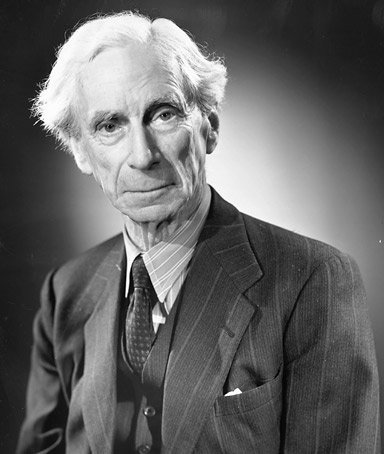

Bertrand Russell: A Summary of “In Praise of Idleness”

In 1932 at age 60, my exact age as I write this post, Bertrand Russell penned a provocative essay, “In Praise of Idleness.” Russell begins,

… I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, [and] that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous …

Russell divides work into: 1) physical labor; and 2) the work of those who manage laborers, those who work allows them to buy what the laborer’s produce, politicians who try to run society, etc. In addition there are idle landowners who “are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work.” Russell despises the landowner’s type of idleness, dependent as it is on the labor of others. But how did this all come to be?

For all of human history until the Industrial Revolution, an individual could produce little more than was necessary for subsistence. Originally any surplus was taken forcefully from the peasants by warriors and priests, but gradually laborers were induced believe that hard work was their duty even though it supported the idleness of others. As a result, the laborers worked for their masters, and the masters in turn convinced themselves that what was good for them was good for all of humanity. But is this true?

Sometimes this is true; Athenian slave-owners, for instance, employed part of their leisure in making a permanent contribution to civilization which would have been impossible under a just economic system. Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

Russell saw 1930s technology was already making more leisure time possible. (And if that’s true imagine how much truer it is today.) Yet society had not changed; it was still a place where some work extraordinarily long hours while others are unemployed which exemplifies “the morality of the Slave State …” Here is his vivid illustration of this world.

Suppose that … a certain number of people are engaged in the manufacture of pins. They make as many pins as the world needs, working (say) eight hours a day. Someone makes an invention by which the same number of men can make twice as many pins: pins are already so cheap that hardly any more will be bought at a lower price. In a sensible world, everybody concerned in the manufacturing of pins would take to working four hours instead of eight, and everything else would go on as before. But in the actual world this would be thought demoralizing. The men still work eight hours, there are too many pins, some employers go bankrupt, and half the men previously concerned in making pins are thrown out of work. There is, in the end, just as much leisure as on the other plan, but half the men are totally idle while half are still overworked. In this way, it is insured that the unavoidable leisure shall cause misery all round instead of being a universal source of happiness. Can anything more insane be imagined?

Russell notes that the rich have always despised the idea that the poor should have leisure time.

In England, in the early nineteenth century, fifteen hours was the ordinary day’s work for a man; children sometimes did as much, and very commonly did twelve hours a day. When meddlesome busybodies suggested that perhaps these hours were rather long, they were told that work kept adults from drink and children from mischief. When I was a child … certain public holidays were established by law, to the great indignation of the upper classes. I remember hearing an old Duchess say: ‘What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.’

Russell acknowledges that there is a duty to work in the sense that all human beings depend on labor for their existence. So we shouldn’t consume more than we produce, and we should give back to the world in labor or services for the sustenance we receive. But this is the only sense in which there is a duty to work. So while being one of the idle rich is a vice, that is not “nearly so harmful as the fact that wage-earners are expected to overwork or starve.” Russell grants that some persons don’t use their leisure time wisely, but leisure time is essential for a good life. There is thus no reason why most people should be deprived of it and “only a foolish asceticism … makes us continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists.”

In the next few paragraphs Russell argues that in most societies the governing classes always preached about the virtues of hard work. Working men are told they engage in honest labor, unpaid women told to do their saintly duty. They praise honest toil, the simple life, motherhood and domesticity because the ruling class wants to hoard their political power and leisure time. But “what will happen when the point has been reached where everybody could be comfortable without working long hours?”

Russell argues that what happens in the West is that the rich simply grab more of what is produced and more leisure time—many don’t work at all. Still many things are produced that are not needed, and many are left unemployed. And when all this fails to keep enough people working “we have a war: we cause a number of people to manufacture high explosives, and a number of others to explode them … By a combination of all these devices we manage … to keep alive the notion that a great deal of severe manual work must be the lot of the average man.”

The key idea for Russell is that physical labor, while sometimes necessary, is not the purpose of life. Why then do we believe in the value of work? First, the rich preach that work is dignified as a way to keep the rest of us contented. Second, we take a certain delight in how technology transforms the world; we like to use this power. But the typical worker does not think that physical or monotonous labor is meaningful. Rather “They consider work, as it should be considered, a necessary means to a livelihood, and it is from their leisure that they derive whatever happiness they may enjoy.”

Some will still object that people wouldn’t know what to do with more leisure time, but if this is true he thinks it “a condemnation of our civilization.” For why must everything be done for the sake of something else? What is wrong with deriving intrinsic pleasure from simply playing? The result of all this we don’t value enjoyment, happiness, and pleasure as we should. But Russell argues that leisure time isn’t best spent in frivolity; leisure time should be used intelligently. By this he doesn’t just mean highbrow intellectual activities, although he does favor active over passive activities as good uses of leisure time. He also believes that the preference of many people for passive rather than active pursuits reflects the fact that they are exhausted from too much work.

Historically the small leisure class has enjoyed unjust advantages, and they have been oppressive. Still that leisure class

… contributed nearly the whole of what we call civilization. It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above. Without the leisure class, mankind would never have emerged from barbarism. The method of a leisure class without duties was, however, extraordinarily wasteful … and the class as a whole was not exceptionally intelligent. The class might produce one Darwin, but against him had to be set tens of thousands of country gentlemen who never thought of anything more intelligent than fox-hunting and punishing poachers.

Today”the universities are supposed to provide, in a more systematic way, what the leisure class provided accidentally and as a by-product.” This is better, but the university has drawbacks. For one thing those in the ivory tower are often “unaware of the preoccupations and problems of ordinary men and women.” For another thing scholars tend to write on esoteric topics in academic jargon. So academic institutions, while useful “are not adequate guardians of the interests of civilization in a world where everyone outside their walls is too busy for unutilitarian pursuits.”

Instead Russell advocates for a world where no one is compelled to work more but allowed to indulge their scientific, aesthetic, or literary tastes, or their interest in law, medicine, government, or whatever else one may be interested in. What will be the result of all this? Russell answers this question with his quintessential beautiful prose:

Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia. The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion. Since men will not be tired in their spare time, they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid. At least one per cent will probably devote the time not spent in professional work to pursuits of some public importance, and, since they will not depend upon these pursuits for their livelihood, their originality will be unhampered, and there will be no need to conform to the standards set by elderly pundits. But it is not only in these exceptional cases that the advantages of leisure will appear. Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less persecuting and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out, partly for this reason, and partly because it will involve long and severe work for all. Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen, instead, to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever.

Reflections – The hopeful nature of this last paragraph nearly move me to tears. And these are not mere quixotic ideas . Open source code on the internet, the existence of Wikipedia, the existence of my own little blog and millions like them, all attest to the desire of people to express themselves through their labor.

Recent research shows that more money often is not want people want from work—people want autonomy, mastery and purpose. This is very much in line with what Russell was saying. Give people time and many will produce glorious things. So much creativity is wasted in our current social and economic system. In my next post I will look at the surprising scientific evidence about what motivates people to work. Spoiler alert. It is not what you think.