John G. Messerly's Blog, page 126

January 8, 2015

Logical Thinking Decreases Religious Beliefs

A recent study, conducted at the University of British Columbia suggests that analytical thinking can decrease religious belief. Here is the brief summary:

A new study finds that analytic thinking can decrease religious belief, even in devout believers. The study finds that thinking analytically increases disbelief among believers and skeptics alike, shedding important new light on the psychology of religious belief.

If true this is consistent with other findings that among professional philosophers and world-class scientists—those trained in analysis—religious belief is practically non-existent. It is also provides evidence for the main thesis of my recent article “Religion’s Smart-People Problem.”

The study, published in the April 27 issue of Science, found that the negative effect on religious belief caused by thinking analytically applied to both believers and skeptics. This doesn’t surprise me, as the philosophical basis for most religious beliefs is weak at best.

January 7, 2015

David Swenson: “A View of Life”

David Swenson (1876-1940) was a Kierkegaard Scholar who taught at the University of Minnesota in the 1920s and 1930s. In his article, “The Dignity of Human Life,” published in 1949, he argued that humans live not only in the present, but in the past and future. This concern for past and future is distinctively human, and connects them with the eternal.

Here is a beautiful quote from the piece:

Youth is often too sure of its future. The imagination paints the vision of success and fortune in the rosiest tints; the sufferings and disappointments of which one hears are for youth but the exception which proves the rule; the instinctive and blind faith of youth is in the relative happiness of some form of external success. Maturity, on the other hand, has often learned to be content with scraps and fragments, wretched crumbs saved out of the disasters on which its early hopes suffered shipwreck. Youth pursues an ideal that is illusory; age has learned, O wretched wisdom! to do without an ideal altogether. But the ideal is there … and no mirages of happiness or clouds of disappointment, not the stupor of habit or the frivolity of thoughtlessness, can entirely erase the sense of it from the depths of the soul.

Here is a summary of the piece:

To prepare themselves to live in the present, the young need to be trained to contribute to life, to learn the specialized skills that will help them and others. But they need something else—they need “a view of life.” This is not acquired through formal education but is a product of self-knowledge and subjective conviction: “a view of life is the reply a person gives to the question that life asks of him.” Essentially, this view of life is that which will give one’s life meaning, worth, and dignity.

Swenson notes that all persons desire happiness, and those who are unhappy have “failed to realize [their] humanity.” But for thinking beings happiness is not a pleasant momentary enjoyment of the present, but something deeper. Complete happiness requires that life be infused with “a sense of meaning, reason, and worth.” A view of life therefore should answer the following: “What is that happiness which is also a genuine and lasting good?” Aristotle believes that happiness consists in possessing certain really good things that most people desire—creative work, good food, friends, music, aesthetic enjoyment, wealth, freedom, etc.

However Swenson notes a number of problems with this approach. First, this leaves us with so many desires that we are torn by different impulses, and we do not find the peace that comes from devotion to a single end. Second, we are a captive of desires which themselves depend on an external world over which we do not have control. So if we do not fulfill our desires we may fall into despair. Third, most of these things are not intrinsically valuable. Some, like health and beauty are relative; others, like money and power are only good if one knows how to use them.

A final reason to reject the Aristotelian approach is that some people are way ahead in the race for these goods, as they have been bestowed with talents or circumstances that most of us lack. Swenson believes this inequality should be deeply troubling to any sympathetic human being. He argues that he cannot enjoy happiness that others don’t have. That which gives life meaning must be inclusive; it must be something to which all have access. It must be something absolute that underlies life and may be found by all who seek it. “The possibility of making this discovery … is … the fundamental meaning of life, the source of its dignity and worth.” With this discovery comes true happiness.

These considerations lead Swenson to duty which “is the eternal in man.” In ethical considerations we discover the infinite worth of the individual; essentially, we find the eternal in human beings. Nevertheless, humans cannot create their own meaning, since they are derivative of the gods. But they can discover meaning by surrendering to the will of the gods. Swenson knows this message may fall on deaf ears, especially of the young. Youth are idealistic and quixotic; the mature are realistic and sensible. But all must accept that we are equally human; this is the moral realization that lends dignity and meaning to our lives.

_________________________________________________________________________

Swenson, “The Dignity of Human Life,” 23.

January 6, 2015

Antony Flew on Tolstoy and Faith

Antony Garrard Newton Flew (1923 – 2010) was a British philosopher. Belonging to the analytic and evidentialist schools of thought, he was notable for his works on the philosophy of religion and outspoken atheism. Flew taught at the universities of Oxford, Aberdeen, Keele and Reading, and at York University in Toronto. In a 1963 essay titled “Tolstoi and the Meaning of Life,” Flew reconstructs Tolstoy’s argument as follows:

1. if all ends in death then life is meaningless;

2. all ends in death;

3. thus life is meaningless.

4. if life is meaningless then there are no desires that are reasonable to fulfill

5. thus there are no desires that are reasonable to fulfill.

Flew denies that the fact of death necessitates the conclusion that life is meaningless. He also denies that for something to matter it must go on forever. One could argue the opposite, he says, that our mortality gives life its meaning. Flew distinguishes the fact of suffering and death from the evaluative conclusion Tolstoy draws from them—that life is pointless and meaningless. He did not have to draw this conclusion.

Tolstoy also assumed the simple people knew something he did not, since they did not suffer from his condition. But he did not have to draw this conclusion either. The fact that simple people despair less than intellectuals doesn’t mean they possess knowledge of the meaning of life—maybe they just worry about different things than Tolstoy. Moreover, the fact that the peasants were not troubled like Tolstoy says nothing about whether their beliefs were true.

Yet none of this counts against Tolstoy if we don’t interpret him as expounding dogma, but as recommending a way of life. He found a solution to his condition, not in answers to his questions, but in a religious therapy for his symptoms that is itself devoid of cognitive content. Tolstoy found his answer in faith.

January 5, 2015

Leo Tolstoy: Meaning and a Leap of Faith

Leo Tolstoy (1828 –1910) was a Russian writer widely regarded as one of the greatest novelists. His masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina represent some of the best realistic fiction ever penned. He also was known for his literal interpretation of the teachings of Jesus. Tolstoy became a pacifist and Christian anarchist, and his ideas of non-violent resistance influenced Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Near the end of his life, he finally rejected his wealth and privilege and became a wandering ascetic—dying in a train station shortly thereafter.

The following summary is from his short work, “A Confession,” which was written in 1882 and first published in 1884. Tolstoy was one of the first thinkers to pose the problem of life’s meaning in a modern way.

Tolstoy says he wrote to make money, take care of his family, and to distract himself from questions about meaning. But later—when seized with questions about the meaning of life and death—he came to regard his literary work as worthless. Without an answer to questions of meaning, he was incapable of doing anything. Despite fame, fortune, and family, he wanted to kill himself. Being born, he said, was a stupid trick that was played on him. “Sooner or later there would come diseases and death…all my affairs…would sooner or later be forgotten, and I myself would not exist. So why should I worry about all these things?” In short, why should he do anything or care about anything if all is for naught?

The essence of life, Tolstoy thought, was best captured by an Eastern parable of a man hanging onto a branch inside of a well, with a dragon at the bottom, a beast at the top, and the mice eating the branch to which he clings. There is no way out and the pleasures of life—honey on the branch—are ruined by our inevitable death. Everything leads to the truth: “And the truth is death.” This recognition of death and the meaninglessness of life ruin the joy of life.

The sciences provide some knowledge but they do not give comfort. Moreover, the kind of knowledge which would give comfort—knowledge about the meaning of life—does not exist. He was left with the realization that all is incomprehensible. Yet Tolstoy noted that the sense of meaninglessness comes more often to the learned than to the simple people. Thus he began to look to the working class for answers, to individuals who have answered the question of the meaning of life. Tolstoy notes that they did not derive meaning from pleasure, since they had so little of it, and yet they thought suicide to be a great evil.

It seemed then that the meaning of life was not found in any rational, intellectual knowledge but rather “in an irrational knowledge. This irrational knowledge was faith…” Tolstoy says he must choose between reason, from which it follows that there is no meaning, and faith, which entails rejecting reason. What follows is that if reason leads to the conclusion that nothing makes sense, then reason is irrational. And if irrationality leads to meaning, then irrationality is really rational—presuming that one wants meaning rather than truth.

Tolstoy essentially argued that rational, scientific knowledge only gives you the facts. It only relates the finite to the finite, it does not relate a finite life to anything infinite. So that “no matter how irrational and monstrous the answers might be that faith gave, they had this advantage that they introduced into each answer the relation of the finite to the infinite, without which there could be no answer.” Only by accepting irrational things—the central tenets of Christianity—could one find an answer to the meaning of life.

So one must have faith, but what is faith? For Tolstoy “faith was the knowledge of the meaning of human life…Faith is the power of life. If a man lives he believes in something.” And he found this faith, not in the wealthy or the intellectuals, but in the poor and uneducated. The meaning given to the simple life by simple people … that was the meaning Tolstoy accepted. Meaning is found in a simple life and religious faith.

Summary – For Tolstoy questions about the meaning of life are crucial, but our rational science cannot answer these questions. Thus we must adopt a non-rational solution; we must accept the non-rational faith of the simple person. Ironically, this non-rational faith is rational, since it provides a way to live.

While I understand and sympathize with Tolstoy’s sentiments, I can’t accept his solution to the problem of life. I have written extensively on this blog about why I reject the religious solution to the problem of life, writings my readers can easily find. Rather than reiterate what I’ve said many times before I’ll let that great Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis speak for me.

Nietzsche taught me to distrust every optimistic theory. I knew that man’s womanish heart has constant need of consolation, a need to which that super-shrewd sophist the mind is constantly ready to minister. I began to feel that every religion which promises to fulfill human desires is simply a refuge for the timid, and unworthy of a true man. … We ought, therefore, to choose the most hopeless of world views, and if by chance we are deceiving ourselves and hope does exist, so much the better. At all events, in this way man’s soul will not be humiliated, and neither God nor the devil will ever be able to ridicule it by saying that it became intoxicated like a hashish-smoker and fashioned an imaginary paradise out of naiveté and cowardice—in order to cover the abyss. The faith most devoid of hope seemed to me not the truest, perhaps, but surely the most valorous. I considered the metaphysical hope alluring bait which true men do not condescend to nibble. I wanted whatever was most difficult, in other words most worthy of man, of the man who does not whine, entreat, or go about begging.

January 4, 2015

January 3, 2015

The Origin, Evolution, and Fate of the Cosmos

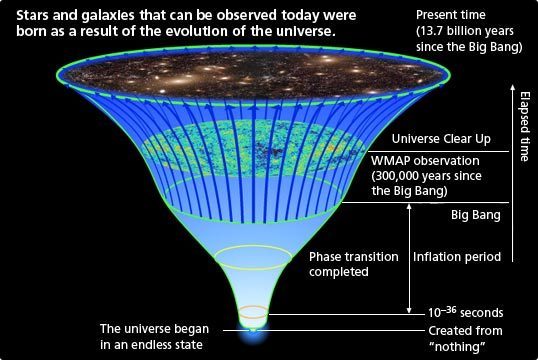

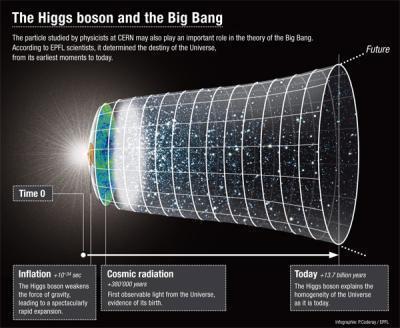

Our universe began about 13.81 billion years ago. (That we know this is a testimony to the power of science. It is truly an astonishing discovery and we are the first living people who have known this.) Cosmology is speculative as to what happened before then but competing ideas include that: 1) the universe emerged from nothingness, space and time were created in the big bang and thus there was no space or time before the big bang; 2) the universe resulted from the movement or collision of membranes (branes), as in string theory; 3) the universe goes through endless self-sustaining cycles where, in some models, the universe expands, contracts, and then bounces back again; and 4) that the universe grew from the death of a previous universe. The last three proposals all argue that the Big Bang was part of a much larger and older universe, or multiverse if you will, and thus not the literal beginning. (For a detailed discussion of these issues see my review of Jim Holt’s Why Does The World Exist?)

Though the details of these and other competing models go beyond the scope of our inquiry, none of them, or any other variants likely to be proposed, have a place in them for supernatural gods. The universe is mysterious, but gods apparently will not play a role in explaining it. Scientific cosmogonies have generally replaced the religious cosmogonies that preceded them among the scientifically literate. The main differences between the two types of cosmogonies are first, that the scientific accounts are supported by good reasons and evidence, and second, there is no obvious place in scientific accounts for meaning. It is not surprising then that many are threatened by a scientific worldview. Even if we are uncertain which if any of the scientific cosmogonies is true, the damage has been done; what we now know of the origin of the universe undermines our previous certainty about gods and the meaning of life.

When we turn to the future of the cosmos the issue is also speculative. The most likely scenarios based on present evidence are that the universe will: 1) reverse its expansion and end in a big crunch; 2) expand indefinitely, exhausting all its heat and energy ending in a big freeze; 3) eventually be torn apart in a big rip; 4) oscillate, contract, and then expand again from another big bang, the big bounce; or 5) never end, since there are an infinite number of universes or multiverses. In none of these scenarios do the gods play a role nor do any of them appear especially conducive to meaning. The important point is that there are now alternative scenarios concerning the fate of the universe that were inconceivable to our ancestors, and these alternatives are not comforting. The mere knowledge of these alternatives undermines our certainty about the meaning of our lives.

However, it should be admitted that science is highly speculative on such matters—these are defeasible scientific claims. Nonetheless, I wouldn’t bet against the ability of science to eventually unravel these great secrets, as the march of scientific knowledge is inexorable, and no positing of a “god of the gaps” is likely to help. Until then the good news is that views such as the multiverse theory at least give us a reason to reject universal death. If universal death was assured, the case against meaning would be overwhelming, but since it is not, meaning may be possible. The bad news is that no scientific theories look obviously conducive to objective meaning. To be fair, we probably don’t know enough about such speculative areas of science to draw strong conclusions about meaning, except to say again that scientific theories about the origin and fate of the cosmos undermine any certainty we might have about such matters.

In between the beginning and end of the cosmos is its evolution. If you think of this inconceivably long period of time it is easy to understand that things must evolve—they change over time. From 13.81 billion years to today there is a long story of cosmic evolution, the outline of which we know in great detail. And human beings, an incredibly late arrival on the cosmic scene, were forged through genetic mutations and environmental selection. This is beyond any reasonable doubt and anyone who tells you differently is either scientifically illiterate or deceiving you. Ernst Mayr, widely considered the twentieth century’s most eminent evolutionary biologist put it this way: “Evolution, as such, is no longer a theory for the modern author. It is as much of a fact as that the earth revolves around the sun.” He added: “Every modern discussion of man’s future, the population explosion, the struggle for existence, the purpose of man and the universe, and man’s place in nature rests on Darwin.”

Therefore there is no way to understand anything about ourselves without understanding evolution—not our bodies, our behaviors, or our beliefs. This is why biology is so crucial to making sense of the human condition; it is the science that makes the study of human nature potentially precise. This does not mean that knowledge of evolution tells us everything about the meaning of life, but that the process of evolution is the indispensable consideration for any serious discussion of the meaning of human life.

In our limited space we cannot discuss all of the implications of evolutionary biology for understanding human life and nature. Suffice it to say that the evolutionary paradigm has been extended by various thinkers since Darwin to apply, not only to our bodies, but to the evolution of our minds and behaviors. When we move the application of the evolutionary paradigm from body to mind we find ourselves dealing with the mind-body problem and evolutionary epistemology; when we move the paradigm from mind to behavior, we are in the realm of the fact-value problem and evolutionary ethics. And I believe that meaning may be something that evolves as the species and ultimately the cosmos evolve.

The importance of evolution for our understanding of meaning extends obviously from biological to cultural evolution. The future that comes about as a result of cultural evolution may itself be the purpose of life; where we are going, more so than were we came from, may provide meaning. Could it be that the process by which we go from the past to the present is itself an unfolding of meaning?

God may be a problem in astrophysics that will stand or fall on the empirical evidence. For more see E.O. Wilson’s “The Biological Basis of Morality” in the Atlantic online April 1998.

The phrase “god of the gaps” refers to the idea that the gods exist in the gaps of current scientific knowledge. The term is generally derogative; i.e., critical of the attempt to use gods to explain phenomena that as yet do not have naturalistic explanations.

This claim is so easy to verify one could construct a separate biography of hundreds of works by experts to justify the claim. You could begin simply by consulting the multiple publications and statements at the website of the National Academy of Sciences. http://www.nationalacademies.org/evolution/Reports.html

For an introduction to this idea see E.O. Wilson’s On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), and Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (New York: Vintage, 1999).

Chapter 2

January 2, 2015

Glarus Switzerland

Direct democracy in Glarus, Switzerland in 2009.

My great-great grandfather, Christopher Messerli, was from Glarus.

This is the little I know of my geneology. I like that the Messerly’s came from Switzerland—a wonderful, peaceful country, famous for their neutrality. They are not war-mongers. I dedicate this post to the memory of my father.)

The city of Glarus, in eastern Switzerland.

PARENTS – John’s Parents:

Benjamin Edward Messerly (Oct 8, 1917 – Jan 3, 1989)

Mary Jane Hurley Messerly (May 1, 1919 – September 18, 2005)

Ben’s siblings: Blanche Helen Messerly Meinert (June 20, 1907 – 1994)

Joseph Fredrick Messerly (Apr 8, 1914 – Oct 8, 1977)

Alice Cecilia Messerly Hardt (March 9, 1921- 2012)

Vernon Forrest Messerly (Feb 21, 1923 – Apr 10, 1974)

Mary Jane’s sibling: Hugh Richard, died at about age 6 before Mary was born.

GRAND PARENTS – Ben’s Parents:

Joseph Louis Messerly (Jan 8, 1888 – Nov 8, 1948)

Alice (christened Else) Stuessie Messerly (Dec 14, 1888 – Jan 26, 1973)

Joseph’s siblings: Louis, Bertha, Otto, John, Mazie

Alice’s siblings: Anna Stuessie Griffin; Ollie Stuessie Killibrew; Emma Stuessie Honnick; Martin Stuessie (Anna’ children: Anna Marie Schuelle, Edgar; Ollie’s: Oris and Lola Wright; Emma was childless; Martin: Estelle, a step-child)

Mary Jane’s Parents:

Joseph Hurley (July 13, 1871 – 1951) Born in Cincinnati Ohio

Stella Roll (Rawl?) Hurley (July 1, 1878 – Dec 18, 1968) Born in Cinncinati Ohio

GREAT-GRANDPARENTS – Joseph Louis Messerly’s parents:

Louis Messerly – Came to St. Louis from England. He was a stove repairman who was originally from Switzerland. He traveled with his brother and did work as they went.

Mary Ellen Sweeney Messerly –Believed born in St. Charles, Mo. Her parents were Catholic and came from Ireland.

Louis’s siblings: He had a brother who lived in London and a sister, Bertha, who married a man named English. Mary’s siblings: Had a twin brother who died.

Alice Stuessie Messerly’s parents:

Christopher Stuessie – (a Protestant. Born in Highland, IL (Oct 1, 1842 – Aug 3, 1904)

Mary Olseuski (Olendowski sp?)– Born in Mariensburg Germany near the Polish border (Jan 13, 1863 – Jun 14, 1911) and came to America when she was 17.

Joseph Hurley’s parents:

Joseph & Mary Hurley – From Ireland.

Stella Hurley Roll’s parents:

Sam & Matilda Jane Roll – believed to be from England. (After Sam died Matilda married William J. Pavey.)

GREAT-GREAT GRANDPARENTS –

Louis Messerly’s parents – from SWITZERLAND (His father was named Christopher Messerli and Christopher’s father was also named Christopher. They were from Glarus Switzerland.) Mary Ellen Sweeney’s parents – from IRELAND; Chris Stuessie’s parents – from GERMANY. Mary Olseuski’s parents – from GERMANY? POLAND?

Joseph Hurley’s parents – from IRELAND? Mary Hurley’s parents – from IRELAND?

Sam Roll parent’s -? Matilda Roll’s parents -?

January 1, 2015

Religion’s Smart-People Problem

(This is the unedited version of my article which appeared in Salon, December 21, 2014.)

Should you believe in a God? Not according to most academic philosophers. A comprehensive survey revealed that only about 14% of English-speaking professional philosophers are theists. As for what little religious belief remains among their colleagues, most professional philosophers regard it as a strange aberration among otherwise intelligent people. Among scientists the situation is much the same. Surveys of the members of the national academy of sciences, comprised of the most prestigious scientists in the world, show that religious belief among them is practically non-existent, about 7%.

Now nothing definitely follows about the truth of a belief from what the majority of philosophers or scientists think. But such facts might cause believers discomfort. There has been a dramatic change in the last few centuries in the proportion of believers among the highly educated in the Western world. In the European Middle Ages belief in a God was ubiquitous, while today it is rare among the intelligentsia. This change occurred primarily because of the rise of modern science and a consensus among philosophers that arguments for the existence of gods, souls, afterlife and the like were unconvincing. Still, despite the view of professional philosophers and world-class scientists, religious beliefs have a universal appeal. What explains this?

Genes and environment explain human beliefs and behaviors—people do things because they are genomes in environments. The near universal appeal of religious belief suggests a biological component to religious beliefs and practices, and science increasingly confirms this view. There is a scientific consensus that our brains have been subject to natural selection. So what survival and reproductive roles might religious beliefs and practices have played in our evolutionary history? What mechanisms caused the mind to evolve toward religious beliefs and practices?

Today there are two basic explanations offered. One says that religion evolved by natural selection—religion is an adaptation that provides an evolutionary advantage. For example religion may have evolved to enhance social cohesion and cooperation—it may have helped groups survive. The other explanation claims that religious beliefs and practices arose as by-products of other adaptive traits. For example, intelligence is an adaptation which aids survival. Yet it also forms casual narratives for natural occurrences and postulates the existence of other minds. Thus the idea of hidden Gods explaining natural events was born.

In addition to the biological basis for religious belief, there are environmental explanations. It is self-evident from the fact that religions are predominant in certain geographical areas but not others, that birthplace strongly influences religious belief. This suggests that people’s religious beliefs are, in large part, accidents of birth. Besides cultural influences there is the family—the best predictor of people’s religious beliefs in individuals is the religiosity of their parents. There are also social factors effecting religious belief. For example, a significant body of scientific evidence suggests that popular religion results from social dysfunction. Religion may be a coping mechanism for the stress caused by the lack of a good social safety net—hence the vast disparity between religious belief in Western Europe and the United States.

There is also a strong correlation between religious belief and various measures of social dysfunction including homicides, the proportion of people incarcerated, infant mortality, sexually transmitted diseases, teenage births, abortions, corruption, income inequality and more. While no causal relationship has been established, a United Nations list of the twenty best countries to live in shows the least religious nations generally at the top. Only in the United States, which was ranked as the 13th best country to live in, is religious belief strong relative to other countries. Moreover virtually all the countries with comparatively little religious belief ranked high on the list of best countries, while the majority of countries with strong religious belief ranked low. While correlation does not equal causation, the evidence should give pause to religion’s defenders. There are good reasons to doubt that religious belief makes people’s lives go better, and good reasons to believe that they make their lives go worse.

Despite all this most people still accept some religious claims. But this fact doesn’t give us much reason to accept religious claims. People believe many weird things which are completely irrational—astrology, fortune-telling, alien abductions, telekinesis, and mind reading—and reject claims supported by an overwhelming body of evidence—biological evolution for example. More than three times as many Americans believe in the virgin birth of Jesus than in biological evolution, although few theologians take the former seriously, while no serious biologists rejects the latter!

Consider too that scientists don’t take surveys of the public to determine whether relativity or evolutionary theory are true, their truth is assured by the evidence as well as by resulting technologies—global positioning and flu vaccines work. With the wonders of science everyday attesting to its truth, why do many prefer superstition and pseudo science? The simplest answer is that people believe what they want to, what they find comforting, not what the evidence supports: In general people don’t want to know; they want to believe. This best summarizes why people tend to believe.

Why then do some highly educated people believe religious claims? First, smart persons are good at defending ideas that they originally believed for non-smart reasons. They want to believe something, say for emotional reasons, and they then become adept at defending those beliefs. No rational person would say there is more evidence for creation science than biological evolution, but the former satisfies some psychological need for many that the latter does not. How else to explain the hubris of the philosopher or theologian who knows little of biology or physics yet denies the findings of those sciences? It is arrogant of those with no scientific credentials and no experience in the field or laboratory, to reject the hard earned knowledge of the science. Still they do it. (I knew a professional philosopher who doubted both evolution and climate science but believed he could prove that the Christian God must take a Trinitarian form! Surely something emotional had short-circuited his rational faculties.)

Second, the proclamations of educated believers are not always to be taken at face value. Many don’t believe religious claims but think them useful. They fear that in their absence others will lose a basis for hope, morality, or meaning. These educated believers may believe that ordinary folks can’t handle the truth. They may feel it heartless to tell parents of a dying child that their little one doesn’t go to a better place. They may want to give bread to the masses, like Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor.

Our sophisticated believers may be manipulating, using religion as a mechanism of social control as Gibbon noted long ago: “The various modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosophers as equally false; and by the magistrate as equally useful.” Consider the so-called religiosity of many contemporary politicians, whose actions belie the claim that they really believe the precepts of the religions to which they supposedly subcribe. Individuals may also profess belief because it is socially unacceptable not to—they don’t want to be out of the mainstream or fear they will not be re-elected or loved if they profess otherwise. So-called believers may not believe the truth of their claims; instead they may think that others are better off or more easily controlled if those others believe. Or perhaps they may just want to be socially accepted.

Third, when sophisticated thinkers claim to be religious, they often have something in mind unlike what the general populace believes. They may be process theologians who argue that god is not omnipotent, contains the world, and changes. They may identify god as an anti-entropic force pervading the universe leading it to higher levels of organization. They may be pantheists, panentheists, or death of god theologians. Yet these sophisticated varieties of religious belief bears little resemblance to popular religion. The masses would be astonished to discover how far such beliefs deviate from their theism.

But we shouldn’t be deceived. Although there are many educated religious believers, including some philosophers and scientists, religious belief declines with educational attainment, particularly with scientific education. Studies also show that religious belief declines among those with higher IQs. Hawking, Dennett and Dawkins are not outliers, and neither are Bill Gates or Warren Buffett.

Or consider this anecdotal evidence. Among the intelligentsia it is common and widespread to find individuals who lost childhood religious beliefs as their education in philosophy and the sciences advanced. By contrast, it is almost unheard of to find disbelievers in youth who came to belief as their education progressed. This asymmetry is significant; advancing education is detrimental to religious belief. This suggest another part of the explanation for religious belief—scientific illiteracy.

If we combine reasonable explanations of the origin of religious beliefs and the small amount of belief among the intelligentsia with the problematic nature of beliefs in gods, souls, afterlives, or supernatural phenomena generally, we can conclude that (supernatural) religious beliefs are probably false. And we should remember that the burden of proof is not on the disbeliever to demonstrate there are no gods, but on believers to demonstrate that there are. A believer is not justified in affirming their belief on the basis of another’s inability to show conclusively refute them, anymore than a believer in invisible elephants can command my assent on the basis of my not being able to “disprove” the existence of the aforementioned elephants. If the believer can’t provide evidence for a god’s existence, then I have no reason to believe in gods.

In response to the difficulties with providing reasons to believe in things unseen, combined with the various explanations of belief, you might turn to faith. It is easy to believe something without good reasons if you are determined to do so—like the queen in Alice and Wonderland who “sometimes … believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” But there are problems with this approach. First, if you defend such beliefs by claiming that you have a right to your opinion, however unsupported by evidence it might be, you are referring to a political or legal right, not an epistemic one. You may have a legal right to say whatever you want, but you have epistemic justification only if there are good reasons and evidence to support your claim. If someone makes a claim without concern for reasons and evidence, we should conclude that they simply don’t care about what’s true. We shouldn’t conclude that their beliefs are true because they are fervency held.

Another problem is that fideism—basing one’s beliefs exclusively on faith—makes belief arbitrary, leaving no way to distinguish one religious belief from another. Fideism allows no reason to favor your preferred beliefs or superstitions over others. If I must accept your beliefs without evidence, then you must accept mine, no matter what absurdity I believe in. But is belief without reason and evidence worthy of rational beings? Doesn’t it perpetuate the cycle of superstition and ignorance that has historically enslaved us? I agree with W.K. Clifford. “It is wrong always, everywhere and for everyone to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.” Why? Because your beliefs affect other people, and your false beliefs may harm them.

The counter to Clifford’s evidentialism has been captured by thinkers like Blaise Pascal, William James, and Miguel de Unamuno. Pascal’s famous dictum expresses: “The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of.” William James claimed that reason can’t resolve all issues and so we are sometimes justified believing ideas which work for us. Unamuno searched for answers to existential questions, counseling us to abandon rationalism and embrace faith. Such proposals are probably the best the religious can muster, but if reason can’t resolve our questions then agnosticism, not faith, is required.

Besides, faith without reason doesn’t satisfy most of us, hence our willingness to seek reasons to believe. If those reasons are not convincing, if you conclude that religious beliefs are untrue, then religious answers to life’s questions are worthless. You might comfort yourself by believing that little green dogs in the sky care for you but this is just nonsense, as are any answers attached to such nonsense. Religion may help us in the way that whisky helps a drunk, but we don’t want to go through life drunk. If religious beliefs are just vulgar superstitions, then we are basing our lives on delusions. And who would want to do that?

Why is all this important? Because human beings need their childhood to end; they need to face life with all its bleakness and beauty, its lust and its love, its war and its peace. They need to make to make the world better. No one else will.

December 31, 2014

Scientific Facts and Meaning

Our last post argued that facts are relevant to the meaning of our lives. Scientific facts are especially germane, since you can’t have a coherent picture of the world without some understanding of modern science. Why? Because science is the only cognitive authority in the world today. Yes, there are things that science has not or cannot discover and scientific theories are always provisional. Still the well established truths of science should be the starting point for serious inquiry into the human condition—theoretical musings are no substitute for empirical evidence. To understand the world and our place within it, we must begin with the knowledge of modern science.

But which parts of science are most relevant to the meaning of life? The problem is that the scientific areas most relevant to our inquiry—anthropology, psychology, sociology, and history—are imprecise sciences; and those least relevant to our concerns—mathematics, physics, and chemistry—are the most precise. If a science is to help our search for meaning, it must be both precise and relevant to our concerns. Are there such areas of science?

Cosmology and biology would be those sciences. Both are precise and both have important things to say about the meaning of life. Cosmology, broadly conceived as referring to the current state of the universe as well as to it origin and fate, is obviously applicable. Biology is also important; it tells us what human nature is. To understand the question of the meaning of life we need to understand the origin and fate of both the universe and ourselves. must have a basic understanding of these sciences.

_________________________________________________________________________

I would argue that science, not philosophy discovers truth. Philosophy should concern itself with values and meaning. For more see Jean Piaget’s The Insights and Illusions of Philosophy (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977).

December 30, 2014

Facts and Meaning

Facts and meaning are related. We infer the meaning of our lives from facts about ourselves and the world, mindful that the conclusions we draw from facts are provisional. Yet modern philosophers hesitate to draw philosophical conclusions—especially about values—from facts. In the early twentieth-century many philosophers charged those who drew such conclusions with committing the naturalistic fallacy—inferring what ought to be the case from what is the case. For example, it may be a fact that humans are innately aggressive, but nothing follows from that about whether they should be. We cannot derive values from facts or get ought from is if the naturalistic fallacy is valid.

While it is generally agreed that we cannot deduce facts from values, facts are still relevant to values. From that fact of our humanity we infer that some things are good for us—like food, health, knowledge, and friendship. We also assume that some things are bad for us— like pain, starvation, ignorance, and loneliness. If our nature were different, our values would be too. If we were angels, we would not need food; if we were rocks, we would not need friends. The fact that projectiles can pierce our brains doesn’t by itself imply that shooting someone is immoral, but if projectiles hitting our brains made us feel good rather than harming us, then the moral prohibition against shooting projectiles at human brains would disappear. Facts tell us tell us something values.

Facts are also relevant to meaning. When modern science uncovered new facts—that the earth was not at the center of the solar system or natural selection rather than the gods made us—our confidence in meaning was shaken. New facts challenge our conception of meaning. Whether I am an angel, a modified monkey, or live in a computer simulation matters, whether I die or am immortal, are all facts that matter in evaluating the meaning of life. There can be no understanding of the meaning of life unless we consider known truths about ourselves and the universe. In our next post we will discuss why the truths revealed by modern science are especially relevant in our search for the meaning of life.

Share

Share