David Boyle's Blog, page 82

May 7, 2013

Windmills, UKIP and growing things

There is something wonderfully life-enhancing about lying on grass, in my humble opinion. And that is what I did yesterday in the sunshine, on the top of the South Downs, overlooking the Solent, right next to Halnaker Mill.

There is something wonderfully life-enhancing about lying on grass, in my humble opinion. And that is what I did yesterday in the sunshine, on the top of the South Downs, overlooking the Solent, right next to Halnaker Mill.Halnaker Mill is in Sussex and was immortalised in a melancholic poem by Hilaire Belloc, who saw its dilapidation as a symbol of the ruin of English agriculture - and therefore England itself. But it isn't ruined now. It is nicely painted in white, and perfect for picnics, especially on a May Bank Holiday.

Belloc was not just bringing up a conservation issue here, and the usual English solutions to conservation problems would not have appealed to him.

There is a tendency for us to feel that, just because we have put up an information board, then somehow the heritage has been protected. Then we tend to add a second hand bookstall selling books about thatching, stuff about downland ways by H. J. Massingham and some rather elderly biographies of the Queen Mother. Et voila! Instant English heritage!

Actually, there isn't even an information board at Halnaker Mill and, in any case, Belloc's critique was much more fundamental.

There is a continuing, hidden tradition in English politics - it is particularly English - that regards agriculture as part of the national soul. It is related to Liberalism (Belloc was a Liberal MP) but it is not quite the same. It is melancholic where Liberalism was optimistic, rural where Liberalism was urban and Anglo-Catholic where Liberalism was primarily non-conformist. But there is a relationship because it is about how communities can sustain themselves in some kind of economic and political freedom.

It is important in Liberal Party history too because the agrarian radicals tended to go with Chamberlain and Collings in the split with the Liberal Unionists. They wanted to spread the ownership of land in the great Edwardian land debate when the mainstream Liberals wanted to tax it. I've written more about it in my ebook On the Eighth Day God Created Allotments (only £1.99!).

The agrarians were also sceptical of free trade when it came to agriculture. This is what the great Liberal Jesse Collings said a century ago:

“They say the land will not produce now. Has it lost its character? Take one article: how is it we buy every year £5,000,000 worth of cheese from the foreigner? Can England not produce this? How is it we purchase from £12,000,000 to £14,000,000 worth of butter? Is England not a butter producing country.”

It sounds modern, doesn't it. So I don't think this is just political archaeology, especially when we have a different kind of nationalism breathing down our necks in the shape of UKIP. The agrarian radicals can teach us something here which can help::

1. There need not be a rigid split any more between consumers and producers. This is what the futurist Alvin Toffler calls the new prosumers, and it provides a way that people can be more pro-active earning themselves the means to live - which underpins our freedom as well.

2. Communities and neighbourhoods could, and should, develop ways that they can kick-start their struggling local economies using existing local resources - wasted people, wasted land, wasted stuff - rather than indulging in the disempowering wait for central government or outside investors to bail them out.

3. The right to grow things for local consumption, as shown in places like Todmorden, is a way of revitalising much more than just the local economy. It can underpin local life in a whole variety of ways. See for example what is happening with the 'patchwork farm' near where I live in urban Crystal Palace.

So Belloc and his Distributists were right, at least to that extent, and we need to re-learn some of those political lessons if we are going to hammer out a non-technocratic approach to national revival that can have some populist appeal.

So in honour of this thought, and of Belloc - who is one of my heroes (I know, I know, he had major faults) - and in honour of the bank holiday just gone, here is Belloc's poem 'Ha'naker Mill':

Sally is gone that was so kindly, Sally is gone from Ha'nacker Hill And the Briar grows ever since then so blindly; And ever since then the clapper is still... And the sweeps have fallen from Ha'nacker Mill.

Ha'nacker Hill is in Desolation: Ruin a-top and a field unploughed. And Spirits that call on a fallen nation, Spirits that loved her calling aloud, Spirits abroad in a windy cloud.

Spirits that call and no one answers -- Ha'nacker's down and England's done. Wind and Thistle for pipe and dancers, And never a ploughman under the Sun: Never a ploughman. Never a one.

I am glad to say that Halnaker is no longer in desolation. But the basic problem remains: the failures of English local production. Never a ploughman, unfortunately.

Writing this post has made me think about how it might be possible to construct a Liberal populism and I shall return to this theme!

Published on May 07, 2013 02:14

May 6, 2013

So what did kill off British industry all those years ago?

Imagine you wrote a book about the threat to the middle classes and implied that one person in particular deserves at least some of the blame - then the Sunday Times handed your book to that man's son to review. What would you feel? Nervous?

Imagine you wrote a book about the threat to the middle classes and implied that one person in particular deserves at least some of the blame - then the Sunday Times handed your book to that man's son to review. What would you feel? Nervous?The prospect of reading Dominic Lawson's review of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes? nearly prevented me from reading the papers at all this morning. But, in the event, Dominic is highly professional and I needn't have worried:

"Boyle's call to bourgeois arms ... has a pace and passion that elude most chroniclers of economic change."

"... engagingly sensitive to the sentiments of what is sometimes called 'middle England'."

For those sentences, I'm prepared to forgive the Lawson family almost anything, though he did say I ruined the second one by 'hyperbole'. Yet he had clearly read the book carefully, and you can't ask for more than that from a reviewer.

There are three areas where he fundamentally disagrees with me though. He claims that house prices are more affordable than they have been for a generation outside south east England. Perhaps so, but I don't see why it is acceptable that the middle classes should be excluded from living in the south east either - renting or working - in the next generation.

He also ridiculed the idea that people sometimes worry (I certainly do), when they are in confined spaces, whether their children are on the autistic spectrum after all, as they bang into furniture and break small ornaments. Dominic Lawson says this idea "takes the organic biscuit". Perhaps he has never had to look after children in a confined space.

But what I found fascinating was that he disagreed that the discovery of North Sea Oil had destroyed UK manufacturing industry. What was it then?

I don't believe the rhetoric from the left that Margaret Thatcher's ministers somehow roamed the nation slashing and burning any factories they might find. Certainly, British industry was staggeringly under-invested and badly managed by the 1970s, but what was it that gave the coup de grace?

The answer was that, to the surprise of Nigel Lawson, Geoffrey Howe and their team, ending exchange controls in 1979 did not lead to a sinking pound. The value of the pound just kept on rising, because it was now a petro-currency. That was what brought to a juddering halt the continued industrial development of the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. Because nobody could afford our products.

There has been some manufacturing recovery over the past generation, but the swathes of former industrial land across the Midlands and the North, still lying empty, is testament to the disaster.

Speaking of which, I was delighted recently to find myself on the fourth floor of the Science Museum to find it completely untouched since I was last there - admiring the ship models - at the age of twelve or so. And pride of place has to go to their huge model of London Docks with the label: 'The busiest port in the world'. No mention of the Docklands Development Corporation, Canary Wharf, yuppies, the Dome or any of the rest.

It really is extraordinary, and somehow life-enhancing, to find that the last four decades has passed them by.

It set me wondering. Could London Docks have been saved by containerisation, or investment, or modern labour relations? Probably not, and their closure is some evidence on Dominic Lawson's side. It was the disastrous 1970s that did for the Docks, just as the same years undermined the foundations of British industry. But it was the pound, turbo-charged by North Sea Oil which struck the final blow - not to London Docks, but to so much of the rest.

Published on May 06, 2013 01:14

May 5, 2013

Don't tell me, it's the same old useless RBS?

Gosh, I'm getting bored of UKIP already. Nigel Farage's face on the front of all the papers yesterday was quite enough for me. I don't think I'll blog about them again, especially as I got a slightly worrying email after last time which said: "@UKIP is following you on Twitter".

So instead I think it is time I blogged about banks. Can I explain for a moment why my heart sank as much as it did when I heard the announcement that RBS had returned to profitability and would be privatised within a year? The giveaway line was from chief executive Stephen Hester that the bank would be "looking much more like a normal bank next year".

Here is the problem in stark technicolour. 'Normal banks' in the UK context are wholly dysfunctional. With one exception, the big banks have no local lending infrastructure, no lending expertise at local level, no managers allowed to take decisions, and consequently our vital small business sector is struggling along starved of the finance they need.

I don't know, and can't find out, what the profile of RBS' recent lending is, but I expect it is much the same as the other dysfunctional banks - 70 per cent of it going into property deals, because that is all they can deal with (and they would also rather like to recreate the conditions for the last bubble).

Hester seems not to understand the basic problem in the story in today's papers, where he claims that RBS has £20bn that nobody will borrow. The problem is they have no local infrastructure for analysing small businesses, and continue to charge outrageous rates of interest, and then wonder why the small businesses don't ask.

I am not complaining about the principle or the means of privatising the bank. It could still be given away to every member of the population, as set out by Lib Dem policy-makers. What really worries me is that it will be returned to the private sector exactly as it was before, when we desperately need a local and regional, and above all responsive, banking sector and RBS could have provided the basis for that.

We need what they have in America and Europe but we don't have: a diverse banking system capable of providing for Britain's struggle entrepreneurs. Instead RBS is going to stay its old dysfunctional and useless self, except in the private sector.

I refreshed my memory of the coalition agreement on this point, and this is what I found:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals for robust action to tackle unacceptable bonuses in the financial services sector; in developing these proposals, we will ensure they are effective in reducing risk."

My impression of the 'robust action' to reduce banking bonuses was that it involved battering Brussels when they wanted to reduce them. Then there was this passage:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals to foster diversity, promote mutuals and create a more competitive banking industry."

Yes, the new regulator now has to bear in mind the diversity of the banking system, but what else has the coalition done to foster diversity, let alone promote mutuals so far? It isn't possible, is it, that the coalition will leave office without having introduced any 'detailed proposals' at all? And without doing that, how can they possibly push forward that other critical coalition objective: re-balancing the economy?

So instead I think it is time I blogged about banks. Can I explain for a moment why my heart sank as much as it did when I heard the announcement that RBS had returned to profitability and would be privatised within a year? The giveaway line was from chief executive Stephen Hester that the bank would be "looking much more like a normal bank next year".

Here is the problem in stark technicolour. 'Normal banks' in the UK context are wholly dysfunctional. With one exception, the big banks have no local lending infrastructure, no lending expertise at local level, no managers allowed to take decisions, and consequently our vital small business sector is struggling along starved of the finance they need.

I don't know, and can't find out, what the profile of RBS' recent lending is, but I expect it is much the same as the other dysfunctional banks - 70 per cent of it going into property deals, because that is all they can deal with (and they would also rather like to recreate the conditions for the last bubble).

Hester seems not to understand the basic problem in the story in today's papers, where he claims that RBS has £20bn that nobody will borrow. The problem is they have no local infrastructure for analysing small businesses, and continue to charge outrageous rates of interest, and then wonder why the small businesses don't ask.

I am not complaining about the principle or the means of privatising the bank. It could still be given away to every member of the population, as set out by Lib Dem policy-makers. What really worries me is that it will be returned to the private sector exactly as it was before, when we desperately need a local and regional, and above all responsive, banking sector and RBS could have provided the basis for that.

We need what they have in America and Europe but we don't have: a diverse banking system capable of providing for Britain's struggle entrepreneurs. Instead RBS is going to stay its old dysfunctional and useless self, except in the private sector.

I refreshed my memory of the coalition agreement on this point, and this is what I found:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals for robust action to tackle unacceptable bonuses in the financial services sector; in developing these proposals, we will ensure they are effective in reducing risk."

My impression of the 'robust action' to reduce banking bonuses was that it involved battering Brussels when they wanted to reduce them. Then there was this passage:

"We agree to bring forward detailed proposals to foster diversity, promote mutuals and create a more competitive banking industry."

Yes, the new regulator now has to bear in mind the diversity of the banking system, but what else has the coalition done to foster diversity, let alone promote mutuals so far? It isn't possible, is it, that the coalition will leave office without having introduced any 'detailed proposals' at all? And without doing that, how can they possibly push forward that other critical coalition objective: re-balancing the economy?

Published on May 05, 2013 08:22

May 4, 2013

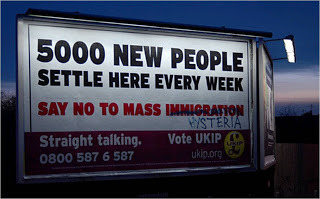

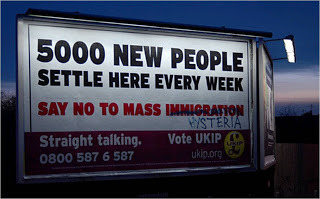

Tough on the causes of UKIP

I have been contemplating the strange thought that a quarter of the population voted for UKIP and Nigel Farage's slightly dodgy populists - the same proportion of the vote that the Labour Party won in 1983 (also, as you may remember, the Liberal-SDP Alliance, those were the days...)

This doesn't mean that Farage is going to be prime minister or that they will win any seats at the next general election - I suspect UKIP are about as far from being able to 'target' seats as it is possible to be. But it is worrying, and - if Kenneth Clarke calls them clowns a few more times - they might even win more votes.

This doesn't mean that Farage is going to be prime minister or that they will win any seats at the next general election - I suspect UKIP are about as far from being able to 'target' seats as it is possible to be. But it is worrying, and - if Kenneth Clarke calls them clowns a few more times - they might even win more votes.

It is worrying because there is a grain of truth in Farage's claim that UKIP are outsiders, battering on the doors of the establishment from the real world. Populism is not a bad thing in itself - only when it is used to drum up hatred - but the political establishment would prefer to drink their own blood rather than drop their technocratic utilitarianism. This is a potent fertiliser for populists like UKIP.

But the real reason why we are experiencing this populist uprising is the pressure on the middle classes. This is what I wrote at the end of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes?, published last week. It is about the political implications of the impossible economic pressures that are building up on the middle classes:

"Karl Marx has long been dismissed for his predictions that the bourgeoisie would eventually disappear and usher in the new revolution. It never happened. Quite the reverse, the bourgeoisie and petit bourgeoisie burgeoned in size, bought their own homes and started reading Country Homes and Interiors. But what if Marx’s prediction was correct, but just a little delayed, and capitalism were to culminate in the proletarianization of the middle classes after all? What would happen then? Some kind of revolution or, as Fukuyama predicts, some kind of populist uprising from the right? The latter seems most likely at the moment, given that most of Western Europe is struggling to survive a financial crisis brought on, predictably, by the tight constraints of the euro. A thriving middle class would provide an inoculation against that kind of upheaval, but if they are not thriving – what then? Some of the peculiar backward-looking political movements emerging on both sides of the Atlantic may be symptoms of the busting of the middle classes, including the Tea Party in the USA and UKIP in the UK. When the bottom seems to fall out of the middle-class economy, these kind of embarrassingly conservative organizations seem to emerge. We can only imagine the political fallout if these trends continue."

They may not break through this time. I suspect UKIP will unravel in a series of embarrassing revelations. But there will be others, even less civilised.

And they will be the direct result of the proletarianisation of the middle classes by the new elite. And of people not being able to afford to live in the area they grew up in. Or promising to re-balance the economy, but selling off dysfunctional RBS exactly as it was before. Or prioritising the protection of bankers' bonuses in Brussels negotiations. And so on, and so on.

This doesn't mean that Farage is going to be prime minister or that they will win any seats at the next general election - I suspect UKIP are about as far from being able to 'target' seats as it is possible to be. But it is worrying, and - if Kenneth Clarke calls them clowns a few more times - they might even win more votes.

This doesn't mean that Farage is going to be prime minister or that they will win any seats at the next general election - I suspect UKIP are about as far from being able to 'target' seats as it is possible to be. But it is worrying, and - if Kenneth Clarke calls them clowns a few more times - they might even win more votes.It is worrying because there is a grain of truth in Farage's claim that UKIP are outsiders, battering on the doors of the establishment from the real world. Populism is not a bad thing in itself - only when it is used to drum up hatred - but the political establishment would prefer to drink their own blood rather than drop their technocratic utilitarianism. This is a potent fertiliser for populists like UKIP.

But the real reason why we are experiencing this populist uprising is the pressure on the middle classes. This is what I wrote at the end of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes?, published last week. It is about the political implications of the impossible economic pressures that are building up on the middle classes:

"Karl Marx has long been dismissed for his predictions that the bourgeoisie would eventually disappear and usher in the new revolution. It never happened. Quite the reverse, the bourgeoisie and petit bourgeoisie burgeoned in size, bought their own homes and started reading Country Homes and Interiors. But what if Marx’s prediction was correct, but just a little delayed, and capitalism were to culminate in the proletarianization of the middle classes after all? What would happen then? Some kind of revolution or, as Fukuyama predicts, some kind of populist uprising from the right? The latter seems most likely at the moment, given that most of Western Europe is struggling to survive a financial crisis brought on, predictably, by the tight constraints of the euro. A thriving middle class would provide an inoculation against that kind of upheaval, but if they are not thriving – what then? Some of the peculiar backward-looking political movements emerging on both sides of the Atlantic may be symptoms of the busting of the middle classes, including the Tea Party in the USA and UKIP in the UK. When the bottom seems to fall out of the middle-class economy, these kind of embarrassingly conservative organizations seem to emerge. We can only imagine the political fallout if these trends continue."

They may not break through this time. I suspect UKIP will unravel in a series of embarrassing revelations. But there will be others, even less civilised.

And they will be the direct result of the proletarianisation of the middle classes by the new elite. And of people not being able to afford to live in the area they grew up in. Or promising to re-balance the economy, but selling off dysfunctional RBS exactly as it was before. Or prioritising the protection of bankers' bonuses in Brussels negotiations. And so on, and so on.

Published on May 04, 2013 02:09

May 3, 2013

Vanessa Feltz made me think

I spent the hour between 11 am and 12 noon yesterday being grilled by Vanessa Feltz (from 2.03) live and on air on BBC London, with occasional contributions from callers. The subject: the middle classes. The occasion: well, the publication of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes?

As the hour rushed by, I began to get the hang of not listening too closely to Vanessa's cascade of words in case it made me forget what I was about to say. But, do you know, the whole experience made me think.

I have been arguing all this time that the middle classes need to exist, not because they somehow deserve privileges, but because everyone needs the chance of some space in their lives - for culture, education, leisure. And since the fate that overwhelmed the working classes now awaits the middle classes, that space is about to be out of reach for all of us - life will be just too insecure.

But is it actually about the space for leisure?

Vanessa pointed out to me, somewhat forcibly, that she wakes up every morning to go to work at 4am. It is true that I also work the WHOLE time, much to the despair of my family.

But there is a big difference. We both love our work. I am able to work for very little money on subjects that inspire me, simply because I bought a house back in 1986 - so my mortgage repayments are less than £300 a month. If I had bought in 1996 or, even worse, 2006 then my mortgage repayments (or rent) would be so high that I could not do the work I love.

That is the real issue, and it isn't about class - despite the title of my book - it is about whether we will in future have the opportunity to do the work we love. Or whether we will be forced into indentured servitude just to get a roof over our heads.

That's the issue. I sometimes think, as I cycle to the station, that I am the luckiest person in the whole of London - because I have a low enough mortgage to be my own boss and to write about the things that thrill me.

Vanessa asked me what career advice I would give my children. The career advice I always give is that, if you do what thrills you the most, the money tends to follow. That is what I will tell them.

I would like my children to have that opportunity to put that advice into practice, certainly by the time they are my age in the 2050s. I think it is extremely unlikely that they will be able to.

Published on May 03, 2013 01:42

May 2, 2013

Mad Candidates Disease and how to recognise it

Let's spare a thought today for all our candidates facing their moment of truth in the local elections - and not just our candidates (by which I refer of course to the Lib Dems), but all candidates everywhere. Even maybe the 'clowns'.

Think of them because, however level-headed they are - however sensible and charming they are in other aspects of their lives, or were before signing their election papers - they are still susceptible to worrying signs of Mad Candidates Disease.

I haven't been a candidate myself since 2001 (how are you, Regents Park and Kensington North?), but even I fell victim. The good news is that the symptoms tend to recede after the count, and everything can return to normal. There is hope.

But forewarned is forearmed, and it is worth knowing what the symptoms are so that they can be tackled. Probably the key signs that you are suffering from Mad Candidates Disease are a dull and obsessive look in the eye, brought on by lack of sleep and single-minded determination for something you can't quite put your finger on. But also watch out for the following:

1. Your conversation is dull, repetitive and paranoid to the point of fixation. So are your dreams.

2. Despite all evidence to the contrary, despite the fact that nobody from your party has ever won in your area - and despite the fact that you have delivered no leaflets - there is still a small part of you that thinks, well, we could pull it off.

3. Every event, fortunate and unfortunate - from your wife's cancer to your forthcoming lobotomy - is interpreted by you solely in terms of its impact on your own electability.

There are more serious symptoms for prolonged sufferers, but let's draw a veil over these.

How do I know all this when I haven't even stood for election for twelve long years? Well, because I write books and am therefore prone to a very similar condition called Mad Authors Disease. Symptoms are much the same. Despite all evidence to the contrary, despite the fact that your book has failed to make it into Waterstone's and is trailing on Amazon - and despite the fact that there have been no reviews or publicity of any kind - there is still a small part of you that thinks, well, it could be a bestseller.

I may not have Mad Candidates Disease, but I have suffered from Mad Authors Disease for more years now than I care to remember. There is a cure, but it is worse than the disease itself. It is to stop writing books.

Think of them because, however level-headed they are - however sensible and charming they are in other aspects of their lives, or were before signing their election papers - they are still susceptible to worrying signs of Mad Candidates Disease.

I haven't been a candidate myself since 2001 (how are you, Regents Park and Kensington North?), but even I fell victim. The good news is that the symptoms tend to recede after the count, and everything can return to normal. There is hope.

But forewarned is forearmed, and it is worth knowing what the symptoms are so that they can be tackled. Probably the key signs that you are suffering from Mad Candidates Disease are a dull and obsessive look in the eye, brought on by lack of sleep and single-minded determination for something you can't quite put your finger on. But also watch out for the following:

1. Your conversation is dull, repetitive and paranoid to the point of fixation. So are your dreams.

2. Despite all evidence to the contrary, despite the fact that nobody from your party has ever won in your area - and despite the fact that you have delivered no leaflets - there is still a small part of you that thinks, well, we could pull it off.

3. Every event, fortunate and unfortunate - from your wife's cancer to your forthcoming lobotomy - is interpreted by you solely in terms of its impact on your own electability.

There are more serious symptoms for prolonged sufferers, but let's draw a veil over these.

How do I know all this when I haven't even stood for election for twelve long years? Well, because I write books and am therefore prone to a very similar condition called Mad Authors Disease. Symptoms are much the same. Despite all evidence to the contrary, despite the fact that your book has failed to make it into Waterstone's and is trailing on Amazon - and despite the fact that there have been no reviews or publicity of any kind - there is still a small part of you that thinks, well, it could be a bestseller.

I may not have Mad Candidates Disease, but I have suffered from Mad Authors Disease for more years now than I care to remember. There is a cure, but it is worse than the disease itself. It is to stop writing books.

Published on May 02, 2013 01:14

May 1, 2013

The sheer costs of nuclear malfunction

It is rather strange, but the present crisis at the doomed Japanese nuclear plant at Fukushima seems to have gone unreported in the UK press.

It is rather strange, but the present crisis at the doomed Japanese nuclear plant at Fukushima seems to have gone unreported in the UK press.Groundwater is seeming into the stricken reactors at the rate of 75 gallons a minute, where it gets seriously contaminated and has to be stored in great vats on site. It is pouring in at such a rate that the reactor operators are in the process of felling the next door forest to make more space for storing contaminated water.

When nuclear power plants go wrong, they really do go wrong.

Which gives me the opportunity of repeating what I once rather immodestly called Boyle's Law - that decentralised renewable energy is bound to get cheaper and nuclear energy is bound to get more expensive.

This does not require a Fukushima-style meltdown to happen in the UK, or anything like it. Every time a new risk is diagnosed, or a new terrorist group appears to want to get hold of plutonium, the costs will rise - and potentially by billions, certainly millions.

That is why it is absolutely vital that the full costs of nuclear energy do not fall on taxpayers. It is now exactly three years since the special Lib Dem conference in Birmingham to ratify the coalition, where Chris Huhne used the phrase: "Read my lips; no nuclear subsidies".

A lot has changed since then, and not just to Chris Huhne. The government is desperate to sign a nuclear contract and, although they will be hidden in guaranteed prices, the subsidies will unfortunately be there - and the endless nuclear waste without a solution represents another unfunded cost. So does the increasingly vital nuclear security costs.

But the most important basis for this reiteration of Boyle's Law is that breakdowns in complex, centralised energy systems are very expensive and very serious. Breakdowns in simple, decentralised systems are irritating but easily put right.

These issues may turn out to be much more important politically than they seem, because I believe we are on the verge of a whole new wave of militant environmentalism, angry at plans for local fracking and furious at any local manifestation of the nuclear industry. Not because of climate change or any green theoreticals, but simply because people will do almost anything if they think the health of their children is threatened.

And, despite my calm and rational exterior, I know whose side I am likely to be on.

Published on May 01, 2013 01:54

April 29, 2013

The difference between catching criminals and preventing crime? About 30 seconds

What is the difference between catching criminals and preventing crime, the distinction set out by the chief inspector of constabulary, Tom Winsor, today?

The reason I ask is that he didn't seem that sure himself. Prevention seemed to be about catching criminals with new technology and getting the public on board to help you. Yes, but...

The truth is that, when you look at it like this - apparently a mission to change everything just a little bit - the distinction between preventing crime and catching criminals is the 30 seconds or so between thinking about it and doing the deed.

I'm always a little sceptical when I hear that effectiveness is going to be enhanced by new technology. It isn't impossible. It is just that, in practice, it rarely is. Often it gets worse. In fact, the famous story of the beginnings of the concept of co-production in public services was about precisely this.

The great sociologist Elinor Ostrom was asked by the Chicago police in 1975 to help them find out why crime was rising. Why was it that, when they took their police off the beat and into patrol cars – and gave them a whole range of hi-tech equipment that can help them cover a larger area more effectively – why then did the crime rate go up?

This isn’t just a question confined to the police. It lies at the heart of why public services become less effective on the ground as they become less personal and more centralised.

Elinor Ostrom’s team decided that the reason was because that all-important link with the public was being broken. When the police were in their cars, the public seemed to feel that their intelligence, support, and help were no longer needed. She called this joint endeavour that lies at the heart of all professional work 'co-production' and technology can sometimes get in its way - because it makes frontline professionals forget the public altogether.

Winsor was absolutely right about that much. He was also right about three other aspects of all this.

First, the target culture has been staggeringly wasteful of police resources. If you don't believe me, read the extraordinary revelations of the police blogger Inspector Guilfoyle, who has blogged about precisely this, explaining absolutely correctly that:

"as you go down the levels of hierarchical organisations, the obsession with hard numerical targets intensifies. By the time you get to the front line, believe me, people DO pay A LOT of attention to the actual targets. The targets then become a focus for activity, driving behaviour and creating a culture of unhealthy internalised competition and individual blame."

Incidentally, a brilliant blog called Systems Thinking for Girls has set out quite clearly why targets lock in failure and it is seriously worth a read.

Second, part of the prevention issue for the police is what the systems thinker John Seddon calls 'failure demand'. It is the failures of other public services, notably in mental health, that really waste police money.

Third, Winsor's rhetoric is absolutely right. The future of policing is indeed prevention - it is the future of all public services - but it requires a completely different institution to make that possible, more outward-facing, dedicated to very local alliances in neighbourhoods, and street-by-street attention to detail, and to reaching out beyond the boundaries of police work.

And, above all, it means working with people - not just getting information from them via technological gizmos - but setting up the local institutions capable of knitting society back together around the police.

If we want to save our public service tradition - and we do - then prevention is the only way forward, the only way of generating the savings we need at the same time as turbo-charging the effectiveness of services. But to make it work, our institutions will be completely different.

Published on April 29, 2013 23:29

Why we need a pupil premium league table

Bated breath isn't quite the right description, but I am patiently waiting for the government's official response to the so-called Boyle Review, the independent review I led into barriers to choice in public services.

More on that later (I hope).

But one of the areas I looked at in the review, and returned to in my new book Broke , is the difficulties parents have getting the information they want from school league tables.

The problem with league tables and targets is that they tell you a great deal about how institutions conform to what the government wants, and not much about the things that might interest you - in this case, bullying, atmosphere, creativity, friendliness.

There is also scepticism about the official data in education, both among parents and professionals. People can see, from their own experience, that league tables can be manipulated by schools – to the extent that schools higher in the league tables may be there partly because they have taught too closely to the tests, perhaps at the expense of a more rounded education.

There is also a difficulty about pupil premium pupils, because the efforts each school makes to help them improve gets lost in their overall league table position. And it was this that I focused on, and news a few days ago shows that Lib Dem education minister David Laws is also thinking along these lines. I don't know if this is because of my report, and don't really mind: I'm glad he is.

The pupil premium is a Lib Dem idea and it is supposed to work in two ways - by providing extra money which schools can spend on the pupils who need it most, and by encouraging good schools to take on more pupil premium (free school meal) pupils.

The practical problem with the second of these is that league tables get in the way. Schools are now able to change their admissions policies to include more free school meal pupils, but have no real incentive apart from the value of the pupil premium to compensate them for the extra cost - and the danger to their league table positions.

The pupil premium may provide some of that extra power to disadvantaged applicants; equally it may encourage the poorer performing schools to expand faster, given that they have more free school meal pupils. They get the bulk of the resources.

So there is a danger of a gulf opening up between successful, smaller schools and the increasingly large-scale institutions that cater for the rest of the population, which can give that much less individual attention. The true believers in competition believe that the good schools must expand, but the truth is that there are so many constrains on this that it would be silly to rely on it happening.

My answer is that there needs to be a league table specifically to show the performance of pupil premium pupils. To make this visible, you have to challenge the false 'bottom line' given by the existing league tables. Otherwise the position on the old league tables is an extremely powerful counter-pressure on schools not to risk varying the social balance of their intake.

Now, I've no idea whether this is what led David Laws to the rather shocking discovery that he made, but it is fascinating nonetheless.

There is a 25 percentage point gap between the achievements of pupil premium pupils and the rest. There may be socio-economic reasons for this, though I doubt it. But what is absolutely indefensible is that the gap is often wider in the wealthier areas than it is in the poorer areas. Buckinghamshire, Wiltshire, Surrey, Hampshire all have much wider gaps.

So I'm glad that Laws will be writing to specific schools to ask where they are spending their pupil premium money, and has promised that a big gap between rich and poor will threaten 'outstanding' status. I hope he will also do what I suggested, and launch a parallel league table just for pupil premium pupils.

Because the best way to challenge over-powerful and rather unhelpful bottom lines is to challenge them with other perspectives.

More on that later (I hope).

But one of the areas I looked at in the review, and returned to in my new book Broke , is the difficulties parents have getting the information they want from school league tables.

The problem with league tables and targets is that they tell you a great deal about how institutions conform to what the government wants, and not much about the things that might interest you - in this case, bullying, atmosphere, creativity, friendliness.

There is also scepticism about the official data in education, both among parents and professionals. People can see, from their own experience, that league tables can be manipulated by schools – to the extent that schools higher in the league tables may be there partly because they have taught too closely to the tests, perhaps at the expense of a more rounded education.

There is also a difficulty about pupil premium pupils, because the efforts each school makes to help them improve gets lost in their overall league table position. And it was this that I focused on, and news a few days ago shows that Lib Dem education minister David Laws is also thinking along these lines. I don't know if this is because of my report, and don't really mind: I'm glad he is.

The pupil premium is a Lib Dem idea and it is supposed to work in two ways - by providing extra money which schools can spend on the pupils who need it most, and by encouraging good schools to take on more pupil premium (free school meal) pupils.

The practical problem with the second of these is that league tables get in the way. Schools are now able to change their admissions policies to include more free school meal pupils, but have no real incentive apart from the value of the pupil premium to compensate them for the extra cost - and the danger to their league table positions.

The pupil premium may provide some of that extra power to disadvantaged applicants; equally it may encourage the poorer performing schools to expand faster, given that they have more free school meal pupils. They get the bulk of the resources.

So there is a danger of a gulf opening up between successful, smaller schools and the increasingly large-scale institutions that cater for the rest of the population, which can give that much less individual attention. The true believers in competition believe that the good schools must expand, but the truth is that there are so many constrains on this that it would be silly to rely on it happening.

My answer is that there needs to be a league table specifically to show the performance of pupil premium pupils. To make this visible, you have to challenge the false 'bottom line' given by the existing league tables. Otherwise the position on the old league tables is an extremely powerful counter-pressure on schools not to risk varying the social balance of their intake.

Now, I've no idea whether this is what led David Laws to the rather shocking discovery that he made, but it is fascinating nonetheless.

There is a 25 percentage point gap between the achievements of pupil premium pupils and the rest. There may be socio-economic reasons for this, though I doubt it. But what is absolutely indefensible is that the gap is often wider in the wealthier areas than it is in the poorer areas. Buckinghamshire, Wiltshire, Surrey, Hampshire all have much wider gaps.

So I'm glad that Laws will be writing to specific schools to ask where they are spending their pupil premium money, and has promised that a big gap between rich and poor will threaten 'outstanding' status. I hope he will also do what I suggested, and launch a parallel league table just for pupil premium pupils.

Because the best way to challenge over-powerful and rather unhelpful bottom lines is to challenge them with other perspectives.

Published on April 29, 2013 01:39

April 28, 2013

Vigilant against the post-human future

Artificial moons, 'geriatiric robots' designed to listen to old people, vats for growing chicken wings - all of these have been predicted in recent decades. None have happened quite like that. They rarely do.

Artificial moons, 'geriatiric robots' designed to listen to old people, vats for growing chicken wings - all of these have been predicted in recent decades. None have happened quite like that. They rarely do.This is partly because many elements of the technological futures the big corporations want are actually highly unpleasant or ineffective for everyone else. And partly because, compared to a century ago - when motor cars, cinematography, submarines, planes were developing so fast - our own technology has actually slowed to a snail's pace. I've been travelling on jumbo jets now for 40 years.

I know that isn't the conventional view, but I can only apologise for seeing things differently.

But there is one insidious corporate myth which is instantly recognisable. And there it was again in the Sunday Times this morning, quoted in a review of the new book The New Digital Age, co-authored by Eric Schmidt, chairman of the famous tax-avoiding corporation Google (not online)

"The online experience [will be] as real as real life, and perhaps even better."

The review was by the one person who has most effectively punctured this kind of corporate yearning, Bryan Appleyard, whose own book The Brain is Wider than the Sky , explains how the digital world is conspiring to reduce human capabilities in order to show how digital versions are somehow equal or superior. I can't say I've actually read Schmidt's book ("to read it would be to condone it"; F. R. Leavis), so perhaps I shouldn't comment until I have - but this phrase 'better than real' is so interesting, I can't help it.

It was a phrase pinpointed as belonging particularly to California by Umberto Eco in an essay in 1996 called Travels in Hyper-reality. When I was writing my book Authenticity, there it was again - the idea pedalled by Ray Kurzweil and other virtual reality cheerleaders that virtual sex will be, you guessed it, 'better than the real thing'.

The idea that there is something imperfect about the human spirit that makes it so successful is beyond them. So is the idea that it is the very imperfections in a human body that makes sex exciting. The diversity of human thought makes progress possible.

This is how I put it in my book The Age to Come:

"The post-modern advocate of artificial intelligence Ray Kurzweil suggests that the first artificial brain will be developed by 2029. The simplest computer has long since exceeded the memory and calculating skills of the cleverest human being. The computer Deep Blue beat the chess champion Gary Kasparov in 1995, it was a formative moment for the age that is to come. Because the challenge is now to set out what it is that human beings can do which no machine ever can – they can create, they can love and they can care."

They can do this in a way that works and fulfils, unlike the geriatric robot. They can also teach and heal better than the virtual teachers and doctors the corporate world wants, because they can make relationships.

Bryan Appleyard points out that the endorsements of Schmidt's book by Branson, Blair and Clinton demonstrate that his book is the direction the establishment wants to go. Our problem, it seems to me, is that it is such a narrow future, such an ineffective one, as well as such an isolated and tyrannical one. The post-human future is shiny, perfect and owned by the tax avoiders. We should be extremely suspicious of it.

Published on April 28, 2013 10:55

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.