David Boyle's Blog, page 89

February 25, 2013

The next economic consensus but one

The Brazilian economist Roberto Unger was so incisive and clear in his radicalism in the Radio 4 programme Analysis tonight, warning the Left in Britain not to be "paladins of nostalgia" but to have some kind of vision of the future. The bizarre thing is that so few of the interviewees - even the Social Liberal Forum's David Hall-Matthews - really seemed to grasp what he was saying.

Part of the problem, I suppose, is the BBC's obsession with the minutiae of Labour Party policy, which is a side-effect of getting an IPPR apparachik to present the programme.

It is true that the idea of 'pre-distribution' has real intellectual depth, and could provide an antidote to a century's disastrous Fabianism, but will it? On the evidence of the programme, probably not. Policy for political parties is a frustrating and deeply conservative compromise, these days, trying to fit new ideas into old frameworks until they are barely new at all.

But the debate which really caught my imagination was the one about banks. We are moving towards a new debate, which never quite seems to take off in the UK, about their future - but which neither Labour nor Conservative seem quite able to run with.

The question is not how to bend the banks to the will of politicians, which never quite seems to work, versus the idea that they have done their penance and must be left alone. That is the old debate and it has got us precisely nowhere.

What Unger brings to this is the idea that we need a different kind of economic institution to make the economy work for us. That implies breaking up the existing banks, which have ceased to function effectively, and to create a whole range of different kinds of banks - with their roots and allegiance locally and regionally - to finance and profit from a new kind of local economy.

Our politicians don't yet see that this isn't some kind of moral argument - a side issue to the main struggle to bring growth the old-fashioned way. It is the central tenet of a new economic approach that is designed to bring economic well-being, and may be the only way of doing so.

There is lots of money around for lending. What we so desperately lack is the institutions capable of lending it.

Unfortunately, the UK left seem to be determined to be 'paladins of nostalgia' instead.

Published on February 25, 2013 13:42

February 23, 2013

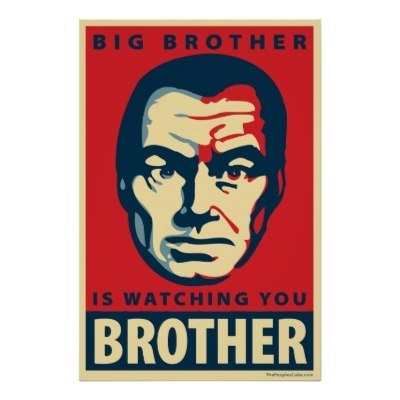

Amazon and Big Brother: the evidence mounts

There I was a week ago, drawing parallels between the way Amazon organises its warehouses and Radio 4's dramatisation of Orwell's 1984. I didn't mean to single out Amazon alone - this is the way modern management is going, and for all of their poor benighted employees. But I really had no idea.

I wasn't aware at the time of the German TV's investigation of the Amazon warehouse there, where migrant workers are kept in order by a semi-military cadre of guards, some of them with disturbing neo-Nazi links. If you don't understand German (I don't), you can read about it in the report by the Independent.

But even then, I wasn't aware of half of it. Across the USA, regional newspapers are investigating the way Amazon runs its warehouses. The Columbia Journalism Review has pulled some of the strands together.

But again, it is one thing to pretend this is a unique phenomenon by a particularly technocratic and monopolistic company. The truth is that this tyrannical Taylorism is emerging in workplaces all over the world, encouraged by the more vacuous management consultants - and measuring how long employees spend in the lavatory is much more common than it seems.

It is also miserably ineffective in the long-run. It wastes all the imagination and common sense of their employees. But that hasn't stopped its onward march.

Nor is this just about intrusive measurement. It is about the whole gamut of Soviet-style organisation, from the pompous marble porticos and telescreens, the doublethink and the Junior Anti-Sex League, the empty dehumanising maxims and, most of all, the simplified language.

Strange that Soviet organisation should be alive and well at the heart of the capitalist world, but the truth is that that kind of dehumanising organisation - first for the poor and powerless and then for the rest of us - was always written into the DNA of both sides in the Cold War. When people struggle with each other, they get like each other - and the worst of our organisations are now horrible like the worst of theirs.

I wasn't aware at the time of the German TV's investigation of the Amazon warehouse there, where migrant workers are kept in order by a semi-military cadre of guards, some of them with disturbing neo-Nazi links. If you don't understand German (I don't), you can read about it in the report by the Independent.

But even then, I wasn't aware of half of it. Across the USA, regional newspapers are investigating the way Amazon runs its warehouses. The Columbia Journalism Review has pulled some of the strands together.

But again, it is one thing to pretend this is a unique phenomenon by a particularly technocratic and monopolistic company. The truth is that this tyrannical Taylorism is emerging in workplaces all over the world, encouraged by the more vacuous management consultants - and measuring how long employees spend in the lavatory is much more common than it seems.

It is also miserably ineffective in the long-run. It wastes all the imagination and common sense of their employees. But that hasn't stopped its onward march.

Nor is this just about intrusive measurement. It is about the whole gamut of Soviet-style organisation, from the pompous marble porticos and telescreens, the doublethink and the Junior Anti-Sex League, the empty dehumanising maxims and, most of all, the simplified language.

Strange that Soviet organisation should be alive and well at the heart of the capitalist world, but the truth is that that kind of dehumanising organisation - first for the poor and powerless and then for the rest of us - was always written into the DNA of both sides in the Cold War. When people struggle with each other, they get like each other - and the worst of our organisations are now horrible like the worst of theirs.

Published on February 23, 2013 02:30

February 22, 2013

Rescuing the Big Society from itself

It has been de rigeur on the left and right to pour scorn on the whole idea of the Big Society. I felt rather differently. I was enormously excited by the Big Society rhetoric when David Cameron first gargled with it, irritated that the Lib Dems had not articulated those things first - voluntarism is a core Liberal idea, after all.

The Big Society was lucky enough to have an articulate, thoughtful and imaginative envoy in Nat Wei, but that was the limit of its advantages. I went to meet some of the people most involved a few weeks into the coalition government, and was so flabbergasted by the lack of depth of the whole thing - the absence of ideological roots - that I found myself almost unable to say anything in reply.

The Big Society had its own roots in the Big Lunch, which was a fantastic project - but it provided very few lessons for public policy except that it would be nice to talk to neighbours now and again.

There seemed to be no understanding, even among the advocates of the Big Society, of the insights since the 1970s of people like Elinor Ostrom, Edgar Cahn, John McKnight and Neva Goodwin - of co-production, asset-based community development and the 'core economy' - and the critique of public services that they represent.

I felt then, and feel even more now, that the Big Society as articulated was far too vague and broad - and it needed to be applied primarily to public services. Especially working out how public services could be organised as engines that could knit society together around them.

So I was fascinated to read the blog by NESTA's Philip Colligan which sets out precisely this in a series of examples, and which coincides with the announcement of NESTA's joint venture with the Cabinet Office, the Centre for Social Action.

This is important stuff, and for all the reasons that Edgar Cahn set out. When services are just delivered one-way, by professionals to grateful and passive recipients, it seems to undermine the power and ability of communities to make things happen. When they allow people to give back, to work alongside professionals delivering services, then the power balance begins to shift.

This seems to me to be a key insight about the future direction of services.

The Big Society was lucky enough to have an articulate, thoughtful and imaginative envoy in Nat Wei, but that was the limit of its advantages. I went to meet some of the people most involved a few weeks into the coalition government, and was so flabbergasted by the lack of depth of the whole thing - the absence of ideological roots - that I found myself almost unable to say anything in reply.

The Big Society had its own roots in the Big Lunch, which was a fantastic project - but it provided very few lessons for public policy except that it would be nice to talk to neighbours now and again.

There seemed to be no understanding, even among the advocates of the Big Society, of the insights since the 1970s of people like Elinor Ostrom, Edgar Cahn, John McKnight and Neva Goodwin - of co-production, asset-based community development and the 'core economy' - and the critique of public services that they represent.

I felt then, and feel even more now, that the Big Society as articulated was far too vague and broad - and it needed to be applied primarily to public services. Especially working out how public services could be organised as engines that could knit society together around them.

So I was fascinated to read the blog by NESTA's Philip Colligan which sets out precisely this in a series of examples, and which coincides with the announcement of NESTA's joint venture with the Cabinet Office, the Centre for Social Action.

This is important stuff, and for all the reasons that Edgar Cahn set out. When services are just delivered one-way, by professionals to grateful and passive recipients, it seems to undermine the power and ability of communities to make things happen. When they allow people to give back, to work alongside professionals delivering services, then the power balance begins to shift.

This seems to me to be a key insight about the future direction of services.

Published on February 22, 2013 03:25

February 21, 2013

Job description for the new NHS chief?

For various different motives, the campaign to force out the NHS chief Sir David Nicholson seems to be gathering pace. The NHS blogger Roy Lilley added his advice to the smouldering fire this morning. But personally, I would be worried about replacing one NHS chief with another in exactly the same mould – unless there was some consensus about what we need instead.

And therein lies the difficulty. Nicholson is a symbol of the command-and-control NHS system which has been found so wanting, the creation of the Blair Brown years. But the coalition has not yet grasped the problems with that system, and has not yet fully articulated a different approach.

The NHS itself yearns to be set free from the straightjacket, but nobody has yet articulated the central philosophy around an alternative.

When it comes to the future of public services, the coalition are still half-in half-out of the old world – understanding some of the difficulties, but still clinging manfully to some of its most destructive tenets (see what I wroteabout some of these).

So let’s imagine for a moment if Sir David Nicholson was to go – and I expect he will retire eventually (most people do) – what kind of person should take over? This is my answer:

Someone who recognises the central importance of the human element. In the end, it isn’t regulations or targets or IT systems which make the difference to healthcare. It is the ability of frontline staff to make effective relationships with patients and with each other, and to use their skills to make a difference. Managers forget that at their peril – and the old dispensation forgot it disastrously. Without those formal levers, the new NHS boss will need to exercise leadership on a whole new scale – but not to claw all the charisma to themselves, but to foster leadership at every level.Someone who understands the importance of flexibility. Not just because flexible services are more able to meet the needs of patients, but because inflexible services are staggeringly wasteful – those long-term patients who are expected to travel to see their consultant every six months, when they don’t need to, but can’t get an appointment when they do need to. Re-think some of those systems, use new kinds of communication – I believe there is this new invention called the telephone – and you might just release the resources that the new NHS needs.Someone who understands the importance of human scale. We need another NHS boss who believes in economies of scale like a hole in the head, when it must be quite obvious that – where economies of scale do exist – they are very rapidly overtaken by the diseconomies of scale. The evidence is that, the bigger the hospital, the more they cost to run – the era of hospital mergers and bigger and ever bigger systems needs to come to an end.

The old dispensation, shaped by Blair and Brown, led to sclerosis and ever higher costs. No, that wasn’t their intention, but that is what happened. It also led to divisions between the frontline and the centre, and continued divisions over disputed words like ‘choice’ – which remain major stumbling blocks even now.

So if we are going to recruit a new chief, we need someone who fully understands the failures of the past and the possibilities of the future. Somebody ought to write a job description – let’s debate it in public. If we do, I'm on the side of these three things: human relationships, flexibility and human scale.

Published on February 21, 2013 07:54

February 20, 2013

Twelve step programme for speculators

The World Development Movement has just launched a clever campaign called Bankers Anonymous, including a Five Step programme to break their addiction to speculating on food.

The only slight quibble I have with this is that the programme turns out to be for us, and not really for the bankers - beginning with writing letters to our poor exhausted MPs. The original Twelve Step programme is what we need here, the one that was originally developed with the help of Carl Jung for alcoholics - and it is directly relevant. It involves recognising the addiction, realising you are powerless to control it, and eventually making amends to the people you have hurt. That is a programme for bankers, not for campaigners (who have their own addictions, but let's leave that on one side).

There is a depth and a truth about the original Twelve Step programme which makes it relevant here, especially now that Barclays seems to have embarked on the first step - which means they have announced that they are no longer going to be involved in speculation on food.

Goldman Sachs, it hardly needs saying, is still speculating away. They made over £250 million last year from raising the price of food, and adding to people's hunger around the world.

The truth is that speculation on anything is actually a great evil. The medieval moralists recognised it, but we have somehow forgotten it. Speculation on agricultural commodities creates uncertainty - precisely what the speculators want - and pushes up the price of food. Speculation on property pushes up the price of homes, and is undermining people's lives over here. It is a rather scary thought but, if property prices in the UK rise in the next 30 years as much as they did in the last 30 years, the price of an average home will stand at £1.2 million. And I don't believe wages will rise that fast.

That is partly because we are not building enough homes. But that is only a small part of the story. It is also because the banks flooded the mortgage market creating house price inflation, because bankers bonuses have ended up largely in property, and because foreign buyers have been speculating in the market. And up the prices go.

If that isn't an urgent issue for the coalition to tackle, I don't know what is.

The only slight quibble I have with this is that the programme turns out to be for us, and not really for the bankers - beginning with writing letters to our poor exhausted MPs. The original Twelve Step programme is what we need here, the one that was originally developed with the help of Carl Jung for alcoholics - and it is directly relevant. It involves recognising the addiction, realising you are powerless to control it, and eventually making amends to the people you have hurt. That is a programme for bankers, not for campaigners (who have their own addictions, but let's leave that on one side).

There is a depth and a truth about the original Twelve Step programme which makes it relevant here, especially now that Barclays seems to have embarked on the first step - which means they have announced that they are no longer going to be involved in speculation on food.

Goldman Sachs, it hardly needs saying, is still speculating away. They made over £250 million last year from raising the price of food, and adding to people's hunger around the world.

The truth is that speculation on anything is actually a great evil. The medieval moralists recognised it, but we have somehow forgotten it. Speculation on agricultural commodities creates uncertainty - precisely what the speculators want - and pushes up the price of food. Speculation on property pushes up the price of homes, and is undermining people's lives over here. It is a rather scary thought but, if property prices in the UK rise in the next 30 years as much as they did in the last 30 years, the price of an average home will stand at £1.2 million. And I don't believe wages will rise that fast.

That is partly because we are not building enough homes. But that is only a small part of the story. It is also because the banks flooded the mortgage market creating house price inflation, because bankers bonuses have ended up largely in property, and because foreign buyers have been speculating in the market. And up the prices go.

If that isn't an urgent issue for the coalition to tackle, I don't know what is.

Published on February 20, 2013 07:55

February 19, 2013

How to get rid of cold callers permanently

For some reason, which I can only guess at, my home telephone has stopped ringing. Why is it? Because everyone I know is at the Eastleigh by-election? Because people only use mobile numbers these days? Because my friends have finally disowned me?

All these are possible, but what I have noticed more than anything else is that - for the last three or four weeks - I have had no cold callers, no telephone salespeople asking me if I am Mrs Boyle, no strange foreign sounding call centres demanding to know whether I have taken out insurance.

I realise there is a conventional way of getting rid of these, which have been coming at the rate of about one a day since I can remember. You join the Telephone Preference Service. That certainly improves matters, but it isn't really enough. This may be hopelessly optimistic on my part, but I believe my phone has been blacklisted by the cold callers.

Since last Autumn, I have tried to get my own back on them - not by putting the phone down, which assists them after all, by speedily allowing them to move on. I always say that I am not, in fact, Mrs Boyle (true, in fact) and that I will get her. I then leave the phone off the hook for an hour or so and listen, with satisfaction, to the call centre struggling to disconnect.

It's a simple process, and quite fun in a mildly cruel way. But I thoroughly recommend it. In fact, if we all did this, these infuriating calls - which waste people's time so outrageously - would become quickly impossible.

Go on.... You know it makes sense!

All these are possible, but what I have noticed more than anything else is that - for the last three or four weeks - I have had no cold callers, no telephone salespeople asking me if I am Mrs Boyle, no strange foreign sounding call centres demanding to know whether I have taken out insurance.

I realise there is a conventional way of getting rid of these, which have been coming at the rate of about one a day since I can remember. You join the Telephone Preference Service. That certainly improves matters, but it isn't really enough. This may be hopelessly optimistic on my part, but I believe my phone has been blacklisted by the cold callers.

Since last Autumn, I have tried to get my own back on them - not by putting the phone down, which assists them after all, by speedily allowing them to move on. I always say that I am not, in fact, Mrs Boyle (true, in fact) and that I will get her. I then leave the phone off the hook for an hour or so and listen, with satisfaction, to the call centre struggling to disconnect.

It's a simple process, and quite fun in a mildly cruel way. But I thoroughly recommend it. In fact, if we all did this, these infuriating calls - which waste people's time so outrageously - would become quickly impossible.

Go on.... You know it makes sense!

Published on February 19, 2013 11:59

February 18, 2013

Were slaves too good to pick cotton?

I admire Iain Duncan-Smith, both for his determination and his commitment to the central issue - which is how the welfare system can undermine individuals and communities at the same time as rescuing them.

I have no problem with the idea that we should expect people on benefits to do something useful - that is a major improvement on the old idea, which is they should moulder away idle and 'available for work' without actually doing any.

But what was he thinking about in his outburst over the weekend? When you require somebody to stop working with a museum and work instead stacking shelves at Poundland, of course they are going to complain about it. They are not "too good to stack shelves". Did the slaves in the Deep South feel they were too good to pick cotton? No, they objected to being enslaved.

The issue here is not whether or not people should do something in return for the basic money to support life. There is a moral obligation that they should, and benefits regulations that prevent them are complicit in undermining their lives. The real issue is whether the state has the right to move them from useful work to a technocratic system of labour - as if that was the only real work for poor people.

I wrote about the link between Amazon and Big Brother yesterday, and - listening to the dramatisation of 1984 on the radio yesterday - the links between modern workplaces and Orwell's dystopia seem even clearer. The mindless slogans, the marble porticos, the sudden disappearances, the doublethink, the endless measurement and the telescreens. Some work is like that - de-humanising, wasteful of the human spirit.

The big problem about work as designed by the time and motion pioneer Frederick Winslow Taylor is that it only uses half the workers - it entirely wastes their imagination, common sense, knowledge and humanity. So here is the issue: does the state have the right to force you to do de-humanising work when you already have useful work? Can the DWP only recognise work when it is packaged, measured, monitored and thoughtless, and not when it involves other attributes than mere brawn?

Or are they waiting for their claimants to succumb. To be able to say, as Orwell did about Winston Smith: "Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Poundland. Or Tesco. Or Amazon or any of the others..."

I have no problem with the idea that we should expect people on benefits to do something useful - that is a major improvement on the old idea, which is they should moulder away idle and 'available for work' without actually doing any.

But what was he thinking about in his outburst over the weekend? When you require somebody to stop working with a museum and work instead stacking shelves at Poundland, of course they are going to complain about it. They are not "too good to stack shelves". Did the slaves in the Deep South feel they were too good to pick cotton? No, they objected to being enslaved.

The issue here is not whether or not people should do something in return for the basic money to support life. There is a moral obligation that they should, and benefits regulations that prevent them are complicit in undermining their lives. The real issue is whether the state has the right to move them from useful work to a technocratic system of labour - as if that was the only real work for poor people.

I wrote about the link between Amazon and Big Brother yesterday, and - listening to the dramatisation of 1984 on the radio yesterday - the links between modern workplaces and Orwell's dystopia seem even clearer. The mindless slogans, the marble porticos, the sudden disappearances, the doublethink, the endless measurement and the telescreens. Some work is like that - de-humanising, wasteful of the human spirit.

The big problem about work as designed by the time and motion pioneer Frederick Winslow Taylor is that it only uses half the workers - it entirely wastes their imagination, common sense, knowledge and humanity. So here is the issue: does the state have the right to force you to do de-humanising work when you already have useful work? Can the DWP only recognise work when it is packaged, measured, monitored and thoughtless, and not when it involves other attributes than mere brawn?

Or are they waiting for their claimants to succumb. To be able to say, as Orwell did about Winston Smith: "Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Poundland. Or Tesco. Or Amazon or any of the others..."

Published on February 18, 2013 02:05

February 16, 2013

Amazon and Big Brother

It was almost exactly 110 years ago, 23 June 1903, in the United States Hotel in Saratoga, New York, that Frederick Winslow Taylor rose to address a meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers on the subject of 'Shop Management'.

It was almost exactly 110 years ago, 23 June 1903, in the United States Hotel in Saratoga, New York, that Frederick Winslow Taylor rose to address a meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers on the subject of 'Shop Management'.By 'shop', Taylor meant 'shop floor'. As far as he was already known to the meeting, it was as a controversial industrial manager who was supposed to have worked miracles of productivity at the giant Bethlehem Steel plant in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, churning out iron plating for the world's battleships, from where he had recently been dismissed. His ideas were known then as 'scientific management'.

That meant breaking every task down into units, measuring how long they take and setting targets for workers to meet. These techniques have long since broken out of factories, and you can see them working in the new call-centres, and in the NHS targets, school league tables, sustainability indicators and the battery of statistics by which public services are now run all over the Western world. And in the fearsome warehouses of the new IT world.

That meant breaking every task down into units, measuring how long they take and setting targets for workers to meet. These techniques have long since broken out of factories, and you can see them working in the new call-centres, and in the NHS targets, school league tables, sustainability indicators and the battery of statistics by which public services are now run all over the Western world. And in the fearsome warehouses of the new IT world.Taylorism is the philosophy behind the whiff of slavery described by Zoe Williams in the Guardian last week, when she lifted the lid on the warehouses run by Amazon and Tesco, which time their miserable employees in everything they do, even going to the toilet (though Tesco assures her that they turn off the electronic tags while they are actually in there).

The information was in a fascinating article in the Financial Times about Amazon's new Rugeley warehouse, which describes the tags like this:

"Others found the pressure intense. Several former workers said the handheld computers, which look like clunky scientific calculators with handles and big screens, gave them a real-time indication of whether they were running behind or ahead of their target and by how much. Managers could also send text messages to these devices to tell workers to speed up, they said. “People were constantly warned about talking to one another by the management, who were keen to eliminate any form of time-wasting,” one former worker added."

The vision of these people, jogging between tasks to desperately earn the elusive permanent employee status (which gives them a pension as well as 1p an hour more than the minimum wage), reminds me overwhelmingly of Big Brother. The tele-screens, the thought crimes, not to mention the blow up doll at the Amazon reception desk with a speech bubble which says 'this is the best job I ever had'. Meeting the targets set by the machines is a tough and sweaty business.

We haven't quite grasped that, when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, it still hadn’t come down in our own world. Even the management pioneer Tom Peters described working in Siemens, which was the inspiration for his first book, as “the closest thing to working for a communist state”. Those great marble edifices, the corporate fear, the mindless maxims, and the management consultants measuring measuring measuring. It is more like North Korea than North Europe.

We are minor victims of this Big Brother world, the continuation of Soviet government, nearly every day, when we deal with call centres who can’t grasp what we need because their software doesn’t recognise it. But there are bigger victims too, whether they are call centre staff measured for the minutes they take going to the lavatory, or the employees of Amazon told by their Big Brother electronic tag to stop talking to each other.

This is one of the tragedies of Taylorism. When we work for the system, it demands that we re-organise our lives and beliefs around an illusion of efficiency. When we deal with it, it demands that we reshape ourselves into the rational one-dimension that is easy to process. That was the insight of the poet David Whyte, who was among the first to make the link between the Soviet system and modern work:

"The old corporate world now passing away had become for us a form of ritual, almost religious life… It asked us to give up our own desires. To pay no heed to our bodily experience. To think abstractly, to put organisational goals above home and family, and, like many institutional religions, it asked us not to be too troubled by any questionable activity.”

More about this in my book The Human Element. But Whyte was wrong about it passing away. To anyone listening to the Radio 4 dramatisation of Orwell's 1984 this weekend, the parallels with Amazon and Tesco and the future of work for all of us if we're not careful, are too overwhelming to ignore.

Published on February 16, 2013 14:10

The secret law governing London's traffic

I sometimes wonder why on earth I stay a member of the AA. Their breakdown service is usually very good, but they take my membership and use it to imply that I agree with their rather dysfunctional views on motoring - which seems to me that there should be no restraints to it.

They claim rather disingenuously that they are not against the London congestion charge, but this is the story they generated yesterday pouring scorn on the whole idea - arguing that it has extracted £2.6 billion from motorists over the past decade without actually reducing congestion.

Well, I have to reveal to them what clearly remains a secret - congestion was always going to stay the same if it means average journey times. It always has been the same, for the past century - an average of around 12 mph. Because there is a reason why that should be. There is another 'hidden hand', but not an economic one, and the man who helped uncover what it was and helped to popularise the answer was one of the most unusual transport planners of the century.

Martin Mogridge was originally a physicist who wore long hair and leather trousers, with a cultivated air of exoticism. His interests included science fiction and Victorian eroticism, and just before his untimely death in 1999 at the age of only 59, he began studying Hebrew.

Over the previous three decades, while the major cities of the world enthusiastically demolished their slums and built massive urban highways, transport experts had been puzzling over the phenomenon of how new roads – even widened roads – seemed to increase traffic. Economists had noticed that, if there is more road space, then people find it worthwhile to pay to use their cars, if they had one. Then public transport attracts fewer paying passengers and the fares go up or services reduce, and even more people go by car. Even in the 1930s, they had noticed that new roads released what they called ‘suppressed demand’. Worse, then the traffic goes faster and the buses find it more difficult to negotiate traffic streams or cross big highways.

That was a vital clue: the speed of road transport and public transport are linked, and the journey times door to door for both are often very similar. Mogridge realised that, in London, everything depended on the speed of the underground system. If you build more roads, people go back to their cars because it is then quicker than going by underground – until the point when the speed is so slow that underground travel is faster. Then they leave their cars behind and go by tube.

The solution to speeding up the traffic is therefore to speed up the main public transport infrastructure. What’s more, said Mogridge, this works even if you take space away from cars to make room for public transport. It was the thinking that led to Zurich’s successful strategy to reduce car use based on better pedestrian access and investment in trams. By the end of his life, Mogridge reckoned that traffic speed could be doubled just by reducing space for cars, though it remains difficult for public officials – at least in the UK – to act on this new law of traffic management.

If Mogridge was right, the likely effect of the congestion charge zone in London would have been to cut traffic a little, but leave journey times exactly the same - and so it proved. Now we can move onto the next conundrum: why do these bone-headed types at the AA think that my only interests are those of a motorist - and not as a father, a citizen and an asthmatic?

Find out more in my book The New Economics.

They claim rather disingenuously that they are not against the London congestion charge, but this is the story they generated yesterday pouring scorn on the whole idea - arguing that it has extracted £2.6 billion from motorists over the past decade without actually reducing congestion.

Well, I have to reveal to them what clearly remains a secret - congestion was always going to stay the same if it means average journey times. It always has been the same, for the past century - an average of around 12 mph. Because there is a reason why that should be. There is another 'hidden hand', but not an economic one, and the man who helped uncover what it was and helped to popularise the answer was one of the most unusual transport planners of the century.

Martin Mogridge was originally a physicist who wore long hair and leather trousers, with a cultivated air of exoticism. His interests included science fiction and Victorian eroticism, and just before his untimely death in 1999 at the age of only 59, he began studying Hebrew.

Over the previous three decades, while the major cities of the world enthusiastically demolished their slums and built massive urban highways, transport experts had been puzzling over the phenomenon of how new roads – even widened roads – seemed to increase traffic. Economists had noticed that, if there is more road space, then people find it worthwhile to pay to use their cars, if they had one. Then public transport attracts fewer paying passengers and the fares go up or services reduce, and even more people go by car. Even in the 1930s, they had noticed that new roads released what they called ‘suppressed demand’. Worse, then the traffic goes faster and the buses find it more difficult to negotiate traffic streams or cross big highways.

That was a vital clue: the speed of road transport and public transport are linked, and the journey times door to door for both are often very similar. Mogridge realised that, in London, everything depended on the speed of the underground system. If you build more roads, people go back to their cars because it is then quicker than going by underground – until the point when the speed is so slow that underground travel is faster. Then they leave their cars behind and go by tube.

The solution to speeding up the traffic is therefore to speed up the main public transport infrastructure. What’s more, said Mogridge, this works even if you take space away from cars to make room for public transport. It was the thinking that led to Zurich’s successful strategy to reduce car use based on better pedestrian access and investment in trams. By the end of his life, Mogridge reckoned that traffic speed could be doubled just by reducing space for cars, though it remains difficult for public officials – at least in the UK – to act on this new law of traffic management.

If Mogridge was right, the likely effect of the congestion charge zone in London would have been to cut traffic a little, but leave journey times exactly the same - and so it proved. Now we can move onto the next conundrum: why do these bone-headed types at the AA think that my only interests are those of a motorist - and not as a father, a citizen and an asthmatic?

Find out more in my book The New Economics.

Published on February 16, 2013 09:38

February 15, 2013

My lamp-posts and the graph of doom

I happened to hear various interviews yesterday on the BBC about the local government settlement, and you have to agonize about it. The so-called Graph of Doom, which I have written about before, is pretty graphic (as they say).

I find myself wondering whether the real story of these years, the one told by historians, will be about the way public services struggle to adapt to the financial holocaust - not about austerity (though that doesn't help) but because of the staggering inflation of public service costs. They will do so using the new localism powers given to local government, but the jury remains out about whether they will succeed or not.

Then I drove back down my own unadopted road, with its muddy potholes, and there was a big lorry from Croydon Council putting in tall new lamp-posts. They have not torn out the beautiful old silver painted, ornate ones from 1937, but they will.

This staggering waste of money will, I am sure, provide us with better light - which we don't need. It is also, I am sure, replacing the old adapted lamps with more energy efficient ones (though who knows).

But one quick glance at the top of the big black lamps shows the real waste. No solar cells. These staggeringly wasteful lamps will not generate their own electricity, and will soon have to be replaced all over again by lamps which do.

It is moments like these when I wonder how much local government is the agent of its own destruction. But then, maybe it is just Croydon. They are withdrawing funding from my much-loved local library but, at the same time, they are putting in expensive new lamps which we don't need, don't want and which will be obsolete before the tarmac dries around them.

I find myself wondering whether the real story of these years, the one told by historians, will be about the way public services struggle to adapt to the financial holocaust - not about austerity (though that doesn't help) but because of the staggering inflation of public service costs. They will do so using the new localism powers given to local government, but the jury remains out about whether they will succeed or not.

Then I drove back down my own unadopted road, with its muddy potholes, and there was a big lorry from Croydon Council putting in tall new lamp-posts. They have not torn out the beautiful old silver painted, ornate ones from 1937, but they will.

This staggering waste of money will, I am sure, provide us with better light - which we don't need. It is also, I am sure, replacing the old adapted lamps with more energy efficient ones (though who knows).

But one quick glance at the top of the big black lamps shows the real waste. No solar cells. These staggeringly wasteful lamps will not generate their own electricity, and will soon have to be replaced all over again by lamps which do.

It is moments like these when I wonder how much local government is the agent of its own destruction. But then, maybe it is just Croydon. They are withdrawing funding from my much-loved local library but, at the same time, they are putting in expensive new lamps which we don't need, don't want and which will be obsolete before the tarmac dries around them.

Published on February 15, 2013 01:49

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.