David Boyle's Blog, page 79

June 10, 2013

Globalisation isn't happening

I spent last weekend in the Derbyshire Dales where my mother was brought up, and it had a dreamlike quality which I had forgotten.

Wandering through Bakewell in the sunshine also reminded me of one of the fundamental truths of globalisation – we are living in what is paradoxically a decreasingly globalised world.

I don’t think this just because I spend more time in Paris, Brussels or New York than I do north of Watford. Or just that I go to Edinburgh, Leeds or Manchester but not the swathes of the nation in between.

I isn’t just because a rare visit to Middlesborough, or even Harrogate, feels like a different country to south London. Its voices, faces, language and culture seem different, perhaps because they are different.

No, I’m confirmed in the sense that globalisation is a fantasy by the results of the 2001 census which found that half of us in the UK, and rising, live within 30 minutes of where we were born.

That is also about needing to be near free childcare because both partners of most couples need to work now to pay the mortgage or rent. They need to be near their parents. But it isn’t globalisation.

What I did see in the well-dressing at Ashford-in-the-Water, where we stayed, was a ‘children’s well’ dressed to celebrate 30 years of the Disney Channel. Now, that is globalisation, and here is the difference: because globalisation is not the same as Liberal internationalism.

Globalisation is about brands monoculture and monopoly. Internationalism is about diversity.

Globalisation is about widening gaps between rich and poor, centre and periphery, urban and rural. Internationalism is about closing the gap.

Globalisation is about money. Internationalisation is about culture.

When Jean Monnet said that, if he had founded the European Union again, he would have based it on culture not trade – he was saying something very important about the differences between globalisation (or mondalisation as the French coined the phrase) and Liberal internationalism.

Where Liberals have been too forgiving to the EU, it is because they have muddled the two. Just because an institution claims to be international does not make it Liberal.

It seems to me that Liberals bring an insight to the debate about the difference between nationalism and self-determination.

The saving grace of the EU is that it draws the claws of the nationalists – who represent the opposite to Liberals in any ideology. It blurs national boundaries. It means that Scots or Catalans can determine their own affairs if they want to, within the overarching structures of the EU.

It means we can be diverse and look after our own affairs, if we want to, without being either absolutely in or absolutely out of the nation. That is the basis of the Anglo-Irish agreement too.

My great-aunt used to say that the only nationalism which English Liberals were prepared to smile upon was Irish nationalism, and there is some truth in this. But it means that, when I am in favour of Scottish independence, or even Yorkshire independence, within an international framework – as I am – it is because I am a Liberal not a nationalist.

And because I believe that small nations are a fundamentally peaceful and humane architecture for the world.

The great Liberal John Maynard Keynes set out the difference pretty clearly, it seems to me:

“I sympathise with those who would minimise, rather than those who would maximize economic entanglements among nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel — these are things that of their nature should be international. But let goods be homespun wherever it is reasonable and conveniently possible, and above all, let finance be primarily national.”

Except for what he says about money, this is absolutely right. Money has to be all three.

That is the Liberal answer to globalisation, it seems to me. Ideas, knowledge, culture has to be the basis for internationalism. This isn’t a basis for outlawing international trade – quite the reverse – but it is a basis for relying on it a bit less.

Published on June 10, 2013 03:27

June 9, 2013

All regimes try to develop poor people's parks

The stand-off in Ankara about the future of a public park that is about to be handed over to developers has been treated by the media for what it says about the Turkish government and its relations with ordinary people. What the story really demonstrates is the vital importance of green spaces in people's lives.

We are extraordinarily lucky in British cities with open green space, though the environments the poor have to live in are often unremittingly brutal - especially in the big cities and thanks to the architectural fantasies of the 1960s and 70s, a blot on the reputation of municipal housing.

What we forget is that, as in Ankara, it all has to be fought for. I have commons all around where I live in South London, and every one of them has required campaigning defence and sometimes direct action - from tearing down the fences enclosing Sydenham Common in the 17th century to tearing down the fences enclosing Plumstead Common in the 19th century.

My own nearest park is Norwood Grove, which twice had to be defended from developers - in 1913 and 1924 - until it was bought by public subscription. It is a major civilising influence on the area (though I expect some economists would complain that building on it would create economic growth).

So the defence of a park in Ankara may not actually mean that the regime is particularly brutal (though the police clearly are). All regimes try to develop the parks used by poor people. What it does show is that Turkey is politically mature enough for people to hang on to their park for dear life.

What worries me is that we haven't learned the latest lessons of green space in UK policy either. We already know from there that mental health problems are enormously higher in high-density concrete estates without grass or trees. But it is now also clear from research that:

71 per cent in one Mind survey reported lower levels of depression after walking in a country park (22 per cent found an equivalent walk through a shopping centre made them more depressed).24 per cent fewer sick visits among prisoners in Michigan in cells that overlooked farmland and trees.Shorter hospital stays, fewer painkillers, less medication for Pennsylvania patients when they had views of trees.

These are important findings, and the Netherlands now has 600 ‘care farms’ in the countryside to tackle depression, integrated into their health service (we have 42). They imply that human beings have a basic need for green, natural space and trees.

One study in Seattle even found that turnover in shops were higher when there were trees in the shopping street, so there are direct economic links as well.

All this also implies that the green movement, in the UK at least, is partly responsible for the rise in mental illness. Green campaigners have been at the forefront of calling for high density cities, and high density flats, over the past two decades, and high densities necessarily means less greenery.

The hideous results – at least for those who have to live in them – are all too obvious, just as they were two generations ago when environmentalists and architects last ganged up to raise urban densities. Then as now, it was the poor that suffered – without any obvious reduction in traffic either.

But the third implication is more urgent. There is a political opportunity here, because there is – hidden in this research – a note of hope. We can have an impact on the epidemic of depression that is undermining our society but not if we reserve the dullest, concrete environments from the people they are most likely to damage.

We are extraordinarily lucky in British cities with open green space, though the environments the poor have to live in are often unremittingly brutal - especially in the big cities and thanks to the architectural fantasies of the 1960s and 70s, a blot on the reputation of municipal housing.

What we forget is that, as in Ankara, it all has to be fought for. I have commons all around where I live in South London, and every one of them has required campaigning defence and sometimes direct action - from tearing down the fences enclosing Sydenham Common in the 17th century to tearing down the fences enclosing Plumstead Common in the 19th century.

My own nearest park is Norwood Grove, which twice had to be defended from developers - in 1913 and 1924 - until it was bought by public subscription. It is a major civilising influence on the area (though I expect some economists would complain that building on it would create economic growth).

So the defence of a park in Ankara may not actually mean that the regime is particularly brutal (though the police clearly are). All regimes try to develop the parks used by poor people. What it does show is that Turkey is politically mature enough for people to hang on to their park for dear life.

What worries me is that we haven't learned the latest lessons of green space in UK policy either. We already know from there that mental health problems are enormously higher in high-density concrete estates without grass or trees. But it is now also clear from research that:

71 per cent in one Mind survey reported lower levels of depression after walking in a country park (22 per cent found an equivalent walk through a shopping centre made them more depressed).24 per cent fewer sick visits among prisoners in Michigan in cells that overlooked farmland and trees.Shorter hospital stays, fewer painkillers, less medication for Pennsylvania patients when they had views of trees.

These are important findings, and the Netherlands now has 600 ‘care farms’ in the countryside to tackle depression, integrated into their health service (we have 42). They imply that human beings have a basic need for green, natural space and trees.

One study in Seattle even found that turnover in shops were higher when there were trees in the shopping street, so there are direct economic links as well.

All this also implies that the green movement, in the UK at least, is partly responsible for the rise in mental illness. Green campaigners have been at the forefront of calling for high density cities, and high density flats, over the past two decades, and high densities necessarily means less greenery.

The hideous results – at least for those who have to live in them – are all too obvious, just as they were two generations ago when environmentalists and architects last ganged up to raise urban densities. Then as now, it was the poor that suffered – without any obvious reduction in traffic either.

But the third implication is more urgent. There is a political opportunity here, because there is – hidden in this research – a note of hope. We can have an impact on the epidemic of depression that is undermining our society but not if we reserve the dullest, concrete environments from the people they are most likely to damage.

Published on June 09, 2013 04:19

June 8, 2013

Would Heathrow ever stop expanding?

It really is extraordinary that more homes, families and villages are being blighted by yet another plan for a third runway from Heathrow's stubborn bosses, to boost their shopping centre with airport attached.

It really is extraordinary that more homes, families and villages are being blighted by yet another plan for a third runway from Heathrow's stubborn bosses, to boost their shopping centre with airport attached.No doubt it will be accompanied by another of those dubious economic studies which add up all the potential benefits of more flights to China, but don't subtract the costs of all he disbenefits of the extra flights, from noise and carbon emissions, and to health.

The future of Heathrow currently divides the Conservative Party, but there is at heart a more fundamental argument about whether we really make progress by increasing the number of economic exchanges in the economy - the meaning of 'growth' - or whether somebody has to exercise some kind of judgement about what is good 'growth' and what is simply destructive.

Sometimes, you just have to subtract - there are disbenefits. The apotheosis of growth over everything that can't be put into a cost-benefit calculation is, in the end, a corrosion of the language. If we pedal this kind of idea, one day we may be unable to express the reason for our unease as they chop down the forests, demolish the parks and villages, in the name of growth. We will only be able to look at a forest and see the potential paper - just as airport operators can only look at a village and see a potential runway.

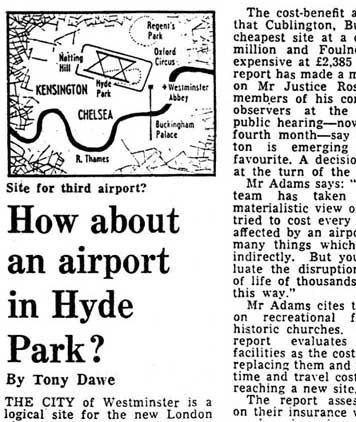

All this reminded me of the crazy story of the biggest cost-benefit analysis ever undertaken, to choose the site for a Third London Airport in 1969.

The government had rejected the preferred site at Stansted in Essex, and for the next two and a half years the commission chaired by the senior judge, Mr Justice Roskill, combed the evidence. To make sure there was a choice of sites, the think-tank the Town and Country Planning Association put in their own planning application to build an airport at Foulness, on marshland off the Essex coast much-frequented by Brent Geese - an early version of Boris Airport.

The Roskill Commission was determined to work out the answer mathematically. They would do a cost benefit analysis on all the possible sites - the biggest analysis of its kind ever carried out. They would put a value on the noise of aircraft, the disruption of building work, the delay of flights, the extra traffic and they would calculate the answer.

For the Roskill Commission, there was going to be no value judgement at all. The figures would speak for themselves. And there was the mistake.

To avoid any chance of judgement and to keep the process completely ‘scientific', the measurements were put together in 25 separate calculations. They were only added up right at the end of the process. And to the horror of some of the members of the commission, when the final addition was made, the answer was wrong.

The site they felt was best - Foulness - was going to be £100 million more expensive in cost benefit terms than the small village of Cublington. After 246 witnesses, 3,850 documents, seven technical annexes and 10 million spoken words, some of the planners on the commission felt cheated.

In public, they stayed loyal to Roskill. The commission was excellent, said Britain's most famous planner Colin Buchanan - a member of it – “it just got the small matter of the site wrong".

The team had managed to measure the exact cost of having too much aircraft noise by looking at the effect noise tended to have on house prices. But when it came to measuring the value of a Norman church at Stewkley, which would have to be demolished to make way for the runway, things got more confused.

How could you possibly put a money price on that? One joker on the team suggested they find out its fire insurance value. Everyone laughed, but the story got out and reached the press. Doing it like that would measure the value of the church at just £51,000.

A fierce political debate erupted. Commission members were accused of being 'philistines'. John Adams, from the University College geography department, drew up an alternative plan. Using similar cost-benefit methods, he showed that the cheapest option would be to build the airport in Hyde Park – but that Westminster Abbey would have to be demolished.

The satire didn’t work: the Sunday Times published a letter from a retired air vice marshal congratulating him for recommending Hyde Park for an airport, and pointing out that he had proposed exactly the same thing in 1946.

And there is the point. If you believe you can really sum everything up in terms of price, you have gone beyond satire.

Published on June 08, 2013 02:04

June 7, 2013

Spirit of '40 not '45

It seems likely that the Labour Party is shifting its position and will adopt the budgets of the coalition. As a result there has been a flurry of debate - well, not quite that - about the funding of public services and the history of the Welfare State since Beveridge. The BBC's Nick Robinson was wheeled out to peer back into the past.

It seems likely that the Labour Party is shifting its position and will adopt the budgets of the coalition. As a result there has been a flurry of debate - well, not quite that - about the funding of public services and the history of the Welfare State since Beveridge. The BBC's Nick Robinson was wheeled out to peer back into the past.Needless to say, this has caused disaffection on the left, and there is talk of yet another new party emerging, thanks to the inspiration from Ken Loach's passionate film Spirit of '45.

Now, I've blogged about this before, after I appeared on Start the Week with Ken Loach, partly to talk about my new book Broke. He shook his head vigorously at me while I spoke, so I suppose it is fair to say that we don't agree.

I think the Attlee government founded some of these institutions that Loach wants to revive complete with the seeds of their own destruction inside them - over-centralised and dangerously over-professionalised. As a result, the institutions have become sclerotic and ineffective, and increasingly expensive. It meant that Beveridge's Five Giants were only temporarily slayed, and come back to life again every generation to be slayed all over again.

So, while I long for the boldness of that government - I think it is time to start looking forward, not endlessly harping back to what we have lost. We can imagine what kind of institutions might work, and it is time to start making them happen.

So, no, I won't be joining a new political movement based on nostalgia for 1945. But what I wanted to say here is that it anyway misses the point.

The real founding moment of the modern British state wasn't 1945 but 1940. That explains our national obsession with the Second World War and the Blitz, but - unlike 1945 - the Spirit of '40 needs a bit more unpacking.

It wasn't just the relief people felt then about 'standing alone', without the complications of allies across the Channel, though there was an element of that. It was the extraordinary sense of national mission and cohesion that had begun to take hold during the Battle of Britain, so different from the divided nation that had gone to war so reluctantly. Even by 1942, people were looking back to that summer of 1940 where everything seemed to be coming together.

Those are all well-known. But the real reason why 1940 remains important in the national psyche has been half forgotten. It was the sense that innovative, effective people could abandon long-establish and stultifying procedures and make things happen. It was the moment when the Old Guard, the appeasers and those who had muddled through the Great Depression, had been swept aside by people who could take events by the scruff of the neck.

In short, it was the moment when the forces of conservatism were pushed out in a moment of supreme crisis.

It might not have happened. Neville Chamberlain would have survived the critical debate on the Norwegian campaign in the House of Commons if the mood had not been changed by the arrival of Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, the hero of Zeebrugge, in the full uniform of an Admiral of the Fleet, who laid into the government from the Conservative benches.

The result was that Chamberlain resigned, Churchill took over and the rest - as they say - was history.

In comparison to this symbolic moment of liberation, the Spirit of '45 was the apotheosis of the professional classes and the Man from Whitehall. It is the Spirit of '40 that still animates.

Published on June 07, 2013 02:29

June 6, 2013

Why centralised procurement is so wildly expensive

At the end of April, I chaired the Public Services Show at the Business Design Centre, and found myself introducing the government's new Chief Operating Officer, Stephen Kelly.

At the end of April, I chaired the Public Services Show at the Business Design Centre, and found myself introducing the government's new Chief Operating Officer, Stephen Kelly.This was a little unnerving because I don't really understand what a COO does in government, and his hand-shake was worryingly mid-Atlantic. But he told the story about his government computer taking seven minutes to turn on - aware that Tesco's computers turn on within seconds and cost a fraction of the vast sums the government is spending.

It was a phenomenon I had noticed when I had a government laptop during the Barriers to Choice Review, and it is certainly strange.

Kelly has now told the story again, pointing out that he spends three days a year just waiting for his computer. It is a telling story and it seems to be assumed in government that this is an argument for centralised procurement. I'm not sure it is.

So pop back two decades with me for a moment, to a wintry evening at the end of 1993, when Al Gore was Vice-president, when a group of radical efficiency types went to see him and persuaded him to launch what became the National Performance Review.

Among those there was the pioneer of entrepreneurial local government Ted Gaebler, co-author of the influential book Reinventing Government. Another was Bob Stone.

Stone had been the Pentagon’s deputy assistant secretary for defence for installations, working out that about a third of the entire defence budget was wasted because of bad regulations, probably amounting to $100bn a year. He experimented by cutting the regulation book for forces housing from 800 pages to 40.

One commander asked permission to let craftsmen decide for themselves which spray paint cans could be thrown away, rather than having each one certified by the base chemist. It was Stone who wrote the original principles that would dominate the National Performance Review.

What was fascinating about the Review was that it was overwhelmingly local. It encouraged people on the frontline to find savings, rather than simply imposing spending rules on them - and it made a great deal of what they found.

Stone’s experience at the Pentagon coincided with the revelations of the cost of simple items when it went through armed forces bureaucracy. The $7,622 coffee percolator bought by the air force was the most spectacular, but the one that really caught the public imagination was the $436 hammer bought for the navy, or – as the Pentagon called it – a ‘uni-directional impact generator’.

One of the first schemes the Review launched was an annual Hammer Award for public sector employees who had made huge efforts to work more effectively. We should do something similar here.

This is what the news report on Kelly said:

"He highlighted the bill for a PC power cable which costs £8 wholesale, was being sold on Amazon for £20 but for which the Cabinet Office was charged £57 by a supplier."

I'm sure that is the tip of the iceberg. There will be some of our very own uni-directional impact generators out there.

But the other thing I learned watching procurement happen at close quarters at the Cabinet Office was that, when once you might get a bit of printing done cheaply and quickly, it now took a huge process and the quotations through the formal process were astronomical.

So despite what Philip Green might say, this is not about scale of procurement. Things work best and cheapest, in my experience, when they are sourced immediately and informally. There will be exceptions to this rule when beating a supplier more egregiously over the head will provide more savings, as Tesco might do. But this is not a universal law.

Quite the reverse, in fact. In most cases, big procurement is more expensive.

Not just because suppliers get away with it or because the lumbering monster that is government procurement often makes a hearty meal of its own tail without realising it. But because the best deals often come from small companies with lower overheads, and big procurement systems - despite the rhetoric - find them extraordinarily hard to deal with.

The result is fewer, bigger companies, more semi-monopolies, and that inevitably means higher prices.

More about this, and about the Hammer Award and Gore's Performance Review, in my book The Human Element.

Published on June 06, 2013 04:14

June 5, 2013

Britons may be slaves after all

It is always a little nerve-wracking when someone whose writing, and whose point of view, you admire enormously takes it upon themselves to review your book.

It is always a little nerve-wracking when someone whose writing, and whose point of view, you admire enormously takes it upon themselves to review your book.Bryan Appleyard's review of my book Broke: Who Killed the Middle Classes is in the New Statesman this week, but isn't online, so I can't link to it. But to my intense relief, it is a generous, thoughtful article, comparing it to another new book called When the Money Runs Out (Stephen King) - and he has not only read the book (a rarity among reviewers) but believes it is "convincing" and "persuasive", and "with some startling asides".

He also doesn't try to belittle the difficulties the middle classes have been having (like the Conservative reviewers have done). Nor does he feel that somehow anyone writing about the middle classes must have it in for the working classes (like the left reviewers have done). In fact, he takes the problem seriously and - better than that - puts it into context.

This is how he concludes:

"There are many more ideas but the attempt to find a story to justify the sacrifices necessary for recovery is the foundation of them all. It is this that joins these two books. Boyle is attempting first to evoke and then to restructure the old story of the busy, sane, thrifty and inventive middle classes in the melancholy pools of the 21st century; King is attempting to wean us off the tales - or fantasies - of inevitable and unending growth. Neither is certain of success, because the hard truth may be that the crash marked the beginning of the end of the story of western success. We may never look with satisfaction in the mirror of money again."

I believe this hits the nail squarely on the head. The real issue is much bigger than whether the middle classes can recover. It is whether the vast majority of the population can claw back some kind of economic resilience at all - or whether the game is now up.

Except for the handful of those at the top of society - actually less than one per cent - then it seems to me that the rules have changed completely. They have changed so slowly that politics has not shifted to take account of it, and - unless mainstream politics can grasp what is going on - then we will be unequipped to avoid the equivalent of economic slavery in the medium term, the very opposite of the property-owning democracy that the current generation was led to expect.

We have none of the concepts and few of the institutions that we need to avoid this, just a vague idea that somehow the way in which we understand money is faulty and no longer works.

This is a failure of economics of course. But it is also a failure of our politics, because our politicians regard our current difficulties as a bump in the road rather than the foothills of an entirely different landscape.

This sounds depressing, and some of the reviews have emphasised this. But I've tried to write a book which sketches out a roadmap to a different political future, and - more than that - I've tried to write a book which is also fun to read. It might be challenging, but it is also strangely amusing...

Published on June 05, 2013 01:51

June 4, 2013

A staggering political blindness about banks

The really appears to be a blindness among frontline politicians about the banks, even many of the Lib Dem ones - though Vince Cable appears to be pretty clear-sighted about it. If so, he is in a tiny minority.

It isn't that some of them somehow think the banks are effective generators of economic success. Nobody could think that. Or even that the big bankers are right that there is no demand for business lending. Nearly everybody recognises that is nonsense.

No, the big politicians' fantasy is why there is a problem. They maintain themselves in the delusion that somehow this is laziness or greed, just bad behaviour by the banks that can be corrected by a stiff talking-to, or by some lending scheme which allows them to profit from actually doing what they were originally designed to do. It is part of the politicians' more common fantasy that they have the leverage if only they knew how to wield it.

None of this is true. Banks are not lending to small and medium-sized businesses in the UK because they are no longer set up to do so. They have no local infrastructure capable of making decisions, which can over-ride their risk software - which simply tells them 'no'.

But until the frontline politicians can grasp this, nothing can be done. Other countries have small local banks with that capability; we don't - why don't they grasp the disadvantage we have? - and haven't done for more than a generation.

Why was UK industry so pathetically badly invested - and why is it still? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Why do we have to wait for a recovery led by Tesco and their cronies unleashing their war chests, when other countries have entrepreneurs leading the recovery? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Why is the Co-op Bank in trouble after their Britannia Building Society takeover? Because they lack the infrastructure to lend (except on property).

And the latest figures confirm it. Bank lending to business is down, despite the subsidies from the government's Funding for Lending scheme. Lending is up on property (yes, it is the British disease again - when in doubt press the housing bubble button). It is worst with the banks in public ownership, which I suppose demonstrates that the Treasury rates preparation for privatisation higher than playing an effective role in the recovery.

I even heard of a small business on the radio this evening which has been forced to go to online lenders for the money they need to expand (and have accepted a loan at 13 per cent APR).

Why? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Small business lending can't be done by computer. It requires local knowledge. Other countries have that infrastructure. How come we are in the third year of the coalition, and yet there is still little prospect that we are going to organise it for the UK too?

It isn't that some of them somehow think the banks are effective generators of economic success. Nobody could think that. Or even that the big bankers are right that there is no demand for business lending. Nearly everybody recognises that is nonsense.

No, the big politicians' fantasy is why there is a problem. They maintain themselves in the delusion that somehow this is laziness or greed, just bad behaviour by the banks that can be corrected by a stiff talking-to, or by some lending scheme which allows them to profit from actually doing what they were originally designed to do. It is part of the politicians' more common fantasy that they have the leverage if only they knew how to wield it.

None of this is true. Banks are not lending to small and medium-sized businesses in the UK because they are no longer set up to do so. They have no local infrastructure capable of making decisions, which can over-ride their risk software - which simply tells them 'no'.

But until the frontline politicians can grasp this, nothing can be done. Other countries have small local banks with that capability; we don't - why don't they grasp the disadvantage we have? - and haven't done for more than a generation.

Why was UK industry so pathetically badly invested - and why is it still? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Why do we have to wait for a recovery led by Tesco and their cronies unleashing their war chests, when other countries have entrepreneurs leading the recovery? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Why is the Co-op Bank in trouble after their Britannia Building Society takeover? Because they lack the infrastructure to lend (except on property).

And the latest figures confirm it. Bank lending to business is down, despite the subsidies from the government's Funding for Lending scheme. Lending is up on property (yes, it is the British disease again - when in doubt press the housing bubble button). It is worst with the banks in public ownership, which I suppose demonstrates that the Treasury rates preparation for privatisation higher than playing an effective role in the recovery.

I even heard of a small business on the radio this evening which has been forced to go to online lenders for the money they need to expand (and have accepted a loan at 13 per cent APR).

Why? Because the banks lack the infrastructure to lend.

Small business lending can't be done by computer. It requires local knowledge. Other countries have that infrastructure. How come we are in the third year of the coalition, and yet there is still little prospect that we are going to organise it for the UK too?

Published on June 04, 2013 02:07

June 3, 2013

There is a future for GPs, but it's flexible

While I was doing the government's review on Barriers to Choice last year, the most common complaint at round tables was about getting appointments to see GPs.

This was unexpected because the official research for the Department of Health, every year, does not pick this up. Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence - which is important here - suggests that some people, maybe older people in particular, do have difficulties here. I find it quite hard myself sometimes, at least if you wait until you really need it.

So when I woke up a few days ago with another mild chest infection, I thought of this - and found myself planning ahead to book an appointment with my GP, not to tackle the problem now (which isn't really necessary), but in case I need one at the end of the week. Because, if I wait until then, I won't get an appointment.

Imagine that kind of decision - pre-emptive GP appointments - being made and booked all over the country and it begins to become clearer why GPs are being overwhelmed.

The influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley tackled GPs at the end of last week, and absolutely hit the nail on the head about how they need to be reinvented. Doctors who answer the phone in the morning to triage the patients themselves. Special practice nurses to coach the long-term conditions to self-manage, and surgeries linked to classes, drop-in coffee mornings and, he might have added, time banks - like the one at Rushey Green.

It is true that GPs are now under increasing pressure as the the most frontline service of all. It means they now have to be the gatekeepers also, via their surgeries, of the new mutual support infrastructure that can provide people with advice, companionship, expert patient support and the gateway also to social care.

That is not something they can do all by themselves, which means that the old days of sole practice doctors - like the wonderful one who used to treat me when I was a child (Dr Morgan) - are probably now on the way out. But there are ways of doing things differently that will make a difference, if they can get their patients to help - if surgeries become hubs capable of knitting society back together again, relationship by relationship.

And if they can abandon the old rigities that assume that access by patients has to be controlled, and then they must all be offered precisely seven minutes in the consulting room and a new prescription, when many would prefer an occasional email to make sure things are OK - and not all of them will need to be to the doctor.

These kind of rigities are repeated throughout the NHS. Why do patients have to see their consultants every six months, come rain or shine, well or ill? Why can nobody talk to doctors by email? Why do people with chronic conditions need to be maintained in ill-health for the rest of their lives at great expense?

All of which is a way of saying that the resources are there, if we can be more flexible.

This was unexpected because the official research for the Department of Health, every year, does not pick this up. Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence - which is important here - suggests that some people, maybe older people in particular, do have difficulties here. I find it quite hard myself sometimes, at least if you wait until you really need it.

So when I woke up a few days ago with another mild chest infection, I thought of this - and found myself planning ahead to book an appointment with my GP, not to tackle the problem now (which isn't really necessary), but in case I need one at the end of the week. Because, if I wait until then, I won't get an appointment.

Imagine that kind of decision - pre-emptive GP appointments - being made and booked all over the country and it begins to become clearer why GPs are being overwhelmed.

The influential NHS blogger Roy Lilley tackled GPs at the end of last week, and absolutely hit the nail on the head about how they need to be reinvented. Doctors who answer the phone in the morning to triage the patients themselves. Special practice nurses to coach the long-term conditions to self-manage, and surgeries linked to classes, drop-in coffee mornings and, he might have added, time banks - like the one at Rushey Green.

It is true that GPs are now under increasing pressure as the the most frontline service of all. It means they now have to be the gatekeepers also, via their surgeries, of the new mutual support infrastructure that can provide people with advice, companionship, expert patient support and the gateway also to social care.

That is not something they can do all by themselves, which means that the old days of sole practice doctors - like the wonderful one who used to treat me when I was a child (Dr Morgan) - are probably now on the way out. But there are ways of doing things differently that will make a difference, if they can get their patients to help - if surgeries become hubs capable of knitting society back together again, relationship by relationship.

And if they can abandon the old rigities that assume that access by patients has to be controlled, and then they must all be offered precisely seven minutes in the consulting room and a new prescription, when many would prefer an occasional email to make sure things are OK - and not all of them will need to be to the doctor.

These kind of rigities are repeated throughout the NHS. Why do patients have to see their consultants every six months, come rain or shine, well or ill? Why can nobody talk to doctors by email? Why do people with chronic conditions need to be maintained in ill-health for the rest of their lives at great expense?

All of which is a way of saying that the resources are there, if we can be more flexible.

Published on June 03, 2013 03:43

May 31, 2013

The future of public services isn't sharing info - it's upside down

One of the most inspiring visits I made for the government's Barriers to Choice Review last year was to Middlesborough, to meet people involved in the new Local Area Co-ordination scheme there.

Perhaps it isn't the most impressive name to use for something that has turned social care upside down in Western Australia, but it manages to combine higher support from care users and lower costs - which isn't unique, but is a sign that something important is going on.

LAC started in Western Australia in 1988, thanks to the social services director Eddie Bartnik. It is now used to support social care in other Australian states and has been successfully adopted in Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand, Canada and now England, starting in Middlesborough and Derby, as an approach to early intervention and prevention.

LACs are generalists who support practical, creative and informal ways of meeting people’s aspirations and needs, increasing the control and range of choices for individuals, their carers and families. Their activities focus on supporting vulnerable people to build a vision for a good life that is individual to them, and to build the family, relationship and community networks that make it possible.

LAC operates at individual, family and community levels and can help individuals, their carers and families to plan, select and receive a range of support and services to achieve their vision for a good life, enormously increasing the flexibility of services and providing users with much broader choices.

What is fascinating about LAC is that it is absolutely cross-service. The first point of contact is someone who will focus - not on your needs - but on what you want to achieve, what informal support you might need to get there, who they know who might help. Then they will coach you to a position where you are much more active in your own life. Only if that fails, do they fall back on the traditional care support packages.

I was interested then because I had suspected for some time that there is a new kind of profession emerging in public services, which has many of those characteristics - asset-based, as they say in the jargon, cross-departmental, starting from where each individual is in their life at the time.

I mention this because I read a post yesterday from the very energetic thinkers in the iNetwork in the north west about the health and well-being 'timebomb', which also linked me to the ambitious joint statement by almost everyone in the health and social care field about integrated care.

I would disagree with nothing in either of these, but the success of Local Area Co-ordination seems to me to point in a different direction. Not one that is basically about 'joint working', 'sharing information', 'co-ordinated care' or any of those phrases which imply that this is basically an information and co-ordination problem.

I don't believe that a social care system which now sends seven agencies to your front door can survive - and I don't believe it can survive, even if they share information seamlessly between them.

What Eddie Bartnik, and his UK vicar-on-earth Ralph Broad, have developed is the beginnings of a different kind of system altogether, which starts from hopes not needs, and which has a multi-disciplinary, semi-informal human face at the front of it. Local Area Co-ordinators can still fall back on professionals if they need to, but often they don't need to.

The Barriers to Choice Review taught me that that sheer inflexibility of the current system, the multiplicity of agencies, must make way for something much more flexible - and I suspect that means the following:

1. Turning services upside down so that informal solutions and social support is the first resort, not the last.

2. Merging public services together locally, schools, health, social care, housing, and so on.

3. Turning those hubs into catalysts for an enormous increase in local involvement and mutual support (co-production).

4. Concentrating resources at the intractable problems, the small number of people and families who both slip through the cracks of the current system and involve most of the costs.

Perhaps it isn't the most impressive name to use for something that has turned social care upside down in Western Australia, but it manages to combine higher support from care users and lower costs - which isn't unique, but is a sign that something important is going on.

LAC started in Western Australia in 1988, thanks to the social services director Eddie Bartnik. It is now used to support social care in other Australian states and has been successfully adopted in Scotland, Ireland, New Zealand, Canada and now England, starting in Middlesborough and Derby, as an approach to early intervention and prevention.

LACs are generalists who support practical, creative and informal ways of meeting people’s aspirations and needs, increasing the control and range of choices for individuals, their carers and families. Their activities focus on supporting vulnerable people to build a vision for a good life that is individual to them, and to build the family, relationship and community networks that make it possible.

LAC operates at individual, family and community levels and can help individuals, their carers and families to plan, select and receive a range of support and services to achieve their vision for a good life, enormously increasing the flexibility of services and providing users with much broader choices.

What is fascinating about LAC is that it is absolutely cross-service. The first point of contact is someone who will focus - not on your needs - but on what you want to achieve, what informal support you might need to get there, who they know who might help. Then they will coach you to a position where you are much more active in your own life. Only if that fails, do they fall back on the traditional care support packages.

I was interested then because I had suspected for some time that there is a new kind of profession emerging in public services, which has many of those characteristics - asset-based, as they say in the jargon, cross-departmental, starting from where each individual is in their life at the time.

I mention this because I read a post yesterday from the very energetic thinkers in the iNetwork in the north west about the health and well-being 'timebomb', which also linked me to the ambitious joint statement by almost everyone in the health and social care field about integrated care.

I would disagree with nothing in either of these, but the success of Local Area Co-ordination seems to me to point in a different direction. Not one that is basically about 'joint working', 'sharing information', 'co-ordinated care' or any of those phrases which imply that this is basically an information and co-ordination problem.

I don't believe that a social care system which now sends seven agencies to your front door can survive - and I don't believe it can survive, even if they share information seamlessly between them.

What Eddie Bartnik, and his UK vicar-on-earth Ralph Broad, have developed is the beginnings of a different kind of system altogether, which starts from hopes not needs, and which has a multi-disciplinary, semi-informal human face at the front of it. Local Area Co-ordinators can still fall back on professionals if they need to, but often they don't need to.

The Barriers to Choice Review taught me that that sheer inflexibility of the current system, the multiplicity of agencies, must make way for something much more flexible - and I suspect that means the following:

1. Turning services upside down so that informal solutions and social support is the first resort, not the last.

2. Merging public services together locally, schools, health, social care, housing, and so on.

3. Turning those hubs into catalysts for an enormous increase in local involvement and mutual support (co-production).

4. Concentrating resources at the intractable problems, the small number of people and families who both slip through the cracks of the current system and involve most of the costs.

Published on May 31, 2013 02:34

May 30, 2013

A new kind of liberalism has to emerge

I listened to Bea Campbell and Laurie Penny on the Today programme with a sense of nostalgia. Of course, I felt, we all used to be like that – we all used to enjoy those endless, repeated, circular arguments about the nature of men and women.

This particular argument will have been recognised by all of us who remember the 1970s and the brand of feminism that emerged from there – it is the central tenet of small-L modern liberalism: that anybody can be anything. That all human difference, and gender differences, are down to cultural stereotyping.

It was a useful thing to think, and it drove the kind of tolerant society we have now (where it remains tolerant), but it overstated the case.

We should not be imprisoned by our differences, but of course there are variations between the genetic make-up and pre-dispositions of men and women, and many sub-classes of those too. We refuse to be categorised – that is the core belief of liberalism – but the categories are there, and you can see them under a microscope.

I am a product of my own time, as well as everything else, so I accept the premise. I believe that individual possibilities are unlimited.

But there is a hidden danger here, and it is a danger for liberalism too. If we recognise no limits, no communities, no ideals, no institutions, no relationships, no belief systems, no common moralities, then we fling ourselves into a whole new kind of tyranny – and we will be undefended against the intolerant forces of fundamentalism battering on the gate.

Liberalism has been a liberating, but – let’s face it – also a corrosive creed. It allied itself with the power of money in the nineteenth century, aware that money would corrode privilege and power wherever it was. The power of church and aristocracy crumbled and fell before it, seeking out American heiresses to prop it up.

The danger for liberalism is that the power of measuring everything in terms of money just carried on corroding. So does the power of individual self-determination.

The truth is that human civilisation and well-being depends on us setting limits to ourselves - in relationships, in behaviour, even just on the London underground. When we limit ourselves to seasonal fruit and veg, for example - rather than satisfying our craving for strawberries which have to be flown in for Christmas - we lead a better life, paradoxically.

Because, in the end, we are moral beings and our shared morality is stronger – or it ought to be – than any of the forces unleashed by the great wave of liberalism over the past two centuries, money and self-determination.

Because, in the end, the argument put forward by Bea Campbell has been overtaken by science and genetics.

This is a crisis for cultural liberalism, and it needs to be rescued by political Liberalism. We are not in an entirely relativist world, after all. There are many ways of looking at morality, but not all of them are valid. We need to be able to defend the tolerant society we have created – and on the grounds put forward by Karl Popper when it was last under attack: because the open society “sets free the critical powers of man” (he meant also the critical powers of women!).

For me, this is a new kind of liberalism, beyond the kind of lazy relativism that we have been living with, and because it emphasises what we share – our humanity. We are not just isolated, self-determining individuals, who can’t communicate with each other without the support of the institutions of political correctness.

We are human beings, with a shared genetic heritage, diverse enough to be ourselves, but with enough between us to learn together, to love and to defend our tolerant institutions.

And if all we can do, when that tolerance is threatened by machete-wielding terrorists is to interview spokespeople for the security industry like John Reid, or with breathless horror devote our front pages to the terrorists' demands – with hardly a word about what we are defending – well then, the achievements of liberalism will be seriously under threat.

Amazing, Bea Campbell and feminism to John Reid and machetes in a few deft sentences...

This particular argument will have been recognised by all of us who remember the 1970s and the brand of feminism that emerged from there – it is the central tenet of small-L modern liberalism: that anybody can be anything. That all human difference, and gender differences, are down to cultural stereotyping.

It was a useful thing to think, and it drove the kind of tolerant society we have now (where it remains tolerant), but it overstated the case.

We should not be imprisoned by our differences, but of course there are variations between the genetic make-up and pre-dispositions of men and women, and many sub-classes of those too. We refuse to be categorised – that is the core belief of liberalism – but the categories are there, and you can see them under a microscope.

I am a product of my own time, as well as everything else, so I accept the premise. I believe that individual possibilities are unlimited.

But there is a hidden danger here, and it is a danger for liberalism too. If we recognise no limits, no communities, no ideals, no institutions, no relationships, no belief systems, no common moralities, then we fling ourselves into a whole new kind of tyranny – and we will be undefended against the intolerant forces of fundamentalism battering on the gate.

Liberalism has been a liberating, but – let’s face it – also a corrosive creed. It allied itself with the power of money in the nineteenth century, aware that money would corrode privilege and power wherever it was. The power of church and aristocracy crumbled and fell before it, seeking out American heiresses to prop it up.

The danger for liberalism is that the power of measuring everything in terms of money just carried on corroding. So does the power of individual self-determination.

The truth is that human civilisation and well-being depends on us setting limits to ourselves - in relationships, in behaviour, even just on the London underground. When we limit ourselves to seasonal fruit and veg, for example - rather than satisfying our craving for strawberries which have to be flown in for Christmas - we lead a better life, paradoxically.

Because, in the end, we are moral beings and our shared morality is stronger – or it ought to be – than any of the forces unleashed by the great wave of liberalism over the past two centuries, money and self-determination.

Because, in the end, the argument put forward by Bea Campbell has been overtaken by science and genetics.

This is a crisis for cultural liberalism, and it needs to be rescued by political Liberalism. We are not in an entirely relativist world, after all. There are many ways of looking at morality, but not all of them are valid. We need to be able to defend the tolerant society we have created – and on the grounds put forward by Karl Popper when it was last under attack: because the open society “sets free the critical powers of man” (he meant also the critical powers of women!).

For me, this is a new kind of liberalism, beyond the kind of lazy relativism that we have been living with, and because it emphasises what we share – our humanity. We are not just isolated, self-determining individuals, who can’t communicate with each other without the support of the institutions of political correctness.

We are human beings, with a shared genetic heritage, diverse enough to be ourselves, but with enough between us to learn together, to love and to defend our tolerant institutions.

And if all we can do, when that tolerance is threatened by machete-wielding terrorists is to interview spokespeople for the security industry like John Reid, or with breathless horror devote our front pages to the terrorists' demands – with hardly a word about what we are defending – well then, the achievements of liberalism will be seriously under threat.

Amazing, Bea Campbell and feminism to John Reid and machetes in a few deft sentences...

Published on May 30, 2013 07:50

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.