John G. Messerly's Blog, page 137

September 25, 2014

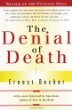

The Denial of Death

Last month the American comedian and actor Robin Williams died. A massive outpouring of public grief followed but now, a little more than a month later, it has all but vanished. What then, I wondered, was all that grief about? And for someone we didn’t even really know.

While thinking about this I came across an insightful article on by Peter Finocchiaro. He first considers the idea that much of this grief was not earnest—that it was more about the person expressing the grief. All the twitter and Facebook activity was mostly about one’s favorite films and how much one was grieving. Finocchiaro thinks egotism is part of the explanation for the public outpouring. After all how many of our lives were really changed by a Robin Williams movie? Still Finocchiaro thinks there is more to it. “Why, exactly, are we making it about us?”

He next considers that our concern for celebrities is a manifestation of the psychological phenomenon called “Basking in Reflective Glory.” By associating with celebrities we feel special, and when they die some of that specialness disappears. Thus we cling to them as best we can by telling everyone how much we loved them or their work. Again Finocchiaro thinks this is a part, but not all of the answer.

At the deepest level Finocchiaro believes this grief is about something deeper—it is about our own fear of death. And I think he is right. In this context Finocchiaro reminds us of the main thesis of the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker‘s 1973 bestseller and Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction, “The Denial of Death.” There Becker argues:

that the refusal to accept our mortality—a fundamental but nearly invisible pathology, baked right into the human condition—is the literal cause of all evil in the world … This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression—and with all this yet to die.

In response, Becker contends, we make heroes of famous people and cling fanatically to the ideas of religion, nationalism, sports teams, alma maters, and other group loyalties. Becker also argues that while deifying our heroes and social structures may ameliorate our existential dread, it also leads to prejudice, inequality, and war—our attraction to celebrities and ideologies is a double-edge sword. But all of this emanates from our desire to transcend death, and this is why we feel grief when kings or presidents or celebrities die—it reminds us of the existential dread we all feel but don’t want to talk about.

Finocchiaro concludes by talking about his own death in an honest and moving way.

Something I don’t like to admit about myself, except in the company of very close and trusted relations, is that over the past few years I have become increasingly obsessed with the prospect of death, and regularly consumed by the terror of it.

As the influence of my parents’ Catholicism has ebbed over time and drifted into the resignation of a mostly unspoken atheism, the gravity of that change has slowly come into focus: Someday I will be dead, and my subjective self lost forever. That same fact holds true for all of us, and eventually for the prospect for any life, anywhere. Over time, the universe will eventually rend itself apart, piece by piece, one final prolonged act of atomic torsion borne out over the course of eons. When all is said and done, we won’t just be gone; any trace of us will as well.

Reflections

I have stated my own desire to live forever—to experience infinite being, consciousness, and bliss—in many posts and in my most recent book on the meaning of life. As I’ve said many times I believe that death is an ultimate evil and should be optional. Thus we should strive to enhance and preserve human and post-human consciousness. I also agree that the fear of death is the source of much of the evil in the world. I do recognize that this desire for immortality may be narcissistic, and that we do best to overcome the fear of death by realizing that we are not that important and that life will go on without us. We need to allow the walls of our ego to recede as Bertrand Russell taught me long ago. Still death is such a waste of consciousness, and in an ideal world we wouldn’t need to be resigned to our extinction, to nothingness.

I’ll finish with a moving quote by that wonderful African-American novelist James Baldwin. It captures some of the deepest feeling I have about death.

Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage, 1992).

September 24, 2014

Black Holes and Political Ignorance

My vacation is over and readers should again expect regular posts. This is my 200th post.

The reaction among some American politicians to the recent news that black holes might not exist again reveals how either morally corrupt or scientifically illiterate they really are. In The New Yorker American Congressional Representative Michelle Bachmann (R-Minnesota) says this recent news reveals “the danger inherent in listening to scientists, adding “Actually, Dr. Hawking, our biggest blunder as a society was ever listening to people like you … If black holes don’t exist, then other things you scientists have been trying to foist on us probably don’t either, like climate change and evolution.” She concludes: “Fortunately for me, I did not take any science classes in college.” (Big surprise there!) Her views were echoed by Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), Chairman of the House Science Committee, who said, “Going forward, members of the House Science Committee will do our best to avoid listening to scientists.” (Avoid your physician sir!)

That such intellectual lightweights take aim at intellectual giants is an egregious violation of any standard of human decency. Those who have never taken a science class and never done any serious thinking in their lives have the nerve to criticize those whose abilities and effort led them to the pinnacle of their professions. What kind of world do we live in? How is it the inferior criticize their intellectual superiors, people report what they say, and others listen to them? Its enough to makesone embarrassed to be human.

Needless to say anyone who understood anything about science or its method would know that its conclusions are provisional–open to revision based on further evidence. Science does not accept something simple shepherds believed in the Eastern Mediterranean two thousand years ago, and then never change their minds. Moreover, the scientifically literate recognize that some parts of science, like theoretical cosmology, are more open to revision than basic biology, chemistry or physics. Of course its possible that the above politicians aren’t really ignorant but actually understand science and just lie for political gain. In that case they are not illiterate but immoral. In the two examples above I’d bet on their being scientifically illiterate.

But at least these science denying politicians can save money when they get sick, since they won’t go to the medical doctor who utilizes all that science. Ms. Bachmann is welcome to visit her local faith healer or medicine man. She is also welcome to reject aeronautical engineering the next time she is flying. She can calmly inform the pilot to turn off the engine, get her fellow passengers to hold hands and sing “up, up, and away.” We will see how that works. As for me, I’ll trust the science.

This would be all funny if it weren’t so sad. The middle ages and its superstition might return if these (mostly) Republican politicians have their way. This short video from comedy central last night makes this tragedy painfully obvious. (The most important segment begins at about 3 minutes into the video. )

September 12, 2014

My Wife’s 60th Birthday

On September 12th, 1954 a little girl was born in south St. Louis. One little girl born in one hospital, in one city, on one planet, at one precise moment in the vastness of space and time. A miraculous occurrence that made the world better and more beautiful. Simple words to describe what happened when Jane was born–goodness and beauty increased in the world.

But Jane didn’t keep this goodness and beauty to herself—she shared it by loving. Everyone who has ever touched or been touched by Jane has felt the warmth of her love. The circle of her love and concern begins with family but extends to the whole world. If the world was full of her kind, how beautiful it would be. She is a shining star in a dark world, she is incorruptible, she is impossible not to love.

I don’t know if my love for my wife is important in the whole scheme of things. I don’t know if anything is. But I do know that my life is richer and happier and less lonely and more joyful because of her. And I know that all who have truly known her feel the same way. And I know the world needs more like her because love is the only thing that will ever make life good and beautiful. And I know that uniting her soul long ago abolished my separateness; what began as a glance has lasted a lifetime. I was blessed.

Still my words are powerless to express the love I have for her. Maybe I can say it in a song.

September 3, 2014

On Vacation

To my regular readers

I have not written for the past few days as I have been preparing for two university courses I am teaching in the fall. I have also decided to take a few weeks off now so that my vacation overlaps with my wife’s. I should resume in about 3 weeks.

In the meantime I suppose the world will continue to burn. Here’s to hoping I’m wrong.

JGM

August 28, 2014

The Relevance of Philosophy

Nicolas Kristof’s recent New York Times column, “Don’t Dismiss the Humanities,” raised a topic of frequent discussion for one who has spent over 40 years studying philosophy. Kristof asks: “What use could the humanities be in a digital age?” And he answers the question immediately:

University students focusing on the humanities may end up, at least in their parents’ nightmares, as dog-walkers for those majoring in computer science. But, for me, the humanities are not only relevant but also give us a toolbox to think seriously about ourselves and the world.

I wouldn’t want everybody to be an art or literature major, but the world would be poorer — figuratively, anyway — if we were all coding software or running companies. We also want musicians to awaken our souls, writers to lead us into fictional lands, and philosophers to help us exercise our minds and engage the world.

Kristof notes how he was influenced by my own beloved discipline: “Skeptics may see philosophy as the most irrelevant and self-indulgent of the humanities, but the way I understand the world is shaped by three philosophers in particular.” Those philosophers are:

Isaiah Berlin, from whom he learned that the world is nuanced and complex, but that this shouldn’t paralyze us so much that we fail to act. We should not become like those pilloried by Yeats: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” We have doubts, yet we must act. As Berlin put it: “Indeed, the very desire for guarantees that our values are eternal and secure in some objective heaven is perhaps only a craving for the certainties of childhood.”

John Rawls who wrote the most celebrated work of ethical and political theory in the twentieth century, A Theory of Justice. In it Rawls argues for what he calls “justice as fairness,” which reconciles the competing values of liberty and equality. Rawls invites us to choose our moral principles from behind an impartial “veil of ignorance,” which prevents us from knowing anything about who will be in society. From this “original position” Rawls thought that self-interested individuals would choose a fair system. If we don’t know whether we’ll be rich or poor, black or white, male or female, we are apt to favor a system that distributes the wealth of society quite equally. And finally Peter Singer, who has argued that we should treat non-human animals much better than we now do.

Kristof concludes:

So let me push back at the idea that the humanities are obscure, arcane and irrelevant. These three philosophers influence the way I think about politics, immigration, inequality; they even affect what I eat.

It’s also worth pointing out that these three philosophers are recent ones. To adapt to a changing world, we need new software for our cellphones; we also need new ideas. The same goes for literature, for architecture, languages and theology.

Our world is enriched when coders and marketers dazzle us with smartphones and tablets, but, by themselves, they are just slabs. It is the music, essays, entertainment and provocations that they access, spawned by the humanities, that animate them — and us.

So, yes, the humanities are still relevant in the 21st century — every bit as relevant as an iPhone.

Reflections

As one who has taught both computer science and philosophy majors during my career, I must say that I unhesitatingly advised students with aptitude in both subjects to major in computer science. Unless one is independently wealthy, it is too risky for a student to major in philosophy in the USA. (I would guess this holds around the world as well.) Moreover one can major in computer science, engineering, or related fields and still be informed by philosophy. So I will continue to tell my students not to major in philosophy, unless some new social and economic system arises in which persons can make a good living while philosophizing.

Of course this is a different issue than whether philosophy or the other humanities are worthwhile. Of course they are! We are not fully human unless we know something of philosophy, literature, history, music, religion and art. Surely the world needs informed people who can engage in rational discourse, in Socratic dialogue. Surely we need more people to admit, like Socrates, how much they don’t know.

Most of all, as Kristof notes, we need new ideas. And as I’ve told my students for years, ideas are important—they are not something confined to the ivory tower. Ideas incite revolution and war, they move people to sacrifice themselves, they change science and technology. Ideas change the world. And ideas come from the most unlikely of places, including the humanities. For ultimately the humanities are outgrowths of the human condition, of our need to understand truth, beauty, goodness justice, meaning and more. The study of the humanities paves the way for making us more humane.

August 27, 2014

Truth and Justice

In a previous post I promised to discuss two great ideas—truth and justice. A lifetime of study wouldn’t suffice to properly discuss these two ideas, but I wanted to offer something.

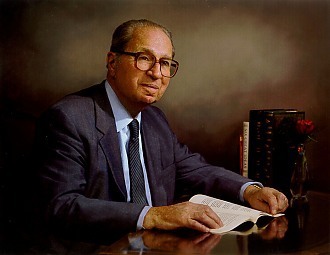

There are many great ideas. The philosophical popularizer of last century, Mortimer Adler, wrote a massive tome entitled: THE GREAT IDEAS: A SYNTOPICON OF GREAT BOOKS OF THE WESTERN WORLD, VOLUME II, MAN TO WORLD (1952). It contained 102 great ideas which Adler later paired down to six in his book, Six Great Ideas (1981)

(1952). It contained 102 great ideas which Adler later paired down to six in his book, Six Great Ideas (1981) .

.

Those six were: truth, beauty, goodness, liberty, equality, and justice. Adler distinguished these in triads: truth, beauty, and goodness are ideas we judge by; liberty, equality, and justice are ideas we act on. I think the organization of the triads is illuminating.

1. Truth

Adler holds that truth is the sovereign idea by which we judge. He believes that beauty is a special kind of goodness, which is itself a special kind of truth. He also holds that truth—by distinguishing certain from doubtful judgments, and by differentiating matters of taste and matters of truth—provides the ground for understanding beauty and goodness. Whether this is true or not I’ll leave for the reader to consider.

Yet there is something intuitively plausible in this analysis. If we know what’s true, we would know what was truly good and beautiful. (This depends on the Adler’s acceptance of philosophical realism and a correspondence theory of truth.) But knowing what’s good or beautiful does not seem to entail that we know what’s true—the relationship is not symmetrical. Thus truth seemingly regulates our thinking about goodness and beauty; it is the one to which the other two are subordinate. And, as I’ve stated many times, if the truth isn’t important, then nothing much else is either. Truth is surely one of the greatest ideas.

2. Justice

As for the ideas we act on, justice reigns supreme. Here I find Adler’s argument especially compelling. He argues that justice is an unlimited good, while liberty and equality are limited goods. The distinction comes from Aristotle. Limited goods are goods we can have too much of, while we cannot have too much of an unlimited good. Societies can have too much liberty or equality, but not too much justice.

The argument is straightforward. For political libertarians, liberty is the highest value and they seek to maximize liberty at the expense of equality. They want near unlimited liberty even if the result is irremediable inequality, and even if large portions of society suffer serious deprivations. They may favor equality of opportunity, knowing that those with superior endowments or favorable circumstances will beat their fellows in the race of life. The resulting vast inequality doesn’t deter them, for in their view trying to achieve equality will result in the loss of the higher value, liberty. On the other hand, egalitarians regard equality as the highest value and willingly infringe upon liberty to bring about equality of outcomes. In their view equality of opportunity will not suffice, since that will still result in vast inequality, the supreme virtue in their eyes.

The solution recognizes that liberty and equality are both subservient to justice. An individual should not have so much freedom of action that they injure others, deprive them of their freedom, or cause them other serious deprivations. One should only have as much freedom as justice allows. Analogously, should a society try to achieve equality of outcomes even if that entails serious deprivations of human freedom? Should we ignore the fact that individuals are unequal in their endowments and achievements? No says Adler to both questions. We should only have as much equality as justice allows.

Regarding liberty, justice places limits on the amount allowed; regarding equality, justice places limits on the kind and degree it allows. Thus justice is the sovereign idea among those that we act on—it places limits on the subordinate values of liberty and equality. Too much of either liberty or equality results in an unjust society. I agree with Adler, justice is the ultimate idea of moral and political philosophy.

August 26, 2014

How Should We Spend Our Time?

I have promised posts on the topic of “truth and justice” and “cognitive bias.” I will deliver in the next few days on the former topic, but I won’t have time for the latter. (For those interested, two sites about cognitive bias are: Overcoming Bias, the blog of Professor Robin Hanson of George Mason University, and Less Wrong, the brainchild of Eliezer Yudkowsky, a researcher at Machine Intelligence Research Institute.)

Speaking of a lack of time, today, as I was reading multiple threads on multiple topics by members of the research group with whom I’m affiliated, (Evolution, Complexity and Cognition Group in Belgium) I was struck by the importance of deciding what one will read, think, and do in one’s lifetime. Why? Because there is too much material to read and think about for any one person to be acquainted with, much less master. It would be a full-time job just to digest all the material on my email threads. Moreover, at the moment there are at least 20 topics in my blog post que, and ten books waiting to be read. It is overwhelming. One must pick and choose, so that one doesn’t waste their precious time on triviality. Life is short. But according to what criteria do we pick and choose?

My main criterion is to pursue, as far as possible, timeless topics like the meaning of life and love, the importance of truth and justice, the advancing science and technology, and the course of cosmic evolution. Obviously these topics are themselves much too broad–one is going to have to specialize further to make much progress. Still I remember reading Isaac Asimov’s advice that we eschew specialization so that we can be polymaths. I think there is much to this. If our focus is too narrow, we miss the proverbial forest for the trees. Nonetheless no advice is truly adequate here. There is an almost infinite amount of existing knowledge which increases daily, and our minds are finite. As I’ve said many times our best hope for synthesis of this knowledge is to increase our mental capacities. Until then I would advise thinking about as many timeless things as possible while maintaining physical vigor and mental health.

In addition to intellectual life, there are also obligations to family, to making a living, to bettering the world, and more. Here too we must make choices—there are more things to do than we can do. But we should do what we generally enjoy, with the caveat that we are bad at predicting our own happiness. Still life is too short to make ourselves and others miserable by pursuing some supposed, but despised, duty.

In the end we must strike a balance. This idea was well captured in the opening pages of An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. There, David Hume penned this remarkable paragraph:

Man is a reasonable being; and as such, receives from science his proper food and nourishment: But so narrow are the bounds of human understanding, that little satisfaction can be hoped for in this particular, either from the extent of security or his acquisitions. Man is a sociable, no less than a reasonable being: but neither can he always enjoy company agreeable and amusing, or preserve the proper relish for them. Man is also an active being; and from that disposition, as well as from the various necessities of human life, must submit to business and occupation: but the mind requires some relaxation, and cannot always support its bent to care and industry. It seems, then, that nature has pointed out a mixed kind of life as most suitable to the human race, and secretly admonished them to allow none of these biases to draw too much, so as to incapacitate them for other occupations and entertainments. Indulge your passion for science, says she, but let your science be human, and such as may have a direct reference to action and society. Abstruse thought and profound researches I prohibit, and will severely punish, by the pensive melancholy which they introduce, by the endless uncertainty in which they involve you, and by the cold reception which your pretended discoveries shall meet with, when communicated. Be a philosopher; but, amidst all your philosophy, be still a man.

August 22, 2014

Being A Deep Person

Yesterday’s post advocated for personal growth, the means by which humanity’s desperate need for better people might be satisfied. Today I read an article in The Atlantic that provided additional insight into the topic. It summarized a talk given by the conservative New York Times columnist David Brooks at the 2014 Aspen Ideas Festival. Normally I agree with almost nothing Brooks says, but here I found his thinking insightful.

Brooks argues that American culture overemphasizes attaining happiness, rather than “a different goal in life that is deeper than happiness and more important than happiness.” We focus on power, wealth, and professional success, instead of cultivating the kind of personal qualities that will be discussed at our funerals. As Brooks says, we put “resume virtues” over “eulogy virtues.” Instead of emphasizing happiness and resume virtues, we should search for inner depth, for eulogy virtues.

For Brooks, the American rabbi and philosopher Joseph Soloveitchik captured the dichotomy between resume and eulogy virtues in his book, The Lonely Man of Faith . In it Soloveitchik differentiates between “Adam I” and “Adam II.” As Brooks explains:

. In it Soloveitchik differentiates between “Adam I” and “Adam II.” As Brooks explains:

Adam I is the external Adam, it’s the resume Adam … Adam I wants to build, create, use, start things. Adam II is the internal Adam. Adam II wants to embody certain moral qualities, to have a serene inner character, not only to do good but to be good. To live and be is to transcend the truth and have an inner coherence of soul. Adam I, the resume Adam, wants to conquer the world … Adam II wants to obey a calling and serve the world. Adam I asks how things work, Adam II asks why things exist and what ultimately we’re here for … We live in a culture that nurtures Adam I … We’re taught to be assertive and master skills, to broadcast our brains. To get likes. To get followers.”

But how do we nourish depth? What does it even mean to be deep? Brooks says:

I think we mean that that person is capable of experiencing large and sonorous emotions, they have a profound spiritual presence … In the realm of emotion they have a web of unconditional love. In the realm of intellect, they have a set, permanent philosophy about how life is. In the realm of action, they have commitments to projects that can’t be completed in a lifetime. In the realm of morality, they have a certain consistency and rigor that’s almost perfect.

Brooks also thinks deep people tend to be old, and I agree. “The things that lead you astray, those things are fast: lust, fear, vanity, gluttony … The things that we admire most—honesty, humility, self-control, courage—those things take some time and they accumulate slowly.” He lists: Albert Schweitzer, Dorothy Day, Pope Francis, and Mother Teresa as examples of deep people.

Objections

Although I do believe we ought to become deeper people, I object to much of Brooks’ characterization of depth. “Large and sonorous emotions” and “spiritual presence” often hinder a life of depth. The Stoics and Buddhists believed (roughly) that fervent emotions impede a good life, and no one can accuse either group of not being deep. As for spiritual presence, the notion is extraordinarily vague. Perhaps Brooks uses the term to describe deep feelings generally. I’m not sure. But I can say unequivocally that strong emotions and religious attachments often fetter personal growth.

“A set, permanent philosophy” can also be a hinderance to depth. If this philosophy results from a lifetime of serious searching and impartial inquiry, then it is a sign of depth. But in the vast majority of cases a set, permanent philosophy is the first one to which the individual was exposed, which is practically the opposite of being deep. Also, an unreflective, permanent acceptance of the first philosophy to which one has been exposed often leads to dogmatism. And a dogmatic, unreflective person is essentially the opposite of a person of depth.

I agree that persons of depth often have “commitments to projects that can’t be completed in a lifetime,” but so too do Nazis, fascists, and Fox News anchors. Being committed to tyranny, oppression, slavery, or racism does not make you a deep person. Or if it does, it surely doesn’t make you a moral one. Yet Brooks says, “In the realm of morality, they [deep people] have a certain consistency and rigor that’s almost perfect.”

This is the fundamental flaw in Brook’s description. We can imagine the most committed Nazi, slave owner, exploitative capitalist or Fox News pundit having deep, spiritual-like emotions about philosophies which they consistently hold, and which they hope will continue on after their lifetimes. But few of us would call such people deep or moral.

This suggests that Brooks analysis only works if morality as ordinarily understood is not part of a deep life. By “morality as ordinarily understood,” I’m thinking of the late philosopher James Rachels’ account, in his best-selling university textbook, of “the minimum conception of morality.” The generally agreed-upon starting point for any moral philosophy is: 1) an effort to guide one’s conduct by reasons; and 2) giving impartial consideration to the interests of each individual who will be affected by one’s conduct. Needless to say the committed Nazi and their ilk do not subscribe to this minimum conception. Thus Brooks idea of depth doesn’t preclude the immoral, as surely he intended it to do.

The implications of Brooks’ view would also come as a surprise to Buddhists who advocate loving kindness, or to religious traditions which advocate beneficence, or to the majority of moral philosophers who believe that compassion for and connection with our fellows is a large part of being “deep.” Yes, you could talk about intellectual or aesthetic depth without reference to morality, but I don’t think this is the depth Brooks has in mind.

I also object to Brooks brief list of deep persons. It’s hard not to notice that three of the four persons he mentioned are Catholics. (Albert Schweitzer was not Catholic and rejected much of traditional Christianity. Still he might be called a Christian mystic or a death-of-God theologian.) Combined with Brooks’ references to “spiritual presence,” this suggests that he thinks depth may be related with religion. The objections to this line of thinking are so apparent they hardly need noting. I am not saying a religious person cannot be a deep, moral person, but I am saying there is not a shred of evidence that suggests the religious persons are any deeper than the secular ones. I actually think that conventional religion is generally an impediment to depth and morality, although this claim would take defending. (As an aside, critics have claimed that Mother Theresa was no moral exemplar. )

Reflections

I have noted some strong objections to various aspects of Brooks thinking. Yet for the most part I agree with his overall sentiments. The deep, moral life is the one most worth living, and we generally do not cultivate or value the search for it. Such a life can be found in many ways: taking care of your children, doing relatively menial work, singing, dancing, playing, creating, or in some combination of activities. As for happiness, when directly sought is often missed. Rather it is the unintended by-product of a life explored as far as possible to its depth. Seek to live deeply, morally, and meaningfully, and you will have the best chance of living well.

A Final Caveat

I do realize how trite the above advice is for those who are destitute, incarcerated, oppressed, etc. As I’ve said many times, following Aristotle, one needs a good government to have a good life—the good life cannot be achieved by individual effort alone. Aristotle didn’t think that government could make people virtuous or happy, but good government by definition must provide the conditions under which all its citizens can flourish. This is how adjudicate between good and bad governments. Judged accordingly, the US government is better than some African governments, but much worse than any Scandinavian government or almost any European government at providing the conditions in which all people can flourish.

For those who are systematically oppressed I have little to offer, except to advise you to do your best to find some opportunity in the injustice which surrounds you. That it surrounds you is a great stain on all of us, and our more advanced descendents will look back with horror that we tolerated so much injustice. It makes me ashamed of being human. Please accept my apologies along with most fervent wishes that you find inner peace nonetheless.

August 21, 2014

The World Desperately Needs Better People

Received an unusually thoughtful correspondence from a reader who has become interested in intrinsic rather than extrinsic reward. The reader was an unusually high achiever who began college with a full scholarship to one of the nation’s most prestigious universities at the age of 14, and who graduated as one of the most decorated graduates of another of the world’s prestigious university. Despite earning a salary in her late twenties that would make many mid-career physicians blush, she seemed dissatisfied. Was her work valuable, meaningful, fulfilling? She thought not. So she resigned her position with one of the world’s best companies to take time off to raise her young daughter. (Don’t say she is “just” a mother.) Here is what she wrote:

Its one of the things [intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation] I had time/space to reflect on in my time off. Why did I do tech for 10 years? Certainly not because we live a bmw-driving, million-dollar-house-living, world-traveling, stuff-buying lifestyle that required it. It was/is because money and a job title are a form of “grades” and without them I felt worthless. But, now that I realize it, I have the ability to define [my life] on my own terms, which will be challenging but [which will allow for the possibility of] growth.

This is extraordinarily profound thinking which needs unpacking. As for intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation, all I know is that I was never motivated by extrinsic reward, and I know many others who are not. When I was first married with a new baby on the way, I was encouraged to become a computer programmer. This was sound advice. The field was burgeoning and I had mathematical/logical aptitude. But I had no intrinsic motivation to learn it.

When I went back to graduate school when I was thirty, I gave up making quite a bit of money as a casino dealer. What was the point of dealing cards all day no matter how good the tips were? I just didn’t want to spend my life that way. I wanted to do graduate work in philosophy; that’s what I had always wanted to do. I didn’t want to die and know Buddha’s or Aristotle’s names, but not their philosophies. In fact I think most of us do best what we really want to do. If you want to be a good golfer, play guitar, build things, learn psychology, know music or make a lot of money, then you will are intrinsically motivated to do those things. And will probably do them well. There is little doubt. We are best motivated by the intrinsic rewards we get for doing what want to do.

Of course the chance to do what we want to do rather than what we have to do depends in large part on whether we live in a society which provides an opportunity for all its citizens to flourish—which is what makes a society a good one. But if one is lucky enough to have the opportunity and ability to define their lives as they want—then they should seize the moment, accept the challenge and grow. The world so needs people who have grown, who have evolved, who have increased their awareness. The world desperately needs better people more than it needs anything else. To those embarking on this journey I say—go forth and travel.

August 20, 2014

Motherhood

The Author

Kieran Snyder (Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania) has spent the last decade leading teams of software designers and engineers. She is also a mother and she has written two recent articles for Slate magazine. (Where does she get the time?) Here is her description of those articles:

Last week I published an article in Slate that looked at gender and conversational interruptions in preschoolers. It was a follow-up to an earlier article I’d published, also in Slate, about gender and conversational interruptions in the corporate tech setting. Taken together, the two mini-studies draw a line between the girls who learn not to interrupt in childhood and the frequently interrupted women that they become.

Hate Mail Regarding the Follow-Up Article

She has also written a recent follow-up piece to those articles in response to some particularly negative comments she received. Ms. Snyder notes:

The corporate tech article had many thousands of Facebook shares, significant Twitter activity, and lots of discussion around town … Most of the several hundred direct messages that I’ve received about it have been encouraging …. The children’s article has had much less pickup. Although the topic and dataset are quite similar to the tech study, fewer readers have discovered it, and those that have are mostly not sharing it the same way …

Yet, despite being less widely circulated, the article on children has generated hate mail! She has been called: “a dumb mom who should go back to playgroup; a bitch who should learn to shut up; just another dumbass mom who thinks she’s a “scientist;” and more. She notes that these are not questions about methodology or the sample size–reasonable concerns she agrees–but specific attacks on her as a mother. For example: “As loath as I am to given much credence to the “data” compiled by a mom with a vested interest in the topic watching her kids play; or, It’s bad enough so many of these things we read about are based on small scale studies of college students motivated by extra credit, now we have parents doing “studies” on their kids. Too bad this woman’s ego outweighs her professionalism.” On hearing all this I immediately went to the article and was amazed by how tame it was. What could evoke such a reaction?

She specifically notes that there is much criticism of the anecdotal nature of her data regarding preschoolers, but none regarding the women in tech article. This despite the fact that, “The datasets for both articles are quite similar and have similar weaknesses. If anything, the child dataset is somewhat stronger because some of it is validated by an independent judge.” A major difference between the two articles is that the article about pre-schoolers “highlight[s] the fact that I am a mother several times throughout the article.”

Her Response

Could it be that her being a mother is the source of much of the vitriol? Perhaps. As Snyder says: “People hear tech and they think interesting.People hear mother and think go back to playgroup.” Maybe that explains a reader who calls her a “dumbass mom who thinks she’s a “scientist.” But why do many readers make the connection between mother and professionally unqualified? Snyder suggests “It’s probably for the same reason that the tech industry where I work famously asks people, “But would it work for your mom?” as a way to evaluate whether a product design is acceptable for unsophisticated users.” (This is particularly amusing in our family. I’m a humanities scholar who can barely turn my computer on, while my wife is a senior database developer with an M.S. in mathematics. My kids, who work in software, say “Would it work for dad?”)

Snyder notes that she is proud of being a mom, just as she is proud of being a linguist, and of her software career and marathon running. Besides being a mom, contrary to the critics, doesn’t detract from or invalidate her other accomplishments:

… becoming a mom made me better at my job, not worse. I am a better manager in terms of both delegation and empathy. I have less time, so I prioritize more effectively. That benefits me, the individuals on my team, and the business overall … Becoming a mom has also developed my specific professional interests. Like the way that having a kid of my own has taken me back to my roots in empirical linguistics and child language development, which has in turn led me to apply those same statistical techniques to studies of gender in the tech workplace where I spend most of my time.

She concludes by noting that,

Moms I know who have left corporate tech careers to raise their children include public advocates for the Chicago school system, journalists winning awards for their coverage of domestic abuse, and founders of educational nonprofits. All of them have taken their professional skills and applied them in domains motivated heavily by their motherhood. Any one of them has enough rigor to take your “dumbass mother” and shove it.

Reflections

Regarding the data itself, the criticisms are unfounded. Snyder states that “The data here is only directional, and as with the adults in tech study, needs further investigation.” That is a significant and conscientious disclaimer. Nonetheless the results of her careful observations are to be reckoned with. We might also remember that Jean Piaget’s groundbreaking theories of cognitive development—probably the most famous ever done—were developed after “careful, detailed observations of children. These were mainly his own children and the children of friends.”

Regarding the disparaging remarks about motherhood, we must be careful. There are racists, bigots, misogynists, and more in this world. Hatred seems to be an essential element of our existence. In this case, I would guess that the confluence of at least three factors explains the different reactions to Snyder’s two articles.

First is misogyny. For reasons that would take a dissertation to flush out, many men see women as … well you know. The biological and cultural roots of these attitudes are, to say the least, complicated. Moreover, that a woman is better at something than they are just annoys some men. Jealousy is also endemic to the human condition. Snyder has a PhD from Penn and has worked in some of the best high-tech companies in the world–enough to make the most talented man jealous, and some other women too. But there is no doubt something leftover in the mammalian male brain from millions of evolution that predisposes men to more aggressive talk and behavior.

The other reason is probably motherhood. In the contemporary Western world we often make the assumption that full-time mothers are not as smart or ambitious as career women. If a woman could make a six-figure income at work, why would she stay at home? The conclusion many draw is that she can’t make such an income, although that is obviously not true in Snyder’s case. In the US today, the role of motherhood and parenting has relatively little prestige compared to making a large income. (Why and how and if this has changed through time goes beyond the scope of this essay.) At first glance though I surmise that something about consumerism and materialism plays a role in denigrating parenting in general.

The final and most important reason for the heated responses to Snyder’s post probably has to do with what I’ve been writing about in my recent posts–people’s inability to believe what they don’t want to believe. If I don’t like the implications that follow from little boys interrupting more than little girls—boys should cease and desist?—then I’m not going to believe it. I’m not sure what follows from Snyder’s very mild observations but some, probably men, were threatened. When our cherished beliefs are threatened, most of us dig in.

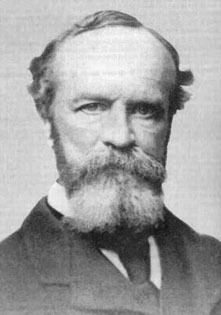

All this reminds me of a quote from William James, which I long ago committed to memory. “As a rule we disbelieve all the facts and theories for which we have no use.”