Philosophy of Human Nature: Chapter 4 – Hinduism – Part 2

Upanishadic Hinduism: Quest for Ultimate Knowledge

Divergent Interpretations – Hindus disagree regarding whether ultimate reality is personal or non-personal, (and whether the world is real or not.) Two seminal thinkers who espouse different views are Shankara (sometimes called the” Thomas Aquinas” of Hinduism) and Ramanuja.

Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta – This is a highly philosophical form of Hinduism. (The kind you would probably find in Vedanta centers in the US, especially those run by the Ramakrishna order of monks, a highly intellectual branch of Hinduism somewhat like the Jesuits are to Catholicism.) Shankara was interested in big philosophical questions like: “what is the relationship between Brahman and the world as it appears to our senses?” and “what is the relationship between Brahman and atman?” His is a philosophy of total unity. “For Shankara, Brahman is the only truth, the world is ultimately unreal, and the distinction between God and the individual is only an illusion.” Brahman is the only reality, and it is without attributes [it is not omnipotent, omniscient, personal, fatherly, etc.] To fully realize Brahman all distinctions between subjects and objects fade away [since there is only one reality]. Shankara concludes that the phenomenal world is false—it is maya, it is illusory.

Maya is the process through which we perceive multiplicity, even though reality is one. The world as it appears to our senses is not Brahman, and thus not ultimately real. This does not mean the world is imaginary; it is real; it exists. But it is not ultimate or absolute reality. [It is derivative from Brahman. This parallels Plato’s notion that things in this world are derivative from forms, which are more real.] The world of the senses exists in relation to Brahman the way a dream stands in relation to being awake. We may think that a rope in dim light is a snake, even though in good light we could tell the difference. [The parallels with Plato’s allegory of the cave in Shankara’s philosophy are striking.] By analogy, the world of multiplicity is superimposed on Brahman in the way the snake might have been superimposed on the rope. [Modern science has confirmed that humans are pattern-seekers who superimposed order when there is none. They see the face of a man on mars, Jesus in grilled cheese sandwiches, or destiny in sporting events that were really decided randomly by statistical fluctuation.] The experience of the world is finally revealed as false when one comes to the knowledge of Brahman.

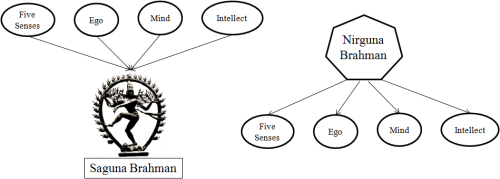

The idea of a personal god [Saguna Brahman] with attributes is ultimately an illusion, since Brahman is not limited by attributes. Such a being plays a role for those “still enmeshed in the cosmic illusion of maya.” In other words the notion of a personal god [who you can talk to and listen to] helps most people begin to leave behind the attachments of this world. But ultimately [Nirguna] Brahman is transpersonal, and without attributes. [Some philosopher said he preferred the personal god because the impersonal god seemed like a bowl of tapioca pudding.]

And Shankara also rejects the individual soul. Positing an individual soul is better than being attached to one’s ego and body, but the final realization is that the true self is Atman, or pure consciousness. Thus the world, god, and the individual soul are merely apparent reality—the ultimate and only reality is Brahman. Atman is Brahman. This realization is the ultimate one in Hinduism; it is the goal of spirituality. There is no ultimate distinction between subjects and objects [for there are no multiplicities that can be distinguished.] We are like drops of water trying to understand that we are ultimately united in one big ocean of being. This describes the quest for ultimate knowledge.

A necessary step in this spiritual journey is the realization that desire [especially for the things and activities of this world] must be eradicated. The highest spiritual path consists then of renunciation of the world followed by a lifetime of meditation designed to confirm the insight that “I am Brahman.” [If this sounds strange consider the typical vows of “poverty, chastity, and obedience” of priests and nuns and monks. All designed to turn one’s back on this world and focus—in different ways—on a more real spiritual world.]

Ramanuja’s Vishishta Adviata Vedanta – For Ramanuja the divine is personal, and different things are real, although they are still attributes of Brahman. Brahman is the sole reality but with different aspects or qualities. Ramanuja thus accepts a personal god—a god with personality and qualities—and rejects Brahman as “undifferentiated consciousness, contending that if this were true, any knowledge of Brahman would be impossible, since all knowledge depends on a differentiated “object.” [He is presupposing that knowledge is subjects knowing objects, and that knowledge of oneself—like being able to see your own eye without a mirror—is impossible.] The love of god entails a subject knowing and loving an object. Ramanuja wants to taste sugar not be sugar. [I suppose the theologians who wrote this centuries ago didn’t realize how bad sugar was!]

And the physical world is real for Ramanuja. It was created from divine love, and is the transformation of Brahman, similar to the way that milk transforms into cheese. In this view the world is not something to be overcome but something to be appreciated as the product of Brahman’s creativity. Maya refers not to illusion, but to this creative process. Thus the world is god’s body. [Here we find echoes of pantheists like Spinoza.] The world is an attribute of the eternal god analogously to how the body is an attribute of the soul. The soul is also part of god; it is both different and not different from god. [This “paradoxical logic” can be hard for Westerners. But the idea is that truth is often found in paradox.] The soul separates from Brahman at creation and returns to Brahman at dissolution. Yet the soul is still somehow both separate and eternal. [This probably sounds more familiar to those raised in Western monotheistic religions.]

The path to freedom for Ramanuja consists of action “that avoids both the attachment to the results of action and the abandonment of action.” [Do your homework and the results will take care of themselves.] We will be more effective if we are not overly concerned with the results of our actions. After all the world is lila, or god’s play, and we are actors not the playwright. There is so much beauty in the world that if we do our duty we will be fulfilled. We need not renounce the world, but revel in it. As for worshipping various manifestations of the gods, Ramanuja believes this helps most people as it appeals to their emotions. [Think of veneration of saints in Roman Catholicism.] The goal of these devotional acts is a feeling of the presence of gods, not oneness with a god. Finally the book notes that for the majority of Hindus “devotional practices in temples and home shrines dominate the Hindu tradition. [Something similar could be said about almost all religious traditions, they emphasize the emotional and devotional rather than the abstract and intellectual.]

Critical Discussion – Vedanta philosophy is highly textual—reliant on ancient scriptures—which most contemporary philosophers reject as a source of truth. It also makes transcendental claims, which is also problematic in modern western philosophy. Vedanta philosophy also has little to say about social and political philosophy or practical morality, concerned as it is with esoteric metaphysical concerns. Vedanta is also an elitist philosophy, generally excluding the uneducated.