David Boyle's Blog, page 87

March 18, 2013

What the end of post-modernism really means

What comes after post-modernism? I asked a couple of posts ago - and did so partly to encourage people to buy my book which (I modestly suggests) contains the answer.

I've had a number of completely contradictory responses - congratulatory messages on Facebook, a cascade of articles about the impossibility of objective truth, and defending the prevailing post-modern culture. For Liberals, these are difficult issues - because I am suggesting there is a lazy, corrosive kind of liberalism, and we need to move beyond it to find a high, more demanding Liberalism, a Liberalism with depth, which has some chance of surviving another century.

I also had a number of comments from people who said that they hadn't the faintest idea what I am talking about. This seems to be to be rather a fair criticism. So I thought I would develop the following table, which tries to explain how we have moved from a tyrannical modernism to a lazy and corrosive post-modernism - and will inevitably move to what I suggest is a new kind of humanism:

The ages at a glance

Modernist Post-modernist New Humanist Emerging nation Germany France UK Presiding ethic Truth Tolerance Wholeness Besetting sin Tidiness Relativism Obscurity Inspiring technology Assembly line Internet Solar cell Primary language Architecture Literature Narrative Presiding genius Walter Gropius Jacques Derrida David Bohm Cheerleader Roger Fry Charles Jencks Position vacant

Since publishing the book, I have wondered whether the besetting sin of the new humanism is really obscurity, after all. I'm not sure it isn't actually going to be pomposity - this is after all the sin of people who believe they are in communication with objective truth. So I am going to be very careful from now on not to be either obscure or pompous if I can possibly help it.

But do feel free to join in the real debate about the future: read The Age to Come: Authenticity, Post-modernism and how to survive what comes next (Endeavour Press). And let me know what you think!

I've had a number of completely contradictory responses - congratulatory messages on Facebook, a cascade of articles about the impossibility of objective truth, and defending the prevailing post-modern culture. For Liberals, these are difficult issues - because I am suggesting there is a lazy, corrosive kind of liberalism, and we need to move beyond it to find a high, more demanding Liberalism, a Liberalism with depth, which has some chance of surviving another century.

I also had a number of comments from people who said that they hadn't the faintest idea what I am talking about. This seems to be to be rather a fair criticism. So I thought I would develop the following table, which tries to explain how we have moved from a tyrannical modernism to a lazy and corrosive post-modernism - and will inevitably move to what I suggest is a new kind of humanism:

The ages at a glance

Modernist Post-modernist New Humanist Emerging nation Germany France UK Presiding ethic Truth Tolerance Wholeness Besetting sin Tidiness Relativism Obscurity Inspiring technology Assembly line Internet Solar cell Primary language Architecture Literature Narrative Presiding genius Walter Gropius Jacques Derrida David Bohm Cheerleader Roger Fry Charles Jencks Position vacant

Since publishing the book, I have wondered whether the besetting sin of the new humanism is really obscurity, after all. I'm not sure it isn't actually going to be pomposity - this is after all the sin of people who believe they are in communication with objective truth. So I am going to be very careful from now on not to be either obscure or pompous if I can possibly help it.

But do feel free to join in the real debate about the future: read The Age to Come: Authenticity, Post-modernism and how to survive what comes next (Endeavour Press). And let me know what you think!

Published on March 18, 2013 03:53

March 17, 2013

Tough on press abuse, tough on the causes of press abuse

Am I missing something here? We have the main political parties arguing over press regulation like St Anselm arguing over how many angels were on the head of a pin. But the causes of media abuse - the outrageous hold that the Murdoch press had over politicians - goes unremarked.

What badly needs debate is precisely how to regulate cross-media ownership better, and how to prevent semi-monopolies of influence from building up that subverts proper media balance - and prevents prime ministers paying court to one press baron and his acolytes in particular.

As always, the most important Liberal issue - monopoly power - gets ignored in the flurry of irrelevant parliamentary excitement.

It isn't that Leveson ignored concentrated ownership, or that there has been no mention of it - Ed Miliband proposed a limit of 30 per cent of any one media type (Murdoch has 34 per cent of national newspapers) which seems to be puny.

There is also an argument that too much anti-trust will undermine the survival of our national newspapers. Maybe - it needs to be argued out. So why isn't it?

Is it because politicians are hopelessly obsessed with the particular? If they can prevent Milly Dowler's phone being hacked again, they feel they can somehow clap themselves on the back and say 'job done'?

Is it because those who want to prevent the ownership debate from happening have deliberately shifted onto this theological issue which so fundamentally misses the point?

Is it because monopoly power is always the dog that doesn't bark - because Labour and Conservatives alike are blind to the Liberal issue of concentrations of power?

Or is it that they want to get back to normality: riding in the countryside with Rebekah Brooks?

There is a kneejerk political temptation to debate regulation rather than tackling fundamental causes - but it doesn't explain this terrible blindness.

So I am going to sleep through the utterly pointless debate tomorrow. Who is going to join me?

What badly needs debate is precisely how to regulate cross-media ownership better, and how to prevent semi-monopolies of influence from building up that subverts proper media balance - and prevents prime ministers paying court to one press baron and his acolytes in particular.

As always, the most important Liberal issue - monopoly power - gets ignored in the flurry of irrelevant parliamentary excitement.

It isn't that Leveson ignored concentrated ownership, or that there has been no mention of it - Ed Miliband proposed a limit of 30 per cent of any one media type (Murdoch has 34 per cent of national newspapers) which seems to be puny.

There is also an argument that too much anti-trust will undermine the survival of our national newspapers. Maybe - it needs to be argued out. So why isn't it?

Is it because politicians are hopelessly obsessed with the particular? If they can prevent Milly Dowler's phone being hacked again, they feel they can somehow clap themselves on the back and say 'job done'?

Is it because those who want to prevent the ownership debate from happening have deliberately shifted onto this theological issue which so fundamentally misses the point?

Is it because monopoly power is always the dog that doesn't bark - because Labour and Conservatives alike are blind to the Liberal issue of concentrations of power?

Or is it that they want to get back to normality: riding in the countryside with Rebekah Brooks?

There is a kneejerk political temptation to debate regulation rather than tackling fundamental causes - but it doesn't explain this terrible blindness.

So I am going to sleep through the utterly pointless debate tomorrow. Who is going to join me?

Published on March 17, 2013 04:27

March 16, 2013

What is coming after post-modernism

We live in simultaneous ages, and sometimes they are only given names when we are dead and gone. It is peculiar that we should live in a country and never be told its name.

We live in simultaneous ages, and sometimes they are only given names when we are dead and gone. It is peculiar that we should live in a country and never be told its name.The Renaissance historians named the ‘dark ages’ and ‘middle ages’ that had gone before. Modern historians have their ‘Victorian Age’ or ‘Age of the Enlightenment’. Most of us think more in terms of decades. But there are other ages and in some ways they are more meaningful, because they sum up the prevailing philosophies of life that dominate the moment in time that is ours.

The great cultural movements start with a flicker of interest in the avant garde, reacting against the prevailing abominations. Then they grow to dominate thinking in politics, the arts, literature, design, marketing and even economics and politics. Then they are in turn swept away by the next prevailing philosophy, and which answer people’s need for direction, frameworks, attitude and much more.

For those of us with a short attention span, these great philosophical ages might come and go unnoticed every half a century or so, perhaps less. They are heralded and die, unremarked by the mass of humanity. But they are potent – and much more potent than you would think for the earnest and obscure debate about them among earnest and obscure academics.

I was born in 1958. It was the year of Sputnik and CND but it was also the time that modernism had finally emerged from the hothouse of German architecture salons, arts cafés, and intellectual magazines.

Throughout my childhood, the transformation of modernism from avant garde obscurity into a prevailing philosophy for urban living was emerging, and the sounds of battle were everywhere. There was Jane Jacobs and her fellow New York mothers challenging city planner Robert Moses and his plan for urban motorways. There was the poet John Betjeman, defending the doomed Euston Arch, and whose Collected Poems became a bestseller that year. The very word ‘progress’ seemed to have been co-opted by the modernist forces, in unstoppable alliance with the developers and highway planners.

But there came a point when the challenge became overwhelming, and the architectural critic Charles Jencks dated that moment very specifically: “Modern architecture died in St Louis, Missouri on July 15 1972 at 3.32 pm (or thereabouts),” he wrote.

Jencks was the prophet of what he called ‘post-modernism’, but it was architecture he was particularly interested in. The date he chose for the end of one philosophical age and the start of another was the moment of the planned explosion that demolished the Pruitt-Igoe Flats in Chicago, one of the most egregious examples of modernism as prisons for the poor. But that was back in 1972. It was much clearer a decade after the destruction of Pruitt-Igue that some new approach was emerging.

I first grasped what post-modernism might be when I saw the strange pastiche of ancient Egyptian art that was the new Homebase store in Kensington around 1985. You could see the same underlying objectives in the pastiche buildings, like Robert Venturi’s Chippendale-style skyscraper. The modernists regarded this as an outrageous betrayal of their values.

But here is the question. If post-modernism is the defining frame for our own age, then what is coming next? Can we see something emerging already? My answer is that we can, and exactly what it is – and how it will affect our lives – is in my new ebook The Age to Come: Authenticity, Post-Modernism and How To Survive What Comes Next , published by Endeavour Press, and it follows up the arguments I made ten years ago in Authenticity .

We are deep inside the post-modern age now. It is hard to imagine a style that is somehow different from the Art Deco pastiches, the Tudor pastiches, the classical pastiches going up in concrete everywhere we look. Or the novels about sad middle-aged men that take place simultaneously now and in 1848. Or the bizarre inability of the fine arts world to go beyond épater les bourgeois, when the bourgeois they wanted to shock have long since packed up and left the stage.

The fine arts world gives the game away. Modernism reached its zenith when the money began to follow it. It became no longer a brave critique of the status quo, but the status quo itself. The same thing has happened to post-modernism, now that the Brit Art revolution – with its irony and jokes – has become the establishment.

It is no longer a brave critique of modernism, an ironic understanding of the social construction of reality, a response to the linguistic philosophies of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. It is where the money is, riding the virtual wave, virtual reality and all the rest. It sits on the throne and dominates our lives. So the time cannot be too far away when it becomes a caricature of itself, and – with another great intellectual clash – dissolves into history, leaving behind the seeds of the next age.

What comes next will dominate our children’s lives, and maybe our grandchildren’s lives as well, before it eventually compromises with the prevailing economic orthodoxy as well, and is swept away in its turn.

The next age, the coming age, will try to challenge our contemporary conviction that nothing is true and everything is relative. It will not reach back hopelessly to previous ages of certainty, though people may accuse it of that: we have lost our innocence about social reality.

It will not pretend it is somehow possible to work out unambiguously what is true in this world. It will not turn its back on the understanding and tolerance we have generated with the social construction of knowledge. But it will not be limited by that any more.

We are moving into an age that will try to satisfy our need for what we have lost, looking around for something we can be sure of – something we can use to measure everything else against – and it is beginning to find it in ourselves and our humanity, and will use that to seek a way out of the paralysis of post-modernism.

How do I know? Because although the new age is not yet upon us, the critique of post-modernism is beginning to emerge that will bring a new project – and these great ages are, each of them, a project to find directions out of the dead ends thrown up by the project before.

We can’t know for sure the parameters of the coming age – the new age of humanism – but we can begin to glimpse a few features. And, as they say, forewarned is forearmed...

The Age to Come is a book of recent essays, and it suggests that the first shoots are emerging of a new age which looks set to sweep post-modernism away, based on depth, authenticity and human relationships, which will change the lives of our children completely. See what you think and let me know...

Published on March 16, 2013 02:48

March 15, 2013

How Miliband stole a march on local banks

I would be staggered if Ed Miliband ever read any of these blogs. I would be even more astonished if Ed Balls or any of those other monsters of deficit had done so. So it must be largely coincidence that, 48 hours after I wrote my blog on doomed lending measures that were still trying to use the defunct lending infrastructure of the big banks - the Labour leader should call for a new regional banking infrastructure.

This is the central economic issue of the moment - the most important thing a UK government could do to boost the economy (I say 'UK' government because most other European countries already have a regional lending infrastructure).

So although I'm glad Miliband has come out and said it, I am frustrated that the coalition has allowed him to do so.

It wasn't as if this is a new idea. The coalition agreement says:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals to foster diversity, promote mutuals and create a more competitive banking industry."

It was in the Lib Dem manifesto. But bizarrely, most politicians - Lib Dem and Labour - are clinging to the idea that they can force the banks to lend to small businesses, quite oblivious to the truth that they are no longer geared up to do so. They have no local infrastructure - that's why we need a new one.

There is a new clause in the Financial Services Bill which lays a duty on the regulator to make sure the banking industry is diverse, thanks largely to Susan Kramer and colleagues, but that is all. We are three years into the coalition, and still there are no bold proposals to create an effective lending infrastructure. Yes, it is frustrating.

So if he didn't read it here, what explains Miliband's sudden conversion to local banking? Especially as Ed Balls used to describe these ideas as 'jurassic' - by which I believe he meant they were a little out of date.

The answer that Maurice Glassman is more influential that he seems and Labour's small business task force has recommended it, and he seems to have used the opportunity of his Newcastle speech to run with the idea. There is a lesson here about how policy gets made: something about opportunities and having the right conversation at the right time.

I hope the coalition will now bring forward their own plans, preferably using a broken up RBS as the basis for a new regional banking network.

I hope Ed Balls is also onside now. Nobody wants to find they are the jurassic one after all.

This is the central economic issue of the moment - the most important thing a UK government could do to boost the economy (I say 'UK' government because most other European countries already have a regional lending infrastructure).

So although I'm glad Miliband has come out and said it, I am frustrated that the coalition has allowed him to do so.

It wasn't as if this is a new idea. The coalition agreement says:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals to foster diversity, promote mutuals and create a more competitive banking industry."

It was in the Lib Dem manifesto. But bizarrely, most politicians - Lib Dem and Labour - are clinging to the idea that they can force the banks to lend to small businesses, quite oblivious to the truth that they are no longer geared up to do so. They have no local infrastructure - that's why we need a new one.

There is a new clause in the Financial Services Bill which lays a duty on the regulator to make sure the banking industry is diverse, thanks largely to Susan Kramer and colleagues, but that is all. We are three years into the coalition, and still there are no bold proposals to create an effective lending infrastructure. Yes, it is frustrating.

So if he didn't read it here, what explains Miliband's sudden conversion to local banking? Especially as Ed Balls used to describe these ideas as 'jurassic' - by which I believe he meant they were a little out of date.

The answer that Maurice Glassman is more influential that he seems and Labour's small business task force has recommended it, and he seems to have used the opportunity of his Newcastle speech to run with the idea. There is a lesson here about how policy gets made: something about opportunities and having the right conversation at the right time.

I hope the coalition will now bring forward their own plans, preferably using a broken up RBS as the basis for a new regional banking network.

I hope Ed Balls is also onside now. Nobody wants to find they are the jurassic one after all.

Published on March 15, 2013 05:23

March 14, 2013

Why press monopoly is much more dangerous

I remember reading a letter to the Evening Standard in 2007 which highlighted the problem of monopoly.

The man who wrote it was describing his girlfriend’s flight from Romania to Heathrow by British Airways. BA (a privatised utility) had changed planes at Romania and had failed to put anyone’s bags on board. The crew knew this, but still the passengers were allowed to wait hopelessly at the carousel for two hours for their non-existent baggage, which BA staff knew perfectly well was not going to arrive. It actually took three days to get them.

What do you do about that kind of thing? Well, you can regulate - and that makes some sense - but what really needs to happen is to look at the structural reasons. BA is too big. Heathrow is a nightmare. The flights from Romania are operated by only one airline. And so on.

I thought of this listening to the argument this evening about press regulation. It isn't that press regulation is unimportant. It certainly needs to happen. But it is far less important than tackling the central issue, which is the concentration of media power into only a few hands, which means that regulators get muzzled by frightened politicians.

Because monopoly power is a Liberal issue - neither Conservatives nor Labour politicians really understand its importance - the whole debate tends to surround the relatively irrelevant issue of regulation.

Leveson made recommendations about breaking up media ownership. Lib Dems have made speeches about it. But still the core of the debate is elsewhere, which is after all just what Murdoch and Rothermere and all the rest want.

So let's take part in the debate about regulation, but don't let this overshadow the far more important aspect: a good press is a diverse press, owned as widely as possible - which does not allow press barons to collect the media into their hands alone. Tackle that one and regulation becomes a good deal less fraught.

The man who wrote it was describing his girlfriend’s flight from Romania to Heathrow by British Airways. BA (a privatised utility) had changed planes at Romania and had failed to put anyone’s bags on board. The crew knew this, but still the passengers were allowed to wait hopelessly at the carousel for two hours for their non-existent baggage, which BA staff knew perfectly well was not going to arrive. It actually took three days to get them.

What do you do about that kind of thing? Well, you can regulate - and that makes some sense - but what really needs to happen is to look at the structural reasons. BA is too big. Heathrow is a nightmare. The flights from Romania are operated by only one airline. And so on.

I thought of this listening to the argument this evening about press regulation. It isn't that press regulation is unimportant. It certainly needs to happen. But it is far less important than tackling the central issue, which is the concentration of media power into only a few hands, which means that regulators get muzzled by frightened politicians.

Because monopoly power is a Liberal issue - neither Conservatives nor Labour politicians really understand its importance - the whole debate tends to surround the relatively irrelevant issue of regulation.

Leveson made recommendations about breaking up media ownership. Lib Dems have made speeches about it. But still the core of the debate is elsewhere, which is after all just what Murdoch and Rothermere and all the rest want.

So let's take part in the debate about regulation, but don't let this overshadow the far more important aspect: a good press is a diverse press, owned as widely as possible - which does not allow press barons to collect the media into their hands alone. Tackle that one and regulation becomes a good deal less fraught.

Published on March 14, 2013 11:17

March 13, 2013

More doomed schemes for bank lending

I stood in the gallery at the Brighton Metropole during the Lib Dem conference last weekend, while my eight-year-old read a Beastquest book at my feet, and listened to Nick Clegg doing his Q&A on the economy.

I missed the kerfuffle about secret courts which came later, and I wrote yesterday how impressive I thought he was. He has enough problems without me offering him advice, but his support for the Funding for Lending scheme was profoundly wrong, and I need to say why.

Politicians in power tend to think their efforts are somehow in proportion to the amount of money they are spending. It must feel like that to them. Because £68 billion has been made available to lower the costs of lending for banks, it must be hugely significant. It isn't - it is a major irrelevance.

It is irrelevant because the big banks are no longer set up to lend to small, productive business.

How can I put it more clearly? They don't have the infrastructure, the managers on the ground who know the local economy. They can only judge applications by national criteria which tell them not to lend. The banks are set up to re-create the conditions for the last asset boom and ride the wave. They are not useful infrastructure any more for rebuilding the economy.

Then, about 36 hours after I was in Brighton, the figures confirmed what I say. The banks have drawn on only a fifth of the money and net lending has actually contracted by £2.4 billion.

I know serving politicians find it difficult to see outside the existing institutions. But there is now no more important issue for the Lib Dems, politically and economically, than providing an effective lending infrastructure for small business. What the political parties have to grasp - and I don't know why they have been so slow on the uptake - is that the big banks are not dragging their feet. They are not somehow persuadable to lend more. They are no longer geared up to do so.

Ever since they came into office, the coalition has invented more labyrinthine schemes to encourage them to lend, from Project Merlin onwards. They don't work, but still the penny hasn't dropped and it is now almost too late for them to make anything happen in time for the election.

Even the Treasury is showing signs of understanding the basic problem, but the political will to tackle it seems to be lacking - because the politicians prefer to be cross with bankers than to understand the problem and do something about it.

This is what they have to do. RBS has to be split up into effective regional lenders before it is privatised. But most important, the banks have to be cajolled into creating the community banking infrastructure that can lend where they can't - as they do under the Community Reinvestment Act in the USA. The community development finance institutions in the USA are able to get money to where it is most effective within weeks.

Here is the real point. There is no more important economic issue than the need for local and regional institutions capable of lending. Other European countries have it, but we don't. Some of the basic work has been done as Susan Kramer explained recently. But ministers - and Lib Dem ministers in particular - need to understand the basic problem, and then it can be solved.

It would be a tragedy if our party had spent five years in power, endlessly reinventing doomed schemes to help the big banks lend more - then the real problem is they can't.

I missed the kerfuffle about secret courts which came later, and I wrote yesterday how impressive I thought he was. He has enough problems without me offering him advice, but his support for the Funding for Lending scheme was profoundly wrong, and I need to say why.

Politicians in power tend to think their efforts are somehow in proportion to the amount of money they are spending. It must feel like that to them. Because £68 billion has been made available to lower the costs of lending for banks, it must be hugely significant. It isn't - it is a major irrelevance.

It is irrelevant because the big banks are no longer set up to lend to small, productive business.

How can I put it more clearly? They don't have the infrastructure, the managers on the ground who know the local economy. They can only judge applications by national criteria which tell them not to lend. The banks are set up to re-create the conditions for the last asset boom and ride the wave. They are not useful infrastructure any more for rebuilding the economy.

Then, about 36 hours after I was in Brighton, the figures confirmed what I say. The banks have drawn on only a fifth of the money and net lending has actually contracted by £2.4 billion.

I know serving politicians find it difficult to see outside the existing institutions. But there is now no more important issue for the Lib Dems, politically and economically, than providing an effective lending infrastructure for small business. What the political parties have to grasp - and I don't know why they have been so slow on the uptake - is that the big banks are not dragging their feet. They are not somehow persuadable to lend more. They are no longer geared up to do so.

Ever since they came into office, the coalition has invented more labyrinthine schemes to encourage them to lend, from Project Merlin onwards. They don't work, but still the penny hasn't dropped and it is now almost too late for them to make anything happen in time for the election.

Even the Treasury is showing signs of understanding the basic problem, but the political will to tackle it seems to be lacking - because the politicians prefer to be cross with bankers than to understand the problem and do something about it.

This is what they have to do. RBS has to be split up into effective regional lenders before it is privatised. But most important, the banks have to be cajolled into creating the community banking infrastructure that can lend where they can't - as they do under the Community Reinvestment Act in the USA. The community development finance institutions in the USA are able to get money to where it is most effective within weeks.

Here is the real point. There is no more important economic issue than the need for local and regional institutions capable of lending. Other European countries have it, but we don't. Some of the basic work has been done as Susan Kramer explained recently. But ministers - and Lib Dem ministers in particular - need to understand the basic problem, and then it can be solved.

It would be a tragedy if our party had spent five years in power, endlessly reinventing doomed schemes to help the big banks lend more - then the real problem is they can't.

Published on March 13, 2013 03:09

March 12, 2013

Clegg versus Huhne five years on

I have been keeping this blog now for more than five years, sometimes more enthusiastically than other times. I began it during the Lib Dem leadership election in 2007, and my first post announced portentously - to the couple of people who saw it - that I was going to vote for Nick Clegg.

"I know him to be one of those few in the Lib Dems who recognise the power of new ideas in politics, who understand that the party desperately needs to have a renewed purpose," I wrote then, and I stand by it now.

But voting for Clegg as leader did not mean any lack of confidence in Chris Huhne. He has a series of absolutely vital achievements under his belt during his foreshortened political career. His cabinet struggles with his Conservative colleagues about the importance of investment will turn out to be hugely significant when the history of these years is written.

I remember talking to him at the special Birmingham conference to ratify the coalition in May 2010, and thinking that I had never seen someone look quite so alive - becoming a Lib Dem cabinet minister must have been surprise enough; I did not then know that he was in a new relationship too.

So the sequence of events which led to the courtroom yesterday is a human tragedy - and more than that. It is a reminder of how fickle fate can be, a kind of memento mori for all of us, which I am desperately trying to keep in perspective.

I watched Nick Clegg fielding questions at the Brighton conference over the weekend, and felt huge confidence in him - as he clearly feels in himself. I didn't agree with everything he said - the Funding for Lending scheme is not a success, and was never going to be (the banks are the wrong infrastructure, but that is another story). I felt secure in my own mind that we had made the right choice in 2007, but I recognise - as I'm sure he does too - how difficult it is to be part of any kind of ferment of new ideas when you are at the heart of government.

What is extraordinary to me is this. Back then, when we chose a leader between Clegg and Huhne - would anyone have believed it if we knew that, five years later, one of them would be deputy prime minister and the other would be in jail?

"I know him to be one of those few in the Lib Dems who recognise the power of new ideas in politics, who understand that the party desperately needs to have a renewed purpose," I wrote then, and I stand by it now.

But voting for Clegg as leader did not mean any lack of confidence in Chris Huhne. He has a series of absolutely vital achievements under his belt during his foreshortened political career. His cabinet struggles with his Conservative colleagues about the importance of investment will turn out to be hugely significant when the history of these years is written.

I remember talking to him at the special Birmingham conference to ratify the coalition in May 2010, and thinking that I had never seen someone look quite so alive - becoming a Lib Dem cabinet minister must have been surprise enough; I did not then know that he was in a new relationship too.

So the sequence of events which led to the courtroom yesterday is a human tragedy - and more than that. It is a reminder of how fickle fate can be, a kind of memento mori for all of us, which I am desperately trying to keep in perspective.

I watched Nick Clegg fielding questions at the Brighton conference over the weekend, and felt huge confidence in him - as he clearly feels in himself. I didn't agree with everything he said - the Funding for Lending scheme is not a success, and was never going to be (the banks are the wrong infrastructure, but that is another story). I felt secure in my own mind that we had made the right choice in 2007, but I recognise - as I'm sure he does too - how difficult it is to be part of any kind of ferment of new ideas when you are at the heart of government.

What is extraordinary to me is this. Back then, when we chose a leader between Clegg and Huhne - would anyone have believed it if we knew that, five years later, one of them would be deputy prime minister and the other would be in jail?

Published on March 12, 2013 03:11

March 11, 2013

Why we don't want to re-invent 1945

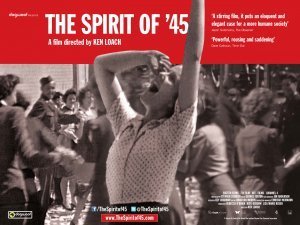

I found myself on

Start the Week

this morning with Ken Loach and others talking about class, and talking about his film Spirit of '45.

I found myself on

Start the Week

this morning with Ken Loach and others talking about class, and talking about his film Spirit of '45.I also talked about my forthcoming book about the squeezed middle, Broke, but let's leave that on one side for a moment.

Since watching the film last week, I have been struggling to articulate what I felt was wrong with the Attlee government and the post-war settlement that is given such heroic and emotional support in Ken Loach's film. The best I can come up with is this: those huge institutions created by Labour to slay Beveridge's Five Giants were not up to the job.

Oh yes, they slayed the giants, but the giants came back to life again - and still come back to life again every generation, and have to be slayed over and over again, and it costs that much more each time. That was not how they were designed and not what was expected - Beveridge expected the NHS and welfare state to get cheaper to run over time, not more expensive.

The trouble was that these institutions also disempowered people. They had their own agendas, their own elites and - more recently - their own dysfunctional targets hollowing them out. Beveridge warned that this would be the case as well, in his report Voluntary Action, and he was ignored.

Watching the Ealing film Passport to Pimlico recently, there is a hint of this too - someone shouts at the officials:

"We're sick and tired of your voice in this country - now shut up!" That sheds some light on why the Attlee government was voted out in 1951.

Ken Loach hinted at something similar, so I can't accuse him of this. But the idea that somehow the Labour creation was betrayed or destroyed by Mrs Thatcher, and we must look back to 1945 and do it all over again, is really nonsense. The truth is that these huge institutions carried the seeds of their own destruction. They carried the Thatcherite revolution within them, because they did not work - they disempowered, undermined communities, poured scorn on self-help, worshipped professionals, and never asked for anything back - which meant they failed to build community around them.

But how do you explain all that in about 30 seconds? Most of my attempts end up with me being pigeon-holed either as a conservative (that I want to sell off the welfare state) or that I am a socialist (I want to build it all again, just the same). I don't believe either of those. We need to somehow mould what we've got into something far more flexible and far more effective - and do it very fast.

That requires people who are capable of making relationships with the people they are trying to help - which is precisely the opposite direction the big welfare institutions have been going. It means the very opposite of economies of scale. Whatever it means, it certainly doesn't mean going back to 1945.

Published on March 11, 2013 08:11

March 10, 2013

Happy birthday, William Cobbett - we need you now

I'm very grateful to the King of the Lib Dem bloggers, Jonathan Calder, for reminding me that it is William Cobbett's 250th birthday - actually yesterday. But perhaps after a quarter of a millennium, being a day late doesn't matter.

I'm very grateful to the King of the Lib Dem bloggers, Jonathan Calder, for reminding me that it is William Cobbett's 250th birthday - actually yesterday. But perhaps after a quarter of a millennium, being a day late doesn't matter.Cobbett returned to England as a Tory, but the critical moment in his conversion to what I believe was a ferocious proto-Liberalism, came in 1805, a few months before Nelson’s historic destruction of Napoleon’s naval ambitions. He bought a farm outside the Hampshire village of Botley and immediately found himself campaigning against proposals to enclose nearby Horton Heath right from the start, despite the massive profits he would have made if he had fallen into line.

Having been offered, and refused, a share of the national debt as one of the placement he derided, he also took a second look at the writings of Thomas Paine, the great British libertarian he had condemned so roundly before. Once he had done so, he was particularly struck by what Paine had to say about the financial system and, from there, he slowly became aware of the scale of the bribery, money-lending and sinecures on offer around him. Pitt’s friend Henry Dundas, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was charged with using public money for private speculation. The army commander-in-chief, the Grand old Duke of York, was letting his mistress sell army commissions on his behalf.

This was what Cobbett came to know and condemn as The Thing – the great mountain of placemen and pensioners paid for by the struggling farmers and labourers of the nation.

The superstructure of The Thing, as he saw it, was the burgeoning financial services in London, the stockjobbers and speculators, making money out of money and leaching it out of productive agriculture. Still financed by the high Tories under Windham, Cobbett found himself slipping into the kind of campaigns launched in the previous century by Defoe and Swift, and echoed across the Atlanticby the anti-banking rhetoric of Jefferson himself.

Inspired by Paine, Cobbett suddenly regarded the nation he became famous by defending differently. It was ruled, not so much by a government – and certainly not by a king of doubtful sanity – but by a financial system, and one which had “drawn the real property of the nation into fewer hands … made land and agriculture objects of speculation ... in every part of the kingdom, moulded many farms into one … almost entirely extinguished the race of small farmers … we are daily advancing to the state in which there are but two classes of men, masters and abject dependents.”

Almost unwittingly, Cobbett was following the long agrarian tradition of deep scepticism about money, suspicion of banking and finance, and an implicit appeal to what was genuinely important. It was the ‘real property of the nation’, that Cobbett was defending. Not the stuff of fashion and instant wealth. Being in Hampshire also raised his awareness of the plight of ordinary labourers once the commons had been enclosed.

When he was campaigning to protect his own heath from enclosure, he ran across a Parliamentary report which estimated that there were a million paupers in England and Wales, a tenth of the population. He sent this investigation to Windham, the leader of the Country Tories, but it raised little interest. For the Tories, the problem of paupers was primarily that they were a threat to national security.

For Cobbett, it was the greed of middlemen and bourgeois speculators that was driving ordinary people from the land, which was their only guarantee of independence and subsistence. Those who remained were being squeezed by Londonfinanciers and establishment minions, between them sucking the available money in sinecures, pensions and taxes. This was The Thing.

What is extraordinary is how relevant this critique is today. The Thing, the corrosive hoovering up of the wealth of the nation by speculators, is at least as important as it was in Cobbett's day. Probably even more.

Published on March 10, 2013 10:21

March 9, 2013

Why economists can add but not subtract

More than a decade ago, I wrote a book called

The Tyranny of Numbers

, which was an early attempt to puncture a hole in the cult of statistics, evidence-based policy and the corrosion of intuition and common sense that goes with it.

It had a whiff of naivety about it, I admit. Of course there are times when a good bit of measurement can take a situation by surprise. You don't want to lose that option. But I was staggered recently, working in a government department at rather closer quarters than usual, to find how much the cult of measurement has progressed - almost no conversation seems possible without it being littered with statistics, some of them helpful, some of them really rather dodgy.

The great problem with this is that numbers look authoritative, but they tend to be attached to descriptions. The numbers look hard but they are chained inexorably to words, which are endlessly malleable. What looks so objective and certain is actually nothing of the kind.

Worse than that. The most important things in life are not actually measurable at all - disease and violence may be measurable, but health and love are not. You have to take measurements of something else and hope that they relate to each other - and usually they don't.

But of all the sins of statistics which we are lumbered with every day, really the bogus economic cost-benefit analysis takes the biscuit.

I thought of this earlier in the week when I was confronted with a suspect study commissioned by the pro-Heathrow lobby which claims that £8.5 billion will be lost if Heathrow isn't expanded.

Here the consultants at Oxford Economics have gone away and worked out what the potential spending power of visitors to Britain would be from China is Heathrow was expanded. That is all it is. But they seem to have ignored the disbenefits - the costs of expanding Heathrow in terms of health, destruction, climate change and pollution, and sleepless nights for those living in west London.

Would the UK actually be richer because of the money? No, because there are also costs involved and those haven't been factored in - because, for some reason, economists seem unable to do subtraction.

It was the same with the studies urging the government to end restrictions on supermarket opening hours, explaining how much extra earning there would be - but nothing about the costs at all.

GDP is the same: it adds up the goods but doesn't subtract the bads. Or as the economist Clifford Cobb and his colleagues put it in their 1994 article 'If the economy is up, why is America down?': "The nation's central measure of well being works like a calculating machine that adds but cannot subtract."

It is time someone called time on this nonsense. Time, in fact, for a Campaign for Real Knowledge, not hedged around with bogus cost-benefits and which is capable of describing the world as it really is. And to do that, numbers are really too much of a blunt instrument.

It had a whiff of naivety about it, I admit. Of course there are times when a good bit of measurement can take a situation by surprise. You don't want to lose that option. But I was staggered recently, working in a government department at rather closer quarters than usual, to find how much the cult of measurement has progressed - almost no conversation seems possible without it being littered with statistics, some of them helpful, some of them really rather dodgy.

The great problem with this is that numbers look authoritative, but they tend to be attached to descriptions. The numbers look hard but they are chained inexorably to words, which are endlessly malleable. What looks so objective and certain is actually nothing of the kind.

Worse than that. The most important things in life are not actually measurable at all - disease and violence may be measurable, but health and love are not. You have to take measurements of something else and hope that they relate to each other - and usually they don't.

But of all the sins of statistics which we are lumbered with every day, really the bogus economic cost-benefit analysis takes the biscuit.

I thought of this earlier in the week when I was confronted with a suspect study commissioned by the pro-Heathrow lobby which claims that £8.5 billion will be lost if Heathrow isn't expanded.

Here the consultants at Oxford Economics have gone away and worked out what the potential spending power of visitors to Britain would be from China is Heathrow was expanded. That is all it is. But they seem to have ignored the disbenefits - the costs of expanding Heathrow in terms of health, destruction, climate change and pollution, and sleepless nights for those living in west London.

Would the UK actually be richer because of the money? No, because there are also costs involved and those haven't been factored in - because, for some reason, economists seem unable to do subtraction.

It was the same with the studies urging the government to end restrictions on supermarket opening hours, explaining how much extra earning there would be - but nothing about the costs at all.

GDP is the same: it adds up the goods but doesn't subtract the bads. Or as the economist Clifford Cobb and his colleagues put it in their 1994 article 'If the economy is up, why is America down?': "The nation's central measure of well being works like a calculating machine that adds but cannot subtract."

It is time someone called time on this nonsense. Time, in fact, for a Campaign for Real Knowledge, not hedged around with bogus cost-benefits and which is capable of describing the world as it really is. And to do that, numbers are really too much of a blunt instrument.

Published on March 09, 2013 13:27

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.