David Boyle's Blog, page 85

April 7, 2013

Meaning at work and why we lost it

It was Hilary Clinton who first coined the phrase 'the politics of meaning'. I wrote about that in the collection of essays called

Reinventing the State

, which had rather a good picture of Chris Huhne on the front, and argued that Liberals should avoid positioning themselves as a wholly secular philosophy.

I must admit that the essay had nothing whatever to do with reinventing the state, so the editors were very generous in overlooking this and publishing it anyway.

What I wanted to say was that, although many people who are attracted to Liberal politics are not religious, many are also searching for some kind of spiritual understanding. In the USA, it is widely argued that the Democrats made a mistake by aligning themselves wholly with secular modernity, and driving those who are sceptical about it into the arms of the so-called ‘theo-cons’.

The figures for those who still struggle with spirituality in the UK (about three quarters), rather than just those who go regularly to church, suggest that these ‘theo-cons’ are exploiting a real human need which progressives dismiss at their peril. It is a need that many, both rich and poor, face at some point in their lives, and described in the United States by Rabbi Michael Lerner as a ‘crisis of meaning’.

They want their lives to be about more than just money and material security. They search for a language in which to express this politically, finding it often in green campaigns or similar. Yet the more they search for that language in politics, the more the progressive forces concentrate on material security and suppress anything remotely spiritual, for fear that it is some kind of conservatism in disguise.

‘It is imperative that liberal and progressive forces develop an understanding of this spiritual crisis, and a progressive politics of Meaning to counter the right-wing politics of Meaning,’ wrote Lerner. That is a North American interpretation, but it is relevant here too.

I thought of all this again during the 2011 riots. Heavens, I even wrote about the riots and meaning. And then again when I got a fascinating essay through from the management consultants McKinsey about increasing what they called the 'Meaning Quotient' at work.

The article is by Susie Cranston and Scott Keller and suggests we should think of MQ alongside IQ and EQ as a key factor in success, except of course that MQ is a kind of group measure. They are absolutely right that MQ requires employees to be given responsibility and a sense of excitement and purpose, but hazy about how it can be achieved.

This is fascinating and ironic too, given that McKinsey has been so corrosive of MQ in so many public services, with their advocacy of iron control, spurious measurement and ever more controlling IT systems. Their central maxim - 'everything can be measured and what can be measured can be managed' - is such a dangerous fallacy exactly because it corrodes meaning at work.

The descriptions of the latest equipment in Amazon's warehouses earlier this year reveal what are in effect Meaning Free Zones, where they measure everyone even in the toilet, and discourage conversation. Whether McKinsey were the main instigators of this working style or not, this is the direction that management is going in the world and it is a recipe for ineffectiveness - for all the reasons that Cranston and Keller suggest.

Perhaps this means a major change of direction by McKinsey. I hope so, but I suspect they remain as Taylorist as ever when it comes to dealing with minions - and we are going to have to wreak this revolution ourselves. If we want our services to be effective and cost-effective.

I must admit that the essay had nothing whatever to do with reinventing the state, so the editors were very generous in overlooking this and publishing it anyway.

What I wanted to say was that, although many people who are attracted to Liberal politics are not religious, many are also searching for some kind of spiritual understanding. In the USA, it is widely argued that the Democrats made a mistake by aligning themselves wholly with secular modernity, and driving those who are sceptical about it into the arms of the so-called ‘theo-cons’.

The figures for those who still struggle with spirituality in the UK (about three quarters), rather than just those who go regularly to church, suggest that these ‘theo-cons’ are exploiting a real human need which progressives dismiss at their peril. It is a need that many, both rich and poor, face at some point in their lives, and described in the United States by Rabbi Michael Lerner as a ‘crisis of meaning’.

They want their lives to be about more than just money and material security. They search for a language in which to express this politically, finding it often in green campaigns or similar. Yet the more they search for that language in politics, the more the progressive forces concentrate on material security and suppress anything remotely spiritual, for fear that it is some kind of conservatism in disguise.

‘It is imperative that liberal and progressive forces develop an understanding of this spiritual crisis, and a progressive politics of Meaning to counter the right-wing politics of Meaning,’ wrote Lerner. That is a North American interpretation, but it is relevant here too.

I thought of all this again during the 2011 riots. Heavens, I even wrote about the riots and meaning. And then again when I got a fascinating essay through from the management consultants McKinsey about increasing what they called the 'Meaning Quotient' at work.

The article is by Susie Cranston and Scott Keller and suggests we should think of MQ alongside IQ and EQ as a key factor in success, except of course that MQ is a kind of group measure. They are absolutely right that MQ requires employees to be given responsibility and a sense of excitement and purpose, but hazy about how it can be achieved.

This is fascinating and ironic too, given that McKinsey has been so corrosive of MQ in so many public services, with their advocacy of iron control, spurious measurement and ever more controlling IT systems. Their central maxim - 'everything can be measured and what can be measured can be managed' - is such a dangerous fallacy exactly because it corrodes meaning at work.

The descriptions of the latest equipment in Amazon's warehouses earlier this year reveal what are in effect Meaning Free Zones, where they measure everyone even in the toilet, and discourage conversation. Whether McKinsey were the main instigators of this working style or not, this is the direction that management is going in the world and it is a recipe for ineffectiveness - for all the reasons that Cranston and Keller suggest.

Perhaps this means a major change of direction by McKinsey. I hope so, but I suspect they remain as Taylorist as ever when it comes to dealing with minions - and we are going to have to wreak this revolution ourselves. If we want our services to be effective and cost-effective.

Published on April 07, 2013 00:39

April 6, 2013

When hospitals start gaming with patients

When he encouraged Leeds General Hospital to stop heart operations on children a week ago, the NHS medical director said there were three aspects of their work that worried him. One of these was their failure - which the hospital disputes - to refer complex cases elsewhere.

When he encouraged Leeds General Hospital to stop heart operations on children a week ago, the NHS medical director said there were three aspects of their work that worried him. One of these was their failure - which the hospital disputes - to refer complex cases elsewhere.At the heart of this is one of the great conundrums of the new NHS. In my choice review, I put it like this:

"There are certainly ways in which a narrow interpretation of choice can make choice meaningless in practice."

The problem is that, for very good reasons, responsibility for meeting budgets has been devolved to NHS units. That is as it should be. But what happens when the managers start interpreting that responsibility so literally that they begin to maximise income at the expense of their patients - when competition starts to corrode the good of the people the NHS is supposed to benefit?

Hospitals make more money when patients are referred direct from GPs than they do when they are referred from inside. So it is hardly surprising that, sometimes, patients are sent back to their GP for the next referral - when it could have all be sorted there and then.

There are even managers who discourage their hospital doctors from talking to GPs. Sometimes they have been known to forbid them, in case it means that a patient is not referred because of the conversation. Leeds is one of the places where doctors across the city have created their own informal communications mechanisms to make sure this doesn't happen.

Sarah's aunt had been referred to a heart recovery nurse who never followed up as promised. To get back onto the programme, she has to go back to the GP and be referred again to the cardiologist, and thence to the nurse specialist. The hospital will earn money from all these unnecessary appointments - what John Seddon calls 'failure demand' - but the resources of the NHS as a whole are stretched further.

This kind of gaming is happening around the NHS, even if it doesn't happen most of the time. There are already rules that are designed to prevent hospitals from wasting patients’ time in order to earn extra revenue, especially as this also clutters up the system unnecessarily. There are target ratios for follow-up appointments that are intended to prevent abuse, but in the end targets are probably too blunt an instrument to be effective.

Patients need to have basic rights which they can appeal to. Some kinds of behaviour may also need to be ruled out by NHS regulators or under the NHS constitution. Free communication between doctors and patients, and between professionals, needs to be absolutely guaranteed.

Personally, I think Monitor should define as 'anti-competitive' any behaviour which unnecessarily takes up capacity or wastes valuable time for patients, or wastes resources in the system as a whole.

We await the verdict about Leeds and their heart operations. But clearly one of the charges against them - which, as I said, they deny - is that they clung to complex cases because of the earnings, when they should have been referred elsewhere.

That is the question at the heart of all this - it is about a narrow and intense kind of competition paradoxically compromises the real needs of patients. In the end, it probably needs to come from the patients themselves. Give them more power, I say...

The NHS is never going to allow the terrors of total competition. Nor is it ever, it seems to me, going to relax the budgetary pressures on individual trusts. That means some kind of accommodation between these contradictory forces is needed in practice.

The problem is - where is the pressure to make sure these contradictions are resolved in favour of individual patients?

Published on April 06, 2013 02:45

April 5, 2013

Despite the survey, I'm middle class - really

There is suddenly a great deal of interest in class, following publicity about the new online class survey, which suggests that the traditional class demarcations (upper, middle, working) should give way to seven - from the elite to the precariat.

There is suddenly a great deal of interest in class, following publicity about the new online class survey, which suggests that the traditional class demarcations (upper, middle, working) should give way to seven - from the elite to the precariat.I'm not sure about this. I did the survey myself and discovered that I am 'traditional working class'. This really isn't the case: I could imagine being in the precariat - I am self-employed - but traditional working class, no. I might like to be, but I'm not.

The odd thing was that my father did the same survey and it came to the same conclusion about him. I suspect that the survey has two big problems:

1. It puts far too much emphasis on income.

2. It takes no account of upbringing.

I was definitely brought up as middle class, including dancing classes and piano classes, not to mention private school and Oxford. I may not earn much, but one of the traditional characteristics of the middle classes is supposed to be their ability to defer gratification. I admit, I have deferred it indefinitely to be a writer, but I am still middle class...

Professor Mike Savage, the acknowledged national authority on class, was involved in the survey, but I think his previous nomenclature - professional, intermediate, working - and based largely on culture, is a more accurate portrayal. His original BBC survey was based on classifications which divided people according to what aspects of culture they enjoyed, into professional classes (hardly ever watch TV), the intermediate class (which would be the professional class except that it shares a much lower life expectancy with the working classes), and the working class (watches four times as much TV as the professional class, but never goes to musicals).

This nomenclature slightly muddies the water, because 29 per cent of all three classes still go to the pub once a week. But yes it does omit the emergence of the new class, the international One Per Cent that is hoovering up the money from the middle classes, and here is the main point.

For one thing, the new classification 'elite' doesn't capture this. For one thing, those earning over £100,000 are actually far less than one per cent. These are not a class, they are a throwback to the old aristocratic privileges for a tiny minority who push up the prices for the rest of us.

For another thing, the impact this has on the middle classes seems to have passed the survey by. It means that, perhaps more than any other time in their history, the middle classes are struggling to get by - from those on higher than average earnings right down to the public sector middle classes, running big nursery schools on £17,000 a year.

Does that make them 'traditional working class'? I don't think so. It just makes them struggling middle class.

It so happens that my new book about the middle classes, and whether they can survive another generation - the chances are against, I fear - is coming out in three weeks time (picture above). The full truth will then be revealed...

Published on April 05, 2013 01:42

April 4, 2013

The IT recipe for failure

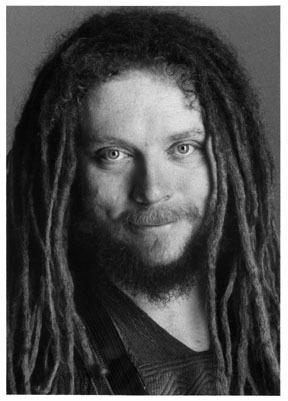

Jaron Lanier is one of my heroes. He has dreadlocks, is an accomplished digital musician and pioneer of virtual reality, and his book You Are Not a Gadget describes the development of what he calls digital Maoism, where web users become a new proletariat toiling for the benefit of an all-powerful virtual bourgeoisie. “We're sending them to peasanthood, very much like the Maoists have,” he wrote.

Jaron Lanier is one of my heroes. He has dreadlocks, is an accomplished digital musician and pioneer of virtual reality, and his book You Are Not a Gadget describes the development of what he calls digital Maoism, where web users become a new proletariat toiling for the benefit of an all-powerful virtual bourgeoisie. “We're sending them to peasanthood, very much like the Maoists have,” he wrote.Lanier’s target has been the idea that individual creativity is being undermined by the internet, partly because so few people seem prepared to pay for it – I speak as a writer – and partly because the prophets of a digital future are toiling towards a day when there will be no individual books, pictures or musical compositions; just one ‘mashed’ whole.

That was the idea behind Kevin Kelly’s predictions in the New York Times in 2006, and it is the meaning behind the innovations known as Web 2.0.

Now he has gone further and has written a closely argued diatribe about the design flaws in the current internet regime that allows a few monopolists to impoverish us.

More about this, and related issues, in my book The Human Element. I mention this rather belatedly because of the book review by Bryan Appleyard, who I revere for his lonely campaign in favour of the human spirit against scientism and reductionism. Because Lanier's new book takes the argument further, explaining how a handful of monopolistic internet giants are hollowing out the economy by stealing tiny bits of information that are rightfully owned by us.

Appleyard reviews Lanier along with Evgeny Morozov and his furious diatribe To Save Everything, Click Here.

What really scares me about the way IT is used is that its proponents believe it can replace human skills as well as machine skills. There are those who believe that it can take over teaching from human beings, just as there are those who are working towards using IT for most medical functions. There are even those who believe that virtual sex will be better than real sex, eventually.

The sad thing is not just that these people are wrong - that they have not understood the functions best delivered by machine and those that require some kind of human relationship to make them work. The really sad thing is that so much attention, so much investment money, so much licence to re-think the world, is going their way.

It is a recipe for ineffectiveness. Anyone who believes the most effective way of educating children is to plug them into an alogorithm will discover this very quickly. Unfortunately, many of the world's movers and shakers really do.

Published on April 04, 2013 08:00

April 3, 2013

Gove, Google and Gradgrind

Michael Gove has had rather a battering over Easter, mainly thanks to the impassioned speeches at the National Union of Teachers conference. I don't share their rage at his curriculum changes.

Michael Gove has had rather a battering over Easter, mainly thanks to the impassioned speeches at the National Union of Teachers conference. I don't share their rage at his curriculum changes.Speech after speech by a series of teachers covered most of the news broadcasts - little else was happening except for various Easter messages - and you couldn't fault the logic. Nobody wants a return to Victorian rote-learning. Nobody wants a Gradgrindian regress to the idea that "facts alone are wanted". In fact, it was the prospect of escaping the Gradgrindian direction of New Labour's education that made me quite pleased to get a radical like Gove.

But what is equally impossible is that the fire of education can be lit without content. That you can teach thinking and arguing without context or facts. That you can abandon the real world completely, because children can look up what they need on Google.

Just as a dull recitation of facts is soul-destroying, so is schooling with no facts at all - all technique and logic and systems. It is education without the real world. It is just as dead as factual recitation. Deader in fact.

So we might argue about Gove's approach to the chronology of history. I might choose different dates, but at least he has a chronology. At least there is a heart to his history curriculum, rather than an endless miserable return to the Second World War.

At least there is a history curriculum. One of the hallmarks of regressive utilitarianism, and the last government must have been the most utilitarian since they stuffed Jeremy Bentham, is a horror of history.

So I don't agree with everything Michael Gove is doing, but on this I am absolutely on his side.

Sarah told me a fascinating story about the reliance on internet search engines in the classroom from when she was a teaching assistant.

"If God made the world, then who made God?" asked one child. It is the kind of question that children find endlessly fascinating.

The teacher was flummoxed and apparently unequipped to use this as the basis for the kind of discussion that education ought to be about.

"Good question," she said. "Why don't you look up the answer on Ask Jeeves."

Published on April 03, 2013 00:45

April 2, 2013

Still sceptical about Richard III

Well, I don’t know. I watched the recent documentary Richard III: The Unseen Story about the discovery of the bones of Richard III again over Easter – watched it through twice in fact. And I’m still not quite convinced.

I admit, I am partly defending my own impression of Richard III, based on somewhat dubious eye-witness accounts, that he was not actually a hunchback at all. The programme revealed that his spine did not begin to bend until he was in his teens, so perhaps that is still consistent with the stories.

Even so, it was all just too perfect. The first bones found in the first trench. And whoever it was turned out to have curvature of the spine. There is an air of a story so perfect that it just had to be true about this.

There is something faintly reminiscent of the Piltdown Man, the 1912 hoax that fooled everyone that the missing link had been discovered in Sussex. It just had to be true – but it wasn’t.

The analysis and DNA tests were all convincing of course. I just point out the following:

The carbon dating test had to be tweaked by dietary considerations to fit the right period. The DNA test was actually of mitochondrial DNA so, far from being an exact match, it would have been matched by two people in a hundred. By probability, everyone in the country is descended from Edward III, Richard III's great-great grandfather through both parents.Given these remaining doubts in my mind that this was actually Richard III, I wanted to know more about the role of the Richard III Society in the discovery – their purposes and personnel, their ability to be so precise about the site, their search for a relative down the female line for a DNA test (back in 2005).

I’m not disputing what they believe. I am pretty sure in my own mind, having read David Baldwin's book, that the Princes in the Tower survived their uncle’s ministrations – that Edward V died of flu and Richard of York disappeared and eventually became a bricklayer in Kent (see, I am credulous in my own way). Richard Plantagenet's tomb can still be seen in a derelict church on the Pilgrim's Way at Eastwell in Kent. I just want to know the back story about the dig, how it was funded, how it came about.

Call me old-fashioned. Call me an old curmudgeon. I have no doubts about the absolute integrity of everyone involved. I just wonder about the ability of very clever people to delude themselves when the very first bones the digger uncovered turned out to have a curved back.

These questions were not answered. Heavens, they weren’t even asked – and perhaps not surprisingly given that the Society was one of the producers of the documentary.

Published on April 02, 2013 09:44

April 1, 2013

Come back Co-op Bank, all is forgiven

A few weeks ago, I had an online rant at the expense of Co-op Bank. I had a very polite and helpful reply from them afterwards - a series of them actually - and it is now time to set the record straight on one or two things.

First, there is no way they use the insidious American-style high-to-low transaction re-ordering software, I'm glad to say. They tot up our balances at the end of every day and charge accordingly. There is no manipulation of the order in which we carry out our transactions, as some banks do. So thank goodness for that.

Second, their ethical policy does apply to investments carried out with other companies. They apply a basic ethical screen, to screen out investment in tobacco, arms and nuclear energy, and then apply their ethical engagement policy. This is what they say:

"It may be useful to outline the Co-operative Investments Ethical Engagement Policy (EEP), which covers insurance and investment products. The EEP was launched in 2005 following extensive customer consultations and over 45,000 customer replies. It covers 8 areas of customer concern including human rights, animal welfare and environmental sustainability and we report every year on how we’ve been doing in our Sustainability Report which you can find on the internet at:

www.co-operative.coop/corporate/sustainability/

"Our investment products generally invest across the entire range of market sectors and indeed we are required to do so by the Financial Services Authority in order to spread financial risk. The Ethical Engagement Policy then gives us the mandate to use our position as a major investor to engage companies on a commercial level to discuss issues of concern. In this way we can challenge major businesses from the inside, to improve their performance in relation to issues such as human rights, environmental sustainability and corporate governance, for example, and all our unit trusts benefit from our engagement insight."

As I said in my original rant, the reason I stick with Co-op and will continue to do so, is that they have a human call centre, with real human beings at the end of the line, and based somewhere in particular. That really is important, and very rare.

The other two things I complained about remain a problem. Why should I be charged £20 to 'renew' an overdraft I haven't asked to cancel? Why should I be sent endless bank statements with just a few items on?

Both of those are irritating, but they are not exactly deal-breakers. Sorry I suggested otherwise...

First, there is no way they use the insidious American-style high-to-low transaction re-ordering software, I'm glad to say. They tot up our balances at the end of every day and charge accordingly. There is no manipulation of the order in which we carry out our transactions, as some banks do. So thank goodness for that.

Second, their ethical policy does apply to investments carried out with other companies. They apply a basic ethical screen, to screen out investment in tobacco, arms and nuclear energy, and then apply their ethical engagement policy. This is what they say:

"It may be useful to outline the Co-operative Investments Ethical Engagement Policy (EEP), which covers insurance and investment products. The EEP was launched in 2005 following extensive customer consultations and over 45,000 customer replies. It covers 8 areas of customer concern including human rights, animal welfare and environmental sustainability and we report every year on how we’ve been doing in our Sustainability Report which you can find on the internet at:

www.co-operative.coop/corporate/sustainability/

"Our investment products generally invest across the entire range of market sectors and indeed we are required to do so by the Financial Services Authority in order to spread financial risk. The Ethical Engagement Policy then gives us the mandate to use our position as a major investor to engage companies on a commercial level to discuss issues of concern. In this way we can challenge major businesses from the inside, to improve their performance in relation to issues such as human rights, environmental sustainability and corporate governance, for example, and all our unit trusts benefit from our engagement insight."

As I said in my original rant, the reason I stick with Co-op and will continue to do so, is that they have a human call centre, with real human beings at the end of the line, and based somewhere in particular. That really is important, and very rare.

The other two things I complained about remain a problem. Why should I be charged £20 to 'renew' an overdraft I haven't asked to cancel? Why should I be sent endless bank statements with just a few items on?

Both of those are irritating, but they are not exactly deal-breakers. Sorry I suggested otherwise...

Published on April 01, 2013 03:39

March 31, 2013

Carey is blind to the real 'aggressive secularism'

As a member of the Church of England, I am occasionally irritated by our erstwhile archbishop George Carey. Occasionally more than irritated, but - since it is Easter - I am choosing words carefully.

There may indeed be problems in our society about what he calls 'aggressive secularism', but it has little to do with David Cameron's plans for gay marriage.

In fact, statements like that - timed for Easter by the Daily Mail - simply plays into the hands of those in the media and the church who seem to think the central Christian message is some kind of warning against homosexuality.

How many times, incidentally, do you think Jesus mentions homosexuality in the gospel accounts? The answer is not at all.

Some kinds of secularism are important. We should not be ramming specific religions down the throats of people for whom they are unwelcome (as if we were). Equally, we should not be insisting on secular culture for everyone in every situation, especially when 'secular culture' is interpreted as a narrow, puritanical positivism.

So my irritation with Carey is that he seems to be blind to the real problem, which includes:

The way political parties encourage a miserably empty consumerism, and assume this sums up people's highest aspirations. See my blog on the 2011 riots. One result of this kind of perverse morality is the way we allow big banks to do almost whatever they like because they pay so much in tax.The way every high ideal, at work and in social policy and every hope beyond, is assumed to be measurable, and reducable to some kind of digital delivery system. See my blog about measurement.The way a small group of extreme positivists pour public scorn on anything that cannot be seen under a microscope, whether it is complementary health or God.All these reduce our common life, narrow our aspirations, fetter our imaginations and provide what for me are the real symptoms of aggressive secularism. So why does Carey obsess about the way some people express their love for each other? That reductionism is a symptom of the very secularism he warns against.

We have managed to shake off the most miserably utilitarian government in history (I refer to New Labour). We haven't really struggled out the other side yet. I don't suppose we ever will if people continue to imagine that the profundities of religion - whatever you might think of them - can be reduced to your attitude to same-sex relationships.

There may indeed be problems in our society about what he calls 'aggressive secularism', but it has little to do with David Cameron's plans for gay marriage.

In fact, statements like that - timed for Easter by the Daily Mail - simply plays into the hands of those in the media and the church who seem to think the central Christian message is some kind of warning against homosexuality.

How many times, incidentally, do you think Jesus mentions homosexuality in the gospel accounts? The answer is not at all.

Some kinds of secularism are important. We should not be ramming specific religions down the throats of people for whom they are unwelcome (as if we were). Equally, we should not be insisting on secular culture for everyone in every situation, especially when 'secular culture' is interpreted as a narrow, puritanical positivism.

So my irritation with Carey is that he seems to be blind to the real problem, which includes:

The way political parties encourage a miserably empty consumerism, and assume this sums up people's highest aspirations. See my blog on the 2011 riots. One result of this kind of perverse morality is the way we allow big banks to do almost whatever they like because they pay so much in tax.The way every high ideal, at work and in social policy and every hope beyond, is assumed to be measurable, and reducable to some kind of digital delivery system. See my blog about measurement.The way a small group of extreme positivists pour public scorn on anything that cannot be seen under a microscope, whether it is complementary health or God.All these reduce our common life, narrow our aspirations, fetter our imaginations and provide what for me are the real symptoms of aggressive secularism. So why does Carey obsess about the way some people express their love for each other? That reductionism is a symptom of the very secularism he warns against.

We have managed to shake off the most miserably utilitarian government in history (I refer to New Labour). We haven't really struggled out the other side yet. I don't suppose we ever will if people continue to imagine that the profundities of religion - whatever you might think of them - can be reduced to your attitude to same-sex relationships.

Published on March 31, 2013 10:54

March 30, 2013

Lots of data, nobody listening

A few years ago, the Environment Agency asked me to write about the year 2020, which I did - and with my tongue slightly in my cheek. This is the future as I painted it, and the Daily Mail even drew a picture of it (but I can't find the link).

A few years ago, the Environment Agency asked me to write about the year 2020, which I did - and with my tongue slightly in my cheek. This is the future as I painted it, and the Daily Mail even drew a picture of it (but I can't find the link).I had been fascinated, and slightly horrified, by the development of Matsushita's digital toilet and could just imagine what it would mean in practice, so I began the article like this:

It is 30 October 2020. The alarm clock bleeps at 7am in the Dumill household, as the light seeps into the sky above the new village of Hamstreet in Kent. The cock crows a few streets away in one of the small-holdings of one of the part-time farmers. He washes his face and the water whirls down the plug-hole. In the distance, he can hear the hum of the household water purification plant starting its work for the day. He flushes the toilet, which automatically analyses his sample. Richard's cholesterol level is slightly high, after a heavy dinner of chips and farmed cod, and the toilet sends the information digitally to his doctor's surgery computer, which ignores it completely...

Dumill and Hamstreet, incidentally, were an echo of the characters and places invented by the geographer Peter Hall in his planning classic London 2000.

I thought of all this when I heard a discussion on Friday about the Leeds General Infirmary's heart unit, when one of the interviewees came up with this extremely important statement:

"Although data was being collected, nobody was looking at it..."

And there is the Achilles Heel of the digital measurement revolution. Yes, there is measurement. Yes, there is data. But there isn't anyone looking at the data and - if there is - there isn't anyone available to do anything about the problems that emerged.

Yes, we can track lonely old people around their flats, and check their blood pressure remotely. What we don't seem to be able to do is to work out how we can get people round to make sure they are OK - or, heavens, even maybe talk to them.

So we are deluged by more and more data, but less and less information. Still less, as T. S. Eliot put it, knowledge or wisdom.

This is a subject - too much measurement - that I began writing about in The Tyranny of Numbers , and there is a lot more to say about it.

And the centre of this whole problem is the Care Quality Commission, awash with data - much of it still coming over the fax machine, which is some explanation of their dysfunctionality - yet so few actual insights, because they require human intervention, imagination, insight. Because our resources going into social innovation are so small compared to what goes into technological innovation.

You can't measure your way to that.

The idea that government or public services can somehow just run themselves just on data, without human intervention, is a terrifying utilitarian fantasy which infected the Blair government and explains the breadth of their failure.

Published on March 30, 2013 03:22

March 29, 2013

Lamp-posts and the terrible costs of centralisation

During the hottest week of May (remember those?) a few years back the month, my mother-in-law arrived at the council-run college in Croydon where she taught part-time, to find that the central heating was on.

It was particularly sticky and sweltering. During every spare moment, she set about the long business of tracking down somebody who had sufficient authority to turn off the radiators. My mother-in-law is one of those people who can make things happen, very gently but determinedly, but – even for her – getting the radiators turned off in the sweltering heat was no easy project.

It was particularly sticky and sweltering. During every spare moment, she set about the long business of tracking down somebody who had sufficient authority to turn off the radiators. My mother-in-law is one of those people who can make things happen, very gently but determinedly, but – even for her – getting the radiators turned off in the sweltering heat was no easy project.

The principal of the college wasn’t responsible. Nor were those responsible for the college at the local authority. Most of them not only had no power over their own heating; they also had no idea who had – a familiar experience in centralised public services.

Towards the end of the day, she discovered the right person. It was a man with a laptop, somewhere in the council building which also housed the education officers. He was persuaded to act, and – at the click of a mouse – the radiators went off.

In those heady first few years after the Berlin Wall came down, I used to write a regular newsletter on renewable energy, and often included anecdotes about the energy use in the great Soviet-style apartment buildings on the outskirts of Moscow or Budapest – pumping heat into the surrounding atmosphere whether it was hot or cold.

We used to laugh at this, amazed that nobody could turn off their ancient totalitarian radiators. Yet we seem to be in a similar situation in the UK – my wife was teaching in a local school where the radiators were also blazing out during the hottest days, so I don’t believe this is actually very unusual. The reason is the same; the institutions are too big for the human dimension to work.

Centralisation is expensive because it provides for no initiative, no responsibility, no intelligent feedback. Find out more in my book The Human Element.

Which brings me to the reason for the photo, which is of the street outside my house. A few weeks ago I blogged about the bizarre picture of Croydon Council planting a whole series of new lamp-posts during a recession when they are busily closing libraries - and the new lamp-posts do not even generate their own solar energy, so they will have to be replaced pretty soon.

Now we have the new lamp-posts, under a massive contract with Skanska which also covers next-door Lewisham and lasts for five years. But we also have the old ones. The picture above is the only spot in our street where the two lamp-posts, old and new, are not blazing forth next to each other. All the other new lamp-posts are blazing right next to the old ones, which are also blazing.

Does this kind of inefficiency matter? The answer is, across two whole London boroughs, it does. Because, as I may have mentioned before, small plus small plus small equals big.

The principal of the college wasn’t responsible. Nor were those responsible for the college at the local authority. Most of them not only had no power over their own heating; they also had no idea who had – a familiar experience in centralised public services.

Towards the end of the day, she discovered the right person. It was a man with a laptop, somewhere in the council building which also housed the education officers. He was persuaded to act, and – at the click of a mouse – the radiators went off.

In those heady first few years after the Berlin Wall came down, I used to write a regular newsletter on renewable energy, and often included anecdotes about the energy use in the great Soviet-style apartment buildings on the outskirts of Moscow or Budapest – pumping heat into the surrounding atmosphere whether it was hot or cold.

We used to laugh at this, amazed that nobody could turn off their ancient totalitarian radiators. Yet we seem to be in a similar situation in the UK – my wife was teaching in a local school where the radiators were also blazing out during the hottest days, so I don’t believe this is actually very unusual. The reason is the same; the institutions are too big for the human dimension to work.

Centralisation is expensive because it provides for no initiative, no responsibility, no intelligent feedback. Find out more in my book The Human Element.

Which brings me to the reason for the photo, which is of the street outside my house. A few weeks ago I blogged about the bizarre picture of Croydon Council planting a whole series of new lamp-posts during a recession when they are busily closing libraries - and the new lamp-posts do not even generate their own solar energy, so they will have to be replaced pretty soon.

Now we have the new lamp-posts, under a massive contract with Skanska which also covers next-door Lewisham and lasts for five years. But we also have the old ones. The picture above is the only spot in our street where the two lamp-posts, old and new, are not blazing forth next to each other. All the other new lamp-posts are blazing right next to the old ones, which are also blazing.

Does this kind of inefficiency matter? The answer is, across two whole London boroughs, it does. Because, as I may have mentioned before, small plus small plus small equals big.

Published on March 29, 2013 05:38

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.