David Boyle's Blog, page 84

April 17, 2013

Whose side is Toby Young on?

Well, I enjoyed being on the receiving end of a Toby Young review on Sunday. Kind of.

Well, I enjoyed being on the receiving end of a Toby Young review on Sunday. Kind of.Of course, I realise he is busy - probably too busy to take in everything he reads in all the books he reviews. But I'm absolutely sure he has taken in the back cover, perhaps some of the first chapter. And he definitely took in part of the last chapter, too, of my new book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? What more can you ask of a busy man?

You can see for yourself in last Sunday's Mail on Sunday, but it isn't online or I would link to it. It was called 'Time up for Mr and Mrs Average'.

What is more, I absolutely agree with him. The middle classes ought to survive because of their thrift, public-spiritedness and reverence for education.

What was a bit peculiar is that he hadn't taken in enough of what he read to discover that we are of one mind on the subject. He seemed to think otherwise.

It is true that I'm not absolutely sure about thrift - I'm not convinced it survived the invention of the credit card. But, as he should have discovered, I have a whole chapter on the reverence the middle classes have for education. As for public-spiritedness, it is precisely the ability and willingness of the middle classes to make things happen that makes them so important, as I say many times. This is what the book says:

"Despite their reputation, the middle classes have actually presided over a period of unprecedented tolerance in British life, embracing a society that – despite the difficulties – is more and more diverse and multiracial, more and more tolerant of the peculiar way that people live, if they are not harming anyone else. And if this was not led by the middle classes, who was it led by?"

I have always rather admired Toby Young, so I was glad to have him onside (even if he wasn't sure if he was). I am a lonely supporter of free schools in the Lib Dems. I endlessly applaud his efforts to kick-start a movement of experimental school plantations.

Where I take issue with him is that, instead of ploughing on through the book - and, hey, he's a got a school to run - he decided that, because I had some kind of link to the party, my argument must be typically Lib Dem. I only wish it was - but tackling monopolies, starting an entrepreneurial revolution, rolling out free schools and creating debt-free money have yet to come within a whiff of the last Lib Dem manifesto, despite my best efforts.

So it is a pity Toby read without inhaling because we need to have this debate, and the future of the middle class seems to me to depend on it.

And there are a whole range of other reasons - political and economic stability, cultural underpinning and much else besides - why it would matter very much if the middle classes began to disappear into a proletarian struggle for survival.

So, here's the question, Toby. Do you agree with me that the middle classes are vital to save? Do you agree they are under intense pressure, maybe not uniquely, but still having an increasingly difficult time? Do you agree that the next middle class generation will struggle to afford a roof over their heads? Or is everything fine?

Published on April 17, 2013 02:35

April 16, 2013

The great Tory welfare contradiction

I must admit I had a small moment of relief, even pride in the Lib Dems, when I heard that Vince Cable had resisted calls to prevent him from raising the minimum wage for apprentices - as well as for everyone else.

The adult minimum wage is now raised to £6.31. It is still below the level it needs to be to make it a 'living wage', and until it is, the government will still be subsidising employers, which is a ridiculous position to be in. Old-fashioned Liberals like me still cling to the dream, not just of a minimum wage, but a basic income paid by right of citizenship, allowing us to dismantle the bureaucracy of welfare, partly at least.

But that, as Rudyard Kipling would say, is another story. Certainly another argument.

What is significant is that Vince Cable raised the minimum wage on the very day that the benefits cap was introduced in a few experimental areas in London (in Mrs Thatcher's day, they used to experiment on Scotland; now it is London).

Is this deliberate on his part? If not, it should have been, because it reveals a deep contradiction in the traditional Conservative position on unemployment. They have two propositions, both of which are true:

It must pay people to come off benefits and get a job, otherwise the welfare system continues to trap people in dependency.People in jobs must not price themselves so highly that they can't get a job.Both of these are quite correct, but - in practice, taken together - they contradict each other once they are put into effective policy. It means either that we should lower the level of benefits so that it pays to take a job (the justification for the benefits cap) or we should lower wages to make people more employable (the Conservative backbench position on the minimum wage).

In practice, one policy renders the other one impossible. Doing both together would instigate a miserable, self-defeating race to the bottom, where welfare payments keep being cut to undercut falling wages.

The truth is that wages are already far too low to sustain a prosperous economy. It is self-defeating to reduce them to Far Eastern levels because the demand would then disappear from our own economy, and - when boardroom pay went up 49 per cent in 2010 alone - this seems unlikely to have much leadership and example behind it.

In practice, you can't cut welfare benefits and wages and expect to achieve both outcomes. There is the Great Contradiction.

The problem of low wages is at least part of the problem about the benefits trap. When around a fifth of people working in the UK are not earning a 'living wage', then we have a problem - and the problem is that tax-payers is expected to subsidise employers, and I don't see why we should.

Nor is this a problem that is confined to the low paid, given that inflation is now rising at a rate twice that of wages. The effect it is having on the middle classes, and whether they can survive at all, is the subject of my book (out next week) Broke: Who killed the middle classes?

The adult minimum wage is now raised to £6.31. It is still below the level it needs to be to make it a 'living wage', and until it is, the government will still be subsidising employers, which is a ridiculous position to be in. Old-fashioned Liberals like me still cling to the dream, not just of a minimum wage, but a basic income paid by right of citizenship, allowing us to dismantle the bureaucracy of welfare, partly at least.

But that, as Rudyard Kipling would say, is another story. Certainly another argument.

What is significant is that Vince Cable raised the minimum wage on the very day that the benefits cap was introduced in a few experimental areas in London (in Mrs Thatcher's day, they used to experiment on Scotland; now it is London).

Is this deliberate on his part? If not, it should have been, because it reveals a deep contradiction in the traditional Conservative position on unemployment. They have two propositions, both of which are true:

It must pay people to come off benefits and get a job, otherwise the welfare system continues to trap people in dependency.People in jobs must not price themselves so highly that they can't get a job.Both of these are quite correct, but - in practice, taken together - they contradict each other once they are put into effective policy. It means either that we should lower the level of benefits so that it pays to take a job (the justification for the benefits cap) or we should lower wages to make people more employable (the Conservative backbench position on the minimum wage).

In practice, one policy renders the other one impossible. Doing both together would instigate a miserable, self-defeating race to the bottom, where welfare payments keep being cut to undercut falling wages.

The truth is that wages are already far too low to sustain a prosperous economy. It is self-defeating to reduce them to Far Eastern levels because the demand would then disappear from our own economy, and - when boardroom pay went up 49 per cent in 2010 alone - this seems unlikely to have much leadership and example behind it.

In practice, you can't cut welfare benefits and wages and expect to achieve both outcomes. There is the Great Contradiction.

The problem of low wages is at least part of the problem about the benefits trap. When around a fifth of people working in the UK are not earning a 'living wage', then we have a problem - and the problem is that tax-payers is expected to subsidise employers, and I don't see why we should.

Nor is this a problem that is confined to the low paid, given that inflation is now rising at a rate twice that of wages. The effect it is having on the middle classes, and whether they can survive at all, is the subject of my book (out next week) Broke: Who killed the middle classes?

Published on April 16, 2013 04:41

April 15, 2013

Naval strategy lessons for the NHS

It is the evening of 1 August 1798, in a sticky Mediterranean dusk, and Horatio Nelson’s Mediterranean Fleet has finally tracked down their French opponents at anchor in Aboukir Bay on the Egyptian coast. He is determined to bring them to action, even in the gathering gloom.

It is the evening of 1 August 1798, in a sticky Mediterranean dusk, and Horatio Nelson’s Mediterranean Fleet has finally tracked down their French opponents at anchor in Aboukir Bay on the Egyptian coast. He is determined to bring them to action, even in the gathering gloom.The British gun crews are crouching by their cannon while their French counterparts heave their heavy armaments onto the seaward side where the British will come. The Battle of the Nile is about to begin.

Nelson had prepared for this battle by setting out clear rules of engagement, discussed with his captains evening after evening around his table on the Vanguard. That was the broad plan; the details would have to take care of themselves as circumstances arose, and he trusted his captains to interpret the plan effectively.

Nelson was no disciplinarian, and he had already gained a reputation for disobeying orders during the Battle of St Vincent. He steered out of line because he saw the chance to cut off a group of Spanish ships from the rest, and managed to capture them. Even if this wasn’t explicit, his captains knew this was his style and it was what he expected of them – not slavish obedience to detail, but enthusiastic commitment to the objective.

These regular dinners were the beginning of the trusting collegiate atmosphere he managed to instil among his commanders, which gave rise to the idea of a ‘band of brothers’.

Captain Thomas Foley in the Goliath happened to be leading the line when the French came into sight, he ordered his men to get the battle sails ready, so that he could stay in front when the order came to get into line of battle.

So it was Foley, standing next to his helmsman, the battle ensigns flying behind him, who saw the emerging opportunity as the disposition of the French ships became clear. There they were anchored along the shore, and he realised there might just be enough space to squeeze along their undefended side, between the French line and the shore itself.

It was a risky decision. Thinking fast as the battle got ever nearer, Foley realised that Bruey’s ships must have anchored with enough space to swing round at anchor as the tide changed, so there would almost certainly be enough sea to avoid running aground. But there was no time to consult anyone else. Foley steered between the French ships and the shore leading the British line after him. Foley was rightly hailed as the hero of the victory at Aboukir Bay of which Nelson had been the architect.

So although Nelson laid down the framework for the battle, with regular dinners for his captains, making sure his intentions became second nature to them, Foley knew he was allowed to do something entirely different if he saw an opportunity. He was able to break with conventional thinking, and the apparent drift of his orders, and use his intuition. Would he have managed to win the battle if he had been governed by the management culture from British public services two centuries later? Hard to know, but probably not.

The point was that he knew he had to take the decision, knew he was expected to, felt confident to do so, and did so in style.

Fast forward nearly a century to 22 June 1893, but again to the British Mediterranean Fleet, by then the decisive force in global military affairs. By that time, the Royal Navy revered the name of Nelson and paid lip service to his cult of structured disobedience – the telescope to the blind eye and everything that went with it – but had rather forgotten what it meant.

Nelson’s successor as commander was Admiral Sir George Tryon, charming on the dinner party circuit but known as a dictatorial martinet when he was at sea. He tried to keep his intentions hidden from his subordinates to help them practice in unpredictable situations but, the day before this fatal incident, he had actually told his captains what he wanted to do.

He was going to turn his two columns of ironclads towards each other before they anchored for the night. It was a risky manoeuvre. Some brave captains suggested that, given the turning circles of the ships, the columns ought to be at least 1,600 yards apart when they started to turn. It wasn’t quite clear whether Tryon had agreed.

When the time came, off the coast of what is now Lebanon, Tryon unexpectedly ordered the two columns to start turning when they were only 1,000 yards apart. Two officers queried the order, but he snapped at them to get on with it. Admiral Hastings Markham, leading the other column, was confused by the dangerous signal and delayed his acknowledgement. “What are you waiting for?” signalled Tryon.

What was going to happen seemed horribly apparent to everyone except Tryon, but nobody acted to prevent it. Three times, the flag captain of his flagship Victoria asked for permission to go astern as the two leading ships hurtled towards each other, but did nothing. Only at the last minute, as Markham’s flagship Camperdown hurtled towards the Victoria with its ram below the waterline, Tryon shouted ‘Go astern, go astern!”

It was too late. There was a grinding crash as the Camperdown’s ram buried itself in the flagship. Victoria capsized and sank thirteen minutes later. As many as 358 sailors lost their lives. One of them was Tryon, who was said to have appeared mysteriously to his wife and guests at a dinner party in Eaton Square at his moment of departure.

These two stories, both about the commanders of the British Mediterranean Fleet, provide a blueprint for different organisational styles. Hospitals are not quite the same as fleets but, even so, organisations run by Nelsons tend to work, and those run by Tryons tend not to. Tryon organisations can get by, but never quite in the brilliant ways that the Nelson organisations do.

Ironically, the ill-fated Tryon was always known as a brilliant and innovative strategist. His fatal flaw was his authoritarian style of leadership, which left those who would have been in his band of brothers – if he had been Nelson – fatally in the dark. They could see the details of what they were supposed to do, but not the big picture. There they were, flailing around, not daring to act to avoid disaster even though they could see it coming.

The situation was extreme, one ironclad with a ram bearing down on another, but it is also familiar. We have all worked for organisations where a similar culture prevails, where disaster looms and most people decide it is probably best to say nothing.

We could say things that would improve services or performance or avoid accidents or disasters, but it is less risky to keep quiet. Maybe this doesn’t matter so much running fast food franchises or corner shops, but in hospitals it matters very much indeed. And in the NHS as a whole.

I've set out these things in response to Roy Lilley's excellent blog on Letting-Go Management in the NHS. He is absolutely right:

"Our-NHS is going to go through a tough time, instinctively some managers will think they have to become tough. They think tricky times and hard decisions call for tough management. Not true."

That is an urgent message for the NHS. What it so badly needs, to find the creativity and innovation - and I may say, also the savings - is the maximum dose of flexibility, to set people free to solve problems in the best way that suits local people. More about this naval parallel in my book The Human Element.

Published on April 15, 2013 02:32

April 14, 2013

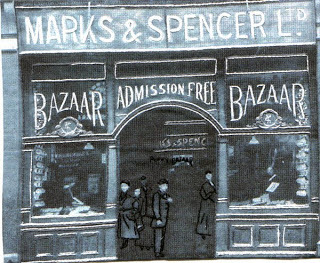

Why M&S can't claw their way back

Between 1880 and 1910, a third of all the Jewish people on the world were moving continents, squeezed into dirty, lice-infested, black-funnelled steamships, arriving in London Docks or Ellis Island in New York Harbour, hoping for a new world, often owning nothing more than they were wearing.

Between 1880 and 1910, a third of all the Jewish people on the world were moving continents, squeezed into dirty, lice-infested, black-funnelled steamships, arriving in London Docks or Ellis Island in New York Harbour, hoping for a new world, often owning nothing more than they were wearing.One of them was Michael Marks, who seems to have decided on England because his older brother Barnet had gone there first. But as Michael arrived in London in 1882, with enough money for the train to Stockton-on-Tees, he found that his brother had gone – or was going – to the Yukon to join in the gold rush. Barnet also went into retailing and opened a successful shop in Dawson City. Something about the Marks family seems to have put retailing in their genes.

So there was Michael, without language, money or prospects, but with something else. There was clearly something about the family that drove them to sell, and here he had arrived in the right place at the right time.

There was a retailing revolution under way, to serve the growing middle classes in their new urban terraced homes, like Mrs and Mrs Pooter in Upper Holloway, with a little yard at the back and maybe a housekeeper and maid. There was a wealth of cheap manufactured goods now on the market, filtering through to the upwardly mobile working classes, whose incomes were steadily improving throughout the 1880s.

It was 1884 before he acted, the year of the siege of Khartoum, of Huckleberry Finn and the Fabian Society. He decided to move to Leeds, a burgeoning Yorkshire city, with a population of 300,000 clustered round the railway line to London. He particularly chose the district of the Leylands, with its strong Jewish population steeped in the clothing trade. Here he was going to stake his claim to the new world, and here – lo and behold – he encountered the help he needed.

The local wholesaler Isaac Dewhirst was wandering along Kirkgate one morning when he was approached by a man who said just ‘barons’. Realising this apparition spoke no English, he turned to his manager who spoke Yiddish and discovered the he was looking for Barran Clothiers, which was known to give work to refugees.

It was a lucky coincidence. Dewhirst was fascinated by Marks and offered him to lend him £5. Marks asked instead if he could take the money in the form of goods and pay off the cost in instalments. Dewhirst agreed, and Marks became an itinerant salesman in the Yorkshire Dales, selling buttons, wool, tablecloths, sacks and socks. It is a measure of the slightly unworldly company that Marks was about to found that the firm of I. J. Dewhirst and its successors are still supplying them to this day.

Marks was a damn good pedlar, but it was an exhausting business. Market halls were to the working classes what department stores were to the middle classes. They were all-weather affairs. You could buy nearly everything under one roof, and they were cheap.

But Marks had a language problem. He solved it by laying out all his goods on the table, rather than keeping the bulk of them under it, so that people could handle what they were about to buy, rather than ask questions about it. He also began what became the credo of his company.

He avoided long haggling conversations with the customers, by classifying everything according to price. Above the section for penny goods, he coined what became one of the most successful advertising slogans ever invented: ‘Don’t ask the price, it’s a penny’. A strategy being adopted even now by the poundshops.

So began the company which became Marks & Spencer, which - under Michael's driven son Simon - eventually sold a quarter of all the men’s pyjamas and underwear and children’s socks in the nation, and a third of the bras, boy’s underwear and children’s dressing gowns.

I describe all this in the light of the latest figures which shows M&S's clothes offering still sinking. You can find out more of the bizarre history of the company in my book Eminent Corporations.

The big question is, where did they go wrong? The answer, it seems to me, is they kept on listening to the siren voices of those telling them to appeal to everyone, and especially the trend-setting young. Hence the terrible mix of children's clothes you find there now, covered in logos and desperately trying to be trendy - while John Lewis has usurped their place as clothing providers to the middle classes.

That and their terrible fall from grace in the 1990s, betraying the UK textiles industry - and all the links with trusting suppliers that had made the company so innovative - not to mention the vacuous pursuit of share price at the same time, the last resort of those without strategy.

It is a sad story and I wonder whether they can recover their position. My feeling is that John Lewis is a mutual, and is therefore bound to be more successful. In the end, the mutual going head to head with a hierarchy is bound to win - and M&S was always the most hierarchical company.

This is an important experiment to make. Because being dependent on the financial markets now looks like the kiss of death for UK companies - the precise opposite of what we have been told for the past generation.

Published on April 14, 2013 01:50

April 13, 2013

Who authorised the Thatcher military funeral?

The British political processes are a stupendous thing. You should never under-estimate their ability to seize on some symbolic element of what might be something quite important, and worry it to death - and then, when they have solved it, think that somehow the whole issue is now resolved.

Something similar seems to be happening over the completely pointless row over the Ding, Dong song. It is pretty tasteless to celebrate a death, and perhaps the BBC is in a difficult position - I don't know. But really, on the storm in a teacup scale, this is about Force 8.

But there is an underlying issue which has barely had a look in.

Even if Margaret Thatcher was the giant figure that she is being painted, and I am not at all sure that is the way history will see it. Yes, there were major changes that took place during her time, but I am unsure whether they are really down to her. There are some important and terrifying side-effects as well, as I have argued here before.

Even if she was, I feel increasingly uncomfortable that the whole celebratory mechanisms of the state are being rolled out to mark her death - the Queen, the military, gun carriages. These things very occasionally happen with politicians: the Duke of Wellington (see picture) defeated Napoleon, Winston Churchill united Europe against the Nazis. Whatever else you might accuse Margaret Thatcher of - uniting people isn't one of them.

I believe in the monarchy. Call me old-fashioned, but I believe it is a vital buttress against fascism and extremism. When you organise the state institutions as if we were a presidential republic, it undermines those institutions that stay above the fray.

So here's the key question. Who authorised this embarrassing and inappropriate military funeral and when?

I think we should be told.

Published on April 13, 2013 03:50

April 12, 2013

Why class really isn't about money

We may not think about class much these days, but the Today programme obviously does - returning to the theme yet again this morning (0855), and enjoying the thought that George Orwell identified himself as "lower upper middle class".

We may not think about class much these days, but the Today programme obviously does - returning to the theme yet again this morning (0855), and enjoying the thought that George Orwell identified himself as "lower upper middle class".It is conventional to say, as Juliet Gardiner did this morning, that we are confused about class. I'm not sure we are, but the BBC is: it seems to think that class is all to do with income.

That is why the Great Class Calculator identifies me as 'traditional working class' - because it is old-fashioned enough to equate my miniscule earnings as a writer with my class. This is what I wrote about doing the survey last week.

Earnings just confuse the issue. One recent study in 2008 found that 48 per cent of those calling themselves ‘working-class’ earned more than the average salary and a quarter of them earned more than £50,000 a year. In some cities (Leeds for example) people calling themselves working-class are better off than those who see themselves as middle-class. A third of bank managers in one recent survey identified themselves as working-class.

This isn't about income, it is about background and culture - and maybe values. The fact that the BBC is pedalling a calculator that emphasises income is a measure of how much traditional middle class values, of thrift, deferred gratification and independence, are under assault from the new class of Masters of the Universe in financial services.

None of this implies that working class values are any the less important, but they emphasise different things - community, mutual support and dignity. Or they did. These are under an even more powerful assault from above.

These things are important. Middle class values, often caricatured, sometimes a caricature of themselves, were shaped quite deliberately by writers like William Cobbett in the 1820s who saw the new class emerge, and were determined that it should strike out in a new moral direction, away from the dissipated aristocracy who gambled, drank, bullied and horsewhipped their way through life.

The middle classes were designed, in that respect at least, as an antidote to ruling class, ubermensch culture. That is why it is so important that they are defended now, when the possibility of our independence is being corroded.

It is also why I, for one, am determined to argue that there is a fundamental difference beyond income between the old classes and our new overlords - it isn't just that we are the same but poorer.

More about this, and why it is so important, in my forthcoming book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes.

Published on April 12, 2013 02:43

April 11, 2013

How to save public services

I have a feeling that history will see these years in the UK rather differently to the way we see them now.

I have a feeling that history will see these years in the UK rather differently to the way we see them now. We imagine that austerity will dominate the history books. In fact, I have a feeling that the real issue will turn out to be something different - it is whether or not we grasp the urgency of the need to save our public services, the NHS and the rest of the caboodle.

In that sense, the present round of cuts are barely relevant compared to what is coming - not just here but in most western countries. What with Barnet's Graph of Doom and the various Wanless Reports warning about the future of the NHS, the clues have been there for some time. Demand is rising so fast, costs are rising so fast, and the last decade or so have equipped our services with a series of reforms so expensive and sclerotic that they may kill the patient.

And at the same time, the economy is going to carry on struggling, as the focus of the world shifts eastwards.

It is extraordinary, given this scenario, just how tame the debate is. The right just wants to privatise, when profits are going to be pretty scarce, and anyway rather begs the key question. The left just wants to go back to 1945, to what is arguably the original flawed design that has led us here - the disempowering idea that grateful passive consumers have their needs attended to by busy professionals.

Where is the real debate we need if we are going to protect the kind of society that looks after itself?

I found myself wondering this on Tuesday when I spent much of the day at the very impressive NESTA seminar on People-Powered Health, the not-quite-final hurrah of their ambitious project to apply the ideas behind 'co-production' to long-term conditions - the most expensive, least successful aspect of NHS work.

The central message is that we have missed the critical untapped resource - the users of the system, their families and neighbours.

Conventional thinking suggests that this approach - from peer support to co-delivery - is fraught with dangers and compromise. Actual experience, as described in a series of films which the People-Powered Health team made, is that it can be transformative, changing the power balance between people and professionals.

Part of the problem is that politicians and policy-makers regard the public as pretty apathetic. When it comes to sitting on committees - which politicians regard as the highest form of existence - they may be right. But there is a huge untapped demand from patients and service users to use their time and human skills to help other people, as long as it is in some way mutual.

It would be glib to say this is the only way out of the coming crisis, but it is an absolutely vital part of the jigsaw. The trouble is that there is what one speaker called a "huge coalition of inertia" when it comes to rolling out change.

But I did find out one absolutely vital piece of information at NESTA. Their calculations, based on a range of studies, is that People-Powered Health along these lines will cut NHS costs by at least 7 per cent and maybe up to a fifth. Even 7 per cent comes to £4.4 billion.

Published on April 11, 2013 01:18

April 10, 2013

Was Margaret Thatcher really English?

“The Saxon is not like us Normans. His manners are not so polite.

But he never means anything serious till he talks about justice and right.

When he stands like an ox in the furrow – with his sullen set eyes on your own,

And grumbles, ‘This isn't fair dealing’, my son, leave the Saxon alone.”

That is the start of the Kipling poem which Margaret Thatcher took with her to her first European summit, where she had resolved to batter the other European nations into giving Britain a rebate.

It shows just how much she was aware of herself as an Anglo-Saxon, and I must admit I rather admire her for it in retrospect. In retrospect, as Jonathan Calder said, I feel a little sad at the end of an era. Though a few years ago, I cured myself of this sneaking feeling by opening a copy if her memoirs in a bookshop, and suddenly the full irritation with her aggressive ability to batter a handful of half-truths rushed back to me.

Yesterday, I blogged about one peculiar irony about her rule – how it had begun with the idea of a property-owning democracy yet sowed the seeds of a situation where nobody can afford to buy a home except the mega-rich.

But there is an even more fundamental paradox about the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, and it was about how truly representative she was of those Anglo-Saxon values she claimed.

Because the actual direction of travel wasn't Anglo-Saxon self-determination and the apotheosis of small platoons at all. It was a disastrous centralised rule from Whitehall, sometimes of the most corrosive and aggressive kind.

This was justified partly by contempt for local government, and perhaps an understandable rage at what the big cities had done to their own inner areas; also perhaps a determination to force the pace. The result was certainly a speedy pace, but also a legacy of learned helplessness by the cities, a damaging inability to make things happen, a horror of innovation and an abiding sclerosis where it really matters – at local level.

There is the great irony. She went into battle in defence of Anglo-Saxon values but ended up creating a Napoleonic state, in the image of the great centralised states of the continent – which, one by one, have seen the error of their ways and reformed. The UK has only just begun to fight its way out.

So two points here. One is the Liberal approach: a revival of those very local institutions that she had so little time for, local organisations that can make things happen.

You can’t devolve power to individuals alone, because it doesn't work – they are too far form decision-making to use it, as the free schools are liable to find out. You need intermediary institutions, as numerous and as local as possible. You also need powerful, ambitious and democratic local government. The Conservative Party has still not learned that lesson and the vital importance of local institutions whether they are local banks or local hospitals.

The other point is that Mrs Thatcher never learned about the grammar of change. When you make things happen, you can often create an equal force in the other direction. This is how William Morris put it:

"Men fight and lose the battle, and what they the thing that they thought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and then turns out to be not what they wanted and has to be fought for again under another name.”

That is how things actually work and Margaret Thatcher never grasped it. That is why Scottish devolution, for example, is part of her unexpected legacy.

So was she really an Anglo-Saxon? Or was she actually a Bonaparte figure, a giant of Bismarckian dimensions, with an iron grip, dressed in the garb of King Alfred?

Published on April 10, 2013 00:44

April 9, 2013

The peculiar irony of Thatcherism

The death of Margaret Thatcher makes me feel rather elderly. Her spirit seems to have presided over British politics, in one way or another, since I joined a political party (May 1979 as it happens). She was 54 when she became Prime Minister, which is what I am now. Scary thought.

Her death will I expect be a signal for a huge amount of rubbish talked on both sides of the conventional political divide.

The main issue which they agree on is that the moment when she mounted the steps of 10 Downing Street, with St Francis’ poem scribbled on a bit of paper, changed the UK for good.

The main issue which they agree on is that the moment when she mounted the steps of 10 Downing Street, with St Francis’ poem scribbled on a bit of paper, changed the UK for good.

I don’t think so.

Yes, she provided an image of resolution despite the turmoil around her – the damage caused to British industry by our very own petro-currency, the bombs and strikes. But she could afford to: unlike the prime ministers before her and after her, she had a working majority to bolster her rhetoric – an inoculation against compromise.

That is the fantasy of the right. The fantasy of the left is that she ushered in a period of unprecedented selfishness and individualism. Nobody who remembers life under the Callaghan government before hers could possibly believe this.

It is true that her government presided over Big Bang, but that was more about the entry of American investment banks into London, seeking whom they would devour. Yes, it is true, it was also facilitated.

There was a change, but it didn’t come in May 1979 when she took over. It took place in October 1979 when a small group of radicals around Geoffrey Howe and Nigel :Lawson ended currency exchange controls.

After that everything changed: government room for manoeuvre and creative innovation was hobbled, and now $4 trillion changes hands every day, most of it speculative. It was a huge shift; it was not debated by the cabinet (they were informed as the shift happened). Thatcherism followed – but, before they consulted her a few weeks before, the conspirators had been unsure whether she would agree or not.

The truth was that Margaret Thatcher was not originally a Thatcherite. She was a firm supporter of home owners and the middle classes, and she had Thatcherism thrust upon her by the very surprising success of the end of exchange controls. Yes she grew into the role, but it didn't end as she originally intended.

And here is the ultimate irony, and I have told the full story in my new book Broke . The end of exchange controls led to the end of the so-called Corset, which limited the amount of money that went into mortgages. An explosion of finance followed. Nothing replaced it.

The housing market was allowed to let rip, leading to unsustainable house price rises. Thatcherism, which was based on the idea of a property-owning democracy, has led directly to the situation where home ownership in the UK is lower than Bulgaria or Romania – and rents have rocketed as a result.

In short, we now live in a city (those of us who live in London) where only the ultra-rich, ushered in by a mismanaged Big Bang, can afford to get on the housing ladder. The rest of us, certainly in London and the south east, have to choose between indentured semi-servitude to our mortgage provider or to our landlord.

Ironic or what.

Her death will I expect be a signal for a huge amount of rubbish talked on both sides of the conventional political divide.

The main issue which they agree on is that the moment when she mounted the steps of 10 Downing Street, with St Francis’ poem scribbled on a bit of paper, changed the UK for good.

The main issue which they agree on is that the moment when she mounted the steps of 10 Downing Street, with St Francis’ poem scribbled on a bit of paper, changed the UK for good. I don’t think so.

Yes, she provided an image of resolution despite the turmoil around her – the damage caused to British industry by our very own petro-currency, the bombs and strikes. But she could afford to: unlike the prime ministers before her and after her, she had a working majority to bolster her rhetoric – an inoculation against compromise.

That is the fantasy of the right. The fantasy of the left is that she ushered in a period of unprecedented selfishness and individualism. Nobody who remembers life under the Callaghan government before hers could possibly believe this.

It is true that her government presided over Big Bang, but that was more about the entry of American investment banks into London, seeking whom they would devour. Yes, it is true, it was also facilitated.

There was a change, but it didn’t come in May 1979 when she took over. It took place in October 1979 when a small group of radicals around Geoffrey Howe and Nigel :Lawson ended currency exchange controls.

After that everything changed: government room for manoeuvre and creative innovation was hobbled, and now $4 trillion changes hands every day, most of it speculative. It was a huge shift; it was not debated by the cabinet (they were informed as the shift happened). Thatcherism followed – but, before they consulted her a few weeks before, the conspirators had been unsure whether she would agree or not.

The truth was that Margaret Thatcher was not originally a Thatcherite. She was a firm supporter of home owners and the middle classes, and she had Thatcherism thrust upon her by the very surprising success of the end of exchange controls. Yes she grew into the role, but it didn't end as she originally intended.

And here is the ultimate irony, and I have told the full story in my new book Broke . The end of exchange controls led to the end of the so-called Corset, which limited the amount of money that went into mortgages. An explosion of finance followed. Nothing replaced it.

The housing market was allowed to let rip, leading to unsustainable house price rises. Thatcherism, which was based on the idea of a property-owning democracy, has led directly to the situation where home ownership in the UK is lower than Bulgaria or Romania – and rents have rocketed as a result.

In short, we now live in a city (those of us who live in London) where only the ultra-rich, ushered in by a mismanaged Big Bang, can afford to get on the housing ladder. The rest of us, certainly in London and the south east, have to choose between indentured semi-servitude to our mortgage provider or to our landlord.

Ironic or what.

Published on April 09, 2013 00:42

April 8, 2013

Why green civil disobedience will rise again

There is an argument brought to bear on the green movement by business groups and so-called ‘free market’ think-tanks that wealth and the environment go hand in hand.

There is an argument brought to bear on the green movement by business groups and so-called ‘free market’ think-tanks that wealth and the environment go hand in hand.It is quite true that conventional growth goes up. So do environmental standards. The argument is used to assert that going for growth will paradoxically achieve all the objectives that the green campaigners want – less pollution, breathable air, happy bees, and so on.

You have to take this seriously. Poor places can’t afford to tackle the very pollution that makes them so poor.

There is also an edge to the argument which is absolutely intentional. It implies that environmental concerns are somehow secondary , the playful and pathetic byways of the affluent and bourgeois.

I say 'so-called' free market think-tanks because they do not espouse the free market that I recognise. Both the CBI and the once fearsome Institute for Economic Affairs seem to me to have become apologists for monopoly. But that's another story.

I mention all this partly because I was staggered that the UK government allowed the ban on bee-killing pesticides to fail in the European Union, and partly because there is a paradoxical flaw in the argument.

It forgets what the process is whereby pollution is vanquished and environmental standards rise. It assumes that we all need to relax, get rich and the world will get greener all by itself.

It won't. Because people have to fight for it.

Bit by bit, step by step, civil society demands it – just as the people of Beijing are demanding pollution statistics, just as Hazel Henderson in New York City demanded and achieved the same thing a generation ago.

There is no green space, no pollution controls, no assertion of the long-term over the short-term, that has not been fought for.

And the connection with rising incomes is very simple. It provides people with the space in their lives and the political power with which to fight, in a way that the precariat – monitored every minute by their employers – never can.

That is why the middle classes, or middle incomes in particular, are absolutely vital for green progress. If we are all reduced to proletarian standards (see my forthcoming book Broke ), nobody can fight.

So it is true that rising incomes leads to environmental improvement, but it is not good enough for the powerful to tell us to stop complaining – it isn't enough to say: let’s build more runways, forget the bees or live with the health effects of fracking, because wealth is good for the environment.

It is good for the environment because it allows people to fight for it.

My political antennae, which are not very sharp, suggest that we are entering a period when this is going to be very important – when people begin to mind very much indeed about fracking and nuclear energy.

Not because of political or economic theory, or even because the green movement exhorts them to. It will be because they are afraid they are ill because of them, and their children are getting ill because of them. So strap in for a bumpy ride, starting around 2015.

Published on April 08, 2013 02:48

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.