John G. Messerly's Blog, page 135

October 7, 2014

My Friend’s Mother is Dying

Dedicated to my good friend, Professor Louis de Saussure

Long ago we befriended each other, and our lives were both enriched. Thank you Louis.

My good friend emailed me today concerning the impending death of his dear mother. Faced with the choice of palliative care, or keeping his mother in her own home with the doctors and nurses close by, my friend choose to have her stay in his and his wife’s bed, while they sleep in their living room. Here is an excerpt of my response to his letter:

Dear Louis:

I am so sorry to hear about your mother. I wish there was something profound I could say, but at this moment words are inadequate. All that I can say is that you are an extraordinary son—caring for your mother in your home, in her final hours. I know that your mother appreciates this more than her own now feeble voice can convey.

Believe me when she looks at your face with her now aged one, she sees a small boy from more than forty years ago who, with her help, grew to be a wonderful man. She remembers holding you when you were an infant, your life totally dependent on her love and care; she remembers taking you to school for the first time; she remembers you learning to read and write, to ski and ride a bike. And she remembers you becoming independent of her, growing up, and marrying your beautiful wife Marina.

When she hears your voice she takes pride in knowing that you are a wonderful husband, father, and scholar. When she hears Marina’s voice, she is happy to know that you have a wonderful companion in life, without which life is so lonely. Even to the extent she cannot see and hear, her mind races with a thousand memories that form the narrative of a life well-lived. The flickering flame of a consciousness that will soon go out, but which has been lit deep within you. And when she sees and hears her most beautiful grandchildren, she finds comfort in knowing that life and love go on, and that her desire for a beautiful and just world will continue. She knows the flame of life has been transferred from her candle to yours, and from yours to your childrens. She knows that life will be hard, but that it is still worth it. She knows that her son and his family will still stand when she falls, and that the longings of her own heart are imbedded in theirs. In all this, hopefully she finds peace. And she does not fear death, for like Bertrand Russell see knows:

The best way to overcome [the fear of death] is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The [people] who, in old age, can see [their] life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things [they] care for will continue.

I don’t know if this is comforting to you or your mother. But I know there is some truth in Russell’s words, which were echoed, in a different form, in the most moving description of life and death that I have encountered in my intellectual journey—the words of the philosopher and historian Will Durant. I quote them in full with the hope they provide comfort, while at the same time remaining true to what we know of the human condition.

Here is an old person on the bed of death, harassed with helpless friends and wailing relatives. What a terrible sight it is – this thin frame with loosened and cracking flesh, this toothless mouth in a bloodless face, this tongue that cannot speak, these eyes that cannot see! To this pass youth has come, after all its hopes and trials; to this pass middle age, after all its torment and its toil. To this pass health and strength and joyous rivalry; this arm once struck great blows and fought for victory in virile games. To this pass knowledge, science, wisdom: for seventy years this person with pain and effort gathered knowledge; their brain became the storehouse of a varied experience, the center of a thousand subtleties of thought and deed; their heart through suffering learned gentleness as their mind learned understanding; seventy years they grew from an animal into a person capable of seeking truth and creating beauty. But death is upon them, poisoning them, choking them, congealing blood, gripping their heart, bursting their brain, rattling in their throat. Death wins

Outside on the green boughs birds twitter, and Chantecler sings his hymn to the sun. Light streams across the fields; buds open and stalks confidently lift their heads; the sap mounts in the trees. Here are children: what is it that makes them so joyous, running madly over the dew-wet grass, laughing, calling, pursuing, eluding, panting for breath, inexhaustible? What energy, what spirit and happiness! What do they care about death? They will learn and grow and love and struggle and create, and lift life up one little notch, perhaps, before they die. And when they pass they will cheat death with children, with parental care that will make their offspring finer than themselves. There in the garden’s twilight lovers pass, thinking themselves unseen; their quiet words mingle with the murmur of insects calling to their mates; the ancient hunger speaks through eager and through lowered eyes, and a noble madness courses through clasped hands and touching lips. Life wins.

With my very best wishes for your future health and happiness, and with love to all your family, I remain, as always,

Your friend John

1.

October 6, 2014

The Chair of The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space, and Technology is a Christian Scientist!

My Encounter with The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

Last week I wrote a post entitled “Black Holes and Political Ignorance.” In it I quoted Representative Lamar Smith (R-Texas) who, reacting to the recent news that black holes might not exist, said: ““Going forward, members of the House Science Committee will do our best to avoid listening to scientists.” A footnoted disclaimer appeared at the bottom of the page informing readers that the quote was taken from a satirical piece and that the representative had not said this.

The same day I received an email from Zachary Kurz, the Communications Director for the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology of the U.S. House of Representatives. Mr. Kurz had become aware of my piece, which had been reprinted in Humanity+ Magazine, where the disclaimer was inadvertently omitted. Mr. Kurz requested that I update the piece to inform my readers that Chairman Smith had not actually said: “the House Science Committee will do our best to avoid listening to scientists.” I notified the editor of the magazine who immediately printed a disclaimer at both the top and bottom of the page.

Republican Representative Lamar Smith of Texas

The reason the communications director is interested in public relations is that one could easily mistake the satire for the real thing. In fact Representative Smith does not listen to scientists because Representative Lamar Smith’s religion is a Christian Scientist !!!!!!!!! For those who don’t know what this means please read on.

Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices belonging to the metaphysical family of new religious movements.[3] It was developed in 19th-century New England by Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), who argued in her book Science and Health (1875) that sickness is an illusion that can be corrected by prayer alone. The book became Christian Science’s central text, along with the Bible, and by 2001 had sold ten million copies in 16 languages.[4] …

There are several key differences between Christian Science and orthodox Christian theology.[9] In particular adherents subscribe to a radical form of philosophical idealism, believing that reality is purely spiritual and the material world an illusion.[10] This includes the view that disease is a mental error rather than physical disorder, and that the sick should be treated, not by medicine, but by a form of prayer that seeks to correct the beliefs responsible for the illusion of ill health.[11] …

Between the 1880s and 1990s the avoidance of medical treatment was blamed for the deaths of several adherents and their children; parents and others were prosecuted for manslaughter or neglect and in a few cases convicted.[13]

Hopefully this gives you a sense of the philosophical beliefs that inform Representative Smith. If you would like you can read about Mary Baker Eddy’s beliefs in animal magnetism, witchcraft, and others superstitions. But the more you read the more you will be convinced that this man should not serve on this committee.

The Implications

Now Rep. Smith has a legal right to hold to whatever ignorant superstitions he likes. He is free to pray when ill rather than see his physician, which is exactly what he should do if he is faithful to his religious principles. It also makes sense that he opposes the expansion of medicaid under the ACA. For he doesn’t believe in medicine—he really doesn’t!

Remember this man chairs the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. If all of us, conservatives, liberals, libertarians, socialists, progressives, and everyone else don’t take steps to change this situation we will live in a theocracy which will slowly return this country to the Dark Ages. And that world of superstition and ignorance before the enlightenment was a horrific place. In it people with the plague prayed furiously … and then died miserably.

FInally, if you are a conservative interested in projecting American power in the world remember that American power depends, not on the outstanding level of physical fitness of the American public, but upon smart bombs, drones, missiles, submarines, engineering, computer software, and an economic policy based on the best economic theory not on economic dogma. Knowledge is power; ignorance leads to suffering.

Here by the way is the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology in action. (The most relevant segment begins at about 3 minutes into the video.) Watch the scientifically illiterate Republican members of Congress juvenile attempts to critique climate science. Let us hope the Dark Ages are not reborn.

October 4, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 4 – Hinduism – Part 2

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes from the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature.)

Divergent Interpretations – Hindus disagree regarding whether ultimate reality is personal or non-personal, (and whether the world is real or not.) Two seminal thinkers who espouse different views are Shankara (sometimes called the” Thomas Aquinas” of Hinduism) and Ramanuja.

Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta – This is a highly philosophical form of Hinduism. (The kind you would probably find in Vedanta centers in the US, especially those run by the Ramakrishna order of monks, a highly intellectual branch of Hinduism somewhat like the Jesuits are to Catholicism.) Shankara was interested in big philosophical questions like: “what is the relationship between Brahman and the world as it appears to our senses?” and “what is the relationship between Brahman and atman?” His is a philosophy of total unity. “For Shankara, Brahman is the only truth, the world is ultimately unreal, and the distinction between God and the individual is only an illusion.” Brahman is the only reality, and it is without attributes [it is not omnipotent, omniscient, personal, fatherly, etc.] To fully realize Brahman all distinctions between subjects and objects fade away [since there is only one reality]. Shankara concludes that the phenomenal world is false—it is maya, it is illusory.

Maya is the process through which we perceive multiplicity, even though reality is one. The world as it appears to our senses is not Brahman, and thus not ultimately real. This does not mean the world is imaginary; it is real; it exists. But it is not ultimate or absolute reality. [It is derivative from Brahman. This parallels Plato’s notion that things in this world are derivative from forms, which are more real.] The world of the senses exists in relation to Brahman the way a dream stands in relation to being awake. We may think that a rope in dim light is a snake, even though in good light we could tell the difference. [The parallels with Plato’s allegory of the cave in Shankara’s philosophy are striking.] By analogy, the world of multiplicity is superimposed on Brahman in the way the snake might have been superimposed on the rope. [Modern science has confirmed that humans are pattern-seekers who superimposed order when there is none. They see the face of a man on mars, Jesus in grilled cheese sandwiches, or destiny in sporting events that were really decided randomly by statistical fluctuation.] The experience of the world is finally revealed as false when one comes to the knowledge of Brahman.

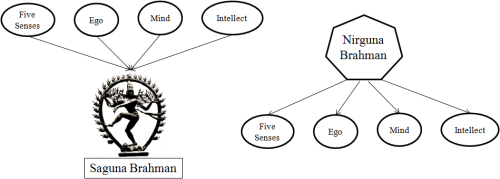

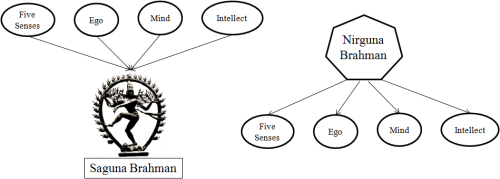

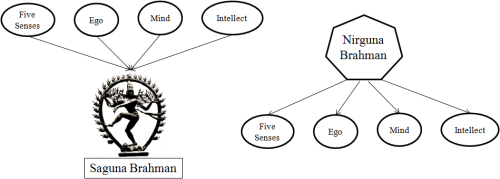

The idea of a personal god [Saguna Brahman] with attributes is ultimately an illusion, since Brahman is not limited by attributes. Such a being plays a role for those “still enmeshed in the cosmic illusion of maya.” In other words the notion of a personal god [who you can talk to and listen to] helps most people begin to leave behind the attachments of this world. But ultimately [Nirguna] Brahman is transpersonal, and without attributes. [Some philosopher said he preferred the personal god because the impersonal god seemed like a bowl of tapioca pudding.]

And Shankara also rejects the individual soul. Positing an individual soul is better than being attached to one’s ego and body, but the final realization is that the true self is Atman, or pure consciousness. Thus the world, god, and the individual soul are merely apparent reality—the ultimate and only reality is Brahman. Atman is Brahman. This realization is the ultimate one in Hinduism; it is the goal of spirituality. There is no ultimate distinction between subjects and objects [for there are no multiplicities that can be distinguished.] We are like drops of water trying to understand that we are ultimately united in one big ocean of being. This describes the quest for ultimate knowledge.

A necessary step in this spiritual journey is the realization that desire [especially for the things and activities of this world] must be eradicated. The highest spiritual path consists then of renunciation of the world followed by a lifetime of meditation designed to confirm the insight that “I am Brahman.” [If this sounds strange consider the typical vows of “poverty, chastity, and obedience” of priests and nuns and monks. All designed to turn one’s back on this world and focus—in different ways—on a more real spiritual world.]

Ramanuja’s Vishishta Adviata Vedanta – For Ramanuja the divine is personal, and different things are real, although they are still attributes of Brahman. Brahman is the sole reality but with different aspects or qualities. Ramanuja thus accepts a personal god—a god with personality and qualities—and rejects Brahman as “undifferentiated consciousness, contending that if this were true, any knowledge of Brahman would be impossible, since all knowledge depends on a differentiated “object.” [He is presupposing that knowledge is subjects knowing objects, and that knowledge of oneself—like being able to see your own eye without a mirror—is impossible.] The love of god entails a subject knowing and loving an object. Ramanuja wants to taste sugar not be sugar. [I suppose the theologians who wrote this centuries ago didn’t realize how bad sugar was!]

And the physical world is real for Ramanuja. It was created from divine love, and is the transformation of Brahman, similar to the way that milk transforms into cheese. In this view the world is not something to be overcome but something to be appreciated as the product of Brahman’s creativity. Maya refers not to illusion, but to this creative process. Thus the world is god’s body. [Here we find echoes of pantheists like Spinoza.] The world is an attribute of the eternal god analogously to how the body is an attribute of the soul. The soul is also part of god; it is both different and not different from god. [This “paradoxical logic” can be hard for Westerners. But the idea is that truth is often found in paradox.] The soul separates from Brahman at creation and returns to Brahman at dissolution. Yet the soul is still somehow both separate and eternal. [This probably sounds more familiar to those raised in Western monotheistic religions.]

The path to freedom for Ramanuja consists of action “that avoids both the attachment to the results of action and the abandonment of action.” [Do your homework and the results will take care of themselves.] We will be more effective if we are not overly concerned with the results of our actions. After all the world is lila, or god’s play, and we are actors not the playwright. There is so much beauty in the world that if we do our duty we will be fulfilled. We need not renounce the world, but revel in it. As for worshipping various manifestations of the gods, Ramanuja believes this helps most people as it appeals to their emotions. [Think of veneration of saints in Roman Catholicism.] The goal of these devotional acts is a feeling of the presence of gods, not oneness with a god. Finally the book notes that for the majority of Hindus “devotional practices in temples and home shrines dominate the Hindu tradition. [Something similar could be said about almost all religious traditions, they emphasize the emotional and devotional rather than the abstract and intellectual.]

Critical Discussion – Vedanta philosophy is highly textual—reliant on ancient scriptures—which most contemporary philosophers reject as a source of truth. It also makes transcendental claims, which is also problematic in modern western philosophy. Vedanta philosophy also has little to say about social and political philosophy or practical morality, concerned as it is with esoteric metaphysical concerns. Vedanta is also an elitist philosophy, generally excluding the uneducated.

Philosophy of Human Nature: Chapter 4 – Hinduism – Part 2

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

Divergent Interpretations – Hindus disagree regarding whether ultimate reality is personal or non-personal, (and whether the world is real or not.) Two seminal thinkers who espouse different views are Shankara (sometimes called the” Thomas Aquinas” of Hinduism) and Ramanuja.

Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta – This is a highly philosophical form of Hinduism. (The kind you would probably find in Vedanta centers in the US, especially those run by the Ramakrishna order of monks, a highly intellectual branch of Hinduism somewhat like the Jesuits are to Catholicism.) Shankara was interested in big philosophical questions like: “what is the relationship between Brahman and the world as it appears to our senses?” and “what is the relationship between Brahman and atman?” His is a philosophy of total unity. “For Shankara, Brahman is the only truth, the world is ultimately unreal, and the distinction between God and the individual is only an illusion.” Brahman is the only reality, and it is without attributes [it is not omnipotent, omniscient, personal, fatherly, etc.] To fully realize Brahman all distinctions between subjects and objects fade away [since there is only one reality]. Shankara concludes that the phenomenal world is false—it is maya, it is illusory.

Maya is the process through which we perceive multiplicity, even though reality is one. The world as it appears to our senses is not Brahman, and thus not ultimately real. This does not mean the world is imaginary; it is real; it exists. But it is not ultimate or absolute reality. [It is derivative from Brahman. This parallels Plato’s notion that things in this world are derivative from forms, which are more real.] The world of the senses exists in relation to Brahman the way a dream stands in relation to being awake. We may think that a rope in dim light is a snake, even though in good light we could tell the difference. [The parallels with Plato’s allegory of the cave in Shankara’s philosophy are striking.] By analogy, the world of multiplicity is superimposed on Brahman in the way the snake might have been superimposed on the rope. [Modern science has confirmed that humans are pattern-seekers who superimposed order when there is none. They see the face of a man on mars, Jesus in grilled cheese sandwiches, or destiny in sporting events that were really decided randomly by statistical fluctuation.] The experience of the world is finally revealed as false when one comes to the knowledge of Brahman.

The idea of a personal god [Saguna Brahman] with attributes is ultimately an illusion, since Brahman is not limited by attributes. Such a being plays a role for those “still enmeshed in the cosmic illusion of maya.” In other words the notion of a personal god [who you can talk to and listen to] helps most people begin to leave behind the attachments of this world. But ultimately [Nirguna] Brahman is transpersonal, and without attributes. [Some philosopher said he preferred the personal god because the impersonal god seemed like a bowl of tapioca pudding.]

And Shankara also rejects the individual soul. Positing an individual soul is better than being attached to one’s ego and body, but the final realization is that the true self is Atman, or pure consciousness. Thus the world, god, and the individual soul are merely apparent reality—the ultimate and only reality is Brahman. Atman is Brahman. This realization is the ultimate one in Hinduism; it is the goal of spirituality. There is no ultimate distinction between subjects and objects [for there are no multiplicities that can be distinguished.] We are like drops of water trying to understand that we are ultimately united in one big ocean of being. This describes the quest for ultimate knowledge.

A necessary step in this spiritual journey is the realization that desire [especially for the things and activities of this world] must be eradicated. The highest spiritual path consists then of renunciation of the world followed by a lifetime of meditation designed to confirm the insight that “I am Brahman.” [If this sounds strange consider the typical vows of “poverty, chastity, and obedience” of priests and nuns and monks. All designed to turn one’s back on this world and focus—in different ways—on a more real spiritual world.]

Ramanuja’s Vishishta Adviata Vedanta – For Ramanuja the divine is personal, and different things are real, although they are still attributes of Brahman. Brahman is the sole reality but with different aspects or qualities. Ramanuja thus accepts a personal god—a god with personality and qualities—and rejects Brahman as “undifferentiated consciousness, contending that if this were true, any knowledge of Brahman would be impossible, since all knowledge depends on a differentiated “object.” [He is presupposing that knowledge is subjects knowing objects, and that knowledge of oneself—like being able to see your own eye without a mirror—is impossible.] The love of god entails a subject knowing and loving an object. Ramanuja wants to taste sugar not be sugar. [I suppose the theologians who wrote this centuries ago didn’t realize how bad sugar was!]

And the physical world is real for Ramanuja. It was created from divine love, and is the transformation of Brahman, similar to the way that milk transforms into cheese. In this view the world is not something to be overcome but something to be appreciated as the product of Brahman’s creativity. Maya refers not to illusion, but to this creative process. Thus the world is god’s body. [Here we find echoes of pantheists like Spinoza.] The world is an attribute of the eternal god analogously to how the body is an attribute of the soul. The soul is also part of god; it is both different and not different from god. [This “paradoxical logic” can be hard for Westerners. But the idea is that truth is often found in paradox.] The soul separates from Brahman at creation and returns to Brahman at dissolution. Yet the soul is still somehow both separate and eternal. [This probably sounds more familiar to those raised in Western monotheistic religions.]

The path to freedom for Ramanuja consists of action “that avoids both the attachment to the results of action and the abandonment of action.” [Do your homework and the results will take care of themselves.] We will be more effective if we are not overly concerned with the results of our actions. After all the world is lila, or god’s play, and we are actors not the playwright. There is so much beauty in the world that if we do our duty we will be fulfilled. We need not renounce the world, but revel in it. As for worshipping various manifestations of the gods, Ramanuja believes this helps most people as it appeals to their emotions. [Think of veneration of saints in Roman Catholicism.] The goal of these devotional acts is a feeling of the presence of gods, not oneness with a god. Finally the book notes that for the majority of Hindus “devotional practices in temples and home shrines dominate the Hindu tradition. [Something similar could be said about almost all religious traditions, they emphasize the emotional and devotional rather than the abstract and intellectual.]

Critical Discussion – Vedanta philosophy is highly textual—reliant on ancient scriptures—which most contemporary philosophers reject as a source of truth. It also makes transcendental claims, which is also problematic in modern western philosophy. Vedanta philosophy also has little to say about social and political philosophy or practical morality, concerned as it is with esoteric metaphysical concerns. Vedanta is also an elitist philosophy, generally excluding the uneducated.

Philosophy of Human Nature: Part 4 – Hinduism

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

Divergent Interpretations – Hindus disagree regarding whether ultimate reality is personal or non-personal, (and whether the world is real or not.) Two seminal thinkers who espouse different views are Shankara (sometimes called the” Thomas Aquinas” of Hinduism) and Ramanuja.

Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta – This is a highly philosophical form of Hinduism. (The kind you would probably find in Vedanta centers in the US, especially those run by the Ramakrishna order of monks, a highly intellectual branch of Hinduism somewhat like the Jesuits are to Catholicism.) Shankara was interested in big philosophical questions like: “what is the relationship between Brahman and the world as it appears to our senses?” and “what is the relationship between Brahman and atman?” His is a philosophy of total unity. “For Shankara, Brahman is the only truth, the world is ultimately unreal, and the distinction between God and the individual is only an illusion.” Brahman is the only reality, and it is without attributes [it is not omnipotent, omniscient, personal, fatherly, etc.] To fully realize Brahman all distinctions between subjects and objects fade away [since there is only one reality]. Shankara concludes that the phenomenal world is false—it is maya, it is illusory.

Maya is the process through which we perceive multiplicity, even though reality is one. The world as it appears to our senses is not Brahman, and thus not ultimately real. This does not mean the world is imaginary; it is real; it exists. But it is not ultimate or absolute reality. [It is derivative from Brahman. This parallels Plato’s notion that things in this world are derivative from forms, which are more real.] The world of the senses exists in relation to Brahman the way a dream stands in relation to being awake. We may think that a rope in dim light is a snake, even though in good light we could tell the difference. [The parallels with Plato’s allegory of the cave in Shankara’s philosophy are striking.] By analogy, the world of multiplicity is superimposed on Brahman in the way the snake might have been superimposed on the rope. [Modern science has confirmed that humans are pattern-seekers who superimposed order when there is none. They see the face of a man on mars, Jesus in grilled cheese sandwiches, or destiny in sporting events that were really decided randomly by statistical fluctuation.] The experience of the world is finally revealed as false when one comes to the knowledge of Brahman.

The idea of a personal god [Saguna Brahman] with attributes is ultimately an illusion, since Brahman is not limited by attributes. Such a being plays a role for those “still enmeshed in the cosmic illusion of maya.” In other words the notion of a personal god [who you can talk to and listen to] helps most people begin to leave behind the attachments of this world. But ultimately [Nirguna] Brahman is transpersonal, and without attributes. [Some philosopher said he preferred the personal god because the impersonal god seemed like a bowl of tapioca pudding.]

And Shankara also rejects the individual soul. Positing an individual soul is better than being attached to one’s ego and body, but the final realization is that the true self is Atman, or pure consciousness. Thus the world, god, and the individual soul are merely apparent reality—the ultimate and only reality is Brahman. Atman is Brahman. This realization is the ultimate one in Hinduism; it is the goal of spirituality. There is no ultimate distinction between subjects and objects [for there are no multiplicities that can be distinguished.] We are like drops of water trying to understand that we are ultimately united in one big ocean of being. This describes the quest for ultimate knowledge.

A necessary step in this spiritual journey is the realization that desire [especially for the things and activities of this world] must be eradicated. The highest spiritual path consists then of renunciation of the world followed by a lifetime of meditation designed to confirm the insight that “I am Brahman.” [If this sounds strange consider the typical vows of “poverty, chastity, and obedience” of priests and nuns and monks. All designed to turn one’s back on this world and focus—in different ways—on a more real spiritual world.]

Ramanuja’s Vishishta Adviata Vedanta – For Ramanuja the divine is personal, and different things are real, although they are still attributes of Brahman. Brahman is the sole reality but with different aspects or qualities. Ramanuja thus accepts a personal god—a god with personality and qualities—and rejects Brahman as “undifferentiated consciousness, contending that if this were true, any knowledge of Brahman would be impossible, since all knowledge depends on a differentiated “object.” [He is presupposing that knowledge is subjects knowing objects, and that knowledge of oneself—like being able to see your own eye without a mirror—is impossible.] The love of god entails a subject knowing and loving an object. Ramanuja wants to taste sugar not be sugar. [I suppose the theologians who wrote this centuries ago didn’t realize how bad sugar was!]

And the physical world is real for Ramanuja. It was created from divine love, and is the transformation of Brahman, similar to the way that milk transforms into cheese. In this view the world is not something to be overcome but something to be appreciated as the product of Brahman’s creativity. Maya refers not to illusion, but to this creative process. Thus the world is god’s body. [Here we find echoes of pantheists like Spinoza.] The world is an attribute of the eternal god analogously to how the body is an attribute of the soul. The soul is also part of god; it is both different and not different from god. [This “paradoxical logic” can be hard for Westerners. But the idea is that truth is often found in paradox.] The soul separates from Brahman at creation and returns to Brahman at dissolution. Yet the soul is still somehow both separate and eternal. [This probably sounds more familiar to those raised in Western monotheistic religions.]

The path to freedom for Ramanuja consists of action “that avoids both the attachment to the results of action and the abandonment of action.” [Do your homework and the results will take care of themselves.] We will be more effective if we are not overly concerned with the results of our actions. After all the world is lila, or god’s play, and we are actors not the playwright. There is so much beauty in the world that if we do our duty we will be fulfilled. We need not renounce the world, but revel in it. As for worshipping various manifestations of the gods, Ramanuja believes this helps most people as it appeals to their emotions. [Think of veneration of saints in Roman Catholicism.] The goal of these devotional acts is a feeling of the presence of gods, not oneness with a god. Finally the book notes that for the majority of Hindus “devotional practices in temples and home shrines dominate the Hindu tradition. [Something similar could be said about almost all religious traditions, they emphasize the emotional and devotional rather than the abstract and intellectual.]

Critical Discussion – Vedanta philosophy is highly textual—reliant on ancient scriptures—which most contemporary philosophers reject as a source of truth. It also makes transcendental claims, which is also problematic in modern western philosophy. Vedanta philosophy also has little to say about social and political philosophy or practical morality, concerned as it is with esoteric metaphysical concerns. Vedanta is also an elitist philosophy, generally excluding the uneducated.

October 3, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 3 – Hinduism – Part 1

Om (Aum)

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are the notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature.)

While Hinduism is incredibly diverse (consider also that there are about 41,000 denominations of Christianity worldwide1) and there is no way to adequately capture that diversity in a few pages. In response the authors will focus on the Upanishads, the most foundational texts of Hinduism. Unlike Confucianism, Hinduism is a metaphysical philosophy whose “overall theme is one of ontological unity.” [Roughly the idea that all being is one. In fact, in non-dualist Vedanta, only Brahman is real.]

Theory of the Universe – All reality is one, in other words (philosophical) Hinduism a type of monism. This ultimate ground of all being [a phrase later adopted by 20th century Christian theologians like Paul Tillich and John T. Robinson] is called Brahman. Brahman is a force, power, or energy that “sustains the world;”an ultimate reality that causes or grounds existence, an essence which pervades all reality. Ultimately all of reality is one; all is Brahman.

But why then is it (or does it appear) that reality is a plurality composed of many things? A possible answer lies in the Hindu creation myth. All originates in nothingness [as it does in contemporary quantum cosmologies] except for Brahman [this is similar to creation “ex nihilo” in Christianity.] Being lonely Brahman divided into female and male and from this the entire plurality of the elements of the universe came into being. [It is hard to reconcile this story with the non-personal nature of Brahman.] However, “the original unity is never lost; it simply takes on the appearance of multiple forms.” [So multiplicity is ultimately an illusion—there is really only Brahman.]

This also implies that Braham is both immanent and transcendent—it both within and outside all reality. [This view is called panetheism, “… a belief system which posits that the divine (be it a monotheistic God, polytheistic gods, or an eternal cosmic animating force) interpenetrates every part of nature and timelessly extends beyond it.”2] These are the two aspects of Brahman. It is both all the changing things of the world and the unchanging ground of all things. This is the one ultimate reality seen from different perspectives. [Think of a gestalt picture like the faces/vases or young woman/old woman. One picture, two perspectives from which to see it.] But in the end there is only Brahman. Finally there is a tension in Hinduism between those who believe Brahman is ineffable and impossible to conceptualize, and those who disagree, identifying Brahman with everything.

Theory of Human Nature – We are all one and thus radically interconnected with all being. The self or soul within all, the Atman, is connected (identical?) with all other selves. We are like spokes all connected to a central hub or, more radically, what we are is identical to all of reality. Thus Hinduism distinguishes the transitory self as ego or I or persona (ahamkara), with the eternal, immortal self, the Atman. This true self is identical with Brahman. [Thus Atman is Brahman or, as it appears in the Vedas Tat Tvam Asi (Sanskrit: तत् त्वम् असि or तत्त्वमसि), … translated variously as "That art thou," "That thou art," "Thou art that," "You are that," or "That you are," or, for western ears, “you are god.”]

Atman is not an object of consciousness but the subject of consciousness—it is consciousness itself and thus cannot be known like other objects. [This distinction is important in contemporary, western philosophy of mind.] Our true selves are identical with the consciousness which animates all consciousness. We are not transient egos inside bodies but identical ultimately with all reality. Again Atman is (ultimately) Brahman. [You are identical with whatever power, force or energy animates all reality; you are (non-personal) god.] Moreover this true self migrates from body to body. [To make reincarnation plausible, consider that people die and other people are born, in other words Atman/Brahman continues. Remember this is a very brief, general description of Hinduism and there is a lot of disagreement in Hinduism like there is in any religion. For example some believe in Saguna Brahman, a personal god with attributes as opposed to Nirguna Brahman, transpersonal without attributes. Some Hindus are completely non-dualistic, there is only one reality; others are dualistic, etc.]

Diagnosis – The main problem of human existence is ignorance regarding the nature of ultimate reality. Most do not recognize the reality of infinite Brahman, and thus identify with the transitory objects of consciousness which all fade away. Since Atman is Brahman this ignorance is also ignorance of our true selves. [As we proceed into metaphysics one wonders how we know if any of this is true. Through experience? Meditation? The power of the arguments? Or could this all be speculation designed to comfort us at the thought of life’s transitory nature? How do we decide?] We identify with the phenomenal world instead of with Brahman. We concern ourselves with our little egos and small threats of offenses to them, rather than recognizing that are egos are essentially illusory, and we are identical to all reality. We are alienated from ourselves, from others, and from all reality. We are isolated and lonely.

This (misguided) individualism is caused by karma. [This is simply a moral law of cause and effect.] This means that our actions are not free but determined by past desires and actions. We are in psychological bondage to previous actions and the desires that caused them. [Consider the binding nature of previous gambling, smoking, eating junk food, aggression, etc.] Hindu meditation in large part is an attempt to get in touch with our true nature and free us from egoistic desires.

Prescription – Hinduism is generally optimistic about attaining freedom from desire and discovery our true nature. This is done by multiple paths. The beginning of freedom though is a special kind of knowledge. [The basic ways (or yogas) are the paths of: 1) knowledge; 2) love; 3) work; and 4) psychological exercises. The way one chooses depends on their personality.]

Philosophy of Human Nature: Chapter 3 – Hinduism – Part 1

Om (Aum)

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

While Hinduism is incredibly diverse (consider also that there are about 41,000 denominations of Christianity worldwide1) and there is no way to adequately capture that diversity in a few pages. In response the authors will focus on the Upanishads, the most foundational texts of Hinduism. Unlike Confucianism, Hinduism is a metaphysical philosophy whose “overall theme is one of ontological unity.” [Roughly the idea that all being is one. In fact, in non-dualist Vedanta, only Brahman is real.]

Theory of the Universe – All reality is one, in other words (philosophical) Hinduism a type of monism. This ultimate ground of all being [a phrase later adopted by 20th century Christian theologians like Paul Tillich and John T. Robinson] is called Brahman. Brahman is a force, power, or energy that “sustains the world;”an ultimate reality that causes or grounds existence, an essence which pervades all reality. Ultimately all of reality is one; all is Brahman.

But why then is it (or does it appear) that reality is a plurality composed of many things? A possible answer lies in the Hindu creation myth. All originates in nothingness [as it does in contemporary quantum cosmologies] except for Brahman [this is similar to creation “ex nihilo” in Christianity.] Being lonely Brahman divided into female and male and from this the entire plurality of the elements of the universe came into being. [It is hard to reconcile this story with the non-personal nature of Brahman.] However, “the original unity is never lost; it simply takes on the appearance of multiple forms.” [So multiplicity is ultimately an illusion—there is really only Brahman.]

This also implies that Braham is both immanent and transcendent—it both within and outside all reality. [This view is called panetheism, “… a belief system which posits that the divine (be it a monotheistic God, polytheistic gods, or an eternal cosmic animating force) interpenetrates every part of nature and timelessly extends beyond it.”2] These are the two aspects of Brahman. It is both all the changing things of the world and the unchanging ground of all things. This is the one ultimate reality seen from different perspectives. [Think of a gestalt picture like the faces/vases or young woman/old woman. One picture, two perspectives from which to see it.] But in the end there is only Brahman. Finally there is a tension in Hinduism between those who believe Brahman is ineffable and impossible to conceptualize, and those who disagree, identifying Brahman with everything.

Theory of Human Nature – We are all one and thus radically interconnected with all being. The self or soul within all, the Atman, is connected (identical?) with all other selves. We are like spokes all connected to a central hub or, more radically, what we are is identical to all of reality. Thus Hinduism distinguishes the transitory self as ego or I or persona (ahamkara), with the eternal, immortal self, the Atman. This true self is identical with Brahman. [Thus Atman is Brahman or, as it appears in the Vedas Tat Tvam Asi (Sanskrit: तत् त्वम् असि or तत्त्वमसि), … translated variously as "That art thou," "That thou art," "Thou art that," "You are that," or "That you are," or, for western ears, “you are god.”]

Atman is not an object of consciousness but the subject of consciousness—it is consciousness itself and thus cannot be known like other objects. [This distinction is important in contemporary, western philosophy of mind.] Our true selves are identical with the consciousness which animates all consciousness. We are not transient egos inside bodies but identical ultimately with all reality. Again Atman is (ultimately) Brahman. [You are identical with whatever power, force or energy animates all reality; you are (non-personal) god.] Moreover this true self migrates from body to body. [To make reincarnation plausible, consider that people die and other people are born, in other words Atman/Brahman continues. Remember this is a very brief, general description of Hinduism and there is a lot of disagreement in Hinduism like there is in any religion. For example some believe in Saguna Brahman, a personal god with attributes as opposed to Nirguna Brahman, transpersonal without attributes. Some Hindus are completely non-dualistic, there is only one reality; others are dualistic, etc.]

Diagnosis – The main problem of human existence is ignorance regarding the nature of ultimate reality. Most do not recognize the reality of infinite Brahman, and thus identify with the transitory objects of consciousness which all fade away. Since Atman is Brahman this ignorance is also ignorance of our true selves. [As we proceed into metaphysics one wonders how we know if any of this is true. Through experience? Meditation? The power of the arguments? Or could this all be speculation designed to comfort us at the thought of life’s transitory nature? How do we decide?] We identify with the phenomenal world instead of with Brahman. We concern ourselves with our little egos and small threats of offenses to them, rather than recognizing that are egos are essentially illusory, and we are identical to all reality. We are alienated from ourselves, from others, and from all reality. We are isolated and lonely.

This (misguided) individualism is caused by karma. [This is simply a moral law of cause and effect.] This means that our actions are not free but determined by past desires and actions. We are in psychological bondage to previous actions and the desires that caused them. [Consider the binding nature of previous gambling, smoking, eating junk food, aggression, etc.] Hindu meditation in large part is an attempt to get in touch with our true nature and free us from egoistic desires.

Prescription – Hinduism is generally optimistic about attaining freedom from desire and discovery our true nature. This is done by multiple paths. The beginning of freedom though is a special kind of knowledge. [The basic ways (or yogas) are the paths of: 1) knowledge; 2) love; 3) work; and 4) psychological exercises. The way one chooses depends on their personality.]

Philosophy of Human Nature: Part 3 – Hinduism

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

While Hinduism is incredibly diverse (consider also that there are about 41,000 denominations of Christianity worldwide1) and there is no way to adequately capture that diversity in a few pages. In response the authors will focus on the Upanishads, the most foundational texts of Hinduism. Unlike Confucianism, Hinduism is a metaphysical philosophy whose “overall theme is one of ontological unity.” [Roughly the idea that all being is one. In fact, in non-dualist Vedanta, only Brahman is real.]

Theory of the Universe – All reality is one, in other words (philosophical) Hinduism a type of monism. This ultimate ground of all being [a phrase later adopted by 20th century Christian theologians like Paul Tillich and John T. Robinson] is called Brahman. Brahman is a force, power, or energy that “sustains the world;”an ultimate reality that causes or grounds existence, an essence which pervades all reality. Ultimately all of reality is one; all is Brahman.

But why then is it (or does it appear) that reality is a plurality composed of many things? A possible answer lies in the Hindu creation myth. All originates in nothingness [as it does in contemporary quantum cosmologies] except for Brahman [this is similar to creation “ex nihilo” in Christianity.] Being lonely Brahman divided into female and male and from this the entire plurality of the elements of the universe came into being. [It is hard to reconcile this story with the non-personal nature of Brahman.] However, “the original unity is never lost; it simply takes on the appearance of multiple forms.” [So multiplicity is ultimately an illusion—there is really only Brahman.]

This also implies that Braham is both immanent and transcendent—it both within and outside all reality. [This view is called panetheism, “… a belief system which posits that the divine (be it a monotheistic God, polytheistic gods, or an eternal cosmic animating force) interpenetrates every part of nature and timelessly extends beyond it.”2] These are the two aspects of Brahman. It is both all the changing things of the world and the unchanging ground of all things. This is the one ultimate reality seen from different perspectives. [Think of a gestalt picture like the faces/vases or young woman/old woman. One picture, two perspectives from which to see it.] But in the end there is only Brahman. Finally there is a tension in Hinduism between those who believe Brahman is ineffable and impossible to conceptualize, and those who disagree, identifying Brahman with everything.

Theory of Human Nature – We are all one and thus radically interconnected with all being. The self or soul within all, the Atman, is connected (identical?) with all other selves. We are like spokes all connected to a central hub or, more radically, what we are is identical to all of reality. Thus Hinduism distinguishes the transitory self as ego or I or persona (ahamkara), with the eternal, immortal self, the Atman. This true self is identical with Brahman. [Thus Atman is Brahman or, as it appears in the Vedas Tat Tvam Asi (Sanskrit: तत् त्वम् असि or तत्त्वमसि), … translated variously as "That art thou," "That thou art," "Thou art that," "You are that," or "That you are," or, for western ears, “you are god.”]

Atman is not an object of consciousness but the subject of consciousness—it is consciousness itself and thus cannot be known like other objects. [This distinction is important in contemporary, western philosophy of mind.] Our true selves are identical with the consciousness which animates all consciousness. We are not transient egos inside bodies but identical ultimately with all reality. Again Atman is (ultimately) Brahman. [You are identical with whatever power, force or energy animates all reality; you are (non-personal) god.] Moreover this true self migrates from body to body. [To make reincarnation plausible, consider that people die and other people are born, in other words Atman/Brahman continues. Remember this is a very brief, general description of Hinduism and there is a lot of disagreement in Hinduism like there is in any religion. For example some believe in Saguna Brahman, a personal god with attributes as opposed to Nirguna Brahman, transpersonal without attributes. Some Hindus are completely non-dualistic, there is only one reality; others are dualistic, etc.]

Diagnosis – The main problem of human existence is ignorance regarding the nature of ultimate reality. Most do not recognize the reality of infinite Brahman, and thus identify with the transitory objects of consciousness which all fade away. Since Atman is Brahman this ignorance is also ignorance of our true selves. [As we proceed into metaphysics one wonders how we know if any of this is true. Through experience? Meditation? The power of the arguments? Or could this all be speculation designed to comfort us at the thought of life’s transitory nature? How do we decide?] We identify with the phenomenal world instead of with Brahman. We concern ourselves with our little egos and small threats of offenses to them, rather than recognizing that are egos are essentially illusory, and we are identical to all reality. We are alienated from ourselves, from others, and from all reality. We are isolated and lonely.

This (misguided) individualism is caused by karma. [This is simply a moral law of cause and effect.] This means that our actions are not free but determined by past desires and actions. We are in psychological bondage to previous actions and the desires that caused them. [Consider the binding nature of previous gambling, smoking, eating junk food, aggression, etc.] Hindu meditation in large part is an attempt to get in touch with our true nature and free us from egoistic desires.

Prescription – Hinduism is generally optimistic about attaining freedom from desire and discovery our true nature. This is done by multiple paths. The beginning of freedom though is a special kind of knowledge. [The basic ways (or yogas) are the paths of: 1) knowledge; 2) love; 3) work; and 4) psychological exercises. The way one chooses depends on their personality.]

October 2, 2014

Absurd Arguments Against Atheism

I recently came across a poorly argued piece in The Huffington Post’s religion section entitled, “The Three Mistakes Atheists Make.” Yes, it is easy for a professional philosopher to find fault with a philosophical piece written by non-professional, but this article was so poorly reasoned and so rife with fallacies of informal logic that I felt obliged to critique it. Certainly those predisposed to accepting its premises will find it comforting, but any critical thinker, including those sympathetic with the Rabbi’s views, would find it woefully inadequate.

Rabbi Eric H. Yoffie basis his critique on a brief interview of Philip Kitcher about his forthcoming book, Life After Faith: The Case for Secular Humanism. The interview was conducted for the New York Times by Professor Gary Gutting, a Catholic philosopher at the University of Notre Dame. So while the book is not yet out, and Rabbi Yoffie has not yet read it, he dismisses it based on one brief interview. (I briefly summarized and commented on the interview in a previous post.)

Now Philip Kitcher is the John Dewey Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University who is one of the most notable and respected living philosophers. Thus it is unlikely that the Rabbi’s brief remarks refute the thorough, subtle, and sophisticated argument of a book which he has not read. Moreover, deeper thinkers than Rabbi Yoffie who have actually read the book have responded differently. To his credit Professor Gutting, who one suspects would not be sympathetic to an atheistic argument, says this: “This is the most philosophically sophisticated and rigorous defense of atheism in the contemporary literature. Life After Faith provides an informed and responsible statement of the secular humanist viewpoint.”

And praise of the books erudite sophistication has come from other intellectuals as well. The Jewish author Leon Wieseltier, child of Holocaust survivors and fluent Hebrew speaker, argues:

Philip Kitcher has composed the most formidable defense of the secular view of life since Dewey. Unlike almost all of contemporary atheism, Life After Faith is utterly devoid of cartoons and caricatures of religion. It is, instead, a sober and soulful book, an exemplary practice of philosophical reflection. Scrupulous in its argument, elegant in its style, humane in its spirit, it is animated by a stirring aspiration to wisdom. Even as I quarrel with it I admire it.

Professor David Hollinger, the Preston Hotchkis Professor of History emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, asserts: “This book is a deeper and more convincing critique of traditional religious belief than anything written by the New Atheists. Kitcher deals conscientiously with every objection to secular humanism and shows why each one fails.” The Cambridge educated Kwame Anthony Appiah, a most important contemporary philosophers who holds of a joint professorship in both law and philosophy at New York University, maintains: “Philip Kitcher takes seriously the challenge of showing how, without a belief in the transcendent, we can still live lives that are rich with meaning, because they are thoroughly committed to the pursuit of what is good and beautiful and true.”

Now it is true that these rave reviews from intellectuals across a wide range of ideological positions do not count definitely against the Rabbi’s brief arguments, but they do count strongly against his generally dismissive tone. When the Rabbi says, “I hear in his words a tone that is closer to defensive desperation than confident conviction,” we have to wonder if the Rabbi is hearing through prejudiced ears. The three common and evidently self-evident mistakes that atheists make according to rabbi are: 1)They dismiss, often with contempt, the religious experience of other people; 2) They assert that since there are no valid religions but that religions do good things, the task of smart people is to create a religion without God — or, in other words, a religion without religion; 3) They see the world of belief in black and white, either/or terms. Let me briefly respond to each to each of these (ridiculous) claims.

Regarding claim #1 – (They dismiss, often with contempt, the religious experience of other people.)

Rabbi Yoffie begins by suggesting that religious experience is immune to the classic arguments against the existence of gods. While it is true that such critiques do not refute religious experience, he omits that there are strong arguments against these experiences as well. As Kitcher points out in the interview biological, psychological, and social reasons can be provided to convincingly explain these experiences.

Yet the Rabbi interprets this to mean that Kitcher is “asserting with certainty that no one else is capable of a God encounter rooted in transcendence and holiness.” I assure you that Kitcher is making no such claim. As good a philosopher as Kitcher knows there is nothing logically impossible about the source of religious experience being something supernatural. What he is saying is that an inference to the best explanation makes it much, much more likely that the origin is some psychological phenomena. As for it being unlikely that the source is a divine entity, the Rabbi says “… on what possible basis can he make such a claim?” Of course the answer is obvious. He makes that claim based on the increasing ability of science to explain so-called religious and mystical experiences.

Furthermore, even if such experiences aid the Rabbi in his belief, they provide only soft or subjective justifications for belief. They can never by their very nature provide hard or objective justification. That is the justify belief for the experiencer, but never for the one who doesn’t have the experience. I am in no way justified in believing anything based on your subjective, psychological experiences, especially when they claim something extraordinary such as” “I was talking with Zeus last night.”

Regarding claim #2 – (They assert that since there are no valid religions but that religions do good things, the task of smart people is to create a religion without God — or, in other words, a religion without religion.)

Philosophers don’t simply assert that there are no valid religions. Less than 15% of contemporary philosophers are theists primarily because the traditional arguments for the existence of gods have been under attack since the Enlightenment and because science has provided convincing alternative explanations for religious phenomena.

As for the claims of Kitcher, Dworkin, de Botton and others that we should promote values without fundamentalism and supernaturalism, Yoffie responds that such proposals don’t work. He argues:

Philosophy can do many things, but it cannot create deep loyalty, profound engagement, or a willingness to sacrifice for one’s beliefs. Religion, whether of the liberal or orthodox variety, does precisely that. And it does so by retaining those things that Kitcher proposes to jettison: a community of believers connected to the holy and convictions rooted in both ritual and faith.

This would come as quite a surprise to the citizens of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, The Netherlands, France, Germany and others countries where religious belief has virtually disappeared but which are generally regarded as the best countries on earth in which to live. Countries with strong social safety nets, little economic inequality, low rates of incarceration, infant morality and crime, along with high levels of educational attainment, generous family leave policies, mandated vacation time, and universal health care. That we need religious belief to have good societies is absurd claim, one repudiated by the evidence.

Regarding claim #3 (They see the world of belief in black and white, either/or terms.)

While Kitcher rightly notes that the incredible diversity of religious doctrines makes it unlikely that any one religion is true, (there are about 41,000 denominations of Christianity in the world alone), Yoffie responds: “If there are 10,000 contrary religious doctrines, it does not follow that they all are false.” Well it doesn’t follow that they are all false, unless you are a religious exclusivist. In that case only one would be true and the others false. (And I’d bet you think the true one is the one you believe in!) But if you are a religious universalist, if you think that all religions are different paths to the same mountaintop, then they can all be (somewhat) true. But what Kitcher is pointing out is that these vast discrepancies about religious beliefs strongly suggest that any particular religious claim is unlikely to be true. This strongly suggest that beliefs about religion are not like beliefs about physics and biology, about which there is consensus among the educated.

Now at this point Yoffie employs the classic fallacy of the straw man—arguing against an easily attacked position that your opponent doesn’t hold. He concludes:

Kitcher, like others in the atheist camp, sees the world in terms of dichotomies: You are a theist or a non-theist, a religious person or a non-religious person. But, of course, this is not the way that most people function. Some religious people are fanatical, but most are not. The world of belief, which includes a majority of the human race, consists of people who believe but are not always sure; who accept God some of the time but not all the time; and who know that theology is a matter of questions and uncertainties, painted in hues of gray.

It is patently absurd to suggest that Kitcher doesn’t realize that a multiplicity of religious views exists. Surely Kitcher wouldn’t be surprised, nor would he recall his book, because the good Rabbi has informed him that there are agnostics, process theologians, death-of-god theologians, fundamentalist and more. But it is Rabbi Yoffie’s conclusion that finally gives away his position:

Professor Kitcher offers a challenging thesis, but in the final analysis, he—and others like him—simply do not understand a central fact of human history: Drawing on their deepest experiences, most people instinctively reach out to God, and God in turn reaches out to them.

There you have it. For the Rabbi it is simply a fact that people reach out to Yahweh, God, Zeus, Apollo, and Thor and the gods in turn respond. His argument, as it turns out, is circular. Arguments against the existence of the gods don’t work because the gods exist.

September 30, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 2 – Confucianism – Part 2

Students Taking Imperial Exams

Students Taking Imperial Exams

Confucianism: The Way of the Sages

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes from the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature.)

Prescription – Confucius prescribes self-discipline for individuals and rulers in order to cure the ills of society. [I wrote about this briefly in a recent blog entry “The World Desperately Needs Better People”: http://reasonandmeaning.com/2014/08/21/growing-as-people/ ] In other words society will be better when the people who make it up are better. This approach provides answers to the 5 problems listed above.

Do what is right because it is right, not for profit. [Can one do this in our current economic system? And if not, do we live in an economic system that prevents us from being moral? And if this is true, what an indictment of the system this would be.] By struggling to be moral we align ourselves with the decree of heaven, with something like the natural order. We also shield ourselves against disappointment because we care about moral virtue rather than those things we cannot be assured of getting—like fame and fortune. Moral excellence is its own reward, whether we are recognized for it or not. This encourages us to keep working for righteousness in the world even if no one else appreciates it. If we are motivated by what is right, we will find joy in our efforts even if we do not fully succeed. Thus we also accept that destiny plays a role in human life. But moral excellence is within our control and we should struggle to attain it through self-discipline. We should cultivate self, not social recognition, fame or fortune.

Cultivating self [being the change you want to see in the world as Gandhi put it] implies you will be a better family member. [Are you struck by the emphasis on the community rather than the individual as is the case in much of Western culture?] Being a good family member reverberates through society. A person who is good to their parents and siblings and children will be good to others as well. Transformation of the self and benevolence begin in the family and spread outward. [Confucius suggests that we should follow the ways of our parents, if they were virtuous. This may sound strange to our individualistic ears, but the idea is that we learn from the experience and virtue of those who have gone before us. Think of something like Dan Fogelberg’s song: “The Leader of the Band.”]

Regarding lying, Confucius says we need word and deed to conform, in other words, actions should reflect words. [So don’t say, “I care about you and I will be a good public servant if you really just want money and power.] If we all lie, trust will evaporate. [Think how communication would fall apart if you couldn’t ordinarily assume people were telling the truth. Why ask for the time or directions if people usually lie?] “Words are easy to produce; if a person or government uses them to conceal the truth, then social chaos ensues. Trust is a critical ingredient of all dependable social interaction.”

The answer to ignorance of the past is education, study and scholarship. Most important for Confucius is the study of the cultural legacy of our past, for the purpose of revealing how moral perfection might be achieved. [Today, for us in the West, this would mean something like the “Great Books” curriculum. ] Such education is also crucial for good government. Only after a good education should one be allowed to be a leader. [Confucius and China took this very seriously and the result was the Imperial exams as a prerequisite to hold political office. How our own society would benefit if its leaders had to pass some kind of examinations!]

Benevolence (kindness, goodwill, charity, compassion, generosity, munificence) is the primary means of moral perfection. For Confucius, the process of becoming benevolent involves 3 elements: a) clinging to benevolence at all times; b) treating others as you would like to be treated and not doing to others what you don’t want done to you; and c) habituating actionaccording to moral rules, which we learn from studying the classics. Benevolence is achieved by acting in accord with the moral rules we learn by studying which is to live according to the way of the heavens.

This goal of attaining self-discipline, self-mastery, or self-perfection takes a lifetime. Benevolence is the outward expression of this internal state, and serves as a model to others who want to be sages. For the sages benevolent action naturally flows from them; it is the expression of an internal perfected state. For the self-disciplined person, their behavior is modeled on the sages, with the goal of becoming sages. [Hence the idea that moral perfection is a process of development.] As Confucius says the master and student may appear similar from the outside, but the master does things naturally and spontaneously in a way that the student does not. In the end moral perfection may be achieved by studying the classics and becoming a sage. If people bettered themselves, society would improve. [However I think Confucius would agree with Spinoza]:

“If the way which I have pointed out as leading to this result seems exceedingly hard, it may nevertheless be discovered. Needs must it be hard, since it is so seldom found. How would it be possible, if salvation were ready to our hand, and could without great labour be found, that it should be by almost all men neglected? But all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare.”

Later Developments – But is human nature originally good or evil? Mencius subscribed to the former, while Hsun-tzu to the latter. Mencius tries to refute the view that human nature is neither good nor bad, arguing that humans are inherently good. For Mencius the heart is a gift from the heavens which inherently contains compassion, shame, courtesy, and a sense of morality which will sprout into benevolence, dutifulness, observation of rites, and wisdom. Nonetheless Mencius grants that people are also selfish and the good qualities of the human heart must be cultivated. Thus the right conditions must apply. [[I assume this process of development will come to fruition under conditions like parental love, good education, good society, physical safety, health care, food, clothing, shelter, etc.] Mencius even offers an argument that humans are inherently good: if they saw a child in danger they would instinctively try to help the child. [Of course this argument only works if what Mencius is saying is true.]

Hsun-tzu argued that our interior life is dominated by desires. As these desires are unlimited and resources limited, a natural conflict between people will result. [Eerily reminiscent of Hobbes’ argument that the state of nature is a state of war precisely because the things we want—fame, fortune, etc.—are in short supply.] Our nature thus is generally bad and we must work consciously to be good. [Reminds one of Hepburn’s remark to Bogart in the movie, “The African Queen.” She tells him that our nature is something we should overcome.] Hsun-tzu says that the desire for profit, as well as envy, hatred, and desire are our natural tendencies which lead to strife, violence, crime, and wantonness. Still Hsu-tzu believed that with proper education, training and ritual everyone could become morally excellent. This takes effort and is aided by a good culture.

Despite their disagreements both Mencius and Hsun-tzu agree that the path of sagehood consists of action based on the examples of previous sages. For Hsun-tzu we are naturally warped boards that need to be straightened; for Mencius we are relatively straight boards that can be warped.

Critical discussion –

Confucianism teaches obedience to superiors, which is good if the heads of family or state are good. If they are not the whole system is undermined. Confucius thus emphasized the moral character of leaders. [As did Plato.]

Looking to the past may restrict creativity and originality in the present. Should we be so enamored with past wisdom and the scholars that interpret it? Is morality objective and are those who interpret it impartial?

The common people and wisdom seem to be excluded from the Confucian system.

The pragmatic, utilitarian, anti-metaphysical nature of Confucianism, which emphasizes social affairs, can be a small, limited world for those who have metaphysical concerns.

Despite these criticisms, neo-Confucianism may be able to be modified “as a positive resource for thinking about ways to overcome the destructive side of modernization that threatens both human communities and the natural world.”