John G. Messerly's Blog, page 99

December 21, 2015

Summary of Garrett Thomson: On the Meaning of Life

[image error]

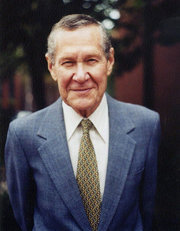

Garrett Thomson, who received his PhD from Oxford University in 1984, is the Elias Compton Professor of Philosophy at the College of Wooster in Ohio. His 2003 book, On the Meaning of Life, begins by contrasting the medieval worldview with the modern scientific one. The medieval worldview is more easily reconciled with the belief that life is meaningful because the modern one implies that “because everything is made of matter, we have no immaterial soul and so, very soon, each one of us shall die. There is probably no God … just inert matter.” The question of the meaning of life is now an urgent one “partly because the modern scientific view has largely replaced the medieval view…”

The main point of his first chapter is to clarify the meaning of the question. He carefully distinguishes, as we did in our opening chapter, between unanswerable questions, unknowable answers, and there being no universal answers to the question. In sorting out the various ways to understand the question he comes to one basic conclusion “An understanding of the meaning of life must have some practical implications for the way that we conduct our lives.” The question of meaning is not asking for a piece of information but for some guidance in living and, if it cannot give such guidance, the advice is basically useless.

Thomson proceeds to investigate nine different mistakes that people make in thinking about the meaning of life. The first assumes that meaning depends upon the existence of and our relationship with a god. He replies that the mere fact that a god has a purpose for human life does not entail that we honor that purpose. The second is that the meaning of life is some goal or purpose, whether it was planted in us by a god or evolution, or whether it refers to our spiritual development. But if we regard our lives as meaningful merely as a means to some end or goal, we invariably miss life’s intrinsic meaning. The third is that meaning is the same as pleasure or desire. This is contradicted by the fact that something would be lacking in a pleasure machine. The fourth mistake is that meaning must be invented or is subjective. In contrast he argues that activities are meaningful because of the real value associated with them. The fifth is that there can be no meaning given materialism. Thomson replies that values may be properties of material things; that material things may give rise to values; or that material things can be described as valuable. The sixth is that the value judgments are nothing more than reasons for actions. Thomson argues that there are values and meanings of which we are unaware, just like we are ignorant of some facts, and these have nothing to do with guiding actions. This implies the seventh mistake; that meaning cannot extend beyond our experiences. The eighth mistake is to assume only linguistic items can have meaning, and a ninth, that meaning is living in accord with a self-determined plan.

What all this leads to are the positive lessons of Thomson’s book. Foremost among these is that meaning is found in everyday life because that is where we reside. Individuals have intrinsic value as do the processes that constitute those lives. These processes are themselves comprised of experiences and activities that constitute a life, hence meaningful lives consist of the most valuable and meaningful activities. Life can be made more meaningful by increasing our attention and appreciation of these valuable activities, as well as becoming more aware of values in the world that we have previously not appreciated.

However, we should try to make the world and our lives better. How do we do this? Not by acting in accord with every want or desire we have but by acting in accord with our interests, with what is intrinsically good for us. This leads to a conception of value that is neither absolute nor relative. The appreciation of value implies they can be recognized, they are in some sense out there, but values are not absolute since they depend on our interests. The meanings of life are determined by our interest in valuable things like beauty and friendship. This latter value is especially important, since our meaning depends on recognizing the non-instrumental value of other persons. When we do recognize the value of others we transcend the limitations of our own lives.

We can also find meaning by connecting to values like goodness, beauty, and truth. Part of the value of our lives is found in things beyond ourselves so that the search for meaning attempts to transcend particular actions. If life has what is called spiritual significance, it is not because there is a transcendent state which denies the immanent meaning of life, but because we can appreciate the immanent values in life. Thomson’s states his conclusion regarding the meaning and significance of life as follows:

It must consist in the process of development, not according to an externally imposed divine plan or purpose, nor as a personally invented one, but rather in accordance with the fundamental nature of our interests. It should be conceived, in part, as the process of our reaching out to values beyond ourselves with our attention and actions.

Summary – The meanings of life are found in everyday life in objective values that include friendship, goodness, beauty, and truth, all of which both appeal to our nature and allow us to go beyond ourselves.

Garrett Thomson, On the Meaning of Life (Belmont CA: Wadsworth, 2003), 3.

Thomson, On the Meaning of Life, 4.

Thomson, On the Meaning of Life, 10.

Thomson, On the Meaning of Life, 157.

December 20, 2015

Joseph Ellin: Morality and the Meaning of Life

Joseph Ellin (1937 – 2011), professor emeritus at Western Michigan University and civil rights activist, received his PhD from Yale University. He concludes his 1995 book,Morality and the Meaning of Life: An Introduction to Ethical Theory , with a discussion of how meaning in life is found in objective values.

, with a discussion of how meaning in life is found in objective values.

How the Question of the Meaning of Life Arises – The question might arise because we are depressed or unhappy with our careers, love life, or health; or from the realization that we will be forgotten after we die. It might also arise because of the subjectivity of value. If values are subjective then what we do may not matter, since nothing then would be objectively right or wrong. And if nothing matters then why do anything or care about anything? A final reason the question arises is that thoughtful human beings ask: Why are we here? What does it mean? Is life going somewhere or just perpetuating itself? We want answers, hence the popularity of philosophies and religions that provide them.

Is the Meaning of Life a Kind of Knowledge? – Can the meaning of life be stated as a proposition, as knowledge or information to be passed along to others? If so is this knowledge interesting, like physics or biology, or is it useful, like plumbing or carpentry? This knowledge should not be merely interesting, since it is supposedly so important, so it should be useful. Its usefulness derives not because it makes one rich or helps someone achieve a goal; it would be useful because its intrinsically valuable, it enhance one’s life, it allows one to live it differently or see why life really is worth living. And there can be knowledge like this. If you worried that you had no friends and found out that you did, you would feel better, you would see your life differently. Now if you worried that life had no meaning what knowledge would remove that anxiety? Would knowledge that god loves you or that Buddha was your personal savior do it for you? It is not clear whether any fact or piece of information could be the meaning of life, thereby dispelling your doubts about life’s meaning.

Instead Ellin suggests that the meaning of life might be ineffable. Perhaps it is a kind of wisdom—knowing how to live well—that cannot be verbalized but when possessed makes self-evident both how one should live and the meaning of life. But even supposing there is knowledge capable of being grasped by the mind that cannot be stated, and which also reveals the meaning of life, how can one be sure they have such knowledge? How do they know—or how do we know—that they are not mistaken about possessing this knowledge? So it is hard to see how the meaning of life can be a piece of knowledge because either it can be stated propositionally—in which case it is hard to see how any fact could be the meaning of life—or it cannot be so stated—in which case one wonders if one has found it.

Moreover, even if one knew that the meaning of life was x, knowing that fact by itself does not make life meaningful. To make life meaningful you must act on your knowledge by loving god, making friends, seeking knowledge or whatever you are supposed to do. But these are not facts; they are prescriptions or injunctions concerning action.

Is the Meaning of Life Happiness? – Perhaps what is missing in a meaningless life is happiness. If you think life has no meaning maybe you are unhappy. What is the relationship between meaning and happiness? Meaning may be a necessary condition for happiness—you cannot be happy without meaning—but people differ in what makes them happy and what they think is meaningful. Or meaning may be a sufficient condition for happiness—if you have meaning, you have happiness. For instance if you do noble work that gives your life meaning you would be happy, even if you lack all other elements of happiness. Maybe then happiness and meaning occur together, if you have one you have the other. Of course this does not mean that they are the same thing, and it does not tell us what meaning is.

Nevertheless, we do have reason to think that having meaning and being happy are not the same, for we can be unhappy for many reason, lack of meaning is just one of them. So even if meaning is a necessary condition for happiness, it is not sufficient. Having meaning does not guarantee happiness, although it does prevent a certain kind of unhappiness, the kind that follows from lack of meaning.

The Death Argument – So what is lost when we lose meaning? What does life not have when meaning is lost? A good way to understand this is to look again at Tolstoy, for whom death undermined meaning. But does death take the meaning out of life? Tolstoy’s argument is:

Life is good;

Death ends this goodness; thus

Death is bad; thus

Life is meaningless.

As Ellin points out this argument does show that death is bad, but it does not show that death removes meaning. In fact the badness of death reveals the goodness of life. Most persons fear death precisely because they want to live. Still, some argue that death is not bad because it is nothing and cannot harm you. Ellin agrees that death cannot harm you but it is still bad because your annihilation is harmful to you, it is the greatest harm that can befall you. Other reasons for thinking death is not evil include the idea that eternity would be boring or that the prospect of death forces us to do things we would otherwise put off.

Despite these arguments Ellin concludes that death is bad. It is something that we want to avoid but which is inevitable. The best we can do is to be as unconcerned about our not being alive in the future, as we are now about our not being alive in the past. Still, the evil of death does not show that life is meaningless.

Repetitive Pointlessness, Ultimate Insignificance, and Absurdity – What other considerations might lead then to the conclusion that life is meaningless? Ellen notes three. First there are Camus’ ideas about the repetitiveness and pointlessness of Sisyphus’ labor. Ellin responds that most lives are not like this, containing at least some variation as well as goals that give those lives a point. He also wants to know what would count as a meaningful life. Either you can state what makes life meaningful or you cannot. If you can state this but claim that no one can achieve it—you must win a noble prize and be immortal—why should we accept your high standards for a meaningful life? If you cannot state what counts as a meaningful life but say that life cannot have a point by definition—you beg the question. To show that life is meaningless you have to show that what most people think gives life meaning does not. To do this Camus would have to show that every life is like Sisyphus’. Needless to say this would be nearly impossible.

A second consideration that might lead to the conclusion that life is meaningless is our ultimate insignificance. Russell thought that the vast expanses of space and time discovered by science reveals the insignificance of our lives. For Russell cherishing perfection, mathematics, art, love, and truth is the best attitude to adopt in an uncaring universe. In this way we preserve our ideals without wishful thinking. Ellin responds that the presence or absence of the universe has nothing to do with meaning. If the rest of the universe was absent, if only earth existed, why would that add to meaning? And if it does not, then why does the presence of a vast universe destroy meaning?

A final consideration that might lead to thinking that life is meaningless results from the notion of absurdity. The idea that life is absurd, irrational, and pointless is common to many modern thinkers, especially existentialists like Jean Paul Sartre, who responded that individuals must create their own values and meaning. Still, others maintain that life is not a tragedy but a farce, and the appropriate response accepts that we are ridiculous. Although there are many responses to the supposed meaninglessness of life—Tolstoy’s leap of faith, Camus’ defiance, Russell’s upholding ideals, Sartre’s terror—Ellin doubts that we must accept life’s meaningless in the first place.

“Big Picture” Meaning and Faith – Is your life meaningful if it is part of a larger scheme? How does a big picture view give something meaning? Ellin gives the examples of a shortstop in baseball or a soldier in an army. In both cases their actions appear unimportant, pointless, and meaningless unless you understand the big picture of which they are a part. We often understand the meaning of activity in precisely this way. Ellin argues that we want a big picture to explain: 1) the purpose of all life; 2) our individual lives by reference to that purpose; 3) how suffering and death are necessary for that purpose; and 4) how life is good.

The big picture is usually explained by a story, but not any story will do—being food for a super race making an intergalactic journey will not do. Such a story satisfies the first three criteria, but not the fourth. Religious stories typically fulfill all four criteria but they may not be true. Note that we don’t need to believe all the details of the story, we only need to believe that there is a big picture. After all life may be like a movie of which we have only seen fragments. We don’t know the meaning of the movie, but we can believe there is one anyway; we can have faith that if we saw the entire movie, we would understand its meaning. True we don’t know this with certainty but deep truths are often beyond are grasp. Believing in a big picture is thus a reasonable option; and it is reasonable to believe that life makes sense after all. But why believe in something for which there is little or no evidence? How do we believe in something when we don’t know what that something is? And how does such a belief differ from no belief, since it tells you nothing about what to do or value?

Is the Question of Meaning Meaningful? – Ellin now adumbrates the typical objections of the logical positivist. Words, sentences, and actions refer to things but life refers only to itself, hence it cannot be the kind of thing that has meaning. Thus the question does not make sense. To put the point another way, a question only makes sense if we have some idea of the range of answers to the question. With the meaning of life question, we don’t know what would count as an answer. The upshot of all this is that we feel even less secure of proposed solutions.

If Life Has No Meaning, What Then? – In summary Ellin claims that the meaning of life is not a piece of knowledge, not the same as happiness, but not ruled out by death. The arguments from repetitive pointlessness, ultimate insignificance, and absurdity are not entirely convincing, but neither are the arguments that there is a big picture from which to derive meaning. This all suggest that life may have no meaning, or that if there is meaning it is beyond us, or that the question makes no sense. Some, like Tolstoy, respond to this situation with an optimistic belief that the big picture is good; others, like Camus and Russell, respond with heroic pessimism toward an ultimately meaningless cosmos.

Both the optimists and pessimists agree that life must have meaning to be worthwhile. Could it be that this is mistaken? Ellin suggests that while life as a whole may have no meaning, individuals lives still can. You can have friends and knowledge and love and all the rest; you can say of a life that the world is better because that person lived. But the universe cannot give you meaning, you must give meaning to your life: “…meaning is not a kind of knowledge at all … but at bottom a feeling, a sense of well-being from having made a difference.”

So it appears Ellin agrees with the subjectivists, but not quite. He now asks: Will any activity suffice in giving one’s life meaning? No he argues. Finding things you are good at and developing those talents is not sufficient, inasmuch as being a wonderful child torturer or crime boss would satisfy those requirements. Lives better off not lived; those that did not make useful contributions to the world are not meaningful. Immoral lives are not meaningful: “… a truly valuable life is one of which more people than not have reason to be glad that the life was lived.”Although there is no ultimate justification for our lives; we can still give them meaning. But to have the most meaning possible, morality must be part of our lives—it is the means to the objective values of love, friendship, loyalty and trust that make life worth living.

Summary – The meaning of life is not a kind of knowledge, not the same as happiness, not completely undermined by death, not made obvious by religious stories, and, if actual, possibly unknowable. Still, nothing compels us to accept that life is meaningless for we can derive meaning from life by discovering objective moral goods and leading live in accord with them.

____________________________________________________________________

Ellin, Morality and the Meaning of Life, 327.

December 19, 2015

Naturalism and Objective Meaning

Most of us have known some golden days in the June of life when philosophy was in fact what Plato calls it, “that dear delight;” when the love of a modestly elusive truth seemed more glorious – incomparably – than the lust for the ways of the flesh and the dross of the world. And there is always some wistful remnant in us of that early wooing of wisdom. “Life has meaning,” we feel with Browning. “To find its meaning is my meat and drink.”… So much of our lives is meaningless, a self-canceling vacillation and futility. We strive with the chaos about and within, but we should believe all the while that there is something vital and significant in us, could we but decipher our own souls. We want to understand. “Life means for us constantly to transform into light and flame all that we are or meet with!” We are like Mitya in The Brothers Karamazov – “one of those who don’t want millions, but an answer to their questions.” ~ Will Durant

If one finds both the supernatural and subjective answers unsatisfying, then perhaps meaning is objective and found in the natural world. Objectivists believe that (at least some) meaning is independent of their desires, attitudes, interests, wants, and preferences; that there are invariant standards of meaning independent of human minds. Such meaning is not derived from a supernatural realm, but from objective elements in the natural world. However, this does not mean that value or meaning is exclusively objective, as the following thinkers will note. Effort on the part of the subject is necessary to derive or discover the objective meaning in the world. In forthcoming posts we will look at a number of thinkers who find meaning in the objectively good things of the natural world.

What is Love?

I have discussed love in a number of previous posts here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. But it occurs to me that we need to carefully define love. We need to answer the question, what is love?

The Different Kinds of Love

The Greeks distinguished at least 6 different kinds of love:

1) Eros was the notion of sexual passion and desire but, unlike today, it was considered irrational and dangerous. It could drive you mad, cause you to lose control and make you a slave to your desires. The Greeks advised caution before one gives into these desires.

2) Philia denoted friendship which was thought more virtuous than sexual or erotic love. It refers to the affection between family members, colleagues, and other comrades. However these persons are much closer to you than Facebook friends or Twitter followers.

3) Ludus defines a more playful love. This ranges from the playful affection of children all the way to the flirtation or the affection between casual lovers. Playing games, engaging in casual conversation, or flirting with friends are all forms of this playful love.

4) Pragma refers to the mature love of lifelong partners. After a lifetime of compromise, tolerance, and shared experiences a calm stability and security ensues. Commitment between partners is the key; they mutually support and respect each other.

5) Agape is a radical, selfless, non-exclusive love; it is altruism directed toward everyone (and perhaps to the environment too.) It is love extended without concern for reciprocity. Today we would call this charity; or what the Buddhists call loving kindness.

6) Philautia is self-love. The Greeks recognized two forms. In its negative form philautia is the selfishness that wants pleasure, fame, and wealth beyond what one needs. Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection, exemplifies this kind of self-love. In its positive form philautia refers to a proper pride or self-love. We can only love others if we love ourselves; and the warm feelings we extend to others emanate from good feelings we have for ourselves. If you are self-loathing, you will have little love to give.1

These distinctions undermine the myth of romantic love so predominant in modern culture. People obsess about finding soul mates, that one special person who will fulfill all their needs—a perpetually erotic, friendly, playful, selfless, stable partner. In reality no person fulfills all these needs. And the twentieth-century commodification of love renders the situation even worse. We buy love with engagement rings; market ourselves with clothes, body modifications, Facebook profiles, and on internet dating sites; and we look for the best object we can find in the market given an assessment of our trade value.

This is not to suggest that everything is wrong with the modern world or that the internet isn’t a good place to find a mate—it may be the best place. (Although I’m much too old to worry about it!) Rather I suggest that to be satisfied in love, as in life, one must cultivate multiple interests, strategies, and relationships. We may get the most stability from our spouse, but find playful times with our grandchildren or our golfing partners; we may find friendship with our philosophical comrades; and we might find an outlet for altruism in our charitable contributions or in productive work.

As for our most intimate relationships, we would do best to lower our expectations—again no one satisfies all our needs. As I said in my previous post, this is not the idealized love of Hollywood movies, but it is real love. No, you won’t have heart palpitations every time you see your beloved after 35 years, but you will feel the presence that accompanies a lifetime of shared love, a lifetime of struggling and fighting and working together. You will feel the continuity of knowing someone who knew you when you were young, middle age, and old, and they will feel the same. The accompanying serenity is peaceful and priceless. I hope everyone can experience this.

1. Rousseau made a similar distinction between amour-propre and amour de soi. Amour de soi is a natural form of self-love; we naturally look after our own preservation and interests and there is nothing wrong with this. By contrast, amour-propre is a kind of self-love that may arise when we compare ourselves to others. In its corrupted form, it is a source of vice and misery, resulting in human beings basing their own self-worth on their feeling of superiority over others.

December 18, 2015

What Should We Be Afraid Of?

My last post, “Guns are security blankets not insurance policies,” discussed the irrationality that motivates people to possess firearms. This post tries to partly explain why fear in general is such a powerful motivator.

There is a lot to say about why fear motivates us, but the explanation is no doubt neurophysiological, relating to the amygdala, the sympathetic nervous system, and other elements of the reptilian and paleomammalian parts of the human brain. This physiology combined with a cultural environment which exaggerates risks—the firearms industry, the military industrial complex, certain news organizations, etc.—creates a situation in which people constantly misconstrue risks.

Consider that about 32,000 Americans die every year on America’s roads in motor vehicle accidents—many less than 30-40 years ago thanks to government regulations of the auto industry—and well over a million people around the world die every year in auto accidents. Moreover, 5,000 pedestrians a year die in traffic accidents each year in America alone. Yet people hop in cars and cross the street everyday without fear—yet we don’t go to war against cars!

Now think about the time Americans spend worrying about being killed by terrorists and the amount of money spent on wars and security to defeat it. Is being killed by a terrorist (whatever that means) something to really be afraid of? No, for as Timothy Egan put it in his recent New York Times op-ed, “What to be Afraid Of,”

You are much more likely to be struck dead by lightning, choke on a chicken bone or drown in the bathtub than be killed by a terrorist. Any number of well-known diseases—cancer, diabetes, the flu—take the lives of far, far more people. Yet, by one estimate, the United States spends $500 million per victim of terrorism, and a piddling $10,000 per cancer death.

Consider that cancer and heart disease kill more than a million Americans each year and that only a handful of Americans die each year as a result of terrorism. In 2011 the US State Department reported 17 US non-combatants killed as a result of terrorism. (To put this in perspective about 50 people are killed annually in the US by lightning.) In fact your chances as a US citizen of being killed by a terrorist are vanishingly small compared to other risks. Yet the US spends 50,000 times as much per victim on death from terrorists as deaths from cancer.

And this is not even to mention that over 16,000 Americans are murdered each year in their own country, more than 11,000 of those by firearms. If you do want to be afraid, look around you at your fellow Americans, not mostly imaginary, foreign bogeymen. There is so much more to be said about all this, but we’ll let Egan have the last words:

So what should you be afraid of? Are you sitting down? Get up—you shouldn’t be. Sitting for more than three hours a day can shave life expectancy by two years, through increased risk of heart disease or Type 2 diabetes …

“Guns are security blankets, not insurance policies”

At his wonderful blog, The Weekly Sift, the mathematician Doug Mudar posted an insightful piece recently about the psychology of gun owners titled: “Guns are security blankets, not insurance policies.” He begins with a quote from the sci-fi author William Gibson: “People who feel safer with a gun than with guaranteed medical insurance don’t yet have a fully adult concept of scary.” This, Mudar notes, explains a lot about the gun-control debate in America today.

Mudar points out that proponents of gun control tend to cite statistics about how many more homicides and suicides we have in America compared to other countries with fewer guns, or how much more likely you are to kill yourself or a household member than an intruder, and so on. While pro-gun advocates tend to tell what-if fantasy stories to defend their position. “What if home invaders came to kill you, kidnap your baby, or rape your teen-age daughter? What if you were a hostage in a bank robbery? What if you were at a restaurant or grocery store when terrorists broke in and started killing people? Wouldn’t you wish you had a gun then?”

Mudar says that these camps have “two very different ways to think about risk and security. One is the mature, rational way. What are the most likely risks and how can we mitigate them. So while people in America tend to worry about things like terrorists attacks and plane crashes, which pose virtually no risk to them, they forget about mundane risks like car accidents, heart disease and cancer which pose far, far greater risk. If you really want to be safe do things like wear your seat belt, eat well, exercise and don’t smoke.

The other way to think about risk is the childish, irrational way. In this mode you worry about monsters in your closet or ghosts in your room. Now frightened children aren’t always assured when you tell them that the chances of being eaten by a monster or haunted by a ghose are very, very low. Sometimes it is better to give the child “a security blanket or a teddy bear” to serve as a talisman to create an aura of security. And that’s what guns do for most gun owners. As Mudar concludes:

The point isn’t that home invasion is a major risk in your life , that you are well-trained enough to win a middle-of-the-night shoot-out if home invaders show up, or even that you have a practical way to get the gun out of its safe-storage location in time to use it at all; it’s that when the home-invasion fantasy plagues you, you can tell yourself, “It’s OK. I have a gun.”

(Of course, some people have real security problems whose solution may involve guns. For example, four Presidents of the United States, about 1 in 10, have been assassinated, others have been the target of assassinations, and all receive numerous threats. US Presidents have special security risks. But most of us aren’t presidents, drug dealers or the kinds of people for whom being shot is much more than an imaginary monster.)

In my next post I’ll briefly discuss the origins of irrational fears.

December 17, 2015

Is the Meaning of Life Subjective?

(This post summarizes and comments on posts of the previous few weeks. For more about the specific philosophers mentioned here see those posts.)

Baier’s arguments against the religious conception of objective meaning are convincing, as is his claim that life can have subjective meaning nonetheless. Edwards expands on this theme, arguing that life can have terrestrial meaning even if we cannot show that existence itself is ultimately worthwhile. Edwards also claims that subjective meaning is enough for most people, but this argument is problematic. I do not think that ordinary people are content with subjective meaning. To the contrary nearly the entire edifice of human culture—art, science, religion, philosophy—emanates from the desire to have our lives mean something in the cosmic sense. Those content with meaning in the terrestrial sense are the exception; those searching for the meaning of their lives in the cosmic context don’t have special standards as Edwards claims.

Flew makes the same basic claim, meaning is found in life even if there is no meaning of life, but he asks us to forego our dreams of immortality and make a better world. Barnes asks us to grow up and create meaning in a world without gods, comforted by the fact that there is some small immortality in the repercussions that emanate from our lives. For Barnes we create the rules of the game. In the end neither Flew nor Barnes satisfies our desire for meaning anymore than Baier or Edwards. They all counsel us to accept that meaning in life is all we can get. But we want more than subjective meaning even if that’s all we can have.

In Martin’s analysis we find despair—a fast car and a good woman cannot satisfy for long. The only comfort in his analysis is that death is a welcome relief from our insatiable appetites. Kekes moves the argument further along, detaching meaning from anything objective, including morality. He thus brings us back to active engagement in our lives without moral limitations as the source of meaning. For Schmidt finding meaning in whatever we are engage—such as coaching little league football—is about the best we can do, while Solomon suggests we choose a vision of life without telling us how to do this or whether some vision is better than others. Lund recommends that we give our lives meaning by searching for what we will probably never find, but that the searching is as close to meaning as we will probably ever come. These are all brave words from brave men, and their poignancy is felt deeply. Baggini’s account is the most uplifting, we can give our lives meaning by loving, but even love has its limits, is fragile, and exists without transcendental support.

Russell argued that persons free of metaphysical narratives can find some meaning in the beauty they create and the truth they find; Taylor argued that our labors are precisely what give our lives meaning, since they are motivated by our inner nature; Hare claimed that we bestow mattering on the world; Singer that we create meaning by creating and loving; and Klemke claimed that we can live without appeal by finding subjective meaning in art, work and love. All these thinkers maintain that creating meaning is all we have left once objective meaning is lost. Still, something important is missing from all of these accounts. Something we deeply long for—that our labors matter not just to us but to the cosmos, and that we are part of something bigger than the attachment to our will. What such lives lack is objective meaning. Is loving computers, golf, sunsets, or children really enough?

Consider for example Hare’s response to his young guest. The reason that Meursault was relevant for the boy was because he identified with Meursault. True, the boy was not facing execution, but he recognized that we all die. The young boy was moved because he saw his own life revealed in a new way by the novel. Yes, the young man later admitted that things did matter to him, but suppose when asked if anything mattered to him the boy had said no? How then would Hare reply? Would he have screamed: “No, some things do matter to you!” If the boy demurred, then they would have been at an impasse, and that is why Hare counsels that some things are objectively valuable. But what if the young man denied this?

In the same way the beauty, perfection, work, art, and love that Russell and Taylor and Klemke appeal to seems tainted, not because they are not worthwhile and not because we might not care about them, but because they are not worthwhile enough to satisfy us. The foregoing discussion reveals the basic problem with creating your own meaning—such a requirement asks too much. How is a lone individual to make their lives meaningful by themselves against the backdrop of the infinity of space and time? Is it really something we can create, all by ourselves? Yes, we can collect baseball cards and find that meaningful, but surely that is not enough and we are right to be dissatisfied if there is nothing more to life than that. And even if we can shake our fist at the world, create some momentary perfection, have relationships or coach little league, how can we resist asking: is that all there is?

If transcendental support for meaning is absent, and subjective meaning is not enough, then we must turn to objective meanings and values inherent in human experience, ones that exist in the natural world. It is to such considerations that we now turn. (I will resume this discussion of the meaning of life the day after tomorrow.)

December 16, 2015

Summary of E. D. Klemke’s, “Living without Appeal”

E.D. Klemke (1926-2000) taught for more than twenty years at Iowa State University. He was a prolific editor and one of his best known collections is The Meaning of Life, first published in 1981. (Almost all of the articles of every edition of that text have been summarized in this book.) The following summary is of his 1981 essay: “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life.”

Klemke begins by stating that the topics of interest to professional philosophers are abstruse and esoteric. This is in large part justified as we need to be careful and precise in our thinking if we are to make progress in solving problems; but there are times when a philosopher ought to “speak as a man among other men.” In short a philosopher must bring his analytical tools to a problem such as the meaning of life. Klemke argues that the essence of the problem for him was captured by Camus in the phrase: “Knowing whether or not one can live without appeal is all that interests me.”[ii]

Many writers in the late 20th century had a negative view of civilization characterized by the notion that society was in decay. While the problem has been expressed variously, the basic theme was that some ultimate, transcendent principle or reality was lacking. This transcendent ultimate (TU), whatever it may be, is what gives meaning to life. Those who reject this TU are left to accept meaninglessness or exalt natural reality; but either way this hope is futile because without this TU there is no meaning.

Klemke calls this view transcendentalism, and it is composed of three theses: 1) a TU exists and one can have a relationship with it; 2) without a TU (or faith in one) there is no meaning to life; and 3) without meaning human life is worthless. Klemke comments upon each in turn.

1. Regarding the first thesis, Klemke assumes that believers are making a cognitive claim when they say that a TU exists, that it exists in reality. But neither religious texts, unusual persons in history or the fact that large numbers of persons believe this provide evidence for a TU—and the traditional arguments are not thought convincing by most experts. Moreover, religious experience is not convincing since the source of the experience is always in doubt. In fact there is no evidence for the existence of a TU and those who think it a matter of faith agree; there is thus no reason to accept the claim that a TU exists. The believer could counter that one should employ faith to which Klemke responds: a) we normally think of faith as implying reasons and evidence; and b) even if faith is something different in this context Klemke claims he does not need it. To this the transcendentalist responds that such faith is needed for there to be a meaning of life which leads to the second thesis:

2. The transcendentalist claims that without faith in a TU there is no meaning, purpose, or integration.

a. Klemke firsts considers whether meaning may only exist if a TU exists. Here one might mean subjective or objective meaning. If we are referring to objective meaning Klemke replies that: i) there is nothing inconsistent about holding that objective meaning exists without a TU; and ii) there is no evidence that objective meaning exists. We find many things when we look at the universe, stars in motion for example, but meaning is not one of them. We do not discover values we create, invent, or impose them on the world. Thus there is no more reason to believe in the existence of objective meaning than there is to believe in the reality of a TU.

i. The transcendentalist might reply by agreeing that there is no objective meaning in the universe but argue that subjective meaning is not possible without a TU. Klemke replies: 1) this is false, there is subjective meaning; and 2) what the transcendentalists are talking about is not subjective meaning but rather objective meaning since it relies on a TU.

ii. The transcendentalist might reply instead that one cannot find meaning unless one has faith in a TU. Klemke replies: 1) this is false; and 2) even if it were true he would reject such faith because: “If I am to find any meaning in life, I must attempt to find it without the aid of crutches, illusory hopes, and incredulous beliefs and aspirations.” Klemke admits he may not find meaning, but he must try to find it on his own in something comprehensible to humans, not in some incomprehensible mystery. He simply cannot rationally accept meaning connected with things for which there is no evidence and, if this makes him less happy, then so be it. In this context he quotes George Bernard Shaw: “The fact that a believer is happier than a skeptic is no more to the point than the fact that a drunken man is happier than a sober one. The happiness of credulity is a cheap and dangerous quality.”

b. Klemke next considers the claim that without the TU life is purposeless. He replies that objective purpose is not found in the universe anymore than objective meaning is and hence all of his previous criticisms regarding objective meaning apply to the notion of objective purpose.

c. Klemke now turns to the idea that there is no integration with a TU. He replies:

i. This is false; many persons are psychologically integrated or healthy without supernaturalism.

ii. Perhaps the believer means metaphysical rather than psychological integration—the idea is that humans are at home in the universe. He answers that he does not understand what this is or if anyone has achieved it, assuming it is real. Some may have claimed to be one with the universe, or something like that, but that is a subjective experience only and not evidence for any objective claim about reality. But even if there are such experiences only a few seem to have had them, hence the need for faith; so faith does not imply integration and integration does not need faith. Finally, even if faith does achieve integration for some, it does not work for Klemke since the TU is incomprehensible. So how then does Klemke live without appeal?

3. He now turns to the third thesis that without meaning (which one cannot have without the existence of or belief in a TU) life is worthless. It is true that life has no objective meaning—which can only be derived from the nature of the universe or some external agency—but that does not mean life is subjectively worthless. Klemke argues that even if there were an objective meaning “It would not be mine.” In fact he is glad there is not such a meaning since this allows him the freedom to create his own meaning. Some may find life worthless if they must create their own meaning, especially if they lack a rich interior life in which to find the meaning absent in the world. Klemke says that: “I have found subjective meaning through such things as knowledge, art, love, and work.” There is no objective meaning but this opens us the possibility of endowing meaning onto things through my consciousness of them—rocks become mountains to climb, strings make music, symbols make logic, wood makes treasures. “Thus there is a sense in which it is true … that everything begins with my consciousness, and nothing has any worth except through my consciousness.”

Klemke concludes by revisiting the story told by Tolstoy of the man hanging on to a plant in a pit, with dragon below and mice eating the roots of the plant, yet unable to enjoy the beauty and fragrance of a rose. Yes, we all hang by a thread over the abyss of death, but still we possess the ability to give meaning to our lives. Klemke says that if he cannot do this—find subjective meaning against the backdrop of objective meaninglessness—then he ought to curse life. But if he can give life subjective meaning to life despite the inevitability of death, if he can respond to roses, philosophical arguments, music, and human touch, “if I can so respond and can thereby transform an external and fatal event into a moment of conscious insight and significance, then I shall go down without hope or appeal yet passionately triumphant and with joy.”

Summary – The meaning of life is found in the unique way consciousness projects meaning onto an otherwise tragic reality.

_______________________________________________________________

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 194.

December 15, 2015

Irving Singer: The Meaning of Life

Irving Singer (1925 – 2015) was Professor of Philosophy at MIT where he began teaching in 1958. He was a voluminous writer, and the author of Meaning in Life in three volumes, as well as the three volume trilogy, The Nature of Love.

Singer says there are basically three positions regarding the meaning of life: a) traditional religious answers; b) nihilistic answers; and c) create our own meaning answers. Singer grants that religious answers provide many persons with meaning but he rejects them: “this pattern of belief is based on non-verifiable assumptions that exceed the limits of natural events and ordinary experience. Take away the transcendental props, which nowadays have become wobbly after centuries of criticism, and the grand edifice cannot stand. The challenge in our age is to understand how meaning can be acquired without dubious fantasying beyond the limits of our knowledge.”

Singer also rejects nihilism, especially the idea that the universe is indifferent to whatever we value. Singer counters that what we want is valuable to us whether or not the universe cares. Our values originate in our human condition; they spring from, but do not contradict, a world that we should not expect to care about us anymore than we expect this of other inanimate things. One can consistently hold that they both act with purpose and that the universe is purposeless. Our values do not exist from the eternal perspective, but they are not arbitrary, irrational, or absurd; our values emanate from our evolved nature.

While Singer’s thoughts on the topic are vast and complex, the secret to understanding it is found in the title of his first major book on the subject, Meaning in Life: The Creation of Value (Volume 1). Meaning is something we create. Yet he is sensitive to the rejoinder that regardless of what matters to us subjectively, nothing matters objectively. Here he notes two responses: 1) if something matters to an individual then it matters, period; and 2) if nothing matters then it doesn’t matter that nothing matters. However, neither response reassures. That things matter only to us is not enough, and that things do not matter at all provides no comfort.

In response to this conundrum we might welcome the notion that nothing matters. If we embrace this thought we may no longer be tormented by a social faux pas or even by the fact that all our efforts will finally come to nothing. We may no longer need to contrast the meager with the important; we could leave self-righteousness behind, accepting ourselves and others. But what then should we do, what then should we value? The idea that nothing matters is ultimately unhelpful.

Instead Singer argues that accepting that nothing matters is to lose touch with one’s instincts, as we naturally find things matter to us. By simply being alive we reveal that things do matter to us; in large part being alive is about choosing what does and does not matter to us. That something matters is a prerequisite for life, and specifically what matters is what brings happiness and meaning to individuals.

Yet none of this means there is a reality behind the appearances that gives meaning to life as the optimists claim. “Our mere existence in time, as creatures whose immersion in past and future prevents us from adequately realizing the present, convinces me that the optimists are deluding themselves.” Like Emily Gibbs in Wilder’s Our Town, we seem incapable of realizing life while we life it. And while some like Plato and Whitehead have posited eternal objects as a solution to the passage of time, Singer rejects these as mere abstractions and static—unlike life.

All of this leads Singer back to the question: Is life worth living? He answers that we must participate in significant creative acts to make our lives meaningful. To clarify what he means Singer quotes George Bernard Shaw:

This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; the being a force of Nature instead of a feverish selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy. And also the only real tragedy in life is the being used by personally minded men for purposes which you recognize to be base. All the rest is at worst mere misfortune or mortality: this alone is misery, slavery, hell on earth; and the revolt against it is the only force that offers a man’s work to the poor artist, whom our personally minded rich people would so willingly employ as pander, buffoon, beauty monger, sentimentalizer and the like.

Singer grants that Shaw does not tell us how to be forces of nature or what it means to be true to our nature. But for Singer this includes at a minimum an acceptance of our nature and self-love. Self-love is not the same as vanity; rather it enhances our ability to love others. And although we may not be able to love all of life, or love others as much as we love ourselves, we can see others as possible objects of our love. As everything loves itself, inasmuch as they do what they can to preserve themselves, there is love in everything. We can try to love the love that is in everything. As Singer puts it:

Those who love the love in everything, who care about this bestowal and devote themselves to it, experience an authentic love of life. It is a love that yields its own kind of happiness and affords many opportunities for joyfulness. Can anything in nature or reality be better than that?

Summary – We give meaning to life by loving the good in everything.

__________________________________________________________________

Singer, Meaning in Life: The Creation of Value, 148.

December 14, 2015

Summary of R. M. Hare’s: “Nothing Matters?”

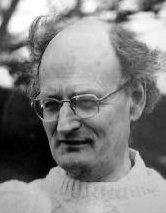

R.M. Hare (1919 – 2002) was an English moral philosopher who held the post of White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford from 1966 until 1983, after which he taught for a number of years at the University of Florida. He was one of the most important ethicists of the second half of the twentieth century.

Hare begins his essay, “Nothing Matters,” by telling the story of a happy 18 year old Swiss boy who stayed with Hare in his house at Oxford. After reading Albert Camus’ The Stranger, the boy’s personality changed, becoming withdrawn, sullen, and depressed. (The Stranger explores existential themes like death and meaning; its title character Meursault is emotionally alienated, detached, and innately passive.) The boy told Hare that after reading Camus he had become convinced that nothing matters. Hare found it extraordinary that the boy was so affected.

As a philosopher concerned with the meaning of terms, Hare asked the young boy what “matters” means, what does it mean to matter or be important? The boy said that to say something matters “is to express concern about that something.” But Hare wondered whose concern is important here? When we say the something matters, the question arises, “matters to whom?” Usually it’s the speaker’s concern that is expressed, but it could be someone else’s concern. We often say things like “it matters to you,” or “it doesn’t matter to him.” In these cases we refer not to our own concern, but to someone else’s.

In Camus’ novel the phrase “nothing matters” could express the view of the author, the main character, or the reader (the young boy.) Now it’s not Camus’ unconcern that is being expressed, since he was concerned enough to write the novel—writing the novel obviously mattered to Camus. It is clear in the novel that the main character does think that nothing matters—he doesn’t care about hardly anything. Still, Hare thinks that even Meursault is concerned about some things.

Hare doesn’t think it possible to be concerned about nothing at all, since we always choose to do one thing rather than another thereby revealing, however slightly, what matters to us. At the end of Camus’ novel Meursault is so upset by the priest’s offer of religion that he attacks him in a rage. This display of passion shows that something did matter to Meursault, otherwise he would have done nothing. Yet even supposing that nothing does matter to a fictional character: why should that matter to the Swiss boy? In fact the boy admitted that he cares about many things, which is to say that things do matter to him. Hare thinks the boy’s problem was not to find things that matter, but to prioritize them. He needed to find out what he valued.

Hare claims that our values come from our own wants and the imitation of others. Maturing in large part is bringing these two desires together—the desire to have our own values and to be like others with the former taking priority. “In the end…to say that something matters for us, we must ourselves be concerned about it; other people’s concern is not enough, however much in general we may want to be like them.” Nonetheless we often develop our own values by imitating others. For instance we may pretend to like philosophy because we think our philosophy professor is cool, and then gradually we develop a taste for it. This process often works in the reverse; my parents want me to do x, so I do y. Eventually, through this process of conforming and non-conforming, we slowly develop our own values.

Hare concludes that things did matter to the young boy and he was just imitating Meursault by saying that nothing matters, just as he was imitating him by smoking. What the boy did not understand was that matter is a word that expresses concern; it is not an activity. Mattering is not something things do, like chattering. So the phrase “my wife chatters,” is not like the phrase “my wife matters.” The former refers to an activity; the latter expresses my concern for her. The problem comes when we confuse our concern with an activity. Then we start to look in the world for mattering and when we do not find things actively doing this mattering, we get depressed. We do not observe things mattering, things matter to us if we care about them. Mattering doesn’t describe something things do, but something that happens to us when we care about things. To say nothing mattes is hypocritical; we all care about something. (Even if what we care about is that nothings seems to matter.)

As for his Swiss friend, Hare says he was no hypocrite; he was just confused about what the word matter meant. Hare also suggests that we are the kinds of beings who generally care about things, and those who sincerely care about almost nothing are just unusual. In the end we cannot get rid of values—we are creatures that value things. Of course when confronted with various values, so many different things about which to be concerned, it is easy to through up our hands and say that nothing matters. When confronted with this perplexity about what to be concerned about, about what to value, Hare says we might react in one of two ways. First, we might reevaluate our values and concerns to see if they are really ours; or second, we might stop thinking about what is truly of concern altogether. Hare counsels that we follow the former course, as the latter alternative leads to stagnation: “We content ourselves with the appreciation of those things, like eating, which most people can appreciate without effort, and never learn to prize those things whose true value is apparent only to those who have fought hard to achieve it…”

Summary – We all generally care about some things, some things do matter to us. We don’t find this mattering in the world; it is something we bestow upon things and persons. Hare suggests we find value (or meaning) in things which are really worthwhile.

___________________________________________________________________

Hare, “Nothing Matters,” 47.