John G. Messerly's Blog, page 103

November 14, 2015

Agnosticism Regarding the Meaning of Life

For the past ten days I have discussed various thinkers whom I’d classify as agnostic on the question of life’s meaning. I’d like to summarize and reflect on all of the now.

Edwards, Ayer, and Nielsen all advance the most basic reason to be skeptical of an answer to the question of the meaning of life—there cannot logically be an answer to it, insofar as there cannot be anything outside of everything to give life meaning. In response we pose two questions: 1) should we be confident that the ultimate why question cannot be answered; and 2) should we be confident that we need to answer this question? I propose that the answer to both is no.

Regarding the first question, the first reason to reject these authors’ conclusion is that we simply do not know whether the question is meaningless or meaningful, answerable or unanswerable. I am skeptical of the capacity of our minds to wrap themselves around this ultimate question, as our minds did not evolve to answer it. These authors may be correct that if it were impossible to answer a question then the question would be meaningless. But how can we know that it is impossible to answer the question? We cannot rule out all possible answers beforehand; we cannot even know all the possible answers. Thus we should draw no conclusions whatsoever about answers to the ultimate why question; in other words, we should be skeptical of skepticism.

A second reason to reject the view that the question is meaningless is found in the essay by Wisdom. His argument that the question is meaningful as well as possibly answerable is a strong one. I think he is correct; the question is meaningful. It is a relatively straightforward question even if we cannot answer it. There is nothing outrageous about asking what the whole thing means, with the caveat that that answer cannot come from outside of everything but must come from within everything.

A third reason to reject the claim that the question is meaningless has to do with our intuition. It is philosophically problematic to appeal in this way, but there would be something very strange and irrational about the world if such a universal question turned out to be baseless. Of course the nihilists will draw this exact conclusion but the counter-intuitive nature of the claim that the question is meaningless counts slightly against the claim. Putting all these reasons together, we have not been given sufficient rationale for concluding that our question is meaningless.

Turning to our second question—do we need to answer the question—Ayer’s claim that we can reduce our big question to littler ones is instructive. Perhaps we don’t need to answer the super ultimate why question; perhaps we need mostly concern ourselves with how we should live. After all we can know something about how to live without knowing everything about the universe. We may not know why there is something rather than nothing, but we know many things—what makes us happy or what we find worthwhile. In short this second question is more manageable. So we can say something about the meaning of life—how we should live given what we know about ourselves and the world—without having to say everything about the meaning of life.

Nielsen agrees that we cannot answer the ultimate why question and he also agrees with Ayer that the meaning question reduces to the question of what we find valuable. But he goes a bit further than Ayer’s appeal to subjective values, claiming that we can at least give reasons why we value one thing or another. Nevertheless, we cannot answer the question: what gives value to all things that is independent of human choices and attitudes? Thus we cannot ultimately ground value objectively outside of ourselves. Furthermore, if our values ultimately come from us asking for objective value or meaning invites despair and reveals our insecurity. We should be content with finding reasons for doing one thing rather than another, even if such a distinction is not based on objective values.

Given the above considerations it is not surprising that so many of our thinkers will turn to subjective value. For example Hepburn argues that the question is likely to be both meaningless and unanswerable objectively, forcing him to turn to subjective values as the only source of meaning. Like many of the thinkers we have examined, he sheds serious doubt that meaning can be grounded on some metaphysical or theological concerns. Thus Hepburn must reduce the abstract question of universal meaning to more concrete issues concerning subjective values. Nozick also rejects external meaning from the gods, leaving meaning to be found in subjective values. But Nozick goes further than Hepburn or Nielsen by considering that creating meaning may not really be enough. He asks: How can meaning exist at all, in any form? How can meaning, by itself, just shine? He hints that the answer to both questions is—it cannot. If he is correct we are left forlorn.

The pessimism hinted at by Nozick is picked up by Joske. While he agrees with Wisdom that the question is meaningful, there are multiple reasons why life is probably meaningless. What a depressing thought. No wonder that Joske thinks that philosophy is dangerous; it effectively removes all our moorings. If we combine Nozick’s concern that subjective values are not enough to satisfy our thirst for meaning with Joske’s radical skepticism about meaning in life, we are left with a skeptical cynicism regarding the very possibility of living a meaningful life. Hanfling suggests putting these questions out of our minds and just pretending or playing at life. But could we really sustain such an outlook? Would not existential concerns intrude in our merriment? Perhaps such questions motivate Wittgenstein to conclude that we might as well remain silent; remain skeptics; remain agnostics.

Since we cannot say that our question is definitely meaningless or unanswerable, we ought to be skeptical of those conclusions. Yet even if there cannot be an answer or we cannot know an answer to our big question, we can meaningful ask and propose answers to the queries: How should we live? And, what should we value? These questions are not overwhelming or unsolvable. Still, we remain deeply disturbed by Nozick’s insinuation that answers to these questions may not be enough, and by Joske’s implication that all may be for naught. And nothing Hanfling or Wittgenstein says comforts either. We don’t want to deceive ourselves and we don’t want to remain silent. In the end then it is not agnosticism that disturbs us, but the indication that it hints at something worse—at nihilism. What terrifies us is not that there is no answer or that we don’t know it. What terrifies is that there is an answer and that answer is that life is meaningless. It is to nihilism that we will now turn.

November 13, 2015

Wittgenstein on the Meaning of Life

Meaningless Question or Ineffable Answer?

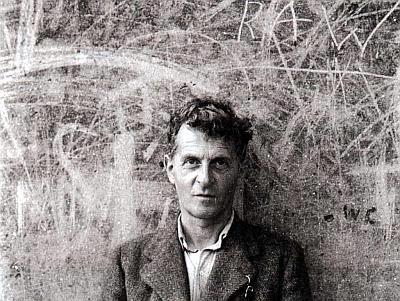

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (1889 –1951) was an Austrian philosopher who held the professorship in philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1939 until 1947. He first went to Cambridge in 1911 to study with Bertrand Russell who described him as: “the most perfect example I have known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.” Wittgenstein inspired two of the century’s primary philosophical movements, logical positivism and ordinary language philosophy, and is generally regarded as one of the two or three most important philosophers of the twentieth century.

Given his stature as a 20th century giant of philosophy, we would be remiss if we did not mention Wittgenstein’s doubt regarding the sensibility of the question of life’s meaning, with the caveat that his positions are notoriously difficult to pin down and that we cannot, in this short space, due justice to the depth of his thought. To get the briefest handle on his thought on the question of the meaning of life, we will ruminate briefly upon the haunting lines that conclude his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

For an answer which cannot be expressed the question too cannot be expressed. The riddle does not exist. If a question can be put at all, then it can also be answered. Skepticism is not irrefutable, but palpably senseless, if it would doubt where a question cannot be asked. For doubt can only exist where there is a question; a question only where there is an answer, and this only where something can be said. We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer. The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem.(Is not this the reason why men to whom after long doubting the sense of life became clear, could not then say wherein this sense consisted?) There is indeed the inexpressible. This shows itself; it is the mystical …Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

One problem with these famous lines is that they are open to at least two different interpretations. On one interpretation the question of the meaning of life lacks meaning; hence there is no answer to a meaningless question. Worries about the question end when we forget it and start living, but this is not the same as learning an answer—there is no answer to a meaningless question. On the other interpretation there is an answer to the question but we cannot say what it is—the answer is ineffable. If we take the question in the first way, then we no longer have to worry about it since there is nothing to know. If we take the question the second way, then we are somewhat comforted by the existence of a truth which cannot be spoken.

The problem is the tension between these two interpretations. How do we reconcile the claim that the question is meaningless with the claim that there is an ineffable answer? (One way to reconcile the two might be to say that the inexpressible only reveals itself after the question has disappeared.) However we interpret Wittgenstein’s enigmatic remarks, we can say this. If the question is senseless, then we waste our time trying to answer it; and if the answer is ineffable, then we waste our time trying to verbalize it. Either way there is nothing to say. Thus we probably ought to follow Wittgenstein’s advice and simply “be silent.” (l have obviously not follow his advice.)

__________________________________________________________________

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1922, trans. C.K. Ogden (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul). Originally published as “Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung”, in Annalen der Naturphilosophische, XIV (3/4), 1921.

November 12, 2015

Summary of Oswald Hanfling’s, The Quest for Meaning

Harmless Self-Deception

Oswald Hanfling (1927-2005) was born in Berlin but when his parents had their business vandalized on Kristallnacht in 1938, he was sent to England to live with a foster family. He left school at the age of 14 and for the next 25 years worked as a businessman. Bored, he returned to school eventually earning a PhD in 1971. Hanfling was appointed as a lecturer at the Open University in 1970 and worked there until retiring as a professor in 1993.

Hanfling’s book-length text, The Quest for Meaning (1987), begins by suggesting that our profound sounding question may admit of no answer. It is simply not clear what kind of answer we seek when we ask what the meaning of life or grass or an ocean is. A similar difficulty arises if we ask what purpose of life is.

(1987), begins by suggesting that our profound sounding question may admit of no answer. It is simply not clear what kind of answer we seek when we ask what the meaning of life or grass or an ocean is. A similar difficulty arises if we ask what purpose of life is.

Despite these worries Hanfling acknowledges that the notions of meaning and purpose regarding life arise in familiar ways. Depressed persons may say that their lives lack meaning, while others may say their lives are full of meaning. In either case we have a clear idea of what such persons mean. If someone says their life is meaningless they are telling us that something is wrong with it, that it is unsatisfactory, that it is somehow lacking. In addition people worry about the meaning of life as a whole too.

Hanfling devotes the first part of his book to aspects of life that may render it meaningless—general difficulties with the possibility of purpose, suffering, and death. He finds no conclusive argument that life is meaningless, but neither can he show that worries about meaninglessness are unfounded. The second part of the book considers the value of life and the possibility of finding meaning through self-realization. He is skeptical of the claim that life is valuable or that certain values are self-evident. Moreover, none of the arguments for self-realization are convincing, and no general prescription for the good life is available. The problem with trying to realize our nature is that we don’t know what our nature is or even if one, as Sartre and other existentialists suggest.

One possible solution is to put all these questions out of our minds by devoting ourselves to our jobs, social roles, or other prescriptions of our traditions. However, radical questioning may return and destroy this stasis by undermining our uncritical acceptance of our traditions. In response we might hold on tighter to our traditions by keeping questions out of our minds. But is putting these questions out of our minds self-deception? When a waiter plays the role of a waiter is that self-deception? How about actors who lose themselves in their roles? Hanfling argues that we are better off if we play at being a waiter, actor, or philosophy professor. This may be self-deception, but it is of the benign kind.

These considerations lead Hanfling to consider that just as being rational, social, intellectual, aesthetic, or moral may lead to self-realization, so too may play. Hanfling has in mind an attitude opposed to seriousness, the free expression in an activity of what we are. (We will see this echoed later in the piece by Schlick.) We play by treating supposedly serious concerns with a playful outlook. All of this leads to Hanfling’s conclusion:

The human propensity for playing, for finding meaning in play and for projecting the spirit of play into all kinds of activities, is a remedy for the existentialist’s anguish, and for the lack of an ultimate purpose of life or prescription for living. If we can deduce such prescriptions neither from a natural nor from a supernatural source … we can still help ourselves through the spirit of play, finding fulfillment in the playing of a role or in regarding what we do as a kind of game. This is a kind of self-deception, but it is not irrational or morally wrong. We are, rather, taking advantage of certain properties of man, of Homo ludens, which make life more satisfying than it would otherwise be.

Summary – While the question of the meaning of life may not make sense and there are no general answers, we will live better if we benignly deceive ourselves and play as if there is meaning to our lives.

_________________________________________________________________

Oswald Hanfling, A Quest for Meaning (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987), 214.

November 11, 2015

Summary of W.D. Joske’s, “Philosophy and the Meaning of Life”

A Meaningful Question: A Meaningless Life

W.D. Joske (1928- 2006) was a professor of philosophy at the University of Tasmania in Australia. In his 1974 article “Philosophy and the Meaning of Life,” he notes that ordinary people often assume that philosophers think deeply about the meaning of life and related problems. Consequently they fear philosophy because they think it leads to the conclusion that life is meaningless. A typical response from professional philosophers is that this fear is unfounded since life “cannot be shown to be either significant or insignificant by philosophy.” But Joske argues that this view is mistaken and that one should indeed be afraid of philosophy. It may have something disconcerting to say about the meaning of life after all.

Joske claims that the question of the meaning of life is both vague (its meaning is unclear) and ambiguous (it has many meanings.) The questioner may be asking the meaning of: 1) all life; 2) human life; or 3) an individual life. Joske addresses this second issue only, not concerning himself with questions about the significance of history of Homo sapiens, but rather with the question of “whether or not the typical human life style can be given significance.” And what makes an activity significant or meaningful? Meaningful activities are ones with significance and that significance can be either intrinsic—from the activity itself—or derivative—from the end toward which that activity leads. Individuals want their activities to have both kinds of significance.

Yet, Joske argues, even if there is an objective end for humans that end will have meaning for us only if we make it our own. It follows that the meaning of life is not to be discovered in an indifferent world, but must be provided or created by individuals. People who seek meaning in objective facts about the world are confused. The world is unsympathetic to us; it is neither meaningful nor meaningless—it just is. Yet Joske rejects this solution as facile and unsatisfying. The question of the meaning of life is a deep and real one which the simple injunction to create meaning does not adequately answer.

Joske proceeds to claim “that life may be meaningless for reasons other than that it does not contribute to a worthwhile goal, so that the failure to find meaning in life can be due to the nature of the world and not simply to failure of adequate commitment by an agent.” In other words, as opposed to the view of the optimists, the world may be intrinsically and deeply meaningless. Life may be like an activity but its significance can be challenged on many grounds. Joske labels four elements of meaninglessness: worthlessness, pointlessness, triviality, and futility. Activities can be: 1) worthless—lack intrinsic merit as in mere drudgery; 2) pointless—not directed toward any end; 3) trivial—have an insignificant end; or 4) futile—the end cannot be achieved. So activities lack meaning if they are worthless, pointless, trivial, or futile. At one extreme activities are fully meaningful if they lack none of these, that is, if they are intrinsically valuable, directed toward a non-trivial end, and not futile. At the other extreme, actions are fully valueless or meaningless if the lack all four element of meaning. In between are activities that are partially valuable. Joske says that most of us can never rid ourselves of the view that everything may be futile; and the few who do not think about this are lucky.

Joske now turns to showing how commonly held views lead to the conclusion that life is futile. To explain he clarifies what he means by “the typical human life style.” While there is much diversity among human cultures and peoples, humans share certain traits such as being rationally reflective and having biological dispositions. So he wonders if we can assess the typical human lifestyle like we can assess activities. The main difference between them is that this core human nature is a given whereas we make choices about our activities. Notwithstanding this Joske thinks there are enough similarities so that we can assess the meaning of life by using the same criteria of judgment we use for activities. Judgments about pointlessness, futility, triviality, and worthiness are applicable to lives. Are there then any commonly held views about the world which would then lead us to view life as meaningless? Joske thinks there are.

CASE 1 – The Naked Ape – Many of our most supposedly noble endeavors are reducible to biology. Much of what we think we choose has been determined by our evolutionary history.

CASE 2 – Moral Subjectivism – Many of our moral choices are futile in the face of the world. With no objective moral reality much of what we do is futile.

CASE 3 – Ultimate Contingency– The reason for the laws of nature themselves is without reason, they are ultimately coincidences. There is no reason for what we call laws of nature; reality is not rational.

CASE 4 – Atheism– The gods have been thought to ground objective morality. Joske objects that gods and morality cannot be adequately connected, given Plato’s famous question. (Is something right because the gods command it; or do the gods command it because it’s right?)

Moreover, the purpose of the gods does not seem to give our lives meaning unless they become our own; and many find the idea that they can only find meaning in a god’s plan degrading, as if man is an instrument for someone else’s amusement. Nonetheless, many still feel that life without gods is meaningless. This is partly because people are indoctrinated to think this, yet Joske concedes that non-belief opens up another level of absurdity. While religious belief denies that life is futile, the non-believer has no such guarantee.

The point of all this is to show that philosophy is not neutral on the question of the meaning of life. It is also to show that there are analogies between futile activities—digging ditches and then filling them—and many things that people actually do as part of a human life. Examples of such futility include: Thinking our actions are noble when they are biologically motivated; dying for a cause which is ultimately unimportant; acting as if things are rational when in fact they are not; believing the gods give meaning when they do not do so or do not exist.

So what now? First Joske says that although we should not reject philosophical views that challenge our view of meaning, we may still question those views since the reasoning which led to them may have been unsound. Second “the futility of human life does not warrant too profound a pessimism. An activity may be valuable even though not fully meaningful…” Although life may be futile—our ultimate ends cannot be achieved—we can still value them and give them our own meaning. However, this is not enough for Joske. If we cannot really be fulfilled, if our ultimate ends cannot really be achieved, life becomes grim. “A philosopher, even though he enjoys living, is entitled to feel some resentment towards a world in which the goals that he must seek are forever unattainable.”

Summary –The question of the meaning of life is both meaningful and dangerous. It is hard to rid ourselves of the view that life may be meaningless because of considerations related to biology, moral subjectivism, and a contingent, irrational and non-theistic metaphysics. We can try to value our lives, but we are justified in being dissatisfied with a life which might ultimately be futile and meaningless.

____________________________________________________________________

Joske, “Philosophy and the Meaning of Life,” 294.

November 10, 2015

Robert Nozick on the Meaning of Life

How Can Anything Glow Meaning?

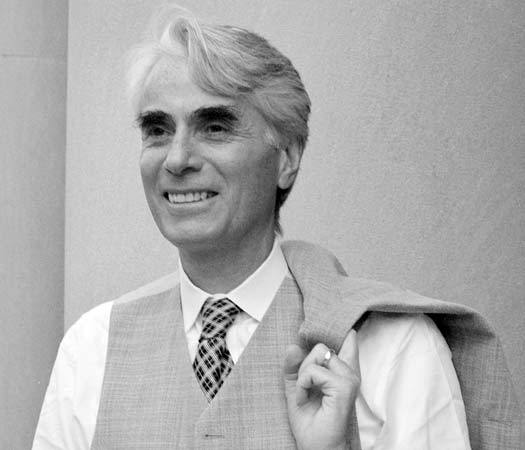

Robert Nozick (1938 – 2002) was an American political philosopher and professor at Harvard University. He is best known for his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia , a libertarian answer to John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice . In chapter six of his 1981 book, Philosophical Explanations

, a libertarian answer to John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice . In chapter six of his 1981 book, Philosophical Explanations , Nozick addresses the question of the meaning of life.

, Nozick addresses the question of the meaning of life.

“The question of what meaning our life has, or can have, is of utmost significance to us.” Yet we try to hide our concern about the question by making jokes about it. So what do we seek when asking this question? Basically we want to know how to live in order to achieve meaning. We may choose to continue our present life in the suburbs, change our lives completely by moving to a cave and meditating daily, or opt for a number of other possibilities. But how is one to know which life is really most meaningful from an infinite number of choices? “Could any formula answer the question satisfactorily?”

A formula might be the meaning of life: seek union with a god, be productive, search for meaning, find love, etc. Nozick finds none of the proposed formulas satisfactory. Do we then seek some secret verbal formula or doctrine? Suppose there were a secret formula possessed by the sages. Would they give it to you? Would you be able to understand it? Maybe the sage will give you a ridiculous answer just to get you thinking. Perhaps it is not words at all but the physical presence of the sage that will convey the truth the questioner seeks. By being in their presence over time you may come to understand the meaning of life even if meaning transcends verbal formulas. Nozick doubts all of this.

Now what about the idea that the meaning of life is connected with a god’s will, design or plan? In this case the meaning of life is to fulfill the role the gods have fashioned for us. If we were designed and created for a purpose connected to a plan then that is what we are for—our purpose would be to fulfill that plan. Different theological variants of your purpose might be to merge with the gods or enjoy eternal bliss in their presence.

Now let us suppose there are gods, that they have created us for a purpose, and that we can know that purpose. The question is, even knowing that all of the above is true, how does this provide meaning for our lives? Suppose for example that our role in the divine plan was trivial. Say it was to provide CO2 for plants. Would that be enough? No, you probably think your role needs to be more important than that. Not just any role will do, especially not a trivial one.

Moreover, we want our role to “be positive, perhaps even exalted.” We don’t want our role to be providing food for space aliens, however good we taste to them. Instead we want our role to focus on important aspects of ourselves like our intelligence or morality. But even supposing that we were to aid the space aliens by exercising our intelligence and morality that would not give us meaning if there was no point to us helping them. We want there to be a point to the whole thing.

Nozick argues that there are two ways we could be part of or fulfill a god’s plan: 1) by acting in a certain way; or 2) by acting in any way whatsoever. Concerning the first we may wonder why we should fulfill the plan, and about both we may wonder how being a part of the plan gives our lives meaning. It may be good from the god’s perspective that we carry out their plans, but how does that show it is good for us, since we might be sacrificed for some greater good? And even if it were good for us to fulfill their plan how does that provide us meaning? We might think it good to say help our neighbors and still doubt that life has meaning. So again how do the god’s purposes give our lives meaning? Merely playing a role or fulfilling a purpose in someone else’s plan does not give your life meaning. If that were the case your parent’s plan for you would be enough to give your life meaning. So in addition to having a purpose, the purpose must be meaningful. And how do a god’s purposes guarantee meaning? Nozick does not see how they could.

Accordingly you can: 1) accept meaninglessness, and either go on with your life or end it; 2) discover meaning; or 3) create meaning. Nozick claims 1 has limited appeal, 2 is impossible, so we are left with 3. You can create meaning by fitting into some larger purpose but, if you do not think there is any such purpose, you can seek meaning in some creative activity that you find intrinsically valuable. Engaged in such creative work, worries about meaninglessness might evaporate. But soon concerns about meaning return, when you wonder whether your creative activity has purpose. Might even the exercise of my powers be ultimately pointless? (This sends a chill through someone writing a book.)

Now suppose my creation, for example a book on the meaning of life, fits into my larger plan, to share my discoveries with others or leave something to my children. Does this give my creative activity meaning? Nozick doubts this solution will work since the argument is circular. That is, my creative activity is given meaning by my larger plan which in turn has meaning because of my creative activity. Moreover, what is the point of the larger plan? It was only chosen to give a meaning to life, but that does not show us what the plan is or what it should be.

This all brings Nozick back to the question of how our meaning connects to a god’s purposes. If it is important that our lives have meaning, then maybe the god’s lives are made meaningful by providing our lives with meaning, and our lives made meaningful by fitting into the god’s plans. But if we and the gods can find meaning together, then why can’t two people find it similarly? If they can then we do not need gods for meaning. Nor does it help to say that knowing the god’s plan will give life meaning. First of all many religions say it impossible to know a god’s plans, and even if we did know the plan this still does not show that the plan is meaningful. Just because a god created the world does not mean the purpose for creating it was meaningful, anymore than animals created by scientists in the future would necessarily have meaningful lives. It might be that directly experiencing a god would resolve all doubts about meaning. But still how can a god ground meaning? How can we encounter meaning? How can all questions about meaning end? “How, in the world (or out of it) can there be something whose nature contains meaning, something which just glows meaning?”

Summary – A god’s purposes do not guarantee meaning for you. Rather than accept meaninglessness or try to discover meaning, Nozick counsels us to create meaning. Still, this might not be enough to really give our lives meaning. In the end, does anything emanate meaning? Can anything glow meaning? Nozick is skeptical.

________________________________________________________________

Nozick, “Philosophy and the Meaning of Life,” 230.

November 9, 2015

Summary of R. W. Hepburn’s, “Questions about the meaning of life”

Unanswerable Question and Worthwhile Projects

R. W. Hepburn (1927-2008) grew up in Aberdeen Scotland and was Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. In his 1965 essay “Questions about the meaning of life,” Hepburn claims that traditionally the question of the meaning of life tends to be conjoined with metaphysical, theological, and/or moral claims—that the gods have a plan; that the cosmos has a goal; that justice reigns, that death must be overcome, etc. What then is an analytic or naturalistic philosopher to do? Typically they argue either we: a) cannot talk intelligently about meaning of life; or b) must talk about meaning in a completely different way from the traditional way to make sense out of the question. Hepburn opts for the latter.

Hepburn asserts that meaningful lives are purposeful, or pursue valuable ends. This implies that meaning is not found but created—we must make value judgments—and this holds whether or not there are cosmic trends or a cosmic order. Moreover, the claim that there are gods is just a claim about the facts and nothing follows from that about what ought to be valued. So nothing about meaning follows from the truth or falsity of religion.

If we switch the question from what is the meaning of life to what is its purpose we encounter two problems. First the idea of the purpose of life presupposes a single purpose, whereas there are multiple purposes for a human life; and second the question suggests that we are a mere artifact, tool, or instrument. Second the issue is problematic because it is incompatible with moral autonomy, since on this account we simply are something to be used. Thus there are two reasons to disconnect questions about meaning from metaphysical and theological claims. First such claims are about facts only and not about values; and second if a life is given meaning by its role as divine artifact, this denies moral autonomy.

Additionally, two other thoughts lead to the separation of metaphysics from meaning. First, if we consider the familiar claim that life is meaningless if death is the end, then we see the irrelevance of metaphysics to our question. There is no obvious connection between finitude and disvalue or between infinity and value. Flowers that die have value while an eternity of meaninglessness is a plausible notion. Thus metaphysical concerns about death do not straightforwardly connect to meaning questions. And second the quest for meaning is often thought of as the possession of some esoteric metaphysical or theological knowledge. Tolstoy thought that peasants had such knowledge insofar as they were not generally as depressed as intellectuals. As a rejoinder Flew pointed out that this does not mean the simple-minded possess some knowledge that Tolstoy did not, but rather that they possess some peace of mind that Tolstoy lacked. Hepburn agrees with this line of thinking which suggests that the answer to our query is not metaphysical but psychological or ethical. All these considerations weigh against the argument that meaning connects with metaphysical or theological claims.

Furthermore, if we consider Tolstoy’s or John Stuart Mill’s crisis of meaning we see that pursuing worthwhile projects is not enough for meaning either. We may think our projects valuable while still doubting they give our lives meaning. According to Hepburn finding meaning is not merely justifying our projects—we work to feed our children—but being energized and fulfilled by our projects. He contends that meaningful lives fuse these concerns; they pursue (morally) worthwhile projects that satisfy us. But it is not egoistic to want one’s worthwhile projects to be compelling or interesting. In fact we often judge lives to be less meaningful because they fail to be morally worthwhile or personally compelling.

The foregoing considerations lead Hepburn to conclude: “The pursuit of meaning … is a sophisticated activity, involving a discipline of attention and imagination.” What then of Tolstoy’s peasants? Hepburn argues that they possessed a weak sense of knowing how to live. They had not mastered techniques to deal with depression—they were not depressed—rather they were unaware of the kind of thoughts a Tolstoy or Mill might have. They knew how to live like babies know how to cry. But this weak sense of meaning is not enough if we see meaning as a problem that demands a reply. In that case we demand a stronger response to the question of how to live than the peasants gave; a response to the problematic context of life’s difficulties and possible means of overcoming them.

All of this raises an interesting question: “Could a man’s life have or fail to have meaning, without his knowing that it did or did not have meaning?” On the one hand, Hepburn contends that lives could be meaningful without the people living those lives being aware of their meaning—for example if they did not realize the valuable contributions they made. On the other hand, it is odd to say that someone did not know the meaning of their life but that a biographer would discover it later. Regarding those who are “unreflectively happy or unhappy, it would be most natural to say that they have neither found nor failed to find the meaning of life.” Tolstoy’s peasants are of the unreflective type, they have not found the meaning of life because they have never seen it as problematic; whereas if Tolstoy achieved their peace of mind he could be said to have found meaning, as he was aware of the problematic elements of life. Therefore those who have never been troubled by life’s difficulties cannot be said to have solved a problem.

What is particularly difficult to reconcile with meaning is death. Some, like Tolstoy, believe that without immortality there is no meaning; others claim that death or immortality are irrelevant to meaning. Hepburn argues that though mortality and meaning may be compatible, one may still be troubled by the thought that death detracts from meaning. More generally we might be troubled that the effort we put forth in life is so great compared with the effect of our lives. (Yeats captured this thought: “When I think of all the books I have read, wise words heard, anxieties given to parents … my own life seems to me a preparation for something that never happens.”)

Hepburn states that disappointment in life might take one of two forms. From an external standpoint an observer of your life would be disappointed that you did not fulfill your promise—in Hepburn’s analogy they expected a symphony but only witnessed an overture—or from an internal perspective you might be disappointed in yourself, that you did not produce the music you wanted to. Philosophers sometimes argue that you should not be disappointed. Even if you are not immortal, even if you do not write a great symphony, a short piece of music has value nonetheless. Better not to worry about your shortcomings; better to enjoy a life and its small accomplishments. But what of endless suffering leading to death? Does this not make life futile and meaningless? Hepburn claims that some lives may afford the possibility of meaning, while others may not.

He also recognizes a fundamental difference between the naturalist and the theist. The naturalist will always find a tension between a subjective anthropocentric view in which a life can have meaning, and the objective sub species aeternitatis view from where it is hard to see meaning. For the theist there is a harmony between meaning in human life and eternal meaning. Without such harmony, the theist claims, there cannot be meaning in life.

Throughout his discussion Hepburn assumed that Christian theism provides a satisfactory answer to the meaning of life question. But now he notes two challenges to this view: 1) that no afterlife could compensate for the suffering in this world or, using the musical analogy, if the overture was bad enough no music that followed could compensate; and 2) that there it is morally objectionable that a god’s plan give life meaning inasmuch as this conflicts with moral autonomy.

Hepburn regards this second objection as particularly strong. If the otherness and power of a god is stressed, then human moral judgment will be trivial compared to divine purpose. Nonetheless worshipping a god does not have to entail the abandonment of moral autonomy; it could be directed to the moral perfection and beauty of a god, and to actively internalizing that perfection as far as possible. So worshipping need not abrogate moral autonomy, and neither does acting in accord with what one believes is a god’s will. All one needs are good reasons to believe that following a god’s will is a better way to achieve some good than transgressing that will. Of course none of this shows that there are gods; that they have qualities one ought to worship; that these qualities are internally consistent or consistent with the world; that infinite gods have finite qualities; or that we could know their will. Thus the problem with the theistic conception of meaning is all of the difficulties with the plausibility of theism itself.

By contrast naturalistic philosophers seek a substitute for the immortality that gives the theist meaning. Rejecting religious metaphysics they try to find meaning only in beliefs they accept. This leaves naturalists open to the disturbing prospect that life may have no comprehensive, discoverable, or possible meaning. Hepburn concludes that we should consider the more limited notion of meaning—that there can be subjective purposes and better ways of living.

Summary – Hepburn maintains that theological and metaphysical realities are of little help in answering meaning questions. Instead we should focus on worthwhile projects that we find satisfying and interesting. We probably cannot answer the question of the meaning of life from a comprehensive, external point of view, but we can try to live as well as possible.

_____________________________________________________________________

Hepburn, “Questions about the meaning of life,” 268.

November 8, 2015

Summary of John Wisdom’s, “The Meanings of the Questions of Life”

A Meaningful but Mostly Unanswerable Question

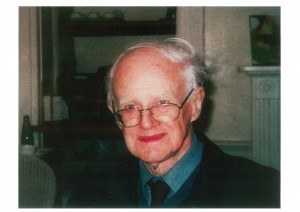

Not all philosophers agree that the ultimate why question is meaningless. A notable exception was John Wisdom (1904–1993), who spent most of his career at Trinity College, Cambridge, and became Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge University.

In his article 1965, “The Meanings of the Questions of Life,” Wisdom asks why some people think the question of the meaning of life is senseless. Because, he argues, answers to why questions appear to go on infinitely. (For example, if we ask what holds up the world and are told that it rests on a giant turtle, we may ask, what holds up the turtle? And if the answer we are given to that question is “super turtle,” we can then ask, what holds that up? And if we are told the answer to that question is “super duper turtle,” well, it is easy to see that we can just keep asking these questions forever and never resolve the issue.) Asking what supports everything is absurd and non-sensible; there cannot by definition be something outside of everything which supports everything. In short, there cannot be an answer to the ultimate why question.

Perhaps the meaning of life question cannot be answered because it asks for the why of everything rather than of just of a specific thing. Just because some particular thing supports some other particular thing does not mean that something supports everything. Similarly we can say that there is a meaning of something, but that does not mean there is a meaning for everything. Perhaps the meaning of life question is like this. If I tell you why I think something is meaningful, I always refer to something else and you can always ask: but why is that meaningful? So maybe the question of the meaning of life is like asking, what is the largest number? Or what supports everything? These all look for something outside everything but nothing is outside everything. Similarly, there cannot be a big meaning outside all the little inside meanings. (Essentially, this was the argument given by Edwards, Ayer, and Nielsen.)

So when we ask about the meaning of life we are asking about the meaning of the whole thing. And though there cannot be anything other than the whole thing, the question of what the whole thing means is not absurd. It’s like coming in in the middle of a movie and not seeing the end. In that case, we want to know what went before and after to make sense of it. We want to go outside of our experienced meaning to see the whole. But we might have seen the whole movie and still not know the meaning. In that case we might ask, what did the whole thing mean? And that is not an absurd question. We might ask whether the play or movie is a tragedy, comedy, or farce. It is a tough question but it is not senseless. From an eternal perspective I could sensibly ask: what does it all mean?

Of course, we have only seen a small part of the movie or of life; we do not know much about what went before and what will come after. Nonetheless we want to know what the whole thing means; in Wisdom’s words we are trying to find “the order in the drama of Time.” We don’t know the answer but the question is sensible, and we may move toward an answer as we learn more. An answer, if there is one, lies not outside but within the complex whole that is life.

Summary – The question of the meaning of everything makes sense. There cannot by definition be anything outside of everything that gives it meaning, since there is nothing outside of everything, but we can still meaningfully ask: what does the whole thing mean? That question may be unanswerable, but if there is an answer it comes from within life.

_____________________________________________________________________

John Wisdom, “The Meanings of the Questions of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 220-222.

November 7, 2015

Summary of Kai Nielsen’s,“Linguistic Philosophy and The Meaning of Life”

A Meaningless Question and Valuable Lives

Kai Nielsen (1926- ) is professor emeritus of philosophy at the University of Calgary. Before moving to Canada, Nielsen taught for many years at New York University (NYU). He is a prolific writer, the author of more than 30 books and 400 articles.

In his 1964 article, “Linguistic Philosophy and The Meaning of Life” Nielsen begins by agreeing with Ayer that the purpose of life is the end at which all things aim. The trouble with this answer, as Ayer pointed, is that it only explains existence—but we want more. We want the end to be something we chose, not something dictated from the outside. In short when we ask what the meaning of life is we don’t want an explanation of how things are; we want a justification of why things are. And no matter how completely we explain the facts about the world that does not tell us how we should live and die, it never tells us the meaning of it all.

Nielsen offers the example of discovering all sorts of facts about yourself. If after all this discovering you decide to continue to live as you had before, who can justifiably say that you are mistaken? No one is justified in saying that because all of these facts don’t imply any values about how to live.

Now suppose we add a god. Even if we assume there are gods, that they have purposes for us, and that we know these purposes, this still does not provide meaning for our lives. Why? Because either we have to be part of that plan or we don’t. If we have to be part of some god’s plan then these purposes would be the god’s purposes not ours, since the gods chose them and we did not. But if we do not have to be part of some god’s purpose then we must judge if a god’s plans are valuable, we must be the judge of whether to conform to the plan or not. So when we ask “what is the meaning of life?” we are not asking what our purpose is as a divine artifact. We don’t want to know what we were made for, or that we were constructed for something which may or may not have value. We want to know if there is something within our lives that gives us purpose, we want to know why we should live one way instead of another. And whether there are gods with plans for us or whether there are some ends built into us by nature, these facts don’t tell us how to live and die, they don’t tell us the meaning of it all. Only we can decide this for ourselves.

So far Nielsen agrees with Ayer’s analysis. But while Ayer concluded that we cannot reason about how to live, that value judgments are subjective, Nielsen argues that we can and do reason about morality—we do give reasons for saying one ought to do x or that x is good. But more importantly, Nielsen suggests that when we ask about meaning we really are asking for more than an answer to questions about what we ought to do or seek or value. Instead we are asking whether what we do matters at all. We are asking “Does anything matter?” But how do we answer such a question? If I say that love, conversation, and hiking are worthwhile to me, that they matter to me, I don’t seem to really have answered the question. We want to know if these things are really worthwhile, that they ever really matter in some ultimate way.

But does it make sense to ask if anything is really worthwhile? For this question to be intelligible we need some standard of worthiness outside of our subjective preferences. Suppose for example that the standard for a worthwhile life is whether or not that life brings about the elimination of all human suffering. In that case one might legitimately say that life is worthless since nothing one does will likely achieve that goal. Such a criterion for worthiness is unrealistic. In contrast Nielsen argues that something is worthwhile not only if it ought to be achieved, but also that it can be achieved. If the goal cannot be achieved—eliminating all human suffering—one is bound to be frustrated, which means that one has set the bar too high. Instead we should set the bar more realistically by making our purpose, for example, to “help alleviate the sum total of human suffering.” This realistic goal is more conducive to our finding meaning. Often the frustration one feels from not being able to do more leads to questions about meaning. In this case we can probably not understand all suffering much less eliminate it, but we can find meaning by fighting against it. In short Nielsen counsels us to adopt the attitude that some things are valuable.

So what things are of value? Going to art museums or on fishing trips is valuable if you like art and fishing. And to say that such things are not eternal does not detract from their meaning. In fact it might add to it, since an eternity of doing these things would be boring. If we seek a more general answer to the question of why anything is worthwhile we might answer that people’s preferences, desires, and interests are the cause of them finding certain things worthwhile. The reason certain things are worthwhile depends on the thing in question. So questions about the meaning of life do ultimately reduce to questions about ends that are worthwhile—we do find worthwhile what we desire, approve of, or admire. This may seem unsatisfactory, but all we can do is show that questions about what is meaningful or worthwhile are intelligible; they are amenable to general answers. If we value things, they are worthwhile to us.

But what if someone still wants an objective answer to the meaning of life question, an answer that is independent of a particular person’s values? Nielsen argues that this question cannot be answered. There simply cannot logically be something that gives meaning to everything else but which is independent of human values. One way of understanding this point is to consider questions like “how hot is blue?” or “what holds the universe up?” These have the grammatical form of intelligible questions, but they are not intelligible. We can answer why certain things are valuable but the question of why things as a whole are valuable is non-sensible. Nielsen argues that if you continue to ask the meaning of life question after you have been told about subjective values, you will never be satisfied and something may be psychologically wrong with you. You may simply be expressing your own anxiety or insecurity.

Summary – We cannot know the answer to the question, why anything. As for the meaning of life, it is more than a question about what is valuable; it asks whether anything is valuable or anything matters. We might say that nothing matters since our efforts to effect change come to so little, but we should find meaning in the little we can do. Thus meaning reduces to subjective ends that we find worthwhile.

______________________________________________________________________

Kai Nielsen, “Linguistic” Philosophy and “The Meaning of Life,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 211.

November 6, 2015

Summary of A. J. Ayer’s,”“The Claims of Philosophy”

A Meaningless Question and Subjective Values

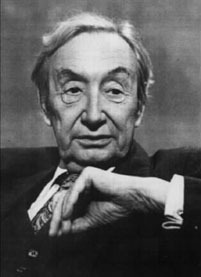

A.J. Ayer (1910 – 1989) was the Grote Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College London from 1946 until 1959, when he became Wykeham Professor of Logic at the University of Oxford. He is one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth-century. Ayer is perhaps best known for advocating the verification principle, the idea that statements and questions are meaningful only if we can determine whether they are true by analytic or empirical methods.

In his 1947 article “The Claims of Philosophy,” Ayer asks: does our existence have a purpose? According to Ayer to have a purpose means to intend, in some situation “to bring about some further situation which … he [she] conceives desirable.” (For example, I have a purpose if I intend to go to law school because that leads to becoming a lawyer which is something I consider desirable.) Thus events have or lack meaning to the extent they bring about, or do not bring about, the end that is desired. But how does “life in general” have meaning or purpose? The above suggests that overall meaning would be found in the end to which all events are tending. Ayer objects that: 1) there is no reason to think that there is an end toward which all things are tending; and 2) even if there were such an end it would do us no good in our quest for meaning because the end would only explain existence (it is heading toward some end) not justify existence (it should move toward that end). Furthermore, the end would not have been one we had chosen; to us this end is arbitrary, that is, it is without reason or justification. So from our point of view, it does not matter whether we receive a mechanical explanation (the end is universal destruction) or a teleological explanation (the end is union with a god). Either way we merely explain how things are but we do not justify why things are—and that is what we want to know when we ask the meaning of life question. We want to know if there is an answer to this ultimate why question.

Now one might answer that the end toward which all is tending is the purpose of a superior being and that our purpose or meaning is to be a part of the superior being’s purpose. Ayer objects that: 1) there is no reason to think that superior beings exist; and 2) even if there were superior beings it would do us no good in our quest for meaning because their purposes would not be our purposes. Moreover, even if superior beings had purposes for us, how could we know them? Some might claim this has been mysteriously revealed to them but how can they know this revelation is legitimate? Furthermore, allowing that superior beings have a plan for us and we can know it, this is still not enough. For either the plan is absolute—everything that happens is part of the plan—or it is not. If it is absolute then nothing we can do will change the outcome, and there is no point in deciding to be part of the plan because by necessity we will fulfill our role in bringing about the superior being’s end. But if the plan is not absolute and the outcome may be changed by our choices, then we have to judge whether to be part of the plan. “But that means that the significance of our behavior depends finally upon our own judgments of value; and the concurrence of a deity then becomes superfluous.”

Thus invoking a deity does not explain the why of things; it merely pushes the why question to another level. In short even if there are deities and our purpose is to be found in the purposes they have for us, that still does not answer questions such as: why do they have these purposes for us? Why should we choose to act in accord with their plans? And regarding the answers to these questions we can simply ask why again. No matter what level of explanation we proceed to, we have merely explained how things are but not why they are. So the ultimate why question—why does anything at all exist—is unanswerable. “For to ask this is to assume that there can be a reason for our living as we do which is somehow more profound than any mere explanation of the facts…” So it is not that life has no meaning. Rather it is the case that it is logically impossible to answer the question—since any answer to why always leads to another why. This leads Ayer to conclude that the question is not factually significant.

However, there is a sense in which life can have meaning; it can have the meaning or purpose we choose to give it by the ends which we choose to pursue. And since most persons pursue many different ends over the course of their lives there does not appear to be any one thing that is the meaning of life. Still, many search for the best end or purpose to pursue, hence the question of meaning is closely related to, or even collapses into, the question: how should we live? But that issue cannot be resolved objectively since questions of value are subjective. In the end each individual must choose for themselves what to value; they must choose what purposes or ends to serve; they must create meaning for themselves.

Summary – There is no reason to think there is a purpose or final end for all life and even if there were one, say it was to fulfill a god’s purpose, that would be irrelevant since that purpose would not be ours. Regarding such a plan either we cannot help but be part of it—in which case it does not matter what we do—or we must choose whether to be part of it—which means meaning is found in our own choices and values. Moreover, all this leads us to ask what is the purpose or meaning of the gods’ plans; but any answer to that question simply begets further why questions indefinitely. Thus it is logically impossible to answer the ultimate why question. In the end, the question of the meaning of life dissolves into or reduces to the question of how we should live.

A. J. Ayer, “The Claims of Philosophy,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke and Steven Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 199.

Ayer, “The Claims of Philosophy,” 200.

Ayer, “The Claims of Philosophy,” 201.

November 5, 2015

Summary of Paul Edwards’ “Why?”

A Meaningless Question

Paul Edwards (1923 – 2004) was an Austrian American moral philosopher who was editor-in-chief of Macmillan’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy, published in 1967. With eight volumes and nearly 1,500 entries by over 500 contributors it is one of the monumental works of twentieth century philosophy.

In his 1967 article entitled “Why,” Edwards discusses whether or not the question of the meaning of life is itself meaningful. He begins by pondering two issues regarding the use of the word why: 1) the contrast between how and why questions, and the prevalent view that science only deals with how questions; and 2) ultimate or cosmic why questions like “Why does anything at all exist?” or “Why is there something rather than nothing?”

Regarding the first issue, some thinkers insist on the contrast between how and why for religious or metaphysical reasons—maintaining that science answers how questions but only religion or metaphysics answers why questions. Other writers like Hume who are hostile to metaphysics, maintain that neither science, religion, nor metaphysics can answer why questions. Both groups agree that there are classes of meaningful why questions which cannot be answered by science; they disagree in that the former argue that religion or metaphysics can answer such questions, while the latter argue that they cannot be answered at all. In response Edwards makes a number of points. First, how and why questions are sometimes of the same type, as in cases where A causes B but we are ignorant of the mechanism by which it does this. In such cases it would be roughly equivalent to ask, why or how a particular drug works, or why or how some people who smoke get lung cancer but others do not. In these instances, science adequately deals with both why and how.

Still, there are cases when how and why ask different kinds of questions, as when we consider intentional human activity. How we robbed a bank is very different from why we robbed it, but it is false that empirical methods cannot answer both questions. In fact, the robbers probably know why they robbed the bank. True they might be lying or self-deceived about their aims, but still the answer is open to empirical methods. So we might ask the robbers friends about them or consult their psychoanalyst to find out why they did it.

For another case in which how and why questions differ, consider how we contrast questions about states or conditions as in “How cold is it?” or “How is his pain?” with questions about the causes of those conditions as in “Why is it cold?” or “Why is he in pain?” Clearly these are different types of questions. Edwards also notes that why questions are not always questions about the purposes of human or supernatural beings. To ask “Why are New York winters colder than Los Angeles winters?” is not necessarily to suppose that there is some conscious plan behind these phenomena. But it does appear we often answer both how and why questions without resorting to metaphysics.

To summarize Edwards thus far: how and why often are used to ask the same question; when dealing with human intentional actions they ask different questions—how asking about the means, why asking about the ends. Additionally, how questions often inquire about states or conditions, while why questions inquire as to the causes of those states or conditions. It does seem that we can in principle answer all these questions without resorting to religion or metaphysics.

Regarding our second issue, cosmic why questions, Edwards begins by considering what he calls “the theological why.” The theological answer to the theological why posits that a god answers the question of meaning. Major difficulties here include how we could say anything intelligible about such disembodied minds, as well as all of the other difficulties involved with justifying such beliefs. Edwards focuses particularly on whether the theological answer really answers the question, mentioning a number of philosophers in this regard: “Schopenhauer referred to all such attempts to reach a final resting place in the series of causes as treating the causal principle like a ‘hired cab’ which one dismisses when one has reached one’s destination. Bertrand Russell objects that such writers work with an obscure and objectionable notion of explanation: to explain something, we are not at all required to introduce a “self-sufficient” entity, whatever that may be…Nagel insists that it is perfectly legitimate to inquire into the reasons for the existence of the alleged absolute Being…” Thus, the theological answer appears to be one of convenience that does not fully answer our query; rather, it stops the inquiry by asking no more why questions.

Edwards differentiates the theological why question—are there gods and do they provide the ultimate explanation?—from what he calls the “super-ultimate why.” A person posing this latter question regards the theological answer as not going far enough because it does not answer questions such as “Why are there gods at all?” or “Why is there anything at all?” or “Why does everything that is, exist?” The theological answer simply puts an end to why questions arbitrarily; it stops short of pushing the question to its ultimate end. One might respond that it is obsessive to continually ask why questions, but most reflective persons do ask “Why does anything or everything exist?” suggesting that the question is basic to thoughtful persons. Of course it may be that we just don’t know the answer to this ultimate mystery—all we can say is that the existence of anything is a mystery, its ultimate explanation remaining always beyond us.

According to Edwards, while some philosophers take the ultimate why question seriously many others argue that it is meaningless. The reason for this is that if a question cannot in principle be answered, as so many philosophers claim about this super ultimate why question, then that question is meaningless. Critics of this view agree that the question is radically different from all others but disagree that it is meaningless. They respond that ordinarily questions must in principle be capable of being answered to be meaningful, but not in the case of this ultimate question. Yet if a question really cannot be answered, and if all possible answers have been ruled out a priori, is that not the very definition of a meaningless question?

Another way of arriving at the conclusion that the question “why does everything exist?” is meaningless, is to consider how when we ordinarily ask “why x?” we assume the answer is something other than x. But in the case of “why anything at all?” it is not possible to find something outside of everything to explain everything. So meaningful why questions are those which are about anything in the set of all things, but if our why question is about something other than everything, then why has lost its meaning because it is logically impossible to have an answer.

Summary – How and why sometimes ask similar questions, sometimes they ask different questions. Theological whys ask meaningful questions, but this does not mean theological answers to such questions are true. Furthermore, theological answers do not answer the super-ultimate why question. The super-ultimate why question is meaningless since there cannot be something outside of everything that explains everything.

_____________________________________________________________________

Paul Edwards, “Why?” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D Klemke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 227-240.

Edwards, “Why?” 234.