John G. Messerly's Blog, page 102

November 24, 2015

Westphal & Cherry: “Is Life Absurd?”

Jonathan Westphal is currently a visiting professor of philosophy at Hampshire College. He received his B.A. from Harvard College, M.A. from the University of Sussex, and PhD from the University of London. Christopher Cherry is Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Kent in Canterbury England. Their 1990 article, “Is Life Absurd?” offers a critique of Nagel’s claim that life is absurd.

The authors claim first that Nagel offers no reason why we should take the external perspective from which the value of every human concern is cast into doubt. More importantly, some values are immune to Nagel’s critique. Westphal and Cherry give the example of someone absorbed in music. Such an individual cannot entertain the idea that music is worthless, and their attention to music destroys the external point of view. If you are moved by Bach, you cannot at the same time claim the music is pointless. In fact, the only way to truly describe this musical experience is by its subjective emotional value. If we find Bach’s Brandenburg concertos soothing, this internal evaluation cannot be captured or negated by the external perspective.

However, this analysis does not apply only to music. If we consider lives lived with humanity and integrity, what is there about the external perspective that damages them or renders them meaningless? After all, many lives are lived without pretense and without any claim that music, art, or literature is objectively valuable. Thus the external perspective has nothing ostentatious or pretentious to negate. Think of the passionate butterfly collector collecting butterflies, or the patient astronomer chronically stars. In these cases is there no hint of pretension or of the eternal perspective. Such persons are just emotionally engaged.

Nagel’s solution to all this is irony, which the authors suggest may appeal to a New York intellectual but not too many others. Why not rather simply ignore the eternal perspective, or dine, have fun, and play backgammon, as Hume’s suggested? Or why not just engage in interesting play or work? Life does not call for a grand response such as defiance or scorn or irony. Instead why not just be absorbed subjectively in music or tennis? Such absorption is far away from the eternal perspective.

Summary – There is no incongruity between our aspirations and pretensions, and reality from the eternal perspective. If we engage ourselves in things in front of us we can ignore the eternal perspective.

November 23, 2015

Summary of Thomas Nagel’s, “The Absurd”

Thomas Nagel (1937- ) is a prominent American philosopher, author of numerous articles and books, and currently University Professor of Philosophy and Law at New York University where he has taught since 1980.

In “The Absurd,” (1971) Nagel asks why people sometimes feel that life is absurd. For example, people sometimes say that life is absurd because nothing we do now will matter in the distant future. But Nagel points out that the corollary of this is that nothing in the distant future matters now: “In particular, it does not matter now that in a million years nothing we do now will matter.” Furthermore, even if what we do now does matter in a distant future, how does that prevent our present actions from being absurd? In other words, if our present actions are absurd then their mattering in the distant future can hardly give them meaning. For the mattering in the distant future to be important things must matter now. And if I claim definitely that what I do now will not matter in a million years then either: a) I claim to know something about the future that I don’t know; or b) have simply assumed what I’m trying to prove—that what I do will not matter in the future. Thus the real question is whether things matter now—since no appeals to the distant future seem to help us answer that question.

Consider next the argument that our lives are absurd because we live in a tiny speck of a vast cosmos or in a small sliver of time. Nagel argues that neither of these concerns makes life absurd. This is evident because even if we were immortal or large enough to fill the universe, this would not change the fact that our lives could be absurd. Another argument appeals to death, to the fact that everything ends, and reasons to the conclusion that there is no final purpose for our actions. Nagel replies that many of the things we do in life find their justification in the present moment—when I am hungry I eat! Moreover, if the chain of justification must always lead to another justification, we would be caught in an infinite regress. In short, since justification must end somewhere if it is to be justification at all, it might as well end in life. Nagel concludes that the arguments just outlined fail but adds: “Yet I believe they attempt to express something that is difficult to state but fundamentally correct.”

For Nagel the discrepancy between the importance we place on our lives from a subjective point of view and how gratuitous they appear objectively is the essence of the absurdity of our lives. “… the collision between the seriousness with which we take our lives and the perpetual possibility of regarding everything about which we are serious as arbitrary, or open to doubt.” And, short of escaping life altogether, there is no way to reconcile the absurdity resulting from our pretensions and the nature of reality. This analysis rests on two points: 1) the extent to which we must take our lives seriously; and 2) the extent to which, from a certain point of view, our lives appear insignificant. The first point rests on the evidence of the planning, calculation, and concerns with which we invest in our lives.

Think of how an ordinary individual sweats over his appearance, his health, his sex life, his emotional honesty, his social utility, his self-knowledge, the quality of his ties with family, colleagues, and friends, how well he does his job, whether he understands the world and what is going on in it. Leading a human life is full-time occupation to which everyone devotes decades of intense concern.

The second point rests on the reflections we all have about whether life is worth it. Usually after a period of reflection, we just stop thinking about it and proceed with our lives.

To avoid this absurdity we try to supply meaning to our lives through our role “in something larger than ourselves… in service to society, the state, the revolution, the progress of history, the advance of science, or religion and the glory of God.” But this larger thing must itself be significant if our lives are to have meaning by participating in it; in other words, we can ask the same question about meaning of this larger purpose as we can of our lives—what do they mean? So when does this quest for justification end? According to Nagel it ends when we want it to. We can end the search in the experiences of our lives or in being part of a divine plan. But wherever we end the search, we end it arbitrarily. Once we have begun to wonder what the point of it all is; we can always ask of any proposed answer—and what is the point of that? “Once the fundamental doubt has begun, it cannot be laid to rest.” In fact there is no imaginable world that could settle our doubts about its meaning.

Nagel further argues that reflection about our lives does not reveal that they are insignificant compared to what is really important, but that our lives are only significant by reference to themselves. So when we step back and reflect on our lives, we contrast the pretensions we have about the meaning of them with the larger perspective in which no standards of meaning can be discovered.

Nagel contrasts his position on the absurd with epistemological skepticism. Skepticism transcends the limitations of thoughts by recognizing the limitations of thought. But after we have stepped back from our beliefs and their supposed justifications we do not then contrast the way reality appears with an alternative reality. Skepticism implies that we do not know what reality is. Similarly when we step back from life we do not find what is really significant. We just continue to live taking life for granted in the same way we take appearances for granted. But something has changed. Although in the one case we continue to believe the external world exists and in the other case we continue to pursue our lives with seriousness, we are now filled with irony and resignation. “Unable to abandon the natural responses on which they depend, we take them back, like a spouse who has run off with someone else and then decided to return; but we regard them differently…” Still, we continue to put effort into our lives no matter what reason has to say about the irony of our seriousness.

Our ability to step back from our lives and view them from a cosmic perspective makes them seem all the more absurd. So what then are our options? 1) We could refuse to take this transcendental step back but that would be to acknowledge that there was such a perspective, the vision of which would always be with us. So we cannot do this consciously. 2) We could abandon the subjective viewpoint (our earthly lives) and identify with the objective viewpoint entirely, but this requires taking oneself so seriously as an individual that we may undermine the attempt to avoid the subjective. 3) We could also respond to our animalistic natures only and achieve a life that would not be meaningful, but at least less absurd than the lives of those who were conscious of the transcendental stance. But surely this approach would have psychological costs. “And that is the main condition of absurdity—the dragooning of an unconvinced transcendent consciousness into the service of an imminent, limited enterprise like a human life.”

But we need not feel that the absurdity of our lives presents us with a problem to be solved, or that we ought to respond with Camus’ defiance. Instead Nagel regards our recognition of absurdity as “a manifestation of our most advanced and interesting characteristics.” It is possible only because thought transcends itself. And by recognizing our true situation we no longer have reason to resent or escape our fate. He thus counsels that we regard our lives as ironic. It is simply ironic that we take our lives so seriously when nothing is serious at all; this is the incongruity between what we expect and reality. Still, in the end, it does not matter that nothing matters from the objective view, so we should simply chuckle at the absurdity of our lives.

Summary – Life has no objective meaning and there is no reason to think we can give it any meaning at all. Still, we continue to live and should respond, not with defiance or despair, but with an ironic smile. Life is not as important and meaningful as we may have once suspected, but this is not a cause for sadness.

______________________________________________________________________

Nagel, “The Absurd,” 152.

November 22, 2015

Summary of Albert Camus’ “The Myth of Sisyphus”

Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) was a French author, philosopher, and journalist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. His most famous works were the novels La Peste (The Plague) and L’Étranger (The Stranger) and the philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus. He died in a car accident in France.

In “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1955) Camus claims that the only important philosophical question is suicide—should we continue to live or not? The rest is secondary, says Camus, because no one dies for scientific or philosophical arguments, usually abandoning them when their life is at risk. Yet people do take their own lives because they judge them meaningless or sacrifice them for meaningful causes. This suggests that questions of meaning supersede all other scientific or philosophical questions. As Camus puts it: “I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.”

What interests Camus is what leads to suicide. He argues that “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined … the worm is in man’s heart.” When we start to think we open up the possibility that all we valued previously, including our belief in life’s goodness, may be subverted. This rejection of life emanates from deep within, and this is where its source must be sought. For Camus killing yourself is admitting that all of the habits and effort needed for living are not worth the trouble. As long as we accept reasons for life’s meaning we continue, but as soon as we reject these reasons we become alienated—we become strangers from the world. This feeling of separation from the world Camus terms absurdity, a sensation that may lead to suicide. Still most of us go on because we are attached to the world; we continue to live out of habit.

But is suicide a solution to the absurdity of life? For those who believe in life’s absurdity it is a reasonable response—one’s conduct should follow from one’s beliefs. Of course conduct does not always follow from belief. Individuals argue for suicide but continue to live; others profess that there is a meaning to life and choose suicide. Yet most persons are attached to this world by instinct, by a will to live that precedes philosophical reflection. Thus they evade questions of suicide and meaning by combining instinct with the hope that something gives life meaning. Yet the repetitiveness of life brings absurdity back to consciousness. In Camus’ words: “Rising, streetcar, four hours in the office or factory, meal, four hours of work, meal, sleep, and Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday…” Living brings the question of suicide back, forcing a person to confront and answer this essential question.

Yet of death we know nothing. “This heart within me I can feel, and I judge that it exists. This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction.” Furthermore I cannot know myself intimately anymore than I can know death. “This very heart which is mine will forever remain indefinable to me. Between the certainty I have of my existence and the content I try to give to that assurance, the gap will never be filled. Forever I shall be a stranger to myself …” We know that we feel, but our knowledge of ourselves ends there.

What makes life absurd is our inability to know ourselves and the world’s meaning even though we desire such knowledge. “…what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart.”The world could have meaning: “But I know that I do not know that meaning and that it is impossible for me just now to know it.” This tension between our desire to know meaning and the impossibility of knowing it is a most important truth. We are tempted to leap into faith, but the honest know that they do not understand; they must learn “to live without appeal…” In this sense we are free—living without higher purposes, living without appeal. Aware of our condition we exercise our freedom and revolt against the absurd—this is the best we can do.

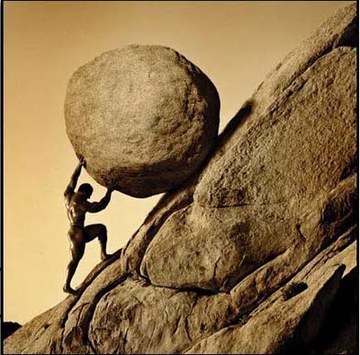

Nowhere is the essence of the human condition made clearer than in the Myth of Sisyphus. Condemned by the gods to roll a rock to the top of a mountain, whereupon its own weight makes it fall back down again, Sisyphus was condemned to this perpetually futile labor. His crimes seem slight, yet his preference for the natural world instead of the underworld incurred the wrath of the gods: “His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing.” He was condemned to everlasting torment and the accompanying despair of knowing that his labor was futile.

Yet Camus sees something else in Sisyphus at that moment when he goes back down the mountain. Consciousness of his fate is the tragedy; yet consciousness also allows Sisyphus to scorn the gods which provides a small measure of satisfaction. Tragedy and happiness go together; this is the state of the world that we must accept. Fate decries that there is no purpose for our lives, but one can respond bravely to their situation: “This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Reflections – Camus argues that life is meaningless and absurd yet we can revolt against the absurdity and find some small modicum of happiness. Essentially Camus asks if there is a third alternative between acceptance of life’s absurdity or its denial by embracing dubious metaphysical propositions. Can we live without the hope that life is meaningful but without the despair that leads to suicide? If the contrast is posed this starkly it seems an alternative appears—we can proceed defiantly forward. We can live without faith, without hope, and without appeal.

I believe we are called upon to live without appeal, all appeals are intellectually dishonest. But perhaps there are alternatives between accepting absurdity and hopeful metaphysics besides Camus’ defiance. Perhaps we can embrace realities current absurdity, reject speculative metaphysics, and ground the meaning of our lives in the small part we can play in transforming the world into a more meaningful reality. We reject absurdity, religion, and anger. Instead we work to transform reality.

_______________________________________________________________________

Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” 81.

November 21, 2015

But man, proud man, Drest in a little brief authority …

Watching and listening to so many politicians, clergy, evangelists, television blowhards, and ordinary citizens in my country today reminds me of one of my favorite passages in all of world literature. It is from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, and it occurs when the character Isabella begs for the life of her brother, Claudio, who has been condemned to death for impregnating his fiancée before they were married.

But man, proud man,

Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d;

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven,

As make the angels weep.

When I hear those vying for the most important political position in the country court the support of those who advocate death for people with certain sexual orientations, and want to kill thousands of innocent civilians—to say nothing of denying homes for refugees, mass incarceration, solitary confinement, denial of health-care and more—it reminds me that puritanical legal codes, barbaric punishments, and general ape-brain ignorance are still with us. It reminds me of how those who know so little—of biology, psychology, history, culture, political philosophy and more—propound on those topics nevertheless.

The ignorant are so self-assured. They know nothing of the the people they despise, of the countries they bomb, and of the people they punish, but they don’t doubt their own infallibility. They know nothing of economics or climatology, of science or technology, of culture or history, but they correct the experts. And why not? They don’t believe in experts anyway.

They are angry apes—as Shakespeare said centuries before Darwin confirmed the fact. They have no knowledge; they have no self-knowledge. We are not angels; we are modified monkeys, all of us. Of course there are no angels, but if there were they would surely weep at the spectacle. Given a little fame, a little fortune, a little authority, and the apes become so self-assured.

November 20, 2015

Commentary on Schopenhauer’s “On the Vanity of Existence”

(I discussed Schopenhauer previously, here and here.)

In focusing upon the movement of time Schopenhauer has zeroed in on a fundamental fact of life which may render it meaningless—the sense in which we can never be in the present and savor it, as life is always slipping through our grasp. I don’t think he is correct when he says that the past is no longer real—the present is partly the result of what happened in the past; the past is partly instantiated in the present. But he is correct that the present is ephemeral, disappears quickly, and much of it seems to vanish into nothingness. Enjoying the present is difficult for these very reasons. Life does hurry us along, and we are incapable of stopping its relentless march. Life is fleeting.

Schopenhauer is also correct that we do strive for successes to avoid boredom, but I think this says more about us than it does about life—life may not be boring, we may be! Those with rich and passionate inner lives find many things interesting. The fact that our striving can be so compelling to us suggests that life does not have to be boring; we may choose to make our lives interesting.

But Schopenhauer has a response to all this. All our striving is in vain because of death; the goal of our being is non-being. He may be mistaken that death implies that our lives have no value, but certainly they have less value because of death. If you honestly consider the trajectory of our lives from birth to infirmity and death—there is a vanity to life. In the end Schopenhauer’s analysis is fundamentally right: suffering, the transience of the present, the awareness of death, and fact of death, all detract from the possibility of a meaningful life. His case against meaningfulness is strong indeed. But that doesn’t mean its the end of the story.

November 19, 2015

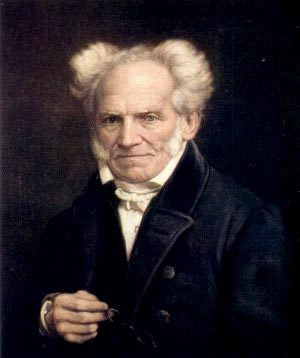

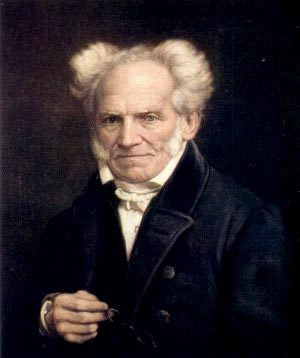

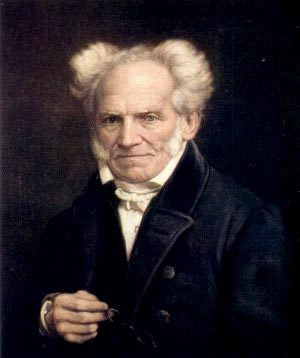

Summary of Arthur Schopenhauer’s, “On the Vanity of Existence””

In “On the Vanity of Existence,” Schopenhauer argues that life’s futility:

is revealed in the whole form existence assumes: in the infiniteness of time and space contrasted with the finiteness of the individual in both; in the fleeting present as the sole form in which actuality exists; in the contingency and relativity of all things; in continual becoming without being; in continual desire without satisfaction; in the continual frustration of striving of which life consists. Time and that perishability of all things existing in time that time itself brings about is simply the form under which the will to live, which as thing in itself is imperishable, reveals to itself the vanity of its striving. Time is that by virtue of which everything becomes nothingness in our hands and loses all real value.

The past is no longer real and thus “it exists as little as does that which has never been.” The present compares to the past as something does to nothing. We came from nothing after eons of time and will shortly return to nothing. Each moment of life is transitory and fleeting and quickly becomes the past—in other words, vanish into nothingness. The hourglass of our lives is slowly emptying. In response one might simply try to enjoy the present, but since the present so quickly becomes the past it “cannot be worth any serious effort.”

Existence rests in the fleeting present; it is thus always in motion, resembling “a man running down a mountain who would fall over if he tried to stop and can stay on his feet only by running on… Thus existence is typified by unrest.” Such a life is one of striving continually for what can seldom be attained or what, when attained, quickly disappoints. We live life hurrying toward the future but also regretting what is past—while the present we regard as merely the way to the future. When looking back on our lives we find that they were not really enjoyed, but instead experienced as merely the way to the future. Our lives were all those present moments that seemed so impossible to enjoy.

What is life then? It is a task where we strive to sustain our lives and avoid boredom says Schopenhauer. Such a life is a mistake:

Man is a compound of needs which are hard to satisfy; that their satisfaction achieves nothing but a painless condition in which he is only given over to boredom; and that boredom is a direct proof that existence is in itself valueless, for boredom is nothing other than the sensation of the emptiness of existence. For if life, in the desire for which our essence and existence consists, possessed in itself a positive value and real content, then there would be no such thing as boredom: mere existence would fulfill and satisfy us. As things are, we take no pleasure in existence except when we are striving after something—in which case distance and difficulties make our goal look as if it would satisfy us (an illusion which fades when we reach it)—or when engaged in purely intellectual activity, in which case we are really stepping out of life so as to regard it from outside, like spectators at a play. Even sensual pleasure itself consists in a continual striving and ceases as soon as its goal is reached. Whenever we are not involved in one or other of these things but directed back to existence itself we are overtaken by its worthlessness and vanity and this is the sensation called boredom.

That our will to live will eventually be extinguished is “nature’s unambiguous declaration that all the striving of this will is essentially vain. If it were something possessing value in itself, something which ought unconditionally to exist, it would not have non-being as its goal.” We begin our lives in the bodily desires of other persons and end as corpses.

And the road from the one to the other too goes, in regard to our well-being and enjoyment of life, steadily downhill: happily dreaming childhood, exultant youth, toil-filled years of manhood, infirm and often wretched old age, the torment of the last illness and finally the throes of death—does it not look as if existence were an error the consequences of which gradually grow more and more manifest?

Summary – The finitude of existence, the ephemeral nature of the present, the contingency of life, the non-existence of the past, the constancy of need, the experience of boredom, and, most importantly the inevitability of death, all lead to the conclusion that life is pointless.

_______________________________________________________________________

Schopenhauer, “On the Vanity of Existence,” 70.

November 18, 2015

Commentary on Schopenhauer’s “On the Sufferings of the World”

I think Schopenhauer’s philosophical insights are generally underrated by philosophers, which is in large part due to their supposed pessimism. (I discussed Schopenhauer in yesterday’s post.) They should be considered as a clarion call to look at life more realistically and improve it. Seen thus, his philosophy is not so pessimistic after all.

Schopenhauer is correct that suffering is real; philosophers who think it merely a privation of good are deceiving themselves. If we bring pain or evil to an end we experience happiness—surely this suggests that suffering is real. There is also something intuitive about the idea that the pleasure we look forward to often disappoints, whereas pain is often unendurable. How often have you looked forward to something whose reality disappointed? In Schopenhauer’s graphic image the pleasure of eating does not compare with the horror of being eaten. However, this comparison is unfair, since we eat many times and can only be eaten once—naturally eating a single time cannot compare in pleasure to the terror of being eaten. A better comparison would be a lifetime of eating versus one moment of being eaten. We can certainly imagine that one would opt for multiple culinary pleasures in exchange for being quickly eaten at some later time

Schopenhauer’s idea that we are like lambs waiting to be slaughtered is an even more powerful image. We are sympathetic to the lambs, cows, and pigs as they await their fates, but ours is not much different. We typically wait longer for our death, and the field in which we are fenced may be larger and more interesting, but our end will be similar, even worse if we linger and suffer at the end of life. Just like the animals awaiting slaughter we too cannot escape. Surely there is some sense in which our impending death steals from the joy of life. We are all terminal, all in differing stages of the disease of aging which afflicts us. And this it seems is what holds together his many images and ideas. We cannot stop time; we worry; we slowly realize many of our dreams will never be realized; and we recognize that each day we will grow older and more feeble, leading to an inevitable outcome. It may have been better if we had never existed at all.

It is this consciousness of suffering and death which makes human life worse than animal life, according to Schopenhauer. Yet this argument is not quite convincing, inasmuch as that same consciousness provides benefits for us as opposed to non-human animals. So Schopenhauer’s argument is not completely convincing. Still, although he has not established that the life of the brute is better than that of the human, he has shown something quite powerful—it is not obvious that human animal life is better than non-human animal life. This is no small achievement and ought to be taken seriously. If this argument is correct then humans should change their own nature from an animal one if possible—by using their emerging technologies.

Schopenhauer is also correct that non-human animal suffering is hard to reconcile with Christian theism, as generations of Christian apologists have discovered. Moreover, his Stoic response to the evils of the world is commendable, as is his call for tolerance for the foibles of our fellow travelers. In the end Schopenhauer is correct in his essential message: the sufferings of the world count strongly against its meaningfulness, even if not definitively so.

November 17, 2015

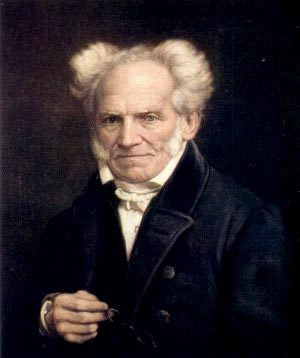

Summary of Arthur Schopenhauer’s, “On the Sufferings of the World”

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) was a German philosopher known for his atheism and pessimism—in fact he is the most prominent pessimist in the entire western philosophical tradition. Schopenhauer’s most influential work, The World as Will and Representation, examines the role of humanity’s most basic motivation, which Schopenhauer called will. His analysis led him to the conclusion that emotional, physical, and sexual desires cause suffering and can never be fulfilled; consequently he favored a lifestyle of negating desires, similar to the teachings of Buddhism and Vedanta. Schopenhauer influenced many thinkers including Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Einstein, and Freud.

In “On the Sufferings of the World” (1851), Schopenhauer boldly claims: “Unless suffering is the direct and immediate object of life, our existence must entirely fail of its aim.” In other words suffering and misfortune are the general rule in life, not the exception. Contradicting what many philosophers had stated previously, Schopenhauer argued that evil is a real thing, with goodness being the lack of evil. We can see this by considering that happiness or satisfaction always imply some state of pain or unhappiness being brought to an end; and by the fact that pleasure is not generally as pleasant as we expect, while pain much worse than imagined. To those who claim that pleasure outweighs pain or that the two balance out, he asks us “to compare the respective feelings of two animals, one of which is engaged in eating the other.” And he quickly follows with another powerful image: “We are like lambs in the field, disporting themselves under the eye of the butcher, who choose out first one and then another for his prey. So it is that in our good days we are all unconscious of the evil Fate may have in store for us—sickness, poverty, mutilation, loss of sight or reason.”

Schopenhauer continues by offering multiple ideas and images meant to bring the reality of human suffering to the fore: a) that time marches on and we cannot stop it—it stops only when we are bored; b) that we spend most of life working, worrying, suffering, and yet even if all our wishes were fulfilled, we would then either be bored or desire suicide; c) in youth we have high hopes but that is because we do not consider what is really in store for us—life, aging, and death. Of our old age Schopenhauer says: “It is bad today, and it will be worse tomorrow; and so on till the worst of all.” d) it would be much better if the earth were lifeless like the moon; life interrupts the “blessed calm” of non-existence; f) if two persons who were friends in youth met in old age, they would feel disappointed in life merely by the sight of each other; they will remember when life promised so much, in youth, and yet delivered so little; g) “If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone, would the human race continue to exist?” Schopenhauer argues that we should not impose the burden of existence on children. He describes his pessimism thus:

I shall be told … that my philosophy is comfortless—because I speak the truth; and people preferred to be assured that everything the Lord has made is good. Go to the priests, then, and leave the philosophers in peace … do not ask us to accommodate our doctrines to the lessons you have been taught. That is what those rascals of sham philosophers will do for you. Ask them for any doctrine you please, and you will get it.

Schopenhauer also argues that non-human animals are happier than human beings, since happiness is basically freedom from pain. The essence of this argument is that the bottom line for both human and non-human animals is pleasure and pain which has as it basis the desire for food, shelter, sex, and the like. Humans are more sensitive to both pleasure and pain, but have much greater passion and emotion regarding their desires. This passion results from human beings ability to reflect upon the past and future, leaving them susceptible to both ecstasy and despair. Humans try to increase their happiness with various forms of luxury as well as desiring honor, other persons praise, and intellectual pleasures. But all of these pleasures are accompanied by the constant increased desire and the threat of boredom, a pain unknown to the brutes. Thought in particular creates a vast amount of passion, but in the end all of the struggling is for the same things that non-human animals attain—pleasure and pain. But humans, unlike the animals, are haunted by the constant specter of death, a realization which ultimately tips the scale in favor of being a brute. Furthermore, non-human animals are more content with mere existence, with the present moment, than are humans who constantly anticipate future joys and sorrows.

And yet animals suffer. What is the point of all their suffering? You cannot claim that it builds their souls or results from their free will. The only conclusion we should come to is “that the will to live, which underlies the whole world of phenomena, must, in their case satisfy its cravings by feeding upon itself.” Schopenhauer argues that this state of affairs—pointless evil—is consistent with the Hindu notion that Brahma created the world by a mistake, or with the Buddhist idea that the world resulted from a disturbance of the calm of nirvana, or even with the Greek notion of the world and gods resulting from fate. But the Christian idea that a god was happy with the creation of all this misery is unacceptable. Two things make it impossible for any rational person to believe the world was created by an omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent being: 1) the pervasiveness of evil; and 2) imperfection of human beings. Evil is an indictment of such a creator but since there is no such creator it is ultimately an indictment of reality and of ourselves.

Schopenhauer continues: “If you want a safe compass to guide you through life, and to banish all doubt as to the right way of looking at it, you cannot do better than accustom yourself to regard this world as a penitentiary, a sort of penal colony.” He claims this is the view of Origen, Empedocles, Pythagoras, Cicero, as well as Brahmanism and Buddhism. Human life is so full of misery that if there are invisible spirits they must have become human to atone for their crimes.

If you accustom yourself to this view of life you will regulate your expectations accordingly, and cease to look upon all its disagreeable incidents … as anything unusual or irregular; nay, you will find everything is as it should be, in a world where each of us pays the penalty of existence in [their] own particular way.

Ironically there is a benefit to this view of life; we no longer need look upon the foibles of our fellow men with surprise or indignation. Instead we ought to realize that these are our faults too, the faults of all humanity and reality. This should lead to pity for our fellow sufferers in life. Thinking of the world as a place of suffering where we all suffer together reminds us of “the tolerance, patience, regard, and love of neighbor, of which everyone stands in need, and which, therefore, every [person] owes to [their] fellows.”

Summary – Schopenhauer thinks life, both individually and as a whole, is meaningless, primarily because of the fact of suffering. It would be better if there was nothing. Given this situation, the best we can do is to extend mercy to our fellow sufferers.

______________________________________________________________________

Schopenhauer, “On the Sufferings of the World,” 54.

November 16, 2015

Nihilism

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

~ William Shakespeare

‘God’, ‘immortality of the soul’, ‘redemption’, ‘beyond’. Without exception, concepts to which I have never devoted any attention, or time; not even as a child. Perhaps I have never been childlike enough for them? I do not by any means know atheism as a result; even less as an event: It is a matter of course with me, from instinct. I am too inquisitive, too questionable, too exuberant to stand for any gross answer. God is a gross answer, an indelicacy against us thinkers—at bottom merely a gross prohibition for us: you shall not think!

~ Friedrich Nietzsche

Nihilism

Nihilism is the philosophical doctrine which denies the existence of one or more of those things thought to make life good such as knowledge, values, or meaning. A true nihilist does not believe that knowledge is possible, that anything is valuable, or that life has meaning. Nihilism also denotes a general mood of extreme despair or pessimism toward life in general.

The historical roots of contemporary nihilism are found in the ancient Greek thinkers such as Demosthenes, whose extreme skepticism concerning knowledge is connected with epistemological nihilism. But as historians of philosophy point out, many others including Ockham, Descartes, Fichte, and the German Romanticists contributed to the development of nihilism.The philosophy of Frederick Nietzsche is most often and most closely associated with nihilism, but it is not clear that Nietzsche was a nihilist. So we will begin our study of nihilism tomorrow with the philosopher who had the most influence upon Nietzsche, and who was definitely a nihilist, Arthur Schopenhauer.

________________________________________________________________________

Michael Allen Gillespie, Nihilism Before Nietzsche, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

November 15, 2015

1/2 A Million Views!

I started this blog less than two years ago and I started tracking page views about a year and a half ago. Today I just went over 500,000 page views. I also will publish my 500th post in the next few days.

I would like to thank my readers, many of whom have made insightful comments, and a few of whom I’ve come to know through email. Despite what they might say about writing for themselves, every writer also wants to be read. So again thanks to all who have viewed these pages.

Finally I have many plans to improve the website. I want to soon start video blogging, in large part so that when I’m gone my granddaughter can still hear my voice. I also want to explore the idea of hope and how it is, I think, the key that helps us to brave the struggle of life without appealing to dubious metaphysical propositions.

So if you like the site, you can be assured there is more coming. Thanks,

JGM