John G. Messerly's Blog, page 127

December 29, 2014

Death and the Meaning of Life

Death causes many people to doubt life’s meaning. It isn’t surprising that the meaninglessness of life consumes Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, or that death figures prominently in the world’s literature about the meaning of life. Consider these haunting lines from James Baldwin:

Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.

Something binds the topics of death and meaning. The thought of oblivion arouses even the non-philosophical among us. What is the relationship between death and meaning?Death is variously said to:

render life meaningless;

detract from life’s meaning;

add to life’s meaning;

render life meaningful.

Death has always been inevitable, but the idea that science will eventually conquer death has taken root—achieved through some combination of future technologies like nanotechnology, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and robotics. Some think the possibility of technological immortality renders human life meaningless, others that life can only attain its full meaning if death is overcome.

But whatever view one takes about the relationship between death and meaning, the two are joined. If we had three arms or six fingers, our analysis of the meaning of life wouldn’t change; but if we didn’t die our analysis would be vastly different. If our concerns with annihilation vanished, a good part of what seems to undermine meaning would disappear. To understand the issue of the meaning of life, we must think about death. Pascal’s words echo across the centuries:

Imagine a number of men in chains, all under sentence of death, some of whom are each day butchered in the sight of the others; those remaining see their own condition in that of their fellows, and looking at each other with grief and despair await their turn. This is an image of the human condition.

Can we find meaning in this picture?

___________________________________________________________________________

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage, 1992).

December 28, 2014

Do We Ask About Meaning Because We Are Sick, Decadent, or Unhappy?

Do We Ask Because We’re Sick? – Freud may have been right when he claimed: “The moment a [person] questions the meaning of life, [they are] sick …” No doubt the question of life’s meaning arises more often when things go badly than when they go well, but the question can arise anytime. Even if you ask the question continually, thinking about an important question is not necessarily detrimental to mental health. You might enjoy constantly thinking about the question as others enjoy their daily walk. Despite Freud’s claims , we will assume that he is wrong—asking questions about the meaning of life does not reveal mentally illness. On the contrary, posing deep questions may be a marker of psychological health, the truest expression of humanity.

Do We Ask Because We’re Decadent? – Only those whose basic needs are met have time for philosophical contemplation. So isn’t it decadent for the well-off to pose these questions, especially when many others barely survive? Isn’t it disingenuous when the well-fed muse over the worthiness of their lives? I don’t think so. Perhaps the people posing the questions are decadent, but that doesn’t mean the questions themselves are trivial. A desire for truth, not self-indulgence, may motivate questions. And good might come from thinking about non-trivial questions—maybe the contemplative will become kinder or more generous as a result. To search for meaning is not corrupt.

Do We Ask Because We’re Unhappy? – If we were happy, would we still wonder about the meaning of life? And if not, does that mean that happiness is the meaning of life? Aristotle thought that happiness was the goal of life, although it is not clear that he thought the happy life and the meaningful one were coextensive. We generally think less about meaning when we are happy, but even then questions about meaning arise. We may, for example, be disturbed that our happiness will not last. And most philosophers do not think that happiness and meaning are synonymous, even though both are goods. Here is why.

Meaning and Happiness – It is easy to imagine a happy life that isn’t meaningful. You could be happy connected to a futuristic happiness machine, but we would hesitate to call such lives meaningful. Alternatively, one’s life might be meaningful but unhappy—some people are unhappy when doing their duty. Maybe then the moral life is the meaningful one. But that does not seem right either, inasmuch as lives can be meaningful without reference to morality. I may find meaning collecting coins or rooting for a sports team, but neither are moral actions. Perhaps then lives are more meaningful if they are also happy or moral. Perhaps. But this does not mean that happiness, morality and meaning are the same. Meaning seems distinct from both happiness and morality. Meaning is sui generis.

________________________________________________________________________

Sigmund Freud, The Letters of Sigmund Freud (New York: Basic Books, 1960), 436.

Thaddeus Metz, “Happiness and Meaningfulness: Some Key Differences,” in Philosophy and Happiness, ed. Lisa Bortolotti (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

December 27, 2014

Emotions and the Meaning of Life

Do emotions influence your view of the meaning of life more than rational considerations?If so then our thinking about meaning isn’t neutral but thoroughly infused with prejudices. In fact it is probably impossible to separate our reason and emotion from each other, and recent research suggests that emotions play an important part in our reasoning. Our philosophy may simply reflect our personality.

Yet there is evidence that reason and emotion lead to different results when applied to philosophical issues. For instance, consider the “trolley problem,” where a runaway train approaches a fork in the track with one person tied to the track on one side, and five persons tied to a track on the other. People are more likely to recommend flipping a switch diverting a train to kill one person rather than five, than they are to recommend pushing a single individual in the train’s path to divert it—even though the outcome of the actions is the same. The typical explanation of this discrepancy is that flipping the switch is a more neutral action that elicits a cognitive response whereas pushing the person elicits a more emotional response.

We don’t know how or if our brain fuses its rational and emotional components to make philosophical decisions. It could be that reasoning leads to conclusions about meaning, but that our emotions resist them; or it could be that a unitary brain decides. We just don’t know. (It is doubtful whether talk of rational and emotional brains makes sense.) Given this uncertainty as to the role reasons, feelings, and attitudes play in the evaluative process, as well as whether our models adequately describe brains, we should be skeptical of our philosophical conclusions. If we really want to know what is true, we should continually reevaluate all of our tentative conclusions. We should remain fallibilists.

________________________________________________________________________

Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (New York: Harper Perennial, 1995).

Joshua D. Greene, “The Secret Joke of Kant’s soul,” in Moral Psychology, Vol. 3: The Neuroscience of Morality, ed. W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008).

December 26, 2014

Meaning of Life Answers and Other Philosophical Views

A recent post provided a taxonomy of the answers to the meaning of life question. It may be helpful if we note at the outset how answers to meaning of life questions are extensions of other views in philosophy. Thus:

Negative answers – These are extensions of metaphysical, epistemological, and moral nihilism. If one argues that nothing ultimately matters—not reality, knowledge or morality—then one is probably committed to nihilism regarding the meaning of life. This view can be further divided between those who positively affirm that life is meaningless, and those who begrudgingly accept life’s meaninglessness.

Agnostic answers – These are extensions of metaphysical, epistemological, and moral skepticism. If one is skeptical of our ability to ask or answer pertinent questions in metaphysics, epistemology, or ethics, then one is likely to be skeptical of our ability to ask or answer questions about the meaning of life.

Positive answers (theistic) – These are extensions of metaphysical, epistemological, and moral supernaturalism. If one holds there to be a supernatural basis for metaphysical, epistemological, and moral truth, then one is probably committed to a supernatural basis for meaning.

Positive answers (non-theistic) – These are extensions of metaphysical, epistemological, and moral naturalism. If one holds there to be only natural metaphysical, epistemological, and moral truth, then one is surely committed to a naturalistic view of meaning. This view can be further subdivided between objectivists, who think you primarily discover value and meaning in the natural world; and subjectivists, who think you primarily create your own value and meaning in an otherwise meaningless cosmos.

This connection between metaphysical, epistemological, ethical issues, and questions of meaning should be self-evident. It is easy to see that the question “is meaning objective or subjective?” is similar to the questions: “is reality objective or subjective?” or “is truth subjective or objective?” or “is value subjective or objective?” Again the question “what is meaningful?” is similar to the questions “what is real?” or “what is true?” or “what is good?” Thus we find striking parallels between answers to the question of meaning, and answers to other basic philosophical questions.

Such parallels suggest that answers to the meaning of life question must await answers to these other philosophical issues. Unless we know which metaphysical, epistemological or ethical view is correct, how can we know which view of the meaning of life is best? So the problem with choosing between our various answers—nihilism, skepticism, supernaturalism, and naturalism—is that they are parts of differing philosophies of life or world views. And if our view of the meaning of life follows from our world view, then our question becomes: how do we choose between world views? This suggests that answers to the meaning of life question depend on our choosing a world view. In that case, we could dispense with the meaning of life question and investigate the philosophical world views upon which our view of meaning rests. Then, after determining which world view is best, our view of the meaning of life would inexorably follow.

But we should not draw this conclusion too hastily. It is not certain that our view of meaning follows from our world view. Furthermore, the process may work in reverse; perhaps our view of meaning comes first, and then leads us to our world view. Yes, it will be difficult to answer questions of meaning first, but it is difficult to answer other philosophical questions as well. Our question may be no harder to answer than the other questions to which philosophers devote effort. If investigations of other philosophical questions are worthwhile, then so is this investigation. In fact, an analysis of the question of meaning may tell us something important about what is real, what we can know, and what we should value. Thus there is no a priori reason to postpone our pursuit.

December 25, 2014

Depression: Whose Fault Is It?

I was recently involved in a discussion about someone who had committed suicide. I don’t know the details but evidently the victim was a successful, mid-career man, suffering from depression. A major contributing factor was job stress. Here is how the dialogue went:

A Tough Guy (TG)- The guy was stupid and weak-minded. He needed to master his thoughts. If his job was stressful, he should have gotten another one. If his thoughts were troubling, he should changed them. If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.

A Compassionate Guy (CG) – Depression can strike anyone, it is a disease. If you experience enough stress you can have a mental breakdown. Just spend a few hours in a war zone or a few years in a stressful job and you can find out for yourself. If possible you should avoid bad situations, but you can’t always do that. Depressed persons need compassion and professional help.

TG – If you really care about someone tell them not to put themselves in situations where they might get hurt.

CG – Sure. But if they’re already suffering from mental illness it’s too late. By that time they are then in a situation which is beyond their control. At that point free will, if it exists, can’t intervene.

A Former Depressed Guy (FS) – When you are suffering from depression you can’t think rationally, just like when you are physically ill you can’t perform certain physical tasks. Friends helped me get help before I had my own breakdown, but many aren’t that lucky.

A Social Scientist (SS) – It’s problematic to insinuate that the fault with depression or suicide lies within the person. One million people decide to take their life every year, that’s 1.5% of all deaths worldwide. The problem is the system. Many want to get out of the kitchen, but they can’t because the kitchen is the whole world. So we should destroy the kitchen, and rebuild it so that it doesn’t burn us any more.

An Economist (E) – It’s clear that the developed world faces issues related to stress—largely driven by capitalistic modes of production which have reduced the value of individual human experience. Here is an article about South Korea that makes the point.

TG – Don’t blame the world; blame yourself. You decided to become stressed. So change yourself.

SS – We need societal structural change which leads to individual change, which in turn leads to societal change. We need a society based on a new social contract that meets people’s biological and psychological needs. A world where people aren’t forced into competitive environments. A cooperative society based more on social capital than economic capital. A society with work that is stable and psychologically fulfilling.

TG – Until then if you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.

CG – That’s what this talented man did. He followed your advice. That’s not an indictment of him, even by your own standards. It’s an indictment of the world. We need to rethink the world.

December 24, 2014

A Taxonomy of Answers to the Question of the Meaning of Life

Answers to the question of the meaning of life fall into one of three categories:

Negative (nihilistic) answers—life is meaningless;

Affirmation—it is good that life is meaningless;

Acceptance—it is not good that life is meaningless;

Agnostic (skeptical) answers—we don’t know if life is meaningful;

The question is unintelligible;

The question is intelligible, but we don’t know if we can answer it;

Positive answers—life is meaningful;

Supernatural (theistic) answers—meaning from transcendent gods;

Natural (non-theistic) answers—meaning created/discovered in natural world;

a) meaning is objective—discovered or found by individuals;

b) meaning is subjective—created or invented by individuals.

Think of these responses on a continuum:

Agnosticism

/ \

Unanswerable Unintelligible

____________________________________________________________________

Meaningless Somewhat Meaningful Meaningful

/ \ / \

Affirm Accept Natural Supernatural

/ \

Objective Subjective

Agnosticism is placed above the continuum because it is a meta-view. Agnostics are not halfway between the two ends of the continuum; they do not think life is partly meaningful and partly meaningless. Instead they argue that the issue cannot be resolved either because the question makes no sense or, if it does make sense, cannot be answered, or, if it can be answered, we have no way of knowing whether that answer is correct.

Note that these divisions are not exclusive or exhaustive but guidelines to the plethora of views. Many philosophers’ views do not fall clearly within a given label. For example, agnostics may hold that the question is basically unintelligible, yet claim that a few positive things can be said, or that the question is mostly, but not completely, unanswerable. And naturalists typically hold that there are both objective and subjective components to meaning.

This latter distinction between objective and subjective naturalists is hard to draw. If philosophers emphasize subjective values that are dependent on individuals as the source of meaning, we categorize them as subjective naturalists. If they emphasize objective values that are independent of people as the source of meaning, we categorize them as objective naturalists. But many thinkers blur this line, arguing that we both create meaning, and discover it in objectively good things. The distinction between the two is that those I call objectivists defend the idea of objective value whereas the subjectivists do not. At any rate, categorizing responses helps situate particular views within a broader context, although the specifics of various views must speak for themselves.

December 23, 2014

Science Explains Religion

(This is a reprint of a previous post. I thought it appropo given the thousands of comments to my recent article that appeared at Salon: “Religion’s Smart-People Problem.”)

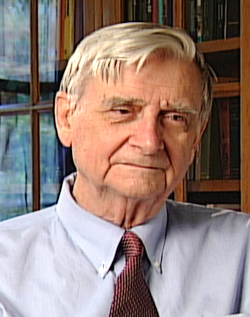

Edward O. Wilson (1929 – ) is a biologist, theorist, naturalist, and two-time Pulitzer Prize winning author for general non-fiction. He is the father of sociobiology and as of 2007 was the Pellegrino University Research Professor in Entomology in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. He is also a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism, and one of the world’s most famous living scientists.

In his Pulitzer Prize winning book On Human Nature (1978), Wilson extended sociobiology, the study of the biological basis of human social behavior, into the realms of human sexuality, aggression, morality, and religion. Deploying sociobiology to dissect religious myths and practices, led him to affirm: “The predisposition to religious belief is the most complex and powerful force in the human mind and in all probability an ineradicable part of human nature.”[i]Religion is a universal of social behavior, recognizable in every society in history and prehistory, and skeptical dreams that religion will vanish are futile. Scientific humanists, consisting mostly of scholars and scientists, organize into small groups which try to discredit superstition and fundamentalism but “Their crisply logical salvos, endorsed by whole arrogances of Nobel Laureates, pass like steel-jacketed bullets through fog. The humanists are vastly outnumbered by true believers … Men, it appears, would rather believe than know. They would rather have the void as purpose … than be void of purpose.”[ii]

Other scholars have tried to compartmentalize science and religion—one reads the book of nature, the other the book of scripture. However, with the advance of science, the gods are now to be found below sub-atomic particles or beyond the farthest stars. This situation has led to process theology where the gods emerge alongside molecules, organisms and mind, but, as Wilson points out, this is a long way from ancient religion. Elementary religion sought the supernatural for mundane rewards like long life, land, food, avoiding disasters and conquering enemies; whereas advanced religions make more grandiose promises. This is what we would expect after a Darwinian competition between more advanced religions, with competition between sects for adherents who promotes the religion’s survival. This leads to the notorious hostility between religions where, “The conqueror’s religion becomes a sword, that of the conquered a shield.”[iii]

The clash between science and religion will continue as science dismantles the ancient myths that gave religion its power. Religion can always maintain that gods are the source of the universe or defend esoteric arguments, but Wilson doubts the strategy will ultimately succeed, due to the power of science.

It [science] presents the human mind with an alternative mythology that until now has always, point for point in zones of conflict, defeated traditional religion … the final decisive edge enjoyed by scientific naturalism will come from its capacity to explain traditional religion, its chief competitor, as a wholly material phenomenon. Theology is not likely to survive as an independent intellectual discipline.[iv]

Still, religion will endure because it possesses a primal power that science lacks. Science may explain religion, but it has no apparent place for the immortality and objective meaning that people crave and religion claims to provide. To fully address this situation, humanity needs a way to divert the power and appeal of religion belief into the service of scientific rationality.

However, this new naturalism leads to a series of dilemmas. The first is that our species has no “purpose beyond the imperatives created by its genetic history.”[v]In other words, we have no pre-arranged destiny. This suggests the difficulty human society will have in organizing its energy toward goals without new myths and new moralities. This leads to a second dilemma “which is the choice that must be made among the ethical premises inherent in man’s biological nature.”[vi] Ethical tendencies are hard-wired, so how do we choose between them? A possible resolution to the dilemmas combines the powerful appeal of religion and mythology with scientific knowledge. One reason to do this is that science provides a firmer base for our mythological desires because of:

Its repeated triumphs in explaining and controlling the physical world; its self-correcting nature open to all competent to devise and conduct tests; its readiness to examine all subjects sacred and profane; and now the possibility of explaining traditional religion by the mechanistic models of evolutionary biology.[vii]

When the latter has been achieved religion will be explained as a product of evolution, and its power as an external source of morality will wane. This will leave us with the evolutionary epic, and an understanding that life, mind and universe are all obedient to the same physical laws. “What I am suggesting … is that the evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have.”[viii] (Myth here means grand narrative.) None of this implies that religion will be fully eradicated, for rationality and progressive evolutionism hold little affection for most, and the tendency for religious belief is hard-wired into the brain by evolution. Still, the pull of knowledge is strong—technologically skilled people and societies have tremendous advantages and they tend to win out in the struggle for existence.

Our burgeoning knowledge of human nature will lead in time to a third dilemma: should we change our nature? Wilson leaves the question open, counseling us to remain hopeful. The true Promethean spirit of science means to liberate man by giving him knowledge and some measure of dominion over the physical environment. But at another level, and in a new age, it also constructs the mythology of scientific materialism, guided by the corrective devices of the scientific method, addressed with precise and deliberately affective appeal to the deepest needs of human nature, and kept strong by the blind hopes that the journey on which we are now embarked will be farther and better than the one just completed.[ix]

______________________________________________________________________

[i] Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) 169.

[ii] Wilson, On Human Nature, 170-71.

[iii] Wilson, On Human Nature, 175.

[iv] Wilson, On Human Nature, 192.

[v] Wilson, On Human Nature, 2.

[vi] Wilson, On Human Nature 4-5.

[vii] Wilson, On Human Nature, 201.

[viii] Wilson, On Human Nature, 201.

[ix] Wilson, On Human Nature, 209.

Share

ShareDecember 22, 2014

Einstein and Darwin Were Not Believers

My article, “Religion’s Smart People Problem,” appeared in Salon yesterday. As of today it is still the most read piece, generating more than 1700 comments on Salon and numerous others on my blog. I thank the readers for their interest. Here are a few more points about a big topic.

Does Religion Have a Smart-People Problem?

I do think that religion has a smart-people problem, as the religious themselves sometimes sense. Often I have heard defensive believers say things like: “Well, Einstein believed in God,” or “Darwin converted on his deathbed.” One problem is that both claims are false. Einstein’s religious views have been studied in detail and he was a pantheist or agnostic. The Darwin deathbed conversion story is an urban Christian legend discredited even on creationist websites. Although Darwin had originally studied for the clergy, he was an agnostic or quiet atheist by the end of his life.

The other problem is that appeals by believers to the beliefs of scientific luminaries seems desperate. It’s as if you’re saying: “Maybe I can’t give good reasons for my beliefs but some smart people believe them so they can’t be stupid.” But if your beliefs are true, what difference does it make whether Einstein or Darwin believes them? If you are confident of your beliefs, why invoke the name of some great scientists? You likely invoke famous scientists to give legitimacy to beliefs that you worry may be indefensible. But remember, a proposition is true of false independent of what anyone believes. Apollo is either real or he is not.

As I said in my Salon piece, there are smart, educated people who have religious beliefs. Yet it is a fact that such belief decreases with education. This fact doesn’t make your religious beliefs false, but it should cause you to wonder what would happen to your beliefs if you had a better scientific or philosophical education. Your beliefs might remain unchanged, but the evidence suggests otherwise. That is why religious indoctrination tries to shield the faithful from various contrary ideas.

The issue is similar if you consider your place of birth. If you were born in the United States you are probably not a Muslim, if you were born in Iran there is a good chance you are. If you were born in India you are probably not a Christian, if you were born in the United States there is a good chance you are. You might believe that your religious beliefs would be the same had you been born somewhere else, but the evidence suggests otherwise.

This indicates that you have been conditioned to hold religious beliefs by, among others things, your education and place of birth. Once conditioned you hold onto those beliefs with tenacity because, as the American philosopher Charles Sanders Pierce said:

Doubt is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief; while the latter is a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid, or to change to a belief in anything else.

Why Do You Want To Take My Religion Away?

The best defense of religious beliefs and practices is that life is tough and people find religion soothing. I didn’t try to talk my now deceased 86 year-old mother out of her religious beliefs. For one thing it would have been pointless—she believed that her lighting a candle caused me to get my first academic job! Another reason was that it helped her cope—it was her drug of choice. If religion soothes, if it make people’s lives go better or helps them treat others better, fine.

But religious beliefs come at a cost. These includes: inquisitions, religious wars, human sacrifice, collaboration with despotic regimes, persecution of homosexuals, pedophile priests and countless examples of religious cruelty throughout recorded history. As Voltaire said, “Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.” Moreover, religious institutions are often anti-democratic, anti-progressive, misogynistic, medieval and authoritarian. Religion also leads to guilt, shame, and fear.

This doesn’t mean that religion is the worst thing in the world—some good has come from religious beliefs. But evolutionary biology implanted religious tendencies within our brains, and these tendencies need to be abandoned. Human beings need to take control of their destiny. They need to become the protagonists of cosmic evolution. We need to make a better world. No one has more eloquently expressed these hopes than one of our greatest living scientists, E. O. Wilson:

The true Promethean spirit of science means to liberate man by giving him knowledge and some measure of dominion over the physical environment. But at another level, and in a new age, it also constructs the mythology of scientific materialism, guided by the corrective devices of the scientific method, addressed with precise and deliberately affective appeal to the deepest needs of human nature, and kept strong by the blind hopes that the journey on which we are now embarked will be farther and better than the one just completed.[i]

______________________________________________________________________

[i] Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) 209.

Depression: Whose Fault Is It?

I was recently involved in a discussion about someone who had committed suicide. I don’t know the details but evidently the victim was a successful, mid-career man, suffering from depression. A major contributing factor was job stress. Here is how the dialogue went:

A Tough Guy (TG)- The guy was stupid and weak-minded. He needed to master his thoughts. If his job was stressful, he should have gotten another one. If his thoughts were troubling, he should changed them. If you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.

A Compassionate Guy (CG) – Depression can strike anyone, it is a disease. If you experience enough stress you can have a mental breakdown. Just spend a few hours in a war zone or a few years in a stressful job and you can find out for yourself. If possible you should avoid bad situations, but you can’t always do that. Depressed persons need compassion and professional help.

TG – If you really care about someone tell them not to put themselves in situations where they might get hurt.

CG – Sure. But if they’re already suffering from mental illness it’s too late. By that time they are then in a situation which is beyond their control. At that point free will, if it exists, can’t intervene.

A Former Depressed Guy (FS) – When you are suffering from depression you can’t think rationally, just like when you are physically ill you can’t perform certain physical tasks. Friends helped me get help before I had my own breakdown, but many aren’t that lucky.

A Social Scientist (SS) – It’s problematic to insinuate that the fault with depression or suicide lies within the person. One million people decide to take their life every year, that’s 1.5% of all deaths worldwide. The problem is the system. Many want to get out of the kitchen, but they can’t because the kitchen is the whole world. So we should destroy the kitchen, and rebuild it so that it doesn’t burn us any more.

An Economist (E) – It’s clear that the developed world faces issues related to stress—largely driven by capitalistic modes of production which have reduced the value of individual human experience. Here is an article about South Korea that makes the point.

TG – Don’t blame the world; blame yourself. You decided to become stressed. So change yourself.

SS – We need societal structural change which leads to individual change, which in turn leads to societal change. We need a society based on a new social contract that meets people’s biological and psychological needs. A world where people aren’t forced into competitive environments. A cooperative society based more on social capital than economic capital. A society with work that is stable and psychologically fulfilling.

TG – Until then if you can’t stand the heat get out of the kitchen.

CG – That’s what this talented man did. He followed your advice. That’s not an indictment of him, even by your own standards. It’s an indictment of the world.

December 21, 2014

Torture and the Ticking Time Bomb

(This article appeared in the online magazine of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, December 16, 2014.)

Why do people torture others? Why do they march others into gas chambers? Because some are psychopaths or sadists or power hungry. Depravity is in their DNA.

Some are not inherently depraved but believe the situation demands torture. If others are evil and we are good, then we should kill and torture them with impunity. Such ideas result from the demonization of others, from a simplistic worldview in which good battles evil. If others torture, they are war criminals; if we torture are motives are pure. But the world is more nuanced than this. There is good and evil within us all.

The apologists for torture say they are protecting you. They may believe this but that doesn’t make it true. It may be in their interest to wage war, construct secret torture facilities or incarcerate millions in their home country, but it is probably not in yours. You or your children might be doing the fighting or the torturing, and you might suffer the reprisals from the policies of the rich and powerful. Dick Cheney will get another deferment.

Moreover the torture advocates can easily turn you into instruments of their perversion, unlocking the perversion within you, as the Stanford Prison Experiment shows. If the best government jobs program hires mercenaries, then some sign up. But be warned. Those who were caught and photographed at Abu Ghraib were sentenced to prison—scapegoats for those who authorized the policies. Donald Rumsfeld received a book contract.

So do you really feel safer knowing that your corporate-owned government wages continual warfare and tortures around the world? That they incarcerate millions of their own citizens in high-tech dungeons? That thousands languish in solitary confinement for years, some since they were children? That police often kill without repercussions? You may suffer no blowback. Perhaps your nationality, race or socio-economic class will shield you. But the depravity sown may also be reaped. If you are not among the rich and the powerful, the judge will not be lenient. If you are captured in a foreign land, being an American is not a plus.

Now I can construct thought experiments to justify torture or almost anything else. Should I imprison, torture or kill one to save a hundred? A utilitarian calculation says yes, one is less than a hundred. Torture’s defenders invoke such stories. They especially like the ticking time bomb scenario. It goes like this.

There is a ticking time bomb ready to blow up an American city. (If you’ve been to many inner cities in America, you’ll find little left for a bomb to destroy.) The bomb will soon detonate and the man who planted it is in custody. Surely we shouldn’t be squeamish about torturing him to save thousands of lives. Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, a horrific human being, recently defended this argument. Scalia is a Catholic in good standing. So was the Grand Inquisitor.

The ticking time bomb story reminds me of Wittgenstein’s insight that we can be bewitched by a picture, seduced by simplistic examples that misrepresent the world. Think about the problems with this hypothetical story. You may kill this man before getting any relevant information, he may know nothing of the plan, there may be no such plan, or he may lie to stop the torture. In such cases your torturing was for naught, it did nothing but corrupt you. The image cheats because it assumes there is a ticking bomb and you have the man who planted or knows about it. In real life it never works that way.

In real life it works like this. There might be a bomb or an attack planned, and you may or may not have people in custody who knows something relevant. Now how long and how severely should you torture these people? If they don’t talk is that a sign that they don’t know anything or that you should up the torture? If you have twenty prisoners and are sure that one of them knows something important but you don’t know which one, do you torture all twenty? Should you torture suspects’ children to see if that induces them to give you the information you want? (The CIA of the United States threatened detainees in this way.) Remember you don’t know if that will work until you torture their children. How many children do you torture before you stop? In such cases was your torture justified? Was it moral? Or did it engender hatred? Was it counter-productive?

In fact, if you are worried about enemies foreign and domestic, why not torture everyone who is a potential threat—college professors, torture opponents, ACLU members, Buddhist monks, grandmothers and bloggers who don’t like torture. Perhaps the enemies are among us like we thought they were during the McCarthy era. Maybe your colleague in torture is a spy. Should you torture him? Should he torture you?

The picture of the ticking time bomb bewitches because it’s a fabrication. In the real world the choice isn’t one person’s pain versus the suffering of thousands, it is the moral affront of torture and its repercussions versus the possibility of finding something useful. Remember too that the story portrays the decision as a one-time emergency choice, while in the real world decisions are made in the context of procedures and policies. That’s why the following questions need to be asked to. Should we have professional torturers who, like medieval executioners, are schooled in their practices? Maybe a torture major in college? Trade conventions showing the latest high-tech torture devices? These are not idle questions; they need to be addressed if we are to proceed.

So I ask. Do you really want to set a precedent of using barbaric practices that appeal to our worst instincts? Do we want to bring forth from human nature the savagery that which lies just below the surface of civility? Do you really want to create a torture culture and the people who inhabit it? Do you really want torturers walking among us? I think not.