Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 17 – Freud – Part 1

Freud: The Unconscious Basis of Mind

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes of the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature. )

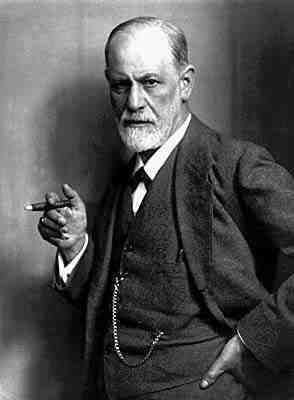

“Freud’s psychoanalytic approach to the mind revolutionized our understanding of human nature in the first half of the twentieth-century.” Freud (1856 – 1939) grew up in Vienna where he lived until the last year of his life. He was an outstanding student with a broad range of academic interests, he attended the University of Vienna medical school, and worked as a physician before setting up a private practice in nervous disorders at the age of thirty. He continued that work for the rest of his life.

In the first phase of his intellectual career “he put forth some original hypotheses about the nature of neurotic problems, and began to develop his distinctive method of treatment, which came to be known as psychoanalysis.” From his early experiences conducted with middle-class Viennese woman, Freud hypothesized that emotional symptoms had their roots in a long-forgotten emotional trauma that needed to be recalled so that the emotions associated with it could be discharged. [This mechanical model is itself problematic. Do humans build up pressure like machines? Is there a better model to describe them?] This was the beginning of the idea of psychoanalysis. Freud also found that in many cases that patients reported their trauma originated in sexual abuse—although he was uncertain how often these reports were reliable. Freud postulated that psychology had a physical basis in the brain, but neurophysiology was not developed enough at the time to confirm this.

Around the turn of the century he also began to formulate theories about sexual development and the interpretation of dreams. Ideas common to our lexicon would subsequently spring up—resistance, repression, and transference. Such ideas were applied to everyone’s mental life, giving birth to a new psychological theory. Starting around 1920, Freud changed his theories introducing the death and life instincts, as well as his division of the mind into the id, ego, and superego. In his later years he wrote his most philosophical works. The Future of an Illusion regarded religion “as a system of false beliefs whose deep infantile root in our minds can be explained psychoanalytically.” While Civilization and Its Discontents “discussed the alleged conflict between individual drives and the morals of civilized society.”

The Future of an Illusion

The Future of an Illusion

Civilization and Its Discontents

Civilization and Its Discontents

Freud escaped Austria right before the start of World War II and died a year later in London. [Freud suffered terribly from cancer of the jaw in the final months of his life. On September 21 and 22 his doctor administered the doses of morphine, as he had promised and Freud requested, that resulted in Freud's death on 23 September 1939.]

Metaphysical Background: Neuroscience, Determinism, and Materialism – Freud began his career as a physiologist who always tried to explain all phenomena scientifically. He had no use for theology or transcendent metaphysics, believing instead that the human condition could be improved by the application of science and reason. Living post-Darwin, Freud recognized that human beings are animals related to all living things, and he believed that both mental and physical events are determined by physical causes. This meant that Freud was a materialist regarding mind—as almost all philosophers and scientists are today—mental states, including unconscious states, are dependent upon brain states. He left the project of discovering the relationship of mental states and the brain to future scientists, a project that has developed enormously since his time.

Theory of Human Nature: Mental Determinism, The Unconscious, Drives, and Child Development – The first major idea in Freud’s theory of human nature is the application of determinism to psychology. This would seem to imply that humans do not possess free will, but Freud was ambivalent about that philosophical question. On the one hand he thought the contents of consciousness are determined by individual, psychological and biological drives, while on the other hand he believed that we sometimes make rational decisions and judgments. (This is similar to Marx’s view, although Marx held that the causes of the contents of our consciousness were primarily social and economic.)

The second key idea in Freud’s theorizing is the postulation of the unconscious. For Freud there are not only preconscious states, those we aren’t continually conscious of but can recall if needed, but unconscious states that can’t ordinarily become conscious. Our minds contain elements of which we have no awareness, but which exert influence on us nonetheless. Some elements of the unconscious may have originally been conscious, say a traumatic event in childhood, but were subsequently repressed—a process of pushing ideas into the unconscious. [Is this is done consciously or unconsciously?] He also advanced his famous three-part division of the structure of the mind: 1) id, instinctual drives that seek immediate satisfaction according to the pleasure principle; 2) ego, conscious mental states governed by a reality principle; and 3) superego, the conscience, which confronts the ego with moral rules or feeling of guilt and anxiety. The ego tries to reconcile the conflicting demands of the id—I want candy—with the superego—you shouldn’t steal candy.

The third main idea in Freud is his focus on drives or instincts. These drives manifest themselves in multiple ways. Freud, following the mechanical models of his day, felt these drives need to be discharged or pressure builds up. [Again this is at best a model, and probably not a good one.] Freud emphasized the sexual drive to a much greater extent than any previous thinker, but other important drives include the drive for self-preservation and other life-enhancing drives (eros), as well as self-destructive drives for sadism, aggression or death instinct (Thanatos). However Freud acknowledged these ideas were preliminary.

The fourth major aspect of Freud’s theorizing was his offering of a developmental account of human personalities. He places particular emphasis on the crucial importance of childhood for future psychological development. [Be nice to your children.] In fact he didn’t believe you could understand any adult without knowing about facets of their childhood, including various sexual stages of development. And while Freud has been criticized for his focus on the Oedipus complex, most likely he was making the point that the love between parents and children foreshadowed adult love. However if individuals don’t develop properly then psychoanalysis may be the only way one can reverse the damage of childhood.

Diagnosis: Mental Harmony, Repression, and Neurosis – “Like Plato, Freud held that individual well-being, happiness, or mental harmony depends on a harmonious relationship between various parts of the mind, and between the whole person and society.” [This might explain why some countries---most notably, New Zealand, Switzerland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Finland, and Denmark---do so much better than other countries on the Social Progress Index.] The ego seeks to satisfy its demands, but if there is a dearth of opportunities to do this, pain and frustration ensue. Yet even in the best of situations there is obsession, neuroticism, and other mental illness.

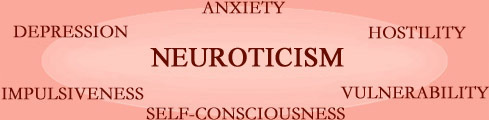

Freud believed that repression was a primary cause of neuroticism. If someone experiences drives or desires (or beliefs) that conflict with standards or norms they are supposed to adhere to, then such feelings are often repressed. Repression is a defense mechanism used to avoid mental conflict. But repression ultimately doesn’t work, for the desires or drives remain in the unconscious exerting their influence. They may lead to irrational behaviors that we cannot control. Furthermore much of the blame for neuroses Freud attributes to the social world. Parents and other parts of culture may make unrealistic demands upon people. In fact Freud speculated that entire societies can be described as neurotic. While the exact meaning of this claim is ambiguous, clearly some societies do better at providing the conditions in which individuals can flourish.