John G. Messerly's Blog, page 139

August 8, 2014

The American Political Spectrum: Circa 2014

US President Richard Nixon resigned the Presidency 40 years ago today.

In my previous post I continually referred to “so-called” liberals and conservatives. I did this because the American political spectrum has moved so far to the right in the last 40 years. What we call a liberal today is, for the most part, yesterday’s centrist or conservative; and what we call a conservative today is well to the political right, well outside the mainstream, of the politics of forty years ago.

Consider former US Republican president Richard Nixon who resigned the Presidency to avoid impeachment forty years ago today. As the political columnist Mark Shield says, “Nixon was the last liberal president.” Even conservative commentator David Gergen agrees that Nixon couldn’t be elected as a Republican today.1 Nixon contemplated a total ban on handguns, supported the earned income tax credit, gave the vote to 18 year olds, set up the EPA, opened diplomatic relationships with China, was not a staunch opponent of abortion, and lobbied for a universal health-care system. This was the Republican president of just 40 years ago. I think he would be too liberal to be nominated by today’s democratic party.

By contrast, today’s Democrats don’t generally take the lead in supporting organized labor, or the New Deal or Great Society programs. (A possible exception would be Social Security, but even here so-called liberals willingly discuss gutting the system.) Today’s so-called liberal presidents dismantle welfare and openly solicit the aid and advice of Wall Street. And they wouldn’t dare be as bold as Nixon on gun control, the environment, or health care. (This is Nixon were talking about.) The strong rightward lurch of the US Supreme Court has been well-documented by scholars of the court as well.2 How do we explain these changes? While it would take a book-length discussion to do justice to this topic, we can say a few things.

The modern conservative movement (movement conservatism) had its beginnings in the 1950s with the publication of the National Review, with its intellectual might largely supplied by William F. Buckley. Some of Buckley’s ideas were later adopted by the John Birch Society but Buckley, to his credit, regarded them as a fringe group.3,4 (Not surprisingly Fred Koch, father of the radical right-wing supporters Charles and David Koch, was one of its founding members.) From these beginnings on the far right, modern conservatism has become ever more radicalized to the point that its proponents now willingly threaten the world economy to get their way over small policy details. As for the left of American politics–roughly the mainstream of politics in Western Europe and Scandinavia–classical liberals like Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson, or Ted Kennedy are nearly extinct (with the exception of someone like Bernie Sanders of Vermont), as are moderate republicans like Dwight Eisenhower or Richard Nixon. The rightward movement of American politics since the mid-1970s is self-evident to any impartial observer.

Interestingly this time period from the mid-1970s to the present corresponds almost precisely with the flattening of wages in the US, the growth of income inequality, the destruction of labor unions, mass incarceration, and numerous other measures of social and economic dysfunction. Whether correlation equals causation is another matter, but the correlation is unmistakable. But my main point is that liberal and conservative labels are not particularly useful in describing American politics today. At the moment in America there is a centrist party that exists with Wall Street backing, and a far, far right reactionary party with its roots in the Old American South and organizations like the Birch society.

How will this all turn out? I have no idea. The radical right has an overwhelming advantage in that Americans get their news from a few media conglomerates which promote the current status quo. These majority owners of these outlets are disproportionately white, wealthy and right-wing. Even the so-called liberal media outlets like the New York Times are conservative by world standards. The NY Times supports most American military ventures, rarely discuss labor issues, and employ a number of conservative columnists. They are certainly not radical, and they would certainly never advocate for a populist revolution or anything close. In short, the right has a huge advantage in messaging.

The left has the advantage of their positions are overwhelming popular–a more equitable distribution of wealth, environmental regulations, universal access to health care, access to child-care, less influence of the super wealthy in the political process, a stronger social safety net, etc. They also have an overwhelming advantage in population numbers and demographic trends in the US. These demographic trends should make the Democratic party in the US nearly invincible in national elections, although this currently has little effect on Congressional representation. Moreover, Republicans in the US may succeed with their two basic strategies to combat the overwhelming numbers of Americans who want populist reforms: 1) suppress voting through ID laws; and 2) increase the input of the ultra-rich in campaigns. In this way the can increase the influence of the rich and decrease the influence of everyone else. If they succeed, then populism may lose.

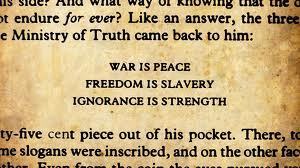

In that case the US will become a country of, by, and for the wealthiest classes. Again I don’t know how this will turn out. It might be the masses will wise up to messengers who work against their economic interest. They may come to realize that gay, atheistic, flag-burning, gun-hating immigrants and their progressive brethren are not their enemy but rather useful ploys the oligarchs use to exploit us all. On the other hand the techniques of political manipulation have become increasingly powerful. Perhaps the oligarchs will use it to further control the rest of us, or perhaps they will dispense with us altogether as technology eliminates the need for workers. I hope this doesn’t happen but if it does, a nightmarish Orwellian future awaits us.

______________________________________________________________________

1. http://thecolbertreport.cc.com/videos...

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideologi...

3. Regnery, Alfred S. (2008-02-12). Upstream: The Ascendance of American Conservatism. Simon and Schuster. pp. 79–. ISBN 978141652288

4. Chapman, Roger (2010). Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices. M.E. Sharpe. p. 58.ISBN 9780765617613.

August 7, 2014

GMOs: Are They the Liberal Equivalent of Climate Change Denial?

(For the record, I eat organic fruits and vegetables when available and I am practically a vegetarian–although I occasionally eat fish. I also accept the argument that Monsanto and similar companies are interested in profit alone. However this doesn’t mean that everything they produce is necessarily bad for you. It just means that they are not necessarily good for you.)

GM Crops

I was introduced to the issue of GMOs (genetically modified organisms) while teaching a few years ago. Looking dispassionately at the pros and cons it became apparent that there was a broad scientific consensus that GM crops pose no greater risk than conventional ones. 1,2,3 It was also obvious that the opponents of GM crops were generally modern day Luddites who opposed technology. The pro side of the argument won handily as best as I could ascertain. (I’ll leave aside the issue of GM animals, and the issue of the means by which companies like Monsanto get (force) farmers to use their products.)

Some students were surprised that I advocated strongly for vegetarianism–for environmental, moral, and health reasons–and for organic food–for health reasons–but that I didn’t mind my food “engineered genetically.” I responded that I would eat whatever was healthier, whether that was organic plants or a magic nutritional pill. (Ideally this pill would also prevent death and disease too! Yes I’m serious.)

GMOs, Climate Denial, and Politics

There is a perception among some that opposition to GMOs among so-called liberals is higher than it is among so-called conservatives. There is also the perception that such opposition from liberals is ideologically driven, similar to how climate change denial is among conservatives. I argue that both claims are mistaken.

The perception that opposition to GMOs is higher among self-described liberals rather than self-described conservatives one can be refuted by the data.4 The perception probably exists because of the publicity given to certain events. For instance, efforts to ban GM crops in Hawaii were led by so-called liberals who disregard the scientific evidence for GMO’s safety.5

But even if so-called liberals did oppose GM crops more than so-called conservatives, the latter are generally more anti-science, as has been carefully documented in numerous well-researched books.6,7,8 Opposition to the scientific consensus on climate change and reverence for the Bible are virtual litmus tests to be a Republican in America today. Or to take another example, only 32% of Republicans believe in evolution, while 66% of liberals do. (Although to be fair, there is scientific illiteracy among all Americans as even this latter percentage reveals. In fact only about 1/2 of all Americans know that the earth revolves around the sun and that it takes a year to do so!)

There is also another difference regarding the extent to which ideology drives the debate. So-called conservatives seem to wear climate change or evolution denial as a badge of honor. Even Republicans who know the truth of climate change–like Mitt Romney or John McCain have to fall in line. No doubt ideology drives so-called liberals too, but hardly to the same extent. Liberals may be mistaken about the harmfulness of GMOs, but they don’t generally wear this as a badge of honor. The astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, something of a liberal icon, has recently stated that GMOs are not harmful.9 And in the hearings over banning GM foods in Hawaii were heard this: “These are my people, they’re lefties, I’m with them on almost everything,” said Michael Shintaku, a plant pathologist at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, who testified several times against the bill banning GM foods.

Hopefully some educated conservatives will speak this way about climate change, evolution, opposition to vaccines, and similar scientific illiteracy.

The Most Important Issue

The most important issue in all this, as I have stated many times in this blog and in my writing and teaching for almost 30 years, is that truth matters. We should all have a truth fetish. We should follow reason and science wherever it leads. For we ignore scientific truth at our peril. For in the end scientific truth does not depend on us, it depends on what is most likely to be true.

_________________________________________________________________________

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Board of Directors (2012). “Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers“

A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010) (PDF). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Biotechnologies, Agriculture, Food. European Union. 2010.doi:10.2777/97784. ISBN 978-92-79-16344-9. “”The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research, and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies.” (p. 16)”

Ronald, Pamela (2011). “Plant Genetics, Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security”. Genetics 188 (1): 11-20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553.PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnx...

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles...-

The Republican War on Science

The Republican War on Science

Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the …

Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the …

The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny …

The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny …http://www.vox.com/2014/8/1/5954701/n...

GMOs: Are They the Liberal Equivalent of Climate Change Denial? No

(For the record, I eat organic fruits and vegetables when available and I am practically a vegetarian–although I occasionally eat fish. I also accept the argument that Monsanto and similar companies are interested in profit alone. However this doesn’t mean that everything they produce is necessarily bad for you. It just means that they are not necessarily good for you.)

GM Crops

I was introduced to the issue of GMOs (genetically modified organisms) while teaching a few years ago. Looking dispassionately at the pros and cons it became apparent that there was a broad scientific consensus that GM crops pose no greater risk than conventional ones. 1,2,3 It was also obvious that the opponents of GM crops were generally modern day Luddites who opposed technology. The pro side of the argument won handily as best as I could ascertain. (I’ll leave aside the issue of GM animals, and the issue of the means by which companies like Monsanto get (force) farmers to use their products.)

Some students were surprised that I advocated strongly for vegetarianism–for environmental, moral, and health reasons–and for organic food–for health reasons–but that I didn’t mind my food “engineered genetically.” I responded that I would eat whatever was healthier, whether that was organic plants or a magic nutritional pill. (Ideally this pill would also prevent death and disease too! Yes I’m serious.)

GMOs, Climate Denial, and Politics

There is a perception among some that opposition to GMOs among so-called liberals is higher than it is among so-called conservatives. There is also the perception that such opposition from liberals is ideologically driven, similar to how climate change denial is among conservatives. I argue that both claims are mistaken.

The perception that opposition to GMOs is higher among self-described liberals rather than self-described conservatives one can be refuted by the data.4 The perception probably exists because of the publicity given to certain events. For instance, efforts to ban GM crops in Hawaii were led by so-called liberals who disregard the scientific evidence for GMO’s safety.5

But even if so-called liberals did oppose GM crops more than so-called conservatives, the latter are generally more anti-science, as has been carefully documented in numerous well-researched books.6,7,8 Opposition to the scientific consensus on climate change and reverence for the Bible are virtual litmus tests to be a Republican in America today. Or to take another example, only 32% of Republicans believe in evolution, while 66% of liberals do. (Although to be fair, there is scientific illiteracy among all Americans as even this latter percentage reveals. In fact only about 1/2 of all Americans know that the earth revolves around the sun and that it takes a year to do so!)

There is also another difference regarding the extent to which ideology drives the debate. So-called conservatives seem to wear climate change or evolution denial as a badge of honor. Even Republicans who know the truth of climate change–like Mitt Romney or John McCain have to fall in line. No doubt ideology drives so-called liberals too, but hardly to the same extent. Liberals may be mistaken about the harmfulness of GMOs, but they don’t generally wear this as a badge of honor. The astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, something of a liberal icon, has recently stated that GMOs are not harmful.9 And in the hearings over banning GM foods in Hawaii were heard this: “These are my people, they’re lefties, I’m with them on almost everything,” said Michael Shintaku, a plant pathologist at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, who testified several times against the bill banning GM foods.

Hopefully some educated conservatives will speak this way about climate change, evolution, opposition to vaccines, and similar scientific illiteracy.

The Most Important Issue

The most important issue in all this, as I have stated many times in this blog and in my writing and teaching for almost 30 years, is that truth matters. We should all have a truth fetish. We should follow reason and science wherever it leads. For we ignore scientific truth at our peril. For in the end scientific truth does not depend on us, it depends on what is most likely to be true.

_________________________________________________________________________

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Board of Directors (2012). “Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers“

A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010) (PDF). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Biotechnologies, Agriculture, Food. European Union. 2010.doi:10.2777/97784. ISBN 978-92-79-16344-9. “”The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research, and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies.” (p. 16)”

Ronald, Pamela (2011). “Plant Genetics, Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security”. Genetics 188 (1): 11-20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553.PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnx...

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles...-

The Republican War on Science

The Republican War on Science

Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the …

Idiot America: How Stupidity Became a Virtue in the Land of the …

The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny …

The Republican Brain: The Science of Why They Deny …http://www.vox.com/2014/8/1/5954701/n...

August 3, 2014

The Case Against Hope

Read an interesting column in the Guardian the other day which argued against hope in certain circumstances. The author, Oliver Burkeman, argued that what is often called hope is really deception–hoping for things which are virtually impossible. For example hoping that one wins the lottery or that the victims of an accident have survived when their deaths are near certainties. In contrast letting go of hope often sets us free. To support his claim he refers to “recent research … suggesting that hope makes people feel worse.” For instance: the unemployed who hope to find work are less happy than those who accept they won’t work again; those in the state of hoping for a miraculous cure for a terminal disease are less happy than those who accept the hopelessness of the situation; and many become more active in working for change when they stop hoping for others to do it. Perhaps there is something about giving up hope and accepting reality that is comforting.

Reflections – While I stress the importance of hope in my own thinking–we should generally hope for the best, hope that life has meaning, hope that justice prevails, etc.–the author is clearly on to something. False hopes are futile, leading to inevitable disappointment. Hope against the evidence is false hope, divorced from reality. If I hope to win the lottery, become a famous author or the world’s greatest tennis player my expectations are bound to be dashed. Much better to hope to enjoy my work and make enough money to support my family, and to enjoy writing and tennis and do them as well as I can. It is important to want or wish for good outcomes, but not when such wanting or wishing denies reality.

When confronted by the reality of the concentrations camps in World War II, Victor Frankly did not hope to dig his way out of his prison. That was not possible and such hopes would soon have been dashed, leading to inevitable depression at the hopelessness of his situation. Instead he controlled his own mind and (probably) vaguely hoped for something realistic–like that the war would someday end and he might be freed. That is the difference between false and realistic hope. The former is delusional, the latter worthwhile. Sometimes only fools keep believing; sometimes you should stop believing.

August 2, 2014

Knowledge and Power: Our Retreat from the Enlightenment

Francis Bacon Thomas Hobbes

New York Times columnist and Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman recently wrote an interesting piece, “Knowledge Isn’t Power.” This contrasts with the received view that knowledge is power. Here is the opening paragraph of the relevant Wikipedia’s entry:

The phrase “scientia potentia est” (or “scientia est potentia“ or also “scientia potestas est”) is a Latin aphorism often claimed to mean organized “knowledge is power.”It is commonly attributed to Sir Francis Bacon, although there is no known occurrence of this precise phrase in Bacon’s English or Latin writings. However, the expression “ipsa scientia potestas est” (‘knowledge itself is power’) occurs in Bacon’s Meditationes Sacrae (1597). The exact phrase “scientia potentia est” was written for the first time in the 1651 work Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes, who was secretary to Bacon as a young man.1

For the philosophically uninitiated Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) “was an English philosopher … [and a] philosophical advocate and practitioner of the scientific method ... Bacon has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the Baconian method, or simply the scientific method.”2 Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) “was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy. His 1651 book Leviathan established social contract theory, the foundation of most later Western political philosophy.”3

Not surprisingly the idea that knowledge is power originated with an influential thinker who sparked the Enlightenment, Francis Bacon, and one of the most important figures of the Enlightenment, Thomas Hobbes. Interpretations of the phrase include the idea that knowledge increases one’s ability or potential, or improves one’s influence or reputation. In the prescriptive sense the idea is that knowledge should be powerful. It should inform and guide our public policies and decisions, and that by doing so (scientific) knowledge has power.

Krugman’s worries that scientific knowledge is losing its power to influence public policy. Instead, we have the appearance of knowledge holding sway. Many are largely influenced by demagogues or the ignorant rather than the educated. For example, there is a virtual consensus on a wide range of issues among leading economists “representing a wide spectrum of schools and political leanings, on questions that range from the economics of college athletes to the effectiveness of trade sanctions [to] whether … the Obama “stimulus” — reduced unemployment … [to] whether the stimulus was worth it …” Nonetheless policy makers and the public are often unaware of or ignore expert advice. This is not to say that the professional consensus is always right, but it does raise the question: “Are we as societies even capable of taking good policy advice?”

Reflections – Obviously if the answer is no to the above question, then knowledge has lost much of its power. And it is not only in economics but in biology, climate science, and other disciplines that policy makers ignore scientific consensus. This makes you wonder if our species can avoid disaster. Because ultimately the truth about economics, biology and climate science trumps ideology–evolution is still true, vaccines still prevent disease, and the climate is still changing. If our decisions are not informed by our knowledge, then they will be informed by our ignorance. We will return to the pre-Enlightenment world ruled by superstition and emotion, rather than reason and evidence. Let us hope that we act in accordance with the latter. After all, our survival depends on it. And if that doesn’t matter nothing else does.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientia_potentia_est#Interpretation

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Francis_Bacon

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobbes

August 1, 2014

The World is Full of Damaged Psyches

The world is full of damaged psyches, as adults who learns from experience soon discover. Still, this obvious truth is not apparent to children or to unreflective adults. The unreflective are satisfied with platitudes like “she seems nice” or “he’s so sweet” or “I’m a good person.” The inexperienced peer no deeper into the the psyche. But the reality behind the mask that humans wear often differs from the appearance. The seemingly nice and ok people are often neither nice or ok–and you might not a good person either.

It goes without saying that understanding the psyches around us is important. Individuals and groups are led astray when they misread them. Woman think they’ve found the perfect man, and six months later that have bruises. Nations trust their leaders, and later die in their unjust wars. Americans wonder about the appeal of Hitler or Stalin, psychopaths full or rage and patriotic fervor, but they fawn over their own psychopathic leaders and provocateurs. We are drawn to those who make us feel good about ourselves by directing animus toward others. So many political pundits and politicians are vile, horrific human beings filled with hate and vitriol, but people listen to them intently. Without a careful reading of the psyche, the demagogues hold sway.

And this says as much about most of us as it does about them. We too are often filled with hate, anger, treachery, irrationality, homophobia, xenophobia and sadism. As Shakespeare put it: “The fault … is not in our stars, but in ourselves …” We suffer in the presence of damaged psyches that spew their psychic waste, and we suffer enduring our own psyches too. So what can we do about this?

As for recognizing and eradicating our own demons, we might begin, as was suggested in a recent column, by quieting our minds, re-assessing who we are, and trying to become whole, integrated human beings. There is obviously more to explaining how to do this than this column permits. It may involve professional counseling, meditation, exercise and more. But I do think that people should be continually in the process of becoming, of changing, of transforming. This pursuit should last a lifetime or, if the reincarnationists are right, multiple lifetimes. (Yes, a literal interpretation of reincarnation is silly. But in the sense that people die and others are reborn with different genetic combinations is a kind of reincarnation.) We must begin by changing ourselves.

As for changing others, that is unlikely. Instead, we should avoid those who spew their toxic, psychic waste. If you can escape their presence, do so expeditiously. They will damage you. If you must interact with them, minimize contact. But respond to such interaction not with anger but with sympathy, for others had no control over the external situations that in large part created them. All you can control, as the Stoics taught long ago, is your own mind. Try not to be disturbed, but avoid masochistic tendencies too. You have no obligation to endure the psychologically unhealthy, escape them if you can.

As for recognizing severely damaged psyches in others, be patient. Don’t conclude too quickly that someone is “nice.” Aristotle said that everyone slowly reveals their character … and they do. No one remains opaque for long. People slowly become translucent and then transparent. Just wait. I didn’t know my wife well after I’d known her for a few months, and she didn’t know me. But now, after 34 years of living together, I sleep soundly next to her as she does with me. We don’t fear the other will kill us in our sleep.

How then should we live in a world of healthy and unhealthy psyches? Through the experience of living we can slowly learn to discriminate between healthy and unhealthy psyches. We can learn to be astute, savvy, judicious, sagacious, and discerning. We can learn to be wise, to discriminate between those who care for us, however flawed they might be, from those who don’t care for us, or from those who would hurt us. We learn that everyone, even those relatively healthy psyches, will sometimes hurt us. But this we should endure, if on balance they care for us. For solitude and loneliness damage the psyche too. Avoid then those who intend to hurt you, but love those that sometimes hurt your inadvertently, if they have shown they care for you.

Essentially we learn that a large part of living is psychic intercourse–that is where our minds primarily reside–that is largely what it is to be conscious. In a world of psychic intercourse, interact with beauty and avoid ugliness as much as possible, while continually trying to beautify yourself.

July 30, 2014

Beyond Energy, Matter, Time and Space?

George Johnson is a prolific science writer–the author of nine books and hundreds of articles. (He has written 14 articles for the New York Times in 2014 alone.) He is also, by all accounts, a fine man. Last week in the New York Times he wrote “Beyond Energy, Matter, Time and Space.” Here is a brief summary of that piece.

Human may have been demoted from their central place in the heavens by modern science, writes Johnson, but we still believe that we will eventually figure out the how the universe works. It is generally believed we will do this by utilizing four basic concepts: matter and energy interacting in space and time. But there are some skeptics who think we might need a few more concepts, notes Johnson.

The first is the philosopher Thomas Nagel. He thinks there is more to the universe than physical forces, and that evolutionary laws need to be expanded to explain sentient life. Needless to say Nagel’s views have caused consternation. The psychologist Steven Pinker, denounced Nagel’s latest book as “the shoddy reasoning of a once-great thinker.” Nagel, for his part, is an atheist who is not promoting non-scientific ideas like intelligent design. Instead he argues that science must continue to expand to find more complete answers. Nagel writes: “Humans are addicted to the hope for a final reckoning … but intellectual humility requires that we resist the temptation to assume that the tools of the kind we now have are in principle sufficient to understand the universe as a whole.” (Any thoughtful scientist would agree.)

The discovery or invention of a mathematics so in tune with reality also amazes Nagel. (Many evolutionary epistemologists are not surprised that brains, which evolve from nature, are thus in tune with nature.) Even neuroscientists cannot yet explain how mind emerges from the electronic circuitry of the brain. (That “they can’t explain that” posits some as yet unknown explanation. It is one thing to say this explanation is supernatural and by definition such explanations are outside the purview of science. It is another to say that further explanation is needed, and no scientist would disagree with that.)

To fully explain mind, Nagel argues, requires another scientific revolution. Such a revolution posits mind as fundamental and a universe primed “to generate beings capable of comprehending it.” This would require directional, possibly even purposeful evolution, and would expand on the model random mutations and environmental selection. “Above all,” Nagel writes, “I would like to extend the boundaries of what is not regarded as unthinkable, in light of how little we really understand about the world.” (Again few scientists would disagree. Thus Nagel’s views are not as revolutionary as they appear.)

In addition, notes Johnson, the biologist Stuart Kauffman also suggests that Darwinian theory must be expanded to explain the emergence of intelligent creatures like ourselves. (There is nothing surprising about this. My article on “Piaget’s Biology” in The Cambridge Companion to Piaget (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy) notes multiple biologists who argue similarly.) And David Chalmers, an important philosopher of mind, has seriously considered panpsychism–the idea that rudimentary consciousness pervades everything in the universe. (However Chalmers does not say that panpsychism and the physicalism underlying contemporary biology conflict, although he does say, in this interview, that panpsychism “is a radical form of physicalism precisely because it introduces mental properties as fundamental.” So Chalmer’s views are not as revolutionary as they appear. It seems to me that panpsychism might even be expected given the evolution of higher intelligences from lower one. It also seems, on briefest reflection, that this does not mean mind more fundamental than matter, but rather that it is an emergent property in evolution. My basic point is that the reference to panpsychism doesn’t clearly challenge scientific orthodoxy.)

notes multiple biologists who argue similarly.) And David Chalmers, an important philosopher of mind, has seriously considered panpsychism–the idea that rudimentary consciousness pervades everything in the universe. (However Chalmers does not say that panpsychism and the physicalism underlying contemporary biology conflict, although he does say, in this interview, that panpsychism “is a radical form of physicalism precisely because it introduces mental properties as fundamental.” So Chalmer’s views are not as revolutionary as they appear. It seems to me that panpsychism might even be expected given the evolution of higher intelligences from lower one. It also seems, on briefest reflection, that this does not mean mind more fundamental than matter, but rather that it is an emergent property in evolution. My basic point is that the reference to panpsychism doesn’t clearly challenge scientific orthodoxy.)

Johnson also notes that the renowned physicist Max Tegmark argues that mathematics is an irreducible part of nature–perhaps the most fundamental part. Johnson marvels at mathematics’ effectiveness in describing reality. (Piaget wrote extensively about how children’s reflective abstractions largely explain how the mind evolves, as well as the correspondence of mathematics and reality. And there are Platonic, evolutionary and other explanations of this correspondence.) Tegmark argues the universe is a mathematical structure from which matter, energy, space and time emerge. Other mathematicians note that most mathematics doesn’t describe reality at all. But for Johnson, Tegmark provides another example of a challenge to scientific orthodoxy.

Johnson conclusion from all this is mixed. On the one hand we’ve come a long way in understanding our universe in the 5,000 years or so of civilization. On the other hand, from the vantage point of 5,000 years hence, our science today will be primitive. So Johnson is not sure of the extent to which challenges to the orthodoxy are substantive.

My conclusion is that Johnson is correct about the former claim–we have come a long way since the dawn of civilization, but I’m not sure about his latter claim–that today’s science will be primitive in retrospect. In some ways this is true, but in others it may not be. There is a good chance that evolutionary, quantum, relativity, gravitational and atomic theories will survive almost intact. Why? Because while revolutionary disruptions occasionally happen in science, as Kuhn suggested, more often change is slow. Change is mostly gradual, evolutionary change, not radical, revolutionary change. Newton’s theory of gravity is not wrong–it works fine at speeds much slower than light–although Einstein’s theory of gravity is more complete. The ancient atomists were correct that atoms are small indeed even though they didn’t have a modern atomic theory. And Euclidean geometry is not invalid because of non-Euclidean geometry–parallel lines still don’t meet in Euclidean space! In the far future we may find out we knew a lot more than we thought we knew.

As for new ideas that challenge scientific orthodoxy I think Carl Sagan said it best: “It pays to keep an open mind, but not so open your brains fall out.”

July 29, 2014

The Art of Loving

I previously written a number of columns on love but I have not mentioned a small book I read in my early twenties–and the first book I ever gave to my wife–Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving. It begins thus:

I previously written a number of columns on love but I have not mentioned a small book I read in my early twenties–and the first book I ever gave to my wife–Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving. It begins thus:

Is love an art? Then it requires knowledge and effort. Or is love a pleasant sensation, which to experience is a matter of chance, something one “falls into” if one is lucky? This little book is based on the former premise, while undoubtedly the majority of people today believe it is the latter.“2

Fromm thought that many misunderstand love for a variety of reasons. First, they see the problem of love as one of being loved rather than one of loving. They try to be richer, more popular, or more attractive instead of learning to love. Second, they think of love in terms of finding an object to love, rather than of a faculty to cultivate. They think it is easy to love, but hard to find someone to love, when in fact the opposite is true. (This relates to our earlier discussion about the commodification of love.) Finally, people don’t discriminate between “falling” in love and what Fromm calls “standing” in love. If two previously isolated people suddenly discover each other it is exhilarating. But such feelings don’t last. Real love involves standing in love; it is an art we learn after years of arduous toil, just as we would learn any other art or skill. Real love is not something we fall into, it is something we learn to do.

In the end, though loving is difficult to learn and practice, it is most worthwhile, and more important than money, fame or power. For the mystery of existence reveals itself, if it ever does, through our relationships with nature, productive work and, most of all, through our relationships with other people. Thus to experience the depths of life, we should cultivate the art of loving in its many varieties.

July 28, 2014

On Thinking

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

~ Blaise Pascal

I recently read a short piece in the Guardian titled, “This column will change your life: just sit down and think.” It began with the above quote and noted a recent scientific study that showed how people detest spending even a few minutes alone in a room just thinking–almost half prefer giving themselves electric shocks during that time! The study also revealed that even with sufficient leisure time, almost no one spends it just thinking.

A possible explanation comes from the psychologist Steve Taylor’s recent book, Back To Sanity: Healing the Madness of Our Minds . Taylor argues that the “urge to immerse our attention in external things is so instinctive that we’re scarcely aware of it.” The cause of this phenomenon is the state of psychological discord that Taylor calls “humania,”(human madness) which is a product of our ego-separateness. (It also is the cause of the major problems facing humanity like warfare, oppression, and environmental destruction.) We mistakenly believe that we are isolated individuals encased inside our heads. Thus we fear that if we dwell on what’s inside, we will experience loneliness. In response, we distract ourselves with constant activity.

. Taylor argues that the “urge to immerse our attention in external things is so instinctive that we’re scarcely aware of it.” The cause of this phenomenon is the state of psychological discord that Taylor calls “humania,”(human madness) which is a product of our ego-separateness. (It also is the cause of the major problems facing humanity like warfare, oppression, and environmental destruction.) We mistakenly believe that we are isolated individuals encased inside our heads. Thus we fear that if we dwell on what’s inside, we will experience loneliness. In response, we distract ourselves with constant activity.

Taylor argues that this psychic discord manifests itself primarily as continuous “thought chatter” which makes us feel incomplete. We experience not serenity but the “madness of constant wanting,” of material possessions, happiness, power, fame, money, sex or whatever else we think will make us complete. While some are more affected by humania than others, Taylor believes that most modern Westerners suffer from this psychic discord caused by ego-separateness while, surprisingly, indigenous people do not.

Taylor’s prescription is to break through the “surface of our being,” the part “filled with disturbance and negativity,” to find that “deep reservoir of stillness and well-being” which is at our core. This does not entail returning to the lifestyle of indigenous people and foregoing modern conveniences, but rather learning how to be more integrated human beings. Yet we cannot find inner peace just by reading a book. We must work at our psychological development, toward attaining “a state of permanent harmony of being.”

Reflections – Inner peace is the best psychic state. If we do not experience it, we have almost nothing; if we experience it, we have almost everything. And we can find it by sitting quietly in a room alone. But reading about this is not enough. We must work at it. For as Spinoza said, “All noble things are as difficult as they are rare.”

A Final Note – Too much thinking can be bad too. For instance, there is a well-known connection between rumination and depression. Of course ruminating is obsessive-compulsive, which is unlike the meditative state. If one negatively ruminates when alone with their thoughts, then they are probably better off distracted by activity. This is controversial advice, and I would be happy to hear from readers with other insights.

July 27, 2014

Examples of Great Writing: “The Value of Philosophy”

Yesterday’s column discussed good writing, mentioning the great prose stylists Will Durant and Bertrand Russell. (Who are also two of my intellectual heroes.) Here are examples of their extraordinary prose on the question of the value of philosophy. The first is from the introduction to Durant’s The Pleasures of Philosophy (1929), and the second is from the final chapter of Russell’s classic, The Problems of Philosophy (1912). I’ll let their beautiful prose speak for itself.

The busy reader will ask, is all this philosophy useful? It is a shameful question: we do not ask it of poetry, which is also an imaginative construction of a world incompletely known. If poetry reveals to us the beauty our untaught eyes have missed and philosophy gives us the wisdom to understand and forgive, it is enough, and more than the worlds wealth. Philosophy will not fatten our purses nor lift us to dizzy dignities in a democratic state; it may even make us a little careless of these things. For what if we should fatten our purses, or rise to high office and yet all the while remain ignorantly naive, coarsely unfurnished in the mind, brutal in behavior, unstable in character, chaotic in desire and blindly miserable?

Our culture is superficial today and our knowledge dangerous, because we are rich in mechanism and poor in purposes. the balance of mind which once came of a warm religious faith is gone; science has taken from us the supernatural bases of our morality and all the world seems consumed in a disorderly individualism that reflects the chaotic fragmentation of our character.

We face again the problem that harassed Socrates: how shall we find a natural ethic to replace the supernatural sanctions that have ceased to influence the behavior of men? Without philosophy, without that total vision which unifies purposes and establishes the hierarchy of desires we fritter away our social heritage in cynical corruption on the one hand and in revolutionary madness on the other; we abandon in a moment our idealism and plunge into the cooperative suicide of war; we have a hundred thousand politicians, and not a single statesman.

We move about the earth with unprecedented speed, but we do not know, and have not thought where we are going, or whether we shall find any happiness there for our harrassed souls. We are being destroyed by our knowledge which has made us drunk with our power, and we shall not be saved without wisdom.

And now we hear from Russell:

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find, as we saw in our opening chapters, that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value — perhaps its chief value — through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleagured fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

One way of escape is by philosophic contemplation. Philosophic contemplation does not, in its widest survey, divide the universe into two hostile camps — friends and foes, helpful and hostile, good and bad — it views the whole impartially. Philosophic contemplation, when it is unalloyed, does not aim at proving that the rest of the universe is akin to man. All acquisition of knowledge is an enlargement of the Self, but this enlargement is best attained when it is not directly sought. It is obtained when the desire for knowledge is alone operative, by a study which does not wish in advance that its objects should have this or that character, but adapts the Self to the characters which it finds in its objects. This enlargement of Self is not obtained when, taking the Self as it is, we try to show that the world is so similar to this Self that knowledge of it is possible without any admission of what seems alien. The desire to prove this is a form of self-assertion and, like all self-assertion, it is an obstacle to the growth of Self which it desires, and of which the Self knows that it is capable. Self-assertion, in philosophic speculation as elsewhere, views the world as a means to its own ends; thus it makes the world of less account than Self, and the Self sets bounds to the greatness of its goods. In contemplation, on the contrary, we start from the not-Self, and through its greatness the boundaries of Self are enlarged; through the infinity of the universe the mind which contemplates it achieves some share in infinity.

For this reason greatness of soul is not fostered by those philosophies which assimilate the universe to Man. Knowledge is a form of union of Self and not-Self; like all union, it is impaired by dominion, and therefore by any attempt to force the universe into conformity with what we find in ourselves. There is a widespread philosophical tendency towards the view which tells us that Man is the measure of all things, that truth is man-made, that space and time and the world of universals are properties of the mind, and that, if there be anything not created by the mind, it is unknowable and of no account for us. This view, if our previous discussions were correct, is untrue; but in addition to being untrue, it has the effect of robbing philosophic contemplation of all that gives it value, since it fetters contemplation to Self. What it calls knowledge is not a union with the not-Self, but a set of prejudices, habits, and desires, making an impenetrable veil between us and the world beyond. The man who finds pleasure in such a theory of knowledge is like the man who never leaves the domestic circle for fear his word might not be law.

The true philosophic contemplation, on the contrary, finds its satisfaction in every enlargement of the not-Self, in everything that magnifies the objects contemplated, and thereby the subject contemplating. Everything, in contemplation, that is personal or private, everything that depends upon habit, self-interest, or desire, distorts the object, and hence impairs the union which the intellect seeks. By thus making a barrier between subject and object, such personal and private things become a prison to the intellect. The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge — knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the accidents of private history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses, and dependent, as such knowledge must be, upon an exclusive and personal point of view and a body whose sense-organs distort as much as they reveal.

The mind which has become accustomed to the freedom and impartiality of philosophic contemplation will preserve something of the same freedom and impartiality in the world of action and emotion. It will view its purposes and desires as parts of the whole, with the absence of insistence that results from seeing them as infinitesimal fragments in a world of which all the rest is unaffected by any one man’s deeds. The impartiality which, in contemplation, is the unalloyed desire for truth, is the very same quality of mind which, in action, is justice, and in emotion is that universal love which can be given to all, and not only to those who are judged useful or admirable. Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe, not only of one walled city at war with all the rest. In this citizenship of the universe consists man’s true freedom, and his liberation from the thraldom of narrow hopes and fears.

Thus, to sum up our discussion of the value of philosophy; Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.