John G. Messerly's Blog, page 97

January 9, 2016

Summary of Stephen Rosenbaum’s, “How to Be Dead and Not Care: A Defense of Epicurus”

Stephen Rosenbaum is Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas. He received his PhD in philosophy from the University of Illinois. In his 1986 piece, “How to Be Dead and Not Care: A Defense of Epicurus,” he rejects the view that death is bad for the person that dies, undertaking a systematic defense of the Epicurean position. As we have seen, while we ordinarily think that death is bad for the person that dies, Epicurus argued that this is mistaken. And, since fear of something that is not bad is groundless, it is irrational to fear death.

Rosenbaum begins by differentiating between: 1) dying—the process that leads to death; 2) death—the time at which a person becomes dead; and 3) being dead—the state after death. The Epicurean argument does not deny that dying or death can be bad, but argues that being dead cannot be bad for the one who is dead. Just as a totally deaf person cannot experience a Mozart symphony, a dead person cannot have positive or negative experiences. The purpose of Epicurus’ argument, according to Rosenbaum, was to help us achieve inner peace and to free us from unnecessary fear and worry. It also was a meant to revise common sense in light of philosophical reflection. Rosenbaum reconstructs that argument as follows:

A state of affairs is bad for a person P only if they can experience it; thus

P’s being dead is bad for P only if it is a state P can experience;

P can experience a state of affairs only if it begins before P’s death;

P’s being dead is not a state of affairs that begins before P’s death; thus

P’s being dead is not a state of affairs that P can experience; thus P’s being dead is not bad for P.

Since B and E are logical deductions, only A, C, and D are premises. Since D is true by definition, only premises A and C are possibly controversial, but Rosenbaum argues that both stand up to critical scrutiny. The only way to attack the argument then is if it misses the entire point. Perhaps death is bad because we anticipate not having experiences, opportunities, and satisfactions. Rosenbaum responds that such anticipations occur only while we are alive; they cannot be experienced after we are dead. That is why anticipating death is not like anticipating going to the dentist. In the latter both the anticipation and the actual experience of the dental chair are bad, while in the former there is only the anticipation. In fact Epicurus thought the anticipation pointless, since there would be no badness after death. But if Epicurus’ argument is sound, why do many fear death?

Lucretius offered an explanation. Since we have a hard time thinking of ourselves as separate from our bodies, we think that bad things happening to our bodies are happening to us. We think of the decaying body as somehow us, but it is not. Another possible explanation is that we believe death takes us to some other realm that will be highly unpleasant. But Epicurus can apply a salve to our concerns—being dead is nothing to the dead person.

Summary – The Epicurean argument that death is not bad and nothing to fear is sound. Being dead is not bad for the dead person.

____________________________________________________________________

Stephen Rosenbaum, “How to Be Dead and Not Care: A Defense of Epicurus,” American Philosophical Quarterly 23 no. 2 (April 1986).

January 8, 2016

Summary of Vincent Barry’s, Philosophical Thinking about Death and Dying

Vincent Barry is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Bakersfield College, having taught there for thirty-four years. He received his M.A. in philosophy from Fordham University and has been a successful textbook author. In his college textbook, Philosophical Thinking about Death and Dying, Barry carefully considers the question of the relationship between life, death, and meaning.

Is Death Bad? – One of Barry’s main concerns is whether death is or is not bad for us. As he notes, the argument that death is not bad derives from Epicurus’ aphorism: “When I am, death is not; and when death is, I am not.” Epicurus taught that fear in general, and fear of the gods and death in particular, was evil. Consequently, using reason to rid ourselves of these fears was a primary goal of his speculative thinking. A basic assumptions of his thought was a materialistic psychology in which mind was composed of atoms, and death the dispersal of those atoms. Thus death is not then bad for us since something can be bad only if we are affected by it; but we have no sensation after death and thus being dead cannot be bad for us. Note that this does not imply that the process or the prospect of dying cannot be bad for us—they can—nor does Epicurus deny that we might prefer life to death. His argument is that being dead is not bad for the one who has died.

Epicurus’ argument relies on two separate assumptions—the experience requirement and the existence requirement. The experience requirement can be summarized thus:

A harm to someone is something that is bad for them.

For something to be bad for someone it must be experienced by them.

Death is a state of no experience.

Therefore death cannot be bad for someone.

The existence requirement can be summarized thus:

A person can be harmed only if they exist.

A dead person does not exist.

Therefore a dead person cannot be harmed.

As we will see, counter arguments attack one of the two requirements. Either they try to show that someone can be harmed without experiencing the harm, or that someone who is dead can still be harmed.

One noted philosopher who attacks the Epicurean view is Thomas Nagel. In his essay “Death,” Nagel argues that death is bad for someone who dies even if that person does not consciously survive death. According to this deprivation theory, death is bad for persons who die because of the good things their deaths deprive them of. However, if death is bad because it limits the possibility of future goods, is death not then good in limiting the possibility of future evils? So the possibility of future goods does not by itself show that death is bad; to show that one would have to show that a future life would be worth living, that is, that it would contain more good than bad. But how can any deprivation theory explain how it is bad for us to be deprived of something if we do not experience that deprivation? How can what we don’t know hurt us?

In reply Nagel argues that we can be harmed without being aware of it. An intelligent man reduced to the state of infancy by a brain injury has suffered a great misfortune, even if unaware of, and contented in, his injurious state. Nagel argues that many states that we do not experience can be bad for us—the betrayal of a friend, the loss of reputation, or the unfaithfulness of a spouse. And just as an adult reduced to infancy is the subject of a misfortune, so too is one who is dead. But critics wonder who it is that is the subject of this harm? Even if it is bad to be deprived of certain goods, who is it that is deprived? How can the dead be harmed? There apparently no answer to this question.

And there is another problem. While the deprivation argument may explain why death is bad for us, it follows from it that being denied prenatal existence would also be bad. Yet we do not ordinarily consider ourselves harmed by not having been born sooner. How can we explain this asymmetry?

Epicurus argued that this asymmetry could not be explained, and we should feel indifferent to death just as we do to prenatal existence. This sentiment was echoed by Mark Twain:

Annihilation has no terrors for me, because I have already tried it before I was born—a hundred million years—and I have suffered more in an hour, in this life, than I remember to have suffered in the whole hundred million years put together. There was a peace, a serenity, an absence of all sense of responsibility, an absence of worry, an absence of care, grief, perplexity; and the presence of a deep content and unbroken satisfaction in that hundred million years of holiday which I look back upon with a tender longing and with a grateful desire to resume when the opportunity comes.

In reply, deprivationists argue that we do not have to hold symmetrical views about prenatal and postnatal experience—claiming instead that asymmetrical views are consistent with ordinary experience. To see why consider the following. Would you rather have suffered a long surgical operation last year or undergo a short one tomorrow? Would you rather have had pleasure yesterday, or pleasure tomorrow? In both cases we have more concern with the future than the past; we are less interested in past events than in future ones. Death in the future deprives us of future goods, whereas prenatal nonexistence deprived us of past goods about which we are now indifferent. For all these reason Barry concludes that death is probably bad and a fear of death rational. But does death undermine meaning?

The Connection Between Death and Meaning – Tolstoy and Schopenhauer claimed that death makes life meaningless; Russell and Taylor believe that death detracts greatly from the meaning of life, and Buddha argued that death undermines the good things of life. All thought death conflicts with meaning in some sense. Opponents argue that death makes life meaningful. No matter what side they are on, all these thinkers believe that death is the crucial element for determining the extent to which life is, or is not, meaningful.

While there are many arguments that death makes life meaningless, there are also many philosophical arguments, in addition to religious ones, that death makes life meaningful. These latter arguments all coalesce around the idea that death is necessary for a life to be truly human. They take a variety of forms.

Death as necessary for life – There is no development in life without death. Death is happening to you because the universe is happening to you; while you live you are slowly being destroyed. The universe produces life through death so that, while death may be bad for you individually, it is good for the whole.

Death as part of the life cycle – Without the life cycle our experience of being human would be altered. Death is the goal of life, we are programmed to die; it is part of the continuum of life.

Death as ultimate affirmation – Facing death we realize the ultimate value of life; so death has meaning in revealing this value. In addition life is valuable because it is fleeting, fragile, and temporary.

Death as motive to commitment and engagement – Without the finitude of life we would be less motivated to do worthwhile things, and besides immortality may be boring.

Death as stimulus to creativity – Some argue that the nearness of death focuses them to be creative as never before. Others argue that death literally promotes creativity, which emanates from our desire to overcome mortality.

Death as socially useful – Death is necessary to limit overpopulation. Many disagree, arguing that if we lived longer or were immortal we would worry more and be more concerned about the world we live in.

In opposition to all those who think death does or does not give meaning to life are those who argue that life has or lacks meaning independent of death. In other words, they argue that life gives or does not give meaning to death, thereby turning all our previous considerations upside down. But how does a life give or not give death a meaning?

Death and the Meaning of Life – Barry argues that things close to us provide clear answers about meaning—caring for our families, our work, or some cause that is important to us. But when we move to the larger picture and ask about the meaning of everything, we are perplexed. Some speculate that individuals are related to something larger, like a god or a universal plan of which they are part, and that this gives their lives meaning; others that they create or discover meaning in the world without positing a supernatural realm. Such views, as we have seen, are divided between theistic and non-theistic positions. The main problem with the former position is that most contemporary philosophers doubt religious stories are true; the basic problem with the latter is that we are probably mistaken when we imbue an indifferent universe with meaning. Even the notion of progress is insufficient to ground meaning. Such concerns lead Barry to re-examine nihilism.

As we saw previously there are multiple responses to nihilism—we can reject, accept, or affirm it. Yet none of these responses appear adequate; the challenge of nihilism cannot be fully met. Where does this leave us? Barry concludes that though life has no meaning in the objective sense, it still can be meaningful subjectively; it still can be worth living. While persons differ as to how to give their lives meaning and value, Barry maintains that all meaningful lives are examined ones. And that is why the life of Ivan Ilyich lacked meaning—he had not examined his life or his death. Meaningful lives are those that include deep thinking about death and dying. So it seems that death is at least good in this regard. As Barry puts it:

Yes, an individual life can be worthwhile even though life itself may have no ultimate meaning. But only if that life is examined, still resonates the venerable admonition of Socrates borne on the face of the dead Ivan Ilyich—which is to say, only if that life includes philosophical thinking about death and dying.

Summary – It is uncertain if death is a good or bad thing. The connection between death and meaning is that thinking about death can make a life subjectively meaningful.

_____________________________________________________________________

Vincent Barry, Philosophical Thinking About Death and Dying (Belmont CA.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007), 250.

January 7, 2016

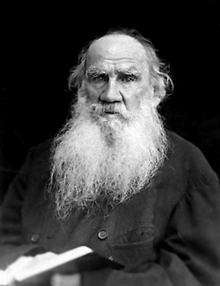

Summary of Tolstoy’s, The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Leo Tolstoy’s short novel,The Death of Ivan Ilyich, provides a great introduction to connection between death and meaning. It tells the story of a forty-five year old lawyer who is self-interested, opportunistic, and busy with mundane affairs. He has never considered his own death until disease strikes. Now, as he confronts his mortality, he wonders what his life has meant, whether he has made the right choices, and what will become of him. For the first time he is becoming … conscious.

The novel begins a few moments after Ivan’s death, as family members and acquaintances have gathered to mark his passing. These people don’t understand death, because they cannot really comprehend their own deaths. For them death is something objective which is not happening to them. They see death as Ivan did all his life, as an objective event rather than a subjective existential experience. “Well isn’t that something—he’s dead, but I’m not, was what each of them thought or felt.” They only praise God that they are not dying, and immediately consider how his death might be to their advantage in terms of money or position.

The novel then takes us back thirty years to the prime of Ivan’s life. He lives a life of mediocrity, studies law, and becomes a judge. Along the way he expels all personal emotions from his life, doing his work objectively and coldly. He is a strict disciplinarian and father figure, the quintessential Russian head of the household. Jealous and obsessed with social status, he is happy to get a job in the city where he buys and decorates a large house. While decorating he falls and hits his side, an accident that will facilitate the illness that eventually kills him. He becomes bad tempered and bitter, refusing to come to terms with his own death. As his illness progresses a peasant named Gerasim stays by his bedside, becoming his friend and confidant.

Only Gerasim shows sympathy for Ivan’s torment—offering him kindness and honesty—while his family thinks that Ivan is a bitter old man. Through his friendship with Gerasim Ivan begins to look at his life anew, realizing that the more successful he became, the less happy he was. He wonders whether he has done the right thing, and comprehends that by living as others expected him to, he may not have lived as he should. His reflection brings agony. He cannot escape the belief that the kind of man he became was not the kind of man he should have been. He is finally experiencing the existential phenomenon of death.

Gradually he becomes more contented and begins to feel sorry for those around him, realizing that they are too involved in the life he is leaving to understand that it is artificial and ephemeral. He dies in a moment of exquisite happiness. On his deathbed: “ It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false.”

Tolstoy’s story forces us to consider how painful it is to reflect on a life lived without meaning, and how the finality of death seals any possibility of future meaning. If, when we approach the end of our lives, we find that they were not meaningful—there will be nothing we can do to rectify the situation. What an awful realization that must be. It was as if Kierkegaard had Ilyich in mind when he said:

This is what is sad when one contemplates human life, that so many live out their lives in quiet lostness … they live, as it were, away from themselves and vanish like shadows. Their immoral souls are blown away, and they are not disquieted by the question of its immortality, because they are already disintegrated before they die.

Now consider an even more chilling question. What difference would it make if the life one lived had been meaningful? Wouldn’t death erase most, if not all, of its meaning anyway? Wouldn’t it be even more painful to leave a life of meaningful work and family? Perhaps we should live a meaningless life to reduce the pain we will feel when leaving it?

Summary – Confronting the reality of death forces us to reflect on the meaning of life.

____________________________________________________________________

Soren Kierkegaard, “Balance between Esthetic and Ethical,” in Either/Or, vol. II, Walter Lowrie, trans., (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1944).

January 6, 2016

Tennyson’s “Tears Idle Tears”

Alfred Lord Tennyson is one of my favorite poets. I think that Tears, Idle Tears” is his most moving poem about longing for a past that we can’t recapture, and the melancholy this elicits. The poem was inspired by a visit to Tintern Abbey in Monmouthshire, which was abandoned in 1536. (William Wordsworth’s poem “Tintern Abbey” was also inspired by this location.)

[image error]

Tintern Abbey

While Tennyson’s visit may have prompted the poem, scholars think he must have had more in mind than just an abandoned abbey. His rejection by Rosa Baring and her family may have played a part in the sadness of the poem. Her family disapproved of her relationship with the son of an alcoholic clergyman. This may explain lines like, “kisses . . . by hopeless fancy feign’d/on lips that are for others” and “Deep as first love, and wild with all regret” which have little to do with Tintern Abbey.

But whatever prompted these beautiful lyrics all of us have looked out over a field, mountain or a lake, an old school, home or neighborhood, or have simply been alone with one’s thoughts and felt the longing for the past which, in retrospect, was fleeting and ephemeral. What was so real then has now receded into oblivion, as will also the minds that have those rich memories.

Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean,

Tears from the depth of some divine despair

Rise in the heart, and gather to the eyes,

In looking on the happy autumn-fields,

And thinking of the days that are no more.

Fresh as the first beam glittering on a sail,

That brings our friends up from the underworld,

Sad as the last which reddens over one

That sinks with all we love below the verge;

So sad, so fresh, the days that are no more.

Ah, sad and strange as in dark summer dawns

The earliest pipe of half-awaken’d birds

To dying ears, when unto dying eyes

The casement slowly grows a glimmering square;

So sad, so strange, the days that are no more.

Dear as remembered kisses after death,

And sweet as those by hopeless fancy feign’d

On lips that are for others; deep as love,

Deep as first love, and wild with all regret;

O Death in Life, the days that are no more!

[image error]

Alfred Lord Tennyson

January 5, 2016

A Harvard Medical School professor makes the case for philosophy

In a recent op-ed in the Washington Post Dr. David Silbersweig made the case for the value of a liberal arts education and in particular a philosophy education. Dr. Silbersweig is the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Co-Director of the Institute for the Neurosciences at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Stanley Cobb Professor of psychiatry and Academic Dean at Harvard Medical School. As a professional philosopher I found his piece interesting and I’d like to summarize his piece and comment on it.

Silbersweig begins by remembering how much he enjoyed being an undergraduate philosophy major and how philosophy,

has informed and provided a methodology for everything I have done since. If you can get through a one-sentence paragraph of Kant, holding all of its ideas and clauses in juxtaposition in your mind, you can think through most anything. If you can extract, and abstract, underlying assumptions or superordinate principles, or reason through to the implications of arguments, you can identify and address issues in a myriad of fields.

Originally drawn to issues in the philosophy of mind, he quickly realized that he needed to study the brain to understand the mind. And wanting to help those who suffered mentally, he realized the need to study medicine. Philosophy had led him to his profession. Moreover his interest in Eastern philosophy, “with its focus on the development of the mind to achieve well-being” led him to study behavioral neuroscience and eventually to the study of both psychiatry or neurology.

Further study abroad confirmed that specialists “without a liberal arts foundation, while often brilliant, generally had a narrower perspective.” But those with such foundations had “certain insights and nimbleness of thought” that those whose training was more vocation did not. Now Silbersweig has come full circle. “Through studies, writings, and symposia, I have been able to bring the knowledge and perspective of my fields to timeless and timely problems in philosophy of mind, including free will, consciousness, meaning, religious experience and self.”

His recent experience teaching “an advanced philosophy of mind seminar at Harvard,” led to the realization of how much his scientific training aided students who asked posed sophisticated philosophical questions but who “were unknowingly misguided by virtue of being under-informed by data.” So philosophical inquiry is valuable, especially if scientific truth informs it. To solve the most desperate problems facing our world, we need minds that find novel solutions, mind informed by both philosophy and science. As Silbersweig concludes:

We need to foster and protect academic environments in which a broad, integrated, yet still deep education can flourish. They are our national treasure and a strategic asset, whether some politicians would recognize that, or not — and philosophy is foundational, whether my old dentist would appreciate it or not.

Reflections – All of this reminds me of lessons I learned from my mentor in graduate school, Richard J. Blackwell. Professor Blackwell told me that philosophy was crucial but must be informed by scientific knowledge. Professor Blackwell had done graduate work in both philosophy and physics. Dr. Silbersweig piece also reminded my of the work of Jean Piaget, who in Insights and Illusions of Philosophy wrote this:

It was while teaching philosophy that I saw how easily one can say … what one wants to say … In fact, I became particularly aware of the dangers of speculation … It’s a natural tendency. It’s so much easier than digging out facts. You sit in your office and build a system. It’s wonderful. But with my training in biology, I felt this kind of undertaking was precarious.1

Philosophical speculation can raise questions, but it cannot provide answers; answers are found only in testing and experimentation. Knowledge presupposes verification, and verification attains only by mutually agreed-upon controls. Unfortunately, philosophers do not usually have experience in inductive and experimental verification.

Young philosophers because they are made to specialize immediately on entering the university in a discipline which the greatest thinkers in the history of philosophy have entered only after years of scientific investigations, believe they have immediate access to the highest regions of knowledge, when neither they nor sometimes their teachers have the least experience of what it is to acquire and verify a specific piece of knowledge.2

But how did it happen that philosophy, which gave birth to the sciences, became so separate from the scientific method? Piaget traces this separation to the 19th century, when philosophy came to believe that it possessed a “suprascientific” knowledge. This split was disastrous for philosophy, as it retreated into its own world, lost its hold on the intellectual imagination, and had its credibility questioned. For Piaget, philosophy is synonymous with science or reflection upon science, and philosophy uniformed by science cannot find truth; at most it provides subjective wisdom. In fact philosophy is not even about truth; at most it is about meaning and values.

But while philosophical speculation without scientific understanding is limited, so too is vocational or scientific understanding uninformed by great philosophical understanding, philosophical questions, and philosophical reflection. And this is ultimately Silbersweig’s point. One can take blood pressure or perform surgery as a mere technician. But medicine, like so many fields, develops when open minds think and see anew. When they philosophize. I am happy to have lived a life in which thinking played a significant role.

January 4, 2016

Commentary on the Idea of an Objective Meaning of Life

(This post summarizes and comments on the posts of the last two weeks. For further details please consult those posts.)

Ellin’s suggestion that the moral life provides meaning is fruitful, as is Thomson’s suggestion that we add intellectual and aesthetic value for fully meaningful lives. But Britton’s comment that all these values may be necessary for meaning but not sufficient is telling. We could live virtuous lives and still question life’s meaningfulness. Yet Britton affirms that life is meaningful because there are meaningful relationships, and Eagleton furthers that claim with his emphasis on love of our fellows and the subsequent happiness derived as the meaning of life. Schlick’s emphasis on play adds greatly to our conception of the meaningful life. Such a life does not have to be infused with undo profundity, but with the playful attitude of the child. So truth, goodness, beauty, love, and play provide a nice list of the objective goods that provide meaning.

Wolf combines subjective engagement with the objective values of the moral, intellectual, and artistic domains. It is not enough that there are valuable things in life; one must be engaged in and passionate about their pursuit to fully achieve meaning. Cahn offers a subjectivist account of value against Wolf, but hedges his bet by introducing an objective value—bringing no harm. We might combine Cahn’s view with Wolf’s and say that meaningful lives consist of active engagement in projects that do no harm. Wolf then could grant the no harm clause as a minimum, but add that lives are even more meaningful if engaged in worthwhile projects that help others. To resolve this issue we probably need a resolution to the problem of the objectivity of value, and Wolf admits as much in her follow up lecture. Meaning itself must be some kind of objective value.

Rachels is confident that there are objective values. These values give us reasons to live in certain ways and provide limited meaning and consolation in a universe where we are always haunted by the specter of death and meaninglessness. Flanagan evokes a similar theme, focusing specifically on self-expression and self-transcendence that follow from things like our work and relationships. Frankl’s emphasizes objective ways to find meaning that are becoming familiar—relationships and work. His addition of bearing suffering is a unique contribution to ways of finding meaning in the world. Belshaw reiterates the theme that we find meaning in our lives in objective goods; and we should not ask what meaning objectively good things have, for that involves us in an infinite regress. To all of the above, Belliotti adds that leaving a legacy of our encounter with the meaning-providers of life contributes greatly to our search for meaning. Thagard takes us into new territory, connecting the objective values of love, work, and play to psychology and neurophysiology in order to explain why we experience meaning in these ways. Finally, Metz clarifies the essence of the ideas of most of these thinkers. Life is meaningful because there are good, true, and beautiful things in the world.

When considering these thinkers together we should note the consistency of thinking about the issue of meaning. There is great unanimity that personal relationships, productive work, and enjoyable play are meaningful activities. They are meaningful precisely because in each we may discover or create goodness, beauty, and truth. Enduring suffering nobly, self-expression, and leaving a legacy also exemplify specific activities that allow us to participate in truth, beauty, and goodness Together these thinkers disclose a universal theme. People find meaning in life by their involvement with, connection to, and engagement in, the good, the true, and the beautiful. We should be satisfied.

Yet we are not. There is another voice within, another perspective that cannot be stilled. After Gandhi, after Beethoven, after Einstein; after helping the unfortunate, playing our games, loving our family, bearing our suffering, and leaving our legacy—it still asks: is that all there is? Perhaps this is a voice that should be silenced, but if these meaningful things are themselves ephemeral, we cannot help but wonder if they really give meaning. The voice within cannot and should not be quieted. We can accept that these good things exist—and want more. There may be good things in the world, and we may add to that value by our creation, but that is not enough. And the reason that these good things are not enough is that there is a specter that accompanies us always. Everywhere we go, every thought we have, every happiness, every joy, every triumph—it is always with us. There to intrude on every meaningful moment, tainting the truth, the beauty, and the goodness that we experience. It is to the specter of death that we now turn.

January 3, 2016

Thaddeus Metz: “The good, the true, and the beautiful: toward a unified account of great meaning in life”

Thaddeus Metz is Head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. He grew up in Iowa and received his PhD from Cornell University in 1997. After teaching at the University of Missouri-St. Louis for a number of years, he relocated to South Africa in 2004. He is probably the most prolific and thoughtful scholar working today on an analytic approach to the meaning of life, publishing more than a dozen articles on the subject including the entry on the meaning of life in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Metz most recent and summative statement on the topic is found in his 2010 essay: “The good, the true, and the beautiful: toward a unified account of great meaning in life.” Of the good, true, and beautiful, Metz begins by asserting: “I aim to make headway on the grand Enlightenment project of ascertaining what, if anything, they have in common.” Metz asks if there is some single property which makes the moral, the intellectual, and the aesthetic worth admiring or striving for. Put as a question: is there something that the lives of a Gandhi, Darwin, or Beethoven might share that are admirable and worthwhile and which thereby confer great meaning to their lives?

In his search for “a unification of moral achievement, intellectual reflection, and aesthetic creation,” Metz does not explore that a god’s purposes unify the triad or that the long term consequences of the triad give meaning to life for a simple reason—we are more justified in thinking that one of the triad gives life meaning that we are in thinking that a god exists or that moral, intellectual or aesthetic activity will have good long-term consequences. Given this disparity in our epistemic confidence, we should not hold that our triad is grounded in the gods or consequences.

Instead Metz focuses on a “non-consequentialist naturalism, the view that the good, the true, and the beautiful confer great meaning on life (at least partly) insofar as they are physical properties that have a superlative final value obtaining independently of their long-term results.” In other words, ethical, intellectual, and aesthetic actions leading to certain accomplishments are intrinsically worthwhile. And the reason is that such actions make it possible for individuals to transcend themselves. But how do moral, intellectual, and artistic activities allow for self-transcendence and, simultaneously, give meaning? Metz answers by distinguishing seven consequentialist, naturalistic theories of self-transcendence that account for how it is that moral achievement, intellectual reflection, and aesthetic creation provide meaning. He lists them from weakest to strongest and explains why each fails. He then proceeds to present his own account.

The first and weakest self-transcendent account of meaning is captivation by an object. The good, true and the beautiful confer meaning by shifting the focus from ourselves to something else. One’s total absorption in artistic feeling, moral goodness, or intellectual inquiry is self-transcendence. Yet this account fails for it is not necessary to be absorbed or captivated by an activity for it to be one of moral achievement—working in a soup kitchen—nor is it sufficient since one may be captivated by something trivial or imaginary—like video games.

This leads to second form of self-transcendence, close attention to the real. The good, true and the beautiful confer meaning by shifting the focus from ourselves to some real natural object. The essence of the good, true, and beautiful is found in captivation by the real, physical, and natural. Metz objects citing that absorption on the navel does not provide meaning. Perhaps then we need to be absorbed with real objects which are also valuable.

This consideration leads to third form of self-transcendence, connection with organic unity. The good, true and the beautiful confer meaning by shifting the focus from ourselves to a relationship with a whole that is beyond us. Metz thinks this partially explains the value of helping others, and of having children and relationships, because persons are valuable insofar as they are organic unities. Art also unifies content, form, and technique into a single object. But this account does not explain much of the true. The importance of metaphysics and the natural sciences are not well explained this way. For example, developing a theory of quarks may give meaning to one’s life, but so could developing a theory about anything trivial. Intrinsic value, the conditions constitutive of meaning, does not seem to reduce to organic unity.

This consideration leads to fourth form of self-transcendence, advancement of valuable open-ended goals. The good, true and the beautiful confer meaning to the extent we make progress toward worthwhile states of affair that cannot be otherwise be realized because our knowledge of these states changes as we try to achieve them. The ends of meaningful activities cannot ultimately be achieved precisely because, as the activities evolve, so too do the ends.

Metz is willing to grant that the pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness are open-ended, but he rejects that this open-endedness confers meaning upon them. Ending racial discrimination, painting the Mona Lisa, or discovering evolution confers meaning not because they are open-ended pursuits, but because they are closed-ended as it were. They each accomplished something even though justice, beauty, and truth are still open-ended pursuits. Furthermore, to say that moral achievement, intellectual reflection, or aesthetic creation confer meaning because they progress toward valuable goals begs the question. We want to know what makes such things meaningful, so it does no good to simply state that they are valuable. We want to know how the good, true, and beautiful confer meaning.

These considerations lead to the fifth form of self-transcendence, using reason to meet standards of excellence. The good, the true, and the beautiful confer meaning in life when we transcend our animal nature with our rational nature to meet certain objective criteria. And we must exercise our reason in exemplary ways to gain meaning. But what are these standards of excellence? What rational activities using reason satisfy the criteria? Why not exercise reason for fiendish ends, as in criminal pursuits?

These questions lead to the sixth form of self-transcendence, using reason in creative ways. The good, the true, and the beautiful confer meaning in life insofar as we transcend our animal nature with our rational nature in creative ways. Life is redeemed through the creative power of artists and thinkers who bring new values into the world. Yet this theory still has trouble accounting for the apparent meaninglessness of the creative criminal. It also cannot account for moral virtue, which often has nothing to do with creativity.

These questions lead to the seventh form of self-transcendence, using reason according to a universal perspective. The good, the true, and the beautiful give meaning to life when we transcend our animal nature by using our rational nature to realize states of affairs that would be appreciated from a universal perspective. Art, scientific theories, and moral deeds all satisfy this criterion. Great art reveals universal themes; great science discovers universal laws; and great moral deeds take everyone’s interests into account and are approved of from an impartial perspective. Metz considers this the best account of a self-transcendent theory of meaning. Yet it is inadequate because much that could be approved of from this universal perspective would be trivial and not the source of great meaning—writing a novel about dust or distributing implements for toenail cutting.

Having surveyed various naturalistic and non-consequentialist theories that tried to capture how the good, true, and beautiful give meaning to life, and having found them wanting, Metz proposes his own theory of self-transcendence: “The good, the true, and the beautiful confer great meaning on life insofar as we transcend our animal nature by positively orienting our rational nature in a substantial way toward conditions of human existence that are largely responsible for many of its other conditions.”

Metz explains this focus on fundamental conditions by considering the difference between a well-planned crime and moral achievements such as providing medical care or freeing persons from tyranny. The latter actions respect personal autonomy, support other’s choices and confer meaning. Intellectual reflection that gives meaning explains many other facts and conditions about human nature or reality. Knowledge of human nature tells us about aspects of ourselves, as scientific knowledge about the world explains reality. Similarly great art is about facets of human experience—love, death, war, peace—which are themselves responsible for so much else about us. In each case meaning derives when the true, good, and beautiful address fundamental issues.

One might object that reading trashy fiction or pondering that

2 + 2 = 4 involve reason and focus on fundamental conditions, but don’t confer meaning. Metz replies that substantial effort is necessary to fully meet his standard, and that is missing in the above examples. In addition we might add that significant advancement over the past is also necessary for meaning. Not simply doing, knowing, or making what was done, known, or made before, but the bringing forth of something new. All of this leads to his conclusion: that we can transcend ourselves and obtain great meaning in the good, the true, and the beautiful “by substantially orienting one’s rational nature in a positive way toward fundamental objects and perhaps thereby making an advancement.”

Summary – Meaning is found by transcending oneself through moral achievement, intellectual reflection, and artistic creation.

Thaddeus Metz, “The Good, the True and the Beautiful: Toward a Unified Account of Great Meaning in Life.” DOI: 10.1017/S0034412510000569. 1. Cambridge Online 2010, 1.

Metz, “The Good, the True and the Beautiful: Toward a Unified Account of Great Meaning in Life.” 2.

Metz, “The Good, the True and the Beautiful: Toward a Unified Account of Great Meaning in Life.” 3.

Metz, “The Good, the True and the Beautiful: Toward a Unified Account of Great Meaning in Life.” 13.

Metz, “The Good, the True and the Beautiful: Toward a Unified Account of Great Meaning in Life.” 19.

Chapter 7

January 2, 2016

Review of Paul Thagard’s, The Brain and the Meaning of Life

Paul Thagard (1950 – ) is professor of philosophy, psychology, and computer science and director of the cognitive science program at the University of Waterloo in Canada. His recent book, The Brain and the Meaning of Life (2010), is the first book length study of the implications of brain science for the philosophical question of the meaning of life.

Thagard admits that he long ago lost faith in his childhood Catholicism, but that he still finds life meaningful. Like most of us, love, work, and play provide him with reasons to live. Moreover, he supports the claim that persons find meaning this way with evidence from psychology and neuroscience. (He is our first writer to do this explicitly.) Thus his approach is naturalistic and empirical as opposed to a priori and rationalistic. He defends his approach by noting that thousands of years of philosophizing have not yielded undisputed rational truths, and thus we must seek empirical evidence to ground our beliefs.

While neurophysiology does not tell us what to value, it does explain how we value—we value things if our brains associate them with positive feelings. Love, work, and play fit this bill because they are the source of the goals that give us satisfaction and meaning. To support these claims, Thagard notes that evidence supports the claim that personal relationships are a major source of well-being and are also brain changing. Similarly work also provides satisfaction for many, not merely because of income and status, but for reasons related to the neural activity of problem solving. Finally, play arouses the pleasures centers of the brain thereby providing immense psychological satisfaction. Sports, reading, humor, exercise, and music all stimulate the brain in positive ways and provide meaning.

Thagard summarizes his findings as follows: “People’s lives have meaning to the extent that love, work, and play provide coherent and valuable goals that they can strive for and at least partially accomplish, yielding brain-based emotional consciousness of satisfaction and happiness.”

To further explain why love, work, and play provide meaning, Thagard shows how they are connected with psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Our need for competence explains why work provides meaning, and why menial work generally provides less of it. It also explains why skillful playing gives meaning. The love of friends and family is the major way to satisfy our need for relatedness, but play and work may do so as well. As for autonomy, work, play, and relationships are more satisfying when self-chosen. Thus our most vital psychological needs are fulfilled by precisely the things that give us the most meaning—precisely what we would expect.

Thagard believes he has connected his empirical claim the people do value love, work, and play with the normative claim that people should value them because these activities fulfill basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Our psychological needs when fulfilled are experienced as meaning.

Summary – Love, work, and play are our brains way of satisfying our basic needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. In the process of engaging in these activities, we find meaning.

____________________________________________________________________

Paul Thagard, The Brain and the Meaning of Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 165.

January 1, 2016

Summary of Raymond Belliotti’s, What is the Meaning of Human Life?

Raymond Angelo Belliotti is Distinguished Teaching Professor of Philosophy SUNY Fredonia. He holds a PhD in philosophy from the University of Miami and a J.D. from Harvard University.

Belliotti’s book What Is The Meaning Of Human Life? (2001) advances an objective naturalist approach to meaning. He begins by addressing the bearing of theistic belief for meaning and concludes that for those who truly believe doubts vanish and the meaning of life is clear. “Charitably interpreted, theism can fulfill the deepest human yearnings.” The problem is that belief is hard to maintain and doubt hard to swallow. In short, belief requires a leap of faith that many will resist. Yet he finds nihilism even less compelling. It is just not true that life is pointless. Meaning is possible, and the process of creating it satisfies most of us at least some of the time. Still, the question of life’s meaning continually intrudes, becoming most acute in times of psychological crisis. As for subjective accounts of meaning, they are deflationary, providing a starting point in the search for meaning but not the robust meaning that most desire. Believing one’s life has meaning does not make it so.

These considerations lead to a kind of philosophical paralysis, especially when our lives our viewed from the cosmic perspective. Adopting the cosmic perspective we might conclude that the cosmos and our lives lack meaning, that we are limited, insignificant, and impermanent. In response numerous strategies are available. One would be to accept that meaningful lives don’t require significance from a cosmic perspective but only from a human perspective. One could lower the bar that needs to be reached in order to call a life meaningful. Another might use the cosmic perspective to help put things in perspective, to take ourselves less seriously, and to view our sufferings as less grave. Used creatively the cosmic perspective can help us. Thus we should oscillate between perspectives, using whichever one aided us at the moment. If we want to feel vibrant in the moment, savoring our current achievements, we could adopt the personal perspective. If we want to reflect on our situation from afar, we could adopt the cosmic perspective. So we can maximize happiness and minimize suffering by deftly switching perspectives.

This discussion of perspectives shows that meaning is connected with consciousness, freedom, and creativity. The more these attributes adhere to a being, the greater the possibility of meaning. Thus meaning is not out there waiting to be discovered, the individual must contribute to its creation. Still, we cannot create meaning out of nothing, but only from our interaction with objects of value. This takes us back to the familiar discussion of objective values. Belliotti argues that engaged lives concerned with freely chosen trivial values count as minimally meaningful. Thus a meaningful life does not have to be significant or important, but fully meaningful lives are both—significant because they influence other people, and important because they made a difference in the world. And to be valuable a life must produce moral, intellectual, aesthetic, or religious value. Value is the most important attribute of meaningful lives. Of course most of us don’t live robustly meaningful lives because our lives are not valuable as thus defined, but they can be meaningful to a lesser extent by being important or significant.

Talk of valuable lives leads Belliotti to the idea of leaving historical footprints or legacies. For example, we think of Picasso’s life as valuable and robustly meaningful for the reason that it left a legacy of artwork independent of whatever moral shortcoming he may had. A legacy does not grant us immortality but it does give meaning to our lives by tying us to something beyond ourselves. Dedicated service to our community or commitment to rearing children are classic examples of intense labor that points beyond ourselves and gives so many lives meaning. We can always bemoan our insignificance from a cosmic perspective, but why should we? Meaning is found by standing in relationship to things and people of value, importance, and significance. In simple terms by having fulfilling relationships and appreciating music, literature, and philosophy, as opposed to watching television or engaging in small talk.

In the end we must love life and the world; we must love the valuable things of this world to find meaning in it. Often our habits and the diversions of life obscure our search for meaning, but we can come back to it. With joyous engagement in and relationship to valuable things and people of this world, we can live meaningful lives, and leave some trace of that encounter as our legacy.

Summary – We find meaning in relationship with persons and the objective values of this world, and leaving a legacy if possible.

Raymond Belliotti, What is the Meaning of Human Life? (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001), 29.

December 31, 2015

Christopher Belshaw’s, 10 Good Questions about Life and Death

Christopher Belshaw is a Senior Lecturer in philosophy at the Open University. He received his PhD from the University of California-Santa Barbara. In his 2005 book, 10 Good Questions About Life And Death, he devotes a chapter to the question “Is It All Meaningless?”

Belshaw argues that those who seek meaning are concerned that life does not have one. They think either that their own life or all life lacks a point, purpose or significance. Some reasons we might think life meaningless include: a) the brevity of our lives; b) the smallness of life compared with the vastness of the universe; c) the pain and suffering of life; or d) that there are no gods with a master plan.

But are these good reasons to think life meaningless? Belshaw thinks not. The last argument only follows if there are no gods, and lots of people believe the opposite. As for the claim that life is full of suffering, we might retort that it is full of satisfaction as well. It is hard to challenge the fact that we are small and the universe vast, but is that really significant? Why would life be more meaningful if the universe were smaller or we were bigger? And why would it make a difference for meaning that humans continue to exist forever? These replies lead Belshaw to believe that we don’t want meaning per se, such as fitting into something else’s scheme, but our own meaning and purpose. He suggests we change the focus of our question from the meaning of life in general to that of our individual lives. And he rejects a singular answer in favor of considering various things as giving life meaning. In this way we can make progress in answering our question.

Now the first suggestion is that meaning is up to you; meaning is entirely subjective. Belshaw dismisses this with a thought experiment. If someone claims they live a meaningful life by trying to make their plants sing then, though they may be happy, they are living a pointless and foolish life. You cannot make a life meaningful simply by believing it to be. After all plants don’t sing! Or you might be happy as a drug addict, but we would still judge your life to be a waste.

If the subjective approach work, what about the objective approach? Belshaw says that the things that matter are relationships, projects, and morally good living. If we really love others, share their pleasures and pains, their hopes and aspirations, it is hard to believe that our lives are insignificant. If we have a project that means something to us—to build a house, write a book, see the world—this fits poorly with the notion that our lives are meaningless. And if we seek to help others and make the world a better place, such a life such will not seem meaningless. Moreover, these points are connected. Involvement with others gives rise to projects, and projects involve you with other people. Living a moral life does something similar. All of these activities are held together by giving our temporal lives a constructive, creative, and ultimately meaningful dimension.

But on reflection the objective approach seem to work either. Our moral lives and our projects don’t seem to be meaningful if we are not engaged in them. So your attitude, although not sufficient to meaning, does seem necessary.

But even if there are ways to live which are better than others, does it matter in the end? Belshaw counters that the fate of the universe is independent of whether it matters that people suffer, and likewise for the more mundane matters in our lives. Things matter to us and the fate of the universe is irrelevant. You might object that such things don’t really matter but this is no different than plain mattering. If something matters, then it does. The idea of ultimately mattering does not really make sense. Once you ask for the meaning of the meaning, you are involved in an infinite regress—there will be no way to end the search for the ultimate meaning. And yet, although we can view our lives as meaningful from the inside, the external perspective continually reappears. Should we just accept our lives as absurd then? Belshaw says no. The ordinary things in our lives are important even if they don’t change the history of the universe, and there is no inconsistency in this recognition. Life is not absurd.

Should we then be concerned with meaning? Many in the past have not been concerned about it, and Belshaw argues that our current concern emanates from the twentieth century existentialists. The question is not necessarily one of perennial concern. If we consider the life of a typical person that works, gets married, raises a family, and has a little fun, it is not especially meaningful but it is not meaningless either. Such a person may not be very moral, or have any satisfying relationships or work, but if they find their lives worth living we should let the matter rest there. After all too much about life may not be much help, and a simple life of limited meaning and contemplation is probably best.

Our lives differ by degree in terms of their meaning. The meaning of a life differs depending on what the life is like and what the subject living it thinks about it. As for the meaning of the universe we can say that it probably has no meaning, but Belshaw says this does not matter, since we cannot imagine how the universe could have meaning. Thus we don’t lack anything real when we lack ultimate meaning. Belshaw concludes: “Even if we decide that we can see that, really, there is nothing that it’s all about, that’s alright as well.”

Summary – Relationships, projects, and moral lives are the objectively good things that give our subjective lives meaning. And that is enough, as concerns about the ultimate meaning of everything are unfounded.

________________________________________________________________

Christopher Belshaw, 10 good questions about life and death (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 128.