 percent lower in the blue section than red, and the share of working households with incomes below the poverty line is nearly 40 percent lower. Health outcomes are diverging too. Gun deaths are almost twice as high per capita in the red places as in the blue, as is the maternal mortality rate. The COVID vaccination rate is about 20 percent higher in the blue section, and the per capita COVID death rate is about 20 percent higher in the red. Life expectancy is nearly three years greater in the blue (80.1 years) than the red (77.4) states.

Per capita spending on elementary and secondary education is almost 50 percent higher in the blue states compared with red. All of the blue states have expanded access to Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, while about 60 percent of the total red-nation population lives in states that have refused to do so. All of the blue states have set a minimum wage higher than the federal level of $7.25, while only about one-third of the red-state residents live in places that have done so. Right-to-work laws are common in the red states and nonexistent in the blue, with the result that the latter have a much higher share of unionized workers than the former. No state in the blue section has a law on the books banning abortion before fetal viability, while almost all of the red states are poised to restrict abortion rights … Almost all of the red states have also passed “stand your ground” laws backed by the National Rifle Association, which provide a legal defense for those who use weapons against a perceived threat, while none of the blue states have done so.

And the many socially conservative laws that red states have passed since 2021, on abortion; classroom discussions of race, gender, and sexual orientation; and LGBTQ rights, continue to widen this split. Another implication of all this is the establishment of “one-party rule in the red nation.” There we continue to see patterns from the Jim Crow era, where voting restrictions are so severe and gerrymandering so persuasive that Republicans lock in control of state legislatures.

So how will the USA function when it is essentially two different nations? Brownstein argues that history shows us two possible models for what will happen.

One possibility is the defensive one.

During the seven decades of legal Jim Crow segregation from the 1890s through the 1960s, the principal goal of the southern states at the core of red America was defensive: They worked tirelessly to prevent federal interference with state-sponsored segregation but did not seek to impose it on states outside the region.

The other possibility is that the red states will continue their offensive strategy.

in the last years before the Civil War, the South’s political orientation was offensive: Through the courts (the 1857 Dred Scott decision) and in Congress (the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854), its principal aim was to authorize the expansion of slavery into more territories and states. Rather than just protecting slavery within their borders, the Southern states sought to control federal policy to impose their vision across more of the nation, including, potentially, to the point of overriding the prohibitions against slavery in the free states.

Brownstein doubts that “the Trump-era Republicans installing the policy priorities of their preponderantly white and Christian coalition across the red states will be satisfied just setting the rules in the places now under their control.” Instead, he agrees with Podhorzer and others that

the MAGA movement’s long-term goal is to tilt the electoral rules in enough states to make winning Congress or the White House almost impossible for Democrats. Then, with support from the GOP-appointed majority on the Supreme Court, Republicans could impose red-state values and programs nationwide, even if most Americans oppose them. The “MAGA movement is not stopping at the borders of the states it already controls,” Podhorzer writes. “It seeks to conquer as much territory as possible by any means possible.”

In other words, the model of the current Trump Republican party “is more the South in 1850 than the South in 1950…” This doesn’t mean we will have another civil war like that of the 1860s but, as Brownstein soberly concludes “it does mean that the 2020s may bring the greatest threats to the country’s basic stability since those dark and tumultuous years.”

Brief Response –

Unfortunately, I agree with the above analysis. These are difficult times for those of us who are progressive and tolerant; those of us who believe in democracy and abhor fascism. I fear for my grandchildren.

Note –

Since I penned the above essay, Jonathan Weisman has published an op-ed in the NYTimes on the same theme titled “Spurred by the Supreme Court, a Nation Divides Along a Red-Blue Axis.”

June 28, 2022

Three Supreme Court decisions with long-term consequences

Scrapping abortion rights got the headlines. But don’t ignore the Court’s assault on gun regulations and the separation of church and state.

A great short essay by the conservative David Frum (George W. Bush’s speechwriter) in the Atlantic is “Roe is the New Prohibition.”

For a great analysis of recent Supreme Court rulings on abortion, guns, and public funding of Christian schools see Doug Mudar Ph.D. – “Three Supreme Court decisions with long-term consequences”

June 27, 2022

Paul Edwards, “The Meaning and Value in Life”

In “The Meaning and Value of Life” (1967) Paul Edwards (to whom we have already been introduced) notes that many religious thinkers argue that life cannot have meaning unless our lives are part of a divine plan and that at least some humans achieve eternal bliss. Non-believers are divided, some maintaining that life can have meaning without these religious provisos and others that it cannot. Edwards refers to these latter individuals as pessimists but wonders “whether pessimistic conclusions are justified if belief in God and immortality are rejected.”

Schopenhauer’s Arguments – Edwards begins by examining Schopenhauer’s claims that life is a mistake, that non-existence is preferable to existence, that happiness is fleeting and unobtainable, and that death is a final destruction: “nothing at all is worth our striving, our efforts, and struggles…All good things are vanity, the world in all its ends bankrupt, and life a business which does not cover its expenses.” Schopenhauer reinforces these conclusions by emphasizing the ephemeral and fleeting nature of pleasures and joys: “which disappear in our hands, and we afterward ask astonished where they have gone … that which in the next moment exists no more, and vanishes utterly, like a dream, can never be worth a serious effort.” Edwards thinks that this pessimism mostly reflects that Schopenhauer was a lonely, bitter, and miserable man. Still, persons of more cheerful dispositions have reached similar conclusions so we should not dismiss Schopenhauer’s too quickly.

The Pointlessness of It All – Next Edwards briefly considers the views of the famous trial attorney Clarence Darrow’s pessimism:

This weary old world goes on, begetting, with birth and with living and with death … and all of it is blind from the beginning to the end … Life is like a ship on the sea, tossed by every wave and every wind; a ship headed for no port and no harbor, with no rudder, no compass, no pilot; simply floating for a time, then lost in the waves…

Not only is life purposeless but there is death: “I love my friends … but they all must come to a tragic end.” For Darrow attachment to life makes death all the more tragic.

Next, he considers the case of Tolstoy. Perhaps no one wrote so movingly of the overwhelming fact of death and its victory over us all as Tolstoy. “Today or tomorrow … sickness and death will come to those I love or to me; nothing will remain but stench and worms. Sooner or later my affairs, whatever they may be, will be forgotten, and I shall not exist. Then why go on making any effort?” Tolstoy if you remember compared our situation to that of a man hanging on the side of a well holding on to a twig. A dragon waits below, a beast above, and mice are eating the stem of the twig. Would a small bit of honey on the twig really provide comfort? Tolstoy thinks not. Refusing to be comforted by life’s little pleasures as long as there were no answers to life’s ultimate questions, he saw but four possible answers to his condition: 1) remain ignorant; 2) admit life’s hopelessness but partake of its pleasures; 3) commit suicide; or 4) weakness, seeing the truth but clinging to life anyway. Tolstoy argues that the first solution is not available to the conscious person; the second he rejects because there are so few pleasures and to enjoy pleasures while others lack them would require “moral dullness;” he admires the third solution which is chosen by strong persons when they recognize life is no longer worth living; and the fourth solution is for those who lack the strength and rationality to end their lives. Tolstoy thought himself such a person.

Edwards wonders if those who share the pessimists’ rejection of religion might nonetheless avoid their depressing conclusions. He admits that there is much truth to the claims of the pessimists—that happiness is difficult to achieve and fleeting, that life is capricious, that death ruins our plans, that all these things cast a shadow over our lives—and we should consider these arguments well-founded. But does meaninglessness follow as Darrow and Tolstoy suggested?

Comparative Value Judgments About Life and Death – Edwards begins to answer by pointing to inconsistencies in the pessimist’s arguments. For instance, pessimists often argue that death is bad because it puts an end to life, but this amounts to saying that life does have value or else its termination would not be bad. In other words, if life had no value—say one was in a state of persistent, unending pain—then death would be good. One might say that life has value until the realization of death becomes clear, but this argument too is flawed—such a fixation on death is obsessive. Furthermore, claims that death is better than life or that it would have been better had we not been born appear incongruous. One can make comparisons between known things—that A is a better scientist or pianist than B—but if there is no afterlife as the pessimists contend, then death cannot be experienced and comparisons with life are meaningless.

The Irrelevance of the Distant Future – Edwards also attacks the claims of those who appeal to a “distant future” in which to find life’s meaning. He does not find it obvious that eternally long lives would be more meaningful than finite ones, for what is the meaning of everlasting bliss? And if future bliss needs no justification then why should bliss in this life need any?

The issue of the distant future also comes up regarding value judgments. Edwards argues that it makes sense to ask if something is valuable if we do not regard it as intrinsically valuable, or if it is being compared to some other good. But it does not make sense to ask this of something that we do consider intrinsically valuable and which is not in conflict with attaining some other good. We may meaningfully ask if the pain we experienced at the dentist is worthwhile since that is not the kind of thing we ordinarily enjoy doing, but we should not ask such questions about being happy or in love because we think such experiences are intrinsically valuable. In addition, Edwards finds concerns about the distant future irrelevant to most human concerns—we are typically concerned with the present or near future. Even if you and the dentist are both dead in a hundred years that does not mean that your efforts now are worthless.

The Vanished Past – Some claim that life’s worthlessness derives from the fact that the past is gone forever, which implies that the past is as if it had never been. Others claim that the present’s trivialities are more important than the past’s most important events. To the first claim, Edwards replies that if only the present matters then past sorrows, as well as past pleasures, do not matter. To the second claim, he points out that this is simply a value judgment about which he and others differ. While the pessimist might lament the passing years and the non-existence of the past, the optimist may take pride in realities actualized as opposed to potentialities unfulfilled. Still, Edwards admits that there is a sense in which the past does seem less valuable than the present, as evidenced by how little consolation to the sick or aged would be the fact that they used to be healthy. Thus the issue of the relative value of past and present is debatable.

To recap Edwards’ main points: 1) comparative judgments about life versus death are unintelligible; 2) the experience of a distant future will not necessarily make life worthwhile; 3) it makes no sense to ask if intrinsically valuable things are really valuable; and 4) the vanished past does not say much about life’s meaning. In sum, the pessimists have not established their arguments convincingly.

The Meanings of the “Meaning of Life” – If the pessimistic conclusions do not necessarily follow from the rejection of gods and immortality is there a reason for optimism? Can there be meaning without gods or immortality? To answer these questions Edwards appeals to Baier’s distinction between: 1) whether we have a role in a great drama or whether there is an objective meaning to the whole thing—what Edwards calls meaning in the cosmic sense; and 2) whether or not our lives have meaning from within or subjectively—what Edwards calls the terrestrial sense. It is easy to claim that someone’s life has meaning for them, but harder to defend the claim that life has meaning in the cosmic sense. It is important to note that to say one’s life has meaning in the terrestrial sense does not imply that such a life was good. A person might achieve the goals of their life, to be a good murderer for example, but it is easy to see that such a life is not good.

While it is easy enough to reject cosmic meaning—the pessimist’s view—it does not follow that rejection of cosmic meaning eliminates terrestrial meaning. It is perfectly coherent to proclaim that there is no cosmic plan but that one nevertheless finds their terrestrial life meaningful. Many individuals have achieved such meaning without supernatural beliefs. Moreover, the existence of cosmic meaning hardly guarantees meaning in the terrestrial sense. Even if there is an ultimate plan for my life I would need to know it, believe in it, and work toward its realization.

Is Human Life Ever Worthwhile? – Turning to the question of whether life is ever worthwhile, Edwards wonders what makes individuals ask this question and why they might answer it negatively. To say that life is worthwhile for a person implies that they have some goals and the possibility of attaining them. While this account is similar to the notion of meaning in the terrestrial sense, it differs because worthiness implies value whereas terrestrial meaning does not. In other words, terrestrial meaning implies only subjective value, whereas the notion of a worthwhile life implies the existence of objective values. In the latter case, we have goals, the possibility of their attainment, and the notion that those goals are really valuable. But Edwards claims that he doesn’t need objective values to determine the worthiness of a life, inasmuch as even the subjectivist will allow some distinction between good and bad conduct. He bases his argument on the agreement of “rational and sympathetic human beings.”

Still, the pessimists are dissatisfied. They grant that person’s lives may have meaning in the subjective sense but claim this is not enough “because our lives are not followed by eternal bliss.” Edwards counters that pessimists have unrealistic standards of meaning that go beyond those of ordinary persons—who are content with subjective meaning. According to the standards of pessimists, life is not worthwhile because it is not followed by eternal bliss, but this does not imply that it is not worthwhile by other less demanding standards. And why should we accept the special standards of the pessimist? In fact, Edwards notes that ordinary standards of living such as achieving our goals do something that the pessimists’ standards do not—they guide our lives.

Moreover, there are a number of questions we might ask the pessimist. Why does eternal bliss bestow meaning on life, while bliss in this life does not? Why should we abandon our ordinary standards of meaning for the special standards of the pessimists? This latter question is particularly difficult for the pessimist to answer—after all, nothing is of value to the pessimist. Still, pessimists usually do not commit suicide, suggesting that they believe there is some reason for living. And they often have principles and make value judgments as if something does matter. Thus there is something disingenuous about their position.

Is the Universe Better with Human Life Than Without It? – All of this leads to the ultimate question: is the universe better with or without human life in it? Edwards thinks that without an affirmative response to this question, no affirmative response can be given to the meaning of life question. He quotes the German phenomenologist, Hans Reiner, in this regard: “Our search for the meaning of our lives … is identical with the search for a logically compelling reason why it is better for us to exist than not to exist. … whether it is better that mankind should exist than that there should be a world without any human life.” A possible answer to this question appeals to the intrinsic meaning of the morally good a pre-condition which demands the existence of moral agents and a universe. In that case, it is better that the universe and humans exist so that moral good can exist. Of course, this claim is open to the objection that a universe and moral agents introduce physical and moral evil which counterbalances the good. In that case, whether it is better that the universe exists or not would depend on whether more good than evil exists.

Why the Pessimist Cannot be Answered – The upshot of all this is that one cannot satisfactorily answer the pessimist. Why? Because questions such as whether life is better than death or whether the universe would be better if it had not existed have no clear meaning. Is it better for humans and the universe to exist than not? Philosophers have answered the question variously: Schopenhauer answered in the negative, Spinoza in the positive. But Edwards concludes that there are no knock-down arguments either way. It is simply impossible to prove that “coffee with cream is better than black coffee,” or “that love is better than hate.”

Summary – Human life can have subjective, terrestrial meaning, and some lives are worthwhile as long as standards of meaning are not set too high. But pessimists ultimately cannot be answered if we need to show them that human existence is better than non-existence. We cannot know, all things considered if it is good that life exists.

______________________________________________________________________

Paul Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E. D. Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford University Press 2008), 115.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 118.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 128.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 130.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 133.

Paul Edward, “The Meaning and Value in Life”

In “The Meaning and Value of Life” (1967) Paul Edwards (to whom we have already been introduced) notes that many religious thinkers argue that life cannot have meaning unless our lives are part of a divine plan and that at least some humans achieve eternal bliss. Non-believers are divided, some maintaining that life can have meaning without these religious provisos and others that it cannot. Edwards refers to these latter individuals as pessimists but wonders “whether pessimistic conclusions are justified if belief in God and immortality are rejected.”

Schopenhauer’s Arguments – Edwards begins by examining Schopenhauer’s claims that life is a mistake, that non-existence is preferable to existence, that happiness is fleeting and unobtainable, and that death is a final destruction: “nothing at all is worth our striving, our efforts, and struggles…All good things are vanity, the world in all its ends bankrupt, and life a business which does not cover its expenses.” Schopenhauer reinforces these conclusions by emphasizing the ephemeral and fleeting nature of pleasures and joys: “which disappear in our hands, and we afterward ask astonished where they have gone … that which in the next moment exists no more, and vanishes utterly, like a dream, can never be worth a serious effort.” Edwards thinks that this pessimism mostly reflects that Schopenhauer was a lonely, bitter, and miserable man. Still, persons of more cheerful dispositions have reached similar conclusions so we should not dismiss Schopenhauer’s too quickly.

The Pointlessness of It All – Next Edwards briefly considers the views of the famous trial attorney Clarence Darrow’s pessimism:

This weary old world goes on, begetting, with birth and with living and with death … and all of it is blind from the beginning to the end … Life is like a ship on the sea, tossed by every wave and every wind; a ship headed for no port and no harbor, with no rudder, no compass, no pilot; simply floating for a time, then lost in the waves…

Not only is life purposeless but there is death: “I love my friends … but they all must come to a tragic end.” For Darrow attachment to life makes death all the more tragic.

Next, he considers the case of Tolstoy. Perhaps no one wrote so movingly of the overwhelming fact of death and its victory over us all as Tolstoy. “Today or tomorrow … sickness and death will come to those I love or to me; nothing will remain but stench and worms. Sooner or later my affairs, whatever they may be, will be forgotten, and I shall not exist. Then why go on making any effort?” Tolstoy if you remember compared our situation to that of a man hanging on the side of a well holding on to a twig. A dragon waits below, a beast above, and mice are eating the stem of the twig. Would a small bit of honey on the twig really provide comfort? Tolstoy thinks not. Refusing to be comforted by life’s little pleasures as long as there were no answers to life’s ultimate questions, he saw but four possible answers to his condition: 1) remain ignorant; 2) admit life’s hopelessness but partake of its pleasures; 3) commit suicide; or 4) weakness, seeing the truth but clinging to life anyway. Tolstoy argues that the first solution is not available to the conscious person; the second he rejects because there are so few pleasures and to enjoy pleasures while others lack them would require “moral dullness;” he admires the third solution which is chosen by strong persons when they recognize life is no longer worth living; and the fourth solution is for those who lack the strength and rationality to end their lives. Tolstoy thought himself such a person.

Edwards wonders if those who share the pessimists’ rejection of religion might nonetheless avoid their depressing conclusions. He admits that there is much truth to the claims of the pessimists—that happiness is difficult to achieve and fleeting, that life is capricious, that death ruins our plans, that all these things cast a shadow over our lives—and we should consider these arguments well-founded. But does meaninglessness follow as Darrow and Tolstoy suggested?

Comparative Value Judgments About Life and Death – Edwards begins to answer by pointing to inconsistencies in the pessimist’s arguments. For instance, pessimists often argue that death is bad because it puts an end to life, but this amounts to saying that life does have value or else its termination would not be bad. In other words, if life had no value—say one was in a state of persistent, unending pain—then death would be good. One might say that life has value until the realization of death becomes clear, but this argument too is flawed—such a fixation on death is obsessive. Furthermore, claims that death is better than life or that it would have been better had we not been born appear incongruous. One can make comparisons between known things—that A is a better scientist or pianist than B—but if there is no afterlife as the pessimists contend, then death cannot be experienced and comparisons with life are meaningless.

The Irrelevance of the Distant Future – Edwards also attacks the claims of those who appeal to a “distant future” in which to find life’s meaning. He does not find it obvious that eternally long lives would be more meaningful than finite ones, for what is the meaning of everlasting bliss? And if future bliss needs no justification then why should bliss in this life need any?

The issue of the distant future also comes up regarding value judgments. Edwards argues that it makes sense to ask if something is valuable if we do not regard it as intrinsically valuable, or if it is being compared to some other good. But it does not make sense to ask this of something that we do consider intrinsically valuable and which is not in conflict with attaining some other good. We may meaningfully ask if the pain we experienced at the dentist is worthwhile since that is not the kind of thing we ordinarily enjoy doing, but we should not ask such questions about being happy or in love because we think such experiences are intrinsically valuable. In addition, Edwards finds concerns about the distant future irrelevant to most human concerns—we are typically concerned with the present or near future. Even if you and the dentist are both dead in a hundred years that does not mean that your efforts now are worthless.

The Vanished Past – Some claim that life’s worthlessness derives from the fact that the past is gone forever, which implies that the past is as if it had never been. Others claim that the present’s trivialities are more important than the past’s most important events. To the first claim, Edwards replies that if only the present matters then past sorrows, as well as past pleasures, do not matter. To the second claim, he points out that this is simply a value judgment about which he and others differ. While the pessimist might lament the passing years and the non-existence of the past, the optimist may take pride in realities actualized as opposed to potentialities unfulfilled. Still, Edwards admits that there is a sense in which the past does seem less valuable than the present, as evidenced by how little consolation to the sick or aged would be the fact that they used to be healthy. Thus the issue of the relative value of past and present is debatable.

To recap Edwards’ main points: 1) comparative judgments about life versus death are unintelligible; 2) the experience of a distant future will not necessarily make life worthwhile; 3) it makes no sense to ask if intrinsically valuable things are really valuable; and 4) the vanished past does not say much about life’s meaning. In sum, the pessimists have not established their arguments convincingly.

The Meanings of the “Meaning of Life” – If the pessimistic conclusions do not necessarily follow from the rejection of gods and immortality is there a reason for optimism? Can there be meaning without gods or immortality? To answer these questions Edwards appeals to Baier’s distinction between: 1) whether we have a role in a great drama or whether there is an objective meaning to the whole thing—what Edwards calls meaning in the cosmic sense; and 2) whether or not our lives have meaning from within or subjectively—what Edwards calls the terrestrial sense. It is easy to claim that someone’s life has meaning for them, but harder to defend the claim that life has meaning in the cosmic sense. It is important to note that to say one’s life has meaning in the terrestrial sense does not imply that such a life was good. A person might achieve the goals of their life, to be a good murderer for example, but it is easy to see that such a life is not good.

While it is easy enough to reject cosmic meaning—the pessimist’s view—it does not follow that rejection of cosmic meaning eliminates terrestrial meaning. It is perfectly coherent to proclaim that there is no cosmic plan but that one nevertheless finds their terrestrial life meaningful. Many individuals have achieved such meaning without supernatural beliefs. Moreover, the existence of cosmic meaning hardly guarantees meaning in the terrestrial sense. Even if there is an ultimate plan for my life I would need to know it, believe in it, and work toward its realization.

Is Human Life Ever Worthwhile? – Turning to the question of whether life is ever worthwhile, Edwards wonders what makes individuals ask this question and why they might answer it negatively. To say that life is worthwhile for a person implies that they have some goals and the possibility of attaining them. While this account is similar to the notion of meaning in the terrestrial sense, it differs because worthiness implies value whereas terrestrial meaning does not. In other words, terrestrial meaning implies only subjective value, whereas the notion of a worthwhile life implies the existence of objective values. In the latter case, we have goals, the possibility of their attainment, and the notion that those goals are really valuable. But Edwards claims that he doesn’t need objective values to determine the worthiness of a life, inasmuch as even the subjectivist will allow some distinction between good and bad conduct. He bases his argument on the agreement of “rational and sympathetic human beings.”

Still, the pessimists are dissatisfied. They grant that person’s lives may have meaning in the subjective sense but claim this is not enough “because our lives are not followed by eternal bliss.” Edwards counters that pessimists have unrealistic standards of meaning that go beyond those of ordinary persons—who are content with subjective meaning. According to the standards of pessimists, life is not worthwhile because it is not followed by eternal bliss, but this does not imply that it is not worthwhile by other less demanding standards. And why should we accept the special standards of the pessimist? In fact, Edwards notes that ordinary standards of living such as achieving our goals do something that the pessimists’ standards do not—they guide our lives.

Moreover, there are a number of questions we might ask the pessimist. Why does eternal bliss bestow meaning on life, while bliss in this life does not? Why should we abandon our ordinary standards of meaning for the special standards of the pessimists? This latter question is particularly difficult for the pessimist to answer—after all, nothing is of value to the pessimist. Still, pessimists usually do not commit suicide, suggesting that they believe there is some reason for living. And they often have principles and make value judgments as if something does matter. Thus there is something disingenuous about their position.

Is the Universe Better with Human Life Than Without It? – All of this leads to the ultimate question: is the universe better with or without human life in it? Edwards thinks that without an affirmative response to this question, no affirmative response can be given to the meaning of life question. He quotes the German phenomenologist, Hans Reiner, in this regard: “Our search for the meaning of our lives … is identical with the search for a logically compelling reason why it is better for us to exist than not to exist. … whether it is better that mankind should exist than that there should be a world without any human life.” A possible answer to this question appeals to the intrinsic meaning of the morally good a pre-condition which demands the existence of moral agents and a universe. In that case, it is better that the universe and humans exist so that moral good can exist. Of course, this claim is open to the objection that a universe and moral agents introduce physical and moral evil which counterbalances the good. In that case, whether it is better that the universe exists or not would depend on whether more good than evil exists.

Why the Pessimist Cannot be Answered – The upshot of all this is that one cannot satisfactorily answer the pessimist. Why? Because questions such as whether life is better than death or whether the universe would be better if it had not existed have no clear meaning. Is it better for humans and the universe to exist than not? Philosophers have answered the question variously: Schopenhauer answered in the negative, Spinoza in the positive. But Edwards concludes that there are no knock-down arguments either way. It is simply impossible to prove that “coffee with cream is better than black coffee,” or “that love is better than hate.”

Summary – Human life can have subjective, terrestrial meaning, and some lives are worthwhile as long as standards of meaning are not set too high. But pessimists ultimately cannot be answered if we need to show them that human existence is better than non-existence. We cannot know, all things considered if it is good that life exists.

______________________________________________________________________

Paul Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E. D. Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford University Press 2008), 115.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 117.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 118.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 128.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 130.

Edwards, “The Meaning and Value of Life,” 133.

June 24, 2022

Breaking news – Illegal for women to end unwanted pregnancy – Religious fanaticism prevails!

The USA now joins a list of countries that includes: Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Iraq, Kiribati, Libya, Madagascar, Nicaragua, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Philippines, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, , Syria, Tonga, Tuvalu, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

Basically, the above countries are characterized by Christian or Muslim fanaticism, are very poor, or both. The USA also leaves the list of virtually all the countries ranked objectively as the best places to live—Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, etc. Well, you get the idea. We join the backward theocratic backward countries and part ways with the best ones. For more see

June 20, 2022

Klemke “Living Without Appeal”

E.D. Klemke (1926-2000) taught for more than twenty years at Iowa State University. He was a prolific editor and one of his best known collections is The Meaning of Life: A Reader, first published in 1981. The following summary is of his 1981 essay: “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life.” I find it one of the most profound pieces in the literature.

Klemke begins by stating that the topics of interest to professional philosophers are abstruse and esoteric. This is in large part justified as we need to be careful and precise in our thinking if we are to make progress in solving problems; but there are times when a philosopher ought to “speak as a man among other men.” In short a philosopher must bring his analytical tools to a problem such as the meaning of life. Klemke argues that the essence of the problem for him was captured by Camus in the phrase: “Knowing whether or not one can live without appeal is all that interests me.”[ii]

Many writers in the late 20th century had a negative view of civilization characterized by the notion that society was in decay. While the problem has been expressed variously, the basic theme was that some ultimate, transcendent principle or reality was lacking. This transcendent ultimate (TU), whatever it may be, is what gives meaning to life. Those who reject this TU are left to accept meaninglessness or exalt natural reality; but either way, this hope is futile because without this TU there is no meaning.

Klemke calls this view transcendentalism, and it is composed of three theses: 1) a TU exists and one can have a relationship with it; 2) without a TU (or faith in one) there is no meaning to life; and 3) without meaning human life is worthless. Klemke comments upon each in turn.

1. Regarding the first thesis, Klemke assumes that believers are making a cognitive claim when they say that a TU exists, that it exists in reality. But neither religious texts, unusual persons in history nor the fact that large numbers of persons believe this provides evidence for a TU—and the traditional arguments (for the existence of God for example) are not thought convincing by most experts. Moreover, religious experience is not convincing since the source of the experience is always in doubt. In fact, there is no evidence for the existence of a TU, and those who think it a matter of faith agree; there is thus no reason to accept the claim that a TU exists. The believer could counter that one should employ faith to which Klemke responds: a) we normally think of faith as implying reasons and evidence; and b) even if faith is something different in this context Klemke claims he does not need it. To this the transcendentalist responds that such faith is needed for there to be a meaning of life which leads to the second thesis:

2. The transcendentalist claims that without faith in a TU there is no meaning, purpose, or integration.

a. Klemke firsts considers whether meaning may only exist if a TU exists. Here one might mean subjective or objective meaning. If we are referring to objective meaning Klemke replies that: i) there is nothing inconsistent about holding that objective meaning exists without a TU; and ii) there is no evidence that objective meaning exists. We find many things when we look at the universe, stars in motion for example, but meaning is not one of them. We do not discover values we create, invent, or impose them on the world. Thus there is no more reason to believe in the existence of objective meaning than there is to believe in the reality of a TU.

i. The transcendentalist might reply by agreeing that there is no objective meaning in the universe but argue that subjective meaning is not possible without a TU. Klemke replies: 1) this is false, there is subjective meaning; and 2) what the transcendentalists are talking about is not subjective meaning but rather objective meaning since it relies on a TU.

ii. The transcendentalist might reply instead that one cannot find meaning unless one has faith in a TU. Klemke replies: 1) this is false; and 2) even if it were true he would reject such faith because: “If I am to find any meaning in life, I must attempt to find it without the aid of crutches, illusory hopes, and incredulous beliefs and aspirations.” Klemke admits he may not find meaning, but he must try to find it on his own in something comprehensible to humans, not in some incomprehensible mystery. He simply cannot rationally accept meaning connected with things for which there is no evidence and, if this makes him less happy, then so be it. In this context he quotes George Bernard Shaw: “The fact that a believer is happier than a skeptic is no more to the point than the fact that a drunken man is happier than a sober one. The happiness of credulity is a cheap and dangerous quality.”

b. Klemke next considers the claim that without the TU life is purposeless. He replies that objective purpose is not found in the universe anymore than objective meaning is and hence all of his previous criticisms regarding objective meaning apply to the notion of objective purpose.

c. Klemke now turns to the idea that there is no integration with a TU. He replies:

i. This is false; many persons are psychologically integrated or healthy without supernaturalism.

ii. Perhaps the believer means metaphysical rather than psychological integration—the idea is that humans are at home in the universe. He answers that he does not understand what this is or if anyone has achieved it, assuming it is real. Some may have claimed to be one with the universe, or something like that, but that is a subjective experience only and not evidence for any objective claim about reality. But even if there are such experiences only a few seem to have had them, hence the need for faith; so faith does not imply integration and integration does not need faith. Finally, even if faith does achieve integration for some, it does not work for Klemke since the TU is incomprehensible. So how then does Klemke live without appeal?

3. He now turns to the third thesis that without meaning (which one cannot have without the existence of or belief in a TU) life is worthless. It is true that life has no objective meaning—which can only be derived from the nature of the universe or some external agency—but that does not mean life is subjectively worthless. Klemke argues that even if there were an objective meaning “It would not be mine.” In fact, he is glad there is not such a meaning since this allows him the freedom to create his own meaning. Some may find life worthless if they must create their own meaning, especially if they lack a rich interior life in which to find the meaning absent in the world. Klemke says that: “I have found subjective meaning through such things as knowledge, art, love, and work.” There is no objective meaning but this opens us the possibility of endowing meaning onto things through my consciousness of them—rocks become mountains to climb, strings make music, symbols make logic, wood makes treasures. “Thus there is a sense in which it is true … that everything begins with my consciousness, and nothing has any worth except through my consciousness.”

Klemke concludes by revisiting the story told by Tolstoy of the man hanging on to a plant in a pit, with dragon below and mice eating the roots of the plant, yet unable to enjoy the beauty and fragrance of a rose. Yes, we all hang by a thread over the abyss of death, but still we possess the ability to give meaning to our lives. Klemke says that if he cannot do this—find subjective meaning against the backdrop of objective meaninglessness—then he ought to curse life. But if he can give life subjective meaning to life despite the inevitability of death, if he can respond to roses, philosophical arguments, music, and human touch, “if I can so respond and can thereby transform an external and fatal event into a moment of conscious insight and significance, then I shall go down without hope or appeal yet passionately triumphant and with joy.”

Summary – The meaning of life is found in the unique way consciousness projects meaning onto an otherwise tragic reality.

_______________________________________________________________

E. D. Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 184-195.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 185.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 185.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 192.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 193.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 193-4.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 194.

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 194.

June 16, 2022

Emily Brontë’s Poem “Life”

[image error]

A portrait of Emily Brontë made by her brother, Branwell Brontë

Emily Jane Brontë (1818 – 1848) was an English novelist and poet who is best known for her only novel Wuthering Heights, a classic of English literature. Her sister Charlotte Brontë (1816 – 1855) was the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and is best known for the novel Jane Eyre, another classic of English literature. Anne Brontë (1820 –1849) was the youngest member of the Brontë literary family. Her best-known novels are Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

(Left to right – Anne, Emily, and Charlotte. Their brother Branwell, is the shadowy figure in the middle. He apparently painted himself out of the portrait.)

Together the sisters also published a volume of poetry called Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell . (The pen names of the sisters.) In that volume Emily penned a short poem titled “Life.” She was in her twenties when it was written, and some might think it juvenile, naive, childish or overly optimistic.

. (The pen names of the sisters.) In that volume Emily penned a short poem titled “Life.” She was in her twenties when it was written, and some might think it juvenile, naive, childish or overly optimistic.

But to me it is simple yet unpretentious, both hopeful and reassuring, displaying a pleasant youthful innocence that so many cynics have forgotten. I like the poem. And it rhymes!

LIFE, believe, is not a dream

So dark as sages say;

Oft a little morning rain

Foretells a pleasant day.

Sometimes there are clouds of gloom,

But these are transient all;

If the shower will make the roses bloom,

O why lament its fall?

Rapidly, merrily,

Life’s sunny hours flit by,

Gratefully, cheerily,

Enjoy them as they fly!

What though Death at times steps in

And calls our Best away?

What though sorrow seems to win,

O’er hope, a heavy sway?

Yet hope again elastic springs,

Unconquered, though she fell;

Still buoyant are her golden wings,

Still strong to bear us well.

Manfully, fearlessly,

The day of trial bear,

For gloriously, victoriously,

Can courage quell despair!

June 13, 2022

On Tyranny – Timothy Snyder

[image error]

© Darrell Arnold– (Reprinted with Permission)

http://darrellarnold.com/2018/07/16/o...

In bite-sized chunks of two to eight (short) pages Timothy Snyder, the Levin Professor of History at Yale University, offers a practical guide to understanding and possibly averting tyranny. [In his new book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century.]

At 126 pages, this small paperback is a great, quick read that offers lessons Snyder has accumulated over years of studying tyrannies around the world. His advice, accompanied by anecdotal stories from authoritarian regimes in twenty chapters, includes: Defend institutions, Remember Professional ethics, Believe in truth, Establish a private life, Be a patriot.

In Chapter 4, “Take responsibility for the face of the world,” Snyder asserts that “life is political”: “the minor choices we make are themselves a kind of vote” (33). In everyday life, then, we should be attentive to our effect on the social and political world around us. In Hitler’s Germany, for example, small delinquencies in the everyday cascaded into increasingly larger ones: those who were able to be stamped as “pigs” were easier to later boycott because they were Jewish; and they were so much the easier to target more egregiously later. After first dehumanizing them in speech and with symbols, it was later possible to completely dominate them.

In Chapter five, “Remember professional ethics,” Snyder mentions both how legal and medical professionals came to the service of the Nazi regime. Professional lawyers helped twist the law to the Nazi’s perverse ends. Medical professionals proved quite willing to participate in ungodly experiments with Jews to advance medical knowledge. Collectives of professionals who are committed to the ethical codes of their professions can offer some resistance to dehumanizing practices supported by a government. As Snyder notes: “Professional ethics must guide us precisely when we are told that the situation is exceptional” (41).

In Chapter eight, “Stand Out,” Snyder reminds us of great individuals throughout history, like Rosa Parks, who were not afraid to stand out and follow their consciences in the face of opposing political forces and who set positive examples for the struggle against domination. In various historical examples, we see it is all too easy to accommodate those who dominate. However, Winston Churchill in 1940 was another counter-example, as he entered into war to help Poland, which was largely seen by many others as a lost cause. As Snyder writes: “he himself helped the British to define themselves as a proud people who would calmly resist evil…. Churchill did what others had not done. Rather than concede in advance, he forced Hitler to change his plans” (54ff.).

Chapter 10, entitled “Believe in Truth,” begins with the prescient statement: “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights” (65). Once truth is disarmed, and people simply reject it as the adjudicating criteria for belief, politics can quickly descend into spectacle. Hostility toward verification dominates. “Shamanistic incantations,” which Victor Klemperer described as “endless repetition” of some key phrases, takes over: Think of “lock her up” or “Build that wall.” Magical thinking also comes to dominate, accompanying the confused view that one particular political leader alone can solve the nation’s ills. As in the German example, people come to accept that one just needs faith in the “Fuehrer.” Our post-truth culture increases our vulnerability to this. In Snyder’s words: “Post-truth is pre-fascism” (71)

To break the spell of magical thinking and incantation, it is important to “investigate” (Chapter 11). Clearly, much of the information that we encounter every day is false. Some of it is purposefully meant to sew confusion. So it is important to learn to think critically about sources of information and to pursue a correct understanding of the world. As Vaclav Havel had written, “If the main pillar of the system is living a lie, then it is not surprising that the fundamental threat to it is living in truth” (78).

In “Practice corporal politics” and “Establish a private life” (Chapters 13 and 14), Snyder highlights the need for contact with people in one’s private life, partially in civil society (churches, clubs, organizations). Since “tyrants seek the hook on which to hang you,” he also advises “try not to have hooks.” Secure private information, for example, on your computer. But also publicly we can join groups that preserve human rights (91). This is related to Chapter 15, “Contribute to good causes”: The contribution can be in time or money, but it is a form of active engagement in shaping the world in accord with our own values and views.

In Chapter 16, “Learn from peers in other countries,” Snyder urges us to not only learn from others but to make friends with those in other countries. And in case the tyranny comes, “Make sure you and your family have passports” (95).

In “Be Calm When the Unthinkable Comes,” Chapter 18, we are urged to consider that demagogues often exploit crises to implement Martial law. In the search for safety, it is precisely in times of crisis that people are often more willing to compromise civil liberties and to allow changes in the constitutional order. Realize this, and counter it if it begins to occur. Understand the difference between patriotism and nationalism. In “Be Patriotic,” Chapter 19, Snyder encourages us to serve the ideals of our rights-based democracy, not to be victims of an authoritarian politics carried out by nationalists who are often completely out of sync with the ideals of the nation. Chapter 20 enjoins “Be as courageous as you can”: “If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny” (115).

Snyder finishes the book with a short epilogue contrasting two views of politics that he views as anti-historical, the “politics of inevitability” with the “politics of eternity.” Inevitability politicians work with a teleological view of history in which the course of history is maintained to be known in advance. It is anti-historical insofar as such a view presumes that there is no real freedom to escape the final end of history. Eternity politicians are anti-historical in another way. They focus on a past, but as an ideal type, not one comprised of real facts. So, eternity politicians refer to the soul of a country, pure, and often under siege by external forces. In contrast, Snyder sees what we might call a politics of freedom under which “history permits us to be responsible: not for everything, but for something” (125).

This typology is developed further in Snyder’s “The Road to Unfreedom.” Regardless of whether one finds the typology ultimately compelling or accepts Snyder’s apparent moderate liberalism, one may still admire Snyder’s attempt to highlight the importance of human freedom. Those attracted to Snyder’s book, which I hope will be many, are likely to agree with his appeals that we ought to “begin to make history” (126). Otherwise, various authoritarians surely will do it for us.

Since Snyder wrote his book, the possibilities of an increase in authoritarianism, unfortunately, do not appear to be abating. Rather, there increasingly appear to be very good reasons to heed Snyder’s practical suggestions for a politics of resistance.

June 9, 2022

Philosophy as Wondering

I have taught out of several hundred philosophy books in my college teaching career. One textbook, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, had a prelude with a futuristic photo of a spaceship, missile launching, or futuristic house (depending on the edition) along with a few words from the author. It set the tone for the exploration upon which my students and I were about to embark.

Those words were simple, although philosophy is generally a difficult, esoteric pursuit. They were written by a professor who wanted to communicate with his heart, not impress students with his intellect. I think his words communicated the value of philosophy, especially for the uninitiated. Here is what he wrote:

The following pages may

lead you to wonder.

That’s really what philosophy

is—wondering.

To philosophize

is to wonder about life—

about right and wrong,

love and loneliness, war and death.

It is to wonder creatively

about freedom, truth, beauty, time

and a thousand other things.

To philosophize is

to explore life.

It especially means breaking free

to ask questions.

It means resisting

easy answers.

To philosophize

is to seek in oneself

the courage to ask

painful questions.

But if, by chance,

you have already asked

all your questions

and found all the answers—

if you’re sure you know

right from wrong,

and whether God exists,

and what justice means,

and why we mortals fear and hate and pray—

if indeed you have completed your wondering

about freedom and love and loneliness

and those thousand other things,

then the following pages

will waste your time.

Philosophy is for those

who are willing to be disturbed

with a creative disturbance.

Philosophy is for those

who still have the capacity

for wonder.

June 6, 2022

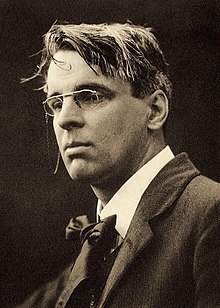

Summary of “The Lake Isle of Innisfree”

Innisfree sits in the middle of Lough Gill, a lake in County Sligo in northwest Ireland.

Innisfree sits in the middle of Lough Gill, a lake in County Sligo in northwest Ireland.

“The Lake Isle of Innisfree”

by William Butler Yeats

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee;

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

What I like about this beautiful poem is its simplicity and clarity. The first stanzas tell you he is going to an island, and he can already imagine himself there. Next, he tells you about his physical needs for food and shelter. The second stanza turns to his spiritual needs. What he needs most is peace. The final stanza signals his intent to leave but, surprisingly, he continues to hear the sounds of the island when he’s in the city. Now we understand. Innisfree is an internal place that we find in our hearts. Yeats wants to be somewhere better than where he is. What a wonderful poem; it is worth the memorizing.