John G. Messerly's Blog, page 131

November 19, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 17 – Freud – Part 2

Prescription: Psychoanalytic Therapy – Freud hoped “that human problems could be diagnosed and ameliorated by the methods of science. His project was to restore a harmonious balance between parts of the mind and … to suggest a better balance between individuals and the social world.” Freud concentrated on the former—social reformers work on the latter—but he recognized the limits of working only with patients. Freud’s method, so well known to us today, was to get his patients talking uninhibitedly about their past. When patients stopped talking Freud believed this meant he was close to some memory or idea that was unconsciously repressed. He thought that by bringing this material to the awareness of the rational, conscious mind, one could defeat these harmful thoughts.

Freud realized this process could take years, but such “psychotherapy” could eventually bring greater harmony for troubled individuals. Yet he also found that patients manifested strong feelings of love or hatred toward Freud himself. Thus was born the idea of “transference,” whereby emotions are projected onto the therapist. The goal of the therapy is self-knowledge. Patients may then: a) replace repression of instinctual wishes with rational self-control; b) divert them into acceptable behaviors; or c) even satisfy the wishes. But by bringing these passions to the surface one conquers them, they no longer will control the patient. And Freud also thought that psychoanalysis could probably be applied to entire societies: “… our civilization imposes an almost intolerable pressure on us …” [For example what does it say about a country that always says it is #1, or the greatest country on earth, when by objective measures it clearly is not the best place to live, does not have the happiest people, has a very high suicide rate, has the highest incarceration rates, etc.? Might Freud say the entire culture is neurotic?]

Critical Discussion: (A) Freud As Would-Be Scientist – Is psychoanalytic theory scientific? Is it effective? Is it true?

Is it effective? – It is hard to judge the effectiveness of psychoanalysis for many reasons. First understanding the causes of maladaptive behavior or thought—abuse in childhood—does not imply that one can change it, some things may be impossible to undo and we have to accept or control them as best we can. Second even if psychoanalysis works, it might be misapplied in practice. Third what constitutes a cure is vague. Fourth how can we compare different neurotic patients, or establish control groups to compare them to? Generally we rely on anecdotal evidence about the effectiveness of therapy, which is by definition not scientific.

Is it true? – Testability is fundamental for a theory to have scientific status, so we must ask whether these theories are testable before we can know if they are true. Freud’s theorizing is speculative, going beyond the evidence, so it is not clear how it is testable. For example, Freud thought dreams were typically to be understood as wish-fulfillment. Even if this is true what are its causes? Are they mental or physical? Are dreams significant or just cognitive noise? Can we test the idea that the cause of a dream is a wish? [Neurophysiology can speak to this much better now.] Can we test that the unconscious is the cause of a slip of the tongue, a Freudian slip? Isn’t psychoanalytic theory just a way to understand people by interpreting meaning into what they say, do, and dream? In large part it seems so.

Now consider the idea of unconscious mental states. Is it a testable idea? Does it explain or predict human behavior? If not it is not scientific. It is similar to our attributing conscious states to explain thoughts and behaviors. [Many scientists think this is just a kind of “folk” psychology, explanations that aren’t really scientific ones.] Moreover Freud does more than just postulate unconscious states, he says the process of repression pushes thoughts into the unconscious. But who or what does this repressing? Is this another consciousness? Is there a consciousness within a consciousness?

Defenders reply that psychoanalytic theory is not so much a scientific hypotheses as a hermeneutic (interpretation), a way to understand the meaning of people’s actions, words, dreams, neuroses, etc. We shouldn’t criticize it for being less precise than physics or chemistry. People are complicated! Interpretations of people are more art than science. And a good psychotherapist is particularly good at understanding human motivation. Still it seems that interpretations should be backed up with evidence before we accept it as a good interpretation. Perhaps this hermeneutic view can be supported by the distinction between reasons and causes. Maybe the unconscious is not a physical cause but a psychological reason for behavior. Or perhaps unconscious beliefs and desires are both causes and reasons. These are deep philosophical questions.

As for Freudian drives, how many there are? How are they to be distinguished from one another? How do we know that some drive, say a sexual one, is behind different behaviors, say artistic expression? We can sometimes be self-destructive, but does this imply we have a death instinct? None of this is clear.

Critical Discussion: (B) Freud As Moralist – All human behaviors don’t seem driven by bodily needs. But Freud thought that our behavior shows we operate according to “the pleasure principle.” We generally seek satisfaction of our impulses. But this makes us seem exactly like non-human animals despite the fact that we derive so much satisfaction from, for example, the intellectual and artistic. Freud replied that these “satisfactions are mild” compared to eating, drinking, and sex. Moreover the higher satisfactions are available only to those with rare gifts he thought. [I’m surprised he doesn’t make more of Plato or John Stuart Mill’s distinctions between the qualities of pleasures. Both thought the intellectual much preferable.] But what of the satisfaction of friendship, parenting, music and more which are more reliable and lasting forms of satisfaction. Perhaps Freud’s views were colored by the physical pain he endured and the times of world war through which he lived.

But Freud was not one to offer an overly optimistic view of reality. For example he saw “religious belief as a projection onto the universe of our childhood attitudes to our parents: we would like to believe that our Heavenly Father … is also in benevolent control of our lives …” Freud thought religion appealed to the emotions not reason. Of course that fact that religion has its origins in childhood doesn’t mean that it’s false but Freud himself was an atheist who thought religion was generally bad for society. [He also thought that religion could be understood as wish-fulfillment, we believe in things like immortality that we wish to be true. But again that doesn’t mean that’s its false.]

Freud also believed that saintly, selfless behavior as well as artistic or scientific activity derived their energy from suppressed sexual instincts. Needless to say this biological theory of human motivation is highly speculative. Human are often bored even if their physical needs are met. But Freud thought that most humans are motivated by pleasure and thus they may need Platonic-like guardians to run the society.

November 18, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 17 – Freud – Part 1

Freud: The Unconscious Basis of Mind

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature. )

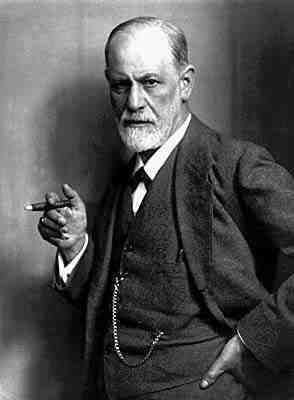

“Freud’s psychoanalytic approach to the mind revolutionized our understanding of human nature in the first half of the twentieth-century.” Freud (1856 – 1939) grew up in Vienna where he lived until the last year of his life. He was an outstanding student with a broad range of academic interests, he attended the University of Vienna medical school, and worked as a physician before setting up a private practice in nervous disorders at the age of thirty. He continued that work for the rest of his life.

In the first phase of his intellectual career “he put forth some original hypotheses about the nature of neurotic problems, and began to develop his distinctive method of treatment, which came to be known as psychoanalysis.” From his early experiences conducted with middle-class Viennese woman, Freud hypothesized that emotional symptoms had their roots in a long-forgotten emotional trauma that needed to be recalled so that the emotions associated with it could be discharged. [This mechanical model is itself problematic. Do humans build up pressure like machines? Is there a better model to describe them?] This was the beginning of the idea of psychoanalysis. Freud also found that in many cases that patients reported their trauma originated in sexual abuse—although he was uncertain how often these reports were reliable. Freud postulated that psychology had a physical basis in the brain, but neurophysiology was not developed enough at the time to confirm this.

Around the turn of the century he also began to formulate theories about sexual development and the interpretation of dreams. Ideas common to our lexicon would subsequently spring up—resistance, repression, and transference. Such ideas were applied to everyone’s mental life, giving birth to a new psychological theory. Starting around 1920, Freud changed his theories introducing the death and life instincts, as well as his division of the mind into the id, ego, and superego. In his later years he wrote his most philosophical works. The Future of an Illusion regarded religion “as a system of false beliefs whose deep infantile root in our minds can be explained psychoanalytically.” While Civilization and Its Discontents “discussed the alleged conflict between individual drives and the morals of civilized society.”

The Future of an Illusion

The Future of an Illusion

Civilization and Its Discontents

Civilization and Its Discontents

Freud escaped Austria right before the start of World War II and died a year later in London. [Freud suffered terribly from cancer of the jaw in the final months of his life. On September 21 and 22 his doctor administered the doses of morphine, as he had promised and Freud requested, that resulted in Freud's death on 23 September 1939.]

Metaphysical Background: Neuroscience, Determinism, and Materialism – Freud began his career as a physiologist who always tried to explain all phenomena scientifically. He had no use for theology or transcendent metaphysics, believing instead that the human condition could be improved by the application of science and reason. Living post-Darwin, Freud recognized that human beings are animals related to all living things, and he believed that both mental and physical events are determined by physical causes. This meant that Freud was a materialist regarding mind—as almost all philosophers and scientists are today—mental states, including unconscious states, are dependent upon brain states. He left the project of discovering the relationship of mental states and the brain to future scientists, a project that has developed enormously since his time.

Theory of Human Nature: Mental Determinism, The Unconscious, Drives, and Child Development – The first major idea in Freud’s theory of human nature is the application of determinism to psychology. This would seem to imply that humans do not possess free will, but Freud was ambivalent about that philosophical question. On the one hand he thought the contents of consciousness are determined by individual, psychological and biological drives, while on the other hand he believed that we sometimes make rational decisions and judgments. (This is similar to Marx’s view, although Marx held that the causes of the contents of our consciousness were primarily social and economic.)

The second key idea in Freud’s theorizing is the postulation of the unconscious. For Freud there are not only preconscious states, those we aren’t continually conscious of but can recall if needed, but unconscious states that can’t ordinarily become conscious. Our minds contain elements of which we have no awareness, but which exert influence on us nonetheless. Some elements of the unconscious may have originally been conscious, say a traumatic event in childhood, but were subsequently repressed—a process of pushing ideas into the unconscious. [Is this is done consciously or unconsciously?] He also advanced his famous three-part division of the structure of the mind: 1) id, instinctual drives that seek immediate satisfaction according to the pleasure principle; 2) ego, conscious mental states governed by a reality principle; and 3) superego, the conscience, which confronts the ego with moral rules or feeling of guilt and anxiety. The ego tries to reconcile the conflicting demands of the id—I want candy—with the superego—you shouldn’t steal candy.

The third main idea in Freud is his focus on drives or instincts. These drives manifest themselves in multiple ways. Freud, following the mechanical models of his day, felt these drives need to be discharged or pressure builds up. [Again this is at best a model, and probably not a good one.] Freud emphasized the sexual drive to a much greater extent than any previous thinker, but other important drives include the drive for self-preservation and other life-enhancing drives (eros), as well as self-destructive drives for sadism, aggression or death instinct (Thanatos). However Freud acknowledged these ideas were preliminary.

The fourth major aspect of Freud’s theorizing was his offering of a developmental account of human personalities. He places particular emphasis on the crucial importance of childhood for future psychological development. [Be nice to your children.] In fact he didn’t believe you could understand any adult without knowing about facets of their childhood, including various sexual stages of development. And while Freud has been criticized for his focus on the Oedipus complex, most likely he was making the point that the love between parents and children foreshadowed adult love. However if individuals don’t develop properly then psychoanalysis may be the only way one can reverse the damage of childhood.

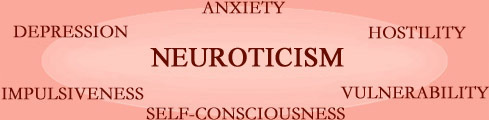

Diagnosis: Mental Harmony, Repression, and Neurosis – “Like Plato, Freud held that individual well-being, happiness, or mental harmony depends on a harmonious relationship between various parts of the mind, and between the whole person and society.” [This might explain why some countries---most notably, New Zealand, Switzerland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Finland, and Denmark---do so much better than other countries on the Social Progress Index.] The ego seeks to satisfy its demands, but if there is a dearth of opportunities to do this, pain and frustration ensue. Yet even in the best of situations there is obsession, neuroticism, and other mental illness.

Freud believed that repression was a primary cause of neuroticism. If someone experiences drives or desires (or beliefs) that conflict with standards or norms they are supposed to adhere to, then such feelings are often repressed. Repression is a defense mechanism used to avoid mental conflict. But repression ultimately doesn’t work, for the desires or drives remain in the unconscious exerting their influence. They may lead to irrational behaviors that we cannot control. Furthermore much of the blame for neuroses Freud attributes to the social world. Parents and other parts of culture may make unrealistic demands upon people. In fact Freud speculated that entire societies can be described as neurotic. While the exact meaning of this claim is ambiguous, clearly some societies do better at providing the conditions in which individuals can flourish.

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 16 – Freud – Part 1

Freud: The Unconscious Basis of Mind

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature. )

“Freud’s psychoanalytic approach to the mind revolutionized our understanding of human nature in the first half of the twentieth-century.” Freud (1856 – 1939) grew up in Vienna where he lived until the last year of his life. He was an outstanding student with a broad range of academic interests, he attended the University of Vienna medical school, and worked as a physician before setting up a private practice in nervous disorders at age thirty. He continued that work for the rest of his life.

In the first phase of his intellectual career “he put forth some original hypotheses about the nature of neurotic problems, and began to develop his distinctive method of treatment, which came to be known as psychoanalysis.” From his early experiences conducted with middle-class Viennese woman, Freud hypothesized that emotional symptoms had their roots in a long-forgotten emotional trauma that needed to be recalled so that the emotions associated with it could be discharged. This was the beginning of the idea of psychoanalysis. Freud also found that in many cases that patients reported their trauma originated in sexual abuse—although he was uncertain how often these reports were reliable. And Freud postulated that psychology had a physical basis in the brain, but neurophysiology was developed enough at the time to confirm this.

Around the turn of the century he also “began to formulate his distinctive theories about infantile sexuality and the interpretation of dreams.” Ideas common to our lexicon would subsequently spring up—resistance, repression, and transference. Such ideas were applied to everyone’s mental life and thus a new psychological theory was being born. Starting around 1920 Freud made important changes to his theories introducing the death and life instincts, as well as his famous division of the mind into the id, ego, and superego. In his later years he wrote his most philosophical works. The Future of an Illusion regarded religion “as a system of false beliefs whose deep infantile root in our minds can be explained psychoanalytically.” While Civilization and Its Discontents “discussed the alleged conflict between individual drives and the morals of civilized society.” Freud escaped Austria right before the start of World War II and died a year later in London. [Freud suffered terribly from cancer of the jaw in the final months of his life. On September 21 and 22 his doctor administered the doses of morphine, as he had promised and Freud requested, that resulted in Freud's death on 23 September 1939.]

Metaphysical Background: Neuroscience, Determinism, and Materialism – Freud began his career as a physiologist who always tried to explain all phenomena scientifically. He had no use for theology or transcendent metaphysics, believing instead that the human condition could be improved by the application of science and reason. Living post-Darwin, Freud recognized that human beings are animals related to all living things, and he believed that both mental and physical events are determined by physical causes. This meant that Freud was a materialist regarding mind—as almost all philosophers and scientists are today—mental states, including unconscious states, are dependent upon brain states. He left the project of discovering the relationship of mental states and the brain to future scientists, a project that has developed enormously since his time.

Theory of Human Nature: Mental Determinism, The Unconscious, Drives, and Child Development – The first major idea in Freud’s theory of human nature is the application of determinism to psychology. This would seem to imply that humans do not possess free will but Freud was ambivalent about that philosophical question. On the one hand he thought the contents of consciousness are determined by individual, psychological and biological drives, while on the other hand he seemed to think we sometimes make rational decisions and judgments. (This is similar to Marx’s view, although Marx held that the causes of the contents of our consciousness were primarily social and economic.)

The second key idea in Freud’s theorizing is the postulation of the unconscious. For Freud there are not only preconscious states, those we aren’t continually conscious of but can recall if needed, but unconscious states that can’t ordinarily become conscious. Our minds contain elements of which we have no awareness but which exert influence on our thoughts and behaviors. Some elements of the unconscious may have originally been conscious, say a traumatic event in childhood, but they have often been repressed—a process of pushing ideas into the unconscious. [I wonder if this is done consciously or unconsciously.] He also advanced his famous three-part division of the structure of the mind: 1) id, instinctual drives that seek immediate satisfaction according to the pleasure principle; 2) ego, conscious mental states governed by a reality principle; and 3) superego, the conscience, which confronts the ego with moral rules or feeling of guilt and anxiety. The ego tries to reconcile the conflicting demands of the id—I want candy—with the superego—you shouldn’t steal candy.

The third main idea in Freud is his focus on drives or instincts. These drives can manifest themselves in multiple ways. Freud, following the mechanical models of his day, felt these drives need to be discharged or pressure builds up. [Note how thoroughly this notion influences modern discussion of drives, even though it is at best a model and probably not a good one.] Freud emphasized the sexual drive to a much greater extent than any previous thinker, but other important drives include the drive for self-preservation and other life-enhancing drives (eros), as well as self-destructive drives for sadism, aggression or death instinct (Thanatos). However Freud acknowledged his work here was preliminary.

The fourth major aspect of Freud’s theorizing was his offering of a developmental account of human personalities. He places particular emphasis on the crucial importance of childhood for future psychological development. [Be nice to your children.] In fact he didn’t believe you could understand any adult without knowing about many of the facets of their childhood, including various sexual stages of development. And while Freud has been criticized for his focus on the Oedipus complex, most likely he was making the point that the love between parents and children “contains the seed from which adult love … can grow.” However, if individuals don’t develop properly then psychoanalysis may be the only way one can reverse the damage of childhood. [Obviously this is all controversial.]

Diagnosis: Mental Harmony, Repression, and Neurosis – “Like Plato, Freud held that individual well-being, happiness, or mental harmony depends on a harmonious relationship between various parts of the mind, and between the whole person and society.” [This might explain why some countries---most notably, New Zealand, Switzerland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Finland, and Denmark---do so much better than other countries on the Social Progress Index.] The ego seeks to satisfy its demands, but if there is a dearth of opportunities to do this, we experience pain and frustration. Yet even in the best of situations there is obsession, neuroticism, and other mental illness.

Freud believed that repression was a primary cause of neuroticism. For example if someone experiences drives or desires (or beliefs) that conflict with standards or norms they are supposed to adhere to, then such feelings are often repressed, a defense mechanism to avoid used to avoid mental conflict. But repression ultimately doesn’t work, for it remains in the unconscious exerting its influence. It may lead to irrational behaviors that we cannot control. Furthermore much of the blame for neuroses Freud attributes to the social world. Parents and other parts of culture may make unrealistic demands upon people. In fact Freud speculated that entire societies can be described as neurotic.

November 17, 2014

Hang in There (A Poem for the Distressed)

Hang in There

Like a boxer staggering

on the ropes,

don’t condemn yourself for being hit

praise yourself for fighting,

maintain your hope.

You are a champion but sometimes

you must get out of the ring,

there are better things in life than boxing

And after winter comes the spring.

But after spring

the winter will come again you say,

perhaps, but perhaps not

Life is mysterious.

November 15, 2014

Death Is Like A Ticking Time Bomb

I have written extensively on why: 1) we should use technology to defeat death; 2) death is one of the greatest tragedies to befall us; and 3) death makes completely meaningful lives impossible. In my recent post I summarized Nick Bostrom’s story that makes similar points. In response I received this perceptive comment:

Love that story. Given that we now see death as a result of genetic programming. Literally, programmed cell death. You could tell a similar story but have everyone born with a ticking time bomb strapped to them. same point but more accurate. People of the religious or “death gives life meaning” crowd would be arguing against disarming this bomb.

The “ticking time bomb” conveys the sense in which death is always with us, not merely at the end of the road like the dragon-tyrant. In Bostrom’s image you stand in line awaiting your fate—which is bad enough—but strapped to a ticking time bomb you can blow up anytime, which is a more accurate description of our situation. Death is always near.

The deathists—the lovers of death—don’t disarm the bomb because its detonation transports you to a better address—from a slum to a mansion. Even better, in the mansion your mind and body are eternally bathed in a salve of peace, love, and joy. That is the justification for opposing the bomb’s removal.

The problem is this story is fictional. And we know that most people agree because, as I’ve said many times in my blog and books, when humans conquer death, slay the dragon-tyrant, and learn to remove the bomb—they will. And those who have the option to live forever will be eternally grateful that they have the real thing, instead of the empty promises they now pay for each Sunday in church.

Consciousness has come a long way from its beginnings in a primordial soup … but there is so much farther to go. Let’s put our childhood behind us, and make something of ourselves.

I say no man has ever yet been half devout enough;

None has ever yet adored or worship’d half enough;

None has begun to think how divine he himself is,

And how certain the future is.

O strain, musical, flowing through the ages—now reaching hither!

I take to your reckless and composite chords—I add to them,

And cheerfully pass them forward.

~ Walt Whitman

November 14, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 16 – Marx – Part 2

Theory of Human Nature: Economics, Society, and Consciousness – Marx is most interested in the social nature of humans rather than their biological nature. “Almost everything a person does presupposes the existence of other people … what kinds of things one does are affected by one’s interactions in the society one lives in. What seems ‘instinctive’ in one society or epoch—for example, a certain role for women—may be very different in another.” In other words, sociology is not reducible to biology or psychology. Some things about humans cannot be explained by facts about individuals but must be explained by society. Marx is one of the founding fathers of sociology. Marx does argue that human beings are active, productive beings. Unlike non-human animals, we make conscious decisions about how we want to work for a living, and good lives entail appropriate, purposive work.

Diagnosis: Alienation and Exploitation Under Capitalism – Alienation or estrangement in Marx refers to our alienation from other people, as well as from the products and process of their labor. Without capital one must sell one’s labor to capitalists who dictate the nature of work. Thus we do not generally get to express or elaborate our being through our work but must work in order to satisfy our basic needs. At work we don’t “belong to ourselves,” rather we are under the control of others. Moreover “the competitiveness of life under capitalism conflicts with the ideal of solidarity with other human beings.” Alienation thus implies a lack of community where individuals can’t see their work as contributing to the larger society. In short Marx sees the economic structure of capitalism as unjust. [What would he think of this?]

Surprisingly many of Marx insights coincide with those of Adam Smith, who is usually hailed as the father of capitalism and its most ardent defendant. Smith too was alarmed by the injustice of capitalism: “No society can surely be flourishing and happy of which by far the greater part of the numbers are poor and miserable.” Both echo Kant’s a formulation of the categorical imperative—never treat people as a means to an end, for they are ends in themselves. In Marx’s time people were clearly used for the capitalists end, including children and adults who worked long hours in unsafe conditions. [Thee conditions were not ameliorated by capitalists, but by responsive governments.] Even today exploitation of workers in the most advanced countries still takes place. [The countries that do this least, who treat their workers best, are the social democracies of Scandinavia and western Europe.] And this is not only factory workers or minimum wage workers but the vast majority of people who can’t fulfill their human potential, those who cannot elaborate themselves through their labor. Human beings shouldn’t exist as cogs in a productive machine; they produce in order to express themselves.

Prescription: Revolution and Utopia – “If alienation and exploitation are social problems caused by the nature of the capitalist system, then the solution is to abolish that system and replace it with a better one.” [A more modest proposal would be to tinker with it, preserving what might be good about it but improving its obvious flaws---encouraging mindless consumption, exploitation of individuals, destruction of the environment, etc.] Marx thought that the movement of history would eventually undermine capitalism. [In fact pure laissez-faire capitalism exists nowhere on the planet.] However he still believed that we should act to bring about the transition from capitalism to communism (a classless society in which all wealth and property is jointly owned). Marx held that a complete revolution was necessary to undermine capitalism and create a more just and equitable society. [Some historians argue that US President FDR actually saved capitalism from the ferment developing in the depression of the 1930s.) In fact many of the proposals of the Communist Manifesto have been adopted by capitalist countries.

“Marx envisaged a total regeneration of humanity …” If human consciousness could be altered, then freedom could become real, with individuals free to actualize their potentials. The guiding principle of this world is “from each according to [their] ability, to each according to [their] needs.” [If this sounds idealistic, think of the voluntary labor that produced Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook, etc] Marx advocated using science and technology to improve life, shortening work, universal education, society in balance with nature, and more. “Marxism has offered this kind of hopeful vision of a human future … [it] has been a secular faith, a prophetic vision of social salvation.”

Still we might object that economic factors are “only one of many obstacles in the way of human fulfillment.” Existential angst, immorality, illness, aggression, mortality and much more also stand in its way.

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 15 – Marx – Part 2

Theory of Human Nature: Economics, Society, and Consciousness – Marx is most interested in the social nature of humans rather than their biological nature. “Almost everything a person does presupposes the existence of other people … what kinds of things one does are affected by one’s interactions in the society one lives in. What seems ‘instinctive’ in one society or epoch—for example, a certain role for women—may be very different in another.” In other words, sociology is not reducible to biology or psychology. Some things about humans cannot be explained by facts about individuals but must be explained by society. Marx is one of the founding fathers of sociology. Marx does argue that human beings are active, productive beings. Unlike non-human animals, we make conscious decisions about how we want to work for a living, and good lives entail appropriate, purposive work.

Diagnosis: Alienation and Exploitation Under Capitalism – Alienation or estrangement in Marx refers to our alienation from other people, as well as from the products and process of their labor. Without capital one must sell one’s labor to capitalists who dictate the nature of work. Thus we do not generally get to express or elaborate our being through our work but must work in order to satisfy our basic needs. At work we don’t “belong to ourselves,” rather we are under the control of others. Moreover “the competitiveness of life under capitalism conflicts with the ideal of solidarity with other human beings.” Alienation thus implies a lack of community where individuals can’t see their work as contributing to the larger society. In short Marx sees the economic structure of capitalism as unjust. [What would he think of this?]

Surprisingly many of Marx insights coincide with those of Adam Smith, who is usually hailed as the father of capitalism and its most ardent defendant. Smith too was alarmed by the injustice of capitalism: “No society can surely be flourishing and happy of which by far the greater part of the numbers are poor and miserable.” Both echo Kant’s a formulation of the categorical imperative—never treat people as a means to an end, for they are ends in themselves. In Marx’s time people were clearly used for the capitalists end, including children and adults who worked long hours in unsafe conditions. [Thee conditions were not ameliorated by capitalists, but by responsive governments.] Even today exploitation of workers in the most advanced countries still takes place. [The countries that do this least, who treat their workers best, are the social democracies of Scandinavia and western Europe.] And this is not only factory workers or minimum wage workers but the vast majority of people who can’t fulfill their human potential, those who cannot elaborate themselves through their labor. Human beings shouldn’t exist as cogs in a productive machine; they produce in order to express themselves.

Prescription: Revolution and Utopia – “If alienation and exploitation are social problems caused by the nature of the capitalist system, then the solution is to abolish that system and replace it with a better one.” [A more modest proposal would be to tinker with it, preserving what might be good about it but improving its obvious flaws---encouraging mindless consumption, exploitation of individuals, destruction of the environment, etc.] Marx thought that the movement of history would eventually undermine capitalism. [In fact pure laissez-faire capitalism exists nowhere on the planet.] However he still believed that we should act to bring about the transition from capitalism to communism (a classless society in which all wealth and property is jointly owned). Marx held that a complete revolution was necessary to undermine capitalism and create a more just and equitable society. [Some historians argue that US President FDR actually saved capitalism from the ferment developing in the depression of the 1930s.) In fact many of the proposals of the Communist Manifesto have been adopted by capitalist countries.

“Marx envisaged a total regeneration of humanity …” If human consciousness could be altered, then freedom could become real, with individuals free to actualize their potentials. The guiding principle of this world is “from each according to [their] ability, to each according to [their] needs.” [If this sounds idealistic, think of the voluntary labor that produced Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook, etc] Marx advocated using science and technology to improve life, shortening work, universal education, society in balance with nature, and more. “Marxism has offered this kind of hopeful vision of a human future … [it] has been a secular faith, a prophetic vision of social salvation.”

Still we might object that economic factors are “only one of many obstacles in the way of human fulfillment.” Existential angst, immorality, illness, aggression, mortality and much more also stand in its way.

November 13, 2014

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 15 – Marx – Part 1

Marx: The Economic Basis of Society

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature. )

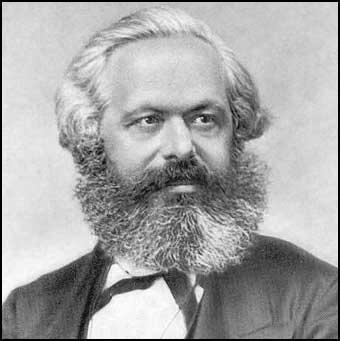

We are interested in Marxist theory, not in the various ways it may have been implemented. [Think of the parallel with Christianity. If you are a Christian and someone says "Christians conducted the Crusades and Inquisition, they may have collaborated with the Nazis and protected pedophile priests," you answer that none of that is Christian behavior. A Marxist can say the same about Stalin or Mao or North Korea.] Who was Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)? “Marx was the greatest critical theorist of the Industrial Revolution and nineteenth-century capitalism … Although hostile to religion, Marx inherited an ideal of human equality and freedom from Christianity, and he shared the Enlightenment hope that scientific method could diagnose and resolve the problems of human society … Behind his … theorizing was a prophetic, quasi-religious zeal to show the way toward a secular form of salvation.”

Hegel

Marx studied at the University of Berlin in the mid nineteenth-century at a time and place when G.W.F. Hegel’s thought was dominant. Hegel believed in a progressive human history where Geist—mind, spirit or god—develops throughout history. All human history is “the progressive self-realization of Geist.” In other words human social life evolves in a progressive direction as more adequate ideas of reality slowly emerging leading to greater consciousness, self-awareness and freedom. [Hegel’s philosophy is notoriously complex and abstruse. But the process in large part takes place as a dialectic between ideas. A thesis is offered, its antithesis advanced, and a synthesis emerges.] Hegel believed that mental and cultural development eventually reaches a state of absolute knowledge. Right Hegelians believed that the 19th Prussian state had reached a near perfect state of development; left Hegelians believed it had not, that the society was far from ideal and it was up to people to make it better.

[Consider the parallels with politics in the USA today. From the conservative right we hear that “the USA is the greatest nation ever,” “American love it or leave it,” “God loves America most,” "We are an exceptional nation," etc. Thus change is unnecessary. From the progressive left comes the idea that there is much unfilled promise in our era, thus the need to change things for the better by advancing a progressive political agenda. Conservatives want to conserve---traditional marriage, white supremacy, current economic system---or go backward---get rid of social security, women in the labor force, minimum wage, contraception, labor unions, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. Liberals want to liberate and free people from undue burdens like lack of health care and affordable education, minimum wage jobs, unwanted pregnancies, racial prejudice, etc. Obviously this is all more complicated than this but that’s the general idea.]

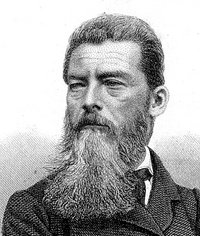

Feuerbach

The other main influence on Marx was Ludwig Feuerbach. Rather than agreeing with Hegel that geist or god realizes itself (himself) throughout history, humans create religion as an idealized version of life in this world. [This world is so bad that people imagine a perfect world.] Here Feuerbach uses another idea of Hegel’s—the idea of alienation in which subjects confront objects unknown and alien from themselves. Feuerbach argued that people become alienated when “they project their own human potential into theological fantasies and undervalue their actual lives.” Feuerbach argued that metaphysics and theology are expressions of our emotions disguised as claims about reality. “So he saw religion as symptom of human alienation, from which we must free ourselves by realizing our destiny in this world.”

All this led Marx to conclude that Hegel was right to be concerned about truth and progress in history, but wrong to think the natural, historical world was a manifestation of the development of spirit or mind. Instead Marx argued that thought and mind are manifestations of the natural world, of material conditions. (Hence the idea that Marx turned Hegel upside down.) The driving force of social change are not ideas about gods or cosmic spirits, but economic conditions. And alienation is not primarily religious but social and economic. In a capitalist system we are alienated from our labor because we don’t work for ourselves, but for others who own the means of production and the products of our labor. Capitalists try to maximize profit, exploiting their workers by paying them the minimum needed for their survival.

The Materialist Theory of History – Marx was an atheist and a materialist. He thought of himself as a social scientist that had discovered a scientific way to study “economic history of human society.” He was looking for general socio-economic laws that applied to human history both synchronically and diachronically. Here is what he argued.

At any given time, synchronically, economics determines ideology. The rich and powerful defend capitalism because it serves their interests. Their rhetoric regarding freedom of enterprise, trade, and markets expresses the self-interest of those who possess land and money. The rest are left “free to starve,” if the labor markets won’t give them jobs. [Or they can be incarcerated or killed in foreign wars that serve their capitalistic interests.] Marx claims that social, legal, and political power were in the hands of capitalists, especially the very wealthy, although government has tried to regulate the excesses of capitalism by banning child labor, minimum wage laws, health and safety laws, environmental protection, some health care and retirement benefits, etc. [Marx would not be surprised to find that in a rich country like America today, the capitalists and financiers try to influence, if not control, any government attempts to reign in their excess profits or contributions to climate and other environmental degradation. The government becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of business.]

Looking across time, diachronically, Marx recognized that economic and technological development will result in social, political and ideological change. Consider how agriculture, slavery, feudalism, or the industrial revolution transformed social and political life. Marx’s salient insight is that a materialist, economic theory of history explains these transformations. A brief summary of this insight can be seen in this passage:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness …

The economic base of a society provides the foundation of one’s social life, and it conditions that social life to a great extent. To understand this would be pay attention the distinctions Marx draws between:

a) Material powers of production: natural resources including land, climate, plants, animals, minerals; technology such as tools, machinery, communication systems; and human resources like labor power and skills.

b) Economic Structure: the organizational structure of work, division of labor, authority in the workplace, legal power of ownership, systems of rewards and payments, legal concepts of property, economic concepts like money, capital, and wages.

c) Ideological Superstructure: social beliefs, morality, laws, politics, religion, and philosophy.

It is not exactly clear what Marx meant by economics being the basis or foundation of social life. Is that foundation a, or a and b? Does a determine b and therefore c? Or does b determine c alone? Or do a and b determine c? [I think the argument as a whole works even if some of the details aren’t entirely clear.] The key question is how much conditioning or influencing or determining did Marx believe that economics had on ideology. Surely we have to eat before we can act or think but it doesn’t seem to follow that this determines everything we do or think. Still the economic structure of a society sets limits on and influences how people think.

[For example, the economic structure determines how you can earn your bread in a society, and thus the way most people act a large part of the time. But consider how earning your money selling cigarettes, crude oil, real estate, alcohol, or assault weapons significantly influences how you think about those things. Or consider how growing up in a sub-culture with few economic opportunities strongly influences how you think about occupations like small time drug dealer, prostitute, professional boxing, as well as about law enforcement, courts, laws, foreign wars, etc. Consider the vastly different political views of those in different socio-economic classes. You can probably think of all sorts of other examples of this connection between economics and ideology.]

While none of this implies hard determinism, Marx thought that capitalism would become gradually more unstable, class struggle would increase, with the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer.

[These themes were in large part the subject of the economist Thomas Piketty’s recent worldwide best-seller.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Piketty is arguably the world's foremost expert on income and wealth inequality. His "central thesis is that when the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of economic growth (g) over the long term, the result is concentration of wealth, and this unequal distribution of wealth causes social and economic instability. Piketty proposes a global system of progressive wealth taxes to help reduce inequality and avoid the vast majority of wealth coming under the control of a tiny minority."1 Consider how your own reaction to such claims is largely determined by your own socio-economic background. I have written about these issues here, here, here and here.]

The extent to which Marx’s predictions have come true is open to debate. On the one hand, capitalism more or less reins in first world countries, although technically we have mixed economies, on the other hand the strengthening of the social safety net in first world countries may have prevented the kind of upheaval that Marx envisioned. Moreover 3rd world countries may be the proletariat for 1st world countries today.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_...

Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 14 – Marx – Part 1

Marx: The Economic Basis of Society

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature. )

We are interested in Marxist theory, not in the various ways it may have been implemented. [Think of the parallel with Christianity. If you are a Christian and someone says "Christians conducted the Crusades and Inquisition, they may have collaborated with the Nazis and protected pedophile priests," you answer that none of that is Christian behavior. A Marxist can say the same about Stalin or Mao or North Korea.] Who was Karl Marx (1818 – 1883)? “Marx was the greatest critical theorist of the Industrial Revolution and nineteenth-century capitalism … Although hostile to religion, Marx inherited an ideal of human equality and freedom from Christianity, and he shared the Enlightenment hope that scientific method could diagnose and resolve the problems of human society … Behind his … theorizing was a prophetic, quasi-religious zeal to show the way toward a secular form of salvation.”

Hegel

Marx studied at the University of Berlin in the mid nineteenth-century at a time and place when G.W.F. Hegel’s thought was dominant. Hegel believed in a progressive human history where Geist—mind, spirit or god—develops throughout history. All human history is “the progressive self-realization of Geist.” In other words human social life evolves in a progressive direction as more adequate ideas of reality slowly emerging leading to greater consciousness, self-awareness and freedom. [Hegel’s philosophy is notoriously complex and abstruse. But the process in large part takes place as a dialectic between ideas. A thesis is offered, its antithesis advanced, and a synthesis emerges.] Hegel believed that mental and cultural development eventually reaches a state of absolute knowledge. Right Hegelians believed that the 19th Prussian state had reached a near perfect state of development; left Hegelians believed it had not, that the society was far from ideal and it was up to people to make it better.

[Consider the parallels with politics in the USA today. From the conservative right we hear that “the USA is the greatest nation ever,” “American love it or leave it,” “God loves America most,” "We are an exceptional nation," etc. Thus change is unnecessary. From the progressive left comes the idea that there is much unfilled promise in our era, thus the need to change things for the better by advancing a progressive political agenda. Conservatives want to conserve---traditional marriage, white supremacy, current economic system---or go backward---get rid of social security, women in the labor force, minimum wage, contraception, labor unions, Medicare, Medicaid, etc. Liberals want to liberate and free people from undue burdens like lack of health care and affordable education, minimum wage jobs, unwanted pregnancies, racial prejudice, etc. Obviously this is all more complicated than this but that’s the general idea.]

Feuerbach

The other main influence on Marx was Ludwig Feuerbach. Rather than agreeing with Hegel that geist or god realizes itself (himself) throughout history, humans create religion as an idealized version of life in this world. [This world is so bad that people imagine a perfect world.] Here Feuerbach uses another idea of Hegel’s—the idea of alienation in which subjects confront objects unknown and alien from themselves. Feuerbach argued that people become alienated when “they project their own human potential into theological fantasies and undervalue their actual lives.” Feuerbach argued that metaphysics and theology are expressions of our emotions disguised as claims about reality. “So he saw religion as symptom of human alienation, from which we must free ourselves by realizing our destiny in this world.”

All this led Marx to conclude that Hegel was right to be concerned about truth and progress in history, but wrong to think the natural, historical world was a manifestation of the development of spirit or mind. Instead Marx argued that thought and mind are manifestations of the natural world, of material conditions. (Hence the idea that Marx turned Hegel upside down.) The driving force of social change are not ideas about gods or cosmic spirits, but economic conditions. And alienation is not primarily religious but social and economic. In a capitalist system we are alienated from our labor because we don’t work for ourselves, but for others who own the means of production and the products of our labor. Capitalists try to maximize profit, exploiting their workers by paying them the minimum needed for their survival.

The Materialist Theory of History – Marx was an atheist and a materialist. He thought of himself as a social scientist that had discovered a scientific way to study “economic history of human society.” He was looking for general socio-economic laws that applied to human history both synchronically and diachronically. Here is what he argued.

At any given time, synchronically, economics determines ideology. The rich and powerful defend capitalism because it serves their interests. Their rhetoric regarding freedom of enterprise, trade, and markets expresses the self-interest of those who possess land and money. The rest are left “free to starve,” if the labor markets won’t give them jobs. [Or they can be incarcerated or killed in foreign wars that serve their capitalistic interests.] Marx claims that social, legal, and political power were in the hands of capitalists, especially the very wealthy, although government has tried to regulate the excesses of capitalism by banning child labor, minimum wage laws, health and safety laws, environmental protection, some health care and retirement benefits, etc. [Marx would not be surprised to find that in a rich country like America today, the capitalists and financiers try to influence, if not control, any government attempts to reign in their excess profits or contributions to climate and other environmental degradation. The government becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of business.]

Looking across time, diachronically, Marx recognized that economic and technological development will result in social, political and ideological change. Consider how agriculture, slavery, feudalism, or the industrial revolution transformed social and political life. Marx’s salient insight is that a materialist, economic theory of history explains these transformations. A brief summary of this insight can be seen in this passage:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness …

The economic base of a society provides the foundation of one’s social life, and it conditions that social life to a great extent. To understand this would be pay attention the distinctions Marx draws between:

a) Material powers of production: natural resources including land, climate, plants, animals, minerals; technology such as tools, machinery, communication systems; and human resources like labor power and skills.

b) Economic Structure: the organizational structure of work, division of labor, authority in the workplace, legal power of ownership, systems of rewards and payments, legal concepts of property, economic concepts like money, capital, and wages.

c) Ideological Superstructure: social beliefs, morality, laws, politics, religion, and philosophy.

It is not exactly clear what Marx meant by economics being the basis or foundation of social life. Is that foundation a, or a and b? Does a determine b and therefore c? Or does b determine c alone? Or do a and b determine c? [I think the argument as a whole works even if some of the details aren’t entirely clear.] The key question is how much conditioning or influencing or determining did Marx believe that economics had on ideology. Surely we have to eat before we can act or think but it doesn’t seem to follow that this determines everything we do or think. Still the economic structure of a society sets limits on and influences how people think.

[For example, the economic structure determines how you can earn your bread in a society, and thus the way most people act a large part of the time. But consider how earning your money selling cigarettes, crude oil, real estate, alcohol, or assault weapons significantly influences how you think about those things. Or consider how growing up in a sub-culture with few economic opportunities strongly influences how you think about occupations like small time drug dealer, prostitute, professional boxing, as well as about law enforcement, courts, laws, foreign wars, etc. Consider the vastly different political views of those in different socio-economic classes. You can probably think of all sorts of other examples of this connection between economics and ideology.]

While none of this implies hard determinism, Marx thought that capitalism would become gradually more unstable, class struggle would increase, with the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer.

[These themes were in large part the subject of the economist Thomas Piketty’s recent worldwide best-seller.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Piketty is arguably the world's foremost expert on income and wealth inequality. His "central thesis is that when the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of economic growth (g) over the long term, the result is concentration of wealth, and this unequal distribution of wealth causes social and economic instability. Piketty proposes a global system of progressive wealth taxes to help reduce inequality and avoid the vast majority of wealth coming under the control of a tiny minority."1 Consider how your own reaction to such claims is largely determined by your own socio-economic background. I have written about these issues here, here, here and here.]

The extent to which Marx’s predictions have come true is open to debate. On the one hand, capitalism more or less reins in first world countries, although technically we have mixed economies, on the other hand the strengthening of the social safety net in first world countries may have prevented the kind of upheaval that Marx envisioned. Moreover 3rd world countries may be the proletariat for 1st world countries today.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_...

November 12, 2014

On Human Nature and Its Future

I am teaching a course on the philosophy of human nature at a local university. Here are a few quotes on the topic.

[Humans] will become better when you show [them] what [they are] like. ~ Anton Chekhov

We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars. ~ Oscar Wilde

This may be the curse of the human race. Not that we are so different from one another, but that we are so alike. ~ Salman Rushdie

[image error]Share