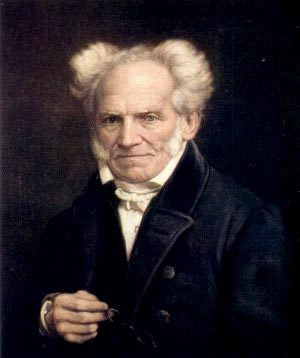

Summary of Arthur Schopenhauer’s, “On the Vanity of Existence””

In “On the Vanity of Existence,” Schopenhauer argues that life’s futility:

is revealed in the whole form existence assumes: in the infiniteness of time and space contrasted with the finiteness of the individual in both; in the fleeting present as the sole form in which actuality exists; in the contingency and relativity of all things; in continual becoming without being; in continual desire without satisfaction; in the continual frustration of striving of which life consists. Time and that perishability of all things existing in time that time itself brings about is simply the form under which the will to live, which as thing in itself is imperishable, reveals to itself the vanity of its striving. Time is that by virtue of which everything becomes nothingness in our hands and loses all real value.

The past is no longer real and thus “it exists as little as does that which has never been.” The present compares to the past as something does to nothing. We came from nothing after eons of time and will shortly return to nothing. Each moment of life is transitory and fleeting and quickly becomes the past—in other words, vanish into nothingness. The hourglass of our lives is slowly emptying. In response one might simply try to enjoy the present, but since the present so quickly becomes the past it “cannot be worth any serious effort.”

Existence rests in the fleeting present; it is thus always in motion, resembling “a man running down a mountain who would fall over if he tried to stop and can stay on his feet only by running on… Thus existence is typified by unrest.” Such a life is one of striving continually for what can seldom be attained or what, when attained, quickly disappoints. We live life hurrying toward the future but also regretting what is past—while the present we regard as merely the way to the future. When looking back on our lives we find that they were not really enjoyed, but instead experienced as merely the way to the future. Our lives were all those present moments that seemed so impossible to enjoy.

What is life then? It is a task where we strive to sustain our lives and avoid boredom says Schopenhauer. Such a life is a mistake:

Man is a compound of needs which are hard to satisfy; that their satisfaction achieves nothing but a painless condition in which he is only given over to boredom; and that boredom is a direct proof that existence is in itself valueless, for boredom is nothing other than the sensation of the emptiness of existence. For if life, in the desire for which our essence and existence consists, possessed in itself a positive value and real content, then there would be no such thing as boredom: mere existence would fulfill and satisfy us. As things are, we take no pleasure in existence except when we are striving after something—in which case distance and difficulties make our goal look as if it would satisfy us (an illusion which fades when we reach it)—or when engaged in purely intellectual activity, in which case we are really stepping out of life so as to regard it from outside, like spectators at a play. Even sensual pleasure itself consists in a continual striving and ceases as soon as its goal is reached. Whenever we are not involved in one or other of these things but directed back to existence itself we are overtaken by its worthlessness and vanity and this is the sensation called boredom.

That our will to live will eventually be extinguished is “nature’s unambiguous declaration that all the striving of this will is essentially vain. If it were something possessing value in itself, something which ought unconditionally to exist, it would not have non-being as its goal.” We begin our lives in the bodily desires of other persons and end as corpses.

And the road from the one to the other too goes, in regard to our well-being and enjoyment of life, steadily downhill: happily dreaming childhood, exultant youth, toil-filled years of manhood, infirm and often wretched old age, the torment of the last illness and finally the throes of death—does it not look as if existence were an error the consequences of which gradually grow more and more manifest?

Summary – The finitude of existence, the ephemeral nature of the present, the contingency of life, the non-existence of the past, the constancy of need, the experience of boredom, and, most importantly the inevitability of death, all lead to the conclusion that life is pointless.

_______________________________________________________________________

Schopenhauer, “On the Vanity of Existence,” 70.