John G. Messerly's Blog, page 98

December 30, 2015

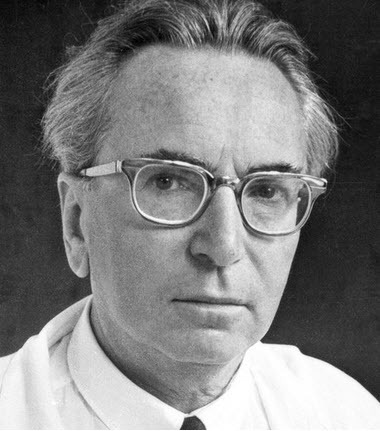

Summary of Victor Frankl’s, Man’s Search for Meaning

Viktor Emil Frankl M.D., PhD. (1905 – 1997) was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist as well as a Holocaust survivor. Frankl was the founder of logo-therapy, a form of Existential Analysis, and best-selling book author of, Man’s Search for Meaning, Gift Edition, which belongs on any list of the most influential books in last half-century. It has sold over 12 million copies. (According to a survey conducted by the Library of Congress and the Book-of-the-Month Club it belongs to “the ten most influential books in America.” (New York Times, November 20, 1991)

The first part of the book tells the story of his life in the concentration camps—needless to say it is not for the faint of heart. Although Frankl survived, his parents, brother, and pregnant wife all perished. (There is no good substitute for a close reading of the book to convey the unrelenting misery of the situation, or to appreciate Frankl’s reflections on it. The record of his personal experience and observation is a priceless cultural legacy.)

Frankl’s philosophical views that emanate from his experience begin with his quoting Nietzsche: “He who has a why to live can bear with almost any how.” If we live to return to our loved ones or to finish our book, if we have a why to live for, if we have a meaning to live for, then we have a reason to survive, no matter how miserable the conditions of our lives. This desire to live, what Frankl calls “the will to meaning,” is the primary motive of human life. Putting these ideas together we are driven by the desires to survive, exist, and find meaning.

Frankl believes that a large part of meaning is subjective. It is not what we expect from life but what it expects from us that will provide meaning. We are free and we are responsible for how we live our lives. In this way Frankl sounds like an existentialist and subjectivist, extolling us to create our own meaning. But we classify him as an objectivist, for in the end there are objective values, there are things in this world that can provide meaning for anyone. The three objective sources of meaning are: 1) the experience of goodness or beauty, or of loving others; 2) creative deeds or work; and 3) the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering. It is easy to see that love or work could give life meaning. If others whom we love depend upon us, or if we have some noble work to finish, we have a meaning for our lives; we have a why for which to bear any how.

But how is the attitude we take toward suffering a potential source of meaning? Frankl says first that we reveal our inner freedom in the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering; and secondly, like the Stoics, we can see our suffering as our task that we can bear nobly. Thus our suffering can be an achievement in which tragedy has been transformed into triumph. Frankl observed that prisoners who changed their attitudes toward suffering in this way were the ones who had the best chance of surviving. In the end Frankl makes a case for tragic optimism. Life may be tragic, but we should remain optimistic that it meaningful nonetheless—life even in its most tragic manifestations provides ways to make life meaningful.

Summary – Meaning in life is found in productive work, loving relationships, and enduring suffering nobly.

December 29, 2015

Owen Flanagan: “What Makes Life Worth Living?”

Owen Flanagan (1949 – ) is the James B. Duke Professor of Philosophy and Professor of Neurobiology at Duke University. He has done work in philosophy of mind, philosophy of psychology, philosophy of social science, ethics, moral psychology, as well as Buddhist and Hindu conceptions of the self.

In his essay, “What Makes Life Worth Living?” Flanagan does not assume “that life is or can be worth living.” Perhaps we are just biologically driven to live worthless lives. So he begins by asking: “Is life worth living?” And if it is then “…what sorts of things make it so?” He notes that reflecting on this question may be a waste of time, as life might be better for the non-reflective. Reflection may lead to despair, if one determines that life is worthless, or to joy, if one concluded to the contrary. The question of whether life is worth living and what makes it so is connected with another bewildering question: “Do we live our lives?” In one sense the answer is obvious—we spend time not dead—but Flanagan wants to know if we act freely or are merely controlled like puppets. So questions about the value of living involve issues about who we are and what kinds of things are true about us.

Flanagan argues that even happiness is not enough to guarantee that life is worthwhile, inasmuch as a life may contain much happiness and still be meaningless. Happiness is not sufficient for meaning, since one might derive happiness from evil things, and it may not be necessary either, since a meaningful life may be devoid of happiness. But even if happiness is a component of a worthwhile life, he argues that identity and self-expression are more crucial. “Wherever one looks, or so I claim, humans seek, and sometimes find worth in possessing an identity and expressing it.” Identity and self-expression are necessary but not sufficient conditions for worthwhile living, since we need to clarify what forms of identity and expressions of it are valuable.

But what if there is no self to find meaning through self-expression? There are three standard arguments supporting the idea that we are not selves. First, maybe I am just a location where things happen from a universal perspective. Second, I may simply be the roles I play in various social niches, with self just a name for this apparent unity. Third, my apparent unity may be just various stages which change as we age. Regarding this last argument, Flanagan concedes that there is no same self continuing over time, but that this does not show there is no self, just that it changes over time. Even granting the second argument that I am a social construction; I am still something, so the death of self does not follow. The first argument suggests determinism; but even if I am determined, I am still an agent who does things. So these death-of-subject arguments, while deflating our view of self, don’t destroy it. Flanagan agrees that humans are contingent and don’t posses eternal souls—but this does not mean they are not subjects.

But why is there anything at all? And why am I one of the things that is? Such questions invite answers such as: 1) the gods decided that the universe and creatures should exist and I have the chance to join them if I follow their commands; or 2) we don’t know why there is anything except to say that the big bang and subsequent cosmic and biological evolution led to me. Flanagan notes that neither answer is satisfactory, because both posit something eternal—gods or physical facts. But that does not answer why there is something rather than nothing. (Reminiscent of earlier claims that we can’t answer ultimate why questions.)

And yet many find the first story comforting, presumably because it links us with transcendent meaning. The second story has less appeal to most since it raises questions about one’s significance, moral objectivity, concept of self, and ultimate meaning. But is the first story really more comforting than the second? How do the gods’ plans make my life meaningful? And if the gods are the origin of all things are they really good? Thus it does not seem that either the theological or scientific story about origins can ground meaning in our lives.

Thus Flanagan suggests that we look elsewhere for meaning. Perhaps a person’s meaning comes from relationships with others, or with work, or from nature—from things we can relate to in this life. After all, the scientific story never says that life does not matter. In fact a lot of things matter to me, from mundane things that I love to do—hiking and travel—to more long term projects that matter even more—learning, loving, and working creatively. This means that we are creatures that thrive on self-expression and, to the extent that we are not thwarted in this desire, can ameliorate the human condition and diminish the tragedy of our demise by this expression. As Flanagan concludes:

This is a kind of naturalistic transcendence, a way each of us, if we are lucky, can leave good-making traces beyond the time between our birth and death. To believe this sort of transcendence is possible is, I guess, to have a kind of religion. It involves believing that there are selves, that we can in self-expression make a difference, and if we use our truth detectors and good detectors well, that difference might be positive, a contribution to the cosmos.

Summary – We find meaning through self expression in our work and in our relationships.

__________________________________________________________________

Flanagan, “What Makes Life Worth Living?” 206.

December 28, 2015

James Rachels on the Meaning of Life

James Rachels (1941- 2003) was a distinguished American moral philosopher and best-selling textbook author. He taught at the University of Richmond, New York University, the University of Miami, Duke University, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where he spent the last twenty-six years of his career.

The final chapter of his book, Problems from Philosophy, explores the question of the meaning of life. (It was written as Rachels was dying of cancer.) Although Rachels admits the question of the meaning of life does come up when one is depressed, and hence can be a symptom of mental illness, it also arises when we are not depressed, and thus mental illness is not a prerequisite for asking the question. He agrees with Nagel that the questions typically results from recognizing the clash between the subjective or personal point of view—from which things matter—and the objective or impersonal view—from which they don’t.

Regarding the relationship between happiness and meaning, Rachel notes that happiness is not well correlated with material wealth, but with personal control over one’s life, good relationships with family and friends, and satisfying work. In Rachels view happiness is not found by seeking it directly, but as a by-product of intrinsic values like autonomy, friendship, and satisfying work. Nonetheless, a happy life may still be meaningless because we die, and in times of reflection we may find our happiness undermined by the thought of our annihilation.

What attitude should we take toward our death? For those who believe they don’t die, death is good because they will live forever in a hereafter. For them death “is like moving to a better address.” But for those who believe that death is their final end, death may or may not be a good thing. What attitude should these people take toward death? Epicurus thought that death was the end but that we should not fear it, since we will be nothing when dead and nothingness cannot harm us. He thought that such an attitude would make us happier while alive. On the contrary, Rachels thinks that death is bad because it deprives us of, and puts an end to, all the good things in life. As Rachels so eloquently puts it:

After I die, human history will continue, but I won’t get to be part of it. I will see no more movies, read no more books, make no more friends, and take no more trips. If my wife survives me, I will not get to be with her. I will not know my grandchildren’s children. New inventions will appear and new discoveries will be made about the universe, but I won’t ever know what they are. New music will be composed, but I won’t hear it. Perhaps we will make contact with intelligent beings from other worlds, but I won’t know about it. That is why I don’t want to die, and Epicurus’ argument is beside the point.

Although death is bad, it does necessarily make life meaningless, inasmuch as the value of something is different than how long it lasts. A thing can be valuable even if it is fleeting; or worthless even if it lasts a forever. So the fact that something ends does not, by itself, negate its value.

There is yet another reason that a happy life might be meaningless—and that reason is that the universe may be indifferent. The earth is but a speck in the inconceivable vastness of the universe, and a human lifetime but an instant of the immensity of time. The universe does not seem to care much for us. One way to avoid this problem is with a religious answer—claim that the universe and a god do cares for us. But how does this help, even if it is true? As we have seen, being a part of another’s plan does not seem to help, nor does being a recipient of the god’s love, or living forever. It is simply not clear how positing gods gives our lives meaning.

Rachels suggest that if we add the notion of commitment to the above, we can see how religion provides meaning to believer’s lives. Believers voluntarily commit themselves to various religious values and hence get their meaning from those values. But while you can get meaning from religious values you can also get them from other things—from artistic, musical, or scholarly achievement for example. Still, the religious answer has a benefit that these other ways of finding meaning don’t; it assumes that the universe is not indifferent. The drawback of the religious view is that it assumes the religious story is true. If it is not, then we are basing our lives on a lie.

But even if life does not have a meaning, particular lives can. We give our lives meaning by finding things worth living for. These differ between individuals somewhat, yet there are many things worth living for about which people generally agree—good personal relationships, accomplishments, knowledge, playful activities, aesthetic enjoyment, physical pleasure, and helping others. Could it nonetheless be that all of this amounts to nothing, that life is meaningless after all? From the objective, impartial view we may always be haunted by the suspicion that life is meaningless. The only answer is to explain why our list of good things is really good.

Such reasoning may not show that our lives are ‘important to the universe,’ but it will accomplish something similar. It will show that we have good, objective reasons to live in some ways rather than others. When we step outside our personal perspective and consider humanity from an impersonal standpoint, we still find that human beings are the kinds of creatures who can enjoy life best by devoting themselves to such things as family and friends, work, music, mountain climbing, and all the rest. It would be foolish, then, for creatures like us to live in any other way.

Summary – Happiness is not the same as meaning and is undermined by death. Death is bad unless religious stories are true, but they probably are not true. Thus, while there is probably no objective meaning to life, there are good things in life. We should pursue those good things that most people think worthwhile—love, friendship, knowledge, and all the rest.

_____________________________________________________________________

Rachels, Problems from Philosophy, 174-75.

December 27, 2015

Susan R. Wolf: The Importance of Objective Values

Susan R. Wolf elaborated on her ideas about meaning in life in two lectures delivered at Princeton in 2007. ( We previously discussed her views two days ago.) There she claimed that meaning is not reducible to either happiness or morality. While philosophers often argue that individual happiness or impersonal duty motivate why people act, Wolf maintains that meaning also motivates action. She thus seeks a middle way between recommendations to “follow your bliss” or “do your duty.”

To explain this she differentiates between the Fulfillment view—that meaning is found in whatever fulfills you—and the Larger-Than-Oneself view—that meaning if found in dedicating yourself to something larger than yourself. The fulfillment view satisfies subjectively but may lack objective value; whereas the larger-than-oneself view suffers from the reverse, it may be objectively meaningful but not subjectively fulfilling. The solution combines the best features of both. Meaningfulness in life thus comes from engaging in, being fulfilled by, and ultimately loving things objectively worthy of love. (The subjective attraction and objective attractiveness she spoke of earlier.) Furthermore, she argues that subjective fulfillment depends on being engaged in the objectively worthwhile—counting cracks on the sidewalk will not do, but pursuing medical research could. Therefore the subjective and objective elements are inextricable linked.

This leads Wolf back to the question of objective meaning. How does one answer Cahn’s objection that meaning is subjective? While Wolf does not provide a theory of objective value, she does claim that there are subject-independent values, since at least some things are valuable to everyone. If this is true then the truth or falsity of whether a life is meaningful is subject-independent, although Wolf defers from assessing the meaningfulness of other’s lives.

The question of meaning is not merely academic then, since answers to it inform individuals about themselves and others. The concept of meaning also has explanatory value, explaining why people do thing for reasons other than self-interest or duty. In short, meaningfulness matters. It may not be the only value, but it is valuable nonetheless. Moreover, the concept of meaning is unintelligible without some notion of objective value, despite the fact that we cannot specify this value with much precision.

Summary – Meaning is a value distinct from both happiness and morality, but it relies on the reality of some objective value, however non-specifically that is defined.

December 26, 2015

Steven Cahn’s “Meaningless Lives?”: A Reply to Wolf

Steven Cahn is Professor of Philosophy at CUNY Graduate Center and the author or editor of many philosophical textbooks. Cahn rejects Wolf’s distinction between meaningful and meaningless lives, arguing that it does not make sense to judge a life meaningful or meaningless. While Wolf does not offer a theory of objective value, she does give examples of activities that are meaningful, some that are meaningless and some that she is uncertain about. Her examples are:

Meaningful activities include: moral or intellectual accomplishments, personal relationships, religious practices, mountain climbing, training for a marathon, and helping a friend.

Meaningless activities include: collecting rubber bands, memorizing the dictionary, making handwritten copies of great novels, riding roller coasters, meeting movie stars, watching sitcoms, playing computer games, solving crossword puzzles, recycling, or writing checks to Oxfam and the ACLU.

Uncertain cases include: a life obsessed with corporate law, being devoted to a religious cult, or being a pig farmer who buys more land to grow more corn to feed more pigs…

Cahn seizes on how controversial these cases are. Why are some meaningful and some not? What about all the other cases she mentions? Is golf a useful way to spend your time? Some think so, others don’t. And even if some activity is mindless and futile, does that mean it is meaningless? Weightlifting may be mindless and futile, but does that make it meaningless? Many might think it meaningless to read articles about the meaning of life, and then write articles about the meaning of life which are in turn read by others. Cahn concludes that lives that don’t harm others should be appreciated as relatively meaningful.

Summary – Meaningful lives consist of finding happiness without doing harm to others.

________________________________________________________________

Steven Cahn, “Meaningless Lives?” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D. Klemke and Cahn (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2008), 236.

December 25, 2015

Summary of Susan Wolf’s, “Happiness and Meaning: Two Aspects of the Good Life”

Susan R. Wolf (1952 – ) is a moral philosopher who has written extensively on the meaning in human life. She is currently the Edna J. Koury Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She addresses the topic of the meaning of life in her essay: “Happiness and Meaning: Two Aspects of the Good Life.”

Wolf maintains that meaningful lives have within them the possibility of answering one’s need for meaning. These needs center on questions of whether life is worth living, has any point, or provides sufficient reason to go on. Paradigms of meaningful lives include lives of moral or intellectual accomplishment, whereas meaningless lives include those lived in quiet desperation or in futile labor. In short, Wolf claims that: “… meaningful lives are lives of active engagement in projects of worth.”

Active engagement refers to being griped or excited by something. Active engagement relates to being passionate rather than alienated about something, whereas being engaged is not always pleasant since it may involve hard work. Projects of worth suggests that some objective value exists, and Wolf argues that meaning and objective value are linked. While Wolf offer a philosophical defense of objective value she claims that “there can be no sense to the idea of meaningfulness without a distinction between more and less worthwhile ways to spend one’s time, where the test of worth is at least partly independent of a subject’s ungrounded preferences or enjoyment.”

To see this point, first consider that people’s longings for meaning are independent of whether they find their lives enjoyable. They may have a fun life but might come to think it lacks meaning. Second, why do we seem to have an intuitive sense of meaningful and meaningless lives? Most of us would agree that certain kinds of lives are or are not meaningful. Both of the above suggest that objective values are related to meaning.

This leads Wolf to reiterate that meaningful lives are ones actively engaged in worthwhile projects. If one is engaged in life, then it has a point; looking for meaning is looking for worthwhile projects. In addition, this view shows us why some projects are thought of as meaningful and others are not. Some projects are meaningful but boring (like writing checks to the ACLU), whereas others are pleasurable (like riding roller coasters) but don’t seem to give meaning to life. In this context, Wolf notes Bernard Williams’ distinction between categorical desires, whose objects are worthwhile independent of our desires; and all other desires, whose objects worthiness, presumably, depends on our desires. In short, she is saying some values are objective.

To reiterate, meaningful lives link active engagement with objectively worthwhile projects. Lives lived without engagement lack meaning, even if what they are doing is meaningful, since the person living such a life is bored or alienated. However, lives lived with engagement are not necessarily meaningful, if the objects of the engagement are worthless, since those objects lack objective value. Wolf summaries her view as follows: “Meaning arises when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness…meaning arises when a subject discovers or develops an affinity for one or typically several of the more worthwhile things…”

Summary – Meaningful lives consist of one’s active engagement with objectively worthwhile things.

__________________________________________________________________

Wolf, “Meaning in Life” 234-35.

Susan Wolf on Meaning in Life

Susan R. Wolf (1952 – ) is a moral philosopher who has written extensively on the meaning in human life. She is currently the Edna J. Koury Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She addresses the topic of the meaning of life in her essay: “”Happiness and Meaning: Two Aspects of the Good Life.”

Wolf maintains that meaningful lives have within them the possibility of answering one’s need for meaning. These needs center on questions of whether life is worth living, has any point, or provides sufficient reason to go on. Paradigms of meaningful lives include lives of moral or intellectual accomplishment, whereas meaningless lives include those lived in quiet desperation or in futile labor. In short, Wolf claims that: “… meaningful lives are lives of active engagement in projects of worth.”

Active engagement refers to being griped or excited by something. Active engagement relates to being passionate rather than alienated about something, whereas being engaged is not always pleasant since it may involve hard work. Projects of worth suggests that some objective value exists, and Wolf argues that meaning and objective value are linked. While Wolf offer a philosophical defense of objective value she claims that “there can be no sense to the idea of meaningfulness without a distinction between more and less worthwhile ways to spend one’s time, where the test of worth is at least partly independent of a subject’s ungrounded preferences or enjoyment.”

To see this point, first consider that people’s longings for meaning are independent of whether they find their lives enjoyable. They may have a fun life but might come to think it lacks meaning. Second, why do we seem to have an intuitive sense of meaningful and meaningless lives? Most of us would agree that certain kinds of lives are or are not meaningful. Both of the above suggest that objective values are related to meaning.

This leads Wolf to reiterate that meaningful lives are ones actively engaged in worthwhile projects. If one is engaged in life, then it has a point; looking for meaning is looking for worthwhile projects. In addition, this view shows us why some projects are thought of as meaningful and others are not. Some projects are meaningful but boring (like writing checks to the ACLU), whereas others are pleasurable (like riding roller coasters) but don’t seem to give meaning to life. In this context, Wolf notes Bernard Williams’ distinction between categorical desires, whose objects are worthwhile independent of our desires; and all other desires, whose objects worthiness, presumably, depends on our desires. In short, she is saying some values are objective.

To reiterate, meaningful lives link active engagement with objectively worthwhile projects. Lives lived without engagement lack meaning, even if what they are doing is meaningful, since the person living such a life is bored or alienated. However, lives lived with engagement are not necessarily meaningful, if the objects of the engagement are worthless, since those objects lack objective value. Wolf summaries her view as follows: “Meaning arises when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness…meaning arises when a subject discovers or develops an affinity for one or typically several of the more worthwhile things…”

Summary – Meaningful lives consist of one’s active engagement with objectively worthwhile things.

__________________________________________________________________

Wolf, “Meaning in Life” 234-35.

December 24, 2015

Summary of Mortiz Schlick, “On the Meaning of Life”

Mortiz Schlick (1882– 1936) was a German philosopher and the founding father of logical positivism and the Vienna Circle. He was shot to death at the University of Vienna by a former student. In 1927 he penned as essay entitled “On the Meaning of Life.”

According to Schlick the innocent or childlike never ask the question of the meaning of life; others, the weary, no longer ask the question because they have concluded that there is none. “In between are ourselves, the seekers.” While some lament that they have not fulfilled the goals of youth and accept that their lives are meaningless, they nevertheless believe that life is meaningful for those who have fulfilled their goals. Others achieve their goals, only to find that this achievement has not provided meaning. So it is hard to see the meaning of life. We set goals and head toward them with hope, but their achievement does not bring meaning. The goals are reached but the desire for new goals follows. There is never satisfaction, and all this longing ends in death. How then to escape all this?

Nietzsche sought to escape this pessimism thru art and then through knowledge, but neither led to meaning. He concluded that if we think of the meaning of life as a purpose, we will never find meaning. If we ask people about their purpose, most persons would say that they are working to maintain life or to stay alive, but pure existence is valueless without content. So we are caught in a circle, working to stay alive, and staying alive to keep working. Work is generally a means to an end, never an end in itself; and though some activities are intrinsically meaningful, like pleasurable ones, they are too fleeting to give life meaning.

In response Schlick argues that meaning is to be found in activities that are intrinsically valuable—where the means and the ends are united; where the means is the end. He quotes Schiller that play is the activity that carries its own purpose. Only when we have no purpose except to play will there be meaning. Work can be play, if it is doing what you want to do; that is, play and creative work may coincide. Creative play is found clearly in the work of the artist or in the search for scientific or philosophical knowledge. Almost any activity can be turned into art and Schlick wants work to become artistic; he longs for a world in which individuals engage in meaningful, joyful, playful, work. But would such an idyllic life reduce humans to an animal existence, since humans would be living for the moment rather than contemplating eternity as self-conscious beings should? Schlick says we don’t sacrifice by playing; life becomes meaningful if we do what we want to do. The result is joy, which is more than mere pleasure.

We should then be like children who are capable of joy in play (work). This passionate enthusiasm of youth, unconcerned with goals, devoted to the intrinsic nature of the play is true play. But it seem strange that youth, the preparation for adulthood, is where the meaning of life is found? Not at all says Schlick. Humans tend to think of every imperfect state as the mere prelude to another state, in the same way they often think of this life as having completion in another. But the meaning of life, if it is to be found at all, must be found in this world. Meaning may be found in youth or adulthood or old age, if one is engaged in creative play. “The more youth is realized in life, the more valuable it is, and if a person dies young, however long he may have lived, his life has had meaning.”

Summary – The meaning of life is found in joyful play, in doing what one really wants to do.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Mortiz Schlick, “On the Meaning of Life,” 71.

December 23, 2015

Summary of Terry Eagleton’s, The Meaning of Life

Terence Francis Eagleton (1943 – ) is a British literary theorist widely regarded as Britain’s most influential living literary critic. He currently serves as Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the University of Lancaster. Formerly he was Thomas Warton Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford (1992–2001) and John Edward Taylor Professor of English Literature at the University of Manchester until 2008. His 2007 book, The Meaning of Life: A Very Short Introduction, begins with this perceptive comment:

If you were to ask what provides some meaning in life nowadays for a great many people, especially men, you could do worse than reply ‘football.’ Not many of them perhaps would be willing to admit as much; but sport stands in for all those noble causes—religious faith, national sovereignty, personal honor, ethnic identity—for which, over the centuries, people have been prepared to go to their deaths. It is sport, not religion, which is now the opium of the people.

Eagleton continues by probing much deeper. He answers the question of the meaning of life without appealing to either gods or subjective meaning but to certain objective values in the natural world. He notes the false dichotomy of arguing that either there are gods that give meaning or life is meaningless:

The cosmos may not have been consciously designed, and is almost certainly not struggling to say something, but it is not just chaotic, either. On the contrary, its underlying laws reveal a beauty, symmetry, and economy that are capable of moving scientists to tears. The idea that the world is either given meaning by God, or is utterly random and absurd, is a false antithesis.

But he rejects the claims of postmodernists and constructivists who say the meaning of life is subjective—that life means whatever we say it means. “Meaning, to be sure, is something people do; but they do it in dialogue with a determinate world whose laws they did not invent, and if their meanings are to be valid, they must respect this world’s grain and texture.”

When it comes time for Eagleton to answer his question he turns to the idea of happiness as the end and purpose of human life. “The meaning of life is not a solution to a problem, but a matter of living in a certain way. It is not metaphysical, but ethical.” But how should we act in order to achieve meaning and happiness? The key is to disconnect happiness from selfishness and ally it with a love of humanity—agapeistic love is the central notion of a meaningful life. When we support each other in this manner we find the key to our own fulfillment: “For love means creating for another the space in which he might flourish, at the same time as he does this for you. The fulfillment of each becomes the ground for the fulfillment of the other. When we realize our nature in this way, we are at our best.”

In the end then happiness and love coincide. “If happiness is seen in the Aristotelian terms as the free flourishing of our faculties, and if love is the kind of reciprocity that allows this to happen, there is no final conflict between them.” Interestingly, true reciprocity is only possible among equals, so societies with great inequality are ultimately in nobody’s self-interest. Eagleton’s final metaphor compares the good and meaningful life to a jazz ensemble. The musicians improvise and do their own thing, but they also are inspired and cooperate with the other members to form a greater whole. The meaning of life consists of individuals collectively engaged in finding happiness through love and concern for each other. It turns out for Eagleton, as for Aristotle, that individual and collective well-being, happiness, and meaning are closely related.

Summary – Happiness and love are the meaning of life. We should create a world where they can thrive.

______________________________________________________________________

Eagleton, The Meaning of Life, 168.

December 22, 2015

Karl Britton on Philosophy and the Meaning of Life

Karl William Britton (1909-83) was Professor of Philosophy at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. He graduated from the University of Cambridge (Clare College) where he was President of the Union and a personal friend of Ludwig Wittgenstein. He did postgraduate work at Harvard University, and then held lectureships at Aberystwyth and Swansea before being appointed in 1951 to the chair of philosophy at King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne.

In the first chapter of his 1969 book, Philosophy and the Meaning of Life, Britton claims that the question of the meaning of life is comprised of two related and interconnected questions: 1) why does the universe exist, does it have meaning? And 2) why do I exist, what gives my life meaning? These queries lead to Britton’s first conclusion: “that for life to have a meaning it is necessary that there should be some things worth doing for their own sakes.” For some, intrinsically worthwhile values are sufficient, but others claim that this is not enough; they need goals outside of themselves set by a god or nature to make life fully meaningful. Britton suggests that the reasons people seek more than just intrinsic values and goals in life are: 1) they don’t agree on what the intrinsically valuable things are; 2) they are driven to think they were born for something; and 3) it is hard to live without believing there is some goal for their lives outside of themselves. Britton concludes that if one finds an intrinsically valuable goal in life, as well as a goal set by a god or nature, one can be said to have lived a meaningful life. The problem is whether the latter goal exists.

The first kinds of answers that Britton explores to the question of meaning are authoritative answers—particularly Western religious answers. The basic problem with such answers is that they assume problematic concepts like the existence of gods and an afterlife. He then turns to what he calls a metaphysical answer—Aristotelian contemplation. While contemplation is worthwhile, it leads to theoretical knowledge and does not fully answer the question of meaning. There are also some informal or common sense answers—meaning is to be found in service to church, country, other people, or in work, family, or self-realization. The problems here are: a) to say there is a list of meaningful things does not tell us what the list is comprised of; and b) while all of these may be necessary for a meaningful life they hardly seem sufficient; we can imagine having all of them and still wondering whether our lives are meaningful.

All of this brings Britton back to his original questions. As for his first question—w hat is the meaning, cause, or explanation of the universe—this is a theoretical question best answered by science, although people often try to answer it in non-scientific ways. The second question—what is the meaning of my life—is a practical question about how one should live and what one should value. An answer to this question must assert both facts and principles of conduct, and can be criticized because it is mistaken about either.

Britton states that for a person’s life to be meaningful it must be true that: 1) persons are guided by their convictions; 2) persons matters to themselves and others; 3) the relationships between persons matter intrinsically; and 4) persons detect a pattern in their life. Britton concludes that the possibility of these conditions being met is enough for life to be meaningful. And since it is possible for these conditions to be met then life has meaning by virtue of this possibility, whether or not that possibility is actualized.

Regarding whether there is meaning to the whole thing, Britton reminds us that this requires some teleology that is external to us. However, we could be mistaken that such teleology is real or good. In the end it is not gods or the creation of meaning that gives life meaning. Instead it is “that life has a meaning and that this arises from the possibilities which remain in the fact of all actualities. I am not merely saying that the lives of some people have meaning: I am saying that the life of any man does have meaning.”

Summary – Life has meaning because the facts of the world are such that a person’s life does matter both to themselves and to others.

_____________________________________________________________

Britton, Philosophy and the Meaning of Life, 192.