John G. Messerly's Blog, page 132

November 11, 2014

Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” Wasn’t Meant to Be Serious

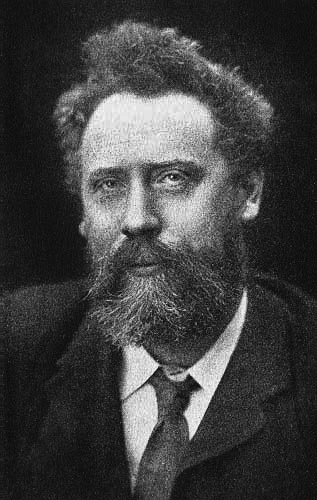

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost

Robert Frost’s poem,”The Road Not Taken,” is probably America’s best-loved poem. What is less well-known is the origin of the poem:

Frost spent the years 1912 to 1915 in England, where among his acquaintances was the writer Edward Thomas. Thomas and Frost became close friends and took many walks together. After Frost returned to New Hampshire in 1915, he sent Thomas an advance copy of “The Road Not Taken.”[1] The poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision, particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together. However, Frost later expressed chagrin that most audiences took the poem more seriously than he had intended; in particular, Thomas took it seriously and personally, and it provided the last straw in Thomas’ decision to enlist in World War I.[1] Thomas was killed two years later in the Battle of Arras.[2]

The tragedy of this misunderstanding is poignant. Thomas was himself a wonderful writer. Here are the final lines from his short story “The Stile.”

I knew that I was more than the something which had been looking out all that day upon the visible earth and thinking and speaking and tasting friendship. Somewhere — close at hand in that rosy thicket or far off beyond the ribs of sunset — I was gathered up with an immortal company, where I and poet and lover and flower and cloud and star were equals, as all the little leaves were equal ruffling before the gusts, or sleeping and carved out of the silentness. And in that company I learned that I am something which no fortune can touch, whether I be soon to die or long years away. Things will happen which will trample and pierce, but I shall go on, something that is here and there like the wind, something unconquerable, something not to be separated from the dark earth and the light sky, a strong citizen of infinity and eternity. The confidence and ease had become a deep joy; I knew that I could not do without the Infinite, nor the Infinite without me.

Edward Thomas was killed on the first day of the battle of Arras, Easter 1917, surviving just over two months in France. He was survived by his wife and three young children. What uselessness is war.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

November 10, 2014

Why Are Sports Fairer than Law and Politics?

It is astonishing the effort exerted in American sports to assure the fairness of their games. Endless replays with camera views from every angle, congressional hearings on whether athletes use performance-enhancing drugs, legal prosecution for alleged betting on performances, and endless scrutiny over the fairness of scheduling, rankings, and post-season participants. New methods to assure fairness on the field are only limited by the current state of technology or how much delay in their entertainment the audience will tolerate. Off the field negotiations involving unions, owners, commissioners, lawyers, and politicians work tirelessly to assure that the games are fair.

Moreover, these standards of fairness and impartiality are often applied more thoroughly than they are in the criminal justice system. There innocent persons are often expeditiously convicted and exonerating evidence withheld—especially for certain kinds of defendants. Perhaps the only exception occurs when the accused are themselves athletes, in which case they sometimes received preferential treatment. If one is lucky enough to have entertainment value, or political power, they stand a much better chance of avoiding the law’s wrath.

Or consider our supposed democracy. In it the wealthiest assure themselves of a disproportionate voice in politics. Yet, at the same time, they make sure that the voices of the masses go unheard, by gerrymandering districts and suppressing voting. Those in power generally ignore that society is unjust to the core. Some individuals have unfair, unmerited advantages that virtually guarantee success, while others are burdened with undeserved obstacles that make success almost impossible. Some can’t lose and others can’t win. But to those weaned on Rand’s The Virtue of Selfishness and its implicit social Darwinism, this all seems normal.

What could possibly explain all this? Why is the position of a football receiver’s toe relative to the sideline often analyzed in greater detail than the crime of one accused of something that carries a life sentence? Why could Congress possibly care so much about whether baseball players like Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens used steroids, but not by action or inaction that condemns thousands to death for lack of health care, from gun violence, or as mercenaries in their wars? Sure sports is profitable and the profiteers want to keep the money flowing. But why do the politically powerful care so much about sports and not about poverty and pain?

The answer is somewhat sinister. Those in power want to make sure their games are “on the up and up” because the entertainment of sports quiets discontent. As Edward Gibbon taught us long ago, the Roman Empire used bread and circuses to control its people. Keep their bellies full and their eyes entertained and they will remain ignorant or apathetic to the injustice that surrounds them. American sports is our circus; it keeps the population mollified. It also inculcates patriotism—flags decorate the players uniforms while both performers and audience are required to stand for the national anthem. This is our civic duty. This is our religion. This helps us forget. This is the opiate of our masses.

Whatever they do those in power want to make sure that we don’t become dissatisfied with our entertainment. If the masses ever did they might become angry. And not that their favorite team had lost again, but with the violence and injustice that surrounds them.

Why Are Sports Fairer than Voting or Courts

It is astonishing the effort American sports exert to assure the fairness of their games. Endless replays with camera views from every angle, congressional hearings on whether athletes use performance-enhancing drugs, legal prosecution for alleged betting on performances, and more. New methods to assure fairness are only limited by the current state of technology or how much delay of the entertainment the audience will tolerate.

These standards of fairness are often greater than those used in the criminal justice system, where innocent persons are expeditiously convicted and exonerating evidence often withheld—especially for certain kinds of defendants—or in our supposed democracy, where great effort is taken to gerrymander districts and suppress voting—especially for certain kinds of voters. Those in power ignore that our society is unjust to the core. Some individuals have unfair, unmerited advantages that virtually guarantee success, while others are burdened with undeserved obstacles that make success almost impossible. Some can’t lose and other can’t win.

What could possibly explain all this? Why is the position of a football receiver’s toe analyzed in greater detail than the crime of one accused of something that carries a life sentence? Why could Congress possibly care about whether baseball players like Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens used steroids, when they don’t mind condemning thousands to death for lack of health care, from gun violence, or as mercenaries in their wars?

The answer is easy. Those in power want to make sure their games are “on the up and up” because the entertainment of sports quiets discontent. As Edward Gibbon taught us long ago, the Roman Empire used bread and circuses to control its people. Keep their bellies full and their minds entertained and they will remain ignorant or apathetic to the injustice that surrounds them. American sports are our circuses; they keep the population mollified. They also inculcate patriotism—flags decorate the players uniforms while both performers and audience are required to stand for the national anthem. This is our civic duty. This is our religion. This helps us forget.

Whatever they do our rulers want to make sure that we don’t become dissatisfied with our entertainment. If the masses ever did, they might instead become disgruntled and angry with the violence and injustice that surrounds them.

November 7, 2014

The Transhumanist Wager

The Transhumanist Wager: Can We and Should We Defeat Death?

The Transhumanist Wager, the brainchild of noted transhumanist Zoltan Istvan, can be understood as follows. If one loves and values their life, then they will want (the option) to live as long as possible. How do they achieve this?

Alternative #1 is to do nothing and hope there is an afterlife. But since you don’t know there is an afterlife, doing nothing doesn’t help your odds.

Alternative #2 is to use science and technology to gain immortality. By doing something you are increasing your odds of being immortal.

So the choice is between bettering your odds or not, and a good gambler will tell you the former is the better choice. At least that’s what the arguments supporters say.

There are two basic obstacles that prevent individuals from taking the wager seriously. First, most people don’t think immortality is technologically possible or, if they do, believe such technologies won’t be around for centuries or millenia. They are simply unaware that research on life-extending and death-eliminating technologies are progressing rapidly. Some researchers think we are only decades from extending life significantly, if not defeating death altogether.

Second, even if convinced that we can overcome death, many feel we shouldn’t. I have written extensively about this topic in my recent book, The Meaning of Life: Religious, Philosophical, Transhumanist, and Scientific Perspectives , and in recent articles, arguing that death should be optional, not mandatory. I never ceased to be amazed how many people—when confronted for the first time with the idea that technology may give them the option of living longer, happier, healthier lives—claim to prefer death. There are many reasons for this, but for most the paradigm shift required is too great, guided as they are by superstition, ancient religion, distorted views of what’s natural, or a general love of stasis and disdain for change—even if it means condemning their consciousness to oblivion!

, and in recent articles, arguing that death should be optional, not mandatory. I never ceased to be amazed how many people—when confronted for the first time with the idea that technology may give them the option of living longer, happier, healthier lives—claim to prefer death. There are many reasons for this, but for most the paradigm shift required is too great, guided as they are by superstition, ancient religion, distorted views of what’s natural, or a general love of stasis and disdain for change—even if it means condemning their consciousness to oblivion!

But for the progressive among us, for those willing to use technology to overcome all human limitations, especially our now infinitesimally small lifespans, I’d like to clarify the transhumanist wager by comparing it to Pascal’s Wager and the Cryonics Wager.

Pascal’s Wager

Pascal’s Wager formulated a pragmatic argument for the existence of the Christian God. Here it is in matrix form:in matrix form:

It’s simple. Bet that god exists and you either win big (heaven) or lose nothing (except perhaps a little time and money), or bet that god doesn’t exist and you either lose big (hell) or win nothing (except perhaps saving a bit of time and money.) The choice is clear. The expected outcome of betting that god exists is infinitely greater than betting the reverse.

The main reason this argument fails is that we don’t know the structure of reality. You might bet on the existence of the Christian God, but in the afterlife you find that Allah or Zeus condemns you for your false beliefs. Or even if the Christian God awaits, you can’t be sure that your version of Christianity is correct. Perhaps only 1 of the approximately 41,000 sects of Christianity is true; the version you believe in is not the correct one; and you will be condemned for your false beliefs.

Or consider another scenario. You believe in the inerrancy of the Bible, go to church, do good deeds, and are awoken at the last judgment by the Christian God. Your feeling pretty good, until you hear a voice say: “I made you in my image by giving you reason. Yet you turned your back on this divine gift, believing in supernatural miracles and other affronts to reason. And you believed in me without good evidence. Begone then! Only scientists and rationalists, those who used the precious gift of reason that I bestowed upon them, can enter my kingdom.”

I don’t know if this scenario is true, but it is as plausible as typical religious explanations of what earns reward and punishment. It may even be more just. The main point is that Pascal’s wager doesn’t work because we don’t know the ultimate nature of reality.

The Cryonics Wager

Now consider the cryonics wager. What happens if I preserve my whole body or my brain? The entire continuum of possibilities looks like this:

I———————————————————-I————————————————————I

awake in a great reality never wake up awake in an awful reality

I might be awaken by post-human descendents as an immortal being in a heavenly world. I might be awakened by beings who torture me hellishly for all eternity. Or I might die and never wake up. Should I make this wager? Should I get a cryonics policy? I don’t know. If I don’t preserve myself cryonically, then I might die and go to heaven, hell, or experience nothingness. If I do preserve myself, as we have just seen, similar results may await me.

In this situation all I can do is assess the probabilities as best I can. Does having a cryonics policy, as opposed to dying and taking my chances, increase or decrease my chances of being revived in a good reality? We can’t say for sure. But if the policy increases that chance, if you desire a blissful immortality, and if you can afford a policy, then you should get one.

Personally I believe that having a cryonics policy increases your chance of being revived in a better reality than dying and taking your chances. I place more faith in my post-human descendants than unseen supernatural beings. Still I can understand others would make a different choice, and we should respect their autonomy to die and hope for the best. In the end we just can’t say for certain what is the best move.

The Transhumanist Wager

Now recall the transhumanist wager:

Do nothing about death -> odds for immortality unaffected.

Do something about death -> odds for immortality improved.

Thus, doing something is better than doing nothing.

The problem is with alternative #2. You don’t know that doing something to eliminate death increases your odds of being immortal. Perhaps there are gods who favor your doing nothing because they think that doing something to defeat death is arrogant. I don’t believe this myself, but its possible. Of course the gods may favor those who try to defeat death too. Moreover, as was previously discussed, even if you do achieve immortality you can’t be sure this state will be desirable. On the other hand, technologically achieved immortality may be wonderful.

Again the problem, as was the case with the other wagers, is that we just don’t know the nature of ultimate reality. No matter what we do, or don’t do, we may reap infinite reward, its opposite, or fade into oblivion. And not knowing the future means that we can never know, from the infinite number of possible outcomes, what the future has in store for us. And that is why none of these wagers are slam dunks.

Conclusion

What I can say with confidence is that if an effective pill that stops or reverses aging becomes available at your local pharmacy—it will be popular. Or if, as you approach death, you are offered the opportunity to have your consciousness transferred to a younger cloned body, a genetically engineered body, a robotic body, or into a virtual reality, most will use such technologies when they are demonstrated effective. By then most people will prefer the real thing to a leap of faith. At that point there will be no need to make a transhumanist wager. The transhumanist will already have won the bet.

November 6, 2014

A Poem About Accepting Death

“Night with Her Train of Stars and Her Great Gift of Sleep”

(This Edward Robert Hughes painting was inspired by William Ernest Henley’s poem “Margaritae Sorori.” The title of the poem is Latin for “sister Margaret.” Henley’s daughter Margaret died when she was five years old.)

Yesterday’s post praised William Ernest Henley’s inspiring poem, “Invictus.” But there is a lesser known Henley poem, “Margaritae Sorori,” that vividly contrasts with the passion and defiance of Invictus. It radiates a contemplative acceptance of death and dying.

A late lark twitters from the quiet skies:

And from the west,

Where the sun, his day’s work ended,

Lingers as in content,

There falls on the old, gray city

An influence luminous and serene,

A shining peace.

The smoke ascends

In a rosy-and-golden haze. The spires

Shine and are changed. In the valley

Shadows rise. The lark sings on. The sun,

Closing his benediction,

Sinks, and the darkening air

Thrills with a sense of the triumphing night–

Night with her train of stars

And her great gift of sleep.

So be my passing!

My task accomplish’d and the long day done,

My wages taken, and in my heart

Some late lark singing,

Let me be gather’d to the quiet west,

The sundown splendid and serene,

Death.

November 5, 2014

Two Poems about Freedom and Circumstances

Philip Larkin (1922 – 1985)

I was thinking about the influence of parents, living or dead, on their adult children. No doubt the impact is significant, and fate deals her hand randomly in such matters. But to what extent can we overcome circumstances, for example parental influence? Philip Larkin wrote the most depressing poem I’ve ever read about parents,

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

I don’t like this poem, and not because I’m afraid to face the nihilistic side of human life. (As anyone who reads this blog can attest.) The first stanza accuses, ok. The second excuses, ok. But the third is deeply problematic.

First, if misery deepens by necessity, which is clearly implied, then we live in a fatalistic universe and all our efforts are pointless. Moreover, in that universe whether we remain childless or commit suicide would also be determined by fate, and there would be no point in advocating for either. For such reasons fatalism has few advocates among philosophers.

Second, if misery does not deepen by necessity, then we have the chance to rectify it. Surely this is a better solution than suicide or childlessness. Larkin may believe that we are better off never having been born, but this doesn’t follow from a soft determinism or compatibilism. The fact that life is less than perfect, doesn’t imply that it isn’t worth living.

William Ernest Henley (1849 – 1903)

Now consider another poem, William Ernest Henley’s classic “Invictus.” (Which is Latin for “unconquered.”) Henley had a difficult life. His family was poor, his father died when he was young and at age twelve tuberculosis necessitated the amputation of one of his legs below the knee. His other foot was later saved only after a radical surgery. Henley was in and out of the hospital from the ages of eighteen to twenty-six, including a continuous three-year span from 1873-1875. He wrote this poem while recovering in the infirmary.

Invictus

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

The stirring finale of this poem is as fresh as the day it was written, still acting as a buttress against encroaching determinism. I have studied the philosophical issue of freedom enough to know that a sustained defense of free will is nearly impossible, but neither can its reverse be definitely established.

So we might as well believe in freedom. For if we have no choice but to believe in the freedom of will, then by necessity we will believe in it. And if we have a choice to believe in freedom of will, then by definition we are free. There is little to lose and much to gain by acting as if we are free, as if we are masters of our fate and captains of our souls.

November 4, 2014

Albert Camus: The Myth of Sisyphus

Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) was a French author, philosopher, and journalist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. His most famous works were the novels La Peste (The Plague) and L’Étranger (The Stranger) and the philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus. He died in a car accident in France.

In “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1955) Camus claims that the only important philosophical question is suicide—should we continue to live or not? The rest is secondary, says Camus, because no one dies for scientific or philosophical arguments, usually abandoning them when their life is at risk. Yet people do take their own lives because they judge them meaningless or sacrifice them for meaningful causes. This suggests that questions of meaning supersede all other scientific or philosophical questions. As Camus puts it: “I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.”

What interests Camus is what leads to suicide. He argues that “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined … the worm is in man’s heart.” When we start to think we open up the possibility that all we valued previously, including our belief in life’s goodness, may be subverted. This rejection of life emanates from deep within, and this is where its source must be sought. For Camus killing yourself is admitting that all of the habits and effort needed for living are not worth the trouble. As long as we accept reasons for life’s meaning we continue, but as soon as we reject these reasons we become alienated—we become strangers from the world. This feeling of separation from the world Camus terms absurdity, a sensation that may lead to suicide. Still most of us go on because we are attached to the world; we continue to live out of habit.

But is suicide a solution to the absurdity of life? For those who believe in life’s absurdity it is a reasonable response—one’s conduct should follow from one’s beliefs. Of course conduct does not always follow from belief. Individuals argue for suicide but continue to live; others profess that there is a meaning to life and choose suicide. Yet most persons are attached to this world by instinct, by a will to live that precedes philosophical reflection. Thus they evade questions of suicide and meaning by combining instinct with the hope that something gives life meaning. Yet the repetitiveness of life brings absurdity back to consciousness. In Camus’ words: “Rising, streetcar, four hours in the office or factory, meal, four hours of work, meal, sleep, and Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday…” Living brings the question of suicide back, forcing a person to confront and answer this essential question.

Yet of death we know nothing. “This heart within me I can feel, and I judge that it exists. This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction.” Furthermore I cannot know myself intimately anymore than I can know death. “This very heart which is mine will forever remain indefinable to me. Between the certainty I have of my existence and the content I try to give to that assurance, the gap will never be filled. Forever I shall be a stranger to myself …” We know that we feel, but our knowledge of ourselves ends there.

What makes life absurd is our inability to know ourselves and the world’s meaning even though we desire such knowledge. “…what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart.”The world could have meaning: “But I know that I do not know that meaning and that it is impossible for me just now to know it.” This tension between our desire to know meaning and the impossibility of knowing it is a most important truth. We are tempted to leap into faith, but the honest know that they do not understand; they must learn “to live without appeal…” In this sense we are free—living without higher purposes, living without appeal. Aware of our condition we exercise our freedom and revolt against the absurd—this is the best we can do.

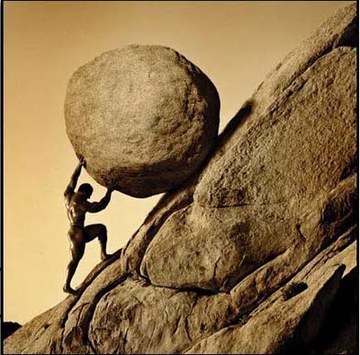

Nowhere is the essence of the human condition made clearer than in the Myth of Sisyphus. Condemned by the gods to roll a rock to the top of a mountain, whereupon its own weight makes it fall back down again, Sisyphus was condemned to this perpetually futile labor. His crimes seem slight, yet his preference for the natural world instead of the underworld incurred the wrath of the gods: “His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing.” He was condemned to everlasting torment and the accompanying despair of knowing that his labor was futile.

Yet Camus sees something else in Sisyphus at that moment when he goes back down the mountain. Consciousness of his fate is the tragedy; yet consciousness also allows Sisyphus to scorn the gods which provides a small measure of satisfaction. Tragedy and happiness go together; this is the state of the world that we must accept. Fate decries that there is no purpose for our lives, but one can respond bravely to their situation: “This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Reflections – Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd yet we can revolt against the absurdity and find some small modicum of happiness. Essentially Camus asks if there is a third alternative between acceptance of life’s absurdity or its denial by embracing dubious metaphysical propositions. Can we live without the hope that life is meaningful but without the despair that leads to suicide? If the contrast is posed this starkly it seems an alternative appears—we can proceed defiantly forward. We can live without faith, without hope, and without appeal.

I believe we are called upon to live without appeal, all appeals are intellectually dishonest. But perhaps there are alternatives between accepting absurdity and hopeful metaphysics besides Camus’ defiance. Perhaps we can embrace realities current absurdity, reject speculative metaphysics, and ground the meaning of our lives in the small part we can play in transforming the world into a more meaningful reality. We reject absurdity, religion, and anger. Instead we work to transform reality.

_______________________________________________________________________

Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” 81.

November 3, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 13 – Kant – Part 2

Diagnosis – Selfishness And Sociality – Kant contrasts non-human animals, who have desires but no sense of duty, and humans who do experience tension between their (self-interested) desires and the demands of the practical reason to do their duty. But how can the interests of others, motivate us to act? Why should we be moral?

Kant argues that reason demands that we be moral. It is our duty to act according to morality rather than our self-interested inclinations and passions. Rational persons should conform their (free) wills to the moral law, which is known to reason through general maxims like the categorical imperative. Being moral is a matter of having the right intention—to follow the moral law—and has nothing to do with the consequences of our actions. We follow the moral law—for example by telling the truth—and disregard whatever consequences may follow. But many people subordinate moral duty to their inclinations, to the desire for their own happiness. Such persons violate the moral law.

As for the source of this immorality, Kant believes on the one hand that we freely choose to disregard our duty, but on the other hand the propensity to evil is somehow innate. The extent to which our evil tendencies are exacerbated by society is open to debate. [What we can say is that something is amiss in human life. We have a duty to others, but we are naturally self-interested.]

Prescription: Pure Religion and Cultural Progress – How then do we overcome selfishness and act morally? Kant dismisses self-interested reasons to be moral—you will be punished if you don’t act appropriately—because such reasons are inconsistent with virtue. For Kant the only thing that is completely good is a good will, the desire or intention to do good for the sake of goodness alone. [While Kant believes the moral law ultimately comes from god, he doesn't emphasize this. Rather he appeals to human reason's ability to know the moral law. Furthermore, Kant argued vehemently in the first critique that the traditional arguments for god’s existence were worthless. Yet he will not rely on fideism either. So where does he go?]

What Kant takes with one hand he gives back with another. While pure reason cannot support the existence of his god, the practical reason can justify beliefs in god, the immortality of the soul, and free will. When we act we presuppose that we are free, and saying one ought to do something implies that they can. What then of god and immortality? Kant argues that the highest good, the end of all our striving, is a combination of moral virtue and happiness. Yet morality is not always rewarded in this life and the evildoers often flourish while the good do not. Thus we need god to rectify the situation. God’s perfect justice will reward and punish. [This is basically the moral argument for god’s existence. 1) There is a moral law, thus 2) there must be a moral lawgiver.] It is important that we have hope that moral virtue will be rewarded, although we are moral not because of these possible rewards, but because being moral is our duty. While Kant did not take a lot of religious imagery literally, but he did hope that justice somehow prevailed. He also thought that practical reason justifiably invokes

Kant also “envisaged continued progress in human culture through education, economic development, and political reform, gradually emancipating people from poverty, war, ignorance, and subjection to traditional authorities … he was a supporter of egalitarian and democratic ideals … [and] he sketched a world order of peaceful cooperation between nations with democratic constitutions.” And Kant expressed hope that human potential could be gradually fulfilled. He was a consummate Enlightenment thinker.

ADDENDUM: BASIC IDEAS IN KANT’S PHILOSOPHY (not from the book we are discussing)

WHAT CAN WE KNOW? (addressed in The Critique of Pure Reason)

Mathematics? Yes, it is legitimate knowledge

Natural science? Yes, it too is legitimate knowledge

Metaphysics? No, we can’t know “things-in-themselves,” we can’t know the nature of ultimate reality, reason isn’t justified in making metaphysical claims.

Still, we want a complete picture of reality, despite the fact that theoretical reason can’t give it to us. This is in part because there exist “antimonies” of reason, the most important of which are the existence of: God; freedom; and immortality. Reason cannot resolve such questions. So what do we do when it comes to action? The realm where ethics applies?

WHAT SHOULD WE DO? (addressed in The Critique of Practical Reason)

First we must presuppose the existence of God and freedom for their to be ethics. Since we have reason and free will we can choose between actions, unlike non-human animals who are guided by instinct. For Kant moral actions are actions where reason leads, rather than follows, instincts. Put more simply we ought to conform our free will to the moral law; that is our duty. The moral law ultimately comes from God but Kant doesn’t stress. Instead he emphasizes that reason can overcome our impulses, the non-rational, instinctive part of our nature, by exercising reason.

Thus Kant says that the only thing that is completely good is a good will, one that tries to conform itself to the moral law which is its duty. This presupposes that we are free to do this. But what do we do when we freely conform our will to the moral law when doing our duty? Kant, as an Enlightenment rationalist, assumes that there must be some rational representation of the moral law that we can all understand. And when he thinks about law, say a physical law, one of the key characteristics of true laws of nature are that they are universal. Thus, the moral law must be characterized by its universality. Just as an equation of the form a(b+c) = ab + ac is universally applicable and needs only to be filled in by numbers, the moral law must have an abstract formulation to be filled in by actions.

This leads to the 1st formulation of the categorical imperative (CI), which is the moral law as understood by reason. This law is binding on all rational being and is such that violation of the moral law also violates reason. He gives four examples of actions that demonstrate how the CI works: lying, suicide, helping others and developing your talents. These are all absolute duties, however the first two are perfect duties while the second two are imperfect duties. This means that satisfying one’s duty in the first two cases can be specified exactly, whereas in the other two there are various ways of doing one’s duty. But the key idea is that one’s duty is the rational action, the one that reason demands. Rational actions are moral actions; irrational actions are immoral ones.

Of course, we can act contrary to reason because we are free, just like we can say that 2 + 2 = 6, or round squares exist, or that there are married bachelors. But we violate reason when we say these things just as the bank robber violates reason when he robs banks. Why? The reason is the same as it is for suicide or lying. One cannot consistently universalize the maxim of one’s actions when one engages in such actions. For example, a bank robber wills a world where:

banks exists as the necessary prerequisite of the bank robbery intended and

banks don’t exist as the obvious consequence of bank robberies.

This is Kant’s essential idea. It violates both reason and ethics to say that I can have a drink of your beer but you can’t have a drink of mine.

To summarize, ethical conduct is that in which the will conforms to the moral law which it understands as the CI and this is its duty. Does this lead to happiness? Not necessarily. Kant says if you want to be happy follow your instincts; if you want to be moral follow the constraints of reason. In this way you should see that Kant doesn’t care about the consequences of actions. Do your duty and whatever happens, happens. So the key is your intention which should be to follow the moral law. Note that this intention is internal to the moral agent, not external like consequences are. You should give someone the correct change—in Kant’s example—because it’s the right thing to do, not because its good for business.

Kant’s criticisms of utilitarianism warrant a separate discussion. Utilitarian moral theories evaluate the moral worth of action on the basis of happiness that is produced by an action. Whatever produces the most happiness in the most people is the moral course of action. Kant has an insightful objection to moral evaluations of this sort. The essence of the objection is that utilitarian theories actually devalue the individuals it is supposed to benefit. If we allow utilitarian calculations to motivate our actions, we are allowing the valuation of one person’s welfare and interests in terms of what good they can be used for. It would be possible, for instance, to justify sacrificing one individual for the benefits of others if the utilitarian calculations promise more benefit. Doing so would be the worst example of treating someone utterly as a means and not as an end in themselves.

Another way to consider his objection is to note that utilitarian theories are driven by contingent inclinations in humans for pleasure and happiness, not by the universal moral law dictated by reason. To act in pursuit of happiness is arbitrary and subjective, and is no more moral than acting on the basis of greed, or selfishness. All three emanate from subjective, non-rational grounds. The danger of utilitarianism lies in its embracing of baser instincts, while rejecting the indispensable role of reason and freedom in our actions.

WHAT CAN I HOPE FOR? – I’ll leave this question for another day. But what I hope is that life is meaningful, that it all somehow works out for the best, that a better reality comes to be.

And so the world goes on,

good gods perpetually sleeping,

good people perpetually weeping,

and waiting, for a new world to dawn.

October 31, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 13 – Kant – Part 1

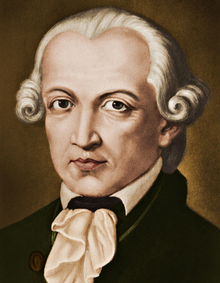

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) is generally considered one of the three or four greatest philosophers in the Western tradition. He lived his entire life in Konigsberg, Prussia which is today the city of Kaliningrad in Russia. Kant’s philosophy is extraordinarily complex but perhaps he was most interested in reconciling Christianity with the science of the Enlightenment.

Kant was quite an accomplished scientist who “developed the nebular hypothesis, the first account of the origin of the solar system by accretion of the planets from clouds of dust.” His education in the humanities was equally impressive “embracing Greek and Latin philosophy and literature, European philosophy, theology, and political theory.” In his university education he was particularly influenced Leibniz, a rationalist who believed that pure reason could prove metaphysical claims, especially those about the existence of god and that we live in the best of all possible worlds. Thus both empiricism and rationalism influenced him, and he spent a lifetime trying to reconcile them.

Kant was the deepest thinker of the European Enlightenment who believed “in the free, democratic use of reason to examine everything, however traditional, authoritative, or sacred … He argued that the only limits on human reason are those that we discover when we scrutinize the pretensions and limitations of reason itself …” His emphasis on the inquiry into the nature and limits of human knowledge meant that epistemology became for him the heart of philosophy. He turned his critical analysis to science, metaphysics, ethics, judgments of beauty and to religion.

Metaphysics, Epistemology, and the Limits of Human Knowledge – A fundamental theme of Kant’s philosophy “was to explain how scientific knowledge is possible.” He argued that “science depends on certain fundamental propositions, for example, that every event has a cause and that something (substance) is conserved through mere change.” These principles cannot be proved empirically but they are not tautologies either. [In Kant's language they are synthetic a priori propositions---propositions whose predicate concept is not contained in its subject concept but related, and propositions whose justification does not rely upon experience. An example of a synthetic proposition is "all bachelors are unhappy." An example of an a priori proposition is "all bachelors are unmarried.] Many philosophers of the time including Leibniz and Hume, as well as many philosophers today deny the possibility of such propositions.] Kant believed that these synthetic a priori propositions “can be shown to be necessary conditions of any self-conscious, conceptualized perceptual experience of an objective world. [In other words we can't have experiences of the world without assuming these propositions are true.]

In the first part of his magisterial Critique of Pure Reason, Kant sets out his theory of how we perceive everything in space and time, and the twelve categories or forms of thought and associated concepts like substance and causality. This leads to the justification for Kant of empirical (a posteriori) knowledge derived from sense experience, and analytical (a priori) knowledge derived from pure reasoning. And, as we saw in the previous paragraph, he also argued that there exist synthetic a priori propositions. Kant famously argued that much of mathematics is in this 3rd box, although many philosophers would argue that mathematics is analytic. Most importantly Kant accepts the existence of an independently existing material world. [Kant is arguing, among other things, that mathematical and scientific knowledge are justified.]

Still Kant argued that how we perceive this external world depends on how the inputs of that world are processed by our cognitive faculties and sensory apparatus. This implies that our cognitive intuitions may “distort our representation of what exists.” And this means we know the world only as it appears to us, not as it really is. Furthermore things as they really are may not even be in space and time! [Thus Kant's Copernican revolution. We are at the center of our reality, structuring it with our minds; our minds are not passive receptors of the external world.]

In the second part of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant argues that “reason tries to go beyond … its legitimate use, when we claim illusory metaphysical knowledge … ( human souls, the universe as a whole, uncaused events, and God.) Such claims go beyond the bounds of human knowledge … we can neither prove nor disprove them; we cannot even acquire probable evidence for or against them.” Thus a decisive break with natural theology. [For Kant theology is not an intellectually justified discipline.] Of course many theologians have responded with fideism (religious belief is justified by faith) but, as we will see, Kant is not in this tradition.

Theory of Human Nature – As we have seen Kant was basically interested in reconciling morality and religion with science. How does human nature fit into this project? For Kant perceptual knowledge depends upon the interaction of “sensory states caused by physical objects and events outside the mind, and the mind’s activity in organizing these data under concepts …” Thus humans interact with the world with their senses and their understanding (reasoning and language.) Reason also plays a special role for human beings—they use it to integrate all their knowledge, in “the scientific search for a unified theory of all natural phenomena.”

In addition to abstract theorizing, reasoning also plays a practical role in Kant’s philosophy. We are agents who do things, who act in the world. But there are not merely causes for what we do, as there are for our non-human animal brethren, we also give reasons for what we do. Sometimes the reason we do thing involves our desires which Kant labels “hypothetical imperatives.” [If you want to be a lawyer, then you ought to go to law school.] But at other times, Kant argues, the reasons for our actions command us independent of our desires as in our moral obligations. We ought to tell the truth or help others even if lying or ignoring them would be in our self-interest. These are examples of what Kant calls “categorical imperatives.” [You ought not lie, even if lying would satisfy some desire you have.] Reason recognizes these categorical imperatives which are the basis of ethics [suicide and lying are bad; helping others and developing your talents are good.]

So what does all this mean for his conception of human nature? Are we dualistic or merely material? Kant leaves the question open, it is irresolvable. [Whether the soul is immortal or not; whether we are free or determined, whether the world in infinite or not, all of these Kant calls "antinomies of reason." That is we can use reason to support either view.] Kant is perhaps most interested in freedom. As for our biological bodies, we are just as determined as other things in the physical world, but because we are rational beings we can act for reasons. We can thus be free. [If we are entirely material beings, this solution probably doesn't work.] Of course while we can see that my reasons give me a reason to act, it is hard to see how rational propositions give me a reason to act. [The latter is what the categorical imperative claims.] Kant does not solve the problem of freedom—nobody else has either—but he does believe that we act “under the idea of freedom.” That is from a practical we necessarily presuppose that we are free. [And the ethical point of view presupposes freedom as well.]

October 30, 2014

4 More Books That Changed My Life

A few days ago I wrote about four books that changed my life before I became a professional philosopher. Today I would like to add four more, of the literally thousands that I’ve read, that transformed me after I became a professional philosopher.

On Human Nature: With a new Preface, Revised Edition

On Human Nature: With a new Preface, Revised Edition

Late in my graduate school career, E.O. Wilson’s On Human Nature was assigned for a graduate seminar in evolutionary ethics. (I’ve written previous posts about Wilson’s thought here and here.) It is the only one of the eight books I’ve selected as most affecting my thought that was assigned for a class. My young mind was startled and transformed by its first few pages.

… if the brain is a machine of ten billion nerve cells and the mind can somehow be explained as the summed activity of a finite number of chemical and electrical reactions, boundaries limit the human prospect—we are biological and our souls cannot fly free. If humankind evolved by Darwinian natural selection, genetic chance and environmental necessity, not God, made the species … However much we embellish that stark conclusion with metaphor and imagery, it remains the philosophical legacy of the last century of scientific research … It is the essential first hypothesis for any serious consideration of the human condition.1

Yes, I knew all this before I read Wilson, but his prose cemented these ideas within me. Evolutionary biology is the key to understanding mind, and to understanding morality and religion as well. Life and culture are thoroughly and self-evidently biological. Yet most people reject these truths, choosing ignorance and self-deception instead. They mistakenly believe that they are fallen angels, not the modified monkeys they really are. But why can they not accept the truth? Because, as Wilson says, most “would rather believe than know. They would rather have the void as purpose … than be void of purpose.”2

Still Wilson’s lesson were not all depressing. Science can liberate us by giving us self-knowledge, while simultaneously placing within us the hope “that the journey on which we are now embarked will be farther and better than the one just completed.”3 Wilson’s book taught me who we are, the dilemmas we face, and how we must choose our future path. The evolutionary idea is the greatest and truest idea that humans have ever discovered.

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

One cannot summarize Carl Sagan’s The Demon Haunted World: Science As A Candle In The Dark, in a few brief paragraphs. One has to read it cover to cover to appreciate it. Sagan’s basic message is that unreason and superstition are dangerous, while science and reason light the world. But its one thing to state this message, it’s another to communicate it so that anyone can understand it. And that’s what Sagan does. If you read this book closely your will learn to despise ignorance and pseudo-science in all their forms.

In the first chapter Sagan quotes Edmund Way Teale “It is morally as bad not to care whether a thing is true or not, so long as it makes you feel good, as it is not to care about how you got your money as long as you have got it.” Right away you know that Sagan cares about what’s true. Sagan continues ” … it is far better to grasp the Universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.” You may disagree, believing instead that the masses need Platonic noble lies or the Grand Inquisitor’s deceptions, but it is clear from reading Sagan that he has a passion, a fetish is you will, for the truth. He will not deceive himself.

We can undermine our reason in a thousand ways, but Sagan will have none of it. For if we infuse our understanding with our prejudices and emotions, we will live in darkness. But if we dispassionately reason with our science, that candle will increasingly illuminate that darkness. This process of illumination is painstakingly slow, but illumination comes to those who persist. Let there be light.

Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is the most emotionally moving text that I have ever read. I have taught out of it on many occasions and have read it cover to cover at least five times. Anyone can read the first part of the book, “Experiences in a Concentration Camp,” or its second part, “Logotherapy in a Nutshell,” in a few hours. But the book is worth returning to over and over again to be reminded of its central lesson—that meaning can be found in our work, our relationships, and our suffering. Yet nothing that I write does justice to the experience of reading this book—its power lies in its narrative.

So let me describe a single scene in the book. Being marched off to work one dark morning, cold and hungry, while being hit with the butt or rifles by the Nazi guards, a fellow prisoner says to Frankl, “If our wives could see us now! I do hope they are better off in their camps and don’t know what is happening to us.” This exchange caused Frankl to think about his wife, her face, her smile, her look. He writes:

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth—that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which a man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of human is through love and in love. I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for the brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when a man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way-an honorable way-in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, “The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory.

Afterword – In 1942, Frankl, his wife, and his parents were deported to the Nazi Theresienstadt Ghetto where his father died. In 1944 Frankl and his wife Tilly were transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, but Tilly was later transferred from Auschwitz to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she died in the gas chambers. Frankl’s mother Elsa was killed in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, where his brother Walter also died. Other than Frankl, the only survivor of the Holocaust among his immediate relatives was his sister Stella. She had escaped from Austria by emigrating to Australia.4

And so the world goes on,

good gods perpetually sleeping,

good people perpetually weeping,

and waiting, for a new world to dawn.

The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence

The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence

There is no book that can be profound in the way that Frankl’s book is. But a book can change you in a different way. Before I read Kurzweil, I thought about prospects for improving humanity in terms of genetic engineering. But Kurzweil made me see another way to transform the species—through artificial intelligence and robotics—and with it a new vision of the future appeared. Yes, some of Kurzweil’s prediction may not come true, the future is hard to predict. But the broad outlines of his vision are already coming true.

With the caveat that many things can derail technological evolution—asteroids, viruses, climate change, nuclear war, a new dark ages—if scientific advance continues, the future will be unlike the past. Let me embellish that. The future is going to be really different than the past. Perhaps everyone knows that, but Kurzweil convinced me of it. He also showed me how universal death is avoidable. Nobody had ever done that before.

So will the Universe end in a big crunch, or in an infinite expansion of dead stars, or in some other manner? In my view, the primary issue is not the mass of the Universe, or the possible existence of antigravity, or of Einstein’s so-called cosmological constant. Rather, the fate of the Universe is a decision yet to be made, one which we will intelligently consider when the time is right.5

I have written an entire book, The Meaning of Life: Religious, Philosophical, Transhumanist, and Scientific Perspectives , one of whose central themes is that life can only have full meaning if it persists indefinitely. Kurzweil was the first to suggest to me how this was scientifically possible.

, one of whose central themes is that life can only have full meaning if it persists indefinitely. Kurzweil was the first to suggest to me how this was scientifically possible.

I will never reading this book on a screened-in front porch in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. It bent my mind in a new direction.

___________________________________________________________________________

1. Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) 1-2.

2. Wilson, On Human Nature, 170-171.

3. Wilson, On Human Nature, 209.

4. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viktor_F...

5. Ray Kurzweil, The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence (New York: Viking Press, 1999) 260.