David Boyle's Blog, page 81

May 17, 2013

Google: is there anybody in there?

The day the hapless Google head of northern Europe was battered by Margaret Hodge for their "devious and unethical" approach to paying tax in the UK - or not doing so, in this case - my Google blog (which you are now reading) ran into trouble.

The day the hapless Google head of northern Europe was battered by Margaret Hodge for their "devious and unethical" approach to paying tax in the UK - or not doing so, in this case - my Google blog (which you are now reading) ran into trouble.Thousands of hits are being recorded by their counting machine from the Far East, routed via a porn site called 'topblogstories'. The same thing is happening via a slimming website in the USA. Much as I would like it to, my blog has never generated hits in the thousands per day bracket before, and - since these hits are not showing up under any of the posts - something has gone wrong. It doesn't really affect the blog, but it is disturbing.

But how do you ask Google's advice, still less ask them to do something about it?

Needless to say, this particular problem does not appear on their rather short list of online problems. No UK telephone number is shown. There is no email address for customer service. There is a website with a phone number in the USA, but there are voluminous messages of disgust from people underneath because the calls are never answered.

There is a UK office number, but if you don't have an extension number, there is nobody to speak to. I tried dialling 0 and was just held on the line ringing out hopelessly and pointlessly for half an hour before I gave up.

There is a feedback button which allows you to send a message about problems, but the response says they don't guarantee to reply to everyone. That's an understatement - I've sent ten messages so far and no response.

Now, I'm a good Google customer. I use their email system and their blog system and I even earn a tiny amount of money from adverts on the site. But Google apparently has such contempt for me that they fear any kind of contact.

I'm forced to ask the question - is there anybody there? At the heart of this global beast, is there anything at all - any human being, any heartbeat, any interest at all in their customers? Or is it just an empty echoing, soulless shell of conceit and arrogance?

The great Anita Roddick used to say that global corporations were like dinosaurs, unable to feel any emotion except greed and fear. Is this Google now?

No doubt they would say that this is just the future of business, as their de-humanised machines strip us all of our information and sell it back to us. This is the new virtual world. Not a bit of it. This is the result of monopoly. It is because they have no competition, and the competition authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have been asleep on the job.

When the three American giants were first castigated over here for their tax avoidance schemes, the two monopolies ignored the fuss completely. It was only Starbucks, which has competitors, which reacted. The truth is that when competition authorities snooze and allow companies like Google to build up a monopoly position, then the customers are more than taken for granted - they are completely ignored.

So once I sort this out, I'm finding a better way of organising my blog and my emails. It may take a bit of time - certainly longer than it would if there was a proper UK competitor for Google, even a small one - but I will do it.

And of course, I'm writing this diatribe on a blog hosted by Google, the great absentees. Will they censor it? Of course they won't - because there is nobody there to read it.

Published on May 17, 2013 00:55

May 16, 2013

Government responds to the Boyle Review

This time last year, I was preparing to start work on the government's independent review into barriers to choice in public services. My pencils were sharpened, my only suit pressed, my plans not quite formulated.

I eventually reported to the Cabinet Office and Treasury in January, and the result has become known - rather embarrassingly, but this is the way they do things in government - as the Boyle Review. It received an unexpectedly enthusiastic response from the Cabinet Office ministers, and from Danny Alexander at the Treasury who had been so involved in commissioning me. I went away relatively confident that the government broadly agreed with my approach and proposals.

Before I go on, let me just say what that approach was. The core of the review was to get out there and talk to the users of services, and find out about their experience of 'choice' - and check what I heard with a major poll - and reach some conclusions:

First, that the bureaucratic barriers to choice remain powerful if you are less confident or articulate; and if you want something slightly out of the mainstream then there is inequality present in the scope of choice available to everyday people across the UK.Second, people, especially the disadvantaged, need information and advice on what choices are available to them, yet often this proves problematic. Some people do not easily have access to the internet and this makes it even harder to find out what choices are available, and they also want face to face advice to make sense of it; Finally, the kinds of choices people think they are getting are often not what they are being offered in reality, and there is a need for more flexibility in the way services are delivered.The last one was really key to it. Competition has a place in public services - there is no reason why people should put up with poor services - and so does online information. But choice needs to be so much more than that, if it is going to provide people with the services they want - it needs to provide a series of levers that allow for service flexibility.

I called that 'broad choice' to distinguish it from the narrow, formal choice that the system has been struggling to provide so far.

So I'm pleased that the government's 'initial response', published today, is so positive. I'm glad they use words like 'enlightening'. I'm pleased they have supported seven out of ten of my recommendations - though this slightly obscures the full truth, which is that some of these were happening anyway and some have been agreed by especially careful wording and are not really quite what I meant, as they must know. Such is the world of government, and I understand that.

I am pleased that they agree with my proposal about publishing information comparing the performance of schools achieving the best outcomes for free school meal children.

I'm glad they have accepted the 'co-production' recommendations about social care assessments, which are now in the Care Bill - more on that another time.

I'm particularly glad that they have agreed that there will be an advisor to the Prime Minister who will "champion broad choice across public services and work across departments and services to tackle barriers to choice."

I take this to mean that they accept my basic premise that choice needs to be broadened out if it is going to be (a) meaningful and (b) effective. It rather depends on who they appoint, of course. I know who I want them to appoint (and I'm not going to ruin their chances by naming them here).

Where I am disappointed, it is because the whole thrust of the review, and so many of the conversations I had with service users - not to mention the poll findings by Ipsos-MORI - suggest that, for a good third of people using services, online information simply isn't enough. So, although online information is important, face to face contact is absolutely vital if everyone is to get the kind of choices they need.

I proposed a way forward which evidence suggests would also save money: extending the growing role of peer support volunteers into giving signposting and choice advice. This is what they say:

"We will explore how to take this recommendation forward including expanding existing programmes; improving awareness of peer support programmes and looking at how we work with mentors and volunteers."

That isn't a no, but it isn't quite a yes, yet. I am assured that they are looking at the best model for taking this forward, so we shall see. But this is a vital reform, merging the co-production and the choice agenda, which would do more than anything else to bring choice - broad or narrow - to the whole population.

I won't be the only one to detect a defensive note in the response. This reveals, perhaps, how nervous some departments were when the review began. But there is no need to be defensive. The government was brave enough to commission me to see what was really happening on the ground - people's real experience of choice.

The difficulties I found won't be solved overnight, and everyone understands that. But my impression is that the narrow choice agenda, which requires a huge infrastructure of watchdogs and competition institutions, may have got as far as it is going to for a while.

I believe in choice, and choice beyond simply encouraging competition - not just because it is good for service users, but because flexibility is good for public services too. Sclerosis is expensive.

Whether my review will turn out to have found a way to revitalise the choice idea depends on what happens next. Watch this space...

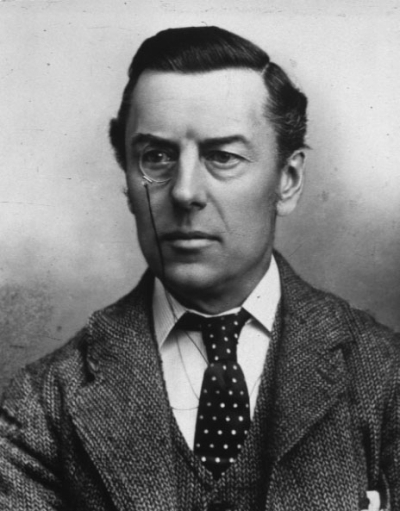

More on my review (please ignore terrible picture of me) in Civil Service World interview. See also coverage back in January.

I eventually reported to the Cabinet Office and Treasury in January, and the result has become known - rather embarrassingly, but this is the way they do things in government - as the Boyle Review. It received an unexpectedly enthusiastic response from the Cabinet Office ministers, and from Danny Alexander at the Treasury who had been so involved in commissioning me. I went away relatively confident that the government broadly agreed with my approach and proposals.

Before I go on, let me just say what that approach was. The core of the review was to get out there and talk to the users of services, and find out about their experience of 'choice' - and check what I heard with a major poll - and reach some conclusions:

First, that the bureaucratic barriers to choice remain powerful if you are less confident or articulate; and if you want something slightly out of the mainstream then there is inequality present in the scope of choice available to everyday people across the UK.Second, people, especially the disadvantaged, need information and advice on what choices are available to them, yet often this proves problematic. Some people do not easily have access to the internet and this makes it even harder to find out what choices are available, and they also want face to face advice to make sense of it; Finally, the kinds of choices people think they are getting are often not what they are being offered in reality, and there is a need for more flexibility in the way services are delivered.The last one was really key to it. Competition has a place in public services - there is no reason why people should put up with poor services - and so does online information. But choice needs to be so much more than that, if it is going to provide people with the services they want - it needs to provide a series of levers that allow for service flexibility.

I called that 'broad choice' to distinguish it from the narrow, formal choice that the system has been struggling to provide so far.

So I'm pleased that the government's 'initial response', published today, is so positive. I'm glad they use words like 'enlightening'. I'm pleased they have supported seven out of ten of my recommendations - though this slightly obscures the full truth, which is that some of these were happening anyway and some have been agreed by especially careful wording and are not really quite what I meant, as they must know. Such is the world of government, and I understand that.

I am pleased that they agree with my proposal about publishing information comparing the performance of schools achieving the best outcomes for free school meal children.

I'm glad they have accepted the 'co-production' recommendations about social care assessments, which are now in the Care Bill - more on that another time.

I'm particularly glad that they have agreed that there will be an advisor to the Prime Minister who will "champion broad choice across public services and work across departments and services to tackle barriers to choice."

I take this to mean that they accept my basic premise that choice needs to be broadened out if it is going to be (a) meaningful and (b) effective. It rather depends on who they appoint, of course. I know who I want them to appoint (and I'm not going to ruin their chances by naming them here).

Where I am disappointed, it is because the whole thrust of the review, and so many of the conversations I had with service users - not to mention the poll findings by Ipsos-MORI - suggest that, for a good third of people using services, online information simply isn't enough. So, although online information is important, face to face contact is absolutely vital if everyone is to get the kind of choices they need.

I proposed a way forward which evidence suggests would also save money: extending the growing role of peer support volunteers into giving signposting and choice advice. This is what they say:

"We will explore how to take this recommendation forward including expanding existing programmes; improving awareness of peer support programmes and looking at how we work with mentors and volunteers."

That isn't a no, but it isn't quite a yes, yet. I am assured that they are looking at the best model for taking this forward, so we shall see. But this is a vital reform, merging the co-production and the choice agenda, which would do more than anything else to bring choice - broad or narrow - to the whole population.

I won't be the only one to detect a defensive note in the response. This reveals, perhaps, how nervous some departments were when the review began. But there is no need to be defensive. The government was brave enough to commission me to see what was really happening on the ground - people's real experience of choice.

The difficulties I found won't be solved overnight, and everyone understands that. But my impression is that the narrow choice agenda, which requires a huge infrastructure of watchdogs and competition institutions, may have got as far as it is going to for a while.

I believe in choice, and choice beyond simply encouraging competition - not just because it is good for service users, but because flexibility is good for public services too. Sclerosis is expensive.

Whether my review will turn out to have found a way to revitalise the choice idea depends on what happens next. Watch this space...

More on my review (please ignore terrible picture of me) in Civil Service World interview. See also coverage back in January.

Published on May 16, 2013 04:52

May 15, 2013

The great paradox: concentrating on cutting costs drives them up

Down in the forest, something stirs. Shhh now, don't scare it away. Something is emerging from Labour's policy review, at least according to John Harris in the Guardian. It seems to include a combination of three approaches - or is it four, I can't quite grasp which. And they are as follows:

1. Balancing the budget over a decade, involving an approach to austerity that Harris quotes insiders as calling 'brutal'.

2. Growth led by house-building.

3. Re-thinking how the public sector fits together, with an emphasis on prevention - which is a success for my colleagues at the New Economics Foundation who are among those pedalling exactly this.

4. Turbo-charged localism.

My first thought about this, apart from the fact that it will divide the Labour Party, is that it appears to be an attempt to borrow the coalition's rhetoric and make it work rather better. Perhaps even along the lines the Lib Dems might attempt if they had a free hand. Hence the controversy.

My second thought is that turbo-charged localism is not, never has been, and probably never will be, something the party of Beatrice and Sidney Webb will be able to carry out in practice. But, hey, perhaps I will be surprised.

But what really interests me is how balancing the budget and reorganising the public sector might fit together - and could still be made to fit together by the coalition. Because to genuinely reduce the cost of public services, you really need a big idea about how they might work differently - you need a diagnosis and a prescription.

The coalition has a diagnosis - they understood the disastrous effect of targets - but no prescription that really fits it. New Labour had a prescription but a faulty diagnosis.

Without the diagnosis, public service reform just becomes public service cuts, and they often lock in costs elsewhere in the system. I have written before about how historians covering these years will regard our main story as the looming crisis in public services, and the race against time by empowered service professionals to come up with the ideas they need to re-configure them.

But it is worse than that. Without a big idea behind spending cuts, any government gets impaled on the horns of a dilemma described so powerfully by the systems thinker John Seddon:

"The truth is counterintuitive: focusing on costs drives costs up. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to work out that we'd be better off if we could design a service that meets people's needs, quickly, effectively and once."

There is the great paradox which has eluded successive governments. If you focus on cutting costs, the costs will rise. If you try and provide a more effective service - which might well not be digital by default - then costs will fall.

Seddon is an important figure in all this. He is the presiding genius over a whole range of related ideas that, taken together, would completely transform the effectiveness of our services. Before the election, I took him to see Vince Cable, hoping they would hit it off (they didn't really get the chance). After the election, I organised a debate at the Royal Society of Arts with him under the title 'The New Efficiency'.

He remains a kind of king-over-the-water for the kind of service manager who is most frustrated by the direction of public service reform over the past decade.

Seddon's frustration with Whitehall is expressed in a wonderful monthly e-newsletter which has become required reading in local government circles because it is so enjoyably rude.

He isn't right about absolutely everything - this isn't a hagiographical blog - but I have come to believe that he represents the wave that is about to break over public services.

Perhaps Labour will run with this approach, and the related approaches I describe. Perhaps they won't. Perhaps the coalition will realise, at this late stage, what needs to happen. I don't know. But the wave will eventually break, sweeping the whole caboodle of lesser ideas - Lean, digital by default, payment-by-results - into history.

1. Balancing the budget over a decade, involving an approach to austerity that Harris quotes insiders as calling 'brutal'.

2. Growth led by house-building.

3. Re-thinking how the public sector fits together, with an emphasis on prevention - which is a success for my colleagues at the New Economics Foundation who are among those pedalling exactly this.

4. Turbo-charged localism.

My first thought about this, apart from the fact that it will divide the Labour Party, is that it appears to be an attempt to borrow the coalition's rhetoric and make it work rather better. Perhaps even along the lines the Lib Dems might attempt if they had a free hand. Hence the controversy.

My second thought is that turbo-charged localism is not, never has been, and probably never will be, something the party of Beatrice and Sidney Webb will be able to carry out in practice. But, hey, perhaps I will be surprised.

But what really interests me is how balancing the budget and reorganising the public sector might fit together - and could still be made to fit together by the coalition. Because to genuinely reduce the cost of public services, you really need a big idea about how they might work differently - you need a diagnosis and a prescription.

The coalition has a diagnosis - they understood the disastrous effect of targets - but no prescription that really fits it. New Labour had a prescription but a faulty diagnosis.

Without the diagnosis, public service reform just becomes public service cuts, and they often lock in costs elsewhere in the system. I have written before about how historians covering these years will regard our main story as the looming crisis in public services, and the race against time by empowered service professionals to come up with the ideas they need to re-configure them.

But it is worse than that. Without a big idea behind spending cuts, any government gets impaled on the horns of a dilemma described so powerfully by the systems thinker John Seddon:

"The truth is counterintuitive: focusing on costs drives costs up. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to work out that we'd be better off if we could design a service that meets people's needs, quickly, effectively and once."

There is the great paradox which has eluded successive governments. If you focus on cutting costs, the costs will rise. If you try and provide a more effective service - which might well not be digital by default - then costs will fall.

Seddon is an important figure in all this. He is the presiding genius over a whole range of related ideas that, taken together, would completely transform the effectiveness of our services. Before the election, I took him to see Vince Cable, hoping they would hit it off (they didn't really get the chance). After the election, I organised a debate at the Royal Society of Arts with him under the title 'The New Efficiency'.

He remains a kind of king-over-the-water for the kind of service manager who is most frustrated by the direction of public service reform over the past decade.

Seddon's frustration with Whitehall is expressed in a wonderful monthly e-newsletter which has become required reading in local government circles because it is so enjoyably rude.

He isn't right about absolutely everything - this isn't a hagiographical blog - but I have come to believe that he represents the wave that is about to break over public services.

Perhaps Labour will run with this approach, and the related approaches I describe. Perhaps they won't. Perhaps the coalition will realise, at this late stage, what needs to happen. I don't know. But the wave will eventually break, sweeping the whole caboodle of lesser ideas - Lean, digital by default, payment-by-results - into history.

Published on May 15, 2013 04:10

May 14, 2013

To save Europe, the euro has to go

As a blogger, I would like to claim that I am immensely prescient. The truth is usually otherwise, unfortunately. But there is one exception, which I can't help mentioning. This is what I said in my first Lib Dem conference speech in 2001 (actually, it was my second, but we draw a veil over the first):

"There is a fundamental problem at the heart of the euro that makes me fear for the future of Europe. And it’s this: single currencies tend to favour the rich and impoverish the poor.

They do so because changing the value of your currency, and varying your interest rate, is the way that disadvantaged places are able to make their goods more affordable. When you prevent them from doing that, you trap whole cities and regions – the poorest people in the poorest places – without being able to trade their way out...

That’s the danger of the euro as presently arranged, and don’t underestimate it. It means success for the cities that are already successful. It means a real struggle for the great Lib Dem cities of Liverpool and Sheffield. It means a potent recruiting ground for the next generation of fascists in the regions that no longer count."

I can't say I convinced the hall or won the day, and there are obvious elements which date this - Lib Dem Liverpool, for example, and the fact that I was talking about Britain in the euro, which never happened, thank goodness. But I was right, and the plight of Greece and other countries in southern Europe make it all too clear.

Apart from celebrating a rare moment when I called it correctly, my reason for writing about this now is that UKIP and an imploding Conservative Party are not the only reasons why the European Union is a key political issue. The truth is that Europe is facing its own crisis, and that crisis stems largely, but not entirely ,from the euro.

It was, and is, a Napoleonic project, dangerously centralising, naive in its economics and potentially terrifying in its effects - as the rise of the Far Right and other weird peculiarities suggest. It transforms the EU into a colonial project, demanding abject agreement from economies that cannot work with an interest rate set to suit the German economy. It is bound to fail and, until it does, it threatens to bring down the European Union with it.

I have often wondered whether it was historically inevitable that the UK would eventually leave. We always find ourselves resisting Napoleonic projects. We always resist ultramontanist ones too and any other centralising directives from Rome - or Brussels, as we call it these days. We follow the Reformation path and it may be inevitable that will repeat Henry VIII's secession.

I am not in favour of the European Union because I believe in the central control of the continent. Or even because it is a de-regulated trading bloc - though it is this aspect of EU rules that the UKIP tendency usually objects to (and even leaving the EU wouldn't rid them of regulations governing electrical goods or the shape of vegetables).

I am in favour of the Union because it has kept the peace of Europe for two unprecedented generations. A European war is unthinkable now, but it wouldn't be unthinkable without European institutions that can settle disputes.

That is the moral case, the Liberal case, for Europe - and the celebrations in August 2014 are an opportunity for putting the case again.

But we can't assume that the European Union can be a Liberal institution, because that is now in doubt. These issues are tough ones for Liberals, because I don't believe the Union can survive as the policeman of a single currency.

The euro might survive, but not in its current form as the only currency for most of the continent. We don't have to go back to national currencies, though regional ones would be useful - and may emerge by default from the struggling cities of southern Europe.

Either way, the sooner the great straitjacket can be loosened and the Napoleonic yoke lifted again, the better for all of us. Then maybe the Union can survive. But not otherwise, and - if it doesn't happen soon - the UK will have left it, and that would be tragic for both sides.

"There is a fundamental problem at the heart of the euro that makes me fear for the future of Europe. And it’s this: single currencies tend to favour the rich and impoverish the poor.

They do so because changing the value of your currency, and varying your interest rate, is the way that disadvantaged places are able to make their goods more affordable. When you prevent them from doing that, you trap whole cities and regions – the poorest people in the poorest places – without being able to trade their way out...

That’s the danger of the euro as presently arranged, and don’t underestimate it. It means success for the cities that are already successful. It means a real struggle for the great Lib Dem cities of Liverpool and Sheffield. It means a potent recruiting ground for the next generation of fascists in the regions that no longer count."

I can't say I convinced the hall or won the day, and there are obvious elements which date this - Lib Dem Liverpool, for example, and the fact that I was talking about Britain in the euro, which never happened, thank goodness. But I was right, and the plight of Greece and other countries in southern Europe make it all too clear.

Apart from celebrating a rare moment when I called it correctly, my reason for writing about this now is that UKIP and an imploding Conservative Party are not the only reasons why the European Union is a key political issue. The truth is that Europe is facing its own crisis, and that crisis stems largely, but not entirely ,from the euro.

It was, and is, a Napoleonic project, dangerously centralising, naive in its economics and potentially terrifying in its effects - as the rise of the Far Right and other weird peculiarities suggest. It transforms the EU into a colonial project, demanding abject agreement from economies that cannot work with an interest rate set to suit the German economy. It is bound to fail and, until it does, it threatens to bring down the European Union with it.

I have often wondered whether it was historically inevitable that the UK would eventually leave. We always find ourselves resisting Napoleonic projects. We always resist ultramontanist ones too and any other centralising directives from Rome - or Brussels, as we call it these days. We follow the Reformation path and it may be inevitable that will repeat Henry VIII's secession.

I am not in favour of the European Union because I believe in the central control of the continent. Or even because it is a de-regulated trading bloc - though it is this aspect of EU rules that the UKIP tendency usually objects to (and even leaving the EU wouldn't rid them of regulations governing electrical goods or the shape of vegetables).

I am in favour of the Union because it has kept the peace of Europe for two unprecedented generations. A European war is unthinkable now, but it wouldn't be unthinkable without European institutions that can settle disputes.

That is the moral case, the Liberal case, for Europe - and the celebrations in August 2014 are an opportunity for putting the case again.

But we can't assume that the European Union can be a Liberal institution, because that is now in doubt. These issues are tough ones for Liberals, because I don't believe the Union can survive as the policeman of a single currency.

The euro might survive, but not in its current form as the only currency for most of the continent. We don't have to go back to national currencies, though regional ones would be useful - and may emerge by default from the struggling cities of southern Europe.

Either way, the sooner the great straitjacket can be loosened and the Napoleonic yoke lifted again, the better for all of us. Then maybe the Union can survive. But not otherwise, and - if it doesn't happen soon - the UK will have left it, and that would be tragic for both sides.

Published on May 14, 2013 01:18

May 13, 2013

How privatisation ran out of steam

The word ‘privatisation’ has a chequered history. It was actually coined as ‘reprivatisation’ by the Nazi Party in the 1930s, as a way of handing over government functions to loyal party officials. The phrase was then borrowed by the great management writer Peter Drucker in 1969, proposing that governments use the talent in other sectors to deliver some of their objectives. “Government is a poor manager …. It has no choice but to be bureaucratic,” he wrote.

That was the basic idea that was taken up by Conservative thinkers in the 1970s. Sir Keith Joseph’s Centre for Policy Studies produced a pamphlet in 1975 which set out the case: “There is now abundant evidence that state enterprises in the UK have not served well either their customers, or their employees, or the taxpayer, for when the state owns, nobody owns and when nobody owns, nobody cares.”

It was a powerful proposition. But it wasn't until their second term that Margaret Thatcher's ministers grasped the sheer power of the privatisation idea. It was obvious to anyone who tried to use them that the nation’s telephone boxes were largely out of order, and so the privatisation of British Telecom in 1984 was a popular move. As many as 2.3m people brought shares.

It was a powerful proposition. But it wasn't until their second term that Margaret Thatcher's ministers grasped the sheer power of the privatisation idea. It was obvious to anyone who tried to use them that the nation’s telephone boxes were largely out of order, and so the privatisation of British Telecom in 1984 was a popular move. As many as 2.3m people brought shares.

Three years later, the Treasury had earned £24 billion from privatisation, and the sale of British Gas provided four per cent of public spending for 1986/7. The idea of privatising state industries had spread to France and the USA and Canada. Even Cuba and China were testing it out.

The merchant bank Rothschilds had set up a special unit to organise privatisations, under the future Conservative frontbencher John Redwood, and Conservative theorists were muttering darkly about selling off the Atomic Energy Authority and the BBC. In fact, selling nuclear power stations was the thin end of the wedge. No amount of spin could disguise the fact that they weren’t economic.

The original impetus to sell BT was partly to find private investment for telecoms and partly because of Drucker’s original idea that private companies were more efficient.

Privatising public services would break those bureaucratic straitjackets, and get a new entrepreneurial energy about the place. They would focus on customers. Things would happen. There would be enterprise and imagination. The human element would weave its magic.

But it didn’t happen. The early privatisations led to dramatic increases in effectiveness but, after that, things slowed down. Private corporate giants turned out to be as inflexible and hopelessly unproductive (at least as far as the customers were concerned) as the public corporate giants: they just provided considerably fewer jobs.

Often the costs remained much the same. Most privatised services are as sclerotic, inhuman and monstrous as their predecessors were.

By the time New Labour was privatising, and experimenting disastrously with PFI contracts that locked in costs for a generation, the supposedly efficient private utilities are largely in the grip of the same illusions about efficiency as the public sector, with phalanxes of call centres, targets and standards, and had become as inflexible as any nationalised industry.

“We are committed to a market economy at the national level, and a non-market, centrally planned, hierarchically managed economy within most corporations,” wrote the Observer columnist Simon Caulkin at the time.

So Peter Drucker was wrong. As it turned out, big companies and big contracts tend to become bureaucratic too. The point wasn’t that private was better than public, it was that small was better than big, because small allowed for the human element. Ownership wasn’t important, at least in its strict sense.

Even so, it was Drucker who provided the clue. Anyone can be an entrepreneur if the organisation is structured to encourage them:

“The most entrepreneurial, innovative people behave like the worst time-serving bureaucrat or power-hungry politician six months after they have taken over the management of a public service institution.”

And so it proved.

So if privatisation isn't the answer - and most sane people regard it as a recipe for sclerosis and corroding standards for the Post Office - what is? How do you provide the kind of flexibility and human-scale imagination to make organisations work? It certainly isn't the profit motive - nobody who phones a BT call centre these days could believe that. It isn't public ownership either, at least not by itself.

I tried to answer the question in my book The Human Element. Mutualism certainly provides a clue, but is probably not enough by itself either.

I got another clue from the chief executive of a major health social enterprise I met while I was carrying out the independent review for the Cabinet Office. He told me he was delivering health and social care services across a wide population, but still on a small scale compared to working in the public sector.

He also told me he had felt he had to leave direct employment by the NHS in order to re-discover the values of the NHS. Of course, he is still delivering NHS services and in a highly flexible and responsive way - but he has the room for manoeuvre to use his imagination and the imagination of his other staff, and of course the imagination of the people he is delivering services to.

This seems to me what Karl Popper meant when he talked about “setting free the critical powers of man”. The very heart of modern Liberalism.

Will Post Office privatisation set free the critical powers of the people who work there? Believe that and you will believe just about anything.

That was the basic idea that was taken up by Conservative thinkers in the 1970s. Sir Keith Joseph’s Centre for Policy Studies produced a pamphlet in 1975 which set out the case: “There is now abundant evidence that state enterprises in the UK have not served well either their customers, or their employees, or the taxpayer, for when the state owns, nobody owns and when nobody owns, nobody cares.”

It was a powerful proposition. But it wasn't until their second term that Margaret Thatcher's ministers grasped the sheer power of the privatisation idea. It was obvious to anyone who tried to use them that the nation’s telephone boxes were largely out of order, and so the privatisation of British Telecom in 1984 was a popular move. As many as 2.3m people brought shares.

It was a powerful proposition. But it wasn't until their second term that Margaret Thatcher's ministers grasped the sheer power of the privatisation idea. It was obvious to anyone who tried to use them that the nation’s telephone boxes were largely out of order, and so the privatisation of British Telecom in 1984 was a popular move. As many as 2.3m people brought shares. Three years later, the Treasury had earned £24 billion from privatisation, and the sale of British Gas provided four per cent of public spending for 1986/7. The idea of privatising state industries had spread to France and the USA and Canada. Even Cuba and China were testing it out.

The merchant bank Rothschilds had set up a special unit to organise privatisations, under the future Conservative frontbencher John Redwood, and Conservative theorists were muttering darkly about selling off the Atomic Energy Authority and the BBC. In fact, selling nuclear power stations was the thin end of the wedge. No amount of spin could disguise the fact that they weren’t economic.

The original impetus to sell BT was partly to find private investment for telecoms and partly because of Drucker’s original idea that private companies were more efficient.

Privatising public services would break those bureaucratic straitjackets, and get a new entrepreneurial energy about the place. They would focus on customers. Things would happen. There would be enterprise and imagination. The human element would weave its magic.

But it didn’t happen. The early privatisations led to dramatic increases in effectiveness but, after that, things slowed down. Private corporate giants turned out to be as inflexible and hopelessly unproductive (at least as far as the customers were concerned) as the public corporate giants: they just provided considerably fewer jobs.

Often the costs remained much the same. Most privatised services are as sclerotic, inhuman and monstrous as their predecessors were.

By the time New Labour was privatising, and experimenting disastrously with PFI contracts that locked in costs for a generation, the supposedly efficient private utilities are largely in the grip of the same illusions about efficiency as the public sector, with phalanxes of call centres, targets and standards, and had become as inflexible as any nationalised industry.

“We are committed to a market economy at the national level, and a non-market, centrally planned, hierarchically managed economy within most corporations,” wrote the Observer columnist Simon Caulkin at the time.

So Peter Drucker was wrong. As it turned out, big companies and big contracts tend to become bureaucratic too. The point wasn’t that private was better than public, it was that small was better than big, because small allowed for the human element. Ownership wasn’t important, at least in its strict sense.

Even so, it was Drucker who provided the clue. Anyone can be an entrepreneur if the organisation is structured to encourage them:

“The most entrepreneurial, innovative people behave like the worst time-serving bureaucrat or power-hungry politician six months after they have taken over the management of a public service institution.”

And so it proved.

So if privatisation isn't the answer - and most sane people regard it as a recipe for sclerosis and corroding standards for the Post Office - what is? How do you provide the kind of flexibility and human-scale imagination to make organisations work? It certainly isn't the profit motive - nobody who phones a BT call centre these days could believe that. It isn't public ownership either, at least not by itself.

I tried to answer the question in my book The Human Element. Mutualism certainly provides a clue, but is probably not enough by itself either.

I got another clue from the chief executive of a major health social enterprise I met while I was carrying out the independent review for the Cabinet Office. He told me he was delivering health and social care services across a wide population, but still on a small scale compared to working in the public sector.

He also told me he had felt he had to leave direct employment by the NHS in order to re-discover the values of the NHS. Of course, he is still delivering NHS services and in a highly flexible and responsive way - but he has the room for manoeuvre to use his imagination and the imagination of his other staff, and of course the imagination of the people he is delivering services to.

This seems to me what Karl Popper meant when he talked about “setting free the critical powers of man”. The very heart of modern Liberalism.

Will Post Office privatisation set free the critical powers of the people who work there? Believe that and you will believe just about anything.

Published on May 13, 2013 02:20

May 12, 2013

Lawson, Chamberlain and the Great Tory Faultline

Nigel Lawson is one of those strange, very successful individuals, who is often right in small things but has been staggeringly, stratospherically wrong in big things.

Nigel Lawson is one of those strange, very successful individuals, who is often right in small things but has been staggeringly, stratospherically wrong in big things.He was wrong about encouraging people into debt to buy homes (see my book Broke), wrong about the house price inflation that would result. He was wrong about Big Bang and about personal pensions. He has been horribly wrong about global warming (carbon dioxide levels hit 400 ppm for the first time this week). Now he is wrong about Europe and Britain's future.

Here are six reasons why he is wrong that we need to ditch the EU and throw in our lot trading with the Far East:

1. Long distance trade is going to get increasingly expensive as energy prices accelerate.

1. Long distance trade is going to get increasingly expensive as energy prices accelerate.2. Our biggest markets are in continental Europe and it seems bizarre to lock ourselves out of those privileges for the uncertainties of China.

3. It isn't clear why we should be any more successful trading with the Far East outside the EU than we are inside the EU.

4. To trade there, we particularly need manufacturing industry which - thanks to the high pound caused by the North Sea Oil era - we no longer have, at least not on the scale we need.

5. Given that, if we are intending to concentrate our trading efforts in financial services, then it will unbalance the UK economy even further and corrode our own real economy.

6. Trading primarily with the Far East will mean reducing wages to their level if our own services are going to be competitive, and this will exacerbate our economic problems.

But despite all this, the interventions of Lawson and Lamont this week will have a familiar ring about them for political historians, because the Conservative Party has always been split three ways on trade:

(a) Free trader internationalists looking for regulated markets (Kenneth Clarke, Damian Green and the pro-Europeans).

(b) Turbo-capitalism aficionados, looking for extreme de-regulation - not actually free trade in its traditional sense (see my blog on this) (Nigel Lawson).

(c) Mildly xenophobic nationalists, tariff reformers and Little Englanders (the UKIP tendency).

Most of the parliamentary Conservative party comes under the heading of (a) but

Chamberlain's campaign split the ruling Conservatives, and the government was held together entirely by the tenacity and skill of the Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, who kept his hands very close to his chest indeed. It was at this point that one of Balfour's closest allies described himself as having "nailed his colours firmly to the fence".

The chaos that ensued allowed the Liberals in with a landslide victory in 1906 so complete that it was able to lay the foundations of the welfare state.

Here are a few lessons we might do well to learn from that. First, there is nothing in common between (b) and (c) except a scepticism about the EU. Lawson and UKIP are actually pedalling very different political philosophies indeed, and this will become clear as UKIP sets out its stall.

Second, the Liberals won against Chamberlain by uniting the nation in favour of the old Liberal version of free trade, because it underpinned national prosperity, affordable food and world peace. That is how any defence of the European Union needs to be cast.

Published on May 12, 2013 02:39

May 11, 2013

Train fares, Legoland and the reason prices rise

Two things have made me feel poorer than I really wanted to yestoday. The first was a tweet by Steve Richards, the political columnist:

"On train to York. The ticket, not paid by me, is £249, second class. Can't get a seat."

Rather a familiar scenario that one. Of course, he has an open return, but we all used to get open returns not many years ago. A second class open return really isn't the height of aspirational luxury.

The second happened when I took my six-year-old to the barber's shop in Crystal Palace and found myself idling away my time reading the Sun, and there was an advert for their Saturday paper promising that they will be giving away two free tickets to Legoland in Windsor, worth - and here's the rub - £91.

Now, again I know there are cheaper ways of inserting your family into Legoland. You can book online and in advance and get ten per cent or so off the price. Perhaps a little more. I don't understand the complexities of the pricing system any more than I understand the complexities of rail ticket pricing.

But I admire the non-technological simplicity of Lego. My children have wanted to go to Legoland for months and talk about it most breakfasts (reminded by the Rice Krispies packet). But there is no way I'm going to go there if I can't get the family in for less than £150, and this seems unlikely.

I started this month writing about house prices and the rents the result, and the news today is that you need a salary of over £38,000 to rent a one-bedroom flat in London now. If house prices rise in the next 30 years as they have in the last 30 years, the average UK house - not London house - will cost £1.2m, as I explained in my book.

But the way that the financial elite have pushed up prices for everyone is far more widespread than simply a roof over the head. Because some business expenses run to £249 tickets to York, then the price rises that high. Because some families will pay £150 just to get into Legoland, then that is where the prices rise to. There are reduced price options for ordinary people - for the moment at least - and rules that allow us to afford to squeeze into these privileges, but that is what it is. Concessions.

It is strange that the world of foreign exchange trading and Big Bang, and all the privileges given to the financial elite, were given in the name of fighting inflation. That was the central objective of Margaret Thatcher's government.

Yet, in practice, the rapidly increasing gulf between us and them in our society is now fuelling inflation - until the point where many of us could no more afford a home in the neighbourhoods we grew up in than fly to the moon.

Inflation caused by too much money sloshing around the financial world - and by the blind eye turned to monopolies by successive governments. The rest of us live on concessions, as long as we are allowed to.

I rather set the cat among the pigeons with my Comment is Free piece in the Guardian this week called 'Why everyone needs the middle class'. There were more than 800 comments on the end of it, so I know this is just at the beginning of a wider debate. But I am trying to construct a political narrative that can attract right and left - because that seems to me to be the only way of making anything happen.

It is the only way that, paradoxically, we can rein back some of those accelerating prices, and break out of the little box made for most of us marked 'concessions'.

"On train to York. The ticket, not paid by me, is £249, second class. Can't get a seat."

Rather a familiar scenario that one. Of course, he has an open return, but we all used to get open returns not many years ago. A second class open return really isn't the height of aspirational luxury.

The second happened when I took my six-year-old to the barber's shop in Crystal Palace and found myself idling away my time reading the Sun, and there was an advert for their Saturday paper promising that they will be giving away two free tickets to Legoland in Windsor, worth - and here's the rub - £91.

Now, again I know there are cheaper ways of inserting your family into Legoland. You can book online and in advance and get ten per cent or so off the price. Perhaps a little more. I don't understand the complexities of the pricing system any more than I understand the complexities of rail ticket pricing.

But I admire the non-technological simplicity of Lego. My children have wanted to go to Legoland for months and talk about it most breakfasts (reminded by the Rice Krispies packet). But there is no way I'm going to go there if I can't get the family in for less than £150, and this seems unlikely.

I started this month writing about house prices and the rents the result, and the news today is that you need a salary of over £38,000 to rent a one-bedroom flat in London now. If house prices rise in the next 30 years as they have in the last 30 years, the average UK house - not London house - will cost £1.2m, as I explained in my book.

But the way that the financial elite have pushed up prices for everyone is far more widespread than simply a roof over the head. Because some business expenses run to £249 tickets to York, then the price rises that high. Because some families will pay £150 just to get into Legoland, then that is where the prices rise to. There are reduced price options for ordinary people - for the moment at least - and rules that allow us to afford to squeeze into these privileges, but that is what it is. Concessions.

It is strange that the world of foreign exchange trading and Big Bang, and all the privileges given to the financial elite, were given in the name of fighting inflation. That was the central objective of Margaret Thatcher's government.

Yet, in practice, the rapidly increasing gulf between us and them in our society is now fuelling inflation - until the point where many of us could no more afford a home in the neighbourhoods we grew up in than fly to the moon.

Inflation caused by too much money sloshing around the financial world - and by the blind eye turned to monopolies by successive governments. The rest of us live on concessions, as long as we are allowed to.

I rather set the cat among the pigeons with my Comment is Free piece in the Guardian this week called 'Why everyone needs the middle class'. There were more than 800 comments on the end of it, so I know this is just at the beginning of a wider debate. But I am trying to construct a political narrative that can attract right and left - because that seems to me to be the only way of making anything happen.

It is the only way that, paradoxically, we can rein back some of those accelerating prices, and break out of the little box made for most of us marked 'concessions'.

Published on May 11, 2013 03:28

May 10, 2013

A six-point plan for a Liberal populism

Years ago, I happened to come across a set of statistics that related to self-employment, broken down by parliamentary constituency. I had always believed there was some correlation between independence and Liberal-mindedness, and here it was in black and white: most of the top ten constituencies for self-employment were bastions of political Liberalism too.

Years ago, I happened to come across a set of statistics that related to self-employment, broken down by parliamentary constituency. I had always believed there was some correlation between independence and Liberal-mindedness, and here it was in black and white: most of the top ten constituencies for self-employment were bastions of political Liberalism too.I thought this was rather important and happened to come across the Lib Dem leader a few days later (I won't say who in case this seems like a criticism, which it isn't) and told him about it. He wasn't nearly as enthusiastic about this revelation as I was.

"We don't want to be Poujardist about it," he said.

Now Pierre Poujarde, for those who weren't politically aware in the 1950s (I certainly wasn't), led a populist revolt in France by small shopkeepers and eventually found himself elected to parliament (Le Pen was his youngest elected deputy). Poujardism has become a byword for the kind of xenophobic, anti-intellectual populism, based on a squeezed lower middle class, that most terrifies the political establishment. Not for nothing did Poujarde call the French National Assembly the "biggest brothel in the world". There is a sort of UKIP whiff about it all.

Fear of Poujarde and his kind makes the conventional political parties - with their technocratic graphs - particularly vulnerable to movements like UKIP, when they are intelligently led.

But I've been asking myself whether it might be possible to construct a populist Liberalism capable of taking on the Poujardists and beating them. Here is my six-point plan for doing so.

1. Take a deep breath, make a pot of tea and do a great deal of talking - preferably to some regular users of public services - claimants, parents of children in failing schools, and/or people with long-term health conditions. Take notes.

2. Accept the full truth: many, if not most, of our public institutions have been hollowed out by poor management, bone-headed IT systems and centralised targets - and are only kept alive by the courage and devotion of frontline staff.

3. Order the collected writings of Ivan Illich (see photo above) and read them, and imagine what kind of policies one might hammer out if he had been right - and institutions really did have the opposite effect to their declared purpose.

4. Take a second look at the euro, and ask yourself again whether the same interest rate can possibly suit every part of the continent of Europe - and (be honest now) whether it might actually have encouraged the Poujardists after all (difficult, that one).

5. Take a blank sheet of paper and work out an emergency plan for providing people with the energy, healthcare, education and support they would need if conventional channels suddenly became impossible.

That's 5. But you said a six-point plan? I know, but I haven't worked out the sixth point yet. Please give me a hand, anyone who happens to stumble across this.

The key difference between conventional politicians and populists is not hatred - you don't have to hate to be a populist. It is the understanding that our institutions are no longer effective. These are the very institutions so beloved of conventional politicians who play their tweaking games and look at their wholly irrelevant statistics - unaware that the statistics machine has become disconnected from the frontline thanks to Goodhart's Law.

What I'm saying is that the essence of populism isn't xenophobia, it is scepticism about our institutions, just as UKIP tend to be a little sceptical of the EU (I put this gently).

That is the key central truth of populism. It is also their strength. It enables them to portray themselves living in the real world, rather than in Westminster - where things still seem to work - as realists in a world of illusion. It is also a strength because it is largely true.

And if you don't believe me, read my book The Human Element . Or if you can't face that, try Harriet Sergeant's brilliant account of gang life in Brixton, and see the reality of these expensive institutions, paid for by taxpayers on the ground, but achieving so little when it really matters.

Because, it seems to me, that unless Lib Dems do this - or somebody else with an enlightened outlook - then the Poujardists will get the edge.

Published on May 10, 2013 01:36

May 9, 2013

Whatever you do, don't mention the word 'class'

This morning, I had a go at setting out some of the strange experience it has been writing on class. You can read it on Lib Dem Voice:

http://www.libdemvoice.org/opinion-can-the-middle-classes-get-some-political-clout-34450.html

There was I trying to weave a new political narrative that could potentially unite most classes behind it, and the interest and support has been wonderful - but the abuse has been extraordinary too. I got 750 comments on my Comment is Free article for the Guardian earlier in the week, some of them supportive, some of them downright insane.

Part of the problem seems to me that any mention of class on a book cover seems to absolve some people from reading the book before coming to a conclusion about it. I have heard from people from every part of the political spectrum - some of whom fundamentally disagree with the thesis that we are heading to a controlled and struggling proletarian society, controlled by a powerful mega-wealthy elite at the top. Some of whom agree, but don't mind as long as the middle classes get wiped out. Some of them, well, don't let's go there...

The real issue is why the mainstream political parties no longer represent the middle classes - we already know they don't represent the working classes. The coalition got the rhetoric right back in 2010 with the ambition to 're-balance' the economy, but seem unable to find any effective levers they can agree on to do so.

Mainstream policy still seems to be designed to recreate the conditions of the last bubble, and to allow the very wealthy to hoover up even more money - apparently on the grounds that the City pays quite a lot of tax (a recipe for increasing inertia and dependence).

The ineffective banking oligopoly still rides high. There is still no community banking infrastructure as other countries have. Local government has been set free by the Localism Act and other measures, but many of their leaders are still waiting hopefully to be bailed out by central government or external investors - rather than acting to make their local economies work.

It is all very frustrating. And into the middle of this spins a populist force, with no apparent interest in the economy - but riding the frustrations caused by its failure - and encouraging the mainstream politicians to look elsewhere at our fraught relationship with Europe as the source of all solutions.

"So stupid in politics," said George Bernard Shaw of the middle classes. But imagine they did grasp how they are being priced out by the elite, and decided to act politically - to hammer out a series of policies that genuinely promised a sustainable income and a roof over the head for the next generation.

What would happen then?

http://www.libdemvoice.org/opinion-can-the-middle-classes-get-some-political-clout-34450.html

There was I trying to weave a new political narrative that could potentially unite most classes behind it, and the interest and support has been wonderful - but the abuse has been extraordinary too. I got 750 comments on my Comment is Free article for the Guardian earlier in the week, some of them supportive, some of them downright insane.

Part of the problem seems to me that any mention of class on a book cover seems to absolve some people from reading the book before coming to a conclusion about it. I have heard from people from every part of the political spectrum - some of whom fundamentally disagree with the thesis that we are heading to a controlled and struggling proletarian society, controlled by a powerful mega-wealthy elite at the top. Some of whom agree, but don't mind as long as the middle classes get wiped out. Some of them, well, don't let's go there...

The real issue is why the mainstream political parties no longer represent the middle classes - we already know they don't represent the working classes. The coalition got the rhetoric right back in 2010 with the ambition to 're-balance' the economy, but seem unable to find any effective levers they can agree on to do so.

Mainstream policy still seems to be designed to recreate the conditions of the last bubble, and to allow the very wealthy to hoover up even more money - apparently on the grounds that the City pays quite a lot of tax (a recipe for increasing inertia and dependence).

The ineffective banking oligopoly still rides high. There is still no community banking infrastructure as other countries have. Local government has been set free by the Localism Act and other measures, but many of their leaders are still waiting hopefully to be bailed out by central government or external investors - rather than acting to make their local economies work.

It is all very frustrating. And into the middle of this spins a populist force, with no apparent interest in the economy - but riding the frustrations caused by its failure - and encouraging the mainstream politicians to look elsewhere at our fraught relationship with Europe as the source of all solutions.

"So stupid in politics," said George Bernard Shaw of the middle classes. But imagine they did grasp how they are being priced out by the elite, and decided to act politically - to hammer out a series of policies that genuinely promised a sustainable income and a roof over the head for the next generation.

What would happen then?

Published on May 09, 2013 04:41

May 8, 2013

Towards a bit of human-by-default

I'm not of course accusing the Government Office for London (GOL) of anything of the kind, but I must say I did think of Gandhi when I walked past the site of their plush offices at the north end of Vauxhall Bridge, to find the whole building gone.

For those of us who suffered under their boneheaded rule - especially in the voluntary sector during the Blair years - the demolition of their building is a much-deserved fate. If they had acted like a regional office ought to, drawing down powers from central government and spreading it around, then maybe I would have felt a moment's regret. In fact, they went the other way, taking powers from local government and inserting their own miserable brand of utilitarian targets.

This is what I said in a speech on the subject in Coventry in 2006:

"This is the world the voluntary sector has stumbled into by accepting the task of delivering government services – or should I say delivering outputs. It’s a delusory world where nothing is quite what it seems. Where outputs are more important than achievements. Where every charity has targets imposed by funders who have their own miserable yoke of targets to deliver as well. Big fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite them.

And each time the bites are passed down, they get tougher and more intransigent. So while the mandarins at the Treasury can be relatively relaxed about the standard of proof they require before acting, those Whitehall targets descend via funder to funder. Until they reach the bottom flea – the poor charity which has to make something happen on the ground – by which time they have become a gradgrindian nightmare which bear no relation to reality.

“If you can’t prove it, we can’t pay for it,” one of our time banks was told by their funder, the ultimate beneficiary of the Stalinist systems that emanate from the Government Office for London. But they can’t prove it. How can they prove it? All they can do is desperately mould the reality into the targets."

Never in the field of human government has one agency frustrated so much. The sad thing is that, although the coalition has grasped some of the problem with targets - the inflexibility, the failure of target systems to deal with variety - they haven't actually followed that insight through. We have payment-by-results, which turbo-charges the target effect. And we have 'digital by default', which - although it isn't exactly about targets - it also fails to deal effectively with the variety of humanity, because it reduces people to a set formula that may work sometimes but often won't.

The cognoscenti will realise that I am relying here on the approach pioneered by the systems thinker John Seddon. I wonder if he ever encountered the terrifying GOL inaction machine.

All of which brings me to an amazing blog which pedals a similar view called systemsthinkingforgirls, including this particular post called Human By Default, the antidote to digital by default, which the anonymous author defines as:

"human services that are so human that they work well for all humans”.

I absolutely agree, and I tried to say something similar - at rather greater length - in my book The Human Element. Human beings are much more flexible than systems and they have a great advantage: they can make change happen by building relationships. Any digital by default policy that excludes this where it matters will redouble long-term costs.

Perhaps someone should put up some kind of memorial to inhuman systems on the site. If only I could be sure that GOL-style target culture was actually dead.

Published on May 08, 2013 02:51

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.