John G. Messerly's Blog, page 106

October 12, 2015

My Mom Bought Me Ice Cream

Mary Jane Hurley Messerly (1919 – 2005)

The tenth anniversary of my mom’s death has just passed. Eventually, like every one of us, she will be forgotten. But in another sense those who came before us aren’t gone; they pulsate through our being in ways unknown.

I have written about both her and my dad before, and it is difficult to add to those sentiments. But there is something about remembering, the ancestor worship of the Far East, which is valuable. Worship is too strong, but we should remember that, as Santayana put it, “We must welcome the future, remembering that soon it will be the past; and we must respect the past, remembering that it was once all that was humanly possible.” I am a futurist; I find the only hope for our species and their descendants in the future. But the future will be built upon the past as surely as it is built upon the present.

As for my mom there what I can say is that she loved me and my siblings unconditionally, showed us with her affection, and lived for her family. There are many stories to tell about her, but her is a simple one from my childhood that I remember vividly. Our near unbeatable St. Ann’s grade school soccer team had just suffered a devastating loss in the semi-finals of 6th grade division of the CYC. We lost because of bad luck—multiple shots of ours hit crossbars and goal posts—and an incredibly bad play by me as goalkeeper—on the only time the opponents got near our goal. Even a couple of my neighborhood friends came with me and mom to watch our expected victory. I was devastated. I had cost the game singlehandedly. What did my mother do? She bought me and my friends ice cream on the way home. And not just any ice cream. That rare treat of 1960s St. Louis—Velvet Freeze! No ice cream ever tasted better in my entire life.

And what better way to comfort an 11-year-old than ice cream. What she was really comforting me with was love.

October 11, 2015

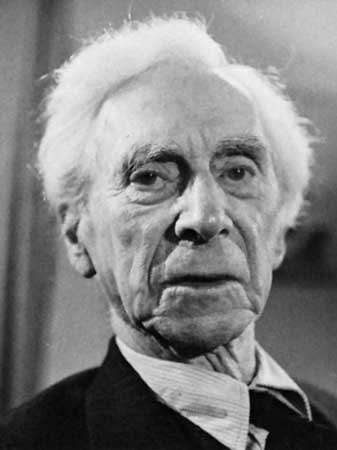

Bertrand Russell: “How To Grow Old”

Perhaps no one has spoken more clearly on growing old than the great philosopher Bertrand Russell in his essay “How To Grow Old.”

The best way to overcome it [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.

This is one of the most beautiful reflections on death I have found in all of world literature.

October 10, 2015

Bertrand Russell: His Last Written Words

The Story of the Final Manuscript

The history of Russell’s last manuscript is fascinating. This excerpt from the Independent tells the story:

Unlike most of Russell’s papers, it did not go to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, when the Russell Archives were set up in 1968. Nor did it go with the residue of Russell’s papers, now known as the ‘Second Russell Archives’, when that was sent on to McMaster after Russell’s death. Kenneth Blackwell, the Russell archivist who is generally taken by scholars in the field to be omniscient on the subject, did not even know that this manuscript existed until he saw a copy of Life of Bertrand Russell in Pictures and His Own Words , a book of photographs published to mark Russell’s centenary in 1972. One of the pictures was of Russell’s study at Plas Penrhyn, his home in north Wales. It showed his desk set out as if ready for him to begin work, with his pen, some books, some unanswered correspondence and a manuscript. This last, Blackwell noticed, was dated 1967 and … was not a manuscript he had seen before … He asked Russell’s widow about it and in 1977, a year before she died, Edith handed it over to the archives. [Yet the manuscript was not made public until 1993, on the 25th anniversary of the opening of the archives.]

, a book of photographs published to mark Russell’s centenary in 1972. One of the pictures was of Russell’s study at Plas Penrhyn, his home in north Wales. It showed his desk set out as if ready for him to begin work, with his pen, some books, some unanswered correspondence and a manuscript. This last, Blackwell noticed, was dated 1967 and … was not a manuscript he had seen before … He asked Russell’s widow about it and in 1977, a year before she died, Edith handed it over to the archives. [Yet the manuscript was not made public until 1993, on the 25th anniversary of the opening of the archives.]

The Context of the Final Manuscript

Russell had made other attempts to sum up his life and its importance, including in the famous introduction to his biography, which many consider one of the finest pieces of short prose ever written. (The famous four paragraphs can be found at the bottom of my biography.) But in his final years he became increasingly focused on the existential threat of nuclear weapons, and began to judge his life in terms of his efforts to lessen this threat. Russell was one of the most visible opponents of nuclear weapons, and along with Einstein signed what came to be known as the Russell-Einstein Manifesto condemning nuclear weapons.

Another point to remember is that at that time this short manuscript was penned Russell was 95 years old, and rumored to be senile or at least no longer capable of coherent writing. The hand-written page proved otherwise, displaying a lucidity of style that eludes most writers at their peak.

The Last Manuscript

Russell’s final words began: “The time has come to review my life as a whole, and to ask whether it has served any useful purpose or has been wholly concerned in futility. Unfortunately, no answer is possible for anyone who does not know the future.” After so many years of study, an answer to the most important question we can ask was not forthcoming. Yet a glimmer of optimism remained. The final sentences ever written by one of Western civilizations great writers and philosophers looked to the future.

Consider for a moment what our planet is and what it might be. At present, for most, there is toil and hunger, constant danger, more hatred than love. There could be a happy world, where co-operation was more in evidence than competition, and monotonous work is done by machines, where what is lovely in nature is not destroyed to make room for hideous machines whose sole business is to kill, and where to promote joy is more respected than to produce mountains of corpses. Do not say this is impossible: it is not. It waits only for men to desire it more than the infliction of torture.

There is an artist imprisoned in each one of us. Let him loose to spread joy everywhere.

Reflections – Clearly by the end of his life Russell identified with humanity at large; he wanted to escape from the limitations of his own ego. He wished for both world peace and to escape the loneliness which we all endure as necessarily isolated individuals. “Letting the artist loose” is thus a way to preserve the world and overcome our fear of individual death.

Finally here is Russell, in his late eighties, answering a question about what lessons he would leave to future generations.

October 8, 2015

Bertrand Russell’s Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech

In 1950 The Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Bertrand Russell “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” In his presentation Speech, Anders Österling, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy proclaimed:

We honour you as a brilliant champion of humanity and free thought, and it is a pleasure for us to see you here on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Nobel Foundation. With these words I request you to receive from the hands of His Majesty the King the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1950.

And at the award banquet later that evening, Robin Fåhraeus, Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, added:

Dear Professor Bertrand Russell – We salute you as one of the greatest and most influential thinkers of our age, endowed with just those four characteristics which on another occasion you have regarded to be the criteria of prominent fellow men; namely, vitality, courage, receptivity, and intelligence.

The title of Russell’s acceptance speech was “What Desires Are Politically Important?” He begins by noting that “All human activity is prompted by desire.” Of course you can resist desire from a sense of duty, but only if you desire to be dutiful, thus desire comes first and to understand people’s motives, you must know their desires. In the political sphere the primary desires are for ” … food and shelter and clothing. When these things become very scarce, there is no limit to the efforts that men will make, or to the violence that they will display, in the hope of securing them.” In addition human beings have some limitless, insatiable desires, the most important of which are —acquisitiveness, rivalry, vanity, and love of power.

Acquisitiveness is the wish to possess as much as possible, and no matter how much you acquire, you generally want more. But rivalry is an even stronger motive. We aren’t satisfied to acquire; we must have more than our rivals. We will risk our lives to ruin our competitors. Vanity also has immense power to motivate, but it too is never satisfied. The more attention we receive, the more we want because we are narcissistic. Moreover, human beings “have even committed the impiety of attributing similar desires to the Deity, whom they imagine avid for continual praise.”

But the greatest of our desires is the love of power. It is an insatiable desire and “Nothing short of omnipotence could satisfy it completely.” But most human beings want power over other people more than anything else. Still the love of power can be useful. For it motivates the pursuit of knowledge and political reformers as well as despots.

There are other secondary desires like the love of excitement and the desire to escape from boredom. Russell’s wit is ever-present. “it is … chiefly love of excitement which makes the populace applaud when war breaks out; the emotion is exactly the same as at a football match …” This love of excitement is exacerbated by the sedentary lifestyle of so many modern people. Hunter gatherers had little time for boredom, but modern people seek outlets for their love of excitement, often with disastrous results. “When crowds assemble in Trafalgar Square to cheer to the echo an announcement that the government has decided to have them killed, they would not do so if they had all walked twenty-five miles that day.” Better to use dance or music or sport as an outlet for our unused physical energy because

… so many … forms [of the desire for excitement] are destructive. It is destructive in those who cannot resist excess in alcohol or gambling. It is destructive when it takes the form of mob violence. And above all it is destructive when it leads to war. It is so deep a need that it will find harmful outlets of this kind unless innocent outlets are at hand. There are such innocent outlets at present in sport, and in politics so long as it is kept within constitutional bounds.

Other “political motives are two closely related passions to which human beings are regrettably prone: I mean fear and hate.” We normally hate what we fear, and fear what we hate. Typically we “both fear and hate whatever is unfamiliar.” We cope with fear by minimizing what’s threatening us or by adopting a Stoic temperament. But “Fear is in itself degrading; it easily becomes an obsession; it produces hate of that which is feared, and it leads headlong to excesses of cruelty.” Russell does grant that people are motivated by sympathy, adding “Perhaps the best hope for the future of mankind is that ways will be found of increasing the scope and intensity of sympathy.”

Russell summarizes by arguing that politics is about the passions of herds. “The broad instinctive mechanism upon which political edifices have to be built is one of cooperation within the herd and hostility towards other herds.” (An insight of modern biology—in group loyalty and out-group hostility.) But of course we would be better off if we were motivated by enlightened self-interest. Then

There would be no more wars, no more armies, no more navies, no more atom bombs. There would not be armies of propagandists employed in poisoning the minds of Nation A against Nation B, and reciprocally of Nation B against Nation A .. All this would happen very quickly if men desired their own happiness as ardently as they desired the misery of their neighbours.

But human beings don’t generally act in their collective self-interest, acting instead for what they consider more noble motives.

Much that passes as idealism is disguised hatred or disguised love of power. When you see large masses of men swayed by what appear to be noble motives, it is as well to look below the surface and ask yourself what it is that makes these motives effective. It is partly because it is so easy to be taken in by a facade of nobility that a psychological inquiry, such as I have been attempting, is worth making. I would say, in conclusion, that if what I have said is right, the main thing needed to make the world happy is intelligence . . .

October 7, 2015

Envy of the Future

I recently watched the following video on the online magazine of the Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies.

I would summarize the basic ideas of the video as follows. We often have negative views about the future, but perhaps that’s because we resent how good it might be. To better understand this consider going back in time and telling a grieving mother that her lifeless child will be easily saved in the future with antibiotics. She might be resentful of the future, realizing that human misery is an accident of the times we live in. Moreover a visitor from the future would pity the suffering and death we endure because of the era in which we live.

Perhaps then our apocalyptic views of the future arise because we can’t stand to think how much better the future will be, and how absurd and meaningless our current suffering will seem then. The solutions to so much of our physical and psychological suffering lie just around the corner, but we won’t be there to enjoy them. (How often I have joked in my own college classes that news of the cure for aging will arrive on my 80th birthday, but the anti-aging vaccine will only work for those less than 80 years old!) Thus we should feel pity for how difficult our lives are compared to the lives of our descendants in the future; our lives are probably poor indeed compared to the lives of those who will live in the future.

But let us not be jealous. Instead let us create a more glorious future. We may not live long enough to share in it, but we can take some comfort in the role we play in creating it. For suffering and death are not neither inevitable or noble.

October 5, 2015

Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose: What We Really Want From Our Work

The basic ideas of Daniel Pink’s Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us have entered the intellectual mainstream, but they haven’t had much impact upon the world of work. This is a shame.

have entered the intellectual mainstream, but they haven’t had much impact upon the world of work. This is a shame.

The key insight of Pink’s research is that money only motivates employees up to a certain point, beyond which it no longer works as a motivator. This does not mean that employees do best when paid low wages—everyone needs enough to live a decent human life—but it does mean that beyond a certain point people aren’t motivated by more money. After a certain point, intrinsic motivation, which comes from within yourself is much more powerful than extrinsic motivation, which comes from outside sources like money.

What people really want from work is: 1) autonomy: self-directed control over their work; 2) mastery: the chance to get better at our work; and 3) purpose: a reason to be motivated to do our work. The key is to pay people enough so that they aren’t thinking about money but thinking about work. And once you do that, the science shows that giving workers the autonomy to master and find purpose in their work will lead them to being happier and more productive. Pink illustrates these points in this clever and entertaining video:

Here are links to all of Pink’s books about work:

October 3, 2015

A Summary of Bertrand Russell’s “In Praise of Idleness”

In 1932 at age 60, my exact age as I write this post, Bertrand Russell penned a provocative essay, “In Praise of Idleness.” Russell begins,

… I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, [and] that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous …

Russell divides work into: 1) physical labor; and 2) the work of those who manage laborers, those who work allows them to buy what the laborer’s produce, politicians who try to run society, etc. In addition there are the idle rich who “are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work.” Russell despises this type of idleness, dependent as it is on the labor of others. But how did this all come to be?

For all of human history until the Industrial Revolution, an individual could produce little more than was necessary for subsistence. Originally any surplus was taken forcefully from the peasants by warriors and priests, but gradually laborers were induced believe that hard work was their duty, even though it supported the idleness of others. As a result, the laborers worked for their masters, and the masters in turn convinced themselves that what was good for them was good for all of humanity. But is this true?

Sometimes this is true; Athenian slave-owners, for instance, employed part of their leisure in making a permanent contribution to civilization which would have been impossible under a just economic system. Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

Russell saw 1930s technology was already making more leisure time possible. (This is even more true with our 21st century technology.) Yet society had not changed in the sense that it was still a place where some work long hours while others are unemployed. This is what he called “the morality of the Slave State …” He illustrates with a thought experiment,

Suppose that … a certain number of people are engaged in the manufacture of pins. They make as many pins as the world needs, working (say) eight hours a day. Someone makes an invention by which the same number of men can make twice as many pins: pins are already so cheap that hardly any more will be bought at a lower price. In a sensible world, everybody concerned in the manufacturing of pins would take to working four hours instead of eight, and everything else would go on as before. But in the actual world this would be thought demoralizing. The men still work eight hours, there are too many pins, some employers go bankrupt, and half the men previously concerned in making pins are thrown out of work. There is, in the end, just as much leisure as on the other plan, but half the men are totally idle while half are still overworked. In this way, it is insured that the unavoidable leisure shall cause misery all round instead of being a universal source of happiness. Can anything more insane be imagined?

Russell notes that the rich have always despised the idea of the poor having leisure time.

In England, in the early nineteenth century, fifteen hours was the ordinary day’s work for a man; children sometimes did as much, and very commonly did twelve hours a day. When meddlesome busybodies suggested that perhaps these hours were rather long, they were told that work kept adults from drink and children from mischief. When I was a child … certain public holidays were established by law, to the great indignation of the upper classes. I remember hearing an old Duchess say: ‘What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.’

Russell acknowledges that there is a duty to work in the sense that all human beings depend on labor for their existence. What follows from this is that we shouldn’t consume more than we produce, and we should give back to the world in labor or services for the sustenance we receive. But this is the only sense in which there is a duty to work. And while the idle rich are not virtuous, that is not “nearly so harmful as the fact that wage-earners are expected to overwork or starve.” Russell admits that some persons don’t use their leisure time wisely, but leisure time is essential for a good life. There is thus no reason why most people should be deprived of it and “only a foolish asceticism … makes us continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists.”

In the next few paragraphs Russell argues that in most societies the governing classes have always preached about the virtues of hard work. Working men are told they engage in honest labor, unpaid women told to do their saintly duty. The rich praise honest toil, the simple life, motherhood and domesticity because the ruling class wants to hoard their own political power and leisure time. But “what will happen when the point has been reached where everybody could be comfortable without working long hours?”

Russell argues that what has happens in the West is that the rich simply grab more of what is produced and amass more leisure time—many don’t even work at all. Despite the effort on the part of the rich to consume more—their yachts sit mostly unused—many things are produced that are not needed, and many people are left unemployed. When all this fails to keep enough people working “we have a war: we cause a number of people to manufacture high explosives, and a number of others to explode them … By a combination of all these devices we manage … to keep alive the notion that a great deal of severe manual work must be the lot of the average man.” It seems we are determined to be busy no matter what the cost.

The key philosophical idea for Russell when thinking about work is that physical labor, while sometimes necessary, is not the purpose of life. Why then do we so value work? First, because the rich preach that work is dignified; this keeps the workers contented. Second, because we take a certain delight in how technology transforms the world; we like to use this power. But the typical worker doesn’t think that physical or monotonous labor is meaningful. Rather “They consider work, as it should be considered, a necessary means to a livelihood, and it is from their leisure that they derive whatever happiness they may enjoy.”

Some object that people wouldn’t know what to do with more leisure time, but if this is true Russell thinks it “a condemnation of our civilization.” For why must everything be done for the sake of something else? What is wrong with deriving intrinsic pleasure from simply playing? It is tragic that we don’t value enjoyment, happiness, and pleasure as we should. Still Russell argues that leisure time isn’t best spent in frivolity; leisure time should be used intelligently. By this he doesn’t just mean highbrow intellectual activities, although he does favor active over passive activities as good uses of leisure time. He also believes that the preference of many people for passive rather than active pursuits reflects the fact that they are exhausted from too much work. Provide more time to enjoy life and people will learn to enjoy it.

Consider how some of the idle rich has spent their time. Historically, Russell says, the small leisure class has enjoyed unjust advantages, and they have been oppressive. Yet that leisure class

… contributed nearly the whole of what we call civilization. It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above. Without the leisure class, mankind would never have emerged from barbarism. The method of a leisure class without duties was, however, extraordinarily wasteful … and the class as a whole was not exceptionally intelligent. The class might produce one Darwin, but against him had to be set tens of thousands of country gentlemen who never thought of anything more intelligent than fox-hunting and punishing poachers.

Today “the universities are supposed to provide, in a more systematic way, what the leisure class provided accidentally and as a by-product.” This is better, but the university has drawbacks. For one thing those in the ivory tower are often “unaware of the preoccupations and problems of ordinary men and women.” For another thing scholars tend to write on esoteric topics in academic jargon. So academic institutions, while useful “are not adequate guardians of the interests of civilization in a world where everyone outside their walls is too busy for unutilitarian pursuits.”

Instead Russell advocates for a world where no one is compelled to work more but allowed to indulge their scientific, aesthetic, or literary tastes, or their interest in law, medicine, government, or any other interest they have. What will be the result of all this? Russell answers this question with his quintessentially beautiful prose:

Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia. The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion. Since men will not be tired in their spare time, they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid. At least one per cent will probably devote the time not spent in professional work to pursuits of some public importance, and, since they will not depend upon these pursuits for their livelihood, their originality will be unhampered, and there will be no need to conform to the standards set by elderly pundits. But it is not only in these exceptional cases that the advantages of leisure will appear. Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less persecuting and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out, partly for this reason, and partly because it will involve long and severe work for all. Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen, instead, to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever.

Reflections – The hopeful nature of this last paragraph nearly move me to tears. And these are not mere quixotic ideas . Open source code on the internet, the existence of Wikipedia, the existence of my own little blog and millions like them, all attest to the desire of people to express themselves through their labor.

Moreover, recent research shows that more money often is not want people want from work—people want autonomy, mastery and purpose in their pursuits. This is very much in line with what Russell was saying. Give people time and many will produce glorious things. So much creativity is wasted in our current social and economic system when people are forced to do what they don’t want to do, or when they are denied the minimal amount it takes to live a decent life. In my next post I will look at the surprising scientific evidence about what motivates people to work. Spoiler alert. It is not what you think.

Bertrand Russell: A Summary of “In Praise of Idleness”

In 1932 at age 60, my exact age as I write this post, Bertrand Russell penned a provocative essay, “In Praise of Idleness.” Russell begins,

… I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, [and] that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous …

Russell divides work into: 1) physical labor; and 2) the work of those who manage laborers, those who work allows them to buy what the laborer’s produce, politicians who try to run society, etc. In addition there are idle landowners who “are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work.” Russell despises the landowner’s type of idleness, dependent as it is on the labor of others. But how did this all come to be?

For all of human history until the Industrial Revolution, an individual could produce little more than was necessary for subsistence. Originally any surplus was taken forcefully from the peasants by warriors and priests, but gradually laborers were induced believe that hard work was their duty even though it supported the idleness of others. As a result, the laborers worked for their masters, and the masters in turn convinced themselves that what was good for them was good for all of humanity. But is this true?

Sometimes this is true; Athenian slave-owners, for instance, employed part of their leisure in making a permanent contribution to civilization which would have been impossible under a just economic system. Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

Russell saw 1930s technology was already making more leisure time possible. (And if that’s true imagine how much truer it is today.) Yet society had not changed; it was still a place where some work extraordinarily long hours while others are unemployed which exemplifies “the morality of the Slave State …” Here is his vivid illustration of this world.

Suppose that … a certain number of people are engaged in the manufacture of pins. They make as many pins as the world needs, working (say) eight hours a day. Someone makes an invention by which the same number of men can make twice as many pins: pins are already so cheap that hardly any more will be bought at a lower price. In a sensible world, everybody concerned in the manufacturing of pins would take to working four hours instead of eight, and everything else would go on as before. But in the actual world this would be thought demoralizing. The men still work eight hours, there are too many pins, some employers go bankrupt, and half the men previously concerned in making pins are thrown out of work. There is, in the end, just as much leisure as on the other plan, but half the men are totally idle while half are still overworked. In this way, it is insured that the unavoidable leisure shall cause misery all round instead of being a universal source of happiness. Can anything more insane be imagined?

Russell notes that the rich have always despised the idea that the poor should have leisure time.

In England, in the early nineteenth century, fifteen hours was the ordinary day’s work for a man; children sometimes did as much, and very commonly did twelve hours a day. When meddlesome busybodies suggested that perhaps these hours were rather long, they were told that work kept adults from drink and children from mischief. When I was a child … certain public holidays were established by law, to the great indignation of the upper classes. I remember hearing an old Duchess say: ‘What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.’

Russell acknowledges that there is a duty to work in the sense that all human beings depend on labor for their existence. So we shouldn’t consume more than we produce, and we should give back to the world in labor or services for the sustenance we receive. But this is the only sense in which there is a duty to work. So while being one of the idle rich is a vice, that is not “nearly so harmful as the fact that wage-earners are expected to overwork or starve.” Russell grants that some persons don’t use their leisure time wisely, but leisure time is essential for a good life. There is thus no reason why most people should be deprived of it and “only a foolish asceticism … makes us continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists.”

In the next few paragraphs Russell argues that in most societies the governing classes always preached about the virtues of hard work. Working men are told they engage in honest labor, unpaid women told to do their saintly duty. They praise honest toil, the simple life, motherhood and domesticity because the ruling class wants to hoard their political power and leisure time. But “what will happen when the point has been reached where everybody could be comfortable without working long hours?”

Russell argues that what happens in the West is that the rich simply grab more of what is produced and more leisure time—many don’t work at all. Still many things are produced that are not needed, and many are left unemployed. And when all this fails to keep enough people working “we have a war: we cause a number of people to manufacture high explosives, and a number of others to explode them … By a combination of all these devices we manage … to keep alive the notion that a great deal of severe manual work must be the lot of the average man.”

The key idea for Russell is that physical labor, while sometimes necessary, is not the purpose of life. Why then do we believe in the value of work? First, the rich preach that work is dignified as a way to keep the rest of us contented. Second, we take a certain delight in how technology transforms the world; we like to use this power. But the typical worker does not think that physical or monotonous labor is meaningful. Rather “They consider work, as it should be considered, a necessary means to a livelihood, and it is from their leisure that they derive whatever happiness they may enjoy.”

Some will still object that people wouldn’t know what to do with more leisure time, but if this is true he thinks it “a condemnation of our civilization.” For why must everything be done for the sake of something else? What is wrong with deriving intrinsic pleasure from simply playing? The result of all this we don’t value enjoyment, happiness, and pleasure as we should. But Russell argues that leisure time isn’t best spent in frivolity; leisure time should be used intelligently. By this he doesn’t just mean highbrow intellectual activities, although he does favor active over passive activities as good uses of leisure time. He also believes that the preference of many people for passive rather than active pursuits reflects the fact that they are exhausted from too much work.

Historically the small leisure class has enjoyed unjust advantages, and they have been oppressive. Still that leisure class

… contributed nearly the whole of what we call civilization. It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above. Without the leisure class, mankind would never have emerged from barbarism. The method of a leisure class without duties was, however, extraordinarily wasteful … and the class as a whole was not exceptionally intelligent. The class might produce one Darwin, but against him had to be set tens of thousands of country gentlemen who never thought of anything more intelligent than fox-hunting and punishing poachers.

Today”the universities are supposed to provide, in a more systematic way, what the leisure class provided accidentally and as a by-product.” This is better, but the university has drawbacks. For one thing those in the ivory tower are often “unaware of the preoccupations and problems of ordinary men and women.” For another thing scholars tend to write on esoteric topics in academic jargon. So academic institutions, while useful “are not adequate guardians of the interests of civilization in a world where everyone outside their walls is too busy for unutilitarian pursuits.”

Instead Russell advocates for a world where no one is compelled to work more but allowed to indulge their scientific, aesthetic, or literary tastes, or their interest in law, medicine, government, or whatever else one may be interested in. What will be the result of all this? Russell answers this question with his quintessential beautiful prose:

Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia. The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion. Since men will not be tired in their spare time, they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid. At least one per cent will probably devote the time not spent in professional work to pursuits of some public importance, and, since they will not depend upon these pursuits for their livelihood, their originality will be unhampered, and there will be no need to conform to the standards set by elderly pundits. But it is not only in these exceptional cases that the advantages of leisure will appear. Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less persecuting and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out, partly for this reason, and partly because it will involve long and severe work for all. Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen, instead, to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever.

Reflections – The hopeful nature of this last paragraph nearly move me to tears. And these are not mere quixotic ideas . Open source code on the internet, the existence of Wikipedia, the existence of my own little blog and millions like them, all attest to the desire of people to express themselves through their labor.

Recent research shows that more money often is not want people want from work—people want autonomy, mastery and purpose. This is very much in line with what Russell was saying. Give people time and many will produce glorious things. So much creativity is wasted in our current social and economic system. In my next post I will look at the surprising scientific evidence about what motivates people to work. Spoiler alert. It is not what you think.

September 30, 2015

Future Technology and Philosophy

Technology, especially intelligence augmentation and artificial intelligence, have the potential to transform the future of philosophy. Why? Because our cognitive limitations impede philosophical progress. But while we aren’t smart enough to resolve important philosophical conundrums, our cognitive limitations can be overcome by enhancing our intellectual capacities or by creating superintelligence. As a result, we would be able to better answer philosophical questions rather than being forced by intellectual honesty to remain ignorant. Put simply, if philosophy is an intellectual pursuit, then enhancing our cognitive faculties will make us better philosophers. (My colleague Phiippe Verdoux and Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom have made the same point )

As an example of accepting philosophy’s limitations consider the recent New York Times piece, “There Is No Theory of Everything,” by the philosopher Simon Critchley. (I admire his work and have written about it here and here.) Critchley admits that philosophy hasn’t made much progress “because people keep asking the same questions and [are] perplexed by the same difficulties.” But Critchley counsels us to accept that philosophy can’t give definitive answers.

Philosophy scratches at the various itches we have, not in order that we might find some cure for what ails us, but in order to scratch in the right place and begin to understand why we engage in such apparently irritating activity. Philosophy is not Neosporin. It is not some healing balm. It is an irritant, which is why Socrates described himself as a gadfly.

Next Critchley applies his insight to the question of life’s meaning. There is nothing wrong with being justifiably perplexed by our lives, he argues, but it a mistake to believe we will find an answer. Instead of seeking answers we should continue to ask questions; we should keep scratching the itch. He approvingly quotes Wittgenstein, “When you are philosophizing you have to descend into primeval chaos and feel at home there.”

But what if philosophy could be a healing balm? What if it worked better than Neosporin?What if we had the intellectual wherewithal to soothe our itch. Then we wouldn’t have to choose between accepting philosophical limitations or subscribing to imaginary supernatural cures for our existential maladies. If we augmented our intelligence we could really begin to understand what it’s all about. This ability to answer our deepest questions provides one of the very best reasons to become posthuman.

September 24, 2015

Mario Livio: The Hubble Telescope and Our Immense Universe

The Hubble Telescope has revealed an unimaginably immense and beautiful universe. In the following brief videos Dr. Mario Livio, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, discusses the philosophical implications of what we’ve seen with Hubble. This first one is called “In an Immense Universe, Small is Significant. The key idea is that even though we are extraordinarily small in this immense universe does not mean we are not significant.

The second short video Livio speaks to the beauty and power of science itself.

Livio is also the author of popular books including:

Brilliant Blunders: From Darwin to Einstein – Colossal Mistakes by Great Scientists That Changed Our Understanding of Life and the Universe ,

,

The Golden Ratio: The Story of PHI, the World’s Most Astonishing Number ,

,

, and

, and