John G. Messerly's Blog, page 141

July 10, 2014

Carl Sagan & Human Survival

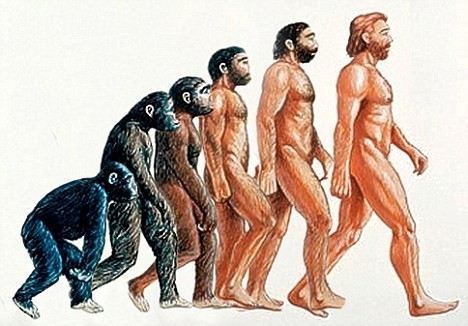

In the final episode of Cosmos (Who Speaks for Earth?) Carl Sagan wonders whether our species will survive.

In our tenure on this planet we’ve accumulated dangerous evolutionary baggage: Propensities for aggression and ritual submission to leaders, hostility to outsiders. All of which puts our survival in some doubt. But we’ve also acquired compassion for others, love for our children, a desire to learn from history and experience and a great, soaring, passionate intelligence. The clear tools for our continued survival and prosperity. Which aspects of our nature will prevail is uncertain.

Sagan argues that the problem arises because our vision is too small. We lack a cosmic perspective from which national, ethnic and religious fanaticism are difficult to maintain. Perhaps such fanaticism has destroyed the civilizations on other worlds, as the Spanish destroyed those of the new world. Perhaps other civilizations have destroyed themselves with their technology, as we will do to our own in the near future. Or perhaps we will poison our air, earth, and water, fall victim to viruses and bacteria, or change our fragile climate so as to bring out our extinction. Then “There would be no more big questions. No more answers. Never again a love or a child. No descendants to remember us and be proud. No more voyages to the stars. No more songs from the Earth.” We would have ceased to listen to our compassion and reason, heeding instead to the reptilian voice of fear, territoriality and aggression.

From an extraterrestrial perspective, our global civilization is clearly on the edge of failure in the most important task it faces: Preserving the lives and well-being of its citizens and the future habitability of the planet … Shouldn’t we consider … A fundamental restructuring of economic, political, social and religious institutions?

And while change is often labeled impractical, Sagan reminds us that changes have been made. We have reduced significantly slavery since ancient times, women have been partially liberated, aggression has been somewhat curtailed, and we have begun to see the earth as an organism in need of our stewardship. We can now see the earth from a cosmic perspective “finite and lonely somehow vulnerable, bearing the entire human species through the oceans of space and time.” We can change; and we have survived. After a 14 billion year cosmic journey carbon has become people, starstuff has been animated, and the cosmos is becoming conscious of itself.

Still, we do not know our place in the vastness of space and time. It will be found only after a long and arduous journey made by sojourners unafraid of the truth when they encounter it. As the video above so movingly concludes.

And we we who embody the local eyes and ears and thoughts and feelings of the cosmos we’ve begun, at last, to wonder about our origins. Star stuff, contemplating the stars, organized collections of 10 billion- billion-billion atoms contemplating the evolution of matter tracing that long path by which it arrived at consciousness here on the planet Earth and perhaps, throughout the cosmos. Our loyalties are to the species and the planet. We speak for Earth. Our obligation to survive and flourish is owed not just to ourselves but also to that cosmos, ancient and vast from which we spring.

If only our vision could be as large as Carl Sagan’s.

All trademarks mentioned herein belong to their respective owners.

July 9, 2014

Philosophers are Rarely Anti-Abortion

Philosophers and Abortion

I have never addressed an applied ethics issue in this blog, although I have taught approximately 100 sections of university ethics courses. However, a recent reader’s comment that included abortion in a list of great moral wrongs prompts this brief response.

Let me say first that among professional philosophers it is quite rare to find a so-called pro-lifer. I can’t find statistics online on applied ethics issues, While statistics can be found about professional philosophers’ theoretical positions–for example that less than 15% of professional philosophers are theists–statistics about their views on applied ethics issues are not readily available. But I would guess that around that around 10% of professional philosophers defend the so-called pro-life position. I base this on the fact that in my entire teaching career at multiple universities I have never personally known a single non-religious philosopher to take this position, but I have known many religious philosophers to take the opposing view. For further support about how rare the anti-abortion sentiment is among professional philosophers consider the opening lines of the most celebrated anti-abortion piece in the literature–one that is reprinted in virtually every university ethics text:

The view that abortion is, with rare exceptions, seriously immoral has received

little support in the recent philosophical literature. No doubt most philosophers

affiliated with secular institutions of higher education believe that the anti-abortion position is either a symptom of irrational religious dogma or a conclusion generated by seriously confused philosophical argument.1

The pro-life position among professional philosophers is rare indeed. Again, among the secular minded the view that abortion is seriously wrong is practically non-existent, despite the fact that killing, torture, lying, cheating, stealing, and more are nearly universally condemned by secular and non-secular philosophers alike. Now why is there such unanimity regarding the abortion issue among professional philosophers?The reason is that they professional philosophers generally find the anti-abortion arguments philosophically suspect if not worthless.

Anyone interested in the topic can read a sampling of the philosophical literature to find the devastating critiques of the conservative view–the one that grants the fetus full moral rights from conception. (There actually is no “moment” of conception, but that’s a different issue.) At best a philosopher might grant that, while it may be morally praiseworthy to continue an unwanted pregnancy, it is in no way morally obligatory. You are not morally required to be a good Samaritan in Judith Jarvis Thomson’s language, or be held captive by aliens so as to bring about other lives in Mary Anne Warren’s thought experiment. As for me, I unequivocally support the contemporary philosophical consensus–abortion is almost never morally problematic. The primary reason for this is that the evidence and rational arguments are nearly definitive–the fetus is not a person with full moral rights. However, as Jane English has pointed out, even if it were killing the conceptus is not always wrong. There is a lot more to say about this, but I have neither the time nor inclination to discourse further on the philosophical aspects of the issue. Again for those interested, the philosophical literature on the topic is easy to find.

Christianity and Abortion

While it is true that most professional philosophers do not find abortion morally problematic, what about Christian theologians? I really don’t know or care to know much about the views of theologians, but certainly many Christians think they must oppose abortion on religious grounds. But must they? The answer is no for a number of reasons.

First, it is generally hard to find specific moral guidance in religious scriptures. They were written long ago, survived as oral traditions, have been translated multiple times, and are open to multiple interpretations. (Anyone who has ever translated languages knows that literal interpretations are impossible.) Moreover, church traditions are ambiguous on many moral issues.

The key idea of the conservative view is that the fetus is a person with full moral rights from “moment” of conception. Most philosophers deny this claim because the necessary or sufficient conditions of personhood are notoriously difficult to ascertain and, at any rate, the fetus does not satisfy many of the conditions. The impartial view, backed by contemporary biology, is that a fetus is, at most, a potential person. But allowing for the sake of argument that the conservative view is the Christian view, then this must be supported by either church tradition or church scriptures. But is it?

It is well-known that it is difficult to derive a prohibition of abortion from Christian scriptures, since the issue does not arise in the Christian scriptures. There are a few Biblical passages quoted by conservatives to support the anti-abortion position, the most well-known is in Jeremiah “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you.” But, as anyone who has examined this passage knows, the sanctity of fetal life is not being discussed here. Rather Jeremiah is asserting his authority as a prophet. (This is a classic example of seeking support in holy books for a position you already hold.)

Many other Biblical passages point to the more liberal view of abortion. Three times in the Bible (Genesis 38:24; Leviticus 21:9; Deuteronomy 22:20–21) the death penalty is recommended for women who have sex out-of-wedlock even though killing the women would kill their fetuses. (I don’t think death is recommended for men since they wrote the book.) Furthermore, in Exodus 21, God prescribes death as the penalty for murder, whereas the penalty for causing a woman to miscarry is a fine. In the Old Testament the fetus does not seem to have personhood status. Thus there is no strong scriptural tradition in Christianity against abortion.

There also is no strong church tradition against abortion. The idea that the fetus is a person from the moment of conception is quite new in church tradition. St. Thomas Aquinas, the preeminent thinker in Catholicism, held that embryo didn’t acquire a soul into several weeks into gestation–after the embryo had a human form. This position was officially accepted by the church at the Council of Vienne in 1312.

However, in the 17th century, scientists peering through primitive microscopes at fertilized eggs thought they saw tiny, perfectly formed people–what they called a “homunculus,” or little man. Now if humans had a human shape from the moment of conception then it follows, from Aquinas, that it has a soul from the very beginning. This mistaken view of embryological development led to the Church changing its stand on abortion.

Of course we now know there is no homunculus. We know that embryos start out as a cluster of cells, and human form comes later. But when the biological error was corrected, the church did not revert to its earlier moral position. Instead it held to the position it holds to this day, that the soul enters the embryo from conception, even though this view is based on a false view of the biological facts.

The point of all this is not that the contemporary church’s position is wrong. For all I know, it may be right. My point is that the anti-abortion position follows no more from church tradition than it does from scripture. What really happens when people suppose that religion demands a moral view is that those people have moral views and then look to scripture or tradition to support the views they already hold. People’s moral convictions are not usually derived from their religion so much as superimposed on it. All of this suggests that morality is not based on religion but on reason and conscience. As Plato argued a long time ago in the Euthyphro, things can’t be right just because the gods command them, the gods must command them because they’re right. And if that’s the case then the gods have some reason for their commands, reasons that are intelligible to rational beings.

Thus we are led back to philosophical ethics. In the case of abortion, rational arguments either support the anti-abortion position or they do not. The vast majority of professional philosophers find those arguments seriously lacking. I agree. The arguments for the pro-life position are seriously deficient, while the opposing arguments are philosophically robust. On that basis I concluded years ago that abortion was almost never morally problematic.

Postscript - American Politics and Abortion

Here again there is much to say about the politics of all this. There is no doubt that much of the anti-abortion rhetoric comes from a punitive, puritanical desire to punish people for having sex. Many are also hypocritical on the issue, simultaneously opposing abortion as well as the only proven majors of reducing abortion–good sex education and readily available birth control. As for self-interested conservative politicians, their public opposition is obviously hypocritical. Generally they don’t care about the issue–they care about the power and wealth derived from politics–but they pretend to do so in order to throw red meat to their constituencies. And while they may be pro-birth, they clearly aren’t pro-life–in fact they vigorously oppose helping children after they are born by denying them adequate education, health-care, economic opportunities, and the like.

In the end rational discourse is the only violence free way to resolve moral controversies in a morally pluralistic society. To the extent they cannot be resolved, the political solution of American democracy has been to allow individuals to hold to their beliefs, but never to impose them on others unless clear harm was being done to others. (John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle.”) In the case of fetuses, the otherness cannot be established. Hence there is no justification to force your metaphysical beliefs about the moral status of an unknown conceptus on other persons choices.

1. Don Marquis. “Why Abortion is Immoral,” Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 86 (April, 1989), pp. 183-202.

July 8, 2014

Dogmatism & Scientific Ambiguity

The Church says the earth is flat, but I know that it is round, for I have seen its shadow on the moon, and I have more faith in a shadow than in the Church. ~ Ferdinand Magellan

As the video above suggests, those who proclaim to know the truth merely reveal their ignorance. We should be humble–especially metaphysicians but scientists too–about drawing definitive conclusions about perplexing topics. The universe is large and our brains are small. Yet our science should not be dismissed; it has given us the little knowledge we possess. To abandon it would set the human species back a thousand years. As Einstein said “All our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike–and yet it the most precious thing we have.”

So as we swing on a pendulum between belief and doubt, between certainty and skepticism, we should not lose faith. “Dare to know.” That, Kant said, was the motto of the Enlightenment. With arduous scientific searching, answers will continue to be forthcoming. In the meantime we should not despair. Let that great 20th century scientist Richard Feynman have the last word today.

I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of certainty about different things, but I’m not absolutely sure of anything, and many things I don’t know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we’re here, and what the question might mean. I might think about it a little bit, but if I can’t figure it out, then I go on to something else. But I don’t have to know an answer. I don’t have to…I don’t feel frightened by not knowing things, by being lost in the mysterious universe without having any purpose, which is the way it really is, as far as I can tell, possibly. It doesn’t frighten me.

July 6, 2014

Does the Number of Stars in the Universe Make Other Intelligent Life More Likely?

My recent post on the Fermi Paradox generated many comments on my site and many more on Reddit. I also had an interesting discussion with someone who made a startling claim, assuming I interpreted him correctly. The unimaginably large number of stars and planets does not increase the likelihood of their being intelligent life on other worlds!

The Fermi paradox is the apparent contradiction between the high probability of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence given the unimaginably large number of stars and planets in the cosmos, and the complete lack of evidence for extraterrestrial life. Hence Fermi’s question, “Where is everybody?”

Interestingly I have used this paradox for many years to introduce students to the idea of how certain I assent to various proposition. For example, I am about 99.99999% certain that human animals evolved from lower life forms over billions of years, given the overwhelming evidence for the proposition. And I am 99.99999% sure that there are no round squares or married bachelors anywhere in the cosmos, given that these can only be false if the basic principles of logic are mistaken. About many other issues I might feel 80 or 50 or 20% confident. I feel 50% confident that the next coin flip will be heads or tails. Regarding the existence of intelligent life on other worlds, I am agnostic. I just don’t know.

However I believe that the unimaginably large number of stars, planets, galaxies, (and perhaps universes themselves) makes the probability of life on other worlds more likely. It gives us a reason to believe that such life exists. This is self-evident. To see why consider the following. If we knew there were only 10 stars in the universe, as opposed to the nearly 400 billion in our galaxy alone, that fact would make the existence of otherworldly intelligent life less likely. The reason is that the less planets there are the less likely any one of them would sustain intelligent lie. For example, if 1 in 100 planets on average support life then in a universe of 100 planets we would expect life to exist on 1 of them. But if there were 400 billion stars with say 4 trillion planets and moons orbiting them, then we would expect 40 billion planets in our galaxy alone that would support life. (1% of 4 trillion.) And remember there are about 100 billion galaxies in the known universe so that would mean about 40,000,000,000 x 100,000,000,000 planets with intelligent life.

But my interlocutor questioned all this. Since we don’t know the probability of life arising on a given planet, he claimed, then whether there are 100 planets or 1024 makes no difference. (This assumes the 1023 stars in the observable universe each had 10 planets and moons orbiting them. This exponential of the number of planets would be written out like this 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.) His point was whether we multiply 10 or 1024 by an unknown quantity we don’t know what the result will be because we don’t know what we should multiply by. Moreover 10 x 0 = 0 just as 10 x 1024 = 0 so for all we know there is no other intelligent life anywhere.

Now it’s true that if we multiply by 0 the result is the same. And it is also true that we don’t know the value of the multiplier, since we don’t know how common life is. But if we multiply by any other possible number besides zero the result is vastly different. (Thus the power of the Drake equation.) If we multiply by 1, assuming that all planets have intelligent life then 10 x 1 yields a vastly different number of planets with intelligent life than 1024 x 1. But most importantly the difference is astonishing when we multiply 10 x .00000000001 and 1024 x .00000000001. (Assuming the probability of intelligent life arising is vanishingly small.) In the former case there is virtually impossible for the other 10 planets to support intelligent life while in the former case the universe would be teeming with an unimaginably large variety and quantity of intelligent life. That is why there is a paradox. On the one hand we have no evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence, on the other hand the number of possibilities for there to be life is so large that it seems almost unimaginable that there is not intelligent life elsewhere.

Of course my interlocutor could object and say “but you don’t know the probability of intelligent life is .00000000001%! That is true, but I know it’s not zero. After all, we exist. And if the probability is anything other than zero then intelligent life on other planets is practically certain. The vastness of the universe thus gives us a good reason to believe that there is intelligent life elsewhere. Not a totally convincing reason, since we have no empirical evidence for the proposition, but a good reason nonetheless. Remember the ancient Greeks had good reasons to believe there were atoms 2,000 years before we had empirical evidence of atoms, since the hypothesis provided a solution to the problem of how one thing changed into another.

So while I’m agnostic about whether there is intelligent life, I maintain with Fermi that the vastness of the universe with its countless number of stars and planets increases the chances that life exists elsewhere. And if I had to bet one way or the other, I would bet that there is intelligent life elsewhere. I may be wrong, but I think it is a good bet. Would any thinking person really bet against that? I think not.

July 5, 2014

July 4th and the Dangers of Patriotism

Yesterday was the 60th July 4 of my life. My wife and I heard a small band play patriotic music in the park and the band director made the usual speech. This a line from his speech almost verbatim: “America is the greatest country in the world and the greatest nation ever to have existed in history.”

Such a claim is easy to refute. The United States does not rank number 1 or even in the top 10 in the United Nations 2014 World Happiness Report. (A detailed report of quality of life.) And by multiple metrics–health care, education, economic equality, life expectancy, infant mortality, income mobility and more–it is nowhere near the top. It is also hard for the USA to compare favorably with many societies in history. For example, the use of the civil service examinations in ancient China helped produced nearly a thousand years of peace and prosperity–truly one of the greatest civilizations in history.

However the USA is number one in total number of persons and per capita incarceration, military spending (7 times more than any other nation), adult obesity, divorce rate, hours of TV watched, reported car theft, rapes, murders and total crime, both legal and illegal drug use, student loan debt, pornography created (90% of the world porn is created in the USA), and more. (We are #5 in executions behind China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq; but ahead of Pakistan and North Korea. So we need to work harder here to be #1.)

But perhaps the band director was not an O’Reilly, Limbaugh, or Hannity demagogue but a sincere believer. Perhaps he loves civilization in general and his in particular; perhaps he was expressing a warm feeling for his homeland; or perhaps he loves the ideals on which his country was founded. He might grant that the USA was not really number one objectively, but subjectively. For better or worse, he loved this place; it was his home.

To better understand the band leader’s feelings compare them with the sentiment of a Christian or Muslim who learns about Taoism or Buddhism. Such persons might conclude that these Eastern religions are superior to their own–say because they seem more consistent with modern science or have historically engaged in less persecution. Still such individuals might retain their current religious affiliation because it is comfortable and familiar. Maybe they just can’t see themselves as Buddhists. Perhaps the band leader felt something like this. Not that the USA was objectively better than the Scandinavian countries–which top the USA by a wide margin in most metrics–but that the USA was better for him. Ok, it is hard to argue with a feeling.

Still there is something troubling about the “USA number 1″ talk. First it is self-congratulatory. It covers up a real insecurity. If we are really #1 must we remind ourselves and others of it constantly? If you are a great person do you always have to tell everybody how great you are? Isn’t all the boasting indicative of the lack of humility?

Moreover, if we see our country in such a fine light we may lack the motivation to improve it. Who cares that 22% of all children in the USA grow up in families living below the federal poverty level, or that nearly 50% grow up in families that can’t meet basic expenses! Who cares that the USA has more people under correctional supervision than were in Stalin’s gulags! Who cares that the USA is the only developed nation in which millions of its citizen have no access to health insurance and thus lack basic health care? (These numbers are declining thanks the Affordable Care Act. Better still to have a national health-care system like all the other developed countries of the world–it is less costly and delivers better results. It is better both morally and economically.) Who cares about any of this since the USA is #1?

So when I’m asked “do you love your country?” the answer is mixed. I love my wife and she is part of the country. I love the national parks and they are a part of the country. But I don’t love mass incarceration, thousands dying for lack of health care or levels of economic inequality surpassing those of the gilded age. To love such things about your country is perverse. On balance then the USA is better than some but worse than a lot others, assuming your basic criteria is providing the conditions in which all citizens have the opportunity to flourish. (This was roughly Aristotle’s view of a good society.)

But most importantly this patriotic bravado is dangerous. If we are the greatest nation then imposing our culture on others naturally follows–patriotic fervor is a large part of the origin of imperialism and genocide. I have written elsewhere about how believing that you have a monopoly on the truth can be perilous, and the same can be said of cultures believing they are the best. Here is how the contemporary American philosopher Simon Critchley makes this point:

The play of tolerance opposes the principle of monstrous certainty that is endemic to fascism and, sadly, not just fascism but all the various faces of fundamentalism. When we think we have certainty, when we aspire to the knowledge of the gods, then Auschwitz can happen and can repeat itself. Arguably, it has repeated itself in the genocidal certainties of past decades. … We always have to acknowledge that we might be mistaken. When we forget that, then we forget ourselves and the worst can happen.

This moving video excerpt from Dr. Jacob Bronowski, a British mathematician and polymath poignantly drives home this point. In the old video Bronowski visits Auschwitz, where he reflects on the horrors that follow when people believe their culture and their nation and culture are the best. The video serves as a testimony to remind all of us to be more humble.

July 1, 2014

The Evolution, Complexity, and Cognition Group

I have just been accepted as an affiliate member of the prestigious Evolution, Complexity, and Cognition Group at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). I am excited to be associated with this group and their important research, and I look forward to the possibility of presenting a seminar in Belgium in the coming years. Here is a brief description of my research interests and how they align with ECCO’s.

I first became interested in systems theory, a fundamental research interest of ECCO, while doing research for my 1996 book Piaget’s Conception of Evolution: Beyond Darwin and Lamarck, and that interest recently resurfaced while writing the article on Piaget’s biology for The Cambridge Companion to Piaget (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy). Piaget’s theory of biological evolution involves feedback systems similar to those of Bertalanffy’s and Prigogine’s, two of the most important systems theorists. In fact, the motivation for Piaget’s work was nearly identical to the description of the “transdisciplinary perspective” noted on the ECCO website: “to unify science by uncovering the principles common to the holistic organization of all systems…” Moreover, the ECCO philosophy’s emphasis on “evolution and self-organization” is identical to Piaget’s approach. Piaget believed that regulatory self-organization was an invariant function in both the biological and epistemological realms and the key mover of evolution at various levels.

My most recent research involved writing two books on the meaning in life in a world revealed by modern science. This works studies the relevance of contemporary science and technology–especially cosmology, evolution, systems theory, artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnology, and genetic engineering–for the question of life’s meaning. My research led to the discovery of the work of ECCO researchers Clement Vidal and John Stewart, whose work on the meaning of life was summarized in my blog (here and here) and in my most recent book. Thus the connection with the ECCO group.

I agree that we need “a comprehensive philosophical system, a coherent vision of the whole. A worldview [that] gives meaning to our life.” And I also believe that presently such worldviews are “all too often found in fundamentalist ideologies, or in irrational beliefs and superstitions.” Thus “we need to develop a coherent, new worldview that is solidly rooted in the most advanced scientific concepts and observations.” And I have no doubt this meaning will be found, if it is to be firmly anchored, on the idea of a self-organizing cosmos in which order emerges from chaos.

Note – All quotes from the ECCO website.

June 26, 2014

The Fermi Paradox

Our massive sun cannot be seen in this image of the Milky Way, one of billions of galaxies.

THE UNIVERSE IS UNIMAGINABLY VAST

Our universe is vast beyond imagination. Really, you cannot imagine how vast it it. If you look into the night sky in perfect conditions you might be able to see about 2,500 stars, but that is only 0.000001 of the stars in the Milky Way. There are between 100 and 400 billion stars in our galaxy and about the same number of galaxies in the observable universe. Thus there are about 1023 total stars or 100000000000000000000000 stars in the observable universe. For every grain of sand on earth there are 10,000 stars out there! If you don’t think that is a lot go to the beach, play in the sand, and look around.

And these numbers are just stars. If our star, the Sun, is typical in having 8 planets then our universe alone contains something like 2 trillion stars! Now we don’t know what percentage of those stars is sunlike but if we go with a conservative estimate of 5% and the lower end for the number of stars 1022 then there are about 500 quintillion, or 500 billion billion sun-like stars!

Now if we go with the most recent conservative estimate of how many of those sun-like stars are orbited by earth-like planets, around 22%, that leaves us with 100 billion billion Earth-like planets! A hundred earth-like planets for every grain of sand on earth. Now if only 1% of those earth-like planets orbiting sun-like stars developed life and if only 1% of those planets developed intelligent life then there would be 10 quadrillion, or 10 million billion intelligent civilizations in the observable universe! In our galaxy alone there would be 100,000 intelligent civilizations.

All of which caused the physicist Enrico Fermi to ask, why haven’t we encountered beings from other worlds?

The fact is that SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) has never picked up a single radio wave or any other form of contact. If you don’t think this is surprising consider that there are older stars with far older Earth-like planets on which more advanced civilizations could have developed. They could be civilizations that have harnessed all the energy of their planet or the star or their entire galaxy if they were sufficiently advanced. If so they would have seemingly colonized the entire galaxy. Some scientists have hypothesized that civilizations could create self-replicating machinery that colonize the entire galaxy in around 4 million years.

Source: Scientific American: “Where Are They”

Source: Scientific American: “Where Are They”

And if only 1% of intelligent life survives long enough to become a potentially galaxy-colonizing civilization, there would still be 1,000 of those types of civilizations in our galaxy alone. So again, why haven’t we seen or heard for them? Where is everybody?This is the Fermi Paradox.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS FOR THE FERMI PARADOX

Here are a few of the explanations proposed to explain the paradox:

1) Higher civilizations are rare. Maybe something dooms them as they advance. Perhaps only a few of them have managed to surpass whatever it is that dooms civilizations and they have not spread out through the galaxy.

2) Higher civilizations don’t exist. We are the only civilization that has avoided destruction.

3) Higher civilizations don’t exist. We will soon destroy ourselves too.

4) Higher civilizations visited earth before we were here or before we had ways to record the visit.

5) Higher civilizations have colonized the galaxy but not our part of it.

6) Higher civilizations are not interested in colonization.

7) Higher civilizations no better than to broadcast their existence, since there are predator civilizations out there.

8) There is one higher predator civilization which has exterminated all other civilizations.

9) Higher civilizations are out there but we don’t know how to identify them.

10) Higher civilizations are observing us now but don’t want us to know. Perhaps they abide by the “Prime Directive” of Star Trek’s Federation.

11) Higher civilizations are all around us but we can’t perceive them.

12) We are wrong about reality; the universe is not vast in space and time.

I have no idea which if any of these hypotheses is true. What I do know is that our ignorance humbles me. The universe is not only bigger than we can imagine but probably stranger than we can imagine as well. All we have, as Xenophanes said long ago, “is a woven web of guesses.” And for those who cannot tolerate uncertainty and ambiguity there is always fanatical ideology. As for me I’ll accept former and live with integrity.

June 24, 2014

What is the Cosmos? Who are We?

What is the cosmos? – The cosmos is a vast incomprehensible mystery about which we can say one thing for sure–it doesn’t care about us. It can turn against us in multiple ways at any moment and eventually it will kill us. For almost all of its life we didn’t even exist, and for most of its future we probably won’t either. We are of the cosmos and part of it, but we are not central to its concerns, we did not have to be, we are extraneous.

Who are we? – Our existence was born “red in tooth and claw,” and any of a trillion slight changes and we wouldn’t be here. But we are here, as the product of random mutations and environmental selection. Our hodgepodge of traits include: aggression, territoriality, dominance hierarchies, sexual behaviors, and other traits of the primates and lower animals. We are not fallen angels, we are modified monkeys.

What does this mean? – Only we can raise ourselves up, and we have a lot of raising to do. An honest look at life provides a picture so bleak that we turn away. Addictions, violence, greed, materialism, fantasy, group loyalty, and religious, moral and political fanaticism shield us from reality and destroy the better selves we could be.

We are surrounded by an unimaginably cold, dark and inhospitable cosmos. Here on this pale blue dot beneath the thin blue line of our atmosphere, we exist on a friendly island in the universe’s vastness. Yet we willfully destroy our planet so that we can have bigger cars, houses and shiny things. In the meantime others live in squalor, and a thousand sophistries justify our selfishness. Meanwhile the planet becomes uninhabitable and unending war continues.

All the while the good people sign their petitions, raise their children, pay their taxes, follow the law, volunteer, and try to be better people. For the most part they remain quiet; no one listens to them. Meanwhile Dick Cheney and Rush Limbaugh pontificate for the masses. The worst of our species attracts the most attention.

Can we say anything positive about all this? I don’t know. The world looks bleak and I’m not going to become a Scientologist or join the Tea Party. We must have hope but the world tries to rip it away from you everyday. For today, Schopenhauer put the sentiment I feel best:

“If God made the world I could not be that God, for the misery of the world would break my heart.”

June 23, 2014

The Case for Soft Core Atheism

I would like to summarize and comment on the May 15, 2014 New York Times interview of philosopher Philip Kitcher by the philosopher Gary Gutting on the topic of “The Case for Soft Atheism” It is closely connected with the issues in my previous post, “Modern Cosmology Versus Creation by God.” Here is an abridged version of the conversation.

G – You “take religious doctrines to have become incredible.” Why do you say that?

K – “The most basic reason for doubt about any of these ideas is that … nobody is prepared to accept all of them.” They are often contradictory and can’t all be true. Moreover if you had been brought up in a different culture you would probably have different beliefs, so how can you say that your views are the correct ones?

G – Perhaps it’s not doctrines but religious experiences that are important, and many of these experiences are similar across cultures.

K – Experiences, even if they are similar, are not independent of doctrines. Moreover so-called religious experiences are easily confused with all sorts of psychological experiences that have psychological or biological causes.

G – So you reject all religious doctrines but “resist the claim that religion is noxious rubbish to be buried as deeply, as thoroughly and as quickly as possible.” Why ?

K – I advocate a soft atheism which recognizes that religious doctrines are not literally true but that some religious practices and concern for social justice are worthwhile.

G – So you think that atheists like Dawkins only refute unsophisticated religious claims?

K – Yes. Religions based on promoting humanistic values reject a literal interpretation of many of their doctrines are immune from much atheistic criticism. And by not considering the stories and metaphors of other religions literally either, you don’t have to choose between them, since they all may have some values in common.

G – So you will tolerate this refined religion?

K - Yes but eventually I would like to religion morphing into, and being replaced by, a kind of secular humanism. I don’t ignore religion, but I do want it to gradually disappear.

G – You don’t believe religious accounts of a deity but you don’t exactly say they are definitely false either. Why don’t you just say you’re an agnostic rather than an atheist?

K – Conflicting religious doctrines show that we can’t describe this supposed reality so we should “reject substantive religious doctrines, one and all, even the minimal ones …” I think theism is false, hence I call myself an “a-theist.”

G – But just because we can’t describe deities it doesn’t follow that they don’t exist. We can’t completely describe what a banana tastes like or what being in love is like but we don’t conclude that they don’t exist.

K – I think we know a lot about bananas and love. I reject theism rather because”I start from the idea that all sorts of human inquiries, including but not limited to the natural sciences, have given us a picture of the world, and that these inquiries don’t provide evidence for any transcendent aspect of the universe.” Of course our picture of reality is incomplete, but when people make fantastic claims about the existence and actions of ghostly beings without evidence, it isn’t dogmatic to reject such assertions.

G- What of religious experience?

K – There are adaquate scientific explanations them thus “referring such experiences to some special aspect of reality is gratuitous speculation.” These experiences testify to the religious ideas in a culture, not to any transcendent reality.

G -But there are respectable arguments for the existence of gods.

K – The arguments are all deeply problematic and at most are supplements to faith.

G – “I agree that no theistic arguments are compelling, but I don’t agree that they all are logically invalid or have obviously false premises.”

K – I believe that religion at its best should not defend dubious metaphysical doctrines but focuses on human problems. Let us then be inspired by the humanism in religion. “The atheism I favor is one in which literal talk about “God” or other supposed manifestations of the “transcendent” comes to be seen as a distraction from the important human problems — a form of language that quietly disappears.”

Commentary – Kitcher’s position is reminiscent of Dewey’s view that religion must disappear but the religious attitude is worthwhile, an idea I first encountered more than 40 years ago. I’ll let Dewey speak for himself while silently nodding my agreement.

If I have said anything about religions and religion that seems harsh, I have said those things because of a firm belief that the claim on the part of religions to possess a monopoly of ideals and of the supernatural means by which alone, it is alleged, they can be furthered, stands in the way of the realization of distinctively religious values inherent in natural experience. For that reason, if for no other, I should be sorry if any were misled by the frequency with which I have employed the adjective “religious” to conceive of what I have said as a disguised apology for what have passed as religions. The opposition between religious values as I conceive them and religions is not to be abridged. Just because the release of these values is so important, their identification with the creeds and cults of religions must be dissolved.

As I have stated many times in this blog the replacement of religious superstition by scientific rationalism will benefit us and our descendants. In the end such considerations lead to the promulgation of secular humanism and eventually to transhumanism. Looking around the world today, a better future can’t get here fast enough.

June 21, 2014

Modern Cosmology Versus Creation by Gods

I would like to briefly summarize and then comment on the June 15, 2014 New York Times interview of philosopher Tim Maudlin by the philosopher Gary Gutting entitled “Modern Cosmology Versus God’s Creation.” Here is an abridged version of that conversation.

G - “Could you begin by noting aspects of recent scientific cosmology that are particularly relevant to theological questions?”

M – It depends on the theological account. Modern cosmology refutes the Biblical account of an earth at the center of creation–the universe is vast and we are not at its center.

G – Just because the universe is big and we aren’t at the center doesn’t mean we can’t have a spiritual relationship with our god. Besides, there may be other purposes for the universe or other creatures with relationships with our god.

M – Humans may or may not have an important role in the universe, or perhaps the universe doesn’t care about any beings. But accounts that make us the main purpose of the creation seem contrary to have the evidence.

G – Biblical literalism is inconsistent with cosmology but other versions of theism–like the belief that an intelligent being created the cosmos–are not refuted by modern cosmology.

M – Traditional theism doesn’t just say some being created the universe, but that it was created with us in mind. The evidence of the huge structure of the cosmos, with most of it irrelevant to life, our location in that universe and the eons of time necessary for evolution belie the claim that it was created for us.

G- Perhaps, but we don’t know what a creator wants. Maybe the creator made a huge universe for us to study. Also what do you think about fine tuning–the idea that the constants, parameters and laws of nature are seemingly perfect for life?

M – We don’t know what these constants are, or if they are even constant, so we can’t say much about them from a scientific point of view. But if a deity wants us to know of its existence there would be easier ways to let us know.

G – That assumes we know how deities behave. But I’ll admit that we might explain the constants scientifically.

M- Yes. For example if there are an infinite number of universes then life would probably evolve somewhere.

G – So we don’t know if fine-tuning for human life supports theism?

M – ” … note how “humans” got put into that question! If there were any argument like this to be made, it would go through equally well for cockroaches. They, too, can only exist in certain physical conditions.” Imagine a deity who created the universe with us as an unintended byproduct of nature’s constants. This is as plausible a hypothesis for the constants of nature as the Biblical hypothesis that the cosmos was made for us.

G – What about the idea we need a creator to explain the existence of the universe? And what about the view of some cosmologists, like Lawrence Krauss, that a quantum fluctuation could have produced something from nothing?

M – People want more than a creator as an explanation, they want to be significant in the creation. Also a nonmaterial cause must either be explained by something else–in which case its not the ultimate cause–or it explains itself–in which case we might as well say the cosmos is its own cause as a god is. And if the universe is infinite then it didn’t have a cause at all. As for Krauss, he thinks the quantum vacuum state is where causation ends but I don’t think we can answer these questions definitively.

G – So scientific cosmology doesn’t support theism, and it refutes the claim that we are the primary purpose of god’s creation. Still would you grant the minimal claim “that the universe was created by an intelligent being” as at least reasonable, or does science support atheism or agnosticism?

M – “Atheism is the default position in any scientific inquiry, just as a-quarkism or a-neutrinoism was. That is, any entity has to earn its admission into a scientific account either via direct evidence for its existence or because it plays some fundamental explanatory role.” The main problem with a minimalist account is “that in trying to be as vague as possible about the nature and motivation of the deity, the hypothesis loses any explanatory force, and so cannot be admitted on scientific grounds. Of course, as the example of quarks and neutrinos shows, scientific accounts change in response to new data and new theory. The default position can be overcome.”

Commentary – The more specifically we define the gods, the less likely they are to be real on mere probabilistic grounds. The more vague we are about them, the less we say when we talk about them. If good scientific evidence for the gods appears, then we should give belief in them our provisional assent. Until such time we should not believe in them. Let me conclude by quoting my previous post.

Still people will find their gods hiding in the gaps of quantum or cosmological theories, or in dark matter or energy. If you are determined to believe something it is hard to change your mind. But defenders of the gods fight a rearguard action–scientific knowledge is relentless–and these hidden gods are nothing like the traditional ones. Those gods are dead.

And as science closes the gaps in our knowledge the gods will recede further and further into the recesses of infinite space and time until they vanish altogether, slowly blown away, not by cosmic winds, but by ever encroaching thought.